BOXER REBELLION

The Boxer Rebellion was a violent uprising in 1899–1901 against foreigners by a group of Chinese that wanted to rid China of foreigners and foreign influences. It occurred after China's humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the partitioning of much of the east coast of China among the United States, Japan, Britain, France, Russia and Germany through trade concessions. This resulted in resentment towards foreigners among ordinary Chinese. The movement was supported by the Qing (Manchu) court — the rulers of imperial China at that time — even though it initially was condemned for being weak against foreigners. The Boxer Rebellion hastened the end of the Qing Dynasty.

The Boxer Rebellion was a violent uprising in 1899–1901 against foreigners by a group of Chinese that wanted to rid China of foreigners and foreign influences. It occurred after China's humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the partitioning of much of the east coast of China among the United States, Japan, Britain, France, Russia and Germany through trade concessions. This resulted in resentment towards foreigners among ordinary Chinese. The movement was supported by the Qing (Manchu) court — the rulers of imperial China at that time — even though it initially was condemned for being weak against foreigners. The Boxer Rebellion hastened the end of the Qing Dynasty.

In 1900, Chinese insurgents known as the Righteous Fists of Harmony (and dubbed the Boxers by foreigners) rose against both the Qing dynasty and Western influences. Christian missionaries and Chinese Christians were slain, as were foreign diplomats and their families. To blunt the Boxers’ threat to the dynasty, Cixi sided with them against the Westerners. But troops sent by a coalition of eight nations, including England, Japan, France and the United States, put down the Boxer rebellion in a matter of months. [Source: Owen Edwards, Smithsonian magazine, October 2011]

The Chinese also resented Western technologies such as railroads, steamboats and telegraph lines putting Chinese out of work. Westerns were blamed for all kinds of tragedies — droughts, plagues and floods — and accused of stealing babies and filling ships with cargoes of "eyes and female nipples" bound for Western medicine cabinets. Many Chinese also believed that priests smeared themselves with menstrual blood, nailed naked women and fetuses to the Christian cross, and made flags from the pubic hair of 10,000 women.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a professor of history at the University of California Irvine and author of “China in the 21st Century said he believes the Boxer Rebellion is a much misunderstood period of Chinese history. He told the China Daily it is still best-known in the West from the 1963 Charlton Heston film, “55 Days at Beijing.” “"The thing about the Boxer Rebellion was that they didn't really box and they weren't really rebels. They were loyalists and they used martial arts. They supported the dynasty and the dynasty decided to use them."

Boxer Rebellion National Archives archives.gov/publications ; Modern History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall ; San Francisco 1900 newspaper article Library of Congress ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Cox Rebellion PhotosCaldwell Kvaran ; Eyewitness Account fordham.edu/halsall ; Book: "The Boxer Rebellion" by Diana Preston.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; FOREIGNERS AND CHINESE IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES factsanddetails.com; TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com; EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Boxer Rebellion" by Diana Preston. Amazon.com; “The Siege at Peking” by Peter Fleming, David Shaw-Parker Amazon.com; “Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China” by Jung Chang Amazon.com

Boxers

The Boxer Rebellion was named after the Boxers, a 40,000-member secret organization actually called the "Righteousness and Harmony Society." Violently anti-western, they were called Boxers because they engaged in martial art rituals and the Chinese word for "society" sounded like the English word "fist." The future American president Herbert Hoover was in Beijing at the time of the Boxers Rebellion. Of the Boxers he wrote, "Their avowed purpose was to expel all foreigners from China, to root out every foreign thing — houses, railways, telegraphs, mines — and they included all Christian Chinese and all Chinese who had been associated with foreign things."

The Boxer Rebellion was named after the Boxers, a 40,000-member secret organization actually called the "Righteousness and Harmony Society." Violently anti-western, they were called Boxers because they engaged in martial art rituals and the Chinese word for "society" sounded like the English word "fist." The future American president Herbert Hoover was in Beijing at the time of the Boxers Rebellion. Of the Boxers he wrote, "Their avowed purpose was to expel all foreigners from China, to root out every foreign thing — houses, railways, telegraphs, mines — and they included all Christian Chinese and all Chinese who had been associated with foreign things."

The Boxers wore turbans and red sashes and believed themselves to be to invulnerable to bullets fired from foreign weapons. The Boxers formed to overthrow both the foreigners and the Qing. Before the Boxer Rebellion they perpetrated isolated attacks and murders mostly against "foreign-tainted" Chinese. The Qing, recognizing their compromised position, united with the Boxers to attack the Western presence in the country.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Desperate for some way to avenge herself against the “foreign devils,” Western and Japanese, who were tormenting China, the Empress Dowager called for help to a group of mystical warriors, known as the Boxers. The Boxers were skilled in the arts of war, and because they possessed certain magical arts of latter-day Daoism, they were invulnerable to bullets or other weapons. This feature, and their fanatical hatred of foreigners, led the Empress Dowager secretly to summon them to Beijing to drive the foreign legations out of Northern China and restore China’s glory. When the government’s plan became evident, Wang Yirong rushed to the palace and waited until he had a chance to plead with the Empress Dowager to adopt saner tactics, but his words were wasted. It turned out that in the Boxer creed, the part about invulnerability to bullets was mistaken. As the Boxers were being mown down like grass in the streets of Beijing, the Empress Dowager hastily departed on a long-delayed tour of China’s western provinces. In shame and frustration at this macabre outcome, Wang Yirong took his own life. /+[Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Background of the Boxer Rebellion

At the end of the 19th century China existed as a nation in name only. The Qing dynasty controlled only parts of China and the rest of China was divided among warlords and foreigners who controlled different parts of the country. As the Qing dynasty fell apart more and more of China was wrestled from its control. The Qing dynasty was weakened by the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “China had lost the war with Japan because she was entirely without modern armament. While Japan went to work at once with all her energy to emulate Western industrialization, the ruling class in China had shown a marked repugnance to any modernization; and the centre of this conservatism was the dowager empress Cixi. She was a woman of strong personality. She felt instinctively that Europeanization would wreck the foundations of the power of the Manchus and the gentry, and would bring another class, the middle class and the merchants, into power. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“There were reasonable men, however, who had seen the necessity of reform—especially Li Hongzhang, who has already been mentioned. In 1896 he went on a mission to Moscow, and then toured Europe. The reformers were, however, divided into two groups. One group advocated the acquisition of a certain amount of technical knowledge from abroad and its introduction by slow reforms, without altering the social structure of the state or the composition of the government. The others held that the state needed fundamental changes, and that superficial loans from Europe were not enough. The failure in the war with Japan made the general desire for reform more and more insistent not only in the country but in Beijing. Until now Japan had been despised as a barbarian state; now Japan had won! The Europeans had been despised; now they were all cutting bits out of China for themselves, extracting from the government one privilege after another, and quite openly dividing China into "spheres of interest", obviously as the prelude to annexation of the whole country.

“In Europe at that time the question was being discussed over and over again, why Japan had so quickly succeeded in making herself a modern power, and why China was not succeeding in doing so; the Japanese were praised for their capacity and the Chinese blamed for their lassitude. Both in Europe and in Chinese circles it was overlooked that there were fundamental differences in the social structures of the two countries. The basis of the modern capitalist states of the West is the middle class. Japan had for centuries had a middle class (the merchants) that had entered into a symbiosis with the feudal lords. For the middle class the transition to modern capitalism, and for the feudal lords the way to Western imperialism, was easy. In China there was only a weak middle class, vegetating under the dominance of the gentry; the middle class had still to gain the strength to liberate itself before it could become the support for a capitalistic state. And the gentry were still strong enough to maintain their dominance and so to prevent a radical reconstruction; all they would agree to were a few reforms from which they might hope to secure an increase of power for their own ends.

Empress Dowager Cixi and the Boxer Rebellion

Cixi's biggest mistake was to encourage the disastrous Boxer rebellion, a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian movement that culminated in a bloody siege of the foreign legations in Beijing. The Empress Dowager supported the rebellion and at one point declared war against the United States, Japan and seven European countries. In her book “The Boxer Rebellion”, Diana Preston wrote of the Empress Dowager: "On the one hand she was afraid of the Boxers because they threatened her rule. She couldn't control them. On the other hand, they represented a growing and highly motivated army she didn't have to pay, one that might help her 'purify' China of its corrupting foreign influences." Her own troops finally joined the Boxers.

Many historians believe that Cixi’s support of the Boxers was prompted by plans by Emperor Guangxu to implement serious reforms. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “When the empress Cixi saw that the emperor was actually thinking about reforms, she went to work with lightning speed. Very soon the reformers had to flee; those who failed to make good their escape were arrested and executed. The emperor was made a prisoner in a palace near Beijing, and remained a captive until his death; the empress resumed her regency on his behalf. The period of reforms lasted only for a few months of 1898. A leading part in the extermination of the reformers was played by troops from Gansu under the command of a Muslim, Tung Fu-Xiang. General Yuan Shikai, who was then stationed at Tientsin in command of 7,000 troops with modern equipment, the only ones in China, could have removed the empress and protected the reformers; but he was already pursuing a personal policy, and thought it safer to give the reformers no help. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“There now began, from 1898, a thoroughly reactionary rule of the dowager empress. But China's general situation permitted no breathing-space. In 1900 came the so-called Boxer Rebellion, a new popular movement against the gentry and the Manchus similar to the many that had preceded it. The Beijing government succeeded, however, in negotiations that brought the movement into the service of the government and directed it against the foreigners. This removed the danger to the government and at the same time helped it against the hated foreigners. But incidents resulted which the Beijing government had not anticipated. An international army was sent to China, and marched from Tientsin against Beijing, to liberate the besieged European legations and to punish the government.

Boxers Rebellion Violence

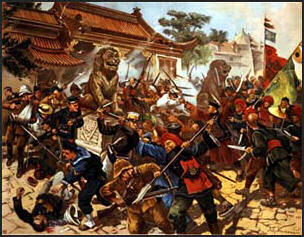

In 1900 the Boxers stormed the foreign settlements in Beijing and quickly laid siege to the lightly armed diplomatic compounds. The trapped diplomats quickly sent out word of their plight, and before many days had passed Western troops arrived in Beijing.

In 1900 the Boxers stormed the foreign settlements in Beijing and quickly laid siege to the lightly armed diplomatic compounds. The trapped diplomats quickly sent out word of their plight, and before many days had passed Western troops arrived in Beijing.

The Boxers besieged foreign neighborhoods, attacked foreign soldiers and killed a handful of foreign residents while chanting:

”Burn, burn, burn, kill, kill, kill...

Surely government bannermen are many;

Certainly foreign soldiers a horde;

But if each of people spits once

They will drown bannermen and invaders together”

[Source: Poems of Revolt, 1962]

One of the worst episodes took place on June 13, when the Boxers set fire to a mission compound occupied by 200 Chinese Christian converts. "Between sword and flames,” the North China Daily News reported, "the whole lot of those unfortunate converts were either ruthlessly slain or burned to cinders." Some of the Chinese converts were tortured and decapitated: their heads and entrails displayed to besieged foreigners.

Foreigners Besieged by the Boxers

The primary event of the Boxer Rebellion was a siege by a force of 25,000 Boxers against 4,000 people from 18 nations holed up in Tientsin, a foreign settlement in Beijing, protected by 1,700 Russian soldiers and 1,100 sailors and marines from several countries.

The siege lasted for two months. The besieged Europeans quickly ran out food but not alcohol. Trying to make the best of the situation they continued to dress for dinner and indulge themselves in the plentiful supplies of champagne while they ate mule shoulder stew.

Describing the measures taken to defend themselves, Hoover wrote, "In hunting for materials for barricades we hit upon the great godowns [warehouses] filled with sacked sugar, peanuts, rice and other grain. Soon we and other foreigners whom I enlisted and a thousand terrified Christian Chinese were carrying and piling up walls of sacked grain and sugar along the exposed sides of the town and at cross streets."

Assaults on the barricades by Boxers, accompanied by a 250,000-person mob and 80,000 Chinese troops, were repulsed by marines and sailors. Exaggerated reported that Boxers were torturing and beheading foreigners found their way to the foreign press. One described a professor who was tortured for three days and decapitated and his head was displayed on a spike. Some people inside in Tientsin were discussing how they would shoot their wives and children if the Boxers got too close. But in the end few foreigners were killed or hurt

End of the Boxers Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion was crushed by the intervention of British, French, German, American, Russian, and Japanese troops. A multinational force of 20,000 troops — made up mainly of soldiers from Britain the United States, Russia, France and Japan — was dispatched from the coast of China to Beijing. The assemblage of force showed unusual cooperation considering that all the nations involved were global rivals at the time.

The multinational army arrived after 55 days and quickly put down the rebellion. Describing the arrival of the first Western forces, Hoover wrote, "We saw them coming over the plain. They were American and Welsh Fusilers. I do not remember a more satisfying musical performance than the bugles of the American marines entering the settlement."

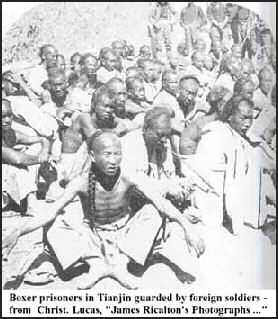

The Boxers were driven off into the plains around Tientsin and many were rounded up. Thousands were machine-gunned down at the Pai River. Further north Russian troops drowned thousands of Chinese in the Amur River. According to one account 247 missionaries, 66 diplomatic personnel and 30,000 Chinese Christians were killed in the rebellion but these figures are considered wildly exaggerated.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote: A consortium of foreign troops marching under eight different flags stormed into North China and lifted the siege. The invaders then launched a series of brutal campaigns of retribution, during which European, Russian, American, Indian, and Japanese soldiers killed many Chinese who had never been Boxers at all, or even supporters of the insurrection. The victims included a significant number of ethnic Manchus. Just as memories of Boxer violence have cast a long and disturbing shadow over Western views of China, stories about what Eight Allied Armies did in Asia have cast a long and disturbing shadow over Chinese views of the West and Japan.” [Source: Jeffrey Wasserstrom,, professor of history at the University of California, Irvine:, Asian American Writers' Workshop, February 4, 2014]

Empress Dowager Cixi During the Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion the Empress Dowager fled from the Forbidden City in Beijing for Xian with her court. She and the Emperor managed to slip out of the city disguised as peasants. Even though the Qing Dynasty was in ruins, foreigners kept it propped because they viewed a Qing dynasty under their control better than a potentially hostile newcomer and they saw no better alternative.

According to a famous story, after the Boxer Rebellion, when Empress Cixi was worried that European troops were going to attack the Forbidden City, she summoned Emperor Guangxu and his favorite concubine Zhen Fei and then ordered the palace evacuated. Zhen Fei begged for the Emperor to stay behind and negotiate with the Europeans. Cixi, the story goes, was enraged by the “Pearl Concubine’s” audacity and ordered some eunuchs to throw her down a well at the Forbidden City.

There is no evidence to support this story. Cixi’s great, great nephew told Smithsonian magazine. “The concubine was sharp-tongued and often stood up to Cixi, making her angry. When they were about to flee the foreign troops, the concubine said she’d remain within the Forbidden City. Cixi told her that the barbarians world rape here if she stayed, and that it was best if she escaped disgrace by throwing herself down the well. The concubine did just that.” The well is popular stop at the Forbidden City and is so small that neither story seems likely.

See Separate Article CHINA UNDER THE EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI factsanddetails.com

After the Boxer Rebellion

After the rebellion, China was forced to pay $330 million in reparations; Western armies occupied and plundered Beijing; and the Qing dynasty was forced to accept foreign armies posted in China. The United States Open Door Policy (1899) led to the American involvement in the Boxer Rebellion and other incidents around the globe and helped establish the United States as a world power. Shock waves caused by the rebellion and by the reparations demanded by the outraged world powers sent military and political convulsions through China for the rest of the 20th century.

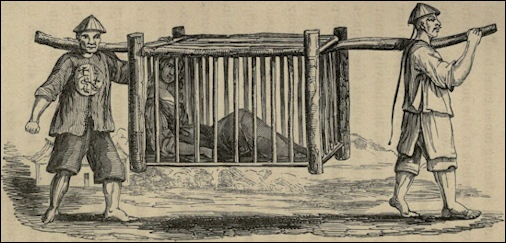

Cage with Mrs Noble

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: After the Europeans captured Beijing in 1900, the dowager empress and her prisoner, the emperor, had to flee; some of the palaces were looted. The peace treaty that followed exacted further concessions from China to the Europeans and enormous war indemnities, the payment of which continued into the 1940's, though most of the states placed the money at China's disposal for educational purposes. When in 1902 the dowager empress returned to Beijing and put the emperor back into his palace-prison, she was forced by what had happened to realize that at all events a certain measure of reform was necessary. The reforms, however, which she decreed, mainly in 1904, were very modest and were never fully carried out. They were only intended to make an impression on the outer world and to appease the continually growing body of supporters of the reform party, especially numerous in South China. The south remained, nevertheless, a focus of hostility to the Manchus. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Cixi survived the Boxer Rebellion , but with a reputation for cruelty and treachery. She needed help dealing with the foreigners clamoring for greater access to her court. So her advisers called in Lady Yugeng, the half-American wife of a Chinese diplomat, and her daughters, Deling and Rongling, to familiarize Cixi with Western ways.

Imperial Reform Edict Issues After the Boxer Rebellion See Reform Imperial Edict of 1901 (Issued by the Empress Dowager Cixi, 1835-1908) Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government (January 29, 1901) [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Image Sources: Boxer Rebellion, Ohio State University Columbia University, Nolls website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021