HISTORY AND NAME OF SHANGHAI

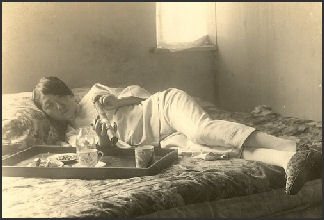

opium smoker

Shanghai is a young city by Chinese standards, One noodle shop owner told the Washington Post, “If you want to see 2,000 years of history, you go to Xian. If you want 500 years of history, go to Beijing. If you want to know what will happen, you go to Shanghai."

Up until 1842 Shanghai was just a small fishing town. After the Opium Wars (1839-42) and the bombardment of the Chinese fort at Huangpu by the British man-of-war Nemesis, the British coerced the Chinese into making Shanghai a "treaty port" with a self-governing British district called a concession. Quick on the heels of the British came sizable populations of Americans, French and Russians. By the 1850s, Shanghai had a community of 60,000 expatriates, most of whom lived in separate concessions which were divided along national lines. In 1863, the British and Americans merged their territory into the International Concession.

The two Chinese characters in the city's name “Shàng” ("above") and “hi” ("sea"), together mean "Upon-the-Sea". The earliest occurrence of this name dates from the 11th century Song Dynasty, at which time there was already a river confluence and a town with this name in the area. An older name for Shanghai is Shēn, from Chunshen Jun, a nobleman and locally revered hero of the third-century B.C. state of Chu. From this, it is also called Shēnchéng ("Shen City"). Sports teams and newspapers in Shanghai often use the character for this name in their names. The city has also been known by the English nicknames "Pearl of the Orient" and "Paris of the East". [Source: Wikipedia]

The population of Shanghai was 24,870,895 in 2020; 23,019,148 in 2010; 16,407,734 in 2000; 13,341,896 in 1990; 11,859,748 in 1982; 10,816,458 in 1964; 6,204,417 in 1954; 4,630,000 in 1947; 3,727,000 in 1936-37. [Source: Wikipedia, China Census]

Book: Shanghai by Harriet Sergeant (John Murray, 1998) is an interesting and readable account of Shanghai's colorful history; Film: Jia Zhangke I Wish I Knew

Shanghai in Imperial Times

Shanghai is not particularly known for its ancient history. But it does have some. Shanghai is officially abbreviated ('Hù) in Chinese, a contraction of (Hù Dú, lit "Harpoon Ditch"), a 4th or 5th century Jin name for the mouth of Suzhou Creek when it was the main conduit into the ocean. This character appears on all motor vehicle license plates issued in the municipality today. Another early name for Shanghai was Huating.. In 751 A.D., during the mid-Tang Dynasty, Huating County was established at modern-day Songjiang, the first county-level administration within modern-day Shanghai. Today, Huating appears as the name of a four-star hotel in the city. [Source: Wikipedia]

During the Song Dynasty (AD 960–1279) Shanghai was upgraded in status from a village to a market town in 1074, and in 1172 a second sea wall was built to stabilize the ocean coastline, supplementing an earlier dyke. From the Yuan Dynasty in 1292 until Shanghai officially became a city in 1927, the area was designated merely as a county seat administered by the Songjiang prefecture. [Source: Wikipedia]

Two important events helped promote Shanghai's development in the Ming Dynasty. A city wall was built for the first time in 1554 to protect the town from raids by Japanese pirates. It measured 10 meters high and 5 kilometers in circumference. During the Wanli reign (1573–1620), Shanghai received an important psychological boost from the erection of a City God Temple in 1602. This honour was usually reserved for places with the status of a city, such as a prefectural capital not normally given to a mere county town, as Shanghai was. It probably reflected the town's economic importance, as opposed to its low political status.

During the Qing Dynasty, Shanghai became one of the most important sea ports in the Yangtze Delta region as a result of two important central government policy changes: First, Emperor Kangxi (1662–1723) in 1684 reversed the previous Ming Dynasty prohibition on ocean going vessels – a ban that had been in force since 1525. Second, in 1732 Emperor Yongzheng moved the customs office for Jiangsu province from the prefectural capital of Songjiang city to Shanghai, and gave Shanghai exclusive control over customs collections for Jiangsu Province's foreign trade. Professor Linda Cooke Johnson has concluded that as a result of these two critical decisions, by 1735 Shanghai had become the major trade port for all of the lower Yangtze River region, despite still being at the lowest administrative level in the political hierarchy.

Arrival of Europeans in Shanghai

Shanghai drew international attention in the early 19th due to its nearness to the mouth of the Yangtze River and European recognition of the economic and trade potential of this location. Shanghai lies on the Huangpu River, about 24 kilometers miles upstream from where the Yangtze, the main transportation route for much of China’s economy for centuries, empties into the East China Sea. During the First Opium War (1839–1842), the British man-of-war Nemesis bombarded the Chinese fort at Huangpu and British forces occupied the city. The war ended with the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, which allowed the British to set up “treaty ports.”

The British coerced the Chinese into making Shanghai a "treaty port" with a self-governing British district called a concession. Quick on the heels of the British came sizable populations of Americans, French and Russians. The Treaty of the Bogue signed in 1843, and the Sino-American Treaty of Wanghia signed in 1844 forced Chinese to accept European and American demands to carry out trade on Chinese soil. Britain, France, and the United States all created area outside the walled city of Shanghai, which was still ruled by the Chinese. The Chinese-held old city of Shanghai fell to the rebels of the Small Swords Society in 1853 but was recovered by the Qing in February 1855. In 1854, the Shanghai Municipal Council was created to manage the foreign settlements. David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “In the middle of the 19th century, the Yangtze carried trade in tea, silk and ceramics, but the hottest commodity was opium.... It was a lucrative franchise: about one in ten Chinese was addicted to the drug. Opium attracted a multitude of adventurers. American merchants began arriving in 1844; French, German and Japanese traders soon followed. Chinese residents’ resentment of the Qing dynasty’s weakness, stoked partially by the foreigners’ privileged position, led to rebellions in 1853 and 1860. But the principal effect of the revolts was to drive half a million Chinese refugees into Shanghai; even the International Settlement, the zone where Westerners stayed, had a Chinese majority. By 1857 the opium business had grown fourfold. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

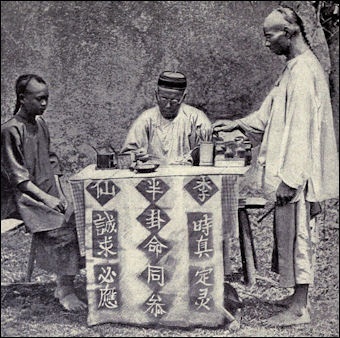

Shanghai Concessions

street fortuneteller

Shanghai became the focal point of European intervention into China. The former weaving and fishing town was carved up into separate and autonomous European districts known as concessions. Beyond the reach of Chinese laws and taxes, the concessions were self contained worlds with their prisons, police, courts, schools, barracks and hospitals. In addition to this, Shanghai had exclusive parks and gentlemen's clubs that Chinese were not allowed in. Many business were started by former opium traders. Some American enterprises claimed they sold everything.

By the 1850s, Shanghai had a community of 60,000 expatriates, most of whom lived in separate concessions which were divided along national lines. Between 1860–1862, the Taiping rebels twice attacked Shanghai and destroyed the city's eastern and southern suburbs, but failed to take the city. In 1863, the British and Americans merged their territory into the International Concession. The French opted out of the Shanghai Municipal Council and maintained its own concession to the south and southwest.

Devoss wrote: “The robust economy brought little cohesion to Shanghai’s ethnic mix. The original walled part of the city remained Chinese. French residents formed their own concession and filled it with bistros and boulangeries. And the International Settlement remained an English-speaking oligarchy centered on a municipal racecourse, emporiums along Nanjing Road and Tudor and Edwardian mansions on Bubbling Well Road. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

See Separate Article OLD SHANGHAI SIGHTS: THE BUND, CONCESSIONS AND COLONIAL-ERA BUILDINGS factsanddetails.com

Shanghai's Expatriate Community

Citizens of many countries and many walks of life came to Shanghai to live and work. Those who stayed for long periods –– some for generations –– called themselves "Shanghailanders". Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: In Shanghai, “a century ago, foreigners unpacked a whole new fascinating way of life on the docks here. From Western ships came bicycles, engine parts and young Chinese with a vision of modernity.” In the homes of rich Chinese, Shanghai's finest wore Western dress, listened to Western music wedding guests and Chinese-style squat toilets in the marital home, only the best sit-down contraptions imported from America.[Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 11, 2012]

In the 1920s and 1930s, almost 20,000 White Russians and Russian Jews fled the newly established Soviet Union and took up residence in Shanghai. These Shanghai Russians constituted the second-largest foreign community. Many of them were white Russian aristocrats that came to China after the Bolshevik Revolution in the 1920s and 30s and most of them arrived on the Trans-Siberian railroad. Many of them supported themselves with jewels they carried with them from Russia. Some lived in lavish villas but most were poor. For a time there were more white Russians than French in the French Concession.[Source: Wikipedia]

By the 1920s Shanghai had a expatriate community of 60,000. Most of foreigners were British but there were also sizable populations of Americans, French and Russians. Between World Wars I and II tens of thousands of European refugees fleeing Bolshevism and Nazism and equally large numbers of Chinese refugees fleeing civil strife and the Japanese invasion flooded into Shanghai. By 1932, Shanghai had become the world's fifth largest city and home to 70,000 foreigners. In the 1930s, some 30,000 Jewish refugees from Europe arrived in the city.

Other groups included turbanned Sikhs from India brought in by the British to direct traffic and patrol the streets in the International Settlement; Vietnamese troops brought in by the French to keep order in their concession; and America marines, British Tommies, French marines and Japanese Bluejackets brought into protect Shanghai from possible Chinese aggression.

At this time a lot of missionairies also poured into China. Many Olympic and Western sports first came to China via missionaries. In the 19th and 20th century Protestant missionaries abroad emphasized the gospel of sport nearly as much as the Gospels themselves.

Chinese in Shanghai

coolies

Some 200,000 Chinese workers helped turn Shanghai into the largest manufacturing city in Asia. Even in the foreign concessions about 90 percent of the residents were Chinese, the vast majority of them workers. Many of these "workers" were 12- and 13-year-old boys and girls who worked 13 hour days, chained to the machines, in slave-like conditions, unable to leave their heavily guarded factory compounds.

The Cantonese term for Europeans and Americans is gweilo, which literally translates to "devil man" but is often translated as "foreign devil." [Gweilo doesn’t really mean “foreign devils” at all though it is often translated that way. Gwei certainly can be translated as devil(s), but “lo” is just a rather familiar term for a person. “devil man” would be better. ] At the end of the 19th century the poet Yen-shi wrote:

Last year we called him the Foreign Devil

Now we call him "Mr. Foreigner, Sir!"

We weep over the departed but smile when a new wife takes her place

Ah, the affairs of the world are like the turning of a wheel

The Chinese in Shanghai also endured opium addiction, starvation, and exploitation by pimps and gangsters. The term "shanghaied" originated with the practice of kidnaping Chinese peasants and drunken drifters to provide cheap labor in foreign countries or to work on undermanned ships. The Chinese word ‘shanghai’, meaning to ruin someone (origin of the loan into English) has nothing to do with the word for the place Shanghai, both characters are written differently and one is in a different tone as well.

It has often been printed that there was sign in front of Huangpu Park in the British quarter that read "No admittance to Dogs and Chinese." Research has shown that this is a myth. There were rules about dogs and there were rules restricting Chinese servants but they were never placed together on the same sign. Nicholas Tapp of Australian National University, “The “dogs and Chinese placard “is a famous canard and it has been disproved that there was ever such a sign. Richard Hughes, for many years editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, said there were a number of regulations about the parks (including Huangpu) including one that the parks were reserved for Europeans, another that no dogs or bicycles were allowed. These were in Chinese, not English. Lynn Pan (famous author on Shanghai and overseas Chinese who lives here) denied that the sign has ever existed, though she said she had seen in a museum hundreds of propaganda replica signs like this produced by the Party for propaganda purposes in the 1960s. There is a conclusive article in the China Quarterly (142. 1995) which goes into the whole history of how the false juxtaposition was spread. The regulations altered in 1903 and 1928. At one point they said only Chinese who attended as servants were admitted. At another point dogs on leads were admitted. And so on. But the shocking juxtaposition which is so horrific, and in English, and as a publically displayed sign, is just a common misapprehension. There were rules about both of these things, but along with many other rules, and not jammed together in this shocking way.” [Source: Nicholas Tapp, Australian National University]

European Shanghai in the Early 20th Century

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “In the beginning it was a foreign dream, a Western treaty port trading opium for tea and silk. The muscular buildings along the riverfront known as the Bund (a word derived from Hindi) projected foreign, not Chinese, power. From around the world came waves of immigrants, creating an exotic stew of British bankers and Russian dancing girls, American missionaries and French socialites, Jewish refugees and turbaned Sikh security guards. To serve the international community and seek their own fortune many Chinese moved to Shanghai. A busy harbor carried out about half of China's foreign commerce. Goods from the interior of China came via the Yangtze River. Suzhou Creek linked Shanghai to the Grand Canal. Railways were built that linked Shanghai to Beijing and other parts of China and the world. “ [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

“The whole enterprise, however, rested on the several million Chinese immigrants who flooded the city, many of them refugees and reformers fleeing violent campaigns in the countryside, beginning in the mid-1800s with the bloody Taiping Rebellion. The new arrivals found protection in Shanghai and set to work as merchants and middlemen, coolies and gangsters. For all the hardships, these migrants forged the country's first modern urban identity, leaving behind an inland empire that was still deeply agrarian. Family traditions may have remained Confucian, but the dress was Western and the system unabashedly capitalist, and the favorite soup, borscht, came from Russians escaping the Bolsheviks. "We've always been accused of worshipping foreigners," says Shen Hongfei, one of Shanghai's leading cultural critics. "But taking foreign ideas and making them our own made us the most advanced place in China."”

David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “While the rest of the world suffered through the Great Depression, Shanghai—then the world’s fifth-largest city—sailed blissfully along. “The decade from 1927 to 1937 was Shanghai’s first golden age,” says Xiong Yuezhi, a history professor at Fudan University in the city and editor of the 15-volume Comprehensive History of Shanghai. “You could do anything in Shanghai as long as you paid protection [money].” In 1935 Fortune magazine noted, “If, at any time during the Coolidge prosperity, you had taken your money out of American stocks and transferred it to Shanghai in the form of real estate investments, you would have trebled it in seven years.” [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

Decadence in Early 20th Century European Shanghai

Known as both the "Whore of Asia" and the "Paris of Asia," late 19th-century and early 20th-century Shanghai boasted fine restaurants, exquisite craft shops, backstreet opium dens, several hundred ballrooms, gambling parlors and brothels with names like "Galaxy of the Beauties" and "Happiness Concentrated." Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “It was like no other place on Earth: a mixed-blood metropolis with a reputation for easy money---and easier morals. The British, French, and Americans built gracious homes along tree-lined streets. Local shops carried the latest fashions and luxuries. The racecourse dominated the center of town, while the city's nightlife offered everything from dance halls and social clubs to opium dens and brothels.

In the 1920s, foreigners played polo and enjoyed dog racing and horse racing. By the 1930s, Shanghai was the largest trading center in Asia, among the ten largest cities in the world, arguably the most decadent place on the planet, and a city so westernized, it had its own Chinatown. By some counts one in 20 women worked as prostitutes and Western taipans and Chinese compradores amassed huge fortunes, engaged in intrigues and plots and threw lavish parties.

The French licensed prostitution and opium smoking. At the height of Shanghai's age of debauchery it was possible to get room service heroin, buy 12-year-old female slaves, and find gangsters that worked for the police. One of the city's biggest attraction was the Great World Amusement Center, which featured prostitutes, freak shows, earwax extractors, face readers, kung fu masters, and love offices.

Old Shanghai was famous for its sing-song girls and ladies of the night. In the 1920s, an estimated 30,000 prostitutes were at work in Shanghai on any given night. One missionary described Shanghai as "an apology by God to Sodom and Gomorrah" and another called it "the Whore of the Orient." Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Shanghai was known for vice: not only opium, but also gambling and prostitution. Little changed after Sun Yat-sen’s Republic of China supplanted the Qing dynasty in 1912. The Great World Amusement Center, a six-story complex packed with marriage brokers, magicians, earwax extractors, love-letter writers and casinos, was a favorite target of missionaries. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

There was increasing politicization of the city's cabaret culture during the war years when the city was occupied by the Japanese military, as well as the abolition and eventual demise of the city's cabaret industry under the governments of the Chinese Nationalists in the late 1940s and the Communists in the 1950s. During the “dancers' uprising” (wuchao) of 1948 when thousands of cabaret workers in the city organized a violent protest against the government's “ban on dancing” (jinwu). When the Kuomintang took over Shanghai, they imposed a 10:00pm curfew. When the Communists claimed the city in 1949, they had no problem cleaning it up. They simply marched in and told the addicts and prostitutes they had the choice of cleaning up their act or being shot.

See Separate Article FOREIGNERS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com

Great World Amusement Center

Great World Amusement Center (south of People’s Square, Metro Line 8, Dashijie Station, Metro Lines 1, 2 and 8, People's Square Station) was once a six-story adult entertainment complex with gambling halls, opium dens, brothels, singsong girls, acrobats, magicians, and slot machines. The prostitutes wore increasingly skimpier outfits he higher one climbed. and there was special place on the roof where gamblers who had lost everything could leap to their death. For a while the building was the home of the Shanghai Youth Palace and a Guinness book of records display. .

Opium smoking in Shanghai

Great World, its modern incarnation, is an amusement arcade and entertainment complex originally built in 1917 on the corner of Avenue Edward VII (now Yan'an Road) and Yu Ya Ching Road (now Middle Xizang Road). It was the first and for a long time the most popular indoor amusement arcade in Shanghai and was called the “No. 1 Entertainment Venue in the Far East.” Some traditional styles of entertainment remain but it is main occupied today by modern forms of entertainment and electronic media as well as shops, souvenir stands, food stalls,. The facility was closed in 2003 during the SARS outbreak and reopened at its centennial after repairs, in March 2017. [Source: Wikipedia]

Founded by Shanghai magnate Huang Chujiu, The Great World was built as an integrated entertainment complex featuring amusement arcades, parlour games, music hall shows, variety shows and traditional Chinese theatre. It was rebuilt in 1928 in an eclectic style borrowing largely from European baroque, topped by a distinctive four-storey tower which quickly became a landmark.

On his visit in the mid-1930s, Hollywood film director Josef von Sternberg wrote: "On the first floor were gaming tables, singsong girls, magicians, pick-pockets, slot machines, fireworks, birdcages, fans, stick incense, acrobats, and ginger. One flight up were… actors, crickets and cages, pimps, midwives, barbers, and earwax extractors. The third floor had jugglers, herb medicines, ice cream parlors, a new bevy of girls, their high collared gowns slit to reveal their hips, and (as a) novelty, several rows of exposed (Western) toilets. The fourth floor had shooting galleries, fan-tan tables, … massage benches, … dried fish and intestines, and dance platforms. The fifth floor featured girls with dresses slit to the armpits, a stuffed whale, storytellers, balloons, peep shows, masks, a mirror maze, two love letter booths with scribes who guaranteed results, rubber goods, and a temple filled with ferocious gods and joss sticks. On the top floor and roof of that house of multiple joys a jumble of tightrope walkers slithered back and forth, and there were seesaws, Chinese checkers, mahjongg, … firecrackers, lottery tickets, and marriage brokers." Von Sternberg returned to Los Angeles and made "Shanghai Express" with Marlene Dietrich, whose character hisses: “It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.” Dietrich and von Sternberg also made the film Blue Angel together.

On August 14, 1937, it was the site of the Great World bombing, or "Black Saturday". During the second day of the Battle of Shanghai between Chinese and Japanese force, Great World opened its doors to refugees fleeing the fighting and then was accidently struck by two bombs from a damaged Republic of China Air Force bomber that trying to release the release the bombs into the largely- uninhabited nearby Shanghai Race Course, but released the bombs too early. About 2,000 people were killed or injured. After the Communist takeover of Shanghai in 1949, Great World was renamed "People's Amusement Arcade", but reverted to the old name in 1958. Closed during the Cultural Revolution, in 1974 the site became the "Shanghai Youth Palace". In 1981, Great World was re-opened as the "Great World Entertainment Centre".

The Great World consists of three four-storey buildings and two annexe buildings. The basic layout of the complex has remained the same since 1928 rebuilding. While the entertainment options have been updated over the years — with motion pictures, for example, being replaced by karaokes — many features remain the same. One legendary feature is the twelve distorting "magic mirrors" imported from the Netherlands that have amused visitors for more than a century. There is also a theater, music hall, Guinness hall, movie hall, video hall, magic world, dancing hall, KTV, tea house, ski field, the new Shanghai flavor snack corridor, restaurant and boutique market. Throughout the day there one can enjoy entertainment, performances, viewing, food and games.

See Separate Article OLD SHANGHAI SIGHTS: THE BUND, CONCESSIONS AND COLONIAL-ERA BUILDINGS factsanddetails.com

Shanghai in the 1920s

Shanghai in the 1920s and 30s

Shanghai had a veneer of foreign sophistication in the '30s," journalist Paul French wrote, "when Noel Coward sat in the Cathay Hotel writing Private Lives and partying with Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin at Victor Sassoon's mixed-sex (in the sense of mixed-up-sex) fancy dress parties. The city was then the world's third largest financial center, rich and exotic, and London and New York were a long way away. [Source: Paul French, Foreign journalists in China, from the Opium Wars to Mao ]

Carroll Alcott was one of the most well-known journalists. He to moved to Shanghai in 1928 and broke some good stories, notably about the opium business, German gunrunners and Japanese aggression in China; and he had once famously dined with a warlord in Yantai while the blood of his recently executed enemies dripped from the floor above into his noodles and shredded beef. Alfred Meyer, the managing editor of the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury had snapped him up to cover the Shanghai crime beat, a job Alcott revelled in, noting that a typical day involved as many as three murder trials, a gang shooting, half a dozen armed robberies, a jewel theft, and a couple of kidnappings.

Nightlife centered around Chinese cabarets and dance halls called wuting . A good book on the subject is Shanghai's Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919-1954 by Andrew Field. On the book Field wrote: “ The first five chapters recount the emergence and flourishing of Shanghai's “dancing world” (wujie, wuguo) including chapters on the role of Westerners in introducing Jazz Age dance and music culture to China, the first Chinese cabarets to operate in Shanghai during the 1920s, the design and construction of cabarets and nightclubs in the 1930s, the role of Chinese “dance hostesses” (wunu) in popularizing and facilitating the Jazz Age in China, and Chinese ballroom patrons and the political culture of Chinese nationalism.

Great figures from Shanghai in its heydays in the 1930s and 1940s include of Jazz Age moguls and gangsters, left and right wing politicians, and contemporary investors and writers. Great figures from Shanghai cinema include the great actress Shangguan Yunzhu, revered director Fei Mu. The prominence of Taiwanese and Hong Kong figures like director Hou Hsiao-hsien and singer/actress Rebecca Pang illustrate how much of Shanghai's creative spirit migrated to Taipei and Hong Kong after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

David Moser wrote in The Anthill: “Shanghai nightlife in the 1920s and 30s included jazz as a part of the cultural mix. Dozens of African-American jazz musicians traveled by steamboat to China to seek gigs in the freewheeling international club scene. Buck Clayton, who later on would play trumpet with Count Basie, formed his first jazz band in Shanghai. And local Chinese musicians absorbed it all to create a form of jazz with Chinese characteristics, a hybrid of New York’s Tin Pan Alley and Shanghai pop songs.[Source: David Moser: The Anthill, January 2016]

See Separate Article POP MUSIC IN CHINA: FROM SHANGHAI JAZZ IN THE 1920s TO K-POP IN THE 2020s factsanddetails.com

Shanghai Gangsters and Big Shots

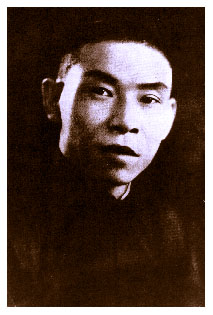

Du Yuesheng

Du Yuesheng One of Shanghai's most notorious figures was Shanghai Du Yuesheng ("Big-Eared Du"), a former sweet-potato vendor who started his life of crime as a policeman collecting protection money from local opium traders. As the head of the gang that controlled Shanghai's opium trade he reportedly funneled over $20 million a year to French authorities who allowed him to run his operation unhindered in the French Concession.

By the 1930s, Du had become so influential that Chiang Kai-shek put him in charge of the "Bureau of Opium Suppression." Never one to be too complacent he lived in a house with a secret trap door that could be used for quick getaways.

Huang Jinrong ("Pockmarked Huang") was another well-known Shanghai gangster. The gangster Zhanh Ziaolin was shot by his driver, who was believed to have been acting on orders from Chiang Kai-shek's secret police. In 1935 a total of 5,590 corpses were picked up off the streets

The warlord General "Dog Meat" Zhang Zong-chang (1880-1935) controlled Shanghai until he was ousted by Chiang Kai-shek. Known to Shanghai prostitutes as the "general with three long legs," Zhang reportedly once took on an entire brothel by himself, and said he owed his strength to his daily meals of black chow meat. People in Shanghai said he had "the physique of an elephant, the brain of a pig and the temperament of a tiger" and his nickname came from his fondness for game "throwing dog meat."

Sassoons and Kadoories

Another personality associated with Shanghai was Victor Sassoon, a Jewish businessman of British descent whose family was from Baghdad. He made millions trading opium, real estate and racing horses. His most famous quote was "there is only one race greater than the Jews and that's the Derby." His most famous possession was the Cathay Hotel, where the rich and famous wined and dined and Noel Coward wrote Private Lives. The Kadoories were another famous Shanghai-based family

Alex Smith wrote for Sup China: “The Sassoons were “once known, due to their wealth and influence, as “the Rothschilds of Asia” — a term the Sassoons themselves considered somewhat of an insult, since the Rothschilds were mere nouveau riche — and the Kadoories, depicted as the Sassoons’ less connected but determined distant cousins. “Forced to flee a Baghdad that was increasingly hostile to Jews in the late 1820s, the Sassoons moved their business empire to British India. The Kadoories would eventually follow suit, hoping to gain employment from their distant relatives. Their respective pursuits of fortune and opportunity would eventually take branches of both families to Shanghai, a port city increasingly controlled by foreign powers desperate for access to trade with China.

Although the two families came to be incredibly wealthy and forged intimate ties with those occupying the highest echelons of British society, in the context of rising anti-Semitism, their Jewishness prevented them from perhaps ever truly belonging to it (and in many ways, there is an unusual subalternness to these otherwise wealthy elites — the two families never really appear to wholly belong anywhere). In fact, despite having a British wife and children, Elly Kadoorie was repeatedly barred from acquiring British citizenship and, for a long stretch of time, was effectively stateless. The Kadoories would spend the last years of Elly’s life imprisoned by the Japanese in Shanghai’s Chapei internment camp.

Book: ‘The Last Kings of Shanghai’by Jonathan Kaufman, Viking, 2020]

Sassoons and Kadoories Businesses and Wealth

Victor Sassoon

Alex Smith wrote for Sup China: “With their direct links to opium production in India, the Sassoons were quick to find success in China by securing a monopoly on the country’s opium trade. While Britain’s agreement to curb and eventually cease Indian opium exports to China in 1907 dealt the Sassoons a solid blow, the family’s investments across textiles, ports, banking, and perhaps most notably, Victor Sassoon’s investments in Shanghai real estate, including the Cathay Hotel (now the Fairmont Peace Hotel), solidified their place among the world’s elite. [Source: Alex Smith, Sup China, July 2, 2020]

“While wealth initially proved more elusive for Elly Kadoorie, who began apprenticing for the Sassoons as a 15-year-old in India and later in Hong Kong, the family would also come to amass a fortune. After cutting his teeth in the rubber stock trade, Elly established himself as a successful financier, made key investments in Hong Kong electricity company China Light and Power, and, along with his two sons, built luxury hotels and properties in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

“While Kaufman details the glitzy parties that brought together people from various nationalities hosted in the Cathay and the Kadoorie’s Majestic, he also notes from the beginning that both families, despite living in Shanghai across generations, remained grossly out of touch with the rest of Chinese society and were, in many ways, agents of British imperialism. Kaufman details the tactics the Sassoons employed to outcompete rivals in the opium trade, which wreaked havoc on the lives of many ordinary Chinese, and points out that while the Sassoons were well aware of the perils of opium, their actions never seemed to weigh on their moral conscience, or indeed prompt any self-reflection whatsoever. Even supposedly progressive members of the family, such as Rachel Sassoon Beer, who became the first female editor-in-chief of a British newspaper, took pains to defend the family’s role in the trade generations later. [Source: Alex Smith, Sup China, July 2, 2020]

“Similarly, Kaufman shows how both families’ luxurious hotels not only contributed to the physical Westernization of Shanghai’s landscape, but also stoked resentment among the local population over the increasing inequality between Chinese and foreigners. In one brief but powerful scene, L Xùn , now considered perhaps the founding figure of Chinese modern literature, was forced to walk up seven floors of the Cathay Hotel to visit a British friend after being ignored by the elevator operator. And while this resentment and the subsequent communist movement would ultimately lead to the demise of both families’ Shanghai fortunes and the end of their time on the mainland, Kaufman avoids giving it his full attention. In fact, Chinese citizens only appear in the book as peripheral characters, something Kaufman acknowledges in the preface and justifies on the basis that this itself reflects just how removed these families were from their Chinese peers.

Jews in Shanghai

Shanghai also had a fairly large Jewish community in the early 20th century. Some were Russian Jews fleeing Russian pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Others came from other spots around the globe. Sephardic Jewish families like the Sassoons and Kadoories had been in Shanghai since the mid-19th century and made a fortune trading tea, opium and silk. During World War II, around 30,000 Jews fleeing Hitler found safe haven in the open port of Shanghai, where they built synagogues, Yiddish theaters and yeshivas even as the occupying Japanese forced many to live in a cramped ghetto.

Alex Smith wrote for Sup China: The Sassoons and Kadoories played key roles in establishing Shanghai as a temporary refuge for some 18,000 Jews fleeing Europe. “Kaufman depicts how despite their rival hotel empires, the Sassoons and the Kadoories worked together to convince the Nazi-aligned Japanese authorities, who controlled much of the city, not to expel the new arrivals, who at this point were arriving in the hundreds every week, and to treat them on a par with the city’s other foreign nationals. Victor Sassoon, Elly Kadoorie, and his son, Horace, provided housing, schooling, and food to refugee families, with Victor opening up one of his luxury skyscrapers to serve as a reception center for new arrivals while a kitchen in the building’s basement provided them with thousands of meals each day, and rallied high-profile Chinese intellectuals and politicians to protest the German government’s anti-Jewish policies. One family even recalled spotting a German sign as their boat arrived in Shanghai that read: “Welcome to Shanghai. You are no longer Jews but citizens of the world. All Shanghai welcomes you.” [Source: Alex Smith, Sup China, July 2, 2020]

Virtually nothing remains of the Shanghai's old Jewish community. In 1958, the government relocated all foreign graves---including the Jewish ones — to one international cemetery, which was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, when locals plundered the gravestones to use in construction. The last synagogues were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. About 200 Jews remain in Shanghai's Jewish enclave along with European-style row houses, a theater, a synagogue and several grand buildings. About 2,000 expatriate Jews live in Shanghai today. Most are entrepreneurs or corporate executives — or members of their family — from around the world.

See Separate Articles JEWS IN CHINA: THEIR HISTORY, COMMUNITIES AND HELPING THEM IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com JEWS AND JEWISH CULTURE IN CHINA TODAY factsanddetails.com ; OLD SHANGHAI SIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Chinese Communists Get Their Start in Shanghai

Carrie Gracie of the BBC wrote: “The founding congress of the Chinese Communist Party took place at a Shanghai girls' boarding school in 1921. At the time, they can hardly have imagined that they were men of destiny. They had to present themselves as a student group on vacation - and run away when the police came. But these rebels ended up running China, they do not need to dwell on the miraculous good luck which brought them to power in 1949." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, 10 17, 2012]

The Chinese Communist Party was formed in Shanghai in July — maybe July 21 — 1921. Among the 12 delegates at the first Communist Congress was Mao Zedong. In China, the event is known as the "First Supper," and nobody is really sure who else was there, when exactly it took place and what happened. Fearing a raid by French police, the meeting was adjourned after a short time and continued later on a houseboat on the Grand Canal near the town of Jiazing.

The main discussion point during the July 1921 meeting, it is said, was whether or not to break ties completely with bourgeois society or form a tactical alliance with merchants and landlords. Ignoring recommendations by two Communist International advisers from Moscow, the Chinese delegates decided to take a radical approach and have nothing to do with capitalism and demand the immediate surrender of land and machinery.

Other pioneering members of the fledgling Communist movement in Shanghai included Zhou Enlai, Chang Kuo-tao, and Deng Xiaoping. Fearing detection and massacre by the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek, the early Chinese Communists met in safe houses in Shanghai. Eventually they were forced out of Shanghai by a joint force of Kuomintang Nationalists and Shanghai gangsters.

By the late 1920s, David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Communists were sparring with the nationalist Kuomintang for control of the city, and the Kuomintang allied themselves with a criminal syndicate called the Green Gang. The enmity between the two sides was so bitter they did not unite even to fight the Japanese when long-running tensions led to open warfare in 1937. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

See Separate Article EARLY COMMUNISTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Shanghai Coup: Chiang Kai-shek Cracks Down on the Communists

The Communist Party's main rival and enemy in its early years was the Kuomintang, (Guomindang or KMT — the National People's Party, frequently referred to as the Nationalist Party) taken over by Chiang Kai-shek in the 1920s. For a while the Communist Party and the Kuomintang were allies.

As the Kuomintang proceeded with the military campaign to unite China — the Northern Expedition — in 1927,Chiang Kai-shek split with the Communist Party and ordered the assassination of Communist Party members. In 1927, shortly after he took control of the Kuomintang, Chiang shocked his Soviet Union allies by purging all Communists from the Kuomintang. He ordered all the Russian advisors to return home, he said, because the Chinese Communists had allegedly plotted to seize the leadership of the Kuomintang.

In March 1927, Chiang Kai-shek organized a reign of terror in Shanghai against the Communists, who at that time were still allied with the Kuomintang. Financed and armed with modern rifles and armored cars provided by the International Settlement, rich Shanghai businessmen and Shanghai's most powerful gang leaders, thousands of Kuomintang thugs and hundreds of gangsters were ordered by Chiang to kill every Communist they could find. Anti-Communist warlord Zhang Zoulin ordered a raid of the Soviet embassy in Beijing, arresting and executing 30 Communist activists who sought refuge there including Li Dazhou, a founder of the Chinese Communist Party. It was one of the few times in history the sancutary status of an embassy was breached,

In what later became known as the Shanghai Coup, between 5,000 and 10,000 workers, Communists and left-wing Kuomintang members were massacred. Zhou Enlai barely escaped. Communist Party founder Li Dazhao was killed by slow strangulation. Attacks were then mounted by the Kuomintang against the Communist in Canton, Changsa and Nanjing. The martyred revolutionary hero Wang Xiaohe was killed. Newspaper photos of him minutes before he was executed, showed him with his head held high smiling. All this drove the main Communist Party leadership underground in Shanghai. Other Communists were forced to set up their operations in the countryside in places like the caves around Guilin and Vieng Xai.

Shanghai, Japan and World War II

Japanese attack in 1937

The Sino-Japanese War in 1894 concluded with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which elevated Japan to become another foreign power in Shanghai. Japan built the first factories in Shanghai, which were soon copied by other foreign powers. Shanghai was then the most important financial center in the Far East. Under the Republic of China (1911–1949), Shanghai became a municipality with the foreign concessions excluded from its control. Headed by a Chinese mayor and municipal council, the new city governments created a new city-center in Jiangwan town of Yangpu district, outside the boundaries of the foreign concessions. This new city-center was planned to include a public museum, library, sports stadium, and city hall. [Source: Wikipedia]

In early 1932, in what is known as the January 28th Incident, a Shanghai mob attacked five Japanese Buddhist monks, leaving one dead. In response, the Japanese bombed the city and killed tens of thousands, despite Shanghai authorities agreeing to apologize, arrest the perpetrators, dissolve all anti-Japanese organizations, pay compensation, and end anti-Japanese agitation or face military action. The Chinese fought back fighting to a standstill; a ceasefire was brokered in May 1932.

In August 1937, the Japanese invaded Shanghai and easily defeated the Chinese Nationalist Army there is a little over three months. Describing the Battle for Shanghai, the Washington Post reported: "Fresh regiments of veteran Japanese regular army troops smashed China's defense line on the northern edge of the Yangtzepoo area of the International Settlement...Nipponese infantrymen fought with their bayonet behind a curtain of artillery shells and aerial bombs. There were continuous explosions of large-caliber artillery shells as Chinese and Japanese batteries engaged in a deafening duel." After the invasion of Shanghai Japanese troops conquered city after city. In November 1937, Shanghai was captured; the infamous Rape of Nanking took place in December 1937.

On August 14, 1937, the Great World Amusement Center was the site of the Great World bombing, or "Black Saturday". During the second day of the Battle of Shanghai between Chinese and Japanese force, Great World opened its doors to refugees fleeing the fighting and then was accidently struck by two bombs from a damaged Republic of China Air Force bomber that trying to release the release the bombs into the largely- uninhabited nearby Shanghai Race Course, but released the bombs too early. About 2,000 people were killed or injured.

The Japanese occupied Shanghai from 1937 to 1945. In that time, Shanghai was the only city in the world that did not require a visa and was sort like Asia's answer to the Casablanca, attracting thousands of displaced people, from all over the world, including Jews fleeing Nazi Germany.

Shanghai Under the Communists

In May 1949, the People's Liberation Army took control of Shanghai,. After the Communist takeover about 2 million people from the countryside moved into Shanghai. There was not enough jobs, food or housing for them so the government shipped about a million of them to farms, public works projects and industrial zones. "China's socialist overlords" Larmer wrote, "made Shanghai suffer for its role as a modern-day Babylon. Besides compelling the economic elite to leave and suppressing the local dialect, Beijing siphoned off almost all the city's revenues.

The Communists changed Shanghai dramatically. Boundaries and subdivisions were chnaged Addicts and prostitutes were given the choice of cleaning up their act or being shot. Trade collapsed. Businesses fled — many to Hong Kong — or were taken over. The government made Shanghai into a manufacturing center for textiles, steel, heavy machinery, ships and oil refining During the 1950s and 1960s, Shanghai became an industrial center and center for radical leftism. Jiang Qing — Mao’s wife — and the Gang of Four were from the city.

David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Once Mao Zedong and his Communists came to power in 1949, he and the leadership allowed Shanghai capitalism to limp along for almost a decade, confident that socialism would displace it. When it didn’t, Mao appointed hard-line administrators who closed the city’s universities, excoriated intellectuals and sent thousands of students to work on communal farms. The bronze lions were removed from the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, and atop the Customs House, Big Ching rang in the day with the People’s Republic anthem “The East Is Red.” The author Chen Danyan, 53, whose novel Nine Lives describes her childhood during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, remembers the day new textbooks were distributed in her literature class. “We were given pots full of mucilage made from rice flour and told to glue all the pages together that contained poetry,” she says. “Poetry was not considered revolutionary.” [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

Deng Reforms in Shanghai

Yet, even during the most tumultuous times of the Cultural Revolution, Shanghai was able to maintain high economic productivity and relative social stability. When China's economic reforms began in the 1980s, Shanghai had to wait nearly a decade to join in. "We kept wondering, When is it going to be our turn?" Huang Mengqi, a fashion designer and entrepreneur who owns a shop off the Bund, told National Geographic. In 1991 Deng Xiaoping finally allowed Shanghai to initiate economic reform, starting the massive development still seen today and the birth of Lujiazui in Pudong. Between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, Shanghai went from being a drab socialist city into a modern capitalist metropolis. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““I first visited Shanghai in 1979, three years after the Cultural Revolution ended. China’s new leader, Deng Xiao―ping, had opened the country to Western tourism. My tour group’s first destination was a locomotive factory. As our bus rolled along streets filled with people wearing Mao jackets and riding Flying Pigeon bicycles, we could see grime on the mansions and bamboo laundry poles festooning the balconies of apartments that had been divided and then subdivided. Our hotel had no city map or concierge, so I consulted a 1937 guidebook, which recommended the Grand Marnier soufflé at Chez Revere, a French restaurant nearby. Chez Revere had changed its name to the Red House, but the elderly maitre d’ boasted that it still served the best Grand Marnier soufflé in Shanghai. When I ordered it, there was an awkward pause, followed by a look of Gallic chagrin. “We will prepare the soufflé,” he sighed, “but Monsieur must bring the Grand Marnier.” [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

“In 1994, China’s communist leaders were vowing to transform the city into “the head of the dragon” of new wealth by 2020. Now that projection seems a bit understated. Shanghai’s gross domestic product grew by at least 10 percent a year for more than a decade until 2008, the year economic crises broke out around the globe, and it has grown only slightly less robustly since. The city has become the engine driving China’s bursting-at-the-seams development, but it somehow seems even larger than that. As 19th-century London reflected the mercantile wealth of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, and 20th-century New York showcased the United States as commercial and cultural powerhouse, Shanghai seems poised to symbolize the 21st century.

Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and the Shanghai Gang

Jiang Zemin was China's leader from 1990 to 2003. He rose to power in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square killings, oversaw the handover of Hong Kong in 1997 and led his country at a time in which China became one of the world's most powerful economies. Zemin was plucked from obscurity in 1989 to head the Communist Party after the bloody crackdown on democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Jiang replaced Zhao Ziyang, who was toppled by hardliners for supporting the student movement at Tiananmen Square. According to the Washington Post" Deng Xiaoping hoped a clearer succession plan would add stability to the system; he appointed Jiang as his immediate successor and elevated Hu Jintao (President of China from 2002 to 2012) so that he could later take Jiang's place. Jiang built his camp of allies — called the “Shanghai gang” — drawing from his old base as the city's party chief.

Jiang was born into an educated family in Yangzhou City in Jiangsu in 1926 and got an engineering degree from Jiatong University in Shanghai in 1947. Jiang was made party chief (a position higher than mayor) in Shanghai in 1985 at time when Shanghai was regarded as breeding ground for party talent. Jiang won brownies points when he managed to defuse huge pro-democracy demonstrations in Shanghai around the time of Tiananmen Square without ordering the military to open fire. Instead he closed down the Economic Herald, a Shanghai newspaper that allegedly fanned unrest in Beijing, and convinced Shanghai students to go home peacefully. During a speech at Jiantong University he saw a poster quoting Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and surprised students by reciting passages from the address in English. In 1993, Jiang gave U.S. President Bill Clinton a Shanghai-made saxophone.

Jiang Zemin peaceful resolution of the demonstrations caught Deng's eye. Deng had just jettisoned the ultra liberal Zhao Ziyang and was looking for fresh blood but not one that rocked the boat too much. Jiang fit the bill. Within a matter a months he was brought to Beijing and promoted to the number 2 position in China in 1989. After Deng's death in February 1997, Jiang dismissed scores of civilian, military and security officials, including his main Politburo rival Qiao Shi, and filled the positions people who were loyal to him, many of them from his Shanghai Gang. The Shanghaiese were so well represented in the upper echelons of power people joked that Politburo meetings were conducted in the Shanghai dialect.

Zhu Rongji, the second most powerful man in China in the Jiang era, was also from Shanghai. In 1988, he was named the mayor of Shanghai and worked under Jiang, the city's party chief. Zhu made a name for himself leading a successful ant-corruption drive, attracting foreign investors, triggered a boom that continues today, and diffusing demonstrations during the Tiananmen Square crisis by appearing on television and making a direct appeal for calm. When Zhu was mayor of Shanghai He was nicknamed Mr. One Chop because of efforts to reduce the number of chops or signatures on permits and bureaucratic documents. His reputaion for propeiety was unblemished, Once a relative asked him to bend the rules to get him a Shanghai residency permit. Zhu replied, "What I can do, I have done already. What I cannot do, I will never do." He guided China into the World Trade Organization and allowed entrepreneurs into the party for the first time.

Jiang handed over his leadership roles to Hu Jintao, who was born in Shanghai, in 2002 and 2003. Hu Jintao was the president of China from 2003 to 2013. Hu Jintao was born in December 1942 into a merchant family from Anhui and was raised in Taizhou a small city in Jiangsu Province. Hu's first years in power were marked by making compromises with rivals and building a power base. By 2006 he was strong enough to oust his rivals and bring his loyalists onto positions of power, replacing 40 of the 62 top province level jobs that had been appointed by Jiang with his own people. He also carried out a major reshuffling at the 17th Party Congress in 2007. A pivotal move was the ousting of Chen Liangyu on corruption charges (See Chen Liangyu, Corruption). Chen was appointed by Jiang Zemin and was a leader of the so-called Shanghai Gang. Jiang had conducted a similar move 11 years before to oust rivals in Beijing.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.