WOMEN IN CHINA

Women in China have traditionally been taught to be quiet and discreet. Openly speaking one's mind has traditionally been frowned upon. One 33-year-old man told AP, he liked his wife because she "is simple and tender and never asks too much." “Tradition has come back strongly, but it’s not always a good thing,”a successful Chinese businesswoman told the New York Times. “With Chinese men, there is a line you cannot cross. They have “face” that you have to respect. Anyway, most of them don’t find me feminine. They like young girls. They think a woman is beautiful when she’s “sweet.”

Chinese men reportedly like demure "feminine" women and feel threatened by more aggressive, educated modern women. Beauty is probably less prized in China than it is in other cultures. A good bride is considered to be a woman who can "cook, look after her husband and give him sons" and be willing to "eat bitterness." Shanghai women are known as demanding wives and driven consumers. Many regard them as trouble. Sichuan women are regarded as the most beautiful in China. They are also thought of as temperamental and tempestuous.

Professor Fu Tan-ming, a social behavioural analyst based in Beijing, told the Malaysian newspaper The Star that Chinese women with a history of suffering are more resilient than the men. “They have a stubborn streak in them that propels them forward,” he said. “They would not think twice about packing up their bags to begin life anew thousands of miles away from home. Why? It’s because they know they can survive.” [Source: Seah Chiang Nee, The Star, May 30, 2009]

Percentage of the population that is female: 48.7 percent (compared to 50.5 percent in the United States, 53 percent in Estonia and 37.1 percent in Bahrain) [Source: World Bank data.worldbank.org ]

Gender Statistics:

Labor Force Participation by persons aged 15 to 24 by sex: 59.6 percent for men and 55.1 percent for women, 2010;

Labor Force Participation by persons over 15 by sex: for 78.2 percent men and 63.7 percent for women, 2010;

Enrollment in secondary school: 94.2 percent for men and 95.9 percent for women, 2013;

Under Five mortality rates (deaths per 100,000 births): 13.3 for men and 11.7 for women, 2013;

Proportion of seats held by women in parliament: 25 percent.

Adolescent birth rate (births per 1,000 females, aged 15-19): 9.2, 2015. This was down from 11.2 in 2014.

Average number of hours spent on domestic chores: 1.42 hours for men for 3.68 hours women, 2018

[Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division, genderstats.un.org ]

China ranked 107th out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum's 2021 Global Gender Gap Report. It did better than Japan, ranked 120th and a little worse than South Korea, ranked 102nd. China ranked 118th out of 144 countries in the World Economic Forum's 2017 Global Gender Gap Report.

See Separate Articles: WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; TIGER MOTHER AMY CHUA factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com CONCUBINES AND MISTRESSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com PROBLEMS FACED BY WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com SUCCESSFUL WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA: DONG MINGZHU AND SHENGNU LADIES factsanddetails.com ; MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN TRAFFICKING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Women in Modern China “The Good Women of China: Hidden Voices” by Xinran, Cindy Kay, et al Amazon.com; “Women, Gender, and Sexuality in China” by Ping Yao Amazon.com; “Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love” by Xinran Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Leftover in China: The Women Shaping the World's Next Superpower” by Roseann Lake Amazon.com; “Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China” by Leta Hong Fincher and Paul French Amazon.com; “Out to Work: Migration, Gender, and the Changing Lives of Rural Women in Contemporary China” by Arianne M. Gaetano Amazon.com; “Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China” by Leslie T. Chang, Susan Ericksen, et al. Amazon.com; “The Missing Girls and Women of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: A Sociological Study of Infanticide, Forced Prostitution, Political Imprisonment, "Ghost Brides," Runaways and Thrownaways, 1900-2000s” by Hua-Lun Huang Amazon.com; “Lost and Found: The "Missing Girls" in Rural China” by John James Kennedy, Yaojiang Shi Amazon.com Women in Pre-Revolutionary China “Instructions for Chinese Women and Girls” by Zhao Ban, Esther E Jerman, Amazon.com ; “The Chinese Book of Etiquette and Conduct for Women and Girls, Entitled, Instruction for Chinese Women and Girls” (1900) by Chao Pan Amazon.com; “The Mother (1931) by Pearl S. Buck Amazon.com; Women in Revolutionary China “Women and China's Revolutions” by Gail Hershatter Amazon.com; “To the Storm: the Odyssey of a Revolutionary Chinese Woman” by Yue Daiyun and Carolyn Wakeman Amazon.com; “A Daughter of Han: The Autobiography of a Chinese Working Woman” by Ida Pruitt (1945) Amazon.com

Book: Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, a four-volume collection edited by Lily Xiao Hong Lee, the late Agnieszka Stefanowska, Sue Wiles, and a host of special subject editors and contributors, M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2014]

Sex Ratio in China

China had one of the greatest gender disparities among newborns of any country in the world, all the more alarming because China is such a populous nation. In 2005, 118 boys were born for every 100 girls, up from 110 boys per 100 girls in 2000 and 112 in 1990. One Chinese expert told the Times of London in the late 2000s the rate seemed to have peaked at 120.4 at the end of 2006. The sex ratio in China is better than it used to be but still favors males. Worldwide, 103 to 107 boys are born for every 100 girls.

China had one of the greatest gender disparities among newborns of any country in the world, all the more alarming because China is such a populous nation. In 2005, 118 boys were born for every 100 girls, up from 110 boys per 100 girls in 2000 and 112 in 1990. One Chinese expert told the Times of London in the late 2000s the rate seemed to have peaked at 120.4 at the end of 2006. The sex ratio in China is better than it used to be but still favors males. Worldwide, 103 to 107 boys are born for every 100 girls.

According to the 2020 census in China, the male population of mainland China in 2020 was 723.3 million, accounting for 51.24 percent of the total. The the female population was 688.44 million, 48.76 percent. The sex ratio of the population was 105 men for every 100 women, slightly lower than that of 2010. The sex ratio at birth was 111.3 male babies for every 100 female babies, a decrease of 6.8 from 2010. [Source: Ryan Woo and Raju Gopalakrishnan, Reuters, May 11, 2021]

Sex ratio:

at birth: 1.11 male(s)/female

0-14 years: 1.16 male(s)/female

15-24 years: 1.17 male(s)/female

25-54 years: 1.05 male(s)/female

55-64 years: 1.02 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.9 male(s)/female

total population: 1.06 male(s)/female (2020 est.)

[Source: CIA World Factbook, 2021]

See Separate Articles: SEX RATIO, PREFERENCE FOR BOYS AND MISSING GIRLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULATION GROWTH IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES IN CHINA: factsanddetails.com ; BIRTH CONTROL IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SURROGATE BIRTHS, FROZEN EGGS AND IN-VITRO TREATMENTS AMONG CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; ABORTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BRIDE SHORTAGE, UNMARRIED MEN AND FOREIGN WOMEN FOR SALE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com

Status of Women in China

Women have played key roles in Chinese history. Several women served as empress. The Dowager Empress Jixi was one of the world’s powerful and longest ruling leaders. Empress Wu Ze Tian, a 7th century ruler, changed the name of the Tang dynasty to Zhou, had her own harem of men. Tang Dynasty women held high government offices, played polo with men and wore men’s clothes. Mao’s wife Jiang Qing was the leader of the Gang of Four and regarded by some as the mastermind behind the Cultural Revolution. See Separate Article GREAT WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com

The status of a Chinese woman is often determined by her success at being a wife and a mother, often measured by performance of her children in school. Many Chinese women seem shy, submissive, demure, innocent and sweet when they are young, and become rough, loud, and pushy after they get married.

Women have traditionally been expected to be loyal, faithful and modestly dressed. Many women regard themselves as soft on the outside but strong in their hearts. Some have said the traditional identify of a Chinese woman is defined in terms of two female archetypes — the “loving kind angel” and the “working warrior” — which are almost diametrically opposed and difficult to reconcile. In the cities woman often affect a certain amount of physical helplessness.

Things have changed a lot in recent years especially as women have left the villages and gone to the cities to work. But some have not changed so much. Leta Hong Fincher wrote in her book “Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China”: “In today’s China, when some parents prefer to give money to their nephew rather than to their own daughter to buy a home, they are reverting back to the practice from the Ming dynasty, when, in the absence of sons, daughters had less of a claim to property than nephews.”

See Separate Articles WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com

Low Status of Women in China

In many parts of China women do not have the legal right to own land and are generally regarded as weaker, dumber and inferior to men. A Hong Kong feminist told AFP, "When we are born we have the status of scum. In villages, women have no right to talk about their basic rights. All we need to learn is how to put up with men." A Chinese village woman told the Washington Post, “Women are inferior from the time they’re born. You give birth to a girl people say you have a “potatou”, a worthless servant girl. When it’s a boy, they say you have a “dapangxiaozi”, a big fat boy.”

Traditionally, when women got married they were no longer considered part of the family in which they were born. Instead they became the possession of their husband’s family. Maggie Far of the Los Angeles Times wrote that many rural Chinese compare raising a daughter to "fattening a hog for someone else's banquet" and spending money on them as "scattering seeds to the wind."

In the old days it wasn’t uncommon for village women to be kidnapped and made into concubines for warlords or wealthy people and never be heard from again. Up until the end of the 19th century, Chinese women were often called Daughter No. 1 or Daughter No. 2, etc. until the became Wife No 1. or Wife No. 2. For most of history, Chinese women viewed themselves in terms of the “three obediences” — servants to their father's first, then their husband's and finally their sons.

In villages women often do most of the work, and even then are ordered around by men and are only allowed to eat after the men have finished. Many such women say they don’t miss their husbands when they are away or even when they are dead and those that do miss their husbands only say they do because they sometimes help with the work.

In some cases young girls are still virtually sold into their marriages, and are treated like servants in their households, pushed around by their husband and in laws, especially their mother in law. The tension between the wife and mother-in-law stems from the fact that mothers-in-law expect their daughters-in-law to be servants just as they were to their husband's mothers-in-law.

In the old days, women accused of adultery were sometimes subjected to horrible punishments such as "peeling the skin off the bones" until the victim died. Widows showed their loyalty by not remarrying. Many had no means of taking care of themselves and died from hunger. One Sung dynasty Confucian philosopher wrote, "It is trifling when a widow starved to death. But it is a very serious matter when she loses her chastity.”

See Suicide, Poor and Social Problems

Traditional Gender Roles in China

Household division of labor in China is based primarily on gender. Women have traditionally dominated the domestic sector, managing the household and looking after members of the family, while men traditionally took care of affairs outside the home. Regarding decisionmaking in the household, the husband has traditionally had absolute power but women sometimes controlled the household finances. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”, published in 1894: “Chinese ideas of etiquette require that men and women should keep aloof from each other, even if they happen to be members of the same family.... Yet Chinese men and women will speak to each other, not infrequently in the presence of others, with the utmost freedom, upon subjects which in Western countries would never be mentioned at all. The apparent delicacy of the Chinese in regard to the relations between women and men is a' matter of ceremony, which has no perceptible effect upon speech, much less upon the thoughts. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: “Before the twentieth century, women were confined to the domestic realm, while men dominated all other aspects of society. The only exception was agriculture, where women's work had a somewhat wider definition. Western influence began to infiltrate the country in the nineteenth century, when missionaries started schools for girls. Opportunities increased further as the country began to modernize, and under communism, women were encouraged to work outside the home. Today women work in medicine, education, business, sports, the arts and sciences, and other fields. While men still dominate the upper levels of business and government and tend to have better paying jobs, women have made considerable progress. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Confucian values place women as strictly subordinate to men, and this was reflected in traditional society. Women had no rights and were treated as possessions, first of their father's and later of their husband's. The practice of foot binding was symbolic of the strictures women faced in all aspects of life. From the age of seven, girls had their feet wrapped tightly, stunting their growth and virtually crippling them in the name of beauty. This practice was not outlawed until 1901. The procedure was inflicted mainly on upper-class and middle-class women, as peasant women needed full use of their feet to work in the fields.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The division of labor by gender was nearly absolute in imperial China, except among the poorest classes. Women were barred from holding office and prevented by foot binding from many kinds of physical labor. They worked hard at domestic tasks, however, in all but the most elite families. These tasks included the production of textiles for home use and for sale, as well as some assistance in agricultural tasks and care of livestock. During the Republican period, women gained some forms of legal and educational equality and began to take on a limited number of professional positions, as well as being hired as low-wage industrial laborers. Foot binding basically disappeared by the 1930s, enabling women to do more kinds of work. [Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Improved Conditions for Women in China

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: “The rejection of many traditional values early in the twentieth century resulted in increasing equality and freedom for women. The Western presence in the nineteenth century also had an influence. Raising the status of women was a priority in the founding of the modern state. Women played an important role in the Long March and the communist struggle against the Kuomintang, and under Mao they were given legal equality to men in the home and the workplace as well as in laws governing marriage, divorce, and inheritance. Despite these legal measures, women still face significant obstacles, including spousal abuse and the practice of selling women and young girls as brides. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

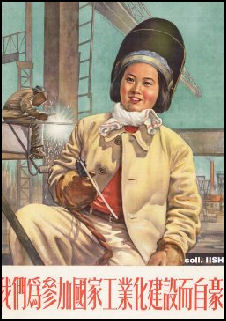

Stevan Harrell wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: ““In Communist China, women have gained full legal equality, and the participation of women in all walks of life has been a prominent feature of propaganda, especially during the Cultural Revolution. This equality probably always existed more in theory than in practice, though, and, since the Reforms, there has been some backsliding. There is much evidence of job discrimination, but it is less overt — women are considered suitable for and do pursue just about any career in business, the professions, or the public sector, but expectations that they also manage a household and care for children have kept them from achieving equality in practice.[Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

See Separate Article WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Role of Women in Modern China

In the World Economic Forum's 2018 global gender gap report, China ranked 103 out of 149 countries on the overall disparity between men and women but China’s rank rose to 86 when ranked solely for economic participation and opportunity. AFP reports: “As their economic situation improves, fewer women are choosing to get married. Although they are materially better off, the lives of many young urban women are "isolating". Most have spent their teenage years studying for the country's rigorous university entrance exams, at the cost of developing relationships outside of school. [Source: Sijia Li and Helen Roxburgh, AFP, December 6, 2019]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: “The Chinese government states that women have equal rights with men in all areas of life, and most legislation is gender neutral. However, there are continued reports of discrimination, sexual harassment, wage discrepancies, and other gender related problems.”The gap in educational level between women and men has narrowed and there are now more girls in secondary school than boys. According to the World Bank, 53 percent of graduates from tertiary education were women in 2018, collection of development indicators, compiled from officially recognized sources. [Source: World Bank, C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: “Traditionally, Chinese are respectful and courteous toward woman. One of the most powerful figures in Chinese government is a woman, Madam Wu Yi. There are parts of China where women hold dominant social position. In Shanghai, the man is the better housekeeper and cook, while the woman manages the money. There is even a functioning matriarchal village in Yunnan, where the women own all possessions and men stay with them at their wish, or return to the house of their mother. That said, there is a strong sense of gender roles between men and women in China. It is sincerely thought that they balance one another out with gender-specific characteristics. At one point when a row of women were sitting together in work cubicles and new male employees were joining, the women insisted that the man sit in between them as alternating male and female is ‘strengthening the flower, like a rose blossoming between thorns’. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Housework and Expectations of Men in China

Women in China spend nearly four hours a day doing unpaid housework, compared to men who do about 1.5 hours, according to a study from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).[Source: Katie Warren, Business Insider, February 24, 2021]

Chen Aoxue wrote in Sixth Tone: “In China perhaps even more than elsewhere, men tend to be viewed as breadwinners, while the role of spending money has generally fallen to women. This practice has, in turn, reinforced gender stereotypes that limit the roles men and women play in society, constituting a form of gender inequality. At the same time, dating in China has become increasingly expensive. According to an annual price report published by Deutsche Bank, the approximate cost of a cheap date in Shanghai this year — cab rides, lunch or dinner for two at a pub or cafe, soft drinks, two movie tickets, and a couple of beers — is $81, making the city the 32nd most expensive in the world for burgeoning romance.[Source: Chen Aoxue, Sixth Tone, June 29, 2017. Chen is a student in the School of Management at Fudan University]

“China is still a society dominated by men, but the groundswell of feminism is growing. As my survey shows, young, well-educated female college students are gradually divesting themselves of being paid for and are looking toward a dating model whereby costs are shared more equally. I’ve learned that men are generally still permitted to play the gentleman and foot the bill, and that a majority of women won’t feel discomfited by this chivalric gesture. But hard-up male college students who balk at the constantly climbing cost of a date will surely welcome women who are willing to share expenses and not consider it an assault on their masculinity. As with the best relationships, compromise is key, and men like me are realizing that our traditional roles as breadwinners and protectors are fast becoming outdated.

Character and Changing Attitudes of Chinese Girls and Women

women academy in Shandong

Luo Yang, a photographer who has devoted much of her time to photographing Chinese girls and women, told The Beijing: I definitely feel that attitudes are changing. Girls are now braver in expressing themselves. Our advanced social media platforms also allow them to exhibit their lives in different ways. The younger generation is more individualistic and freer from the restraints that are enforced through traditions. For example, many young girls these days offer to take their clothes off during photo shoots; they are not afraid of showing off their bodies. Ten years ago I wouldn't even think about shooting nudes. Country and city girls share some common attitudes; they are independent, dream-driven, and sincere. However, [while] there is no special difference, the girls in the country give you this natural vibe, probably because they are closer to nature and more unaffected. [Source: Tom Arnstein, The Beijing, September 27, 2017]

On some of the some her subjects she said: “I first saw the cool girl Karman in a friend's photo of a party and decided to do a photoshoot with her. Before, I imagined her to be a cool, playful, fashionable party girl. It wasn’t until I started to be in contact with her that I gradually learned about her life. She was adopted as a young child and the absence of loved ones made her very sensitive and gave her very low self-esteem. During university, she decided to change her way of life, as well as take pressure off her step-parents, deciding to drop out of university and leave the city that depressed her, starting a wanderer’s life instead. She went to a lot of cities, made a lot of friends, and in her journey has been looking for love and her suppressed self.

“Ujin and I had known each other from work and also happened to be neighbors. One day she told me her story, that she and her boyfriend were having some relationship issues, remembering how in the morning he would tell her "baby, I love you" but would go off the grid at night. She decided to take her lipstick and go down into the garage to write on her boyfriend’s car “I love you, I love you” every day over a period of time. Perhaps her boyfriend was moved by her message and they got back together. This year when I met her, she was married but married to a different person. She said that when she thinks back on that time, she made such a fool of herself. Is there anyone who hasn’t been foolish in their relationships?

Wan Ying and Snow Ying are twins wh live in Chongqing. “Chongqing is a very magical city, a city with a river of such magnitude, it always fills people with the presence of lots of stories. Of the twins, the younger is a mother whereas the elder sister is still single. They share the same blood, but have significantly different personalities and went in very different directions in life. The relationship between these twins is fantastic, loving one another but also seeing a different version of oneself in each other.”

Village Women in China

Many Chinese women — hundreds of million of them — still live in the countryside. While opportunities have increased for urban women and many women migrate to the cities for work, many rural women still remain stuck in the same world and harsh life their mothers and female ancestors were stuck in. Village women have traditionally been less educated and had few options in life. Their worth in many cases is still is measured by how hard they work and whether or not they produce a son. At birth, rural girls are often regarded as disappointments by families who want a son. After that they are regarded as property of their fathers, brothers or husbands. They often address the male's in their life as masters, and can't go anywhere without their permission. Some rural women are quite strong and tough.

Women traditionally have socialized with each other, laughing and telling stories, while doing chores. When they have some free time and the means they like to meet at friends' houses and try cosmetics and fingernail polish. In rural areas rates of domestic abuse and suicide among women are high (See Suicides, Society, Life). By some estimates 80 percent of the murder deaths are the result of conflicts between husbands and wives. It is unusual for rural women over the age of 35 to have children. Rural Chinese women on average enter menopause five years earlier than Western women because of lifestyle, genetic and dietary factors Wang Yijue of the Sichuan Reproductive Health Research Center told the Los Angeles Times.

Women traditionally have socialized with each other, laughing and telling stories, while doing chores. When they have some free time and the means they like to meet at friends' houses and try cosmetics and fingernail polish. In rural areas rates of domestic abuse and suicide among women are high (See Suicides, Society, Life). By some estimates 80 percent of the murder deaths are the result of conflicts between husbands and wives. It is unusual for rural women over the age of 35 to have children. Rural Chinese women on average enter menopause five years earlier than Western women because of lifestyle, genetic and dietary factors Wang Yijue of the Sichuan Reproductive Health Research Center told the Los Angeles Times.

Among the daily chores performed by rural women are grooming and washing the children, preparing drinks for the men, making meals, cleaning the enclosures of animals, tending the family's crops, selling and buying stuff at the market, milking animals, making butter or cheese, collecting and processing dung, washing, pounding or winnowing rice or grain, spinning cloth, threshing, separating beans from their pods, hoeing and weeding the fields, carrying firewood, transporting the harvest, fetching water, housekeeping and looking after the children.

In many rural societies women do two-thirds of the farm labor. During the harvesting and planting season men and women work about equally but when those tasks are done women do much of the day to day farming chores while the men often goof around. Women often do so much of the farm work men are often encouraged not to come to agricultural meeting sponsored by aid workers. Women in rural areas have few opportunities to make money other than selling stuff at the market or on the streets in a town or city or performing menial labor.

One of the primary responsibilities of village women and girls is making sure there is enough water for washing, cleaning, cooking and drinking. Women carry water from a communal well or stream to their homes everyday. Most of the time there is a well in the village. But not always. Sometimes women and girls walk several miles everyday fetching water. One male villager told National Geographic, "Our women spend half their lives going for water." Village women seem to spend more time washing clothes by hand than doing anything else. From dawn to dusk the shores of lake and rivers are lined with women scrubbing, ringing and rinsing their families clothes. These women are also skilled at taking a baths in rivers and streams with their clothes on.

Rural Women in China in the 1930s, 40s and 50s

“The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past” by Gail Hershatter is the product of a decade spent conducting oral history interviews of 72 women — and a few surviving men — in rural Shaanxi province with the help of the Chinese scholar Gao Xiaoxian. The interviews focus on farming women’s experiences of political campaigns in the 1950s, ranging from land reform to the 1950 Marriage Law to agricultural collectives. The book adds individual women’s voices — often quoted at length — to the narrative of 1950s rural reform, illustrating the taffy pull between empowerment and continued discrimination that women experienced throughout the decade. [Source: Nicole Elizabeth Barnes, The China Beat, September 28, 2011, Nicole Elizabeth Barnes is a PhD candidate in modern Chinese history at the University of California, Irvine.]

Nicole Elizabeth Barnes wrote in The China Beat, “The Gender of Memory is incredibly thorough, emotionally powerful, beautifully written, theoretically innovative, and personally searching; it will have an earth-shattering effect on the study of Chinese history, calling scholars to new fields of inquiry for decades to come.”

In the book Hershatter discusses the differences in how women and men narrate their pasts, commenting that while women tend to mark their lives by personal and traumatic events such as marriage, childbirth, or death of a family member, men more commonly refer to “campaign time” and political events as the primary signposts. On this point of “gender of memory” she told China Beat, “Men and women spent their time differently, though they certainly had many shared tasks. The gendered division of labor was a constant feature of rural life, even though its content changed all the time. Men went to more meetings; women did more unpaid crucial domestic work. They remember the tasks that they performed (which differed) and the languages of political change to which they were exposed (which varied by gender, generation, location, and a host of other factors).

On the importance of spinning yarn, weaving, making clothing, Hershatter said, “In one village, handloom weaving remained common for domestic consumption and has recently made a comeback in production for the market. In another village, local embroidery of old-style wedding pillows was an important art, though it was unclear whether it was going to die out or have a resurgence as folk craft. I was given some small handkerchiefs and embroidered shoe soles, and took pictures of more elaborate embroidery.

On the hardships women endured in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, Hershatter said, “These are everyday haunting stories. Whatever the terrible shortcomings of revolutionary change — and there are many — the kinds of catastrophe that were absolutely commonplace during these women’s younger years are no longer routine or even comprehensible to their grandchildren. That’s important.

On the importance of spinning yarn, weaving, making clothing, Hershatter said, “In one village, handloom weaving remained common for domestic consumption and has recently made a comeback in production for the market. In another village, local embroidery of old-style wedding pillows was an important art, though it was unclear whether it was going to die out or have a resurgence as folk craft. I was given some small handkerchiefs and embroidered shoe soles, and took pictures of more elaborate embroidery.

On the hardships women endured in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, Hershatter said, “These are everyday haunting stories. Whatever the terrible shortcomings of revolutionary change — and there are many — the kinds of catastrophe that were absolutely commonplace during these women’s younger years are no longer routine or even comprehensible to their grandchildren. That’s important.

On perceptions of gender inequality she said, ‘some found it natural that women should be paid less than men, and had complicated reasons why. Others thought it was unjust, and had a lot to say about that. Some expressed their opinions in language provided by the state, though they used official terminology creatively. The term “feudalism,” for instance, was used by both men and women to describe behavior specific to women, which was not the way it had first been deployed. I didn’t import gender as a category of analysis — it’s a fundamental structuring device for rural Chinese. Everything I know about how gender worked in the rural Chinese 1950s, I learned through listening to stories that even an outsider could understand. What astonishes me is how anyone could think to give an account of the 1950s without attention to gender.

Women and Education in China

The gap in educational level between women and men has narrowed and there are now more girls in secondary school than boys. According to the World Bank, 53 percent of graduates from tertiary education were women in 2018. Enrollment in secondary school was 94.2 percent for males and 95.9 percent for females in 2013. In 2005, women made up 47.1 percent of college students, but only 32.6 percent of doctoral students. [Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division, genderstats.un.org; C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Now so long ago things were much worse for women seeking an education and are still bad in some rural areas. In the 1990s it was estimated that 70 percent of China's 140 million illiterates are female. In rural areas, girls were often so busy doing chores they didn't have time for school. The New York Times reported on a school in Youyan, a village in the poor Guizhou Province, and found only four of the 100 or so students were girls. "Girls at 5 to 6-years old begin a life of farm work," a teacher said.

See Separate Article CHINESE EDUCATION factsanddetails.com

Working Urban Women in China

A typical young urban woman lives with her parents and earns about $1000 month at her job, She has given half of salary to her mother, which she regards as her savings plan, and spends the rest of it on living expenses and entertainment. Her biggest expense is eating out with friends. Young working women are becoming increasingly materialistic and egocentric. Some have framed pictures of themselves on their desks. In a marketing survey, one young woman wrote, “I am the center of the world...Draw a circle and you can find me. I’m quite realistic, but sometimes I daydream. I’m a little bit selfish, but I’m always there for my friends.”

Young working women are increasingly becoming major forces in the Chinese economy. Those with good salaries, by Chinese standards, of few a hundred dollars a month think nothing of plopping down $400 for a new cell phone with the latest 3G and MP3 features or $700 on a new snowboard and gear to go with it even though they have yet to tried the sport. An economic advisor for MasterCard told Reuters, “Urban women consumers will be spending much of their hard-earned cash on personal travel and related cultural and recreational activities, dinning out, shopping, as well as buying cars and pursuing urban leisure lifestyles.”

Their spending habits, economists hope will offset the conservative spending habits of most Chinese and make the economy less reliant on investment. Favored brands by female consumers include LVMH, Christian Dior, Valentino, Swatch, Nokia and Coca-Cola. Diet medicines are popular with middle class women. They are often amphetamines. There are stories women losing 10 kilograms in a month who look wired and dazed.

See Labor

One-Child Policy a Surprising Boon for China’s Girls

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Tsinghua University freshman Mia Wang has confidence to spare. Asked what her home city of Benxi in China's far northeastern tip is famous for, she flashes a cool smile and says: "Producing excellence. Like me." A Communist Youth League member at one of China's top science universities, she boasts enviable skills in calligraphy, piano, flute and ping pong.” [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Such gifted young women are increasingly common in China's cities and make up the most educated generation of women in Chinese history. Never have so many been in college or graduate school, and never has their ratio to male students been more balanced. To thank for this, experts say, is three decades of steady Chinese economic growth, heavy government spending on education and a third, surprising, factor: the one-child policy.

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Tsinghua University freshman Mia Wang has confidence to spare. Asked what her home city of Benxi in China's far northeastern tip is famous for, she flashes a cool smile and says: "Producing excellence. Like me." A Communist Youth League member at one of China's top science universities, she boasts enviable skills in calligraphy, piano, flute and ping pong.” [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Such gifted young women are increasingly common in China's cities and make up the most educated generation of women in Chinese history. Never have so many been in college or graduate school, and never has their ratio to male students been more balanced. To thank for this, experts say, is three decades of steady Chinese economic growth, heavy government spending on education and a third, surprising, factor: the one-child policy.

In 1978, women made up only 24.2 percent of the student population at Chinese colleges and universities. By 2009, nearly half of China's full-time undergraduates were women and 47 percent of graduate students were female, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. In India, by comparison, women make up 37.6 percent of those enrolled at institutes of higher education, according to government statistics. Many single-child families are made of two parents and one daughter. With no male heir competing for resources, parents have spent more on their daughters' education and well-being, a groundbreaking shift after centuries of discrimination. "They've basically gotten everything that used to only go to the boys," said Vanessa Fong, a Harvard University professor and expert on China's family planning policy.

Beijing-based population expert Yang Juhua had studied enrollment figures and family size and determined that single children in China tend to be the best educated, while those with elder brothers get shortchanged. She was able to make comparisons because China had many loopholes to the one-child rule, including a few cities that had experimented with a two-child policy for decades. "Definitely single children were better off, particularly girls,"said Yang, who works at the Center for Population and Development Studies at Renmin University. "If the girl had a brother then she will be disadvantaged. ... If a family had financial constraints, it's more likely that the educational input will go to the sons." While her research shows clearly that it's better, education-wise, for girls to be single children, she favors allowing everyone two kids. "I do think the (one-child) policy had improved female well-being to a great extent, but most people want two children so their children could had somebody to play with while they're growing up," said Yang, who herself had a college-age daughter.

While strides had been made in reaching gender parity in education, other inequalities remain. Women remain woefully underrepresented in government, had higher suicide rates than males, often face domestic violence and workplace discrimination and by law must retire at a younger age than men. It remains to be seen whether the new generation of degree-wielding women could alter the balance outside the classroom. The problem of sex-selected abortion and even female infanticide still exist. Yin Yin Nwe, UNICEF's representative to China, puts it bluntly: The one-child policy brings many benefits for girls "but they had to be born first."

See Separate Article ONE-CHILD POLICY: ITS HISTORY AND IMPACT ON CHINA TODAY factsanddetails.com

Girls Growing Up in One-Child Policy Families

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Wang and many of her female classmates grew up with tutors and allowances, after-school classes and laptop computers. Though she was just one generation off the farm, she carries an iPad and a debit card, and shops for the latest fashions online. Her purchases arrive at Tsinghua, where Wang's all-girls dorm used to be jokingly called a "Panda House," because women were so rarely seen on campus. They now make up a third of the student body, up from one-fifth a decade ago. "In the past, girls were raised to be good wives and mothers," Fong said. "They were going to marry out anyway, so it wasn't a big deal if they didn't want to study." Not so anymore. Fong says today's urban Chinese parents "perceive their daughters as the family's sole hope for the future," and try to help them to outperform their classmates, regardless of gender. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

Things have changed a lot since Wang was born. Wang's birth in the spring of 1992 triggered a family rift that persists to this day. She was a disappointment to her father's parents, who already had one granddaughter from their eldest son. They had hoped for a boy. "Everyone around us had this attitude that boys were valuable, girls were less," Gao Mingxiang, Wang's paternal grandmother, said by way of explanation — but not apology. Her granddaughter, tall and graceful and dressed in Ugg boots and a sparkly blue top, sat next to her listening, a sour expression on her face. She wasn't shy about showing her lingering bitterness or her eagerness to leave. She agreed to the visit to please her father but refused to stay overnight — despite a four-hour drive each way.

“Fong says that many Chinese households are like this these days: a microcosm of third world and first world cultures clashing. The gulf between Wang and her grandmother seems particularly vast. The 77-year-old Gao grew up in Yixian, a poor corn- and wheat-growing county in southern Liaoning province. At 20, she moved less than a mile (about a kilometer) to her new husband's house. She had three children and never dared to dream what life was like outside the village. She remembers rain fell in the living room and a cherished pig was sold, because there wasn't enough money for repairs or feed. She relied on her daughter to help around the house so her two sons could study. "Our kids understood," said Gao, her gray hair pinned back with a bobby pin, her skin chapped by weather, work and age. "All families around here were like that." [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

But Wang's mother, Zheng Hong, did not understand. She grew up 300 kilometers (185 miles) away in the steel-factory town of Benxi with two elder sisters and went to vocational college for manufacturing. She lowers her voice to a whisper as she recalls the sting of her in-law's rejection when her daughter was born. "I sort of limited my contact with them after that," Zheng said. "I remember feeling very angry and wronged by them. I decided then that I was going to raise my daughter to be even more outstanding than the boys."

They named her Qihua, a pairing of the characters for chess and art — a constant reminder of her parents' hope that she be both clever and artistic. From the age of six, Wang was pushed hard, beginning with ping pong lessons. Competitions were coed, and she beat boys and girls alike, she said. She also learned classical piano and Chinese flute, practiced swimming and ice skating and had tutors for Chinese, English and math. During summer vacations, she competed in English speech contests and started using the name Mia. In high school, Wang had cram sessions for China's college entrance exam that lasted until 10 p.m. Her mother delivered dinners to her at school. She routinely woke up at 6 a.m. to study before class. She had status and expectations her mother and grandmother never knew, a double-edged sword of pampering and pressure. If she'd had a sibling or even the possibility of a sibling one day, the stakes might not had been so high, her studies not so intense. Some, like Wang, were already changing perceptions about what women could achieve. When she dropped by her grandmother's house this spring, the local village chief came by to see her. She was a local celebrity: the first village descendent in memory to make it into Tsinghua University. "Women today, they could go out and do anything," her grandmother said. "They could do big things."

Left Over Women (Unmarried Over Age 27) in China

Unmarried females in China are often stigmatised as "sheng nu" or leftover women. By government definition, a "leftover woman" refers to any unmarried female above the age of 27. There status has long been a topic of concern in a society that prioritises marriage and motherhood for women, especially in recent decades as the status of women has risen, views about marriage and women have changed and women insist they don’t want to get married and possibly let their careers go down the drain if they marry in their twenties.

Because China’s population is so large there has to tens of millions of unmarried women over 27 out there. The National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China (NBS) and state census figures reported approximately 1 in 5 women between the age of 25-29 remain unmarried. By comparison the figure for men is about 1 in 3. The 2010 Chinese National Marriage Survey reported that 9 out of 10 men believe that women should be married before they are 27 years old. About 7.4 percent of Chinese women between 30 and 34 are unmarried and 4.6 percent between the ages 35–39 are. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the BBC: “China's ruling Communist Party tries to urge single women to marry, to offset a huge gender imbalance caused by the recently ended one-child policy. But according to Leta Hong Fincher, author of "Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China", single Chinese women are at "a real turning point" and many are beginning to embrace a single lifestyle and push back the stigma. She told the BBC: "These are young women with strength and confidence, who are being specifically targeted by the state's deliberate campaign to pressure [them] into marrying. “Chinese women today are more educated than ever before and they are increasingly resisting marriage."

One Chinese woman said in a SK-II cosmetics video: “"In Chinese culture, respecting your parents is the most important quality. And not getting married is like the biggest sign of disrespect," shared one woman, who later broke down in tears. Another woman said: "Maybe I am being selfish. People think that in Chinese society, an unmarried woman is incomplete' “The tough stances of the parents were also featured prominently. "We always thought our daughter had a great personality. But she's just average-looking, not too pretty. That's why she's leftover," said one mother, who sat next to her daughter who tried to fight back tears.

Can the single women of China see real happy endings — where society will truly accept their choices? "At the moment, that is only a fantasy," says Ms Hong Fincher, adding that the "incredible angst, personal torture and societal pressures" depicted in the advert are still prevalent. "Marriage in China is extremely patriarchal and women need to see that being single is something to be celebrated, not to be ashamed of," she says. "But I believe that this trend of women who choose to be single and independent is going to increase and this is the beginning."

Tiny Times: A Reflection of How Materialist Chinese Women Have Become?

The “Tiny Times” series was a very successful group of relatively low-budget films that seemed to tap into a particular chord that nobody anticipated was so strong or so large. The first of the series, “Tiny Times”, released in June 2013, movie brought in $77.6 million and was the 9th biggest box office earner in China in 2013. Altogether there were four Tiny Times films. “Tiny Times 2” was released about six weeks after “Tiny Times”, “Tiny Times 3" appeared in July 2014, “Tiny Times 4" in July 2015.

Ying Zhu and Frances Hisgen wrote in China File: “The film follows four college girls as they navigate romance and their professional aspirations, but the bulk of the film is about the female longing for a life of luxury in the company of a good-looking man. “Tiny Times” is not a women’s film, though it does feature female characters, draped from head to toe in designer clothes and easily mesmerized by the presence of supposedly visually stunning males — not the usual, muscle-bound Hollywood types, but Asian boys of androgynous demeanor with compact frames, equisite facial contours and the look of perpetual youth. [Source:Ying Zhu, Frances Hisgen, ChinaFile, July 15, 2013]

“At first glance, Tiny Times might be mistaken for a Sinicized Sex and the City, but soon it becomes clear that the four boy-crazed, mall-loitering characters in Shanghai have little in common with the fiercely independent career women in Candace Bushnell’s New York. Positioned in the market by Le Vision Pictures of Beijing as a coming of age story, the rite of passage for one dazed girl in the film is to grow into a competent personal assistant to her oh-so-handsome male boss whose aloof demeanor and penetrating gaze constantly destabilizes her. Another girl from a nouveau riche family, showers her boyfriend with expensive clothes and accessories. The third girl — chubby, suffering from stereotypically low self-esteem and emotional eating — is made fun of throughout the movie as she obsesses over young tennis player, the one man in the movie who actually possesses something resembling muscle. The fourth girl, a budding fashion designer from a humble background, is trapped in an abusive relationship with yet another good-looking boy.

“Taking a page from the book of popular East Asian “idol dramas” that cater primarily to youth in their teens and twenties, the film features popular singers, actors, and actresses, cast regardless of any actual acting ability. Good idol dramas frequently feature teen romance, in which brooding characters with dark secrets and painful pasts elicit pathos and real emotion. Tiny Times, however, has done away with complex story arcs and character development. The film looks great but ultimately lacks substance.

“The four characters’ professional aspirations amount to serving men with competence. The film is a Chinese version of “chick flick” minus the emotional engagement and relationship-based social realism that typically are associated with the Hollywood genre. The only enduring relationship in Tiny Times is the chicks’ relationship with material goods. The hyper-materialist life portrayed carries little plot but serves as a setting for consumption, and is more akin to MTV or reality TV than real drama. With its scandalously cartoonish characters, the film would have worked better as a satirical comedy, except that the director is too sincere in his celebration of material abundance to display any sense of irony.

“We were caught completely off guard, stupefied by the film’s unabashed flaunting of wealth, glamor, and male power passed off as “what women want.” Its vulgar and utter lack of self-awareness is astonishing, but perhaps not too surprising. It appears to be the product of full-blown materialism in modern, urban Chinese society. The film speaks to the male fantasy of a world of female yearnings, which revolve around men and the goods men are best equipped to deliver, whether materially or bodily. It betrays a twisted male narcissism and a male desire for patriarchal power and control over female bodies and emotions misconstrued as female longing.

“Much to our horror and dark amusement Tiny Times’ male director Guo Jingming, won the award for “best new director” at the recently concluded Shanghai International Film Festival. A film school dropout turned popular fiction writer, Guo aspires to be an author of contemporary Shanghai. “Guo claims to represent the post 1990s “me generation” and has apparently hit a home run with the youth audience. According to the latest statistics from the China Film Distribution and Exhibition Association, the average age of a moviegoer in China has dropped to 21.2 years in 2012 from from 25.7 years in 2009. Tiny Times’s owes its success partly to a marketing campaign that relied heavily on social media networks reaching tens of millions of students.

“It comes as a consolation to us that the film averaged low ratings of 3.4 and 5.0 out of 10 on China's two most-visited online movie portals, mtime.com and douban.com. It was also hated by the critics, who condemned its "unconditional indolence," "materialism," and "hedonism" (People's Daily); "shallow approach, inexplicable storyline, childish characters and lavish lifestyles" (Beijing Review); "pathological greed" (Beijing News); "unabashed flaunting of wealth, glamour and male power," and "twisted male narcissism" (ChinaFile, carried also by Atlantic Online). A Guangdong Daily critic, borrowing a line from Eileen Chang, delivered the most damning review of all: "The whole film is just like 'a luxuriant gown covered with lice.'" [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin, October 12, 2013]

See Separate Article SINGLE ADULTS, LEFTOVER WOMEN AND MARRIED WITH NO CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

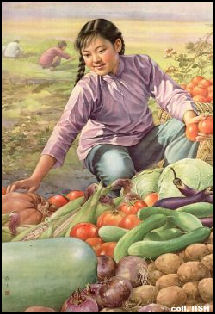

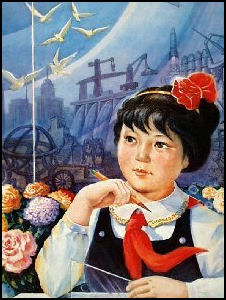

Image Sources: 1) Historical photos, Lotte Moon and University of Washington; 2) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3) Village woman, Beifan 4) Urban woman, cgstock.com http://www.cgstock.com/china ; Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021