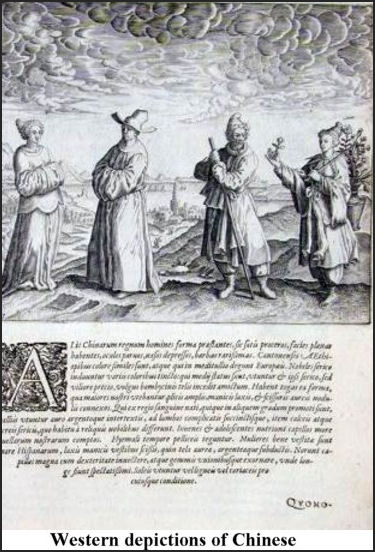

CHINA IN THE 19TH CENTURY

Describing Shanghai in 1862, two decades after the first Opium War, Takasugi Shinsaku, a young Japanese man, wrote in his diary: "There are merchant ships and thousands of battleships from Europe anchored here. The boat slips are filled with masts." The Western-style architecture on the Bund was "beyond description." A fortress about five kilometers was situated on the Huangpu River. Behind the fortress walls was the old city of Shanghai and the British and French settlements lay outside this. The fortress was demolished at the beginning of the 20th century, and today a beltway runs on its former grounds. [Source: Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 9, 2014]

At that time the contrast between the inside and the outside of the castle walls was dramatic. "The inside was less advanced, dark and poor, whereas the Shanghai settlement was modern, developed and prosperous," said Prof. Chen Zuen, who teaches the modern history of Shanghai at National Donghua University. "There was a great contrast in living conditions inside and outside the walls.” Takasugi wrote: “When the British or French walk down the street, the Qing people all avoid them and get out of the way. Shanghai has become like a British or French territory. Japan must keep its guard up." Takasugi was impressed by his visit to the Wen Miao (Confucian temple), located centrally within the castle walls. The land had been conceded to the British Army back then in order to protect Shanghai from rebels. Seeing that the British Army acted as if they owned the place, Takasugi jotted down in his diary, "Deplorable, indeed."

Wei Yuan in the early 19th century was the first major intellectual to insist that the mighty Chinese Empire had fundamental flaws.

Good Sources on 19th and 20th Century Shanghai and Expatriate History For information on Shanghai and China in the 19th century try the single letters column with letters about China in the British national newspapers like The Times at that time. Try the writings of people like Samuel Pollard, Grist, Samuel Clarke’s "Among the Tribes in South-West China" and so on, Edwin Dingle’s “ Across China on Foot “ online, masses of writings by traders and their families, visitors, diplomats, soldiers, journalists, missionaries, writers, artists. For some American attitudes of the time, no different from most of those of the British, take Justus Doolittte’s “ The Social Life of the Chinese “ , or Arthur Henderson Smith’s “ The Chinese Character “ which you can find online. There are lots of patronizing and condescending remarks about Chinese and their deviousness and corruption and concern for face and so on. [Source: Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

Also worth a look is Jane Hunter's seminal work, “ The Gospel of Gentility:American Women Missionaries in Turn-of-the-Century China “ (Yale University Press, 1984); “ Prostitution and Sexuality in Shanghai: A Social History, 1849-1949 “ by Christian Henriot (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); “ Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution and Modernity in Twentieth-Century Shanghai “ by Gail Hershatter (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); “ Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals, and Entertainment Culture, 1850-1910 “ by Catherine Vance Yeh, (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006); The Sing Song Girls of Shanghai by Han Bing; Eileen Chang books (See Literature)

Foreigners in China: 19th Century Tea Trade in China Harvard Business School ; Early Chinese Emmigrants to America: Central Pacific Railroad Museum cprr.org/Museum ; Chinese Americans Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Taiping Rebellion: Taiping Rebellion.com taipingrebellion.com ; Wikipedia Taiping Rebellion article Wikipedia ; Boxer Rebellion National Archives archives.gov/publications ; Modern History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall ; San Francisco 1900 newspaper article Library of Congress ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Cox Rebellion PhotosCaldwell Kvaran ; Eyewitness Account fordham.edu/halsall ; Sino-Japanese War.com sinojapanesewar.com ; Wikipedia article on the Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ;

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu ; Opium Wars : Emperor of China’s War on Drugs Opioids.com Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com : HISTORY OF SHANGHAI: FOREIGNERS, CONCESSIONS AND DECADENCE Article factsanddetails.com ; OPIUM WARS PERIOD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF CHINESE AMERICANS AND IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com ; TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com; BOXER REBELLION factsanddetails.com; EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com; PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China" by Julia Lovell (Picador, 2011) Amazon.com; “Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age”by Stephen R. Platt, Mark Deakins, et al. Amazon.com; "Opium Regimes, China, Britain and Japan, 1839-1952" edited by Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi Amazon.com; "Sea of Poppies" by Amitva Ghosh (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008) a novel set during the Opium Wars mostly in India but also in China Amazon.com; “The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty” by Haijian Mao, Joseph Lawson Amazon.com; “The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700–1845" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 11: Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911, Part 2" by John K. Fairbank and Kwang-Ching Liu Amazon.com; Amazon.com;

Europeans Increase Their Presence in China

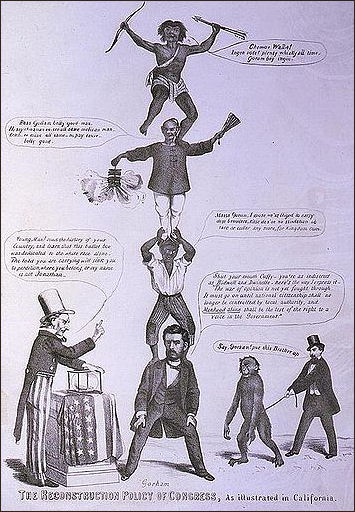

George Congdon Gorham cartoon

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Following the 1742 degree of Benedict XIV the Qing government regarded Catholics, with the possible exception of some Jesuits who were already favored by the imperial court, with suspicion and strictly contained their activities. Meanwhile the Qing’s economic relationship with Europe did not abate, though here also the Qing made every effort to contain their encroachment. When opium entered the picture in the early 1800s, however, the situation deteriorated significantly for the Qing. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos ]

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Great Britain had made several attempts to improve her trade relations with China, but the mission of 1793 had no success, and that of 1816 also failed. English merchants, like all foreign merchants, were only permitted to settle in a small area adjoining Canton and at Macao, and were only permitted to trade with a particular group of monopolists, known as the "Hong". The Hong had to pay taxes to the state, but they had a wonderful opportunity of enriching themselves. The Europeans were entirely at their mercy, for they were not allowed to travel inland, and they were not allowed to try to negotiate with other merchants, to secure lower prices by competition. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The Europeans concentrated especially on the purchase of silk and tea; but what could they import into China? The higher the price of the goods and the smaller the cargo space involved, the better were the chances of profit for the merchants. It proved, however, that European woollens or luxury goods could not be sold; the Chinese would probably have been glad to buy food, but transport was too expensive to permit profitable business. Thus a new article was soon discovered—opium, carried from India to China: the price was high and the cargo space involved was very small. The Chinese were familiar with opium, and bought it readily. Accordingly, from 1800 onwards opium became more and more the chief article of trade, especially for the English, who were able to bring it conveniently from India. Opium is harmful to the people; the opium trade resulted in certain groups of merchants being inordinately enriched; a great deal of Chinese money went abroad. The government became apprehensive and sent Lin Tsê-hsu as its commissioner to Canton. In 1839 he prohibited the opium trade and burned the chests of opium found in British possession. The British view was that to tolerate the Chinese action might mean the destruction of British trade in the Far East and that, on the other hand, it might be possible by active intervention to compel the Chinese to open other ports to European trade and to shake off the monopoly of the Canton merchants.

British Become Involved in China

British penetration into China was different than it was into India and other places. Britain never controlled large amounts of territory. Its control was centered more on directly controlling trade under a very weak national government and relying less on trying to control local leaders as was done in India.Intervention by the British in China was spearheaded not so much by the British government as it was by companies like Jardine and Matheson (See Below). Taipans, the heads of the big Western companies, dealt with their Chinese workers with Chinese go-betweens known as compradores.

Nicholas Tapp of Australian National University wrote: “The British Government was really only incidentally concerned in the British Empire. Most of the Empire was “won” by traders like Jardine and Matheson in Hong Kong (See Below) who then ‘strong-armed’ the UK Government, often against considerable opposition (this is where the letters to The Times are interesting, as also are Parliamentary Questions of the time, in showing you how the majority of right-minded thinking British middle-classes “ particularly vicars but not confined to them - were shocked by opium and were not that into taking on more foreign territories to administer at all), into taking over some realm they had seized de facto control of." [Source:Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

"The British decided not to directly colonize China and used trade instead," Tapp wrote. "Colonization mostly followed trade. Look at the history of Hong Kong for what MIGHT have happened in China if all China had been in the same situation as Shanghai with its international concessions. But of course, it wasn’t." [Source: Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

Opium Wars

Foreign traders came to China by sea, bringing opium with them. The Qing banned opium in 1800, but the foreigners did not heed that decree. In 1839, the Chinese confiscated twenty thousand chests of the drug from the British. In 1840 the British retaliated,. British ships-of-war appeared off the south-eastern coast of China and bombarded it — and the four Opium Wars began. In 1841 the Chinese opened negotiations. As the Chinese concessions were regarded as inadequate, hostilities continued; the British entered the Yangtze estuary and threatened the old capital of Nanking. In this first armed conflict with the West, China found herself defenseless owing to her lack of a navy, and it was also found that the European weapons were far superior to those of the Chinese. The result was a defeat for China and the establishment of Western settlements at numerous seaports. Eleanor Stanford, "Countries and Their Cultures", Gale Group Inc., 2001; [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ “Western military weapons, including percussion lock muskets, heavy artillery, and paddlewheel gunboats, were far superior to China's. Britain's troops had recently been toughened in the Napoleonic wars, and Britain could muster garrisons, warships, and provisions from its nearby colonies in Southeast Asia and India.

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “The first shots were fired when the Chinese objected to the British attacking one of their own merchant ships. The Royal Navy established a blockade around Pearl Bay to protest the restriction of free trade … in drugs. Two British ships carrying cotton sought to run the blockade in November 1839. When the Royal Navy fired a warning shot at the second, The Royal Saxon, the Chinese sent a squadron of war junks and fire-rafts to escort the merchant. HMS Volage's Captain, unwilling to tolerate the Chinese "intimidation," fired a broadside at the Chinese ships. HMS Hyacinth joined in. One of the Chinese ships exploded and three more were sunk. Their return fire wounded one British sailor. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016 ]

“Seven months later, a full-scale expeditionary force of 44 British ships launched an invasion of Canton. The British had steam ships, heavy cannon, Congreve rockets and infantry equipped with rifles capable of accurate long range fire. Chinese state troops — "bannermen" — were still equipped with matchlocks accurate only up to 50 yards and a rate of fire of one round per minute. Antiquated Chinese warships were swiftly destroyed by the Royal Navy. British ships sailed up the Zhujiang and Yangtze rivers, occupying Shanghai along the way and seizing tax-collection barges, strangling the Qing government's finances. Chinese armies suffered defeat after defeat.”

See Separate Article OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com

"Unequal Treaties" After the Opium War

18th century Chinese image

of an English sailor

The result of the First Opium War was a disaster for the Chinese. By the summer of 1842 British ships were victorious and were even preparing to shell the old capital, Nanking (Nanjing), in central China. The emperor therefore had no choice but to accept the British demands and sign a peace agreement. This agreement, the first of the "unequal treaties," opened China to the West and marked the beginning of Western exploitation of the nation. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: “The result was a defeat for China and the establishment of Western settlements at numerous seaports. The foreigners took advantage of the Qing's weakened hold on power and divided the nation into "spheres of influence." Another result of the Opium Wars was the loss of Hong Kong to the British in 1842. The 1840 Treaty of Nanjing gave the British rights to that city "in perpetuity." An 1898 agreement also "leased" Kowloon and the nearby New Territories to the British for 99 years, significantly expanding the size of the Hong Kong colony. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

One unequal treaty, which forced China to involuntarily open new "treaty ports" and pay further indemnities to European powers, was drawn up after China refused to apologize for a torn British flag. In the Convention of Peking in 1860 China opened up more ports to foreigners and paid more reparations and allowed British ships to carry indentured Chinese laborers (“coolies”) to the United States and legalized the opium trade.Neither the Chinese emperor or Queen Victoria were happy about the outcome of the Opium War and the treaties. Elliot became the chargé d'affaires in the Republic of Texas and the Chinese official who negotiated the treaty was sent to Tibet.

Treaty of Nanking and Its Aftermath

After the Chinese surrendered,the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) was signed on board a British warship by two Manchu imperial commissioners and the British plenipotentiary in August 1842. The first of several "unequal treaties," it that gave up the island Hong Kong to the British "in perpetuity," opened five ports to European trade, forced China to pay an indemnity of $21 million (around $500 million in today’s money and large sum for a largely impoverished country and bankrupt dynasty) and minimal tariffs on imported goods. It also forced China to continue accepting East India Company opium. The Qing Emperor at first refused to accept the Nanjing Treaty, but another British attack changed his mind. Further concessions were made after the second Opium War in 1860.

The Treaty of Nanjing also limited the tariff on trade to 5 percent ad valorem; granted British nationals extraterritoriality (exemption from Chinese laws). In addition, Britain was to have most-favored-nation treatment, that is, it would receive whatever trading concessions the Chinese granted other powers then or later. The Treaty of Nanjing set the scope and character of an unequal relationship for the ensuing century of what the Chinese would call "national humiliations." The treaty was followed by other incursions, wars, and treaties that granted new concessions and added new privileges for the foreigners.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: In 1842 China was compelled to capitulate: under the Treaty of Nanking Hong Kong was ceded to Great Britain, a war indemnity was paid, certain ports were thrown open to European trade, and the monopoly was brought to an end. A great deal of opium came, however, into China through smuggling—regrettably, for the state lost the customs revenue![Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“This treaty introduced the period of the Capitulations. It contained the dangerous clause which added most to China's misfortunes—the Most Favoured Nation clause, providing that if China granted any privilege to any other state, that privilege should also automatically be granted to Great Britain. In connection with this treaty it was agreed that the Chinese customs should be supervised by European consuls; and a trade treaty was granted. Similar treaties followed in 1844 with France and the United States. The missionaries returned; until 1860, however, they were only permitted to work in the treaty ports. Shanghai was thrown open in 1843, and developed with extraordinary rapidity from a town to a city of a million and a centre of world-wide importance.

“The terms of the Nanking Treaty were not observed by either side; both evaded them. In order to facilitate the smuggling, the British had permitted certain Chinese junks to fly the British flag. This also enabled these vessels to be protected by British ships-of-war from pirates, which at that time were very numerous off the southern coast owing to the economic depression. The Chinese, for their part, placed every possible obstacle in the way of the British. In 1856 the Chinese held up a ship sailing under the British flag, pulled down its flag, and arrested the crew on suspicion of smuggling. In connection with this and other events, Britain decided to go to war. Thus began the "Lorcha War" of 1857, in which France joined for the sake of the booty to be expected. Britain had just ended the Crimean War, and was engaged in heavy fighting against the Moguls in India. Consequently only a small force of a few thousand men could be landed in China; Canton, however, was bombarded, and also the forts of Tientsin. There still seemed no prospect of gaining the desired objectives by negotiation, and in 1860 a new expedition was fitted out, this time some 20,000 strong. The troops landed at Tientsin and marched on Beijing; the emperor fled to Jehol and did not return; he died in 1861. The new Treaty of Tientsin (1860) provided for (a) the opening of further ports to European traders; (b) the session of Kowloon, the strip of land lying opposite Hong Kong; (c) the establishment of a British legation in Beijing; (d) freedom of navigation along the Yangtze; (e) permission for British subjects to purchase land in China; (f) the British to be subject to their own consular courts and not to the Chinese courts; (g) missionary activity to be permitted throughout the country. In addition to this, the commercial treaty was revised, the opium trade was permitted once more, and a war indemnity was to be paid by China. In the eyes of Europe, Britain had now succeeded in turning China not actually into a colony, but at all events into a semi-colony; China must be expected soon to share the fate of India. China, however, with her very different conceptions of intercourse between states, did not realize the full import of these terms; some of them were regarded as concessions on unimportant points, which there was no harm in granting to the trading "barbarians", as had been done in the past; some were regarded as simple injustices, which at a given moment could be swept away by administrative action.

See Separate Article OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com

Jardine and Matheson

The most aggressive Hong Kong opium merchants were William Jardine and James Matheson, a pair of Scotsmen who founded Jardine and Matheson, the famous Hong Kong trading company that was that was subject of the James Clavell novels “Taipan” and “Noble House”. Known as the "iron-headed rat," Jardine was a former doctor who had only one chair in his office — his own. Visitors to his office were forced to stand. Matheson was a nobleman with a more courteous demeanor. He owned the only piano in Canton and paid for English lessons for Chinese.

Jardine-Matheson & Company got its start in the opium trade in 1832, two years after the British government closed down the East India Company monopoly. The initially-London-based company inherited India and its opium from the British East India Company after its mandate to rule and dictate the trade policies of British India is ended.

The two Scotsmen avoided uncertainties in Canton by skipping the Chinese port altogether and establishing relationships with Chinese merchants in other Chinese coastal locations with the help a of Prussian missionary who spoke several Chinese dialects and arranged for missionary ships, carrying Bibles and evangelical literature, to also drop off chests of opium. The missionary who collaborated on the scheme later wrote that opium smuggling "may tend ultimately to the introduction of the gospel."

In 1848, Jardine and Matheson set up an opium and tea trading post in Shanghai, and has been expanding ever since. James Matheson, the nephew of one of the company's founder, ran the company from 1837 to 1849, but eventually left in disgust and returned to England where he became chairman of the Executive Committee for the Suppression of the Opium Trade. By the 1980s, it was estimated that Jardine and Matheson owned about half of Hong Kong. Before the handover of Hong Kong in 1997, the company incorporated in Bermuda rather than Hong Kong but still has offices in Hong Kong and Shanghai.

After the Opium Wars

After the Opium Wars, Britain and other Western powers, including the United States, forcibly occupied “concessions” and gained special commercial privileges. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““By the mid-1800sEuropean soldiers, merchants, and missionaries (both Catholic and Protestant) were establishing a presence in China and moving into cities all along China’s coastline and into interior regions of the country. This influx of Europeans represented an absolute and dramatic threat to China in many ways. The Westerners’ beliefs and customs were vastly different from that of the Chinese, and their ongoing presence represented not only a military disaster but a cultural disaster as well, for it undermined the centrality of the Chinese emperor, as well as the centrality of the Chinese civilization itself. “

After a while the West’s interest in China turned from trade to territory. The second war with Britain (1856–60) was joined by France, resulted in British and French forces capturing Canton in December 1857 and the opening of Tianjin (Tientsin) to foreign trade. Russia acquired its Far Eastern territories from China in 1860. China's defeat in the Sino-French War (1884–85), in which it came to the defense of its tributary, Vietnam, resulted in the establishment of French Indo-China.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “But the result of this European penetration was that China's balance of trade was adverse, and became more and more so, as under the commercial treaties she could neither stop the importation of European goods nor set a duty on them; and on the other hand she could not compel foreigners to buy Chinese goods. The efflux of silver brought general impoverishment to China, widespread financial stringency to the state, and continuous financial crises and inflation. China had never had much liquid capital, and she was soon compelled to take up foreign loans in order to pay her debts. At that time internal loans were out of the question (the first internal loan was floated in 1894): the population did not even know what a state loan meant; consequently the loans had to be issued abroad. This, however, entailed the giving of securities, generally in the form of economic privileges. Under the Most Favoured Nation clause, however, these privileges had then to be granted to other states which had made no loans to China. Clearly a vicious spiral, which in the end could only bring disaster. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The only exception to the general impoverishment, in which not only the peasants but the old upper classes were involved, was a certain section of the trading community and the middle class, which had grown rich through its dealings with the Europeans. These people now accumulated capital, became Europeanized with their staffs, acquired land from the impoverished gentry, and sent their sons abroad to foreign universities. They founded the first industrial undertakings, and learned European capitalist methods. This class was, of course, to be found mainly in the treaty ports in the south and in their environs. The south, as far north as Shanghai, became more modern and more advanced; the north made no advance. In the south, European ways of thought were learnt, and Chinese and European theories were compared. Criticism began. The first revolutionary societies were formed in this atmosphere in the south.

Colonialism, Concessions and Shanghai

The focal point of European intervention into China was Shanghai, a strategically located former weaving and fishing town that was carved up into separate and autonomous European districts known as concessions. Beyond the reach of Chinese laws and taxes, the concessions were self contained worlds with their prisons, police, courts, schools, barracks and hospitals. In addition to this, Shanghai had exclusive parks and gentlemen's clubs that Chinese were not allowed in. Many business were started by former opium traders. Some American enterprises claimed they sold everything.

The British set up their concession in Shanghai in 1842. The same year an American neighborhood called the International Settlement was opened. The French concession was opened in 1847 and around it grew Shanghai's red light district. Russians and Germans arrived later and a Japanese enclave was established in 1895.

In the mid 1850s Shanghai had a population of 50,000. By 1900 it had a million people. By the 1930s, it was the largest trading center in Asia; arguably the most decadent place on the planet; and a city so westernized, it had its own Chinatown.

The British and French also occupied concessions in Tianjin, a port not far from Beijing through which many goods from northern China were transported. The excuse for the occupation of Tianjin was the Arrow incident (See Opium Wars). Between 1895 and 1900 the French were joined there by the Japanese, Germans, Austro-Hungarians, Italians and Belgians

Dalian was developed first by the Russians and later by the Japanese. A fishing town until the late 1800s, it began its transformation into a major deep-water port under the Russians who coveted it because, unlike Vladivostock to the north, its waters didn't freeze over in the winter. The Japanese took over Dalian after the end of the Russo-Japanese War and for the most part completed the Russian plan for the city.

Perceptions at Home of Foreign Involvement in “Decadent” China

There was a lot of anger in Britain over what was happening in China. On the opium wars, there are a number of angry letters in the letter columns of The Times from missionaries and well-meaning Whigs inveighing against the opium trade and all its ills. There were heated debates in Parliament about the merits and ills of supporting or being involved in the trade in any way.

Read any of the very readable life-story books written by the missionaries in Shanghai or West China at the time and see how much they campaigned against the opium trade and its horrible effects. Look at the Permanent Committee for the Promotion of Anti-Opium Societies, set up in Shanghai by the Englishman Arthur Moule in 1890, of which GW Clarke was a member. Look at the Executive Committee for the Suppression of the Opium Trade and think about what that must have meant for what was going on here at that time. [Source: Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

Remember this was a time when old ladies in US and UK and Europe and everywhere regularly took laudanum (opium derivative) for their coughs and nerves” The drug was not illegal anywhere. It was in the 1910s that some organized international movement against this (impelled mainly by British campaigners) took momentum and resulted in banning it in the era;y 19th century. Look at Alfred McCoy’s wonderful book on The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia, great chapter on history of opium for a start (“Opium for the natives”).

See Separate HISTORY OF SHANGHAI: FOREIGNERS, CONCESSIONS AND DECADENCE Article factsanddetails.com

Strange Views of Foreigners by 19th Century Chinese

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “When the British troops occupied North-China, the Chinese soldiers for the first time saw foreign ladies mounted on the backs of ponies. The singular appearance, gave rise to the tale — doubtless implicitly believed to this day — that there is a variety of Occidental women, with but one leg! [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

“A country woman expressed the opinion that the remarkable whiteness of foreign children is due to the practice of their mothers of licking them every day, as cats do their kittens! Foreign newspapers, containing cartoons intended to be humorous, are very ill-adapted to circulation in China. An intelligent Muslim inquired of a foreign physician in China, as to the habitat of the people with wings, who live in trees. On investigation; it turned out that his ideas were based upon pictures which he had seen on a match-box!

“The Chinese have an abiding faith in the existence of regions unvisited by man, a faith analogous to that of children with regard to “fairy land." Foreigners are often asked whether there are not countries in which there are only, women, others in which the heads of the inhabitants are like those of dogs. In one instance, this belief was confirmed in a Chinese woman, who happened to see a foreign illustrated paper, containing political cartoons representing, certain individuals as dogs. “Oh, to be sure," she remarked, "they live in the dog-head kingdom." A servant who opened a kit of split mackerel was surprised to find that they had but one eye, etc. An older servant assured him that this was an "old time custom" of some foreign fish! Another singular notion of the Chinese, based upon a much quoted book, is a belief that there is a land in which the inhabitants have holes entirely through their stomachs. We have heard of a most unsympathetic foreigner, who being appealed to on this point, by a Chinese, immediately decided that there certainly is such a kingdom. "And where is it?" he was asked. "In China," was the answer. The Chinese who had proposed the question insisted that, this could not be, as he had. never heard pf such a thing. "Take off your coat," was the reply, and "I will show you." The man did as requested, whereupon the foreigner fixed his eyes attentively upon the centre of the man's abdominal region, seemed much disappointed, observed sadly, Ah I see you have sewed it up

Living in Yantai — a Chinese Treaty Port — in the 1870s and 80s

Ian Gill wrote in the South China Morning Post: “My wife and I travelled to Yantai, formerly known as Chefoo A few months earlier, I must confess, I had not heard of Chefoo. Then I made the astonishing discovery that my English great-grandparents — Edward and Mary Ann Newman — had moved from Hong Kong to northern China in 1873, during a period when many Chinese were flocking south to the fledgling British colony. Following the Treaty of Tientsin (1858), Chefoo had opened as a treaty port in 1861, presenting opportunities for the intrepid. But my forebears were neither colonial administrators, nor merchants, nor missionaries. They had no organisation to bail them out if things went wrong.[Source: Ian Gill, South China Morning Post, April 7, 2017]

In 1873, Yantai was walled town of 10,000, with a few dozen foreign residents. The Newmans had arrived there on a three-day journey by steamer from Hong Kong. Why did the Newmans move to Yantai. “Mary Ann may also have worried about Hong Kong’s unhealthy climate and high crime rate. On Old Bailey Street, the Newmans lived directly opposite Victoria Prison and they had only to walk outside to see Sikh policemen parading Chinese offenders in wooden stocks along Hollywood Road. By contrast, the Newmans would have heard of Chefoo’s reputation as having the healthiest climate among the treaty ports, neither too hot in summer nor too cold in winter and free of tropical vapours.

In 1874, according to a Chefoo directory, Edward and Mary Ann became proprietors of the Family Hotel, taking over from Mr Bielfield, a German. So that was their siren call – the chance to be free from wage slavery and become masters of their destiny. The Newmans found a small international community that included consular officials, missionaries and agents representing dozens of mercantile, shipping, insurance and banking enterprises. Some obligatory features of a treaty port were already in place: an Imperial Maritime Customs office, the Chefoo Club and the Chefoo Race Club, which held horse races every May on the beach.

“But Chefoo’s anticipated commercial boom did not arrive and the Newmans must have wondered if they had made a disastrous mistake. For many years, Chefoo was isolated from its hinterland by dirt tracks that could accommodate only mules, horses and donkeys, not even carts. Thus, the port remained more of a landing stage than a trading centre. There were other issues. The Chinese didn’t take to imports such as British cotton goods, prefer―ring their own. Also, inadequate steamer services prevented foreigners from exporting as much beancake as they would have liked. The British recognised the restrictions of Chefoo’s potential and never established a formal foreign settlement, with defined boundaries and a proper municipal council.

“Meanwhile, the Newmans settled down to their new life. Unusually for Victorian wives, Mary Ann used her previous hotel experience as Edward’s partner in business while continuing to increase her family. On March 30, 1874, Edward signed the book at the British consulate to register their second daughter, Ellen, born the previous month. Another son, George James Thomas, arrived on October 4, 1875. Two years later, at the age of 42, Mary Ann delivered Amy Dorothy Edith, on August 31, 1877, but the infant died at three months. Between their family, staff and hotel guests, the Newmans led an eventful and largely self-contained life, avoiding the boredom that plagued so much of treaty port life.

“Chefoo, fortunately, prospered through other ways beside trade. Warships of all flags were frequent visitors, keeping watch as China tried to create a modern fleet in the north. Above all, Chefoo’s European climate was a big hit with convalescents and retirees, as well as holidaymakers and officials seeking respite from the heat of Beijing. All this was a boon for the Family Hotel.

“In 1879, the Newmans benefited from a fantastic stroke of luck. James Hudson Taylor, the British founder of the China Inland Mission, had become seriously ill on a voyage back to China and was recuperating in Chefoo. One day, he was walking along East Beach with fellow missionary Charles Judd when a farmer approached them and asked if they wanted to buy his bean field. This encounter led to the development of a large China Inland Mission compound that would include prestigious schools for boys and girls.

“The mission’s first building was a sanatorium on the other side of San Lane from the Family Hotel. Part of the hospital was used as a preparatory school, which opened in 1880 with three of Judd’s sons as its only pupils. In January 1881, they were joined by Frank Newman, eight years old, and his brother George, aged five. Later, the Newmans’ daughters, Annie and Ellen, attended the girls’ school.

“Modelled on the British public school system, Chefoo School would acquire a reputation as the finest school east of Suez. In anticipation of a boom, the Newmans added a second floor to the hotel. Not only was their gamble paying off, but their children were getting a better education than they would have had in Britain. Then, on August 13, 1883, at the height of the summer season, Edward rose to cope with a typical day. But it turned out to be far from business as usual. Sometime that morning, he experienced a sharp pain, collapsed and died. A death notice in the North China Herald, published in Shanghai, read: “At Chefoo Family Hotel, on the morning of the 13th of August, of Apoplexy, Mr. Edward Newman, to the great grief of his widow and family.”

Chinese in Shanghai

Some 200,000 Chinese workers helped turn Shanghai into the largest manufacturing city in Asia. Even in the foreign concessions about 90 percent of the residents were Chinese, the vast majority of them workers. Many of these "workers" were 12- and 13-year-old boys and girls who worked 13 hour days, chained to the machines, in slave-like conditions, unable to leave their heavily guarded factory compounds.

coolies

The Cantonese term for Europeans and Americans is gweilo, which literally translates to "devil man" but is often translated as "foreign devil." [Gweilo doesn’t really mean “foreign devils” at all though it is often translated that way. Gwei certainly can be translated as devil(s), but “lo” is just a rather familiar term for a person. “devil man” would be better. ] At the end of the 19th century the poet Yen-shi wrote:

Last year we called him the Foreign Devil

Now we call him "Mr. Foreigner, Sir!"

We weep over the departed but smile when a new wife

takes her place

Ah, the affairs of the world are like the turning of

a wheel

The Chinese in Shanghai also endured opium addiction, starvation, and exploitation by pimps and gangsters. The term "shanghaied" originated with the practice of kidnaping Chinese peasants and drunken drifters to provide cheap labor in foreign countries or to work on undermanned ships. The Chinese word ‘shanghai’, meaning to ruin someone (origin of the loan into English) has nothing to do with the word for the place Shanghai, both characters are written differently and one is in a different tone as well.

It has often been printed that there was sign in front of Huangpu Park in the British quarter that read "No admittance to Dogs and Chinese." Research has shown that this is a myth. There were rules about dogs and there were rules restricting Chinese servants but they were never placed together on the same sign. Nicholas Tapp of Australian National University, “The “dogs and Chinese placard “is a famous canard and it has been disproved that there was ever such a sign. Richard Hughes, for many years editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, said there were a number of regulations about the parks (including Huangpu) including one that the parks were reserved for Europeans, another that no dogs or bicycles were allowed. These were in Chinese, not English. Lynn Pan (famous author on Shanghai and overseas Chinese who lives here) denied that the sign has ever existed, though she said she had seen in a museum hundreds of propaganda replica signs like this produced by the Party for propaganda purposes in the 1960s. There is a conclusive article in the China Quarterly (142. 1995) which goes into the whole history of how the false juxtaposition was spread. The regulations altered in 1903 and 1928. At one point they said only Chinese who attended as servants were admitted. At another point dogs on leads were admitted. And so on. But the shocking juxtaposition which is so horrific, and in English, and as a publically displayed sign, is just a common misapprehension. There were rules about both of these things, but along with many other rules, and not jammed together in this shocking way.” [Source:Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

Russians in Manchuria

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “After the Crimean War, Russia had turned her attention once more to the East. There had been hostilities with China over eastern Siberia, which were brought to an end in 1858 by the Treaty of Aigun, under which China ceded certain territories in northern Manchuria. This made possible the founding of Vladivostok in 1860. Russia received Sakhalin from Japan in 1875 in exchange for the Kurile Islands. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

She received from China the important Port Arthur as a leased territory, and then tried to secure the whole of South Manchuria. This brought Japan's policy of expansion into conflict with Russia's plans in the Far East. Russia wanted Manchuria in order to be able to pursue a policy in the Pacific; but Japan herself planned to march into Manchuria from Korea, of which she already had possession. This imperialist rivalry made war inevitable:

Russia lost the war; under the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1905 Russia gave Japan the main railway through Manchuria, with adjoining territory. Thus Manchuria became Japan's sphere of influence and was lost to the Manchus without their being consulted in any way. The Japanese penetration of Manchuria then proceeded stage by stage, not without occasional setbacks, until she had occupied the whole of Manchuria from 1932 to 1945. After the end of the second world war, Manchuria was returned to China, with certain reservations in favour of the Soviet Union, which were later revoked.

Aurel Stein and 20th Century Explorers of the Silk Road

Explorer David Neel

Western China was caught up in the Great Game. Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, western China and Afghanistan were more important in the Great Game than other Central Asian states because they formed the buffer zone between the Russian Empire and the British-Indian Empire. See Uzbekistan.

In the 1920s, Sven Hedin's Sino-Swedish excavations in Xinjiang and Manchuria unearthed 10,000 strips with writing, Han documents on silk, wall paintings from Turpan and pottery and bronzes.

The most prominent of the Western explorers of the remote parts of China was Sir Aurel Stein (1863-1943), an explorer, linguist and archaeologist who made four expeditions to Central Asia in the early 20th century. Stein was Jewish and born in Hungary. He pioneered the study of the Silk Road and looted Buddhist art from caves in the western Chinese desert. Accompanied by his dog Dash, he carted away a treasure trove of ancient Buddhist, Chinese, Tibetan and Central Asia art and texts in a number of languages from the ancient city of Dunhuang and gave them to the British Museum.

In the late 1920s, Stein trekked over 18,000-foot Karakoram Pass three times and traced the Silk Road through Chinese Turkestan and followed routes on which Buddhism spread to China from India. Stein discovered the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas near Dunhuang in northwest China and carted away 24 cases of artifacts, including silk painting, embroideries, sculptures and 1,000 early manuscripts written in Tangut, Sanskrit and Turkish, which included the world's oldest book, The Diamond Sutra.

Inspired by his “patron saint” Xuanzang, , the 7th century Chinese Buddhist monk, Stein followed the Silk Road described by Xuanzang in his travels from Chang’an (Xian) to India. During his expeditions Stein documented and photographed the ancient locations he visited and found many Silk Road treasures. Among those he took with him were ancient tablets, relics and frescoes. His most important discovery was 40,000 scrolls including the world’s oldest printed text the Diamond Sutra found at Dunhuang in Gansu, western China.

When news got out about Stein's discoveries it set in motion and age of discovery and looting. During the first quarter of the 20th century, archaeologists from Great Britain, Russia, Germany, Japan and other nations competed for shares of Silk Road treasure. These archaeological exploits even got tangled up in what has been termed the Great Game where Great Britain and Russia competed for political influence in Central Asia and Western China. Christian missionaries also made their way out to Xinjiang. Among the most famous were Francesca French and Mildred Cable who wrote the book “The Gobi Desert”.

Humiliation as a Stimulus to China’s Rise

In a review of “Losing Face, Leaping Forward ‘Wealth and Power,’” by Orville Schell and John Delury. Joseph Kahn wrote in the, New York Times, “The humiliations China has suffered at the hands of foreigners over the past century and a half are the glue that keeps the country together. Even $3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves has not healed the psychological trauma of 1842, the year of China’s defeat at the hands of the British in the first Opium War. After that conflict, China was dismembered, first by the European powers, then, more devastatingly, by Japan. Chinese troops expelled the Japanese, and the country was reunified more than 60 years ago. But it is determined to keep the memory of the abuses it suffered from fading into history. [Source: Joseph Kahn, New York Times, July 18, 2013 ~/~]

“Shame often acts as a depressant. But Schell and Delury argue that for generations of influential Chinese, shame has been a stimulant. In one sense, the evidence is not hard to find. The inaugural exhibition at the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square, splashily reopened in 2011, was called “The Road to Rejuvenation,” which treated the Opium War as the founding event of modern China. And it then told a Disneyesque version of how the Communist Party restored the country’s greatness. At the museum of the Temple of Tranquil Seas in Nanjing, the site of the signing of one of the most unequal of China’s treaties with foreign powers, is inscribed this phrase: “To feel shame is to approach courage.” Humiliation has been a staple of Communist Party propaganda. ~/~

“Schell and Delury acknowledge the cynicism behind the party’s use of shame as a nationalist rallying cry. But their book makes the case that such feelings represent a deep strain in the Chinese psyche, which the country’s current leaders have inherited as part of their cultural DNA. To love China means to share a passionate commitment to overcoming the loss of face suffered in the 19th century, to ensure that the defeats of the past will never be suffered again.” What the book “offers readers is the idea that the most important Chinese intellectuals and political leaders, from the Empress Dowager Cixi to Deng Xiaoping, were united in the national quest to avenge humiliation. They all felt shame, and used it as the path to “wealth and power.” ~/~

“Many of the steps they took were disastrous. Over a century and a half China has stumbled through imperial rule, warlordism, republicanism and Communism. Its leaders have reigned through feudalism, fascism, totalitarianism and capitalism. But for Schell and Delury, none of those conflicting systems or ideologies in the end defined China, or even the leaders who imposed them. Instead, the constant through China’s recent history is the persistent search for something — anything — that would bring restoration. ~/~

Cage with Mrs. Noble

“The reformers of the early 19th century were the first to declare that China was “big and weak,” and though the statement was true, at the time it bordered on heresy. The solution the early reformers proposed was “to self-strengthen,” which would be achieved by adopting selective Western technologies and methods. By the turn of the 20th century, after a series of even more severe setbacks, prescriptions from scholars and advisers grew bolder. Liang Qichao, who founded the Sense of Shame Study Society, felt Chinese culture bred timidity. He wanted to destroy China’s Confucian “core” and rebuild the country from scratch with imported Western ideas. That was the template China’s Nationalist leaders, Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, followed for years as they struggled to figure out which Western political, cultural and economic formulas could reinvigorate their country. ~/~

“Much of Mao’s brutally destructive legacy — the mass killings of class enemies, the famine-inducing Great Leap Forward, the catastrophic Cultural Revolution — should be viewed,” Schell and Delury “suggest, less through the prism of radical Marxism than as an attempt to exorcise Confucian passivity. Mao especially wanted to eliminate the traditional ideal of “harmony” and replace it with a mandate to pursue “permanent revolution,” an inversion of Chinese cultural traditions he believed essential to unleashing the country’s productive forces. Schell and Delury do not say that Mao intended to pave the way for Deng and his acolytes, including Zhu Rongji, whom they present as the most successful implementer of Deng’s ideas. But they do seek to show that Deng’s pursuit of market-oriented reforms might well have met far more resistance if Mao had not bequeathed him a blank slate — that is, a ruling party exhausted by bloody campaigns and a people purged of their ancient notions of order. Deng’s tactics may have been the polar opposite of Mao’s, but their goals, realized partly under Deng and rather spectacularly by his successors, were precisely the same.” ~/~

Book: “Losing Face, Leaping Forward ‘Wealth and Power,’” by Orville Schell and John Delury. 2013]

Image Sources: 1) Western image of Chinese Columbia University; 2) English sailOr, Brooklyn College; 3) Opium smoking, Normal Opium museum.; 4) Victor Sasson, Columbia University; Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021