EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI

Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi (1835 – 1908) was a Chinese empress dowager and regent who effectively controlled the Chinese government in the late Qing dynasty for 47 years, from 1861 until her death in 1908. The main hall in the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin Hall, on the western side of the Inner Palace within the Forbidden City) is where Qing dynasty emperors received courtiers. The Eastern Chamber of Warmth is where the Empress Dowagers Cixi “reigned over China behind the curtain.” There are two thrones here with a sheet of yellow gauze between them. The child emperor the four-year-old Emperor Guangxu’sat on the throne in front while the Empress Dowager sat behind the screen in the large throne, telling the child emperor what to do. A placard in Tiananmen Square during the 1989 democratic uprising (I was there in late May during my very first trip to China!) that showed a cartoon depicting Deng Xiaoping as Cixi “ruling behind the curtain.”

Less than five feet tall and known to ordinary Chinese as "that evil old woman" and the dragon lady, "Cixi rose from the position of a third-level concubine to become the ostensible ruler of China for nearly half a century by bearing the Emperor of China his only son. A staunch anti-reformist during most of her tenure, with brief flurries of reformist activity , she was exploited by Western powers, who she claimed to despise, and brought untold hardship and despair to ordinary Chinese and oversaw the collapse of Qing (Manchu) dynasty.

Ignoring the Confucian maxim that “Women should not take part in public affairs,” Cixi had made herself China’s de facto ruler, taking control of state affairs and international relations. Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “The times that Cixi dominated were critical to the shaping of modern China, a country that resembles the Qing autocracy in many ways, though without the empire's relatively free press and anticipated suffrage. The top echelons of Chinese politics remain as male-dominated and vicious as ever, and Cixi remains as gripping a subject. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013 ***]

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu Empress Dowager Cixi: Court Life During the Time of Empress Dowager Cixi etext.virginia.edu; Wikipedia article Wikipedia Summer Palace Used by Cixi ; Wikipedia Beijing Trip.com ; Travel China Guide ; Summer Palace Factsanddetails.com/China ; Boxer Rebellion National Archives archives.gov/publications ; Modern History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall ; San Francisco 1900 newspaper article Library of Congress ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Cox Rebellion PhotosCaldwell Kvaran ; Eyewitness Account fordham.edu/halsall ; Sino-Japanese War.com sinojapanesewar.com ; Wikipedia article on the Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia

See Separate Article EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI AND HER LIFE AND LOVERS factsanddetails.com RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com : FOREIGNERS AND CHINESE IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES factsanddetails.com; SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com; BOXER REBELLION factsanddetails.com; PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com; “China Under the Empress Dowager” by E. Backhouse and J.O. Bland Amazon.com; “The Dragon Empress” by Marina Warner Amazon.com; “Dragon Lady” by Sterling Seagrave Amazon.com; “Décadence Mandchoue: The China Memoirs of Sir Edmund Trelawny Backhouse” by Edmund Trelawny Backhouse and Derek Sandhaus Amazon.com; "The Boxer Rebellion" by Diana Preston. Amazon.com; “The Siege at Peking” by Peter Fleming, David Shaw-Parker Amazon.com; “The Last Manchu: The Autobiography of Henry Pu Yi, Last Emperor of China” by Paul Kramer, Henry Pu Yi, et al. Amazon.com; “My Husband Puyi: The Last Emperor of China” by Qingxiang Wang Amazon.com; Film: “Last Emperor” Amazon.com

Was Cixi a Decent Leader or Indulgent Villian?

The jury is still out on Cixi's legacy. Some have depicted her as cruel and oppressive, the person most to blame for the end of Qing the dynasty, but others give her credit for introducing changes and reforms. Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “One of Emperor Xianfeng's 3,000 concubines, Cixi rose through the ranks by producing an heir, Tongzhi, and when Xianfeng died in 1861 she ousted other contenders and installed herself as sole regent for her son, ruling China for 47 years....The times that Cixi dominated were critical to the shaping of modern China, a country that resembles the Qing autocracy in many ways, though without the empire's relatively free press and anticipated suffrage. The top echelons of Chinese politics remain as male-dominated and vicious as ever, and Cixi remains as gripping a subject. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013 ***]

In her book “Empress Dowager Cixi, Jung Chang, the author of “Wild Swans” sets out to rehabilitate the reputation of a woman who, she argues, helped modernize China. The New Yorker reported: Cixi seized power in 1861, after her five-year-old son ascended to the throne. Under her leadership, China opened up to Western trade and ideas and experienced a surge of prosperity. Over the next forty-seven years, her influence fluctuated, as first her son and then an adopted son assumed power, but her political sense always remained acute. While Chang acknowledges Cixi’s missteps—such as allowing the Boxers to fight against a Western invasion, which led to widespread slaughter—she sees her as a woman whose energy, farsightedness, and ruthless pragmatism transformed a country. [Source: The New Yorker, January 13, 2014]

A member of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, she was selected as a concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor in her adolescence and gave birth to a son, Zaichun, in 1856. After the Xianfeng Emperor's death in 1861, the young boy became the Tongzhi Emperor, and she became the Empress Dowager. Cixi secured power by ousting a group of regents appointed by the late emperor and assumed regency, which she shared with Empress Dowager Ci'an. Cixi then consolidated control over the dynasty when she installed her nephew as the Guangxu Emperor at the death of the Tongzhi Emperor in 1875, contrary to the traditional rules of succession of the Qing dynasty that had ruled China since 1644. [Source: Wikipedia]

China at the Time of the Empress Dowager Cixi

Emperor Xianfeng

Until 1850 or so, most Chinese believed the world was flat. "By the end of the 19th century the pressure from the world of ideas," wrote Yale history professor Jonathan Spence in Time magazine, "had led to strident and insistent demands for new structures of justice, new realms of freedom of aesthetic endeavor and the dissemination of information, and abandonment of autocracy for either a genuinely circumscribed constitutional monarchy or popularly passed republican form of government."

In late imperial times the agricultural land in the north was worked by people who owned the land while the land in the south was owned by landlords who didn’t work the land themselves. Peasants who worked the land in the south either paid a fixed rent in crops or a fixed rent in cash or paid their landlords with a share of their harvest. It was more of commercial operation than a feudal one. In the north peasants paid high agricultural taxes that were not abolished until 2006.

The threat presented by colonialism and Western power, forced the Chinese to take a hard look at themselves and re-evaluate their system of beliefs. In many cases traditional ideas about Confucianism, the Mandate of Heaven and authority were tossed out and Western ideas of capitalism, modernism, militarism and ultimately socialism and Marxism were embraced.

Empress Dowager Cixi Secures Power

The Empress turned out to be barren. While the Emperor was on his deathbed, Cixi pleaded with him to name her son as his successor. Recalling the moment Cixi later said, "I took my son to his bedside and asked him what he was going to do about his successor to the throne...I said to him, 'Here is your son; on hearing which he immediately opened his eyes and said, 'Of course he will succeed to the throne."

The Emperor stayed true to his word and arranged for Cixi (now the empress dowager) and eight regents to run the court while his son (now Tongzhi or T'ung Chih) grew up.

After the Emperor died in 1861, Cixi was named an empress dowager and Tongzhi’s co-regent. Working with her brother-in-law Yi Xin, she launched a palace and wiped out her political enemies. She effectively seized power by ordering the arrests of the eight regents and arranging the forced suicides of two of them with silk ropes. She then outmaneuvered a rival empress dowager and ruled the court behind the scenes through a "bamboo curtain." Tongzhi was five when the Emperor died. He ascended to the throne at the age of 18 but died of small pox or syphilis two years later.

Cixi was a master of court politics and intrigue and managed by keep her power even after her son died. After he died Cixi presided over the Grand Council and pushed through her choice for emperor: Guangxu, her three-year-old nephew (the son of her sister and a prince). When he ascended to the throne she went briefly into retirement and he developed a fascination with Western technologies, particularly clocks and bicycles. She directed state affairs from behind the screen during reigns by Tong Zhi and Guang Xu for 48 years.

Niuyoulushi, another empress of Emperor Xian Feng, was respected as Empress Dowager Ci An after Xian Feng died. Together with Empress Dowager Ci Xi, she attended to state affairs behind the screen after the coup in 1861. But military and political powers were retained by Ci Xi. In 1881, Ci An died in Zhongcuigong. Cause of her death was a mystery.

Cixi’s Rule

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “Formally, Cixi had no power, but she succeeded in mounting a coup against the regents with Empress Zhen, the late emperor's principal wife, before he was buried. Cixi falsely accused the regents of forging the emperor's will, and in the first of what would be a substantial list of Cixi fatalities, ordered the suicide of the most important two. Her son was crowned Emperor Tongzhi, and Cixi's extraordinary political career was launched. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013 ***]

“Since she could never sit on the throne herself, her continued power depended on the emperor being a child. In this, one might say, she had a lot of luck. Her own son died as a teenager in 1875 and another child, her three-year-old nephew, succeeded as Emperor Guangxu. Cixi promptly adopted him, though, bizarrely, she instructed him to address her as "my royal father". It was not a warm relationship. The death of the former empress Zhen, which some would add to Cixi's account, left Cixi in sole charge and her reluctance to hand over the reins on the boy's maturity was palpable. She reluctantly "retired" in 1889 and devoted herself to building a pleasure ground on the outskirts of Beijing. It was not the last of her. She came out of retirement to help with the trauma of a lost war against Japan in 1894, after which she retained an active role in state affairs, a position that left her well placed for her next coup. ***

Cixi’s biographer Jung Chang wrote: "In some four decades of absolute power, her political killings, whether just or unjust … were no more than a few dozen, many of them in response to plots to kill her." According to Hilton, “ Life at any court is a rough game: the combination of intimate emotions and absolute power generates a special form of cruelty in those who survive. A woman who began her adulthood as a 16-year-old grade-three imperial concubine in 1852, and rose to hold supreme power in the Manchu empire for the best part of 40 years, is likely to have a few unpleasant traits. Nevertheless, a few dozen political murders – without counting the deaths further afield in suppressed rebellions and more distant wars – is not nothing. Her victims included the emperor Guangxu's son's favourite concubine, thrown down a well, and Guangxu himself, by then deposed by her, dispatched with arsenic on the eve of her own death to ensure that he made no comeback. ***

China Begins Modernizing

First Shanghai train

After consolidating control over the dynasty, Cixi supported the Self-Strengthening Movement – a period of institutional economic and military reforms, which helped transform China from a medieval society into a more modern power.

In the late 1800s China began imitating Western technology. The Chinese were especially anxious to learn the European trades of shipbuilding and gunsmithing. In the 19th century a reformist named Feng Gui-fen said: "A few barbarians should be employed and Chinese who are good in using their minds should be selected to receive instructions so that in turn they may teach many craftsman...We should use the instruments of the barbarians, but not ape the ways of the barbarians. We should use them so we can repel them."

Not everyone believed that imitating the West was the answer to China's problems. In his 1919 travelogue "Travel Impressions of Europe", the Chinese traveler Liang Chi'ch'ao wrote: "We may laugh at those old folks among us who block their own road to advancement and claim we Chinese have all that is found in Western learning. But we should laugh even more at those who are drunk with Western ways and regard everything Chinese as worthless, as though we in the last several hundred years have remained primitive and have achieved nothing?"

Among the leading reformists in the late 19th century and early 20th century were Zheng Guanying, who helped China build its first series of modern industries; Wang Tao, a thinker and publisher of China’s first modern newspaper; and Liang Qichao, a key figure in the Hundred Day Reform 1898 and the constitutional movement that led to the drafting of China’s first constitution in 1908

Li Hongzhang, the Chinese foreign minister of the late 19th century, had to make various compromises on Chinese sovereignty, including cession of railway rights to Russia, which led to his being reviled by his contemporaries. A century later, Li's reputation is still controversial in China, but he is widely regarded as an original thinker who played a difficult hand with skill.

Guangxu and Attempts at Reform in China

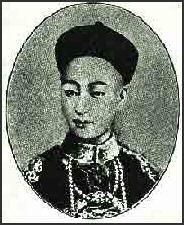

Guangxu, the second to last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, is best known for his unsuccessful attempt to modernize China by instituting reforms to the system of government in 1898, the so-called Hundred Days Reform aimed to adopt a constitutional monarchy. The reforms turned out to be short-lived, just like the emperor himself.

Enlightened Qing Dynasty statesman tried to introduce Western technology and modernize China while keeping the Qing dynasty intact. Ignoring conservatives in his court, the 27-year-old Emperor Guangxu launched a reform movement called Hundred Day Reform in 1898 in which he set about abolishing institutions that had held back China's progress. As part of his modernization campaign he hoped to establish transportation networks, beef up the military, translate Western books, educate the masses and get rid of "bigoted conservatism and impractical customs."

Guangxu as a child

The reforms failed when the Empress Dowager Cixi staged a palace coup and Emperor Guangxu was imprisoned in the Hall of Impregnating Vitality on an artificial island in the Forbidden City, where he studied English and international affairs but never again wielded any power. The coup took place on September 21, 1898 and was carried out by Manchu generals and members of the Manchurian elite. Once installed as the leader of China, the Empress Dowager canceled all the reforms except those involving the military.

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “In 1898, Guangxu, who had good reason to dislike his "royal father" launched a radical reform programme under the guidance of two former imperial scholars, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, and against the resistance of the more conservative elements at court. Kang – portrayed here one-dimensionally as a scheming upstart – persuaded the emperor that Cixi was an obstacle that had to be neutralised. Cixi moved first: by September 1898, she had deposed and imprisoned Guangxu and taken the reins again herself. Those reformers who did not escape were executed. Also executed were two entirely innocent men, whose trials Cixi had stopped to prevent the emperor's role in the plot to assassinate her becoming public. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013]

Near the end of her rule, the Empress Dowager made a few feeble attempts at reform. She ended the 2000-year-old Confucian exams system in 1905, outlawed cruel punishments, improved the legal and education system and modernized railroads. But these reforms were too little, too late. Central authority began to crumble after her death in 1908.

Hundred Days' Reform

In the 103 days from June 11 to September 21, 1898, the Qing emperor, Guangxu (1875-1908), ordered a series of reforms aimed at making sweeping social and institutional changes. This effort reflected the thinking of a group of progressive scholar-reformers who had impressed the court with the urgency of making innovations for the nation's survival. Influenced by the Japanese success with modernization, the reformers declared that China needed more than "self-strengthening" and that innovation must be accompanied by institutional and ideological change. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

The imperial edicts for reform covered a broad range of subjects, including stamping out corruption and remaking, among other things, the academic and civil-service examination systems, legal system, governmental structure, defense establishment, and postal services. The edicts attempted to modernize agriculture, medicine, and mining and to promote practical studies instead of Neo-Confucian orthodoxy. The court also planned to send students abroad for firsthand observation and technical studies. All these changes were to be brought about under a de facto constitutional monarchy. *

Opposition to the reform was intense among the conservative ruling elite, especially the Manchus, who, in condemning the announced reform as too radical, proposed instead a more moderate and gradualist course of change. Supported by ultraconservatives and with the tacit support of the political opportunist Yuan Shikai (1859-1916), Empress Dowager Ci Xi engineered a coup d'etat on September 21, 1898, forcing the young reform-minded Guangxu into seclusion. Ci Xi took over the government as regent. The Hundred Days' Reform ended with the rescindment of the new edicts and the execution of six of the reform's chief advocates. The two principal leaders, Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929), fled abroad to found the Baohuang Hui (Protect the Emperor Society) and to work, unsuccessfully, for a constitutional monarchy in China. *

See Separate Article MODERNIZATION AND REFORM EFFORTS IN CHINA IN THE LATE 1800s AND EARLY 1900s factsanddetails.com

Decisions and Eunuchs in the Empress Dowager's Court

Empress Cixi's eunuchs

Describing the decision making process of Empress Dowager Cixi, one courtier said, "In the morning an order is issued; in the evening it is changed. Unavoidably outsiders will laugh, But there is nothing that can be done about it." Another court member said: "She is very changeable; she may like one person today, tomorrow she hates the same person worse than poison."

Describing her temper on official said, her eyes "poured out straight rays; her cheekbones were sharp and the veins on her forehead projected; she showed her teeth as if she were suffering from lockjaw." Another court member said, "It was characteristic of Her Majesty to experience a keen sense of enjoyment at the troubles of other people."

With the exception of the Emperor, the 6,000 residents of the Forbidden City were eunuchs or women. Much of the day to day operation of the imperial court was taken care by Li Liyang, the Empress Dowager's favorite eunuch. He headed an imperial staff that oversaw thousands of cooks, gardeners, laundrymen, cleaners, painters and other eunuchs that were ordered around in a complex hierarchy with 48 separate grades.

"Each eunuch was apprenticed to a master," wrote Marina Warner, biographer of the Empress Dowager, "and his eventual success or promotion depended on the favor in which his master was held. On his master's death, a young eunuch might be forgotten...until the day he himself died but if he was apprenticed to the chief he might rapidly acquire influence."

Empress Dowager Cixi and the Boxer Rebellion

At the end of the 19th century China existed as a nation in name only. The Qing dynasty controlled only parts of China and the rest of China was divided among warlords and foreigners who controlled different parts of the country. As the Qing dynasty fell apart more and more of China was wrestled from its control. The Qing dynasty was weakened by the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion. In 1900 the Boxer Rebellion occurred.

Cixi's biggest mistake was to encourage the disastrous Boxer rebellion, a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian movement that culminated in a bloody siege of the foreign legations in Beijing. The Empress Dowager supported the rebellion and at one point declared war against the United States, Japan and seven European countries. In her book “The Boxer Rebellion”, Diana Preston wrote of the Empress Dowager: "On the one hand she was afraid of the Boxers because they threatened her rule. She couldn't control them. On the other hand, they represented a growing and highly motivated army she didn't have to pay, one that might help her 'purify' China of its corrupting foreign influences." Her own troops finally joined the Boxers.

Many historians believe that Cixi’s support of the Boxers was prompted by plans by Emperor Guangxu to implement serious reforms. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “When the empress Cixi saw that the emperor was actually thinking about reforms, she went to work with lightning speed. Very soon the reformers had to flee; those who failed to make good their escape were arrested and executed. The emperor was made a prisoner in a palace near Beijing, and remained a captive until his death; the empress resumed her regency on his behalf. The period of reforms lasted only for a few months of 1898. A leading part in the extermination of the reformers was played by troops from Gansu under the command of a Muslim, Tung Fu-Xiang. General Yuan Shikai, who was then stationed at Tientsin in command of 7,000 troops with modern equipment, the only ones in China, could have removed the empress and protected the reformers; but he was already pursuing a personal policy, and thought it safer to give the reformers no help. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“There now began, from 1898, a thoroughly reactionary rule of the dowager empress. But China's general situation permitted no breathing-space. In 1900 came the so-called Boxer Rebellion, a new popular movement against the gentry and the Manchus similar to the many that had preceded it. The Beijing government succeeded, however, in negotiations that brought the movement into the service of the government and directed it against the foreigners. This removed the danger to the government and at the same time helped it against the hated foreigners. But incidents resulted which the Beijing government had not anticipated. An international army was sent to China, and marched from Tientsin against Beijing, to liberate the besieged European legations and to punish the government.

See Separate Article BOXER REBELLION factsanddetails.com

Empress Dowager Cixi During the Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion the Empress Dowager fled from the Forbidden City in Beijing for Xian with her court. She and the Emperor managed to slip out of the city disguised as peasants. Even though the Qing Dynasty was in ruins, foreigners kept it propped because they viewed a Qing dynasty under their control better than a potentially hostile newcomer and they saw no better alternative.

According to a famous story, after the Boxer Rebellion, when Empress Cixi was worried that European troops were going to attack the Forbidden City, she summoned Emperor Guangxu and his favorite concubine Zhen Fei and then ordered the palace evacuated. Zhen Fei begged for the Emperor to stay behind and negotiate with the Europeans. Cixi, the story goes, was enraged by the “Pearl Concubine’s” audacity and ordered some eunuchs to throw her down a well at the Forbidden City.

There is no evidence to support this story. Cixi’s great, great nephew told Smithsonian magazine. “The concubine was sharp-tongued and often stood up to Cixi, making her angry. When they were about to flee the foreign troops, the concubine said she’d remain within the Forbidden City. Cixi told her that the barbarians world rape here if she stayed, and that it was best if she escaped disgrace by throwing herself down the well. The concubine did just that.” The well is popular stop at the Forbidden City and is so small that neither story seems likely.

Cixi After the Boxer Rebellion

After the rebellion, China was forced to pay $330 million in reparations; Western armies occupied and plundered Beijing; and the Qing dynasty was forced to accept foreign armies posted in China. The United States Open Door Policy (1899) led to the American involvement in the Boxer Rebellion and other incidents around the globe and helped establish the United States as a world power. Shock waves caused by the rebellion and by the reparations demanded by the outraged world powers sent military and political convulsions through China for the rest of the 20th century.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: After the Europeans captured Beijing in 1900, the dowager empress and her prisoner, the emperor, had to flee; some of the palaces were looted. The peace treaty that followed exacted further concessions from China to the Europeans and enormous war indemnities, the payment of which continued into the 1940's, though most of the states placed the money at China's disposal for educational purposes. When in 1902 the dowager empress returned to Beijing and put the emperor back into his palace-prison, she was forced by what had happened to realize that at all events a certain measure of reform was necessary. The reforms, however, which she decreed, mainly in 1904, were very modest and were never fully carried out. They were only intended to make an impression on the outer world and to appease the continually growing body of supporters of the reform party, especially numerous in South China. The south remained, nevertheless, a focus of hostility to the Manchus. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Cixi survived the Boxer Rebellion , but with a reputation for cruelty and treachery. She needed help dealing with the foreigners clamoring for greater access to her court. So her advisers called in Lady Yugeng, the half-American wife of a Chinese diplomat, and her daughters, Deling and Rongling, to familiarize Cixi with Western ways.

Death of the Empress Dowager

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “The last few years of Cixi's career were no less dramatic and mirror the contradictions in her record. The Boxer rebellion ended in a punitive foreign rescue and huge indemnities to the countries concerned. China, and Cixi, paid a heavy price for what she later admitted was a mistake. She herself had to flee the capital, pausing only to order the killing of Guangxu's favourite concubine. When she returned to the capital she was chastened, and set about making friends with the ladies of the Legation quarter, the wives of the resident diplomats, in a belated effort to restore her reputation in the world. She launched her own reform programme within two years, using the exiled Kang Youwei's blueprint. She died in 1908, having poisoned Guangxu with arsenic the day before, thus creating what was to be the final vacancy on the Dragon throne. It was filled by the child Pu Yi, the last emperor In 1927, under the KMT (nationalist) government, Cixi's tomb was dynamited by robbers, her jewels and her teeth stolen and her body left exposed. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, October 25, 2013]

The Empress Dowager Cixi died at the age of 72 on November 15, 1908. The day after she died, court officials announced that the death of imprisoned Emperor Guangxu. The cause of his death remains a mystery. One rumor has it he was poisoned on the empress dowagers orders. According to a Penguin Biographical Dictionary of Women, she "almost certainly ordered the simultaneous death by poisoning of the young emperor and empress the day before she died in 1908."

Guangxu’s Death

Guangxu On November 11, 1908, the 37-year-old emperor died suddenly in the Summer Palace where he had been under house arrest since 1898, when the Empress Dowager Cixi launched a coup against him. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: When she felt that her end was near, she seems to have had the captive emperor Guangxu assassinated (at 5 p.m. on November 14th); she herself died next day (November 15th, 2 p.m.): she was evidently determined that this man, whom she had ill-treated and oppressed all his life, should not regain independence. As Guangxu had no children, she nominated on the day of her death the two-year-old prince P'u Yi as emperor (reign name Hsuan-t'ung, 1909-1911). [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Even though the death was officially announced to be caused by disease, it has been the subject of speculation. Even in his own day, the cause of death was disputed. The emperor's doctor's diary recorded that Guangxu had ‘spells of violent stomach ache’, with his face turning blue. Such symptoms are consistent with arsenic poisoning. Actually, three persons were suspected behind the murder. The empress, her eunuch Li Lianying, and general Yuan Shikai, who betrayed Guangxu in the last days of the reforms and directly caused their failure. [Source: Danwei.org]

In November 2008, study released right before the 100th anniversary of Guangxu's death, concluded that that the cause of Guangxu's death was indeed arsenic poisoning. The Beijing News reported that the tests, which took five years to carry out, showed lethal doses of arsenic present in the emperor's hair and clothes, which were retrieved from his tomb. The tested arsenic level is not only higher than normal, it is also higher than the level found in a mummified body of other people living in the emperor's own time. It was also found that the arsenic levels in the roots of Guangxu's hair were higher than at the tips, thus ruling out the possibility of chronic poisoning from long term arsenic intake from medicines. “ The day after Guangxu's death, his adversary and persecutor, the Empress Dowager Cixi, also died. Could it be that knowing she was in her last days, she gave the order to kill him so that he would not outlive her? Or was it general Yuan Shikai who feared that once the emperor resumed power, he would be the first one to be eradicated for treachery? Science has no answer for these questions. “

End of the Qynasty

Just before she died in 1908, the Empress Dowager Cixi — still the de facto leader of imperial China — arranged for Emperor Guangxu’s nephew — her grandnephew Puyi — to be named the last emperor of China. On February 12, 1912, the 6-year-old child emperor of the Qing Dynasty abdicated, ending more than 2,000 years of imperial rule in China. The Qing Dynasty was brought down by a highly organized revolutionary movement with overseas arms and financing and a coherent governing ideology based on republican nationalism.

See Separate Article DECLINE AND FALL OF THE QING DYNASTY factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1) Cixi, Columbia University; 2) Shanghai train, Tales of Shanghai website; 3) Cixi, China Pag website; 4) Guangxu, Brooklyn University; 5) Summer Palace, photo Ian Patterson ; 6) Eunuchs, China Today; 7) Images from Pu yi website

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021