PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA

Pu Yi as a baby Xuantong, better known by his personal name of Henry Puyi, was the last emperor of China. At age three, Puyi took the throne after the death of his uncle Guangxu in November 1908. The death of Guangxu, many believe, was engineered by Empress Dowager Cixi. By this time the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty had been in a long decline. Puyi was the son of an imperial prince and the daughter of Jung Lu (the general who Cixi reportedly was engaged to when she was young and who supported her throughout her career).

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “ One of the more reviled figures of Chinese history, Puyi was elevated to the throne as a 2-year-old and abdicated at age 6, only to be reinstalled as a puppet of the Japanese occupation during World War II. In adult life, Puyi was a complicated and difficult person. Widely believed to be homosexual, he had a series of unhappy marriages. Having been surrounded by fawning eunuchs and servants most of his early life in the Forbidden City, he couldn't perform simple tasks for himself. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 28, 2012]

Malcolm Moore wrote in The Telegraph, “Plucked from his home as a toddler and declared a living god, Puyi was taken wailing and screaming to the Forbidden City to continue more than 2,000 years of imperial rule, aged just two years and 10 months. Puyi, whose life was featured in the film The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci, is still a figure of public fascination in China. "He was unique," said Mr Jia. "He lived through three dynasties. The entire tumult of China's last century can be summed up in him. He went from emperor to gardener, and in his last years he hung a picture of himself with Chairman Mao on his bedstead." Indeed the key moments of Puyi's life strike a familiar chord even today, making some of the details of his biography still too sensitive to be published in China. [Source: Malcolm Moore, The Telegraph, May 19, 2013 ^^]

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu; Forbidden City: FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com/china; Wikipedia; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites World Heritage Site ; Empress Dowager Cixi: Court Life During the Time of Empress Dowager Cixi etext.virginia.edu; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com : EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Last Manchu: The Autobiography of Henry Pu Yi, Last Emperor of China” by Paul Kramer, Henry Pu Yi, et al. Amazon.com; “My Husband Puyi: The Last Emperor of China” by Qingxiang Wang Amazon.com; Film: “Last Emperor” directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. Amazon.com . “Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com; “China Under the Empress Dowager” by E. Backhouse and J.O. Bland Amazon.com; “The Dragon Empress” by Marina Warner Amazon.com

China at the Time of the Empress Dowager Cixi and Last Emperor

Empress Dowager

Until 1850 or so, most Chinese believed the world was flat. "By the end of the 19th century the pressure from the world of ideas," wrote Yale history professor Jonathan Spence in Time magazine, "had led to strident and insistent demands for new structures of justice, new realms of freedom of aesthetic endeavor and the dissemination of information, and abandonment of autocracy for either a genuinely circumscribed constitutional monarchy or popularly passed republican form of government."

In late imperial times the agricultural land in the north was worked by people who owned the land while the land in the south was owned by landlords who didn’t work the land themselves. Peasants who worked the land in the south either paid a fixed rent in crops or a fixed rent in cash or paid their landlords with a share of their harvest. It was more of commercial operation than a feudal one. In the north peasants paid high agricultural taxes that were not abolished until 2006.

The threat presented by colonialism and Western power, forced the Chinese to take a hard look at themselves and re-evaluate their system of beliefs. In many cases traditional ideas about Confucianism, the Mandate of Heaven and authority were tossed out and Western ideas of capitalism, modernism, militarism and ultimately socialism and Marxism were embraced.

Early Life of Puyi

Puyi (Pu Yi) was born in 1906 and was named emperor just before his third birthday. The ultimate spoiled child, he had no set meal times. He simply issued the command: “Transmit the viands”---and he was given an Imperial banquet at that moment. He also was like an ordinary kid. He was given a bicycle by his Scottish tutor and arguably treasured it more than anything else he owned. He liked to ride it around the Forbidden City courtyards and is said to have removed doorstops in the Forbidden City so that he could cycle around.

The Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin Hall, on the western side of the Inner Palace within the Forbidden City) is where the child Emperor Puyi lived with his mother and the Dowager Empress Cixi. During state affairs Puyi sat on a throne in front of his audience. Behind him was a screen that hid another throne where Cixi once sat and told the child emperors before Puyi what to do.

Emperor Puyi was forced to abdicate by the forces that would create the Republic of China in 1911 when he was six years old, three years after he took the throne, during a nationalist uprising, thus ending the Qing dynasty’s 265 year hold on power. Afterwards Manchu headgear, and anything else related to the Qings, was banned. In Hong Kong people celebrated wildly in the streets and radicals attacked the Chinese newspaper and bank, forcing them to remove Manchu imperial flags.

Plot to Topple Puyi

Malcolm Moore wrote in The Telegraph, “In 1912, as China boiled with revolution, his own adoptive mother, the Empress Dowager Longyu, signed abdication papers forcing him from the Dragon Throne. Ever since, students of the end of the imperial dynasty have puzzled over why she appeared so willing to do so. Now Jia Yinghua, a 60-year-old historian and former government official, has discovered the answer: she was bribed with 20,000 taels, or 1700lb, of silver, and warned she might end up being beheaded if she refused. "What happened is so sensitive it has taken more than 100 years before it can be revealed," said Mr Jia, who assembled his latest work, The Extraordinary Life of the Last Emperor, from the secret archives at Zhongnanhai, the Chinese leadership compound, and from interviews with relations of the imperial courtiers. [Source: Malcolm Moore, The Telegraph, May 19, 2013 ^^]

"The time of his abdication was a time of corrupting and buying government officials," said Mr Jia. The imperial court in the last days of the Qing dynasty was a shadow of its former self. Foreign countries, particularly Britain, had humbled the Qing in battle, carved out rich territories and extracted huge payments. Starved of income, the Qing court had even pawned the lavish silk robes of Puyi's predecessor, the Guangxu emperor, said Mr Jia. ^^

Outside the Forbidden City, uprisings were sweeping the land as citizens called for a republic. In order to stabilise the situation, the court appointed Yuan Shikai, a general with influence over a powerful northern army, to be prime minister. But according to Mr Jia, Mr Yuan was determined to remove the last emperor from power, by turns cajoling, threatening and then bribing key figures at court. Not only did he bribe Puyi's adoptive mother, but he also corrupted her closest eunuch, Xiao Dezheng, and Prince Yikuang, one of the most powerful men at court, said Mr Jia. "In 1911, The Times reported that Prince Yikuang had two million silver dollars in his Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank account," said Mr Jia. "That was the result of bribes to remove the monarch." ^^

“The eunuch, meanwhile, received a similar sum, equivalent to more than £1 billion in today's money. He used it to build a house in Tianjin stuffed with treasures looted from the palace. In return, the eunuch told the Dowager Empress that she would be rich if she signed the abdication papers. "And if she refused, she would end up like Louis XVI during the French Revolution: beheaded," said Mr Jia. Mr Yuan did not stop there. He put pressure on the court by masterminding a series of threatening letters. ^^

"He had a good relationship with the Russian embassy and he asked them to write a letter saying if you do not sign the papers, the Western powers would force it through anyway," said Mr Jia, citing the archives at Zhongnanhai. Mr Yuan also secretly authored a telegram from 44 army commanders calling for the empire to dissolve, according to the notes of his aide, Zeng Yujun. After abdicating, Puyi was forced to leave the Forbidden City and briefly became a puppet ruler for the Japanese in a corner of North East China that they had conquered.” ^^

Puyi After His Abdication

Puyi lived in the Forbidden City until he was 18. He took the name of Henry, spent much of his time watching Harold Lloyd movies and hanging out in the palace gardens. He was served by 1000 eunuchs, 100 doctors and 200 chefs. During his last years in the Forbidden Palace, he and his large retinue supported themselves by selling of works of art. Some of Puyi's most trusted advisors and courtiers sold rare items from the imperial collection and replaced them with counterfeits.

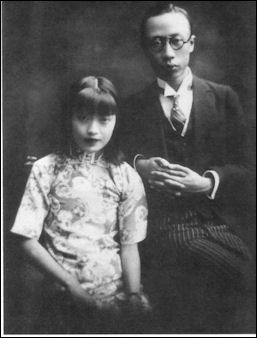

Pu Yi and Wanrong

Tristan Shaw of Listverse wrote: “In October 1911, a democratic revolution broke out, and Puyi abdicated only a few months later as part of the peace negotiations. After more than 2,000 years as a monarchy, China was now a republic.Although he was now powerless, Puyi was allowed to keep his title as the Xuantong emperor, and the new republican government also let him live in his old palace in Beijing with an annual allowance. Aside from a 12-day restoration of the monarchy in 1917, Puyi’s life was pretty uneventful until he was forced to relocate to the city of Tianjin in 1924. During that time, Tianjin was divided up into a variety of different foreign concessions and Puyi stayed in the Japanese part of the city until 1931. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse May 16, 2016]

In June 1917, the Warlord Zhang Xun brought his troops into Beijing and together with Kang Youwei supported Puyi’s accession to the throne. A few days later Zhang Xun was driven out of Beijing.

In 1924, 12 years after his abdication, an 18-year-old Puyi was ordered out of the Imperial Palace in Beijing by the provisional Kuomintang government. He took his elaborate court retinue, some 2,000 eunuchs and the imperial art collection with him to Tianjin, where he was exiled. It was the first time he left the Forbidden City.

Puyi wrote in his autobiography that he was eating an apple at 9:00am on November 5, 1924 when republican troops gave him three hours to vacate the Forbidden City That afternoon he signed a declaration that “the imperial title of the Hsuan Tung Emperor of the Great China is this day abolished in perpetuity” and the left the palace in a fleet of limousines.

Puyi's Private Life

According to the book Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Emperor's Final Marriage by Jia Yinghua, Puyi was a closet homosexual who had a relationship with a boy eunuch with "red lips and white teeth," and was given hormone shots to cure his impotence. According to the eunuch Sun Yaoting Puyi himself was less interested in his wife than he was in an attractive eunuch who “looked like a pretty girl with his tall, slim figure, handsome face and creamy skin.” Sun said Puyi and the eunuch were “inseparable as body and shadow.”

At the age of 16 he married Wanrong, a Manchu noble who was also only a teenager. She married him for his money and found he had none.Wanrong became addicted to opium and gave birth to a child fathered by a different man. Puyi’s last wife, Li Shuxian, was a former dance hall hostess who had been married two times before.

Puyi Under the Japanese and Russians

Puyi-Manchukuo

When the Japanese formed the puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria, Puyi was set up as the "Puppet Emperor" and lived in the Manchurian city of Changsun for 14 years. When the Japanese state collapsed after World War II, Henry was arrested as a war criminal by the Russians.

Tristan Shaw of Listverse wrote: “By 1932, the Japanese were in control of Manchuria, the ethnic Manchu Puyi’s ancestral homeland. The Japanese invited Puyi to assist as “chief executive” of the puppet state they established there, now known as Manchukuo. After two years in power, Puyi was made emperor of Manchukuo, a move which enraged his former Chinese subjects.” [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse May 16, 2016]

"Once World War II was over, the Soviets abducted Puyi and held him as a prisoner in the USSR for five years. Puyi was terrified to go back to China because he was considered a war criminal for helping the Japanese, but the Soviet authorities denied his request to stay in the country for good.”

Puyi spent five years against his will in Russia after World War II. After the communist victory in 1949, Puyi was charged with crimes related to his collaboration with the Japanese.

Puyi Returns to China

Pu Yi with a Soviet military officer

On his return to China in 1950 Pu Yi was sent to a labor camp, where he learned gardening and made peace with the Communist government by turning over three priceless imperial seals. He spent almost a decade in detention. After that Puyi was treated cordially by Chairman Mao and was eventually allowed to live out his days in Beijing,The Communists allowed him to work for the government as an editor and as a gardener in the Beijing Botanical Gardens at the University of Beijing.

"The most memorable day of my life," he told a Western journalist was December 4, 1959, when, after ten years of "re-education," he received a special pardon from the People's Republic. During his re-education he said he experienced "revelation and rebirth" and came to understand "how thoroughly soaked in crime and evil" the first half of his life had been. His job at the botanical garden in Beijing that paid a decent salary

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “ To Puyi’s relatives he “was a gentle, if somewhat befuddled man. He couldn't keep track of his money or figure out how to take the bus, but he was a lot of fun when he'd roll around with the children, playing, tickling and laughing. "He was just like one of the kids," said retired painter Zheng Shuang, 76, recalling her uncle. In fact, dajiu, or big uncle, as they called him, was so unpretentious that Zheng's younger brother wouldn't believe it when she told him, "Did you know that big uncle was the last emperor of China?" [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 28, 2012]

Zheng, his niece, recalled that Puyi once tried to take a bus, but being chivalrous, let all the women get on first. One of them was the conductor, and the bus left without him. Another time, she went with him to a shop near the botanical garden and realized he had never used money. "My uncle was trying to buy something and he didn't know which notes to use. He dropped the money all over the floor," said Zheng. "Being emperor is very sad. You lost the chance to live an ordinary life."

Puyi's Last Years and Death

Pu Yi and Mao

Puyi spent his last few working quietly working as a gardener and released a ghostwritten autobiography. The last year of Puyi's life coincided with the start of the Cultural Revolution, Mao's violent purge of the elites. Although the Communist Party went out of its way to protect Puyi and family members, the last emperor was receiving threatening letters and became frightened and checked himself into a hospital. "I think he was literally frightened to death," said Jia. [Ibid]

Puyi died in 1967, from complications of kidney cancer and heart disease, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. His ashes were eventually buried in a large modern tomb, 100 miles southwest of Beijing, near the tombs of four Qing Emperors (including his predecessor Guangxu), and the bass player from the rock band Tang Dynasty, who died in a car accident in 1995.

Puyi’s brother-in-law, Ran Qi, Guo Luo, a consultant for the Bertolucci film, who was living in apartment in the Forbidden City a the age of 96 in 2008, told Smithsonian magazine, “Puyi never wanted to be emperor. His great wish was to go to England and study to become a teacher.”

Last Emperor's Relatives

Puyi died in 1967 in relative obscurity. Although he had no children, he is survived by a number of nieces, nephews and cousins. In 2012, relatives of Puyi gathered at the Beijing mansion where he was born and shared their memories of him. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “In a rare reunion of one of China's most famous families, four relatives of the late Emperor Puyi convened at the willow-fringed lakefront mansion in Beijing where he was born. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 28, 2012]

"There's considerable curiosity in China about those remaining royal family members, but their existence does not carry the same cachet as elsewhere, perhaps because of decades of anti-imperialist indoctrination by communists. The relatives hardly ever get together, and even less often in public “ royal blood being something you don't advertise in a communist country “ but made an exception to mark the publication of a new series of books about their family.

Pu Yi on the cover of Time with Stalin, Hirohito and Chiang Kai-shek

"They did not appear glamorous, the women wearing sensible old-lady shoes and large eyeglasses. Though the mansion was their playground as children, they looked ill at ease in a sitting room adorned with yellow-tasseled lanterns and heavy curtains in the same shade of imperial yellow. "I remember this place being much larger. As I child, I would get lost going in circles around the grounds," said Puyi's cousin Jin Aiyao, 78, a retired academic, looking around in confusion as she tried to reconcile her memories.

"After the communist victory in 1949, the government confiscated the mansion from Prince Chun, Puyi's father. His relatives dropped their Manchurian names and joined the Communist Party. Guo Manruo, a 67-year-old niece, recalled going out of her way to choose a penniless husband descended from three generations of farmers. She was proud that her new family didn't have much to eat and lived in a small, dark apartment. "I wanted to prove that I was part of the new red China, not of the imperial China," Guo said. "I was honored that my husband's family was poor."

"Nevertheless, the former imperial relatives enjoyed privileges. Chairman Mao Tse-tung and Premier Zhou Enlai checked in on them frequently. Guo remembered that during the famine of the 1950s, Zhou sent her a large ham, a delicacy she'd never tasted before. The relatives were encouraged to visit Puyi in prison; "Mao wanted to show his status, that he was above them by being generous. The family was always treated as special,"' said Jia Yinghua, a Beijing historian whose four books about the family were being launched at Thursday's event at the mansion, now a public museum.

"Na Genzheng, a relative of the late Empress Dowager Cixi and a historian specializing in Manchurian themes, said that although his family became very poor after the communist takeover, he remembers that for his sister's wedding, his mother gave her a traditional Chinese dress and tucked into it a small portrait of the empress. That was the kind of memorabilia the family had lying around.

The relatives' memories of Puyi include fond ones, especially his playfulness with children. But as a whole, they say they're not proud of having him as a relative --- or of having royal blood. "It is a secret. I don't tell people I'm related to the last emperor," said Guo, who almost chose not to attend Thursday's event. "That's why I didn't want to come here today. I just wanted to be a regular person."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Pu yi website

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021