TAIPING REBELLION

Taiping Revolution Seal

The Taiping rebellion was the world's bloodiest civil war. Lasting for 13 years from 1851 to 1864, it nearly toppled the Qing Dynasty and resulted in the death of 20 million people — more than the entire population of England at that time. The conflict began as an uprising and a rebellion but became ‘simply a descent into anarchy.” It is also viewed by many historians as a precursor to the Long March and the Cultural Revolution.

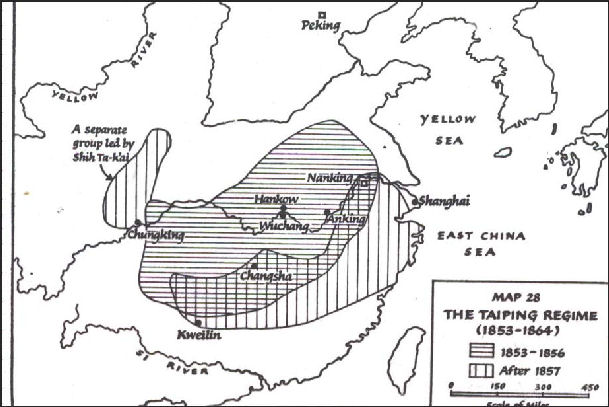

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In the 1840s a young man from Guangdong named Hong Xiuquan (1813-1864) created his own version of Christianity and made converts in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. Hong believed that he was the Younger Brother of Jesus and that his mission, and that of his followers, was to cleanse China of the Manchus and others who stood in their way and “return” the Chinese people to the worship of the Biblical God. Led by Hong, the “Godworshippers” in rural Guangxi rose in rebellion in 1856 in hopes of creating a new “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace” (Taiping Tianguo). Their movement is known in English as the Taiping movement (“taiping” meaning “great peace” in Chinese). The rebels swept through southern China and up to the Yangzi River, and then down the Yangzi to Nanjing, where they made their capital. Attempts to take northern China were unsuccessful, and the Taiping were eventually crushed in 1864. By that time, the Taiping Rebellion had caused devastation ranging over sixteen provinces with tremendous loss of life and the destruction of more than 600 cities. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: For almost 14 years, two forces skirmished and battled and laid siege to each other’s fortresses and cities, with most of the fighting along the country’s longest river, the Yangtze, China’s ‘serpent.” “The glow of the fires illuminates the sky,” exclaimed one Chinese observer near Shanghai in the spring of 1860, “and the cries of the people shake the earth.” As Platt observes, the conflict ended not by surrender but through annihilation. [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, March 30, 2012, Gordon G. Chang is a columnist at Forbes.com and the author of “The Coming Collapse of China.”]

See Separate Article LEADERS OF THE TAIPING REBELLION AND THE IDEOLOGY BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com ; Taiping Rebellion: Taiping Rebellion.com taipingrebellion.com ; Wikipedia Taiping Rebellion article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War" by Stephen R. Platt Amazon.com; "God's Chinese Son" by Yale's Jonathan Spence, about the Taiping Rebellion Amazon.com; “The Taiping Rebellion 1851–66" (Men-at-Arms) by Ian Heath and Michael Perry Amazon.com; “The World of a Tiny Insect: A Memoir of the Taiping Rebellion and Its Aftermath” by Zhang Daye and Xiaofei Tian Amazon.com; “The Taiping Rebellion - History and Documents Volume 1" by Franz Michael, Chung-li Chang Amazon.com

Significance of the Taiping Rebellion

What was so remarkable, and so troubling, about the Taiping Rebellion was that it spread with such swiftness and spontaneity. It did not depend on years of preliminary “revolutionary” groundwork (as did the revolution that toppled the monarchy in 1912 or the 1949 revolution that brought the Communists to power). And while Hong’s religious followers formed its core, once the sect broke out of its imperial cordon and marched north, it swept up hundreds of thousands of other peasants along the way “ multitudes who had their own separate miseries and grievances and saw nothing to lose by joining the revolt. Out-of-work miners, poor farmers, criminal gangs and all manner of other malcontents folded into the larger army, which by 1853 numbered half a million recruits and conscripts. The Taiping captured the city of Nanjing that year, massacred its entire Manchu population and held the city as their capital and base for 11 years until the civil war ended.

In the West “all romance was on the side of the Taiping rebels, who at the onset were heralded abroad as the liberators of the Chinese people. As one American missionary in Shanghai put it at the time, “Americans are too firmly attached to the principles on which their government was founded and has flourished to refuse sympathy for a heroic people battling against foreign thralldom.”

But..for all of the West’s contempt for China’s government in the 19th century, when the Taiping Rebellion actually drove it to the brink of destruction, it was Britain that intervened to keep it in power. Britain’s economy depended so heavily on the China market at the time (especially after the loss of the United States market to the American Civil War in 1861) that it simply could not bear the risk of what might come from a rebel victory. With American encouragement, the British supplied arms, gunships and military officers to the Manchu government and ultimately helped tip the balance of the war in its favor.

Hong Xiuquan

Hong Xiuquan

The Taiping sect was named after its leader, a deranged schoolteacher named Hong Xiuquan, who claimed he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ and the second son of God and referred to himself as T'ai-ping T'ien-Kuo ("Heavenly King of the Heavenly King of the Great Peace"). The cult's beliefs were forged by Hong from a blend of Protestant evangelism, Chinese philosophy, utopian thinking and Old Testament militancy. Some say that Hong suffered from disease-induced hallucinations. Even though he promoted the equality of women he kept 100 wives. The rebellion began to unravel when Hong had his loyal assistant Yang Hsiu Ch'ing assassinated and then ordered the execution of the assassin.

Hong was a wannabe scholar. Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “Originally, all Hong Xiuquan wanted was to be part of the establishment. A village schoolteacher, he immersed himself in Confucian scholarship for the civil service exam, but he just kept failing.

Takahiro Suzuki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “His brilliance was recognized while he was young and inspired great hope among his relatives. Hong took the highly competitive imperial examinations to become a bureaucrat multiple times but failed every time. After his fourth failure, he gave up on a bureaucratic career. This experience apparently fostered antigovernment feelings in the young man. [Source: Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 2014]

See Separate Article LEADERS OF THE TAIPING REBELLION AND THE IDEOLOGY BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com

China at the Time of the Taiping Rebellion

During the mid-nineteenth century, China's problems were compounded by natural calamities of unprecedented proportions, including droughts, famines, and floods. Government neglect of public works was in part responsible for this and other disasters, and the Qing administration did little to relieve the widespread misery caused by them. Economic tensions, military defeats at Western hands, and anti-Manchu sentiments all combined to produce widespread unrest, especially in the south. South China had been the last area to yield to the Qing conquerors and the first to be exposed to Western influence. It provided a likely setting for the largest uprising in modern Chinese history — the Taiping Rebellion. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Stephen R. Platt wrote in the New York Times, “The Taiping Rebellion exploded out of southern China during the early 1850s in a period marked, as now, by economic dislocation, corruption and a moral vacuum. Rural poverty abounded; local officials were wildly corrupt; the Beijing government was so distant as to barely seem to exist. The uprising was set off by bloody ethnic feuds between Cantonese-speaking Chinese and the minority Hakkas over land rights. Many Hakkas had joined a growing religious cult built around a visionary named Hong Xiuquan, who believed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ. When local Qing officials took the side of the Chinese farmers, they provoked the Hakkas “ and their religious sect “ to take up arms and turn against the government. [Source: Stephen R. Platt, New York Times, February 9, 2012. Platt is an associate professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the author of “Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War”]

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: China in the middle of the 19th century was in ferment. For one thing, the Manchus, once fierce warriors on horseback, had grown too used to the sedentary ways of the Chinese they had conquered. When Hong mounted his challenge, the young emperor, Xianfeng, was living a life of debauchery in the magnificent Summer Palace instead of working with his ministers in the center of the Chinese capital. [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, March 30, 2012]

" And for many Chinese, Xianfeng was also a hated foreigner, so it is not surprising that Hong Xiuquan’s fast-growing brand of Christianity soon turned political, in other words, anti-Manchu. As for China’s place in the world at that tome Platt wrote: “Europe had been through its own upheavals just five years earlier with the revolutions of 1848 and the events in China seemed a remarkable parallel: the downtrodden people of China, oppressed by their Manchu overlords, had, it seemed, risen up to demand satisfaction.”

Taiping Rebellion Followers

In 1843 Hong Xiuquan, Feng Yunshan and Hong Rengan founded the God Worshipping Society, a heterodox Christian sect, in Hua County (present-day Huadu District, Guangdong). The following year they traveled to Guangxi to spread their teachings to the peasant population. After that, Hong Xiuquan returned to Guangdong to write about his beliefs, while Feng Yunshan remained in the Mount Zijing area to rally people like Yang Xiuqing and Xiao Chaogui to join their sect. [Source: Wikipedia]

Takahiro Suzuki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Hong made the assertion that all people were equal in front of God, formed the God Worshipping Society and started preaching. Although he found few sympathetic ears in Guangdong Province, he succeeded in gathering believers in the areas around Jintian in what is now Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.[Source: Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 2014]

Jonathan Fenby describes Hong’s “religion” as "a strange mixture of Christianity and a primitive kind of communism". Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “The Europeans saw Hong's claim to be the brother of Christ as heresy, but he was not preaching for their benefit. He accompanied his spiritual message with a political one - a vision of equality and shared land ownership. This appealed to poor farmers, who were suffering from a sense of hopelessness, according to Guo Baogang of Dalton State college. "Peasants have a very miserable life in the middle of the 19th Century," he says. "There's a lot of famines and unemployment, most peasants have no land. So they're very vulnerable to the utopian thinkers prescribing a perfect society as a way to escape from the existing society." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, September 17, 2012 /]

“Hong and his disciples took to the road, selling writing brushes and ink and spreading the good news about the heavenly kingdom as they went. The movement grew fast in south-west China. "When people of this earth keep nothing for their private use, but give all things to God for all to use in common, then every place shall have equal shares, and everyone be clothed and fed," Hong declared. As in these earlier rebellions, many of those who joined Hong's Heavenly Army had nothing to lose. Population growth had deprived them of a stake in society. The Qing empire was a victim of its own success. "Once you have a long peace, you see the rapid growth of the population," says Guo Baogang. /

"When the Manchus came into China, the population was about 100 million. By the 19th Century, after 200 years of economic growth, the population increased to something around 400 million. But arable land, that figure was only about 30 percent growth. So that added all the social stress." The promise of land for all soon brought hundreds of thousands to Hong's banner. /

Social, Political and International Forces Behind the Taiping Rebellion

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: As an explanation for why the rebellion spread remarkably fast, Karl Marx, then writing for The New-York Daily Tribune, attributed the rebels’ quick advances to globalization, namely, Britain’s forcing the opening of China to trade after the First Opium War, which ended in 1842. Dissolution of the imperial order, Marx said, “must follow as surely as that of any mummy carefully preserved in a hermetically sealed coffin, whenever it is brought into contact with the open air.” [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, March 30, 2012]

Platt suggests that Marx was right and that the Taiping rebellion was aided by the links tying China to an international industrial economy. Qing China was not as closed as historians have made it appear, he notes. Globalization was already at work destabilizing the country. The British and French, for instance, were conducting military campaigns against the Qing to further open the empire to trade, and though they did not intend to support the Taiping, their actions in late 1860 “ at the height of the uprising “ nonetheless inspired the Chinese rebels. After all, the Europeans were able to force the young Manchu emperor from his capital, Peking, with a relatively small force.

Eventually, however, Britain threw its full support to the Qing, after deciding that the commercial advantage lay with them rather than with the rebel Taiping. In what is perhaps the most suggestive passage in his book, Platt persuasively argues that the civil war was an international affair because both sides were ‘so intractably balanced that the final outcome was to a large degree determined by the diplomatic and military interventions of outsiders in the early 1860s.”

Beginning of the Taiping Rebellion

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In 1848, native unrest began in the province of Hunan, as a result of the constantly growing pressure of the Chinese settlers on the native population; in the same year there was unrest farther south, in the province of Guangxi, this time in connection with the influence of the Europeans.

The rebellion began in the southern Chinese city of Suzhou and was carried out by a group of unassimilated northern residents, known as Hakkas, who were formed into the Taiping Sect, a disciplined army of 600,000 men and 500,000 women, who didn't drink, gamble or smoke. After clashing with imperial soldiers in July 1850, the Taiping sect conquered most of southern China in 1851, and marched north smashing Buddhist, Confucius and Taoist temples and idols as they went.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In 1850, Hong Xiuquan (Hung Hsiu-ch'üan) launched a rebellion against the Qing dynasty from the southern province of Guangxi. Bent on establishing what Hung termed the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace, the T'ai-p'ing Rebellion rapidly spread out of control, with the regular Green Standard and Banner forces unable to stabilize the situation. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Hong had a following in the thousands who were heavily anti-Manchu and antiestablishment . Hong's followers formed a military organization to protect against bandits and recruited troops not only among believers but also from among other armed peasant groups and secret societies. In 1851 Hong Xiuquan and others launched an uprising in Guizhou Province. Hong proclaimed the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace (Taiping Tianguo, or Taiping for short) with himself as king. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Rebelling against the Qing Dynasty and the decadence it spawned, the sect set up an independent, utopian society based on sexual equality and puritanical Christian values. In the territories it brought under control it abolished slavery, foot biding, polygamy and arranged marriages. The Taiping Rebellion spread into 16 of 18 of China's provinces. More than 600 walled cities were captured, including Nanking, which became the Taiping capital.

Jintian Uprising

The Jintian Uprising is regarded as the beginning of the Taiping Rebellion. It was an armed revolt formally declared by Hong Xiuquan on January 11, 1851. Named after Jintian (present-day Guiping, Guangxi), where it took place, it was the beginning of the Taiping Rebellion. Around 1849, a famine broke out in Guangxi and the Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth Society) rose in rebellion against the ruling Qing Dynasty. By the 7th lunar month of 1850, Hong Xiuquan had amassed over 20,000 followers, who were all gathered at Jintian. In preparation for an uprising, Hong organized these men into military formations, each led by commanders with military ranks: a marshal commanded five divisional marshals; each divisional marshal commanded five brigade marshals and so on down to each company leader who had four soldiers under him. As the Qing imperial army in Guangxi was lacking in strength, with only about 30,000 troops, and was occupied with suppressing the Tiandihui's rebellion, Hong Xiuquan and his followers were able to build their forces without being noticed by the government. [Source: Wikipedia]

Battle of Tongcheng

Reporting from Guiping,,Takahiro Suzuki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The town of Jintian looks out over a flatland with mountains to its rear, making it a strategically advantageous and highly defensible launching point for attacks. In 1851, Hong Xiuquan led a rebellion of peasants against the Qing dynasty in Jintian. He went on to establish a state called the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom there. His former command center was surrounded by earthworks two meters high and 220 meters long. According to Chen Yongxiang, deputy curator of a memorial hall at the Historic Site of Jintian Uprising of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom,, a large flag bearing the title Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was placed in front of the stone on the day of the revolt. When Hong exhorted his followers to rise up, the flag suddenly lifted and fluttered despite the lack of wind. His followers are said to have shouted, "Crush the Qing dynasty!" [Source: Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 2014 ]

Nanjing University Prof. Cui Zhiqing, an expert on the Taiping Rebellion described the social backdrop to Yomiuri Shimbun: "In the Guangxi district, farmland had not been expanded as the population increased, and as a result, there were a great many poor farmers and jobless people." In Jintian particularly, more than half of local farmland was owned by absentee landlords. These circumstances inspired many poor people to join his sect, which decreed the creation of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.

Advance of the Taipings

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom captured Nanjing and made it their capital, and controlled large parts of southern China. The rebels wanted to replace other religions with Christianity, and to keep sexes separate — even married couples. They also sought to end private land ownership and private trade

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: A large part of the officials, and particularly of the soldiers sent against the revolutionaries, were Manchus, and consequently the movement very soon became a nationalist movement, much as the popular movement at the end of the Mongol epoch had done. Hong made rapid progress; in 1852 he captured Hankow, and in 1853 Nanking, the important centre in the east. With clear political insight he made Nanking his capital. In this he returned to the old traditions of the beginning of the Ming epoch, no doubt expecting in this way to attract support from the eastern Chinese gentry, who had no liking for a capital far away in the north. He made a parade of adhesion to the ancient Chinese tradition: his followers cut off their pigtails and allowed their hair to grow as in the past. Hong's followers pressed on from Nanking, and in 1853-1855 they advanced nearly to Tianjin (Tientsin), just outside Beijing, ; but they failed to capture Beijing itself.[Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

"The new Taiping state faced the Europeans with big problems. Should they work with it or against it? The Taiping always insisted that they were Christians; the missionaries hoped now to have the opportunity of converting all China to Christianity. The Taiping treated the missionaries well but did not let them operate. After long hesitation and much vacillation, however, the Europeans placed themselves on the side of the Manchus. Not out of any belief that the Taiping movement was without justification, but because they had concluded treaties with the Manchu government and given loans to it, of which nothing would have remained if the Manchus had fallen; because they preferred the weak Manchu government to a strong Taiping government; and because they disliked the socialistic element in many of the measured adopted by the Taiping.

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: Hong Xiuquan’s followers “swept out of the south of China up to the Yangtze, and established their heavenly kingdom there in Nanjing, with Hong as the Heavenly King and the other commanders as the King of the West, the King of the East, and so on. Their advance against one of the greatest empires in history was surprisingly easy, says Fenby. The Qing dynasty's famous troops, the Banner troops, which had conquered China in the mid 17th Century had gone downhill. "By the mid-19th Century these Banner troops have become dissolute, opium-smoking, corrupt, very inefficient for the most part. And the Chinese mercenaries who fought for the Qing were even worse. So I won't say the Taiping had it easy but their opponents were in a pretty terrible state." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, September 17, 2012 /]

Hong showed peasant rebellion could work in the modern age. This was one of the lessons the Communists took from the Taipings. The two rebellions in fact had much in common, but - one key difference - while Hong started lucky and got unlucky, Mao had it the other way round. By 1860, Hong's heavenly kingdom extended across huge swathes of China and his troops were preparing to march on Shanghai. But his luck was about to run out. The Europeans had decided he was a threat to business. So they joined forces with the Qing armies they themselves had just been fighting. In the Heavenly Capital, the Heavenly Kingdom was anything but.

Destroying the bandits lairs in Tianjiazhen

Collapse of the Taiping Rebellion Movement

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “At first it seemed as if the Manchus would be able to cope unaided with the Taiping, but the same thing happened as at the end of the Mongol rule: the imperial armies, consisting of the "banners" of the Manchus, the Mongols, and some Chinese, had lost their military skill in the long years of peace; they had lost their old fighting spirit and were glad to be able to live in peace on their state pensions. Now three men came to the fore—a Mongol named Sengge Rinchen (Seng-ko-lin-ch'in), a man of great personal bravery, who defended the interests of the Manchu rulers; and two Chinese, Zeng Guofan (Tsêng Kuo-fan 1811-1892) and Li Hongzhang (Li Hong-chang (1823-1901), who were in the service of the Manchus but used their position simply to further the interests of the gentry.

The Mongol saved Beijing from capture by the Taiping. The two Chinese were living in central China, and there they recruited, Li at his own expense and Zeng out of the resources at his disposal as a provincial governor, a sort of militia, consisting of peasants out to protect their homes from destruction by the peasants of the Taiping. Thus the peasants of central China, all suffering from impoverishment, were divided into two groups, one following the Taiping, the other following Zeng Guofan. Zeng’s army, too, might be described as a "national" army, because Tsêng was not fighting for the interests of the Manchus. Thus the peasants, all anti-Manchu, could choose between two sides, between the Taiping and Zeng Guofan. Although Zeng represented the gentry and was thus against the simple common people, peasants fought in masses on his side, for he paid better, and especially more regularly. Tsêng, being a good strategist, won successes and gained adherents. Thus by 1856 the Taiping were pressed back on Nanking and some of the towns round it; in 1864 Nanking was captured.

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: As military victory turned into defeat, Hong became increasingly paranoid, his followers starved and his court spiralled into intrigue and violence. "Hong himself retreated to his palace with his 60 or so concubines listening to music played on an organ taken from the local Christian church and the generals all fought among one another. By the end of the Taiping era at least 10 million had died, some say 20 million. Eyewitnesses described the Yangtze valley as littered with rotting corpses. No-one knows exactly how Hong Xiuquan himself died. His decomposed body was discovered in his palace by a Qing general - an ignominious end for a challenger to empire and the opening of a terrible chapter in China's cycle of fragmentation. [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, September 17, 2012]

End of the Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion finally was put down by Qing armies assisted by British army regulars and American mercenaries who were called into action when the Taiping forces neared Shanghai. The Qing, American and British forces surrounded the Taiping leaders in their capital of Nanjing and shelled the city for seven months until Hong committed suicide from drinking poison and the rebellion ended. The rebellion probably would have succeeded if the Western powers had allied themselves with rebels instead of the Emperor but the Westerners preferred dealing the weak Qing dynasty, which they could easily control.

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “ In the case of the T'ai-p'ing rebellion selfishness and suspicion ultimately caused the ruin of that formidable movement which seemed for more than a decade to threaten the very existence of the Empire.” After their failure to take Shanghai in 1861, the Taiping movement went into decline. At that time, the Qing government was experiencing both internal and external pressures from the Taiping Army and the English and French troops from the Second Opium War. The burning of Summer Palace took place. Emperor Xianfeng made an escape to the Rehe Mountain Resort, where he eventually died. The Qing government finally crushed the rebellion with the help of British and French forces.

Capture of Taping leader Lin Feng-Xiang

One of the most remarkable mercenaries was Frederick Townsend Ward, an American freebooter who was trained by the "filibuster" army of William Walker in Latin America. Ward led soldiers up walls with ladders in the face of enemy fire and was wounded 15 times before he finally died two months shy of his 31st birthday. The Chinese considered him so lucky and invulnerable they raised a religious shrine in his honor, where Chinese prayed for good luck and strength.

After the last Taiping rebels were crushed in Nanjing, the victorious Qing general wrote: "Not one of the 100,000 rebels in Nanjing surrendered themselves when the city was taken, but in many cases gathered together and burned themselves and passed away without repentance. Such a formidable band of rebels has been rarely known ancient times to the present."

“To defeat the rebellion, the Qing court needed, besides Western help, an army stronger and more popular than the demoralized imperial forces. In 1860, scholar-official Zeng Guofan (1811-72), from Hunan Province, was appointed imperial commissioner and governor-general of the Taiping-controlled territories and placed in command of the war against the rebels. Zeng's Hunan army, created and paid for by local taxes, became a powerful new fighting force under the command of eminent scholar-generals. Zeng's success gave new power to an emerging Han Chinese elite and eroded Qing authority. Simultaneous uprisings in north China (the Nian Rebellion) and southwest China (the Muslim Rebellion) further demonstrated Qing weakness.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Acting on orders from the Qing court, Zeng Guofan gathered a special militia in Hunan that came to be known as the Xiang army. The ensuing war between the Xiang and Taiping armies lasted many years before finally ending in 1864 with the capture of the Taiping capital of Tianjin by Zeng Guoquan (Zeng Guofan's younger brother). This defeat brought the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace to its end. Zeng Guoquan first laid siege to Tianjin in 1862. In July of 1864, he captured the city by directing his army to dig tunnels under the city's fortifications, fill them with gunpowder, and blow up the city walls. At the height of the campaign against the Taiping rebels in 1863, a detachment of the Anhui militia under the command of Miao P'ei-lin rebelled and laid siege to the city of Meng-ch'eng. The Qing army quickly mobilized to relieve the siege and launched a merciless assault against the rebels. After Miao P'ei-lin was killed by his subordinates, the surviving rebels fell swiftly. “In 1863, several detachments of the Qing army under the command of Governor-general Ch'en Kuo-jui moved to lift the siege of Meng-ch'eng.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Legacy and Lessons of the Taiping Rebellion

A plaque at the Taiping Rebellion Museum in Nanjing reads: “The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom stood against corruption of the Qing Dynasty, but collapsed under its own corruption. We can learn from this history.” Stephen R. Platt wrote in the New York Times, “ Schoolchildren in China in the 1950s and “60s were taught that the Taiping were the precursors of the Communist Party, with Hong as Mao’s spiritual ancestor. That analogy has now fallen by the wayside, for China’s government is no longer in any sense revolutionary. So it makes sense that in recent years, the Taiping have often been depicted negatively, as perpetrators of superstition and sectarian violence and a threat to social order. The Chinese general who suppressed them, Zeng Guofan, was for generations reviled as a traitor to his race for supporting the Manchus but has now been redeemed. Today he is one of China’s most popular historical figures, a model of steadfast Confucian loyalty and self-discipline. Conveniently for the state, his primary contribution to China’s history was the merciless crushing of violent dissent. [Source: Stephen R. Platt, New York Times, February 9, 2012. Platt is an associate professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the author of “Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War” ***]

Suppression of the Taiping Rebellion

"Beijing has learned its lessons from the past. We see this in the swift and ruthless suppression of Falun Gong and other religious sects that resemble the Taiping before they became militarized. We can see it in the numbers of today’s “mass incidents.” One estimate, 180,000 in 2010, sounds ominous indeed, but in fact the sheer number shows that the dissent is not organized and has not (yet) coalesced into something that can threaten the state. The Chinese Communist Party would far rather be faced with tens or even hundreds of thousands of separate small-scale incidents than one unified and momentum-gathering insurgency. The greatest fear of the government is not that violent dissent should exist; the fear is that it should coalesce .***

"The rebellion holds lessons for the West, too. China’s rulers in the 19th century were, as they are today, generally loathed abroad. The Manchus were seen as arrogant and venal despots who obstructed trade and hated foreigners.... Given the precarious state of our economy today, and America’s nearly existential reliance on our trade with China in particular, one wonders: for all of our principled condemnation of China’s government on political and human rights grounds, if it were actually faced with a revolution from within “ even one led by a coalition calling for greater democracy “ how likely is it that we, too, wouldn’t, in the end, find ourselves hoping for that revolution to fail? The Taiping Rebellion bears the strongest warnings for the current government. The revolt suggests caution for those who hope for a popular uprising “ a Chinese Spring “ today." ***

After the Taiping Rebellion

Gordon G. Chang wrote in the New York Times: After destroying its enemy, the tottering Qing dynasty lasted for almost five decades, until another uprising, again led by Chinese nationalists, would bring an end to two millenniums of imperial rule. In one sense, the earlier challenge to the Manchus never ended. The leader of the 1911 revolution was Sun Yat-sen, a Christian doctor inspired by tales of the Taiping and known to his friends as “Hong Xiuquan.” [Source: Gordon G. Chang, New York Times, March 30, 2012]

We will never know whether Hong Rengan and his cousin would have ruled better than the debauched Qing, but China today is, as in the pre-Taiping era, volatile, plagued by widespread protests, strikes and insurrections (and, as then, the instability follows a period of intense globalization). Unfortunately, the country has not yet broken what one Western commentator in the mid-1850s called “a natural cycle” of rebellion.

Perhaps instability is ingrained in China’s political culture, but a century and a half ago there seemed to be a moment when the Chinese might have changed that pattern. As Platt notes, the Taiping movement came close to overwhelming traditional ways and bringing China into the modern world.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Ohio State University, Columbia University, Taipinng map, St Martins edu.

.

Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated: August 2021