OPIUM WARS

In 1839, Lin Tse-Hsu, the imperial Chinese commissioner in charge of suppressing the opium traffic in China, ordered all foreign traders to surrender their opium. In response, the British sent a group of warships to the coast of China, triggering the First Opium War, which the British won in 1841. Along with paying a large indemnity, the defeated Chinese ceded Hong Kong to the British. In 1856, hostilities towards China were renewed, this time by the British and French, resulting in the Second Opium War, which China again lost. After this China was forced to pay more indemnity and the importation of opium to China was legalized.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ “Western military weapons, including percussion lock muskets, heavy artillery, and paddlewheel gunboats, were far superior to China's. Britain's troops had recently been toughened in the Napoleonic wars, and Britain could muster garrisons, warships, and provisions from its nearby colonies in Southeast Asia and India.

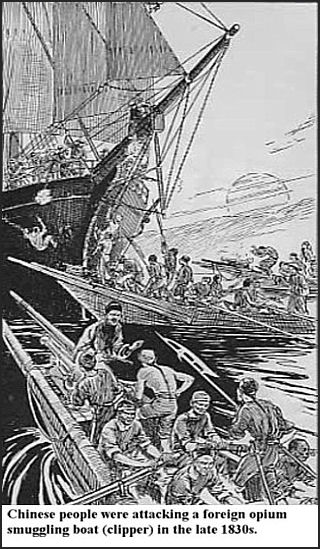

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “The first shots were fired when the Chinese objected to the British attacking one of their own merchant ships. The Royal Navy established a blockade around Pearl Bay to protest the restriction of free trade … in drugs. Two British ships carrying cotton sought to run the blockade in November 1839. When the Royal Navy fired a warning shot at the second, The Royal Saxon, the Chinese sent a squadron of war junks and fire-rafts to escort the merchant. HMS Volage's Captain, unwilling to tolerate the Chinese "intimidation," fired a broadside at the Chinese ships. HMS Hyacinth joined in. One of the Chinese ships exploded and three more were sunk. Their return fire wounded one British sailor. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016 ]

“Seven months later, a full-scale expeditionary force of 44 British ships launched an invasion of Canton. The British had steam ships, heavy cannon, Congreve rockets and infantry equipped with rifles capable of accurate long range fire. Chinese state troops — "bannermen" — were still equipped with matchlocks accurate only up to 50 yards and a rate of fire of one round per minute. Antiquated Chinese warships were swiftly destroyed by the Royal Navy. British ships sailed up the Zhujiang and Yangtze rivers, occupying Shanghai along the way and seizing tax-collection barges, strangling the Qing government's finances. Chinese armies suffered defeat after defeat.”

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu Opium Wars : Emperor of China’s War on Drugs Opioids.com Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinese History: Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com : OPIUM WARS PERIOD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FOREIGNERS AND CHINESE IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF CHINESE AMERICANS AND IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com ; TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com; BOXER REBELLION factsanddetails.com; EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com; PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China" by Julia Lovell (Picador, 2011) Amazon.com; “Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age”by Stephen R. Platt, Mark Deakins, et al. Amazon.com; "Opium Regimes, China, Britain and Japan, 1839-1952" edited by Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi Amazon.com; "Sea of Poppies" by Amitva Ghosh (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008) a novel set during the Opium Wars mostly in India but also in China Amazon.com; “The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty” by Haijian Mao, Joseph Lawson Amazon.com; “The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700–1845" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 11: Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911, Part 2" by John K. Fairbank and Kwang-Ching Liu Amazon.com; Amazon.com;

Opium Trade is Banned in China

Lin Zexu

Alarmed by the large amount of silver leaving the country, the Chinese Emperor banned the import of opium, but the edict was largely ignored by British and Chinese traders who had grown filthy rich from the trade and powerful enough to ignore the Emperor who rarely left the Forbidden Palace more than a 1,000 miles away from Canton in Beijing.

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “When the indecisive and harassed Emperor Daoguang, himself a user when young, came to the crumbling Qing throne in 1820, he attempted to stamp out a habit that was all but universal. He was ostensibly moved by anxieties about a balance of payments deficit and a shortage of silver, both blamed on the opium trade, but Lovell argues that the trade also became the scapegoat for the many ills and rebellions that beset the empire. “ [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, September 11, 2011]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The government debated about whether to legalize the drug through a government monopoly like that on salt, hoping to barter Chinese goods in return for opium. But since the Chinese were fully aware of the harms of addiction, in 1838 the emperor decided to send one of his most able officials, Lin Tse-hsu (Lin Zexu, 1785-1850), to Canton (Guangzhou) to do whatever necessary to end the traffic forever. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Efforts By China to Clamp Down on the Opium Trade

In December 1838, after years of debate and ineffective action, the emperor appointed Lin Zexu as commissioner in Canton with instructions to stamp out the opium trade. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““Lin was able to put his first two proposals into effect easily. Addicts were rounded up, forcibly treated, and taken off the habit, and domestic drug dealers were harshly punished. His third objective — to confiscate foreign stores and force foreign merchants to sign pledges of good conduct, agreeing never to trade in opium and to be punished by Chinese law if ever found in violation — eventually brought war.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Within two months Lin had arrested hundreds and confiscated nearly 14 tonnes of opium. Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: Lin Zexu instituted arrested 1,700 dealers, and seized the crates of the drug already in Chinese harbors and even on ships at sea. He then had them all destroyed. That amounted to 2.6 million pounds of opium thrown into the ocean. Lin even wrote a poem apologizing to the sea gods for the pollution. Angry British traders got the British government to promise compensation for the lost drugs, but the treasury couldn't afford it. War would resolve the debt. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

Chinese officials in Canton staged an elaborate charade to convince the Emperor they were doing everything in their power to halt the opium trade. When the opium was carried by British ships up the Pearl River to Canton from Linton Island, where it was stored in warehouses, Chinese navy junks pursued the British ships, making a big racket, firing their cannons and banging their war gongs, but rarely did much of anything to actually halt the British ships.

Beginning of the First Opium War

destroying opium in Canton

The First Opium War (1839-42) began in March 1839, when Lin Zexu, ordered British merchants to stop trading opium "forever" and surrender "every article" of opium in their possession. The Chinese navy surrounded opium-carrying British ships near Canton, cutting off their food supply, while Lin prohibited all foreigners from leaving Canton, in effect holding them hostage, until the opium was turned over. [Source: Stanley Karnow, Smithsonian magazine]

The British held off the Chinese for six weeks until British naval officer Charles Elliot advised the British merchants to hand over their entire inventory of opium, some 20,000 chests (2.7 million pounds, about 95 percent British and 5 percent American), telling them that the British government promised to reimburse them at the going prices. The merchants were willing to go along with the offer, figuring they would get their money and that a shortage would only boost the demand and the price of the drug.

When Elliot agreed to hand over the 20,000 chests while assuring the merchants that the British crown would make good the losses, he transformed the dispute into an affair of state. Lin reported to the emperor that the matters were concluded satisfactorily. A few months later, somewhat to his surprise, the British gunboats arrived. [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, September 11, 2011]

Elliot may have told the drug lords that the British government promised to reimburse them, but Chinese sources say that this was trickery. Evidently after their opium had been burned, the drug lords said Lin told them they would be reimbursed, but Lin never said such a thing. This was a pretext for demanding further concessions.

Commissioner Lin ordered the confiscated opium placed into basins dug at Humen Beach where it was spoiled with lime and left to wash out to sea. When Lin confiscated the opium at Humen, water was poured on it, then salt, and then lime, which caused it to ignite, so in Chinese, Lin is remembered for burning the opium, not just washing it to sea. June 3 is Forbidding Drug Day.

Lin also sent a letter to 20-year-old Queen Victoria. Part of it read: "We have heard that in your honorable barbarian country the people are not permitted to inhale the drug. If it is admittedly so deleterious, how can seeking profit by exposing others to its malefic power be reconciled with the decrees of Heaven?"

First Opium War Fighting

In July 1840 a fleet of British warships approached the southern coast of China, intent on avenging a series of insults and injuries inflicted on British subjects over the preceding months. The first battle lasted nine minutes.

In July 1840 a fleet of British warships approached the southern coast of China, intent on avenging a series of insults and injuries inflicted on British subjects over the preceding months. The first battle lasted nine minutes.

Lin let the British leave Canton, and Elliot, fearing more trouble, evacuated the foreign citizens of Canton 90 miles away to a strait known as Hong Kong ("Fragrant Harbor"). Lin, who supported trade with the West, with the exception of opium, was worried the foreigners were going to leave for good. In an effort to force the British to return to Canton, he sent his navy to Hong Kong with orders to open fire if necessary to bring the foreigners back.

The British and Chinese ships faced off near Hong Kong. Within an hour the small contingent of Chinese ships routed the 29 Chinese junks. Lin told the Emperor that the Chinese nearly won and he was honored for his bravery.

The British used the seizure of the opium as an excuse to start a war against China. British pursued war for two main reasons: 1) British merchants and farmers growing the opium in India were making heaps of money; 2) and China was easier to exploit and subdue if large numbers of its citizens were under the influence of the drug.

Unprepared for war and grossly underestimating the capabilities of the enemy, the Chinese were disastrously defeated, and their image of their own imperial power was tarnished beyond repair. British reinforcements from India arrived in June 1840. British gunboats — iron-hulled steamships and powerful cannons — attacked coastal cities and laid waste to important Chinese fortresses. The British seized control of Canton and the surrounding areas, killing thousands. After British gunships stormed up the Yangtze River and the British threatened to attack Nanjing and Peking, China surrendered. Reduced to an opium-addicted shell China was defeated by a few British cannon.

Chinese Perception of the First Opium War

According to one Chinese pamphlet: "Humen was the place where the Chinese people captured and burned the opium dumped into China by British and American merchants in the 1830s and it was also the outpost of the Chinese people to fight against the aggressive opium war. In 1839, Lin Zexu, the then imperial envoy of the Qing government...forced the British and American opium mongers to hand over 20,285 cases of opium...and burned all of them at Humen Beach...This just action showed the strong will of the Chinese people to resists imperialist aggression..."

According to another Chinese pamphlet: "No sooner had the British invaders landed on the western outskirts of Guangzhou on May 24, 1841 than they started to burn, slaughter and loot the people. All this aroused Guangzhou people's great indignation...On May 39, they lured British troops to the place called Niulangang where they used hoes, swords and spears as weapons and annihilated over 200 British invaders armed with rifles and cannons."

To mark the 156th anniversary of the starting of the Opium War in 1995, Lin Zexu was honored with the burning of 368 pounds of heroin, opium and morphine confiscated in drug busts in the previous five months.

"Unequal Treaties" After the Opium War

The result of the First Opium War was a disaster for the Chinese. By the summer of 1842 British ships were victorious and were even preparing to shell the old capital, Nanking (Nanjing), in central China. The emperor therefore had no choice but to accept the British demands and sign a peace agreement. This agreement, the first of the "unequal treaties," opened China to the West and marked the beginning of Western exploitation of the nation. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

After the Chinese surrendered,the Treaty of Nanjing was signed on board a British warship by two Manchu imperial commissioners and the British plenipotentiary in August 1842. The first of several "unequal treaties," it that gave up the island Hong Kong to the British "in perpetuity," opened five ports to European trade, forced China to pay an indemnity of $21 million (around $500 million in today’s money and large sum for a largely impoverished country and bankrupt dynasty) and minimal tariffs on imported goods. It also forced China to continue accepting East India Company opium. The Qing Emperor at first refused to accept the Nanjing Treaty, but another British attack changed his mind. Further concessions were made after the second Opium War in 1860.

The Treaty of Nanjing also limited the tariff on trade to 5 percent ad valorem; granted British nationals extraterritoriality (exemption from Chinese laws). In addition, Britain was to have most-favored-nation treatment, that is, it would receive whatever trading concessions the Chinese granted other powers then or later. The Treaty of Nanjing set the scope and character of an unequal relationship for the ensuing century of what the Chinese would call "national humiliations." The treaty was followed by other incursions, wars, and treaties that granted new concessions and added new privileges for the foreigners.

One unequal treaty, which forced China to involuntarily open new "treaty ports" and pay further indemnities to European powers, was drawn up after China refused to apologize for a torn British flag. In the Convention of Peking in 1860 China opened up more ports to foreigners and paid more reparations and allowed British ships to carry indentured Chinese laborers (“coolies”) to the United States and legalized the opium trade.

Neither the Chinese emperor or Queen Victoria were happy about the outcome of the Opium War and the treaties. Elliot became the chargé d'affaires in the Republic of Texas and the Chinese official who negotiated the treaty was sent to Tibet.

Excerpts from The Treaty of Nanjing, August 1842

Article I: There shall henceforth be Peace and Friendship between … (England and China) and betweentheir respective Subjects, who shall enjoy full security and protection for their persons and property within the Dominions of the other. [Source: “From Changing China: Readings in the History of China from the Opium War to the Present, by J. Mason Gentzler (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1977); Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Article II: His Majesty the Emperor of China agrees that British Subjects, with their families and establishments, shall be allowed to reside, for the purpose of carrying on their commercial pursuits, without molestation or restraint at the Cities and Towns of Canton, Amoy, Foochowfu, Ningpo, and Shanghai, and Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain, etc., will appoint Superintendents or Consular Officers, to reside at each of the above.named Cities or Towns, to be the medium of communication between the Chinese Authorities and the said Merchants, and to see that the just Duties and other Dues of the Chinese Government as hereafter provided for, are duly discharged by Her Britannic Majesty’s Subjects.

Signing of Nanking Treaty

Article III: It being obviously necessary and desirable, that British Subjects should have some Port whereat they may careen and refit their Ships, when required, and keep Stores for that purpose, His Majesty the Emperor of China cedes to Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain, etc., the Island of Hong.Kong, to be possessed in perpetuity by her Britannic Majesty, Her Heirs and Successors, and to be governed by such Laws and Regulations as Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain, etc., shall see fit to direct.

Article V: The Government of China having compelled the British Merchants trading at Canton [Guangzhou] to deal exclusively with certain Chinese Merchants called Hong merchants (or Cohong) who had been licensed by the Chinese Government for that purpose, the Emperor of China agrees to abolish that practice in future at all Ports where British Merchants may reside, and to permit them to carry on their mercantile transactions with whatever persons they please, and His Imperial Majesty further agrees to pay to the British Government the sum of Three Millions of Dollars, on account of Debts due to British Subjects by some of the said Hong Merchants (or Cohong) who have become insolvent, and who owe very large sums of money to Subjects of Her Britannic Majesty.

Article VII: It is agreed that the Total amount of Twenty.one Millions of Dollars, described in the three preceding Articles, shall be paid as follows: Six Millions immediately. Six Millions in 1843 … Five Millions in 1844 … Four Millions in 1845 …

Article IX: The Emperor of China agrees to publish and promulgate, under his Imperial Sign Manual and Seal, a full and entire amnesty and act of indemnity, to all Subjects of China on account of their having resided under, or having had dealings and intercourse with, or having entered the Service of Her Britannic Majesty, or of Her Majesty’s Officers, and His Imperial Majesty further engages to release all Chinese Subjects who may be at this moment in confinement for similar reasons.

Article X: His Majesty the Emperor of China agrees to establish all the Ports which are by the 2nd Article of this Treaty to be thrown open for the resort of British Merchants, a fair and regular Tariff of Export and Import Customs and other Dues, which Tariff shall be publicly notified and promulgated for general information, and the Emperor further engages, that when British Merchandise shall have once paid at any of the said Ports the regulated Customs and Dues.

Background Behind the Second Opium War

At of the Second Opium War in the late 1850s and early 1860s, the Qing government was experiencing both internal and external pressures from the Taiping Army and the English and French troops.Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “Imperialism was on the upswing by the mid-1800s. France muscled into the treaty port business as well in 1843. The British soon wanted even more concessions from China — unrestricted trade at any port, embassies in Beijing and an end to bans on selling opium in the Chinese mainland. One tactic the British used to further their influence was registering the ships of Chinese traders they dealt with as British ships.[Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016 ]

“The pretext for the second Opium War is comical in its absurdity. In October 1856, Chinese authorities seized a former pirate ship, the Arrow, with a Chinese crew and with an expired British registration. The captain told British authorities that the Chinese police had taken down the flag of a British ship. The British demanded the Chinese governor release the crew. When only nine of the 14 returned, the British began a bombardment of the Chinese forts around Canton and eventually blasted open the city walls.

“British Liberals, under William Gladstone, were upset at the rapid escalation and protested fighting a new war for the sake of the opium trade in parliament. However, they lost seats in an election to the Tories under Lord Palmerston. He secured the support needed to prosecute the war. China was in no position to fight back, as it was then embroiled in the devastating Taiping Rebellion, a peasant uprising led by a failed civil-service examinee claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. The rebels had nearly seized Beijing and still controlled much of the country.

Dragoon Guards in the Second Opium War

Second Opium War

The Second Opium War began on October 8, 1856 after Chinese officials searching for pirates arrested the crew of the British ship Arrow. The war ended in 1858 after British troops occupied Tianjin and Beijing, and French and British gunboats bombarded Tianjin fortresses until the Chinese signed the Treaty of Tianjin (1858).

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “Once again, the Royal Navy demolished its Chinese opponents, sinking 23 junks in the opening engagement near Hong Kong and seizing Guangzhou. Over the next three years, British ships worked their way up the river, capturing several Chinese forts through a combination of naval bombardment and amphibious assault. France joined in the war — its excuse was the execution of a French missionary who had defied the ban on foreigners in Guangxi province. Even the United States became briefly involved after a Chinese fort took pot shots at long distance at an American ship. In the Battle of the Pearl River Forts, a U.S. Navy a force of three ships and 287 sailors and marines took four forts by storm, capturing 176 cannons and fighting off a counterattack of 3,000 Chinese infantry. The United States remained officially neutral.” [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

During the second opium war, Hong Kong baker Cheong Ah Lum was accused of putting arsenic into his bread and poisoning 300 people to get even for injustices against the Chinese. Cheong was acquitted on lack of evidence but was deported to China.

A second opium war culminated in 1860 with the looting and burning of the imperial pleasure grounds, the Yuan Ming Yuan, in the northwest suburbs of Beijing by British and French troops. After the burning of Yuan Ming Yuan (the Summer Palace), Emperor Xianfeng made an escape to the Rehe Mountain Resort, where he eventually died in July.

Earl of Elgin's entrance into Peking

Looting of the Summer Palace

In October 1860, after the Second Opium War officially ended, French and British troops went on the rampage and looted and burned down the Emperor's spectacular Summer Palace, known in Chinese as Yuanmingyuan ("Garden of Perfect Brightness"), near Beijing. Every schoolchild in China knows the story as a symbol of the humiliation exacted on China by the colonial powers. British-French forces razed the palace in retaliation for the execution of allied prisoners. After watching the looting of the Summer Palace, Captain Charles Gordon of the British army wrote, "You can scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the palaces we burnt."

Recounted in Chinese textbooks and in countless television dramas, the destruction of the Old Summer Palace, remains a crucial event epitomizing China’s fall from greatness. Begun in the early 18th century and expanded over the course of 150 years, the palace was a wonderland of artificial hills and lakes, and so many ornate wooden structures that it took 3,000 troops three days to burn them down. The wound is still open and hurts every time you probe it, said Liu Yang, a Beijing lawyer and a driving force in the movement to regain stolen antiquities. It reminds people what may come when we are too weak. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, December 12, 2009]

A number of antiquities and valuable pieces of art were stolen from the Summer Palace when it was razed by French and British troops. The most famous stolen antiquities are bronze animal heads, which date to 1750 and were part of a 12-animal water-clock fountain configured around the Chinese zodiac in the imperial gardens of the Summer Palace. As of the 2000s, seven of the 12 fountain pieces had been found; the whereabouts of the other five bronze heads are unknown. In March 2008, a big deal was made about the offering of a bronze rabbit’s head and a companion piece depicting a rat that were put up for sale at a Christies auction. The pieces had been stolen from the Summer Palace in 1860. They were owned by the late fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent.

Perceptions of the Opium Wars in China

Lord Palmerton, Britain's foreign secretary at the time of the war said, "It would be called the Opium War because opium was the article of commerce that had caused it. But the war would not be fought over opium but over trade, the urgent desire of a capitalist, industrial, progressive country to force a Confucian, agricultural and stagnant one to trade with it."

Looting of the Summer Palace

Chinese have been humiliated and shamed by the Opium War for 150 years. "Whether we are from Hong Kong, China or Taiwan, I believe our viewpoint is the same — that the Opium War was not a trade war but an act of expansionism or militarism on the part of the British," one Hong Kong publisher told the Los Angeles Times. "It is like the Japanese saying their action in World War II were not aggression. For many Chinese, the wrongs of the Opium Wars were not righted until Hong Kong was handed over in 1997.

The Opium Wars are often used to illustrate imperialism at its very worst. The British, wrote historian Jack Keegan, found they could force unwanted opium on China, create a demand and back it up with the force of arms. This "inevitably leads the seller into imposing his political will on an unwilling buyer, and soon becoming a imperialist.” [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “For the British, the opium war defined the Chinese as decadent orientals, caricatured in popular fiction in the early 20th century. Their influence lingers in recurrent racist stereotypes as China's rise sets western nerves on edge."

More Fighting and Further Humiliations After the Second Opium War

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “When foreign envoys drew up the next treaty in 1858 the terms, were even more crushing to the Qing Dynasty's authority. Ten more cities were designated as treaty ports, foreigners would have free access to the Yangtze river and the Chinese mainland, and Beijing would open embassies to England, France and Russia....Russia did not join in the fighting, but used the war to pressure China into ceding a large chunk of its northeastern territory, including the present-day city of Vladivostok. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

The Xianfeng Emperor at first agreed to the treaty, but then changed his mind, sending Mongolian general Sengge Rinchen to man the Taku Forts on the waterway leading to Beijing. The Chinese repelled a British attempt to take the forts by sea in June 1859, sinking four British ships. A year later, an overland assault by 11,000 British and 6,700 French troops succeeded. When a British diplomatic mission came to insist on adherence to the treaty, the Chinese took the envoy hostage, and tortured many in the delegation to death. The British High Commissioner of Chinese Affairs, Lord Elgar, decided to assert dominance and sent the army into Beijing. British and French rifles gunned down 10,000 charging Mongolian cavalrymen at the Battle of Eight Mile Bridge, leaving Beijing defenseless. Emperor Xianfeng fled. In order to wound the Emperor's "pride as well as his feeling" in the words of Lord Elgar, British and French troops looted and destroyed the historic Summer Palace.

“The new revised treaty imposed on China legalized both Christianity and opium, and added Tianjin — the major city close to Beijing — to the list of treaty ports. It allowed British ships to transport Chinese indentured laborers to the United States, and fined the Chinese government eight million silver dollars in indemnities. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “oreigners, especially missionaries, were allowed free movement and business anywhere in the country. Conflicts for the rest of the century wrung more humiliating concessions from China: with Russia over claims in China's far west and northeast in 1850 and 1860, with England over access to the upper reaches of the Yangtze River in 1876, with France over northern Vietnam in 1884, with Japan over its claims to Korea and northeast China in 1895, and with many foreign powers after 1897 which demanded "spheres of influence," especially for constructing railroads and mines. In 1900, an international army suppressed the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion in northern China, destroying much of Beijing in the process. Each of these defeats brought more foreign demands, greater indemnities that China had to repay, more foreign presence along the coast, and more foreign participation in China's political and economic life. Little wonder that many in China were worried by the century's end that China was being sliced up "like a melon."”

Signing of the Treaty of Tientsin

Legacy of the Opium Wars in China

The Opium Wars mark the beginning of modern Chinese history. They deeply undermined the Emperor's authority and set in motion a series of events that would eventually lead to the Qing Dynasty's collapse. They also brought about the decisive foreign occupation of China by foreign powers. The humiliating Treaty of Nanking forced China to expand trade opportunities and to cede territory to Britain.

To force the Chinese government to open China's doors for so-called “free trade”, other Western countries resorted to non-trade means, generally force, to achieve their goals. Consequently, China quickly fell from being a wealthy power to a semi-colonized country, and soon thereafter the economy almost totally collapsed while its market was flooded with goods and capital from the West. According to some historical data, in 1820, 20 years before the first Opium War, China's gross domestic product was 32.4 percent of the word figure, the richest country at that time. After 1842, foreign merchants were allowed to live in treaty ports governed by their own laws. The five treaty ports were Canton, Amoy (Xiamen), Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningbo (Ningpo) and Shanghai. In 1858 ten more ports were opened to trade. Four more were opened in 1876.

The seizure and maintenance of Hong Kong was a key step in the expansion of the opium business. After the Opium Wars, the opium trade, with official but secret government support, rebounded with a vengeance. By the 1860s, 2,000 opium-carrying British vessels docked in Hong Kong each year. Even though the exporting of opium from India to China was banned in 1913, the trade continued.

European powers were able to defeat the Chinese easily during the Opium Wars, and later during the Boxer Rebellion, because they had superior weapons and machines, especially the formidable British gun boats. Because Western military technology was far superior to their own, the Qing rulers had no choice but to kowtow to Britain and other European powers, who carved up spheres of influence and brought in troops to guard their territories, which not only included China but also Southeast Asia.

'Century of Humiliation' After the Opium Wars

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “It's hard to over-emphasize the impact of the Opium Wars on modern China. Domestically, it's led to the ultimate collapse of the centuries-old Qing Dynasty, and with it more than two millennia of dynastic rule. It convinced China that it had to modernize and industrialize. Today, the First Opium War is taught in Chinese schools as being the beginning of the "Century of Humiliation" — the end of that "century" coming in 1949 with the reunification of China under Mao. While Americans are routinely assured they are exceptional and the greatest country on Earth by their politicians, Chinese schools teach students that their country was humiliated by greedy and technologically superior Western imperialists. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

“The Opium Wars made it clear China had fallen gravely behind the West — not just militarily, but economically and politically. Every Chinese government since — even the ill-fated Qing Dynasty, which began the "Self-Strengthening Movement" after the Second Opium War — has made modernization an explicit goal, citing the need to catch up with the West. The Japanese, observing events in China, instituted the same discourse and modernized more rapidly than China did during the Meiji Restoration.

“Mainland Chinese citizens still frequently measure China in comparison to Western countries. Economic and quality of life issues are by far their main concern. But state media also holds military parity as a goal. I once saw a news program on Chinese public television boasting about China's new aircraft carrier Liaoning — before comparing it to an American carrier. "They're saying ours is still a lot smaller," a high school student pointed out to me. "And we have only one."

“Through most of Chinese history, China's main threat came from nomadic horse-riding tribes along its long northern border. Even in the Cold War, hostility with the Soviet Union made its Mongolian border a security hot spot. But the Opium Wars — and even worse, the Japanese invasion in 1937 — demonstrated how China was vulnerable to naval power along its Pacific coast. China's aggressive naval expansion in the South China Sea can be seen as the acts of a nation that has succumbed repeatedly to naval invasions — and wishes to claims dominance of its side of the Pacific in the 21st century.

“The history with opium also has led China to adopt a particularly harsh anti-narcotics policy with the death penalty applicable even to mid-level traffickers. Drug-trafficking and organized crime remain a problem, however. The explosion of celebrity culture in China has also led to punitive crackdowns on those caught partaking in "decadent lifestyles," leading to prominent campaigns of public shaming. For example, in 2014 police arrested Jaycee Chan, son of Jackie Chan, for possessing 100 grams of marijuana. His father stated he wouldn't plead for his son to avoid imprisonment.”

Image Sources: 1) Smuggling ships, Columbia University; 2) Canton factories, Columbia University; 3) Opium wars fighting, Ohio State University; 4) Attack of clipper ships, Columbia University; 5) Treaty of Nanking, Ohio State University; 6) 19th century map of China, Columbia University, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021