POPULATION GROWTH AND FERTILITY IN CHINA

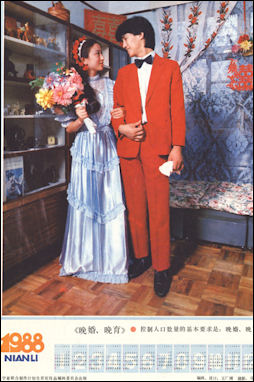

Marry Late poster According to China’s 2020 census and the National Bureau of Statistics of China: The average annual growth rate was 0.53 percent, down by 0.04 percentage point compared with the average annual growth rate of 0.57 percent from 2000 to 2010. The data showed that the population of China maintained a mild growth momentum in the past decade. The share of children rose again, proving that the adjustment of China’s fertility policy has achieved positive results. Meanwhile, the further aging of the population imposed continued pressure on the long-term balanced development of the population in the coming period. [Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, May 11, 2021]

Population growth rate in China: 0.26 percent (2021 est.); rank compared to 225 countries and territories in the world: 175. Birth rate: 11.3 births/1,000 population (2021 est.); rank compared to other countries and territories in the world: 169; Death rate 8.26 deaths/1,000 population (2021 est.); rank compared to other countries and territories in the world: 77; Net migration rate: -0.43 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2021 est.); rank compared to other countries and territories in the world: 122. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2021]

In October 2015, China ended the one-child policy at least in part to address population growth declines and boost the number of births. In 2016, China set a target of increasing its population to about 1.42 billion by 2020, from 1.34 billion in 2010. With the one-child policy eased, 17.9 million babies were born in 2016, an increase of 1.3 million over the previous year, but only half of what was expected. In 2017, the birth rate fell to 17.2 million, far below the official forecast of more than 20 million. The population growth rate in China in 2006 was 0.9 percent, compared to 2 percent in the United States, 0.8 percent in low-income countries and 1.2 percent in high-income countries. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007, Wikipedia]

Total fertility rate: 1.6 children born/woman (2021 est.). Rank compared to 225 countries and territories in the world: 185 (CIA World Factbook). The average number of children per woman was 1.75 in the 2000s (compared to 1.5 in Germany and 7.0 in Ethiopia). The average fertility rate in rural areas at that time was 1.98; in urban area it was 1.22. As a result of the one child policy, China successfully achieved its goal of a more stable and much-reduced fertility rate. In 1971 women had an average of 5.4 children versus an estimated 1.7 children in 2004. Nevertheless, the population continued to grow after the Once Child Policy was initiated in the late 1970s. China also has a significant gender imbalance. Census data from 2000 revealed that 119 boys were born for every 100 girls, and among China’s “floating population” the ratio was as high as 128:100. These situations led Beijing in July 2004 to ban selective abortions of female fetuses. Ultrasound tests to check the sex of a fetus cost as little as $15.

From 2016 to 2019, the annual birth rate mostly declined with the exception of 2016. Kevin Yao and Ryan Woo of Reuters wrote: “China has long worried about its population growth as it seeks to bolster its economic rise and boost prosperity. One bright spot in the 2020 census data was an unexpected increase in the proportion of young people — 17.95% of the population was 14 or younger in 2020, compared with 16.6% in 2010. The population increase of 5.38% to 1.41 billion measured in the 2020 census, according to Reuters, meant China narrowly missed a target it set in 2016 to boost its population to about 1.42 billion by 2020. [Source: Kevin Yao and Ryan Woo, Reuters, May 11, 2021]

Good Websites and Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China stats.gov.cn;

United Nations Population Fund unescap.org ; Trends in Chinese Demography afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Institute of Population and Labor Economics cass.cn

See Separate Articles: POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CENSUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES IN CHINA: factsanddetails.com ; BIRTH CONTROL IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SURROGATE BIRTHS, FROZEN EGGS AND IN-VITRO TREATMENTS AMONG CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; ABORTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SEX RATIO, PREFERENCE FOR BOYS AND MISSING GIRLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BRIDE SHORTAGE, UNMARRIED MEN AND FOREIGN WOMEN FOR SALE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com ; SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; END OF THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ageing Giant: China’s Looming Population Collapse” by Timothy Beardson Amazon.com; “China’s Provinces and Populations: A Chronological and Geographical Survey” by Eric Croddy Amazon.com; “China's Low Birth Rate and the Development of Population”by Guo Zhigang, Wang Feng, et al. Amazon.com; “China’s Population Aging and the Risk of ‘Middle-income Trap’” by Xueyuan Tian Amazon.com; “Governing China's Population: From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics” by Susan Greenhalgh and Edwin A. Winckler Amazon.com; “Analysing China's Population: Social Change in a New Demographic Era”by Isabelle Attané and Baochang Gu Amazon.com

Is China Inflating It’s Population Figures?

The population of mainland China was 1,411,778,724 as of November 2020 according to 2020 census in China. However the CIA World Factbook listed China’s population at 1,397,897,720 in July 2021. Sophia Yan wrote in The Telegraph: “Some academics have warned for years that China may be inflating population numbers – potentially to mask the effects of the one-child policy. Local officials were also incentivised to overestimate figures to garner more public funding. In 2020, the number of babies registered in China with the police plummeted to a record low at 10.035 million, down 15 per cent from a year prior. This has occurred even after China relaxed its family planning policies in 2015 to allow couples to have two children.[Source: Sophia Yan, The Telegraph, April 28, 2021]

The goal recently has been “to boost the number of babies born to replenish the already-shrinking labour force, the engine that propelled economic growth. At the time, family-planning authorities estimated that three million babies would be born each year between 2016 to 2021 – but the baby boom never materialised. Even local officials have flagged the sensitivity of the data. In April 2021, the deputy director of the statistics bureau in Anhui province stressed the need to “set the agenda to support how the data is interpreted, and to pay close attention to public reaction.”

In April 2021, the Financial Times reported that according to some sources who know the data of the seventh census, Chinese population in 2020 did not reach 1.4 billion. A few days later,, the National Bureau of Statistics said in a one-sentence statement that China's population increased in 2020.

Jane Li wrote in Quartz: “Around 10 million newborns were entered into Hukou, the Chinese household-registration system, in 2020 according to China’s Ministry of Public Security.This represents a 15 percent decline from the 11.8 million babies registered in 2019. Although the actual number of newborns each year would usually be bigger than the official registration figure — because some babies aren’t registered in time and hence not counted by the security ministry — many still see the decrease as evidence of China’s failure to handle its fast-approaching population crisis. China’s statistics bureau has delayed the publication of national birth data for 2020 from January to April.[Source: Jane Li, Quartz, February 9, 2021]

“In many major Chinese cities, birth data mirror the national trend. Guangzhou, a prosperous southern city that borders Hong Kong, reported a 9 percent decline in the number of newborns last year, while another nine cities saw a double-digit decline in new births during the period, according to Chinese media reports. James Liang, the chairman of China’s largest online booking service provider Trip.com and a demographic expert, calculated that 2020’s final birth number could be around 12.5 million, which would be a 15 percent decline from 2019, when around 14.7 million babies were born.

“Overall, the number of newborns in China has been on a steady decline since 2016, when Beijing officially ended the one-child policy that started in 1979. Despite a short surge in the number of births in 2016 (17.9 million), the figure has since decreased every year. If Liang’s calculation proves to be accurate, then 2020 would be the year when China saw the lowest number of births in 20 years.

Population Growth Trends and Patterns

The population of China is greater than the entire world 150 years ago. Population growth in 2007 was 0.59 percent. At that time China accounted for 11.4 percent of the world's population increase. Every year in the 2000s, the population of China increased by 14 million people (the number of people in Texas or Chile). Until recently, each decade the population of China increased by about 130 million (more than the population of Japan). In the 2000s, a about 39,000 new people were added everyday in China.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau in the 2000s the population of China was expected to reach its peak of 1.4 billion around 2026 and begin shrinking after that. According to a model by Wang Fend, a demographer at the University of California at Irvine, if current populations trend hold China’s population could shrink by almost half to 750 million. Others think the population of China is expected to peak at around 1.5 billion around 2033 when China is expected to be overtaken by India as the world’s most populous country. Others say the population is expected to start declining around 2042.

China’s population is increasing, even with the controls on family size. What is driving the growth is that hundreds of millions of Chinese are still in their reproductive years. On such a huge base, even one or two children per couple adds large numbers — an effect known as population momentum. The fertility level is expected to drop below replacement level soon. Already the population of Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and other cities would be declining were it not for the influx of migrants. Some Chinese demographers hope that China can stabilize its population and then "allow birth control and natural mortality" to reduce the population to 700 million, considered the ideal number for a nation of China’s size.

Large numbers of births occur during lucky or important years. In the year 2000, over 36 million “millennium babies” were born, nearly double the previous years. Births also spiked in 2008, the year of the Beijing Olympics, and years deemed auspicious by the Chinese calendar (See Superstitions). The trend puts pressure on hospitals, schools and job markets when large numbers are born, begin school and look for jobs at the same time

It is unusual for rural women over the age of 35 to have children. Rural Chinese women on average enter menopause five years earlier than Western women because of lifestyle, genetic and dietary factors Wang Yijue of the Sichuan Reproductive Health Research Center told the Los Angeles Times.

History of China’s Population Growth

China has been the world’s most populous nation for many centuries. One 16th century Portuguese trader wrote, the numbers of people in China were "everywhere so great that out of a tree...swarm a number of children, where a man would not have thought to have found any one at all."

When China took its first post-1949 census in 1953, the population stood at 582 million; by the fifth census in 2000, the population had almost doubled, reaching 1.2 billion. China’s population hit 1 billion in 1982. China officially recognized the birth of its 1.3 billionth citizen (not counting Hong Kong, Macau, or Taiwan) on January 5, 2005. In 2005 the population grew by 8.1 million, or 0.63 percent. China is projected to have 1.39 billion citizens by 2015, up from 1.32 billion at the end of 2008. About 23 percent of all the people on earth live in China. Every year 20 million infants are born.

China’s fast-growing population was a major policy matter for its leaders in the mid-twentieth century, so that in the early 1970s, the government implemented a stringent one-child birth-control policy. Additionally, life expectancy has soared, and China now has an increasingly aging population.

Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies”: “In 1949, when China became a communist nation, the population was about 541 million. Over the following 10 years, it increased by another 118 million. It continued to rise through the 1960s. The government encouraged this increase so China could develop water control and communication infrastructures. The government also thought increased production could help produce more food and strengthen the nation's defense. Twenty years later, the millions born during that period contributed to another baby boom. By 1970, there were roughly 830 million Chinese. The over-growing population had generated serious problems and negatively affected the national economy. [Source: Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Population Growth During the Qing Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The effectiveness of the Chinese style of rule during the Qing period [1644-1912] is most evident when one thinks about the number of people that the Qing state governed. The population of China in the 1600s, when the Manchu Qing conquered China, was somewhere in the vicinity of 100 million people. At the beginning of the 1800s, China had about 300 million people (a number that was not greatly influenced by the new areas that the Qing had added to the empire in the 18th century, which were relatively sparsely populated border regions). By the time the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, China had close to 400 million people. Thus, there was a fourfold increase in population during the period of Qing rule, yet the institutions that were put into place in the 1640s when Qing rule began (institutions largely inherited from earlier dynasties) managed to sustain a well-functioning state all the way to the fall of the empire in 1911. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Madeleine Zelin, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

Ken Pomeranz and Bin Wong wrote: “One of the real signs of the tremendous success of the Qing dynasty in the eighteenth century in what historians like to call the High Qing (1680 to about 1830 or so) was the enormous increase in population. Looking back...we tend to think of population growth as not such a great thing, but at the time, it was really looked on as a sign that the regime was doing its job. It enabled more people to come into the world, to have the satisfactions of being alive, and to live something vaguely approximating the Confucian good life. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The Qing were able to preside over a rough tripling of the Chinese population between about 1680 and maybe 1820. This growth was achieved without a decrease in the standard of living, thanks to the increasing sophistication of the economy, to state efforts to shore up regions that couldn't produce enough food for themselves, or through such areas being able to produce some other commodity that they could trade for food.

“The population grew because of various technological changes, mostly in agriculture. The Qing were very good at taxing relatively lightly in this period while providing order and making sure that very basic survival services—such as flood control— were provided, whether by the government or by private parties encouraged by the government. This population growth, in some cases, eventually became a problem. In the eighteenth century, however, it was still overwhelmingly seen as a blessing. It happened very differently in different parts of the country. The Yangzi delta, the richest part of the country, had almost zero population growth between about 1770 and 1850 for a number of reasons, including the conscious use of various methods of birth control

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The rapid growth in population” contributed “to what came to be one of the greatest weaknesses within the Qing bureaucratic system — the local magistrate. The magistrate was at the lowest level of the bureaucracy and had a very large area to control, but he was not always able to do so effectively with the resources that were given to him by the state. By the end of the Qing period, when the Chinese population had increased fourfold, a single magistrate and his office could be responsible for as many as 300,000 people.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Madeleine Zelin, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu ]

Myth of the Big Chinese Family

Ken Pomeranz and Bin Wong wrote: “One of the great myths about China is that of the Chinese family that so desperately wants a son that they have as many kids as possible and end up having enormous families. Although Chinese families did very much want sons, they were also perfectly conscious of the fact that their ability to support children was limited and that, in the long run, they didn't improve their odds by simply having the maximum number of births. And, in fact, births per woman in late imperial China are actually, on average, probably somewhat lower than in early modern Europe. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“There are various theories as to what kinds of birth control were practiced during this time. This is actually quite controversial and hard to reconstruct, but we do know that one way or another, they seemed to keep births down. This is very different from the traditional image of China as this land of Malthusian horror where, because they couldn't restrain their population, it was only kept in check by floods and famines.

“That's not the story at all. And it's again a good example of how we find the things we're trained to find. Western-trained demographers understood that in Europe, population control worked as people delayed marriage in hard times. They assumed that this was the main mechanism for fertility control available to premodern societies, so it didn't even occur to them when they looked at societies like China to think about the possibility that there might be effective birth control within marriage. Therefore, when they looked at China, they saw that access to marriage wasn't economically regulated the way it was in Europe—the average age at marriage doesn't seem to get older at hard times, women marry young anyway—and they said, "Aha, society with no control on fertility. Therefore, if fertility is unchecked, they must have had all these enormous problems of overpopulation."

“It turns out the Chinese found ways to control fertility within marriage, which many scholars thought simply did not happen before modern chemical and mechanical contraception. Population growth was concentrated not in the advanced regions of the coast, which were running out of land and realized it, but out on the frontier”.

China’s Population Policy Under Mao

Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “China's massive population is a legacy of Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, who strove to increase the ranks of the Red Army by encouraging large families and banning imports of contraceptives and declaring their use a "capitalist plot." In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a series of famines claimed tens of millions of lives. The suffering left an enduring awareness that the country couldn't sustain unlimited population growth. As Mao's power waned in the 1970s, other Chinese leaders applied the brakes. Free contraceptives were made widely available. Couples were encouraged to marry later, wait longer to have children and have fewer. In less than a decade, fertility plummeted from nearly six children per woman to fewer than three. To drive the birthrate down further, Deng Xiaoping imposed the "one-child policy" in 1979. It led to mandated abortions and other abuses by zealous enforcers. Today, there are many exceptions to the rule: Rural couples and ethnic minorities, for instance, can have two or more children. Although compulsory abortions have been forbidden, families must pay steep fines for having more children than allowed. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

Soon after taking power in 1949 Mao declared: “Of all things in the world, people are the most precious.” He condemned birth control and banned the import of contraceptives. He then proceeded to kill lots of people through vicious crackdowns on landlords and counter-revolutionaries, through the use of human-wave warfare in North Korea and through failed experiments like the Great Leap Forward.

Over time the liabilities of a large, rapidly growing population soon became apparent. For one year, starting in August 1956, vigorous propaganda support was given to the Ministry of Public Health's mass birth control efforts. These efforts, however, had little impact on fertility. After the interval of the Great Leap Forward, Chinese leaders again saw rapid population growth as an obstacle to development, and their interest in birth control revived. In the early 1960s, propaganda, somewhat more muted than during the first campaign, emphasized the virtues of late marriage. Birth control offices were set up in the central government and some provinciallevel governments in 1964. The second campaign was particularly successful in the cities, where the birth rate was cut in half during the 1963-66 period. The chaos of the Cultural Revolution brought the program to a halt, however. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the 1970s Mao began to come around to the threats posed by too many people. He began encouraged a policy of “late, long and few” and coined the slogan: “One is good, two is OK, three is too many.” In the years after his death, China began experimenting with the one-child policy. In 1972 and 1973 the party mobilized its resources for a nationwide birth control campaign administered by a group in the State Council. Committees to oversee birth control activities were established at all administrative levels and in various collective enterprises. This extensive and seemingly effective network covered both the rural and the urban population. In urban areas public security headquarters included population control sections. In rural areas the country's "barefoot doctors" distributed information and contraceptives to people's commun members. By 1973 Mao Zedong was personally identified with the family planning movement, signifying a greater leadership commitment to controlled population growth than ever before. Yet until several years after Mao's death in 1976, the leadership was reluctant to put forth directly the rationale that population control was necessary for economic growth and improved living standards.

The "Later, Longer, Fewer" policy that is the cornerstone of China's birth control program was put into effect in 1976, around the same time that Mao died. It encouraged couples to get married later, wait longer to have children, and have fewer children, preferably one. The program forced married couples to sign statements that obligated them to one child. Women who had abortions were given free vacations.

One-Child Policy in China

In 1979, three years after Mao’s death, a one-child policy was introduced to control China’s exploding population, help raise living standards and reduce the strain on scarce resources. The policy is officially credited with preventing 400 million births and keeping China’s population down to its current 1.4 billion.

Under the one-child program, a sophisticated system rewarded those who observed the policy and penalized those who did not. Couples with only one child were given a "one-child certificate" entitling them to such benefits as cash bonuses, longer maternity leave, better child care, and preferential housing assignments. In return, they were required to pledge that they would not have more children. In the countryside, there was great pressure to adhere to the one-child limit. Because the rural population accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total, the effectiveness of the one-child policy in rural areas was considered the key to the success or failure of the program as a whole. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the 1980s, 90s and 2000s posters promoting China's one-child policy could be seen all over China. One, with the slogan "China Needs Family Planning" showed a Communist official praising the proud parents of one baby girl. Another one, with the slogan "Late Marriage and Childbirth Are Worthy," showed an old gray-haired woman with a newborn baby. Others read: “Have Fewer, Better Children to Create Prosperity for the Next Generation” and "Have less children, have a better life" Slogans such as “Have Fewer Children Live Better Lives” and "Stabilize Family Planning and Create a Brighter Future” were painted on roadside buildings in rural areas. Some crude family planning slogans such “Raise Fewer Babies, But More Piggies” and “One More Baby Means One More Tomb” and "If you give birth to extra children, your family will be ruined" were banned in August 2007 because of rural anger about the slogans and the policy behind them.

In 2016 the One-Child Policy was ended and now in many cases having three kids is acceptable By the mid 2000s, China’s birth-planning laws allowed so many exceptions that many demographers considered it a misnomer to call it a “one-child” policy. Families where both parents were only children could have an extra child. People in rural areas were also allowed to bear a second child if their first child was a girl or disabled. Ethnic minorities were allowed more children. According to the policy as it was most commonly enforced at that time, a couple was allowed to have one child. If that child turned out be a girl, they were allowed to have a second child. After the second child, they were not allowed to have any more children. If they did they were fined. In some places, couples were only allowed to have one child regardless of whether it was a boy or a girl. It is still unusual for a family to have two sons.

See Separate Articles ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ONE-CHILD POLICY PROBLEMS factsanddetails.com ENDING THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Birth Patterns Before the One-Child Policy

According to Chinese government statistics, the crude birth rate followed five distinct patterns from 1949 to 1982. It remained stable from 1949 to 1954, varied widely from 1955 to 1965, experienced fluctuations between 1966 and 1969, dropped sharply in the late 1970s, and increased from 1980 to 1981. Between 1970 and 1980, the crude birth rate dropped from 36.9 per 1,000 to 17.6 per 1,000. The government attributed this dramatic decline in fertility to the wan xi shao (later marriages, longer intervals between births, and fewer children) birth control campaign. [Source: Library of Congress]

“However, elements of socioeconomic change, such as increased employment of women in both urban and rural areas and reduced infant mortality (a greater percentage of surviving children would tend to reduce demand for additional children), may have played some role. To the dismay of authorities, the birth rate increased in both 1981 and 1982 to a level of 21 per 1,000, primarily as a result of a marked rise in marriages and first births. The rise was an indication of problems with the one-child policy of 1979. Chinese sources, however, indicated that the birth rate decreased to 17.8 in 1985 and remained relatively constant thereafter.

“In urban areas, the housing shortage may have been at least partly responsible for the decreased birth rate. Also, the policy in force during most of the 1960s and the early 1970s of sending large numbers of high school graduates to the countryside deprived cities of a significant proportion of persons of childbearing age and undoubtedly had some effect on birth rates.

“Primarily for economic reasons, rural birth rates tended to decline less than urban rates. The right to grow and sell agricultural products for personal profit and the lack of an oldage welfare system were incentives for rural people to produce many children, especially sons, for help in the fields and for support in old age. Because of these conditions, it is unclear to what degree propaganda and education improvements had been able to erode traditional values favoring large families

Low Urban Fertility Rate in China

Anthony Fensom wrote in the National Interest:“Recently, more developed areas such as Beijing and Shanghai have seen fewer births than western regions such as Qinghai province, a factor linked to migration. Other areas such as the “rust belt” northeastern region, known as Dongbei, have seen a decline for economic factors, however. [Source: Anthony Fensom, National Interest, September 16, 2019]

The 2010 national census showed that the average birthrate for a Chinese household was 1.181, with the rate lower in cities and higher in rural areas. Some scholars say that number is extraordinarily low, and the real figure is probably a bit higher. According to estimates by the United Nations, the total fertility rate (the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime) from 2005 to 2010 was 1.63 on average. The Chinese government figure of 1.18 in the 2010 census is lower than the 1.4 level in Japan, while in such urban areas as Beijing and Shanghai, it even dips below 1.0. [Source: Kenichi Yoshida and Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 31, 2013; Edward Wong, New York Times, September 26, 2013]

Bloomberg reported: “China faces an urban shift that will shrink the pool of factory workers who sustain economic growth and expand the ranks of the elderly, pushing up health-care and pension costs. Higher education levels, a focus on careers, and greater expectations are causing city-dwellers to marry later and have fewer children. The falling birth rate, exacerbated by China’s three- decade-old one-child policy, will cut the number of 15- to 24- year-olds, the mainstay of factories, by 27 percent to 164 million by 2025, the United Nations estimates. In that time, those over the age of 65 will surge 78 percent to 195 million. [Source: Bloomberg News, May 31, 2012]

Shanghai’s fertility rate — the number of children the average woman in the city will bear over her lifetime — was 0.79 in the year ended October 2010, about half the national level, government statistics show. That compares with the 1.42 rate for Japan and 2.08 in the U.S.

China’s labor force is already shrinking. The number of people aged between 15 and 64 declined by 0.1 percentage point in 2011 to 74.4 percent of the population, the first contraction in 10 years, according to the official Xinhua News Agency. That’s likely to increase costs for companies in China, deterring investment and weighing on an economy that may expand at the slowest pace in 13 years in 2012. Wages for urban workers at private enterprises climbed 12 percent last year to 24,556 yuan ($3,852), the National Bureau of Statistics said on May 29.

Reasons for Population Growth Declines in China

Many Chinese are waiting to have children, or opting not to have kids at all in many cases due to the rising cost of education, health care and housing. Many aren’t even getting married. Joe McDonald and Huizhong Wu of the Associated Press wrote: “Young couples who might want to have a child face daunting challenges. Many share crowded apartments with their parents. Child care is expensive and maternity leave short. Most single mothers are excluded from medical insurance and social welfare payments. Some women worry giving birth could hurt their careers. “First, at the interview, if you are married and childless, they may ask, do you have plans to have a kid?” said He Yiwei, who is preparing to return from the United States after obtaining a master’s degree. “And then when you have a kid, you take pregnancy leave, but will you still have this position after you take the leave?” said He. “Relative to men, when it comes to work, women have to sacrifice more.” [Source: Joe McDonald and Huizhong Wu, Associated Press, May 11, 2021]

Kevin Yao and Ryan Woo of Reuters wrote: "Urban couples, particularly those born after 1990, value their independence and careers more than raising a family despite parental pressure to have children. Surging living costs in China's big cities, a huge source of babies due to their large populations, have also deterred couples from having children. According to a 2005 report by a state think-tank, it cost 490,000 yuan ($74,838) for an ordinary family in China to raise a kid. By 2020, local media reported that the cost had risen to as high as 1.99 million yuan — four times the 2005 number. "Having a kid is a devastating blow to career development for women at my age," said Annie Zhang, a 26 year-old insurance professional in Shanghai who got married in April last year. "Secondly, the cost of raising a kid is outrageous (in Shanghai)," she said, in comments made before the 2020 census was published. "You bid goodbye to freedom immediately after giving birth." [Source: Kevin Yao and Ryan Woo, Reuters, May 11, 2021]

Anthony Fensom wrote in the National Interest: Some "blame faltering traditional concepts of marriage and parenthood.” Marriage registrations have dropped each year since 2013. Meanwhile, divorces are also increasing. “Young people’s ideas of family and giving birth are changing, and traditional values such as sustaining family lineages through giving birth have been weakening,” Nankai University’s Yuan Xin told China Daily. [Source: Anthony Fensom, National Interest, September 16, 2019]

Jane Li wrote in Quartz: The falling birth rate has unleashed a debate on Chinese social media, where people are complaining about the country’s rising housing prices, stalling economy, and increasing education costs as the main reasons for not wanting to have children. “It is not to do with whether the government has policies to encourage people to have babies, it is about whether the current social environment is good enough for them to do so,” a user commented under the news on China’s Twitter-like Weibo. Indeed, amid the ever-higher pressures to raise a family, many Chinese youngsters have chosen to quit the game. The country’s marriage rate plunged to 6.6 per 1,000 people in 2019, the lowest level in 14 years. Many women have initiated campaigns on social media to encourage youngsters not to get married, as a way to show their discontent against the country’s discriminatory policies against women in the job market and higher education. [Source: Jane Li, Quartz, February 9, 2021]

“Meanwhile, the one-child policy that was in force for over three decades is still hindering the public’s willingness to have children, according to Liang of Trip.com. “The one-child policy consumed a huge amount of resources and funding, worsened the relationship between government employees [that executed the policy] and citizens,” he wrote. “Even though families are now allowed to have a second baby, it is difficult to change people’s notion of seeing one child as the norm…with the rising costs for raising children, the birth rate in China will continue to decline, and it will eventually become the country with the lowest birth rate globally.”

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Columbia University, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021