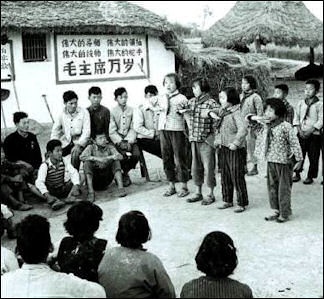

RED GUARD VIOLENCE

Red Guard looting a Russian church in Harbin

Fanatical students, calling themselves Red Guards, responded literally to Mao's call to "bombard the headquarters." Brainwashed by the Communist system and encouraged by Mao, they attacked people who they believed were hostile to Mao and his ideals. Barbara Demick wrote: The Red Guards persecuted their teachers. They smashed antiques, burned books, and ransacked private homes. (Pianos and nylon stockings were among the bourgeois items targeted.)

According to Associated Press: Though the Red Guards movement lasted for just over two years, it was involved in conflicts that claimed 230,000 lives across the country, according to official statistics released in the 1980s. The killing was particularly intense in the summer of 1967. A series of editorials in People’s Daily in early June 1967, inflaming and applauding student rebellion, turned the Red Guards into a nationwide phenomenon. In an editorial published on June 1, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece newspaper called for “sweeping away all the oxen, ghosts, snakes and spirits”, referring to the “reactionary academic authorities”. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

David McKenzie and Steven Jiang of CNN wrote: “The early enforcers were the Red Guards, a proxy army of children and young adults that violently struck out at anyone not toeing the Maoist line. Intellectuals, educators as well as artifacts were all targeted. A favorite method was to whip their elders with the heavy metal buckles on their leather belts.” “There was absolutely a top down approach to the violence and there is plenty of evidence that everything was very carefully planned," says historian Frank Dikötter. "There were constant messages going from the Party to the students. There was nothing spontaneous about it." [Source: David McKenzie and Steven Jiang, CNN, June 5, 2014]

Children stood by as Red Guards beat up their mothers for being "rightists." Neighbors informed on neighbors. violinists had their instruments and even fingers smashed by Red Guards. The accused sometimes had their jaws dislocated so they couldn’t speak in their defense and were forced to bow in front mobs that spit and screamed at them. There were also stories of people killing themselves by hammering nails into their skulls and corpses being mutilated in order to fit into coffins.

In their book "Mao’s Last Revolution" (2006), Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, say that Mao “unleashed a reign of terror in which the youth of China were . . . freed from parental and societal constraints . . . to perpetrate assault, battery and murder upon their fellow citizens to the extent their barely formed consciences permitted. The result was the juvenile state of nature, nationwide, foreshadowed in microcosm by Nobel prize-winner William Golding in Lord of the Flies.

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com ' CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com; REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; REVOLUTIONARY ENTHUSIASM, MANGOES AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION ENEMIES AND THE VICIOUS ATTACKS ON THEM factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su Amazon.com; “Civil War in Guangxi: The Cultural Revolution on China's Southern Periphery” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Victims and Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution “Victims of the Cultural Revolution: Testimonies of China's Tragedy” by Prof. Youqin Wang Amazon.com; “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin (New York Review Books, 2016) Amazon.com; “The Execution of Mayor Yin and Other Stories from the Great Cultural Revolution” by Chen Jo-his Amazon.com; “Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution” Amazon.com; "Voice from the Whirlwind" by Feng Jicai, a collection of oral histories from the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com

Red August and Early Red Guard Violence

In August 1966, after the start of the Cultural Revolution in May 1966, Mao gave his blessing to the Red Guards. This marked the start of a period so bloody it is often referred to as Red August. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: During this period, Red Guards ran rampant, killing more than 1,700 people in Beijing, including one of China’s most famous authors, Lao She. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

Sebastian Veg, history professor at the School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences in Paris, wrote: On August 5, 1966, Bian Zhongyun , the head of a Beijing girls’ school, died after being beaten and mishandled by Red Guards, in an incident that marked the beginning of “Red August.” Within a month, more than a thousand people were killed in Beijing, triggering a tide of violence that swept the whole country. Despite heated debates, the exact circumstances of Bian’s death remain contentious and shrouded in secrecy, no doubt compounded by the fact that at the time the daughters of several top state leaders attended the school. See Separate Article PROMINENT VICTIMS OF CULTURAL REVOLUTION ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

Veteran journalist Gao Yu, who was a university student in 1966, told the Associated Press her initial enthusiasm for the Cultural Revolution faded after fanatical young Red Guards raided her home and accused her father, a former ranking party cadre, of disloyalty to Mao. The violence of the era was impossible to avoid, she said. "I saw so many respected teachers in universities and high schools get beaten up," Gao said. "The movement wasn't so much a high-profile political struggle as a massive campaign against humanity." [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 16, 2016]

Zhang Lifan, a businessman who previously worked as an academic researcher, was a student at Tsinghua University High School. He told the New York Times: “Violence became widespread after August 18, 1966, and everywhere on the streets you could see people surrounded by crowds, bowed over and being beaten and struggled against. There were no standards. I saw a university student being beaten by a female Red Guard, and the people around told her to stop. And then this Red Guard said self-righteously, “Chairman Mao told me to beat him!” [Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“At Tsinghua High School I also saw students and teachers who were beaten up, or had their hair shaved off. At that time, all this was done by those who were “born red.” If you came from a bad family background, you didn’t qualify to join the Red Guards. My father was also beaten up by them, and he was covered in injuries, and they were afraid that if someone of his standing died that would be bad, so they sent him to Peking Union Medical College Hospital. But the hospital said they didn’t treat this kind of cow demon and snake spirit, so he wrote a note to Premier Zhou Enlai explaining that he’d been beaten up and the hospital wouldn’t treat him. Later he was taken into the emergency section for treatment, so it looks like Premier Zhou did send instructions.” Zhang Lifan’s father was Zhang Naiqi, a democratic politician who stayed in China after 1949 and was persecuted as a “Rightist” in 1957. He was again persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and died in a hospital in 1977. ~~

Carrying Out the Destroy the Four Olds Command

ransacking the Russian church in Harbin

In June 1966 middle schools and universities throughout the country closed down as students devoted all their time to Red Guard activities. Millions of these young students were encouraged to attack "counterrevolutionaries" and criticize those in the party who appeared to have deviated from Maoist thought. Driven by Mao’s edict to attack the “four olds,” gangs of Red Guards smashed up temples, destroyed artwork, and demolished libraries and cemeteries. The Communist Party cheered on the destruction, with the People’s Daily publishing a June 1 editorial exhorting cadres to “sweep away all monsters and demons!” A Red Guard leader who led raids on temples and other cultural treasures told the Christian Science Monitor: “Chairman Mao called for us to ‘Destroy the Four Olds’… and whatever Chairman Mao said, we did it right away.” [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016]

Karoline Kan wrote in Foreign Policy Magazine: “One day, the Red Guards received a “high command” that they should clean away all the “Four Olds” — old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. Their first step was to search people’s houses and confiscate any property that fit any of these broad categories; it could be a traditional painting, or a table. [Source: Karoline Kan, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 16, 2016 \=]

“One of the first targets was Lishui’s grandfather’s house. Terrified of severe punishment, the old man handed over his collection of books and paintings before those young people, including his own grandsons, would find them. The Red Guards piled the books and paintings and burned them. To show his sincerity and to avoid further punishment, my great-grandfather used the fire to boil water in front of the guards. Lishui also followed the other Red Guards to the west end of the village, where the village’s ancestral tombs lay. Dozens of the young guards started dug up tombs, broke coffins, and looted graves for jewelry, leaving the bones in the dry grass. Our family tombs weren’t spared. \=\

“But Lishui isn’t sorry about that either. He told me he followed guards to the tombs many times, but insists he did not take anything. “It was the leaders” who took the jewelry, he said, “although nobody knows what they did with the golden earrings and bracelets.” Lishui told me what they did was “not totally wrong,” because its intent was to convert the land so it could be used to plant grain. \=\

“Red Guards also banished Peking Opera, a once much-beloved art form, from the village. One day, after they’d finished destroying part of the local temple, Lishui and his fellow red guards broke into the village stock of opera stage settings and costumes and burned them. My uncle says he did think for a moment about how his father loved Peking Opera, and memories came back to him of old days when his father would take him onstage and let him practice reciting the lines of a small role. I never had a chance to ask my grandfather — once a frequent Peking Opera actor in the village, who until the last day of his life still held his radio to listen to famous opera performer Mei Lanfang — about how it felt to see his own son burning those cherished parts of his life. But I know my grandfather stopped singing Peking Opera for many years while the classic plays were banned and only eight “model operas” were permitted.” \=\

“Destroy the Four Olds” See CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com

Red Guards Attacks on People

Karoline Kan wrote in Foreign Policy Magazine: Over time, Red Guards turned from attacking physical objects to attacking people. My uncle says he could feel the turn happening, but he could not stop it, or stop himself. Whenever the Red Guards and the “people’s militias” chanted slogans outside, the young children of my family would run out and see what was going on. Then one day, the chanting stopped outside a nearby house, home to a lady who was more than 60 years old. Her husband used to do business when they were young, so the woman became “old white hair,” a target. The Red Guards found a pair of golden earrings hidden behind some photos frames. The old woman was dragged out and beaten by wooden sticks as thick as arms. [Source: Karoline Kan, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 16, 2016 \=]

“That same winter, my grandmother told me, a man surnamed Fu, one of the few landlords in the village, was found to have engaged in conduct before the founding of the People’s Republic of China that was “extremely guilty and evil.” So Red Guards dug a hole in the frozen river, tied Fu to a big stone, and pushed him into the hole. At first there was a cry and the sound of struggling in the water. Then everything was quiet except for the wind. \=\

“My great-grandfather, Lishui’s grandfather, was afraid for himself. Although he had already gambled away his property, it felt like hundreds of pairs of eyes were staring at his past: that of a young master, educated in Confucianism, who kept a concubine and was the village head during the nationalist Kuomingtang’s pre-Communist regime. He had negotiated with the occupying Japanese army when they passed through his village, giving them nice food and gifts in exchange for their mercy. \=\

“My mother once had a conversation with my great-grandfather. “They did not kill anyone when they lived in our village; isn’t that the result of my hard work?” she said he told her. “They killed so many people in our neighboring village. I don’t think I was wrong.” None of that mattered during the Cultural Revolution. My great-grandfather was forced to step on stage and accept criticism, wearing a “high hat,” which looked like a dunce cap, enumerating his crimes. Lishui worried about further retaliation against my grandfather, so Lishui visited his grandfather’s house to help him write self criticisms. \=\

“He was old and his eyes were diseased, so he told me his stories, and I wrote them down,” Lishui told me. “I also guided him to write what the Red Guards would like to hear. I remember a few lines: ‘I was born in 1899; at eight years old I started studying the Four Books and Five Classics taught by private teachers. I will reflect deeply and profoundly on my past.” But Lishui won’t blame Red Guards for his grandfather’s torment. “We were loyal, and we were following Chairman Mao’s guidelines,” Lishui said, “and what’s more important, we believed we were doing things that were good and meaningful.” He added that Chinese socialism was “facing great challenges from counterrevolutionists back then.” \=\

Violence by Red Guards

Yu Xiangzhen, a Red Guard, told CNN: “Our homeroom teacher Zhang Jilan was sent to the cowshed — a makeshift prison for intellectuals and other "bourgeois elements" — and suffered all kinds of humiliation and abuse. It wasn't until 1990 that I saw her again. During a class trip to the Great Wall, we made a formal apology to Ms. Zhang — then in her 80s — for what we had subjected her to. We asked what had happened to her in the cowshed. "It wasn't too bad," she said. "I was made to crawl like a dog on the ground." Hearing this, I burst into tears. I was not yet 14, and I had made her life a misery. She died two years after our apology. [Source: Yu Xiangzhen, CNN, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“At the height of the movement in 1968, people were publicly beaten to death every day during struggle sessions; others who had been persecuted threw themselves off tall buildings. Nobody was safe and the fear of being reported by others — in many cases our closest friends and family members — haunted us. At first, I was determined to be a good little revolutionary guard. But something bothered me. When I saw a student pour a bucket of rotten paste over our school principal in 1966, I sensed something wasn't right. I headed back to my dorm quietly, full of discomfort and guilt, thinking I wasn't revolutionary enough. ~~

“Later, when I was given a belt and told to whip an "enemy of the revolution", I ran away and was called a deserter by my fellow Red Guards. That same summer I caught a glimpse of Chairman Mao — our Red Sun — at Tiananmen Square, along with a million of other equally enthusiastic kids. I remember overwhelming feelings of joy. It wasn't until much later that I realized by blind idolization of Mao was a kind of worship even more fanatic than a cult. My father, a former war correspondent with state news agency Xinhua, was framed as a spy and denounced. But behind closed doors he warned my brother and I to "use our brains before taking action." "Don't do anything you will regret for the rest of your lives," he said. Slowly I began to Mao's wife Jiang Qing, who was a key leader of the Revolution, and I bowed grudgingly when my work unit had our mandatory daily worship ritual in front of the Chairman's image.” ~~

Targets of Red Guard Violence

Wu Qing, a human rights activist and retired professor, was teaching at a university in Beijing when the movement began. Her parents were prominent intellectuals. She told the New York Times: “I knew I would become a target because of my parents. My daddy served in the Kuomintang government and later was labeled a rightist. My mom had been labeled a reactionary writer, an unpunished rightist, and a running dog of the imperialists. [Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“But nothing happened to my parents until July or August 1966, when the Red Guards went to my home. My parents were forced to kneel on the ground for over three hours. At the time, my sister’s son was only a little over 2 months. The auntie was carrying him and she had to kneel down. It was feeding time, and they refused to let him be fed. They searched our home and took everything away. They were like robbers, they went in and took whatever they wanted. Then they locked the rooms. My parents stayed in a room smaller than 10 square meters. The students took away the cutting knives. They were afraid that my parents would commit suicide. ~~

“Then Minzu University held an exhibition. The Red Guards put all the things they had collected from the different families together and said they were all my parents’ stuff. They called it: “Exhibition of the Bourgeois Life of Wu Wenzao and Xie Bingxin.” There were pieces of gold, jade, silver and a lot of stuff. My parents had to stand outside of the exhibition every day for 10 days carrying a blackboard around their neck. ~~

“At the time, I was at my school. I couldn’t leave because there were struggle sessions against me. [Struggle sessions, when people were accused of political crimes, publicly humiliated and subject to verbal and physical abuse by a crowd, were a frequent occurrence during the Cultural Revolution] There were close to 80 in total. They said that because of my family background I could never love socialism and the Communist Party. The students couldn’t support me in public. But sometimes after the struggle sessions, they would come up to me when there was no one else around and apologize and say they were forced to do it. I never told my parents what happened to me. We never talked about it.” ~~

Cowsheds and Targets of Red Guard Violence

James Griffiths of CNN wrote: “ Party officials were by no means the only ones targeted by Red Guards and the newly empowered citizenry. Thousands of ordinary people — denounced as class enemies and counter revolutionaries — were abused, tortured and killed. Many were forced into "cowsheds” makeshift detention centers in which they were forced to perform manual labor and recite Maoist tracts and were regularly subject to beatings. "After a few months in the cowshed, I could feel my emotions being dulled and my thoughts growing more stupid by the day," writes Peking University professor Ji Xianlin in his memoir "The Cowshed.” [Source: James Griffiths, CNN, May 13, 2016 /^]

“His experiences during that time were a "dizzying descent into hell," Ji writes. But they were not uncommon. Ji and other, sometimes very elderly, professors and teachers were beaten, spat upon and tortured in rallies and criticism sessions that could last hours. In Daxing county, on the outskirts of Beijing, cadres ordered the extermination of all landlords and "other bad elements," Dikotter recounts. "Some were clubbed to death, others stabbed with chaff cutters or strangled with wire. Several were electrocuted. Children were hung by their feet and whipped.” More than 300 people were killed, with their bodies thrown into disused wells and mass graves./^\

“As the country plunged into chaos, Mao's fervor increased. "It's a game that Mao is playing," Dikotter says. "He incites students to attack teachers, then unleashes the population on the Party itself, then asks the army to step in, before you know it people are literally fighting each other.” According to Dikotter, Mao created a frenzied cycle "where people are endlessly trying to prove their allegiance to the Chairman.” /^\

In a review of “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin, Zha Jianying wrote in the New York Review of Books: “At the center of the book is the cowshed, the popular term for makeshift detention centers that had sprung up in many Chinese cities at the time. This one was set up at the heart of the Peking University campus, where the author was locked up for nine months with throngs of other fallen professors and school officials, doing manual labor and reciting tracts of Mao’s writing. [Source: Zha Jianying, New York Review of Books, January 26, 2016 *]

“The inferno atmosphere of the place, the chilling variety of physical and psychological violence the guards daily inflicted on the convicts with sadistic pleasure, the starvation and human degeneration—all are vividly described. Indeed, of all the memoirs of the Cultural Revolution, I cannot think of another one that offers such a devastatingly direct and detailed testimony on the physical and mental abuse an entire imprisoned intellectual community suffered. After reading the book, a Chinese intellectual friend summed it up to me: “This is our Auschwitz.” *\

Confessions of Violence and Killing by a Red Guard

Adrian Brown of Al Jazeera wrote: “For many Chinese people, the Cultural Revolution remains a taboo subject, especially among those of 65 years of age or older. But occasionally - just occasionally - you come across someone who is prepared to confess to the very worst of crimes.For the past three decades Wang Yiju has run a successful riding school and stud farm outside Beijing. But it is his life in the previous two decades that he has agreed to discuss on this bright spring day. [Source: Adrian Brown, Al Jazeera, May 13, 2016]

In clinical dispassionate language he describes how he became sucked into the anarchy going on all around him. "At first we were reluctant to beat others, but someone would criticise us … Finally we loved to beat others. Killing became very common at the time when people treated fighting as fun. It was natural to kill people in such circumstances," said Wang.

On August 5, 1967, Wang became a killer. His victim was another student from a rival faction. "I beat the back of his head with a rod. The rod was thick and hard, very long about 1.6 meters long, similar to the handle of a big hoe … I beat his head and broke the back of his skull. The police later told me that one blow was enough to kill a person with such a rod and with my power." Wang was arrested, but later freed after the family of the dead student forgave him. He finally made a full apology in 2008 and is urging others who killed to confess.

"Few people will understand what the Cultural Revolution was if we all hold back the truth," said Wang. "I think the true nature of that time is made up of memories and stories of the participants who clearly know what happened. Someone has to tell the truth, or our generation will have failed. That is why I spoke out."

Red Guards Attack My Sister and Father

Zehao Zhou wrote in USA Today: “Two enemies of the state lived under the same roof as me: my sister and my father. My sister’s crime was being a school principal, which qualified her as a “capitalist roader.” My father’s crime was his experience as a World War II veteran who served with the Flying Tigers in China, which qualified him as a “historical counterrevolutionary.” [Source: Zehao Zhou, USA Today Network, May 14, 2016]

My sister initially went into hiding, only to return to Shanghai on a day slated as a citywide "humiliation parade" for school principals. The Red Guards herded my sister, who was disabled, and hundreds of other school principals for miles on foot in downtown Shanghai. No evidence was necessary. Educators deserved the iron fists of the Red Guards and proletarian dictatorship, according to the Red Guards. Zehao Zhou of Manchester Township, Pa., is an assistant

My father’s wartime service with the Americans made him an easy target for Red Guards. Yet, despite being gravely ill and defenseless, he somehow managed to turn aside the assault. As the Red Guards approached his sick bed, my father said in a calm voice, “I am sick with tuberculosis. It is contagious.” Hearing that, the Red Guards, who recited “Fear neither hardship nor death” from Mao’s Little Red Book every day, turned tail and fled. While Dad dodged that assault, the cumulative effect of years of persecution caught up with him. He died shortly after that at age 49, and we were not even allowed to mourn this “enemy of the state.”

Bloody Battles Between the Red Guard Factions

barricade from a battle between Red Guard factions

Violence and death caused during the Cultural Revolution is now believed to have been more widespread than previously thought. Scholars originally thought that most of the violence ended with the suppression of the Red Guard and rebel organizations in 1968. Austin Ramzy wrote in the New York Times: Red Guards targeted the authorities on campuses, then party officials and “class enemies” in society at large. They carried out mass killings in Beijing and other cities as the violence swept across the country. They also battled one another, sometimes with heavy weapons, such as in the city of Chongqing. The military joined the conflict, adding to the factional violence and killing of civilians. The pogroms even included cannibalization of victims in the southern region of Guangxi. [Source: Austin Ramzy, New York Times, May 14, 2016

During one phase of the Cultural Revolution factory fought factory, school fought school and Red Guard factions fought each other over the honor of being the purest Maoists. One man in northeast China — who was 13 when he joined the Red Guards and said that "for a teenager" the Cultural Revolution "was very exciting”— described Red Guard factional fighting that began as a clash over ideals, escalated to struggle for local power, and ended up as a "revenge fest." "In the beginning, the two sides used sticks and clubs and spears," he told the Washington Post. "But then they grabbed hunting rifles, and it kept escalating. Our organization even used artillery." [Source: Daniel Southerland, Washington Post, July 18, 1994]

Associated Press reported: While seizing power from the bureaucrats, rebels around the country also ended up firing at each other. When Beijing ordered rebels to return weapons to the army two years later, 2.13 million rifles and more than 10,000 artillery pieces were reclaimed across the country. Scholars now believe that two little-known and little-studied campaigns of the Cultural Revolution — the "Purification of the Class Ranks" (1968-70) and the campaign against "May 16 Elements" (1968-69) — were among the bloodiest events of the Cultural Revolution. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

John Gittings wrote in China Beat: ""The generally accepted view that the factional divisions among the Red Guards reflected the social and political inequalities of Mao-era China — in other words that some factions represented conservatives whose families belonged to the Party, the bureaucracy and other privileged strata, while the more radical factions were led by students from families with no social advantages who felt excluded from the dominant system. A variant of this analysis saw the main division as one between conservative networks of party members and political activists and radical groupings of those who had previously been excluded from these network ties. [Source: John Gittings, China Beat, March 31, 2010]

See Separate Article: FACTIONAL DIVISIONS IN TIBET DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com

Red Guard Factions Fight in Beijing

John Gittings wrote in China Beat: "In 1968, Red Guard factions battled on another at Beijing’s Qinghua University. Red Guards told the writer and historian William Hinton about how the struggle on the campus in April of that year escalated from stone slingshots and wooden spears to revolvers and hand grenades. One group welded steelplates onto the body of a tractor to convert it into a tank. Ten students were killed and many more badly injured in the next three months till July 1968 when Mao Zedong finally sent in groups of local workers, backed by the army, to restore order. [Source: John Gittings, China Beat, March 31, 2010]

"An unrestrained wave of violence began at the end of July 1968 as work teams were withdrawn from school and college campuses. High-school students seized party secretaries, principals, teachers andclassmates and subjected them to violent beating. . . . At least eight high-school party secretaries, principals, or vice-principals were murdered or committed suicide — the first such murder was that of Bian Zhongyun, deputy principal of the Beijing Normal Girls’ High School. (The story of Bian’s murder has now been told in a remarkable film, "Though I am Gone" ("Wo Sui Siqu") by the independent Chinese film-maker Hu Jie, largely based on interviews with her husband who at the time with exceptional courage took photographs of her corpse and the circumstances of her death. The film cannot be shown in China but may be found on YouTube.)

"However the violence escalated after Mao’s first Red Guard rally even more terrifyingly. Walder records that in the following month more than 114,000 homes of those identified as bad classes were searched, typically in violent assaults by Red Guards, for evidence of bourgeois ideology such as foreign currency, books, paintings etc.In his book "Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement" Andrew G. Walder wrote: “In the Western district, the books, paintings, scrolls, and other items confiscated from 1,061 homes were set ablaze and burned for eight days and nights. During this period 77,000 people were expelled from their homes in the urban and inner suburban districts. The violence crested during the last week of August, when an average of more than 200 people were dying every day. The official Beijing death toll for the month after August 18 was 1,772.”

Red Guard Violence in Chengdu and Chongqing

Daniel Southerland wrote in the Washington Post: "The worst clashes took place in the Sichuan, Province where rival groups of Red Guards fought "house to house street battles" with guns, rockets and tanks looted from the People's Liberation Army. Chengdu was where the first Red Guard clashes of the Cultural Revolution began, first around a cotton mill and then at a fighter-plane factory. In May 1967, conservative and radical factions in Chengdu, a center for defense industries, battled with automatic rifles, mortars recoilless rifles and rocket propelled grenade launchers. One side obtained weapons from local militias and People's Liberation Army units. in the summer of 1967, PLA troops shot dead a many as a thousand Red Guards members who protested the arrest of a faction leader. [Source: Daniel Southerland, Washington Post, July 18, 1994]

Chengdu was the site of brutal street fights between factions of Red Guards. Zhang Jingyan, a retired art-history professor in Chengdu who was 12 when the Cultural Revolution broke out. told The New Yorker,"I went to watch, and it was terrifying. I watched people being thrown off buildings," she said. "I couldn't move or run away. I was completely frozen by it. And then I felt ashamed: Why don't I have more class consciousness? These are the enemies of our class! How come other people are capable of hitting them, and I'm not?" But Professor Zhou Daming, who was sent to labor in the fields at 16, said the new exercise was completely different. "We had barely graduated from high school. We did not even have the most basic knowledge about many things. The experience was good in that it taught me to 'eat bitterness'. Everything that came afterwards did not seem challenging or impossible anymore. I think this experience — especially now that I am doing social study work — broadened my view of society."

During the period of armed violence in Chongqing in 1967 Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, Red Guards fought bloody battles with knives, pistols, machine guns, and even floating artillery platforms from which they bombarded their enemies while sailing on the Yangtze River.” In his book, The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China”, Guobin Yang " makes clear, these battles were reenactments of the films and stories they had been shown and told about the revolution of the 1930s and 1940s. The Red Guards sent themselves off to battle with slogans drawn from war movies, and wrote moving eulogies for the hundreds killed that echoed the rhetoric of the Communist wartime myths.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

Associated Press reported: In Chongqing, Zheng, who was studying electrical engineering, saw his “humble” principal targeted as the local authorities tried to fill the quota of “two to three capitalist roaders at each university”. The quota was passed down by the provincial authorities in Sichuan, which then governed Chongqing, following a directive from Beijing. Zheng’s principal committed suicide in custody...Two months after the start of the Cultural Revolution, Mao ordered the withdrawal of party working groups that had been guiding the campaign. In a document issued in August of that year denouncing traditional top-down purges, Beijing said “[We] must trust and rely on the people ... don’t be scared of chaos.”A week after that document was issued, thousands of people in Chongqing, more than 1,400km from Beijing, staged a massive protest against the city government, something rarely seen before. Many of the protesters, including Zheng, who said he “exploded like a volcano” after hearing of the death of his principal, became the city’s first Red Guards. They named themselves after the date of the protest – 815. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

Red Guard Versus Red Guard Violence in Chongqing

Associated Press reported: Zheng Zhisheng, a 25-year-old Chongqing University student, turned and waved to two fellow Red Guards sitting in the back of the van. As had been agreed, they slammed their rifle stocks into the heads of their two captives, members of a rival Red Guard faction, time and again. There were no screams: the captives were already badly injured and unconscious after successive beatings by Zheng’s faction on August 18, 1967, at the height of the armed conflicts early in the Cultural -Revolution. Zheng told the driver to take a longer route to the hospital, so they could take their time. “I don’t have the guts to kill, I thought, but I could have them killed at the hands of others,” Zheng said in a recent interview. The captives were dead when they arrived at the hospital. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

It was a time when killing became normal, as universities, factories and cities around China turned into battlefields in what Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong called an “all-out civil war”, with all the factions involved vowing to protect Mao’s revolutionary line. The southwestern city Chongqing,, home to a strong military presence guarding against an increasingly hostile Soviet Union, was among the worst-hit cities. As in most cities in China at the time, rebellious workers and students in Chongqing split into two major factions, each accusing the other of being “capitalist roaders”. At first it was debates and big-character posters, but sticks and rifles soon followed. As Beijing condoned such fights, and even openly urged local army units to support them, Red Guards and other rebels in Chongqing ransacked local arsenals and used rifles, tanks, cannons and gunboats to fire on neighbors and colleagues who were members of the opposing faction. [Source: Associated Press, June 9, 2016]

Li Musen, a technician at Chongqing’s artillery shell factory, was one of the top commanders of the “rebel until the end” Red Guard camp, the 815 faction’s rivals. “I did pretty well in the conflicts,” said Li, who was 28 when the Cultural Revolution broke out. “I put my life in danger to win the position.” Li fought nine battles before signing a truce to end the conflict. As well as commanding others, he loaded and fired artillery shells in some battles. “When I commanded the shelling, I wished we could kill as many as possible with each shell ... we all felt like we were guarding Mao’s revolutionary line,” Li said. “We were not afraid of bleeding or dying.”

barricades from Red Guard faction fighting

Numerous cadres, intellectuals and students labeled enemies of the party had been purged in the 17 years since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, but Mao wanted something different in 1966. On his return to Beijing from a sojourn in the south in July, two months after the start of the Cultural Revolution, Mao ordered the withdrawal of party working groups that had been guiding the campaign. In a document issued in August of that year denouncing traditional top-down purges, Beijing said “[We] must trust and rely on the people ... don’t be scared of chaos.”

A week after that document was issued, thousands of people in Chongqing, more than 1,400km from Beijing, staged a massive protest against the city government, something rarely seen before. Many of the protesters, including Zheng, who said he “exploded like a volcano” after hearing of the death of his principal, became the city’s first Red Guards. They named themselves after the date of the protest – 815.

Reigning in the Violence During the Cultural Revolution

Yiching Wu told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “The disorder caused by mass insurgencies from below and paralyzing power conflicts at the top created a crisis. The nation was on the brink of anarchy. For example, some young radicals, invoking the historical example of the Paris Commune, claimed that China’s “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” would have to be toppled in order to establish a society in which the people can self-govern. Mao decided the crisis would have to be resolved. Quashing the restless rebels, the revolution cannibalized its own children and exhausted its once explosive energy. The demobilization of freewheeling mass politics in the late 1960s helped to restore the authority of the party-state, but also became the starting point for a series of crisis-coping maneuvers which eventually led to the historic changes in Chinese society and economy a decade later. [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook, Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016]

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “Rising violence later compelled party leaders to send in the People's Liberation Army to reassert control as many government functions were suspended and long-standing party leaders sent to work in farms and factories or detained in makeshift jails. To put a stop to the violence and chaos, millions of students were dispatched to the countryside to live and work with the peasantry, among them current President Xi Jinping, who lived in a cave dwelling for several years in his family's ancestral province of Sha'anxi. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 16, 2016 =]

“Much of the country was on a wartime footing during the period, with Mao growing increasingly feeble and tense relations with former ally the Soviet Union breaking out into border clashes. Radicals allied with the so-called "Gang of Four," consisting of Mao's wife Jiang Qing and her confederates, battled with those representing the party's old guard, who were desperate to end the chaos in the economy, schools and government institutions.” =

Red Guard Who Isn’t Sorry

Red Guards ransack church

Karoline Kan wrote in Foreign Policy Magazine: Lishui is the nickname for my uncle, a farmer who has lived all his life in the suburbs of Tianjin, a big city in northeastern China. Whenever people talk about Lishui, my mother’s older brother, they always say: “Lishui is a nice guy, honest, always in a good mood.” As a young child, when I heard him coming to visit, I would rush out of the house, climb onto his shoulders, and pull his ears. The more I think about Lishui, the more I am confused by the fact that he was a Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution...Most confusing to me is the fact that my kind and honest uncle says he doesn’t regret a single thing he did — not even today, when the Cultural Revolution is widely acknowledged both outside and within China as a massive historical mistake. [Source: Karoline Kan, Foreign Policy Magazine, May 16, 2016 \=]

“After the Cultural Revolution ended, “Lishui found himself a farmer once again. A photograph from that time shows him young and happy in a white shirt, green army trousers, and an army hat. Things have not gotten better for Chinese socialism, or for my uncle. He is bitter that China has cast off the values he fought for and for which he sacrificed his youth, the kind of socialism where the workers and farmers like him were the masters of their country. In his youth, Lishui believed in a socialism in which there were no classes. He remains proud that he was what he calls a “good student” of Chairman Mao. (During the Great Leap Forward, a disastrous and famine-inducing policy Mao implemented in the late 1950s to spike economic production, Lishui was one of the children who pushed their parents to donate their iron tools, including farming implements, so they could be melted down to make steel. Even today, he never addresses Mao Zedong by name, but always as “Chairman Mao.”) \=\

“But in today’s highly unequal China, it seems, the joke is on Lishui. My uncle now lives as a farmer in the Tianjin suburbs, and says he has nothing more than the $15 pension he receives each month from the government. He still likes to talk politics. “The aim of the Cultural Revolution was good,” Lishui insists. “Our society now lacks some of the positive spirit of the Cultural Revolution.” Lishui is serious about that contention. “During the Cultural Revolution, nobody dared to abuse their power like today,” he told me. “Farmers and workers were like the real masters of the country. Look at today: officials are the lords, and this country is full of capitalists. I dare say 99 percent of the village officials in China,” some of which are chosen via a quasi-democratic process, “gave bribes to get themselves elected.” \=\

“Around early 2013, when Chinese president Xi Jinping started a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, his portrait appeared on my uncle’s wall. Lishui was excited, and in conversation he used to link the campaign to an earlier Mao-led movement in 1963, the Four Cleanups, meant to remove “reactionary” elements from Chinese politics. But to Lishui’s disappointment, a new Cultural Revolution hasn’t followed. On my most recent visit to my uncle’s house, Xi’s portrait no longer adorned the wall. Lishui is still waiting.” \=\

Red Guards Opposed to Violence

In his book "Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement" Andrew G. Walder argues that substantial groups in the Red Guard movement in Beijing — perhaps the majority — were actually opposed to the violence and many said so. They organized Red Guard picket corps which sought to curtail violence and provide discipline to an anarchic and rapidly growing movement. The Western District Picket Corps, an alliance of 50 Red Guard groups from more than 40 schools, announced that “In the Cultural Revolution from this point forward it is absolutely forbidden to beat people, absolutely forbidden to physically abuse them either openly or in a disguised manner; absolutely forbidden to humiliate people, absolutely forbidden to extract forced confessions. . . . Kneeling, lying flat, bending at the waist, carrying a heavy weight, standing for long periods, keeping hands raised for long periods, keeping heads bowed for long period, etc., all are open or disguised forms of physical abuse and not methods of struggle that we should use.” [Source: John Gittings, China Beat, March 31, 2010]

Far from their consciences being barely formed, these young Red Guards showed a genuine sense of ethical judgement. Their members were expected to serve the people and gain their trust by non-violent means. The Red Guards at Qinghua University had issued a series of appeals for non-violence from the beginning of August. Their first appeal was initially welcomed by Mao himself who had it circulated to delegates of the Party plenum.

We may infer from Walder’s account (though he does not pursue the argument) that the violent course taken by the Red Guards was not inevitable. Instead of being egged on by the ultra-left leadership, the students could have been steered to pursue a largely non-violent cultural revolution against privilege and bureaucracy — natural targets in China then and indeed now. Even after the violence erupted in August, the picket corps still represented the majority of student opinion, backed by Premier Zhou Enlai who held a series of meetings attempting to persuade the Red Guards to exercise restraint.

So why did reason not prevail? Walder explains that the calls to curtail violence ran directly counter to the views of the CCRG. Jiang Qing had given an early nod countenancing violence on July 28, telling high school Red Guards that we do not advocate beating people, but beating people is no big deal. Later, Mao told the Politburo Standing Committee that I do not think Beijing is all that chaotic. . . . now is not the time to interfere. . . Taking his cue from Mao, Xie Fuzhi, minister of public security, set the official line: I do not approve of the masses killing people, but the masses — bitter hatred toward bad people cannot be discouraged, and it is unavoidable. The local police and army were ordered not to intervene when Red Guards were on the rampage.

Walder now shows that not only did many Red Guards dislike the violence but that — after the first protests by the picket corps had been stifled — a minority of independent-minded dissidents began to develop a new critique of the ultra-left CCRG leadership which identified the taste for violence as one of that leadership’s unprincipled weapons. Alone among students at this point in Chinese history, says Walder, they had a realistic view of what was actually taking place, while the [officially approved] “rebels” were conforming to CCRG authority and wrapping their actions in a fantasy language of conspiracy and rebellion.

Walder argues that the factional struggles of those times did not reflect social conflict but were the product of authoritarian political structures. He called the dominant Red Guards radical bureaucrats, This may be true in Beijing but it does not necessarily explain factionalism elsewhere in China.

John Gittings is an author and research associate at the School of Oriental & African Studies. His most recent book is The Changing Face of China: From Mao to Market (Oxford, 2005)]

Book: "Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement" by Andrew G. Walder (Harvard University Press, 2009)

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; photos, Ohio State University; Wiki Commons; History in Pictures blog; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021