WINDING DOWN OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

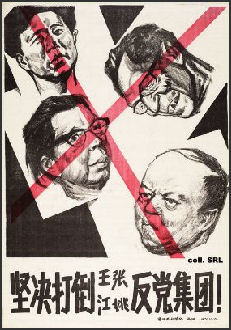

Anti-Gang-0f-Four poster In the summer of 1968, Mao called in the People's Liberation Army to restore order after chaos and upheaval had escalated to such a point the economy was on the verge of collapse. In December, 1968, in a bid to regain control and diffuse the political chaos he had unleashed, Mao ordered the Red Guards and other students to the countryside, to be “reëducated by the poor and lower-middle-class peasants.”

The main chaos had subsided by 1971. After that order was reasonably restored, According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: “Gradually, Red Guard and other radical activity subsided, and the Chinese political situation stabilized along complex factional lines. The leadership conflict came to a head in September 1971, when Party Vice Chairman and Defense Minister Lin Biao reportedly tried to stage a coup against Mao; Lin Biao allegedly later died in a plane crash in Mongolia. In the aftermath of the Lin Biao incident, many officials criticized and dismissed during 1966-69 were reinstated. Chief among these was Deng Xiaoping, who reemerged in 1973 and was confirmed in 1975 in the concurrent posts of Politburo Standing Committee member, PLA Chief of Staff, and Vice Premier. The ideological struggle between more pragmatic, veteran party officials and the radicals re-emerged with a vengeance in late 1975. Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, and three close Cultural Revolution associates (later dubbed the “Gang of Four”) launched a media campaign against Deng. In January 1976, Premier Zhou Enlai, a popular political figure, died of cancer. On April 5, Beijing citizens staged a spontaneous demonstration in Tiananmen Square in Zhou's memory, with strong political overtones of support for Deng. The authorities forcibly suppressed the demonstration. Deng was blamed for the disorder and stripped of all official positions, although he retained his party membership. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale]

Mao's propagandists tried to save Mao's skin by blaming the Cultural Revolution on the "Gang of Four." The Cultural Revolution didn't officially end until the Gang of Four was arrested in October 1976, which occurred shortly after Mao’s death. At the time of the Tangshan earthquake in 1976, the Chinese government was in the last stages of the Cultural Revolution, before Chairman Mao’s death, and was widely criticized for its insufficient mobilization immediately following the earthquake. The ban on the playing of Beethoven music lasted until March, 1977.

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four” by Alexander C. Cook (Cambridge University Press. 2017) Amazon.com; “Verdict in Peking: the Trial of the Gang of Four” by David Bonavia Amazon.com; “China Winter: Workers, Mandarins, and the Purge of the Gang of Four” by Edoarda Masi and Adrienne Foulke Amazon.com; Madame Mao “ by Ross Terrill (Stanford) Amazon.com; “Becoming Madame Mao”, a novel by Anchee Min. Amazon.com; “The Culture of Power: The Lin Biao Incident in the Cultural Revolution” by Qiu Jin Amazon.com; “Liu Shaoqi and the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Lowell Dittmer Amazon.com; About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982"by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

End of the Cultural Revolution

While efforts were made to contain the chaos and return the country to something approaching normality in the early 70s, it was not until Mao's death on September 9, 1976 that the Cultural Revolution truly ended. Earlier in July, an earthquake killed many people in Tianjin and destroyed. In October, backed by the army, Mao's successor Hua Guofeng had the Gang of Four, powerful political faction driving the Cultural Revolution, arrested, and moderates, including Deng Xiaoping, were welcomed back into the fold. [Source: Karoline Kan, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 16, 2016 James Griffiths, CNN, May 13, 2016]

The Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 1977 passed the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People's Republic of China,” which noted: “The Cultural Revolution...was responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the state and the people since the founding of the People's Republic. . . .History has shown that the Cultural revolution, initiated by a leader laboring under a misapprehension and capitalized on by counter-revolutionary cliques, led to domestic turmoil and brought catastrophe to the Party, the state and the whole people.”

China formally closed the book on the era with a 1981 party document approved by Deng declaring it a "catastrophe" for the nation, but which largely exonerated Mao. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press,May 16, 2016 =]

Later Events in the Cultural Revolution

September 13, 1971: Lin dies in a plane crash in Mongolia along with close family members and aides while apparently fleeing China. Mao is left without a successor while his wife Jiang Qing exerts ever greater influence on culture and politics as leader of the "Gang of Four." [Source: Associated Press, June 2, 2016 \^/]

1973: A major propaganda campaign was launched, mobilizing the masses with attacks against a wide range of targets, including Lin Biao, the teachings of Confucius, and cultural exchanges with the West. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

1975: A 22-year-old Xi Jinping returns to Beijing after being recommended by his fellow commune members for a place at prestigious Tsinghua University.\^/

September 9, 1976: Mao dies of complications from Parkinson's disease in Beijing at the age of 82. His death sparks a power struggle in Beijing as the Gang of Four seeks to assume control, while what's left of the party establishment conspires to wrest authority back and end the turmoil of the previous decade.\^/

October 6, 1976: Jiang Qing and the Gang of Four are arrested in a bloodless revolt led by military commanders working with Mao's successor, Hua Guofeng, effectively ending the Cultural Revolution. All four were eventually sentenced to prison and suffer primary blame for injustices and atrocities of the Cultural Revolution that might have otherwise been attributed to Mao. At her trial, Jiang declared that she was "Chairman Mao's dog. Whomever he asked me to bite, I bit."

Cultural Revolution Gets Out of Hand and Efforts to Reign in the Violence

Mao cheered on the Red Guards in hopes they would quash potential rivals and re-energize socialism. But the unleashed mobs got out of control. In many parts of China, rival groups of Red Guards clashed with one another. Sergey Radchenko wrote in China File: “It did not take long before Mao’s delight turned to disillusionment. In 1969 he called on the army to restore a semblance of order, appointing Minister of Defense Lin Biao as his heir-apparent. But Lin Biao, too, disappointed Mao. In 1971 he fled north after the uncovering of his son’s plot to assassinate Mao. Lin never made it: his plane crashed in Mongolia. Aware of unleashing a chaos that he was no longer able to control, and fearful of Soviet invasion, Mao turned to the United States.” [Source: Sergey Radchenko, China File, Foreign Policy, September 8, 2016 ||*||]

Yiching Wu told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “The disorder caused by mass insurgencies from below and paralyzing power conflicts at the top created a crisis. The nation was on the brink of anarchy. For example, some young radicals, invoking the historical example of the Paris Commune, claimed that China’s “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” would have to be toppled in order to establish a society in which the people can self-govern. Mao decided the crisis would have to be resolved. Quashing the restless rebels, the revolution cannibalized its own children and exhausted its once explosive energy. The demobilization of freewheeling mass politics in the late 1960s helped to restore the authority of the party-state, but also became the starting point for a series of crisis-coping maneuvers which eventually led to the historic changes in Chinese society and economy a decade later. [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook, Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016]

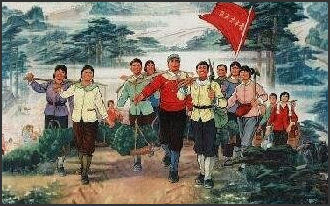

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “Rising violence later compelled party leaders to send in the People's Liberation Army to reassert control as many government functions were suspended and long-standing party leaders sent to work in farms and factories or detained in makeshift jails. To put a stop to the violence and chaos, millions of students were dispatched to the countryside to live and work with the peasantry, among them current President Xi Jinping, who lived in a cave dwelling for several years in his family's ancestral province of Sha'anxi. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 16, 2016 =]

“Much of the country was on a wartime footing during the period, with Mao growing increasingly feeble and tense relations with former ally the Soviet Union breaking out into border clashes. Radicals allied with the so-called "Gang of Four," consisting of Mao's wife Jiang Qing and her confederates, battled with those representing the party's old guard, who were desperate to end the chaos in the economy, schools and government institutions.” =

After the Activist Phase of the Cultural Revolution

The activist phase of the Cultural Revolution — considered to be the first in a series of cultural revolutions — was brought to an end in April 1969. This end was formally signaled at the CCP's Ninth National Party Congress, which convened under the dominance of the Maoist group. Mao was confirmed as the supreme leader. Lin Biao was promoted to the post of CCP vice chairman and was named as Mao's successor. Others who had risen to power by means of Cultural Revolution machinations were rewarded with positions on the Political Bureau; a significant number of military commanders were appointed to the Central Committee. The party congress also marked the rising influence of two opposing forces, Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, and Premier Zhou Enlai. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The general emphasis after 1969 was on reconstruction through rebuilding of the party, economic stabilization, and greater sensitivity to foreign affairs. Pragmatism gained momentum as a central theme of the years following the Ninth National Party Congress, but this tendency was paralleled by efforts of the radical group to reassert itself. The radical group — Kang Sheng, Xie Fuzhi, Jiang Qing, Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen — no longer had Mao's unqualified support. By 1970 Mao viewed his role more as that of the supreme elder statesman than of an activist in the policy-making process. This was probably the result as much of his declining health as of his view that a stabilizing influence should be brought to bear on a divided nation. As Mao saw it, China needed both pragmatism and revolutionary enthusiasm, each acting as a check on the other. Factional infighting would continue unabated through the mid-1970s, although an uneasy coexistence was maintained while Mao was alive.*

The rebuilding of the CCP got under way in 1969. The process was difficult, however, given the pervasiveness of factional tensions and the discord carried over from the Cultural Revolution years. Differences persisted among the military, the party, and left-dominated mass organizations over a wide range of policy issues, to say nothing of the radical-moderate rivalry. It was not until December 1970 that a party committee could be reestablished at the provincial level. In political reconstruction two developments were noteworthy. As the only institution of power for the most part left unscathed by the Cultural Revolution, the PLA was particularly important in the politics of transition and reconstruction. The PLA was, however, not a homogeneous body. In 1970-71 Zhou Enlai was able to forge a centrist-rightist alliance with a group of PLA regional military commanders who had taken exception to certain of Lin Biao's policies. This coalition paved the way for a more moderate party and government leadership in the late 1970s and 1980s. *

“The PLA was divided largely on policy issues. On one side of the infighting was the Lin Biao faction, which continued to exhort the need for "politics in command" and for an unremitting struggle against both the Soviet Union and the United States. On the other side was a majority of the regional military commanders, who had become concerned about the effect Lin Biao's political ambitions would have on military modernization and economic development. These commanders' views generally were in tune with the positions taken by Zhou Enlai and his moderate associates. Specifically, the moderate groups within the civilian bureaucracy and the armed forces spoke for more material incentives for the peasantry, efficient economic planning, and a thorough reassessment of the Cultural Revolution. They also advocated improved relations with the West in general and the United States in particular — if for no other reason than to counter the perceived expansionist aims of the Soviet Union. Generally, the radicals' objection notwithstanding, the Chinese political tide shifted steadily toward the right of center. Among the notable achievements of the early 1970s was China's decision to seek rapprochement with the United States, as dramatized by President Richard M. Nixon's visit in February 1972. In September 1972 diplomatic relations were established with Japan. *

Lin Biao's Coup Attempt and Plane Crash, a Turning Point in he Cultural Revolution

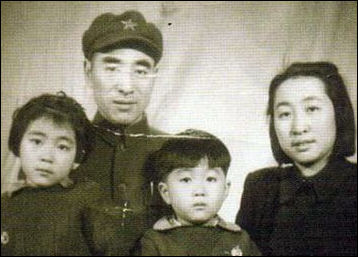

Lin Biao and Mao

Without question, the turning point in the decade of the Cultural Revolution was Lin Biao's abortive coup attempt and his subsequent death in a plane crash as he fled China in September 1971. Lin Biao was a founding father of the People’s Republic later condemned as a counter-revolutionary. Sometimes referred to as the evil genius of China or the Chinese Trotsky, he accompanied Mao on the Long March and came up with idea of the Little Red Book and chose the quotations. As the minister of defense and head of the People's Liberation Army, he served Mao well as a brilliant military tactician, a suburb propagandist and skilled organizer of the masses. For many years he stood in the wings as Mao's handpicked successor. In April 1969, the Communist Party elevated Lin Biao as Mao's heir-apparent and "closest comrade in arms."

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: “During the 1960s, the great general Lin Biao was one of Mao Tse-tung’s most trusted men. He was vice chairman of the Communist Party and Mao’s designated successor. While Lin survived the early purges of the Cultural Revolution unscathed, Mao became increasingly worried about his influence in the party. By 1971, Lin and his supporters had fallen out of favor with the Maoists, and Lin found himself isolated from the party leadership. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

There was an internal power struggle between Mao and Lin Biao, because Lin’s power in the army as well as in the Party leadership had apparently become too strong in Mao’s view. In September 1971, Lin Biao reportedly hatched a plan to assassinate Mao and take over the Chinese government. Apparently he had grown tired of waiting for Mao to die and had become disillusioned with Mao's policies. When the plot was discovered Mao was ordered to go to the Great Hall of the People because it was easiest palace to protect him and Lin Biao hopped on a plane to flee the country.

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: In 1971, “the Chinese government had uncovered a conspiracy by Lin Biao to launch a coup. The plot, code-named Project 571, also intended to assassinate Mao Tse-tung. According to the party’s account, the Lins attempted to escape China after the coup failed. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

“Despite what the Communist Party maintains, there is still a great deal of controversy over Project 571. Critics believe that it was Lin Liguo, not his father, who was probably the head of the conspiracy. In fact, Lin Biao might have been entirely innocent. The cause of the plane crash has also been disputed. Some skeptics have suggested that the plane was sabotaged or shot down. Strangely, the plane’s pilot Pan Jingyin was posthumously given the honorary title of “Revolutionary Martyr.” -

Lin Biao’s Plane Crash and Its Aftermath

Lin and his family On September 13, 1971, Lin died in a plane crash in Mongolia along with close family members and aides while apparently fleeing China. Mao was left without a successor while his wife Jiang Qing exerted ever greater influence on culture and politics as leader of the "Gang of Four."\^/

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: “On September 13, 1971, Lin, his wife, and his son Liguo boarded a plane and tried to flee to the Soviet Union. The plane’s fuel was low, and the Lins were in such a hurry that they didn’t bother to bring a copilot or navigator with them. As government officials followed the plane on radar, it passed over Mongolia and then crashed. There were no survivors, and while the nine corpses that were aboard were scorched, autopsies conducted by the Soviet Union were later able to identify the remains of the Lins. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

"We soon learned that the plane had taken off in such haste," Mao's doctor, Dr. Li Zhisui wrote, "that it had not been properly fueled. Carrying at most a ton of gasoline, the plane could not go far. Moreover it had struck a fuel truck on taking off, and the right landing gear had fallen off...The next afternoon, a message came from the Chinese ambassador in Ulaan Baatar. A Chinese aircraft with nine people on board-one woman and eight men — had crashed in the Under Khan area of Outer Mongolia. Everyone on board hade been killed. Three days later...dental records had positively identified Lin Biao as one of the dead." [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

The Lin Biao incident was a heavy blow to Mao. All of Lin’s associates in the military and the Party were subsequently arrested. After the plane crashed Mao became depressed and stayed in bed for weeks. He became so weak and breathing was so difficult he could not even cough. Lin Biao has been airbrushed out of photographs at the Mao Museum.

The immediate consequence was a steady erosion of the fundamentalist influence of the left-wing radicals. Lin Biao's closest supporters were purged systematically. Efforts to depoliticize and promote professionalism were intensified within the PLA. These were also accompanied by the rehabilitation of those persons who had been persecuted or fallen into disgrace in 1966-68. [Source: Library of Congress]

Violence Tapers Off After 1971 as Mao Becomes Involved in Party Power Struggles

After 1971, the large scale of mass killings gradually subsided, partly due to the government’s effort to restore some order from the chaos after the bloody suppression. Another contributing factor was a new wave of inter-elite struggles that burst out in the Party Central between Mao and his lieutenants during the last four years of the Cultural Revolution. As a result, Mao was in no position to focus attention on new movements against imagined “class enemies” at the grass-root level, which usually led to mass killings. [Source: Library of Congress *]

After the Lin Biao incident a second internal conflict was between Mao and Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai took place .The Lin Biao incident was a heavy blow to Mao, leaving Premier Zhou Enlai as the second leader next only to Mao. In order to balance the power in the Party Central, Mao made a series of concessions with the veteran leaders he had formerly denounced. In particular, he recalled Deng Xiaoping, Liu Shaoqi’s main assistant, back to office from exile in 1973. However, despite having promised Mao that he would never reverse the verdicts of the Cultural Revolution, Deng, sharing Zhou’s unvoiced critical view of the Cultural Revolution, took a much more aggressive approach in his effort to combat Mao’s close associates such as Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao. *

A major propaganda campaign was launched in 1973, which mobilized the masses against such widely ranging objects of attack as Lin Biao, the teachings of Confucius, and cultural exchanges with the West. To ensure the continuation of his Cultural Revolution legacy, Mao finally decided to purge Deng from the central leadership again in November 1975, one year before his own death in 1976. However, this period did not witness a peaceful ending of mass killings. First, the political campaigns before 1972, such as the campaigns of “Cleanse the Class Ranks,” “One Strike and Three Antis” and “Investigation on the May 16 Counterrevolutionary Clique,” had not been officially concluded. Second, the new purges of the internal power struggles inevitably created new political witch-hunts against other people and cadres. Third, any uprising from people to oppose the Cultural Revolution was ruthlessly suppressed by Mao and the CCP CC. Finally, armed force was used to suppress ethnic conflicts. *

Violence After Cultural Revolution Violence Tapers Off After 1971

Anti-Gang of Four poster With Mao’s approval, Deng Xiaoping, PLA’s Chief of Staff at that time, ordered military troops to attack Shadian, a Muslim hamlet in Yunnan Province. A large armed force was used, which included a division from the 14th Corps, soldiers from Mengzi military sub-district, one artillery regiment, and thousands of local militias. The whole town was razed, and more than 1,600 unarmed civilians, including 300 children, the elderly and the sick attempting to flee, were killed.

1976; April 5: The gathering of millions of people at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square during the Qingming festival season in early April 1976 was at once an outpouring of grief over the death of Premier Zhou Enlai and a mass protest against the cultural revolutionaries within the CCP leadership — namely, Mao and his inner circle. With Mao’s approval, over ten thousand soldiers, policemen and militiamen were deployed at Tiananmen Square on April 4-5 to crack down on the uprising. Since this movement was taking place simultaneously in major cities across the nation, the severe crackdown was widespread all over China. A detailed German study cited Hong Kong estimates to the effect that “millions were drawn in nationwide,” and a Taiwan intelligence source claimed that “close to 10,000 lost their lives, nationwide.”. Formally redressed two years after the Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen Incident, as part of a broader April Fifth Movement in urban China, not only pronounced the bankruptcy of the Cultural Revolution but also marked the first instance when ordinary citizens came together and challenged the regime.

1976, a Big Year in China

Trial of Gang of Four The year 1976 saw the deaths of the three most senior officials in the CCP and the state apparatus: Zhou Enlai in January, Zhu De (then chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress and de jure head of state) in July, and Mao Zedong in September. In April of the same year, masses of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in Beijing memorialized Zhou Enlai and criticized Mao's closest associates, Zhou's opponents. In June the government announced that Mao would no longer receive foreign visitors. In July an earthquake devastated the city of Tangshan in Hebei Province (See Earthquakes). These events, added to the deaths of the three Communist leaders, contributed to a popular sense that the "mandate of heaven" had been withdrawn from the ruling party. At best the nation was in a state of serious political uncertainty. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

“Deng Xiaoping, the logical successor as premier, received a temporary setback after Zhou's death, when radicals launched a major counterassault against him. In April 1976 Deng was once more removed from all his public posts, and a relative political unknown, Hua Guofeng, a Political Bureau member, vice premier, and minister of public security, was named acting premier and party first vice chairman. *

“Even though Mao Zedong's role in political life had been sporadic and shallow in his later years, it was crucial. Despite Mao's alleged lack of mental acuity, his influence in the months before his death remained such that his orders to dismiss Deng and appoint Hua Guofeng were accepted immediately by the Political Bureau. The political system had polarized in the years before Mao's death into increasingly bitter and irreconcilable factions. While Mao was alive — and playing these factions off against each other — the contending forces were held in check. His death resolved only some of the problems inherent in the succession struggle. *

Mao died on September 9, 1976 at the age of 82. By that time he suffered from Lou Gehrig's disease and emphysema, and had three heart attacks in the previous four months. A team of 16 of China's best doctors and 24 first-rate nurses were at Mao's side when he died at 12:10am. See Separate article on Mao's Death and Legacy.

Arrest of the Gang of Four

depiction of Jiang Qing

In the unprecedented April 5, 1976 demonstration in Tiananmen Square,In the dying months of the Cultural Revolution (and of Mao), protestors stood up to denounce the Gang of Four, in poems and manifestos chalked on the paving-stones or declaimed aloud. Many young Red Guards, educated by their disillusion with the Cultural Revolution, became activists in the Democracy Wall movement (1978-79) after Mao’s death. Some of them re-appeared in the Square ten years later. [Source: John Gittings, China Beat, March 31, 2010]

The radical clique most closely associated with Mao and the Cultural Revolution became vulnerable after Mao died, as Deng had been after Zhou Enlai's demise. In October, less than a month after Mao's death, Jiang Qing and her three principal associates — denounced as the Gang of Four — were arrested with the assistance of two senior Political Bureau members, Minister of National Defense Ye Jianying (1897-1986) and Wang Dongxing, commander of the CCP's elite bodyguard. Within days it was formally announced that Hua Guofeng had assumed the positions of party chairman, chairman of the party's Central Military Commission, and premier. [Source: The Library of Congress]

The Gang of Four was arrested in a bloodless coup one month after Mao's death in September 1976, marking the end of the Cultural Revolution. They were put on trial in 1980 and convicted of "persecuting to death" 34,000 people. Although the Gang of Flour clearly had a lot to answer for they were also made scapegoats. By blaming them a lot of officials were allowed to save their own skin.

On October 6, 1976 and after: After nearly a month’s careful planning with Wang Dongxin (the head of security force for the Party Central) and Ye Jianying (Vice-Chairman of the Central Military Commission), Hua Guofeng, Vice-Chairman of the CCP staged a coup d’ état to arrest Mao’s closest cohorts, designated the “Gang of Four,” which included Mao’s wife Jiang Qing and three other CCP Politburo members, namely, Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan. The Cultural Revolution ended. However, mass killings did not end peacefully in China under Mao’s shadow. Upon concluding the Cultural Revolution, the New Party Central on February 22, 1977 issued an order to kill “any counterrevolutionaries who verbally attacked Chairman Mao and Chairman Hua (Guofeng).” In less than a year, 44 famous political dissidents were executed nationwide, including Wang Shengyou in Shanghai and Li Jiulian in Jiangxi Province, all of whom were formally rehabilitated later after their death.

See Gang of Four in the first Cultural Revolution section.

Trial of the Gang of Four

One of the more spectacular political events of modern Chinese history was the month-long trial of the Gang of Four and six of Lin Biao's closest associates. A 35-judge special court was convened in November 1980 and issued a 20,000-word indictment against the defendants. The indictment came more than four years after the arrest of Jiang Qing and her associates and more than nine years after the arrests of the Lin Biao group. Beyond the trial of ten political pariahs, it appeared that the intimate involvement of Mao Zedong, current party chairman Hua Guofeng, and the CCP itself were on trial. The prosecution wisely separated political errors from actual crimes. Among the latter were the usurpation of state power and party leadership; the persecution of some 750,000 people, 34,375 of whom died during the period 1966-76; and, in the case of the Lin Biao defendants, the plotting of the assassination of Mao. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Man He of Williams College wrote: Conducted over the winter of 1980-81, the Gang of Four trial was the defining event of China’s post-Mao transition in legal, political, and cultural senses. Not only did it signal a return to law and order after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, it affirmed the continuing rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its authority to render a verdict on China’s recent past.

The indictment highlights the process by which the trial evolved from being a “settling of accounts” to becoming a case of transitional justice. Between 1976 and 1980, while the CCP was engaged in behind-the-scenes deliberations and Deng Xiaoping secured power, the meaning of “gang” evolved from describing “factional cliques” into the “gang” of the Gang of Four—a “counterrevolutionary criminal syndicate” responsible for persecuting 729,511 people and killing 34,800. Departing from the violent accusations that characterized the Cultural Revolution [i.e., “criticism and struggle” and “speaking bitterness”], the finalized indictment, which went through thirty revisions, turned to law to complete a narrative that undid the recent past through “new ways of thinking law, speaking law, and performing law”.When the indictment was delivered on the opening day of the trial, November 20, 1980, its authority rested on a legal order rather than moral values. [Source: Man He, Williams College, MCLC Resource Center Publication, July, 2017]

“The public reading of the charges in the special courtroom, located at No. 1 Justice Road, where audience’s visceral antagonism toward Jiang Qing was palpable. “Seeing her performance really made you want to vomit,” one reporter wrote. In his book: “The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four, Alexander C. Cook “focuses upon the chief defendants’ testimonies, or methods of legal storytelling. Cook discerns four defense strategies: the confessional mode (adopted by Wang Hongwen, Chen Boda, and the generals linked to the Lin Biao case), contestation (Yao Wenyuan), silence (Zhang Chunqiao), and transcendence (Jiang Qing).

“While the confession and contestation modes entailed differing approaches, both appealed for “avoiding or mitigating punishment” by “weaving their own stories into the fabric of the larger trial narrative”. More threatening to the trial’s order was Zhang Chunqiao’s disinterested silence, which Cook reads as exposing the violence inherent in the courtroom ritual as well as potentially opening a new space that criticized the testimonies’ constraining force from within the legal proceedings. Such a silent protest, however, did not change the “tedious and un-dramatic” tone of the inquiry, and the official press treated Zhang’s silence as an admission of guilt. The authority of the court was not sufficiently challenged until Jiang Qing appealed “from within the legal narrative to an authority without”. Speaking directly to a “personified History,” Jiang Qing asked, “If I am guilty, how about you all?” B appealing to a higher kind of justice, Jiang Qing called into question the court’s authority to retrospectively put revolution on “trial”. In this manner, the “white-boned demon” not only became the embodiment of the Cultural Revolution, she was the Monkey King in her transcendence of law’s constraining force. That members of the public admitted “a begrudging respect for her defiant stand and acknowledge the validity of her claim”, suggests an inherent shortcoming to the persuasiveness of legal storytelling.

In January 1981 the court rendered guilty verdicts against the ten. Jiang Qing, despite her spirited self-vindication and defense of her late husband, received a death sentence with a two-year suspension; later, Jiang Qing's death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. So enduring was Mao's legacy that Jiang Qing appeared to be protected by it from execution. The same sentence was given to Zhang Chunqiao, while Wang Hongwen was given life and Yao Wenyuan twenty years. Chen Boda and the other Lin Biao faction members were given sentences of between sixteen and eighteen years.

In China the Gang of Four became known as the ‘shanghai clique.” Jiang never repented. She committed suicide in prison. Yao Wenyuan was released from jail at the age of 71 in 1996 after serving a 20 year prison sentence. The last surviving member of the Gang of Four, he died in December 2005. Zhang Chunqiao, another member, died of cancer of April 2005. Wang died in 1992.

Book: “The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four” by Alexander C. Cook (Cambridge University Press. 2017)

Meaning of the Gang of Four Trial

In his review off “The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four”, Man He of Williams College wrote: “Cook interprets the trial through the lens of “transitional justice,” a legal term that appeared in the 1990s to describe the move away from authoritarian regimes in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere. Although the term was not used by Chinese at the time, state media did present the trial as a way to address China’s recent political turmoil and pave the way for a better future. However, unlike other examples of transitional justice, the Gang of Four trial produced inconclusive results. Cook sees the trial as continuing the debate between scientism and humanism that had dominated China since the late nineteenth century. Whereas the scientist perspective blamed the Cultural Revolution on corrupt individuals in positions of power, the humanist critique traced the Cultural Revolution to a lack of human values in politics. [Source: Man He, Williams College, MCLC Resource Center Publication, July, 2017]

The verdict—which, like the indictment, also went through thirty drafts—came in tandem with the June 1981 “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of the Party since the Founding of the State.” Whereas the former announced the crimes of the Gang of Four as violations of statutory law , the latter blamed the “decade of chaos” on the party’s lack of experience and violation of the objective laws of history. Notably, both the verdict and resolution aimed to bring into being new social realities. The trial redefined the violence of the Cultural Revolution from an issue of party discipline to a matter of law, at the same time that the resolution elevated, or returned, the matter of law to the laws of history.

“Early in the Conclusion, Cook observes that the trial reanimated a century-old debate in China: “Should modernization be motivated by instrumental rationality and material development or by humanistic values and spiritual renewal?”. His answer is that, while the trial attempted to establish instrumental rationality as the solution to China’s political problems, the humanist position continued to resonate in academic journals and sectors of the official media; the debate ended with the 1983 campaign against spiritual pollution, in which “the moral imperative of socialism was reduced to obedience to authority in the name of law and order”. Chinese socialism may have survived the Cultural Revolution, but “what remained was an official ideology bereft of positive values that people could believe in”.

Impact of the Trial of the Gang of Four and the Rejection of Maoism

The net effect of the trial was a further erosion of Mao's prestige and the system he created. In pre-trial meetings, the party Central Committee posthumously expelled CCP vice chairman Kang Sheng and Political Bureau member Xie Fuzhi from the party because of their participation in the "counterrevolutionary plots" of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing. The memorial speeches delivered at their funerals were also rescinded. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

There was enough adverse pre-trial testimony that Hua Guofeng reportedly offered to resign the chairmanship before the trial started. In June 1981 the Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh National Party Congress Central Committee marked a major milestone in the passing of the Maoist era. The Central Committee accepted Hua's resignation from the chairmanship and granted him the face- saving position of vice chairman. In his place, CCP secretary general Hu Yaobang became chairman. Hua also gave up his position as chairman of the party's Central Military Commission in favor of Deng Xiaoping. The plenum adopted the 35,000-word "Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People's Republic of China." The resolution reviewed the sixty years since the founding of the CCP, emphasizing party activities since 1949. A major part of the document condemned the ten-year Cultural Revolution and assessed Mao Zedong's role in it. "Chief responsibility for the grave Left' error of thecultural revolution,' an error comprehensive in magnitude and protracted in duration, does indeed lie with Comrade Mao Zedong . . . . [and] far from making a correct analysis of many problems, he confused right and wrong and the people with the enemy. . . . Herein lies his tragedy." At the same time, Mao was praised for seeking to correct personal and party shortcomings throughout his life, for leading the effort that brought the demise of Lin Biao, and for having criticized Jiang Qing and her cohort. Hua too was recognized for his contributions in defeating the Gang of Four but was branded a "whateverist." Hua also was criticized for his anti-Deng Xiaoping posture in the period 1976-77. *

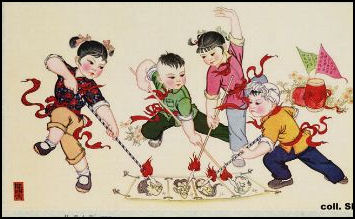

Celebration after sentencing at the Gang of Four trial

Several days after the closing of the plenum, on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the CCP, new party chairman Hu Yaobang declared that "although Comrade Mao Zedong made grave mistakes in his later years, it is clear that if we consider his life work, his contributions to the Chinese revolution far outweigh his errors. . . . His immense contributions are immortal." These remarks may have been offered in an effort to repair the extensive damage done to the Maoist legacy and by extension to the party itself. Hu went on, however, to praise the contributions of Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De, Peng Dehuai, and a score of other erstwhile enemies of the late chairman. Thus the new party hierarchy sought to assess, and thus close the books on, the Maoist era and move on to the era of the Four Modernizations. The culmination of Deng's drive to consolidate his power and ensure the continuity of his reformist policies among his successors was the calling of the Twelfth National Party Congress in September 1982 and the Fifth Session of the Fifth National People's Congress in December 1982. *

Image Sources: Photos: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; Gang of Four photo, Ohio State University; Lui picture Wikicommons, Wen and Hu pictures China.org ; restaurant and costumes; Asia Obscura http://asiaobscura.com/ ;

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021