FAMOUS CHINESE WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES

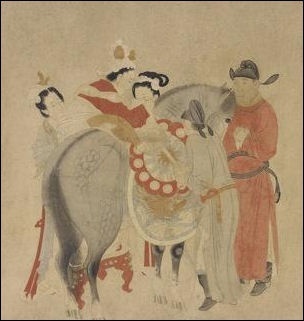

Yan Guifei, one of China's Four Beauties, mounting a horse

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “Social forces in China” have “subjugated women. And the impact can be appreciated by considering three of China’s greatest female figures: the politician Shangguan Wan’er (664-710), the poet Li Qing-zhao (1084-c.1151) and the warrior Liang Hongyu (c.1100-1135).” They “distinguished themselves in their own right—not as voices behind the throne, or muses to inspire others, but as self-directed agents. Though none is well known in the West, the women are household names in China. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015]

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: “Now China has women running multinationals and going into space but top-tier politics remains off-limits. There are no women on the standing committee of the Communist Party politburo. This may be partly because, in tales from Chinese history, women are often depicted as a danger, a threat, says Xun Zhou, a historian at Hong Kong university, who detects a tendency to blame wives for the bad luck or bad judgment of their husbands. Take Mao and his wife Jiang Qing. It's often said that Mao's only mistake was to listen to Jiang Qing in old age. "But in fact Jiang Qing was just Mao's tool," says Xun. "Mao was really behind all of it but this is how in China they see women." And then there is the case of Gu Kailai, wife of the disgraced Chongqing party boss, Bo Xilai, points out John Fenby. "The whole story of the poisoning of the British businessman in the hotel… it's a 'dragon lady' or Lady Macbeth scenario." Traditionally these scenarios involve dynastic rivalries at court between different concubines and their offspring. [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 11, 2012]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China” in 1899 : In one of the huge Chinese encyclopedias, out of 1,628 books, 376 are devoted to famous women, and of these four chapters treat of female knowledge, and seven others of the literary productions of women, works which have been numerous and influential. But as compared with the inconceivable numbers of Chinese women in the past, these exceptional cases are but isolated twinkles in vast interstellar spaces of dense darkness. Yet in view of the coming regeneration of China, their value as historical precedents to antiquity loving Chinese is beyond estimation. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

See Separate Articles:CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Women in Ancient China” by Bret Hinsch Amazon.com; “Women in Early Medieval China” by Bret Hinsch a Amazon.com; “Wu Zhao: China's Only Female Emperor” by N. Rothschild Amazon.com; “Wu: The Chinese Empress who schemed, seduced and murdered her way to become a living God” by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com “Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing” by Keith McMahon Amazon.com; “Women in Imperial China” by Bret Hinsch Amazon.com; “Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com; “China Under the Empress Dowager” by E. Backhouse and J.O. Bland Amazon.com; “The Dragon Empress” by Marina Warner Amazon.com; “Dragon Lady” by Sterling Seagrave Amazon.com; Madame Mao “ by Ross Terrill (Stanford) Amazon.com

Four Beauties of Ancient China

The Four Beauties or Four Great Beauties are four ancient Chinese women, renowned for their beauty. The scarcity of historical records concerning them meant that much of what is known of them today has been greatly embellished by legend. They gained their reputation from the influence they exercised over kings and emperors and consequently, the way their actions impacted Chinese history. Three of the Four Beauties brought kingdoms to their knees and their lives ended in tragedy. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Four Great Beauties lived in four different dynasties, each hundreds of years apart. In chronological order, they are: 1) Xi Shi (7th to 6th century BC, Spring and Autumn Period), said to be so entrancingly beautiful that fish would forget how to swim and sink away from the surface when she walks by; 2) Wang Zhaojun (1st century BC, Western Han Dynasty), said to be so beautiful that her appearance would entice birds in flight to fall from the sky; 3) Diaochan (A.D. 3rd century, Late Eastern Han/Three Kingdoms period), said to be so luminously lovely that the moon itself would shy away in embarrassment when compared to her face; and 4) Yang Guifei (719–756, Tang Dynasty), said to have a face that puts all flowers to shame. +

Xi Shi (506 B.C. – ?), originally named as Shi Yiguang, was born in Zhuluo Village, Zhuji City, Zhejiang Province during the late Spring-autumn and Warring States Period. Xi Shi was a patriotic, charming lady. In order to realize the national independence, Xi Shi was selected as a "gift" by Yue King who was the king of Yue State. She sacrificed her happiness and served Wu King who was the king of Wu State and strong opponent of Gou Jian. Wu King was so addicted to Xi Shi that he ignored all the national affairs. Day by day, Wu State gradually fell in decay. Yue King seizes the excellent chance and defeated Wu King, realizing the dream of national independence. [Source: CITES]

Wang Zhaojun, also known as Wang Qiang, was born in Baoping Village, Zigui County (in current Hubei Province) in 52 B.C. in the the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–8 AD). She was a gorgeous lady and great at painting, Chinese calligraphy, playing chess and Zheng (a kind of musical instrument in ancient China). In 36 B.C., Wang Zhaojun was selected as royal maid to serve the royal members. At that time, the Han Empire was having conflicts with Xiongnu, a nomadic people from Central Asia based in present-day Mongolia. Before her life took a dramatic turn, she was a neglected palace lady-in-waiting, never visited by the emperor. In 33 B.C., Hu Hanye, leader of the Xiongnu paid a respectful visit to the Han emperor, asking permission to marry a Han princess, as proof of the Xiongnu people's sincerity to live in peace with the Han people. Instead of giving him a princess, which was the custom, the emperor offered him five women from his harem, including Wang Zhaojun. No princess or maids wanted to marry a Xiongnu leader and live a distant place so Wang Zhaojun stood out when she agreed to go to Xiongnu.

Unlike the other three Great Beauties of China, there is no known evidence that suggests Diaochan’s existence; therefore she is regarded as a fictional character. Diaochan appears in Luo Guanzhong's historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms in a plot involving the warrior Lü Bu and the warlord Dong Zhuo. According to historical records, Lü Bu did have relations with one of Dong Zhuo's servant maids. However, there is no evidence that the maid's name was "Diaochan". In fact, it is extremely unlikely that it was Diaochan, because "Diao" is hardly used as a Chinese family name. "Diaochan" likely referred to the sable (diao) tails and jade decorations in the shape of cicadas (chan), which at the time adorned the hats of high-level officials.

The great Tang Dynasty Emperor Xuanzong was dominated by his concubine known as Yang Guifei (A.D. 719-756), a name that means “Imperial Concubine Yang” (Yang Guifei), with “Guifei” being the highest rank for imperial consorts during her time. She was born in an old, well-known official family. She was gifted in music, singing, dancing and playing lute. These talents, it is said, together with her education, made her stand out among the imperial concubines and win the emperor's favor. Jade ("yu") was considered so precious that it was often used in women's names. Yang's other common name — Yang Yuhuan — means "jade ring."

See Separate Article FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA: XI SHI, WANG ZHAOJUN, DIAOCHAN, YANG GUIFEI factsanddetails.com

Empress Wu Zetian

Empress Wu Zetian (625–705) was the empress of China from A.D. 690 to 705. She is the only woman in Chinese history to rule in her own right. and . She usurped the throne in 690 and died in 705 at age 81. The daughter of a Shanxi lumber dealer, she grew up in Shaanxi and was briefly a nun before she worked her way up to empress from a low-ranking concubine. Regarded as a tyrant, she reportedly killed many of her rivals and changed the name of the dynasty from Tang to Chou (or Zhou). It was changed back after she died.

Empress Wu Zetian was the only female emperor in Chinese history. Her story has intrigued many in China, and has been the subject of a TV series. She expanded China, improved international relations and trade, raised the status of women and encouraged the arts. Under her rule great works of art such as Buddhist statuary, mounted dolls playing musical instruments, gold and silverworks, ceramics and glassware were produced. She reportedly had her own harem of men and is famous for being tactful with her husbands.. She was ultimately forced off the throne by a coup in 705 orchestrated by one of her sons.

Originally a low-ranked concubine, Wu allegedly rose to power after killing her own baby daughter. Wu spent years consolidating her power and ruling behind the scenes. In 690, after Gaozong had been dead for some time and she had forced two of her sons off the throne, Wu became the official emperor of China. While condemned for her ruthlessness and violent tactics, she is credited for the stability of her reign, her reform of the civil service examinations, and her policy of keeping nationwide suggestion boxes in which ordinary subjects were allowed to criticize government officials.[Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, May 16, 2016]

See Separate Articles WU ZETIAN, EMPRESS WEI AND YANG GUIFEI: GREAT WOMEN OF THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com

Empress Wei

Empress Wei (died 710) was an empress and the second wife of Emperor Zhongzong, who reigned twice. She was in charge of running the government during her husband's reign. In his second reign, she attempted to emulate her mother-in-law Wu Zetian and seize power. After Emperor Zhongzong's died in 710 — a death traditionally attributed to poisoning — she attempted to to take power as the empress dowager and regent. Not long afterward she was overthrown and killed in a coup led by Emperor Zhongzong's nephew Li Longji, who later became Emperor Xuanzong. [Source: Wikipedia]

In 698, Wu Zetian decided to make Li Zhe crown prince and she summoned Li Zhe and his family out of exile. In spring 705, when Wu Zetian being ill, she was forced to yield the throne back to Li Zhe (then named Wu Xin). He was returned to the throne as Zhongzong, restoring Tang Dynasty, when Wu Zetian died in 705. Wei became empress and quickly became very powerful. She plotted against her enemies and her enemies plotted against here. She had affairs with officials and people were poisoned, forced to commit suicide and exiled. People were killed for revenge and implicated in plots they were not really involved in, and killed in brutal or cruel fashion for that. Li Chongjun, the crown prince, was humiliated and harassed by Wei and called a slave. Li raised an army and tried to kill Empress Wei but instead he was killed by his own subordinates.

In 710, Emperor Zhongzong died after eating poisoned. Empress Wei did not initially announce his death, but instead placed a number of her cousins in charge of the imperial guards, to secure power, before she announced Emperor Zhongzong's death two days after his death. Emperor Zhongzong's son Li Chongmao took the throne as Emperor Shang and Empress Wei retained power as empress dowager. Empress Dowager Wei's clan members urged her take the throne, like Wu Zetian did and eliminate Zhongzong’s closest relatives. An official leaked their plan and Zhongzong’s relatives responded by killing Empress Wei’s relatives. Empress Dowager Wei panicked and fled to an imperial guard camp where she was beheaded by a guard. More of here relatives were killed and Wei and was posthumously reduced to commoner rank. Still Emperor Ruizong buried her with honors (so some historians refer this as an evidence that she never poisoned Zhongzong), but not with honors due an empress, rather with honors due an official of the first rank. Films with Empress Wei include “Deep in the Realm of Conscience” (2018), “The Greatness of a Hero” (2009). “Palace of Desire” (2000) and “The Blood Hounds” (1990).

Shangguan Wan’er (664-710)

Foreman wrote, “Shangguan began her life under unfortunate circumstances. She was born the year that her grandfather, the chancellor to Emperor Gaozong, was implicated in a political conspiracy against the emperor’s powerful wife, Empress Wu Zetian. After the plot was exposed, the irate empress had the male members of the Shangguan family executed and all the female members enslaved. Nevertheless, after being informed of the 14-year-old Shangguan Wan’er’s exceptional brilliance as a poet and scribe, the empress promptly employed the girl as her personal secretary. Thus began an extraordinary 27-year relationship between China’s only female emperor and the woman whose family she had destroyed.” [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

“Wu eventually promoted Shangguan from cultural minister to chief minister, giving her charge of drafting the imperial edicts and decrees. The position was as dangerous as it had been during her grandfather’s time. On one occasion the empress signed her death warrant only to have the punishment commuted at the last minute to facial disfigurement. Shangguan survived the empress’s downfall in 705, but not the political turmoil that followed. She could not help becoming embroiled in the surviving progeny’s plots and counterplots for the throne. In 710 she was persuaded or forced to draft a fake document that acceded power to the Dowager Empress Wei. During the bloody clashes that erupted between the factions, Shangguan was dragged from her house and beheaded.” \~\

“A later emperor had her poetry collected and recorded for posterity. Many of her poems had been written at imperial command to commemorate a particular state occasion. But she also contributed to the development of the “estate poem,” a form of poetry that celebrates the courtier who willingly chooses the simple, pastoral life. Shangguan is considered by some scholars to be one of the forebears of the High Tang, a golden age in Chinese poetry. \~\

Li Qing-zhao (1084-c.1151)

Foreman wrote: Li Qingzhao “lived during one of the more chaotic times of the Song era, when the country was divided into northern China under the Jin dynasty and southern China under the Song. Her husband was a mid-ranking official in the Song government. They shared an intense passion for art and poetry and were avid collectors of ancient texts. Li was in her 40s when her husband died, consigning her to an increasingly fraught and penurious widowhood that lasted for another two decades. At one point she made a disastrous marriage to a man whom she divorced after a few months. An exponent of ci poetry—lyric verse written to popular tunes, Li poured out her feelings about her husband, her widowhood and her subsequent unhappiness. She eventually settled in Lin’an, the capital of the southern Song.” [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

Li’s later poems became increasingly morose and despairing. But her earlier works are full of joie de vivre and erotic desire. Like this one attributed to her:

...I finish tuning the pipes

face the floral mirror

thinly dressed

crimson silken shift

translucent

over icelike flesh

lustrous

in snowpale cream

glistening scented oils

and laugh

to my sweet friend

tonight

you are within

my silken curtains

your pillow, your mat

will grow cold.

“Literary critics in later dynasties struggled to reconcile the woman with the poetry, finding her remarriage and subsequent divorce an affront to Neo-Confucian morals.” Li’s :surviving relics are kept in a museum in her hometown of Jinan—the “City of Springs”—in Shandong province.” /~/

Liang Hongyu (c.1100-1135)

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, Liang Hongyu “was an ex-courtesan who had followed her soldier-husband from camp to camp. Already beyond the pale of respectability, she was not subjected to the usual censure reserved for women who stepped beyond the nei—the female sphere of domestic skills and household management—to enter the wei, the so-called male realm of literary learning and public service. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

“Liang grew up at a military base commanded by her father. Her education included military drills and learning the martial arts. In 1121, she met her husband, a junior officer named Han Shizhong. With her assistance he rose to become a general, and together they formed a unique military partnership, defending northern and central China against incursions by the Jurchen confederation known as the Jin kingdom. \~\

“In 1127, Jin forces captured the Song capital at Bianjing, forcing the Chinese to establish a new capital in the southern part of the country. The defeat almost led to a coup d’état, but Liang and her husband were among the military commanders who sided with the beleaguered regime. She was awarded the title “Lady Defender” for her bravery. Three years later, Liang achieved immortality for her part in a naval engagement on the Yangtze River known as the Battle of Huangtiandang. Using a combination of drums and flags, she was able to signal the position of the Jin fleet to her husband. The general cornered the fleet and held it for 48 days. \~\

“Liang and Han lie buried together in a tomb at the foot of Lingyan Mountain. Her reputation as a national heroine remained such that her biography was included in the 16th-century Sketch of a Model for Women by Lady Wang, one of the four books that became the standard Confucian classics texts for women’s education. Though it may not seem obvious, the reasons that the Neo-Confucians classed Liang as laudable, but not Shangguan or Li, were part of the same societal impulses that led to the widespread acceptance of foot-binding. First and foremost, Liang’s story demonstrated her unshakable devotion to her father, then to her husband, and through him to the Song state. As such, Liang fulfilled her duty of obedience to the proper (male) order of society. \~\

“The Song dynasty was a time of tremendous economic growth, but also great social insecurity. In contrast to medieval Europe, under the Song emperors, class status was no longer something inherited but earned through open competition. The old Chinese aristocratic families found themselves displaced by a meritocratic class called the literati. Entrance was gained via a rigorous set of civil service exams that measured mastery of the Confucian canon. Not surprisingly, as intellectual prowess came to be valued more highly than brute strength, cultural attitudes regarding masculine and feminine norms shifted toward more rarefied ideals. \~\

Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi (1835 – 1908) was a Chinese empress dowager and regent who effectively controlled the Chinese government in the late Qing dynasty for 47 years, from 1861 until her death in 1908. A member of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, she was selected as a concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor in her adolescence and gave birth to a son, Zaichun, in 1856. After the Xianfeng Emperor's death in 1861, the young boy became the Tongzhi Emperor, and she became the Empress Dowager. Cixi secured power by ousting a group of regents appointed by the late emperor and assumed regency, which she shared with Empress Dowager Ci'an. Cixi then consolidated control over the dynasty when she installed her nephew as the Guangxu Emperor at the death of the Tongzhi Emperor in 1875, contrary to the traditional rules of succession of the Qing dynasty that had ruled China since 1644. [Source: Wikipedia]

In 1861, when a powerful leader could have turned the country around, the Chinese throne was taken over by a succession of child emperors who were controlled by a former concubine known as the Empress Dowager Cixi. Cixi is the title of honor for the Empress Dowager in late Qing dynasty. Her real name was Yulan, but people (except her husband and parents) were forbidden to call her Yulan, according to the complex rules of feudal system.

Less than five feet tall and known to ordinary Chinese as "that evil old woman," the “dragon lady” and “old master Buddha”, Cixi rose from the position of a third-level concubine to become the ostensible ruler of China for nearly half a century by bearing the Emperor of China his only son. Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “One of Emperor Xianfeng's 3,000 concubines, Cixi rose through the ranks by producing an heir, Tongzhi, and when Xianfeng died in 1861 she ousted other contenders and installed herself as sole regent for her son, ruling China for 47 years.. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013]

See Separate Article EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI: HER LIFE, LOVERS AND EXTRAVAGENT LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com CHINA UNDER THE EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI factsanddetails.com

Jiang Qing

Mao's forth wife,Jiang Qing, was a major force behind the Cultural Revolution and a member of the Gang of Four. She is remembered as a power-hungry, narcissistic, and vengeful old women who was driven to extremism by the humiliation of Mao's endless womanizing.

Jiang is sometimes referred to as Madame Mao and has been variously described as the White-Boned Demon, and a Marxist-Leninist Eva Peron. Jiang once declared ‘sex is engaging in the first rounds, but what really sustains attention in the long run is power.” Anchee Min, author the novel Becoming Madame Mao told the New York Times, "She's the concubine who gets too much power and destroys the dynasty. It's a very old story in China."

Jiang Qing was a member of the Gang of Four and some say she was one of the masterminds of the Cultural Revolution. According to some scholars the whole ordeal grew out of an attempt to extrapolate her radical ideas about the arts to society as a whole and became an experiment that went out of control.

Others disagree and say Mao was the mastermind. One bodyguard said: “Jiang Qing could only make suggestions not decisions.” Some believe that she made a kind of deal with Mao in that she would look the other towards his philandering’she once caught him in bed with one of her nurses and for a while was only allowed to speak to him through his mistress if he gave her radical leftist political ideas support.

See Separate Articles MAJOR FIGURES OF THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com GANG OF FOUR TRIAL factsanddetails.com

Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Known to some people as the "Dragon Lady," Soong Mei-ling was born in 1897 in Shanghai. She grew up in Piedmont, Georgia in the United States and graduated from Wellesley College in 1917. Her English was better than her Chinese.

In 1936,Madame Chiang Kai-shek came to her husband's rescue when he was held hostage by rebel troops sympathetic with the Communists. She is also believed to have played a part in convincing her husband to form an alliance with the Communists to fight the Japanese. At one point, she led the Chinese air force.In the 1920s Madame Chiang Kai-shek set up schools for orphans of the revolutionary army. During the eight-year war with Japan, she visited combat units and hospitals.

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: Mei-ling “became a convenient hate figure for China's leftists. Until the reform era in the 1980s, all good communists were taught that she was a wicked bourgeois. "As I was growing up, she was seen as a bad character," says Xun Zhou. "They always referred to those beautiful dresses - she used make-up and wore necklaces, all those things, as bourgeois elements do. And also she was on the nationalist side, which was the enemy." \~/

Chairman Mao died in 1976 and the idea of socialism with Chinese characteristics was dreamed up to bridge the divide between capitalism and communism. Make-up and necklaces didn't seem so wicked after all, and Meiling was rehabilitated. "In the past 10 or 15 years, she's more represented as this modern, beautiful, intelligent woman. In fact, there's probably more talk about her than her sister Qingling now." \~/

See Separate Article SOONG SISTERS AND MADAME CHIANG KAI-SHEK factsanddetails.com

Gu Kailai: Bo Xilai's Wife

China's most significant political development in the 2000s and 2010s in many ways was scandal that broke in early 2012, involving Bo Xilai, the ambitious and charismatic Chongqing party boss who made a name for himself as an anticorruption and crime fighter and somehow combined neo-Maoist populism with business-friendly policies. He was removed as Chongqing’s party leader after his deputy fled to the U.S. consulate in February, 2012. The incident was followed by accusations of corruption and abuse of power involving Bo and his family. By April Bo had lost his party politburo and central committee posts. Bo, his wife, Gu Kailai. and his deputy were subsequently convicted in 2012 and 2013 of various charges, including murder charges against Gu Kailai. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Bo Xilai and Gu Kailai met in the early 1980s and were married in 1986, news reports have said. Bo, who was divorced at the time, had a son from his first marriage. Bo, Gu and Guagua, the couple's only child, were unusual in seeking the spotlight. Her much-photographed short, chic haircut contrasted with the frumpy look favored by most top leaders' wives. When Bo governed the port city Dalian in the 1990s, Gu ran a law firm and consultancy. Journalist Jiang Weiping, later imprisoned for documenting corruption in Bo's circle, claims her firms channeled bribes from Taiwanese and foreign investors. She went by the English name "Horus," referring to the falcon-headed Egyptian god of war, and depicted herself as a fearless attorney in her book, "Uphold Justice in America". [Source: Benjamin Kang Lim and Lucy Hornby, Reuters, August 6, 2012]

“The daughter of a revolutionary luminary, Gu, Kailai was among the first generation of lawyers educated after the Cultural Revolution, the decade of social chaos during which schools were closed, “ the New York Times reported. “Gu’s family pedigree includes a father who helped lead Communist resistance to the Japanese in the 1930s and 1940s. Married to Bo Xilai, she reveled in her brash, ambitious ways...Admirers bragged that Ms. Gu, a pioneering lawyer who spoke fluent English, was China’s answer to Jacqueline Onassis. In a nation that prefers the wives of political leaders to be bland adornments, Gu Kailai was positively fluorescent. As her husband rose through the party hierarchy, she ran successful law practice and wrote a book on the foibles of American courts “ and what she described as the ruthless efficiency of China’s legal system. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 26, August 20, 2012; Michael Wines, New York Times, May 6, 2012]

See Separate Article GU KAILAI (BO XILAI'S WIFE), HER TRIAL AND THE NEIL HEYWOOD MURDER factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021