RED GUARDS

The Red Guard who were involved in much of the early action of the Cultural Revolution was made up mainly of high-school- and university-age youths. They wore red armbands that read: “Red-Color New Soldier.” In her book "Wild Swans", former Red Guard Jung Chang wrote, Mao wanted to establish "absolute loyalty and obedience to himself alone," and to do this he needed terror. "He saw boys and girls in their early teens and early twenties as his ideal agents" because they were easy to manipulate.

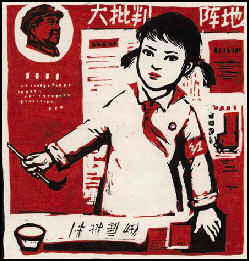

Austin Ramzy wrote in the New York Times: The Red Guards were students who answered Mao’s call for continuing revolution, Red Guards formed large groups that targeted political enemies for abuse and public humiliation. Sometimes the groups even battled one another. Under a campaign to wipe out the “Four Olds” — ideas, customs, culture, habits — they carried out widespread destruction of historical sites and cultural relics. As the Red Guards grew more extreme, the People’s Liberation Army was sent in to control them. [Source: Austin Ramzy, New York Times, May 14, 2016]

Tens of thousands of young people were enlisted in Mao's Red Guards. They carried out Mao’s orders his orders and lived by the words of the Little Red Book of Mao's quotations. They went on great pilgrimages to places associated with the Chinese Communist Party revolution [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The Jinggang Mountains in Jiangxi Province is one of the most important sites of the Communist Revolution and a center of Red Tourism. The place is celebrated with posters, songs and operas. During the Cultural Revolution it was pilgrimage site for young Red Guards, who took advantage of a nationwide "networking movement" to get there and often made the journey on foot to relive the days of the Long March. At one point more than 30,000 Red Guards arrived a day, producing food and housing shortages and sanitation problems. These conditions lasted for around three months when the government began to take moves to discourage so many young people from coming.

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: RED GUARD VIOLENCE AND DESTRUCTION factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com; REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION ENEMIES AND THE VICIOUS ATTACKS ON THEM factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; BACK TO THE COUNTRYSIDE MOVEMENT OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com

Beginning of the Red Guard Movement

The May 1966 poster by the philosophy professor Nie Yuanzi is credited with launching the Red Guard Movement. Many students, whose "suspect" revolutionary background denied them opportunities, embraced the Red Guard movement as a way of showing "they could be as revolutionary as their parents" and as a means of exacting revenge against party members who had discriminated against them.

In August 1966, Mao stood in Tiananmen Square before one million Red Guards, many of them waving Little Red Books and chanting slogans like "Down with the Four Olds!, Up with the Four News!, New Thinking! New Customs! New Habits." In February 1967, Red Guards led 3 million peasants into Shanghai for a pro-Mao rally. Mao met with hundreds of thousands of young people in Tiananmen Square in Beijing 8 times during the Cultural Revolution.

Later the Red Guard movement spread to provinces and villages across China where local committees, encouraged by Red Guards imprisoned, tortured and murdered a surprisingly large number of "class enemies," tried by "peasant juries" in kangaroo courts. The Red Guard movement ousted municipal party members in Shanghai in January 1967 and eventually shut down the entire Chinese educational system. Many of the "class enemies" were simply victims of violent score-settling in the absence of an impartial police force or an independent legal system.

Mao and the Red Guard

Mao felt that he could no longer depend on the formal party organization, convinced that it had been permeated with the "capitalist" and bourgeois obstructionists. He turned to Lin Biao and the PLA to counteract the influence of those who were allegedly 'left' in form but 'right' in essence." The PLA was widely extolled as a "great school" for the training of a new generation of revolutionary fighters and leaders. Maoists also turned to middle-school students for political demonstrations on their behalf. These students, joined also by some university students, came to be known as the Red Guards. Millions of Red Guards were encouraged by the Cultural Revolution group to become a "shock force" and to "bombard" with criticism both the regular party headquarters in Beijing and those at the regional and provincial levels. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

In June 1966 middle schools and universities throughout the country closed down as students devoted all their time to Red Guard activities. Millions of these young students were encouraged to attack "counterrevolutionaries" and criticize those in the party who appeared to have deviated from Maoist thought. In his book “On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet,” Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “The first activists were young students called Red Guards, who began attacking their teachers and administrators, searching to uncover those who were following the capitalist road and had sneaked into the party... In Beijing, the incipient chaos in schools in June and July prompted Liu Shaoqi to send work teams“exercise leadership,” that is, to try to restrain the students and restore order. Mao, however, disapproved of work teams constraining workers and students, that is, controlling the Cultural Revolution, labeling this as an act of “white terror”. Consequently, at the start of August he intervened to clarify the direction of the new campaign by publishing his famous “big-character poster”, which said tersely and forcefully, “Bombard the Headquarters”, that is, vigorously attack the party headquarters to uncover and criticize those in power who were taking China down the wrong road to capitalism. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, “ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009. Goldstein is a professor in the Department of Anthropology at Case Western Reserve University]

“Red Guard activities were promoted as a reflection of Mao's policy of rekindling revolutionary enthusiasm and destroying "outdated," "counterrevolutionary" symbols and values. Mao's ideas, popularized in the Quotations from Chairman Mao, became the standard by which all revolutionary efforts were to be judged. The "four big rights" — speaking out freely, airing views fully, holding great debates, and writing big-character posters — became an important factor in encouraging Mao's youthful followers to criticize his intraparty rivals. The "four big rights" became such a major feature during the period that they were later institutionalized in the state constitution of 1975. The result of the unfettered criticism of established organs of control by China's exuberant youth was massive civil disorder, punctuated also by clashes among rival Red Guard gangs and between the gangs and local security authorities. The party organization was shattered from top to bottom. (The Central Committee's Secretariat ceased functioning in late 1966.) *

The resources of the public security organs were severely strained. Faced with imminent anarchy, the PLA — the only organization whose ranks for the most part had not been radicalized by Red Guard-style activities — emerged as the principal guarantor of law and order and the de facto political authority. And although the PLA was under Mao's rallying call to "support the left," PLA regional military commanders ordered their forces to restrain the leftist radicals, thus restoring order throughout much of China. The PLA also was responsible for the appearance in early 1967 of the revolutionary committees, a new form of local control that replaced local party committees and administrative bodies. The revolutionary committees were staffed with Cultural Revolution activists, trusted cadres, and military commanders, the latter frequently holding the greatest power. *

The resources of the public security organs were severely strained. Faced with imminent anarchy, the PLA — the only organization whose ranks for the most part had not been radicalized by Red Guard-style activities — emerged as the principal guarantor of law and order and the de facto political authority. And although the PLA was under Mao's rallying call to "support the left," PLA regional military commanders ordered their forces to restrain the leftist radicals, thus restoring order throughout much of China. The PLA also was responsible for the appearance in early 1967 of the revolutionary committees, a new form of local control that replaced local party committees and administrative bodies. The revolutionary committees were staffed with Cultural Revolution activists, trusted cadres, and military commanders, the latter frequently holding the greatest power. *

“The radical tide receded somewhat beginning in late 1967, but it was not until after mid-1968 that Mao came to realize the uselessness of further revolutionary violence. Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, and their fellow "revisionists" and "capitalist roaders" had been purged from public life by early 1967, and the Maoist group had since been in full command of the political scene. *

Members of the Red Guard

The Red Guard was made up mainly of high-school- and university-age youths. They wore red armbands that read: “Red-Color New Soldier.” In her book "Wild Swans", former Red Guard Jung Chang wrote, Mao wanted to establish "absolute loyalty and obedience to himself alone," and to do this he needed terror. "He saw boys and girls in their early teens and early twenties as his ideal agents" because they were easy to manipulate.

One woman, now an editor of a magazine in Hong Kong, told the Washington Post, she joined the Red Guard when she was 18 "because I felt it was a glorious thing to do...In the beginning I had no independent thoughts. I thought what the Communist Party asked me to think. I did what the Communist Party asked me to do. But I saw close friends who could kill or be killed in a very inhuman way. I began to have doubts about our system and our government. I learned that very kind and even gentle people can change personality in such a situation. Some of the gentlest people became very cruel."

People joined the Red Guards because there wasn’t much else to do and participated in the rallies because if they didn’t they could be accused of being class enemies. The photographer Li Zhensheng told U.S. News and World Report, “If the crowd chanted, I chanted; if everyone raised their fists, I raised my first...If you didn’t follow the crowd they could easily turn on you.”

Becoming a Red Guard

young Red Guard

Lishui is the nickname of a farmer in the Tianjin area who became a Red Guard. Karoline Kan wrote in Foreign Policy Magazine: “Lishui’s story began in May 1966, when he was 18 years old. He told me he heard a government announcement on the village loudspeaker: “Some representatives of the Bourgeoisie have creeped into our party, our government, our military, and our cultural departments. They are a group of counterrevolutionary revisionists and they are waiting for the right moment to seize power.” [Source: Karoline Kan, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 16, 2016 \=]

“One night not long after the announcement, when Lishui’s father was putting on a shadow play under candlelight for his younger children, Lishui’s heard the sound of drum, gongs, and voices, chanting, “Down with the landlords and their bastards!” “What’s that?” Wang’s young brothers and sisters asked. “Red Guards,” said their father. \=\

“Not long after, Lishui told me, he found that almost every young person around him had become a Red Guard. He soon joined them, for reasons he could not articulate clearly. “It’s like being pushed by a flood,” he said. There was also an intitial attraction to the position. There was less work to do at Lishui’s village production team, because so much time was spent on political activities. His younger siblings did not need to attend school.” \=\

Kind of People That Became Red Guards

Dai Jianzhong, a sociologist in Beijing, attended Tsinghua University High School, where the first Red Guard groups were formed. He told the New York Times: “My impression was that, in a sense, the Cultural Revolution had already begun in 1964. Even before the Cultural Revolution, there were divisions in our class over family background. Many students from bad class backgrounds like me couldn’t win acceptance to the special university preparatory classes, or membership in the Youth League. Those chances went disproportionately to the children of officials. The fact is that they were much more mature and in-the-know than us. They really did see themselves as the heirs to power – that our parents won the country and so we’re the natural heirs – and this thinking has continued into the present. [Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“After the Cultural Revolution broke out, they were also the ones who formed the first Red Guard group. Kids from bad family backgrounds didn’t have a chance of joining. They first formed by holding secret meetings in the grounds of the Old Summer Palace. From early June, the incidents of beating and berating teachers and the principal began. The principal would stand on the platform. “Stand up!” they’d yell. He’d stand up. “Head down!” He’d lower head. They’d press his head down further. Then it took off from there.” ~~

Motives for Joining the Red Guards

Cao Dengju, then a high school student at Chongqing told Associated Press that he joined the Red Guards partly out of anger. “But he also felt a freedom he hadn’t tasted before, thanks to what he called a “power vacuum”. “Freedom was scarce before the Cultural Revolution. That’s why we unleashed so much energy,” Cao, now 69 and a retired materials science professor at Chongqing University, said in a recent interview. “Anarchy was what we all longed for. It felt too repressed before the Cultural Revolution.” Cao soon joined a Red Guard faction. Like others, he published political commentaries and took part in armed conflict. “In Mao’s words, we felt we were liberated,” Cao said. “In fact, we fell into a bigger trap and became his pawns.” [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

“Zheng, first tasked with picking up dead bodies for the 815 faction, was familiar with Communist slogans like “fear neither hardship nor death”. “I saw too many deaths. They were so poor,” he said. “I spent time with families of some of the victims. My tears barely dried. “They were good people, and they died defending chairman Mao’s revolutionary line. What’s so precious about my life then? It was a mixture of sympathy for our people and hatred towards the other side. “I was willing to give my life to take theirs with a grenade, if I could catch fighters from the other side.”

“His anger, stirred up by sympathy for the dead, escalated after July 1967 when Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, a member of the party’s leadership, trumpeted violence with the slogan “attack with words and defend with force”. A month later, Zheng presided over the killing of the two captives, something he still regrets. “Why do terrorists blow themselves up nowadays? They were manipulated by extremist propaganda and hatred upon seeing others killed in the battlefield,” Zheng said, drawing an analogy with his mindset during the Cultural Revolution.

“The slogan “attack with words and defend with force” was invented by a rebel group in Henan province headed by Yuan Yuhua, then a worker at a pork factory. Unlike Zheng, Yuan remains a firm supporter of the Cultural Revolution and the armed conflict it spawned, and says he never felt fooled or manipulated. Yuan said the people and Mao relied on each other to crush the bureaucrats in the middle. “Some might say we were used. But we preferred to be used. Without it, we are slaves. Before the Cultural Revolution, we had no democratic rights,” he said. “Before the Cultural Revolution, if you opposed a low-level leader, you would be labeled an enemy of the party ... during the revolution, we could criticize anyone except Mao and other top leaders.“

Confessions of a Red Guard

Yu Xiangzhen was a Red Guard during China's Cultural Revolution, He told CNN: “I have lived a life haunted by guilt. In 1966, I was one of Chairman Mao Zedong's Red Guards. Myself and millions of other middle and high school students started denouncing our teachers, friends, families and raiding homes and destroying other people's possessions. Textbooks explain the Cultural Revolution — in which hundreds of thousands of people were killed and millions more abused and traumatized — as a political movement started and led by Mao "by mistake," but in reality it was a massive catastrophe for which we all bear responsibility. [Source: Yu Xiangzhen, CNN, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“On May 16, 1966, I was practicing calligraphy with my 37 classmates when a high-pitched voice came from the school's loudspeaker, announcing the central government's decision to start what it called a "Cultural Revolution." It was my first year of junior high, I was just 13. "Fellow students, we must closely follow Chairman Mao," the speaker bellowed. "Get out of the classroom! Devote yourselves to the Cultural Revolution!" Two boys rushed out of door, heading to the playground yelling something. I left more slowly, holding hands with my best friend Haiyun as we followed everyone else outside. It would be my last normal day of school. ~~

“As Red Guards, we subjected anyone perceived as "bourgeois" or "revisionist" to brutal mental and physical attacks. I regret most what we did to our homeroom teacher Zhang Jilan. I was one of the most active students — if not the most revolutionary — when the class held a struggle session against Ms. Zhang. I pulled accusations out of nowhere, saying she was a heartless and cold woman, which was entirely false. Others accused her of being a Christian because the character "Ji" in her name could refer to Christianity. Our groundless criticisms were then written into "big character" posters — a popular way of criticizing "class enemies" and spreading propaganda — 60 of them in total, which covered the exterior walls of our classroom building. ~~

“My generation grew up drinking wolf's milk: we were born with hatred, and taught to struggle and hate everyone. Some of my fellow Red Guards argue that we were just innocent children led astray. But we were wrong. It pains me that many of my generation choose to forget the past and some even reminisce about the "good old days" when they could travel the country as privileged, carefree Red Guards. I do not confess because I committed fewer sins or experienced fewer hardships than others. I bear responsibility for many tragedies and abuses, and I can only express my regret to those who lost their loved ones during the Cultural Revolution. But I do not ask for forgiveness. I want to tell the truths of the Cultural Revolution as someone who lived through the madness and chaos, to warn people of the spectacular destructiveness, so that we can avoid ever repeating it. Fifty years on, however, I am worried by the increasing leader-worship we see in state media, similar to the ideological fervor that surrounded Mao. We must stay vigilant. We can't have the gruesome brutality of the Cultural Revolution start again.” ~~

Yu Xiangzhen, a Former Red Guard, Recalls Her Experience

Young Red Guard

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Yu Xiangzhen was an idealistic 14-year-old when the Cultural Revolution broke out, and among the first to form a Red Guards group. "We were taught that Chairman Mao was closer to us than our parents — he was like a god to me," she says. From the first, she had doubts: when she saw fellow students berating and humiliating teachers, hacking off their hair and pouring glue over them; when she watched her peers assaulting "capitalists" and "rightists". It felt wrong, and yet, "I still thought it was right because everything I was hearing was that we needed to break the old world to build a new one...I didn't think these people deserved to be beaten up....[But in refusing to take part] I felt I was, indeed, not brave enough. It was a loss of face." [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

Then, she says, came "something so horrifying I will never be able to forget it as long as I live". There is no doubt she is still traumatised, and her voice rises to a shriek as she describes it. "It was dark — I was standing by the side of a road, waiting for my friends. I heard someone whispering for water and saw a man crawling towards me from the basketball court," she says. "He was covered in blood. The blood on his head had congealed already. I was terrified. Then I saw the court — it was almost covered by dead bodies." All, she believes, beaten to death by Red Guards.

Yet, for these teenagers, it was a heady as well as a frightening time. Hours after witnessing the atrocity, Yu was on a train to Shanghai. They were travelling first to spread the cause — bearing leaflets titled "Long live the red terror" — but then "it just became travel and leisure". Trains were free to Red Guards; food and lodgings awaited them. "There were no plans, no destinations” I was just very happy."

"The Red Guards who were most active had [political] problems in their family and tried to prove they were different," she suggests. "Every time we get together, I look for the people who were most brutal. One told me it was exciting to go to people's houses and smash things and beat them up. You felt you could do whatever you wanted — that you were in control” And you thought it was the right thing to do."

“Destroy the Four Olds”

ransacking a Russian church in Harbin

Driven by Mao’s edict to attack the “four olds,” gangs of Red Guards smashed up temples, destroyed artwork, and demolished libraries and cemeteries. The Communist Party cheered on the destruction, with the People’s Daily publishing a June 1 editorial exhorting cadres to “sweep away all monsters and demons!” A Red Guard leader who led raids on temples and other cultural treasures told the Christian Science Monitor: “Chairman Mao called for us to ‘Destroy the Four Olds’… and whatever Chairman Mao said, we did it right away.” [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

Zehao Zhou wrote in USA Today: “Waves of violence swept across the country: Foreign embassies were sacked. Political untouchables were summarily deported from the city or even buried alive. Suicides became widespread. Among the most atrocious events that occurred during the tumultuous summer of 1966 was the “Destroy the Four Olds Campaign.” Anything that expressed old ideas, old habits, old customs and old culture was subject to the wrath of the Red Guards. [Source: Zehao Zhou, USA Today Network, May 14, 2016 ^*^]

“In just a few weeks, the material representation of 5,000 years of Chinese civilization was summarily destroyed or irrevocably damaged — the equivalent of the eradication of all material symbols of the Greek, Roman and Judeo-Christian traditions. The numbers are mind-boggling: Almost 90 percent of Tibet’s monasteries and temples were razed and roughly 74 percent of the historic sites in the birthplace of Confucius, China’s Jerusalem, were obliterated. ^*^

“In my own Shanghai neighborhood, what I will always remember is when a pack of Red Guards attacked our community church, brought out all of its Bibles into the middle of the street and set them on fire. That horrific moment — seeing the sky darkened with the floating ashes of burned Bibles — remains seared in my memory even now.” ^*^

See Separate Article VIOLENCE AND DESTRUCTION ASSOCIATED WITH THE RED GUARDS factsanddetails.com

Red Guard Factionalism

The Red Guards were by no means unified. Their movement quickly splinted into different factions with different views, different levels of revolutionary enthusiasm, and different interpretations of Maoist ideology and the goals of the Cultural Revolution.Guobin Yang, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times: The Cultural Revolution “endorsed the use of so-called big character posters for mass criticism. And a Red Guard press flourished. Several thousand titles of Red Guard papers appeared around the country. These publications gave them channels for expression they couldn’t have dreamed of before [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 15, 2016].

“Dissent was also a direct result of factional conflicts. Red Guard factionalism didn’t start with physical violence, but with debates — verbally or in their “small papers.” For example, Yu Luoke’s famous essay “On Family Origin” was written in 1966 in response to the notorious couplet that stated that if you came from a revolutionary family, then you must be a revolutionary, and if you came from a bourgeois family, then you were a counterrevolutionary.

“Yu’s ideas were revolutionary and utterly subversive in that context. In essence, he was calling on people to rise up and fight for equality. These ideas struck a chord among people who had suffered discrimination or persecution because of their family background. Later, in the Democracy Wall movement in the late 1970s, these ideas began to be expressed in the language of human rights. I should add, though, that the ideas Yu challenged and the people who embodied those ideas are well and alive in China today.

“Chinese of Yu Luoke’s age who were in Beijing then have said that reading his essays was an electrifying experience. What was it that he and other young dissenters were challenging They were challenging unequal political treatment on the basis of family background. They were also challenging the privileged new class of party elites and cadres.

“At the start of the Cultural Revolution, the first Red Guards were generally the children of high-ranking officials in Beijing’s elite middle schools. But Yu was a factory apprentice and he argued in his essay “On Family Origin” that China had a feudal caste system. If you happened to come from a family considered to be anything other than “red,” then you were doomed to second-class citizenship for life. Yu also attacked the “born red” mind-set among children of the party elites. In August 1966, some students of the elite middle school attached to Peking University issued a statement with the title “The Born Reds Have Stood Up!” It claimed if their fathers had taken over the ruling power of the country, then they would be the natural heirs to this power. Yu argued that this was a reactionary position that violated Mao’s teachings and Marxist theory. Others, especially Yang Xiguang in Hunan, challenged the political status quo. They believed that China’s Communist power elites had formed a new “red capitalist class” and called for its overthrow by means of revolutionary violence.”

At this stage “they were emulating Mao. They wanted to become young revolutionary theorists like Mao. Yang Xiguang’s most influential essays copied Mao’s rhetorical style and language.

Disillusionment came later, with the beginning of the sent-down movement and then the Lin Biao incident in 1971. Lin Biao was minister of defense and Mao’s designated successor. When Lin suddenly died in a plane crash on Sept. 13, 1971, and was declared a counterrevolutionary, it struck doubt into millions of young people....Red Guard factionalism resulted in nothing but violence. Many people felt betrayed, like puppets being used by the power elites. After they were sent down to villages from late 1967, disillusionment deepened. They also saw a China unknown to them before, very poor and harsh.

Yellow Cover Books and the Spread of Information in the Cultural Revolution

Red Guards in Beijing

Guobin Yang, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times: “I’m fascinated by the role previously restricted books played in sowing the seeds of new thinking among the Red Guard generation. These were the translated ‘‘yellow cover’’ and ‘‘gray cover’’ books, originally meant to be read only by select officials so they could understand the thinking of ideological foes. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 15, 2016]

“The “yellow cover” books were mainly works of post-Stalinist Russian literature such as Ilya Ehrenburg’s “The Thaw.” There were also some works of the American Beat Generation” and the British “angry young men” variety, such as Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” and Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye.” The “gray cover” books were works of social science, philosophy and political analysis such as “The Revolution Betrayed” by Leon Trotsky and “The New Class’’ by the Yugoslav dissident intellectual Milovan Djilas. These were translated and printed in the first few years of the 1960s as “internal publications.” They allowed officials to study ideas considered too dangerous for the public. Only top-ranking party cadres and intellectuals had access to them. The purpose was to prepare party cadres for the polemical war with the Soviet Union, which intensified in 1963 and ’64.

“Chinese youth began to read them in the middle of the Cultural Revolution, when control broke down and books from officials’ homes and offices began to circulate. Their ideas were subversive to a generation that had learned nothing about the dark side of Stalinism or the irreverent style in Western modernist literature. The internet of the ’60s and ’70s was the social networks among sent-down youth. The sent-down movement had scattered them around the country, but they were connected because they had been classmates, schoolmates or friends. They wrote letters to friends in different places.

“A great opportunity for exchanging information was when they visited homes during holidays, especially during the Lunar New Year. They would bring information back home to share with one another. Then when they went to the villages, they would bring new information, and books and food, back to their villages or farms. They borrowed books from one another, copied books onto their notebooks and sometimes stole books from libraries that had been sealed during the Cultural Revolution.

Opposing the Cultural Revolution at One’s Peril

Humiliation in Tibet

According to Associated Press: Despite the freedom to accuse, slander and even kill, even the most oblique criticism of Mao could be dangerous, if not fatal. Li Zhengtian, a graduate from Guangzhou’s Academy of Fine Arts, had a narrow escape. In a hand-written poster and a series of debates on the streets of Guangzhou, Li attacked the golden rule of the revolution: “Down with whoever opposes Mao.” While respecting the authority of Mao, Li Zhengtian criticized some top leaders for using Mao’s personality cult to violate human rights. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

“No thinking, research, exploration, or questioning allowed [against Mao] ... simply nullifies 800 million brains,” an article posted by Li Zhengtian and two others in November 1974 said, referring to the Chinese population at the time. “It should be stated that other than those who committed murder, arson, sexual harassment, theft, or provoked armed conflicts, all people should have their democratic rights protected.”

“The article went off like a bomb and unnerved the propaganda machine, which slammed it for openly respecting everyone, including the “bourgeoisie”. Guangzhou residents swarmed to see the poster, some staying after dusk to keep on reading the 26,000-character article by torchlight. Hand-written copies were relayed as far away as Beijing, more than 1,800km away. His bold defence of human rights soon got Li Zhengtian in trouble, but he survived to talk about it. Yu Luoke, a worker who criticized the classification of people according to their family backgrounds and Zhang Zhixin, who questioned Mao for starting the Cultural Revolution, were both executed.

“After more than a hundred struggle sessions, during some of which he was beaten to unconsciousness, Li Zhengtian was sent to hard labor in a mine for being the head of an “anti-party clique”. Looking back at the decade-long Cultural Revolution, Li Zhengtian said that what stood out most in retrospect was the lack of rule of law. “It was a lawless place,” he said of his time in custody. “The investigators could decide who was guilty and who to shoot on their own.”

Red Guard Generation

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “In his book, The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China”, Guobin Yang, professor of communication and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, writes how the Party’s control of information and images createda world of enchantment, mesmerization, and danger, one that combined a sense of infinite possibilities and hopes with a sense of danger and threat. It was this world that gave reality, urgency, and potency to the political culture of that historical era. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

“Yang is aware that generations are difficult to define and he is careful with his words. Roughly speaking, these people were born around the time of the Communist takeover in 1949, and for them, joining the student units known as Red Guards was central to their lives. In China, few use the term “Red Guard generation” because the guards are seen negatively—they were the young people whipped up by Mao and the Party to attack, often viciously, educated people and the government, as well as books, temples, churches, and anything that seemed old. Most people of that generation prefer to be called zhiqing, or educated youth, a much broader term for any young person sent down to the countryside after Mao decided that the Red Guards had gotten out of control. This emphasizes their transformation into victims; but Yang’s choice is a good one because it focuses attention on the astounding outburst of violent politics fifty years ago, from 1966 to 1967, when the Red Guards were at their peak.

During the period of armed violence in Chongqing in 1967, Red Guards fought bloody battles with knives, pistols, machine guns, and even floating artillery platforms from which they bombarded their enemies while sailing on the Yangtze River.” Yang makes clear, these battles were reenactments of the films and stories they had been shown and told about the revolution of the 1930s and 1940s. The Red Guards sent themselves off to battle with slogans drawn from war movies, and wrote moving eulogies for the hundreds killed that echoed the rhetoric of the Communist wartime myths.”

Posters

“But Yang is interested in showing more than how young people were conditioned to accept violence and obedience. He also wants to explain how they broke free of this straitjacket. One way was to use the sudden, if limited, freedom that Mao had given them to think and argue. It is well known that Red Guards pasted posters around towns denouncing their imagined enemies, but many also wrote thoughtful criticisms of the system. One was Yu Luoke, who attacked the idea that children of the revolutionary elite were the only youth who deserved to be Red Guards—the so-called bloodline theory.

“Surprisingly, much of this debate was initially encouraged and even subsidized by the state, which allowed Red Guard publishing houses and newspapers to print essays like Yu Luoke’s. The response was phenomenal. Yu’s publisher was so flooded with mail that the post office refused to deliver it, insisting that the publisher come by and pick up the sacks that arrived every day.

“Yang then goes on to show the uprising in underground culture that occurred toward the end of the Cultural Revolution, and the gradual dawning of China’s dissident movement during that decade. This was the result, in part, of the Red Guards’ experience of China’s poverty when they were exiled to the countryside. Most of the principal journals published in the Democracy Wall movement of 1978 and 1979—in which many documented their experiences during the Cultural Revolution on posters on the Xidan Wall in Beijing—were by former Red Guards, such as Wei Jingsheng, Bei Dao, Duo Duo, and Xu Wenli. These people were also a link to the 1989 Tiananmen protesters, who, although younger, echoed the desire of the Red Guard generation for martyrdom and grand gestures.

“As they grew older, the Red Guard generation engaged in new battles—over memory. These reflected many of the factional lines from the 1960s. The initial group of privileged Red Guards made themselves out to be pure of heart and ultimately victimized, and blamed the violence on the lower-class participants—often subsequently known as the “Rebels”—who joined later. Even today these divisions are crucial to understanding China. As an offspring of the first revolutionary generation, the current Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, runs the country as part of a coalescing aristocracy. In other words, the “bloodline” theory that Yu Luoke criticized is still very influential today.

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; photos, Ohio State University; Wiki Commons; History in Pictures blog; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021