CULTURAL REVOLUTION

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76), as the Cultural Revolution was officially known, was a 10-year social political movement initiated to strengthen Maoism in China by eliminating capitalist, feudalistic and cultural elements through an ideological campaign aimed at reviving revolutionary spirit and purging the country of "impure" elements. An internal power struggle quickly spilled over into all facets of the society. Destruction and violence of unspeakable proportions ensued. Young Chinese people were sent to the countryside to learn from the hard life of the peasants. Millions of people were persecuted and killed during Mao's rule.

The Cultural Revolution was one of the most turbulent periods in Chinese history. It continued until Mao’s death in 1976, but was most intense from 1966 to 1969. During that time there was fighting between factions and attacks on teachers, bureaucrats, intellectuals, scientists and anyone suspected of having connections with capitalists or foreigners. The party structure collapsed in some cities, and from January 1967 through mid-1968 was replaced by Revolutionary Committees. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The Cultural Revolution has been described as a disastrous combination of the opposite “a command economy and anarchic politics. About 36 million people were persecuted and anywhere from 750,000 to 1.5 million killed. Cultural Revolution-era policies responded with public deprecation of schooling and expertise, including closing of all schools for a year or more and of universities for nearly a decade, exaltation of on-the-job training and of political motivation over expertise, and preferential treatment for workers and peasant youth. Educated urban youth, most of whom came from "bourgeois" families, were persuaded or coerced to settle in the countryside, often in remote frontier districts. Because there were no jobs in the cities, the party expected urban youth to apply their education in the countryside as primary school teachers, production team accountants, or barefoot doctors; many did manual labor. The policy was intensely unpopular, not only with urban parents and youth but also with peasants and was dropped soon after the fall of the Gang of Four in late 1976. [Source: Library of Congress]

Benjamin Carlson of AFP wrote: Launched by Mao in 1966 to topple his political enemies after the failure of the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution saw a decade of violence and destruction nationwide as party-led class conflict devolved into social chaos. Teenage Red Guards beat teachers to death for being "counter-revolutionaries" and family members denounced one another while factions clashed bitterly for control across the country. But the Communist Party — which long ago decided that Mao was "70 percent right and 30 percent wrong" — does not allow full discussion of events and responsibility.” [Source: Benjamin Carlson, AFP, May 11, 2016]

Mao launched the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” as a way of attacking his enemies within the Party leadership, most notably President Liu Shaoqi (1898-1969) and Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997).On May 16, 1966, the Chinese Communist Party released a document expressing concern that bourgeoisie and counterrevolutionaries were trying to hijack the party. The May 16 Notification, as it became known, is cited by many as the spark the Cultural Revolution. The two year period between May, 1966 and the summer of 1968 was the most active and radical period of the Cultural Revolution. The period between 1968 and 1976 was a period of recovery when members of the Red Guard were re-educated and some assemblage of order was restored. Today the Cultural Revolution is officially known in China as "Ten Years of Chaos" or "Ten Years of Calamity."

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org Great Leap Forward: University of Chicago Chronicle chronicle.uchicago.edu ; Mt. Holyoke China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Wikipedia ; Industrial Planning Video You Tube ; Death Under Mao: Uncounted Millions, Washington Post article paulbogdanor.com ; Death Tolls erols.com ; Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; REVOLUTIONARY ENTHUSIASM, MANGOES AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION ENEMIES AND THE VICIOUS ATTACKS ON THEM factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; SURVIVING AND LIVING THROUGH THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: DEATH TOLL, FIGHTING AND MASS KILLING factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; FACTIONAL DIVISIONS IN TIBET DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; ATTACK ON JOKHANG TEMPLE AND END OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN LHASA factsanddetails.com; BACK TO THE COUNTRYSIDE MOVEMENT OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; WINDING DOWN AND END OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND TRIAL OF THE GANG OF FOUR factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RESEARCHING AND WHITEWASHING THE THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION NOSTALGIA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su Amazon.com; “Civil War in Guangxi: The Cultural Revolution on China's Southern Periphery” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982"by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com; Victims and Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution “Victims of the Cultural Revolution: Testimonies of China's Tragedy” by Prof. Youqin Wang Amazon.com; “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin (New York Review Books, 2016) Amazon.com; “The Execution of Mayor Yin and Other Stories from the Great Cultural Revolution” by Chen Jo-his Amazon.com; “Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution” Amazon.com; "Voice from the Whirlwind" by Feng Jicai, a collection of oral histories from the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com

Major Figures in the Cultural Revolution

Austin Ramzy wrote in the New York Times: Mao Zedong is the key figure. “The Cultural Revolution began at his behest, and factions battled in his name. He called on Red Guards to “bombard the headquarters,” which was seen to mean other top leaders like Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. Liu Shaoqi, China’s president, relaxed collectivization to undo some of the damage of the Great Leap Forward and became the leading target of Cultural Revolution attacks. He died in custody in 1969, after two years of abuse and denial of medical treatment. [Source: Austin Ramzy, New York Times, May 14, 2016]

“Zhou Enlai, the second-most senior leader, managed to survive by showing loyalty to Mao. Many in China credit him for curbing the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, but he could act on important matters only with Mao’s approval. His death from cancer in 1976 touched off protests and widespread mourning. Deng Xiaoping was a People’s Liberation Army veteran and leader who was twice purged during the Cultural Revolution. He returned to power after Mao’s death, pushing drastic economic reforms in the next decade.

“Jiang Qing, a former actress, was able, as Mao’s wife, to claim authority during the Cultural Revolution, particularly over the arts. She was the leading figure of the Gang of Four, radicals who reached the peak of political power during the Cultural Revolution. She was arrested after Mao’s death and committed suicide in 1991.

“Lin Biao was the leader of the People’s Liberation Army and played a crucial role in promoting the cult of Mao, including ordering the compilation of the “Little Red Book” of the chairman’s sayings. Lin was designated Mao’s successor, but died in 1971 when his plane crashed in Mongolia. He was apparently trying to flee after learning that Mao was turning against him, but the circumstances of his death remain unclear.”

Ideas and Forces Behind the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution was a movement that intended to create a new society by destroying traditional beliefs, customs and thinking, by purging "revisionist thought" and by crushing perceived enemies of the Communist Party. During the movement Mao saw knowledge as power and believed that by subverting it he could eliminate his greatest threats. Austin Ramzy wrote in the New York Times: The movement was fundamentally about elite politics, as Mao tried to reassert control by setting radical youths against the Communist Party hierarchy. But it had widespread consequences at all levels of society. Young people battled Mao’s perceived enemies, and one another, as Red Guards, before being sent to the countryside in the later stages of the Cultural Revolution. Intellectuals, people deemed “class enemies” and those with ties to the West or the former Nationalist government were persecuted. Many officials were purged. Some, like the future leader Deng Xiaoping, were eventually rehabilitated. Others were killed, committed suicide or were left permanently scarred. Some scholars contend that the trauma of the era contributed to economic transition in the decades that followed, as Chinese were willing to embrace market-oriented reforms to spur growth and ease deprivation. [Source: Austin Ramzy, New York Times, May 14, 2016]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “To Mao the revolution had to be a permanent process, constantly kept alive through unending class struggle. Hidden enemies in the party and intellectual circles had to be identified and removed. Conceived of as a "revolution to touch people’s souls," the aim of the Cultural Revolution was to attack the Four Olds — old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits — in order to bring the areas of education, art and literature in line with Communist ideology. Anything that was suspected of being feudal or bourgeois was to be destroyed. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

In 1966 Mao had called on the student Red Guards to rebel against "reactionary" authorities. His aim was to reshape society by purging it of bourgeois elements and traditional ways of thinking. Millions of people were arrested and terrorized by the Red Guards, the Cultural Revolution’s paramilitary youth organization. Those arrested were forced to endure brutal “struggle sessions,” where they were tortured and humiliated in public. By the summer of 1968 the country had become engulfed in fighting, as Red Guard factions competed for power. By the time the revolution ended in 1976, possibly as many as three million people had been killed. The violence and persecution during the revolution was catastrophic, and the decade arguably ranks as one of China’s darkest periods.

Tania Branigan wrote in the Guardian: “The theory was that creative destruction would eradicate old habits and ideas, transforming a struggling country. More urgently, the disastrous Great Leap Forward and Khrushchev's fall in the Soviet Union impelled Mao to see off rivals and critics. His heir apparent Liu Shaoqi was one of many to die in disgrace. The violence shook every strata of society and rippled out to the farthest corners of the country. Teenagers and youths were encouraged to attack fellow citizens. More than one observer has compared the anarchy to Lord Of The Flies.”

John Gittings wrote in China Beat, "Outside China there is a tendency to write off the whole affair as culminating proof that Mao was a Monster. In "Mao: The Unknown Story", Jung Chang and Jon Halliday claim that Mao from his youth had taken a delight in bloodthirsty thuggery, that he had wished to terrorise the nation by unleashing the Red Guards, and that he took pleasure in watching films of torture and murder committed by them. These assertions are part of a disappointingly one-dimensional picture of Mao (it ignores, among other things, his extensive theoretical speeches and writings) but which seems to resonate with many readers. This view has been criticized by a number of serious scholars, both Chinese and Western: their views have been brought together in Was Mao Really a Monster?" (Routledge, 2010) edited by Gregor Benton and Lin Chun. [Source: John Gittings, China Beat, March 31, 2010]

Causes of the Cultural Revolution

backyard furnaces from the Great Leap Forward

Nicholas Haggerty wrote in Commonwealth: “The two theories on the origins taught in American college classrooms are that: 1) the Cultural Revolution was Mao's Machiavellian scheme to regain the power he had lost after the Great Leap Forward by mobilizing the populations with which he was popular; and 2) the result of Mao’s sincere concern that the revolution was dying. [Source:Nicholas Haggerty, Commonwealth, May 9, 2016 ^/^]

On these theories, Professor Yiju Huang at Fordham University said: “These two accounts are not contradictory. The latter though is more of a political understanding that can be traced back to the intense global interest in the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s. The Parisian intelligentsia’s profound infatuation with Maoism comes to mind here. Maoism represented an alternative path not only from the universality of the capitalist mode of history but also from the ossified fate of Stalinist Russia.

“Some historians, like Maurice Meisner, take the "long view" towards the Chinese revolution, and place their analytical focus on 1949 rather than events of the 1960s. Between 1949, when the Communists took power, and 1976, when Mao died, life expectancy rose tremendously, literacy rates rose tremendously, which these historians argue provided the groundwork for China’s economic miracle.” ^/^

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The best formula for a revolution seems to involve turning youth against its elders, rather than turning one class against another. Not all societies have a class system so clear-cut that class antagonism is effective. On the other hand, Chinese youth, in its opposition to the "establishment," to conservatism, to traditional religion, to blind emulation of Western customs and institutions, to the traditional family structure and the position of women, had hopes that communism would eradicate the specific "evil" which each individual wanted abolished. Mao and his followers had once been such rebellious youths, but by the 1960's they were mostly old men and a new youth had appeared, a generation of revolutionaries for whom the "old regime" was dim history, not reality. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1977, University of California, Berkeley]

In the struggle between Mao and Liu Shaoqi, which became increasingly apparent in 1966, Mao tried to retain his power by mobilizing young people as "Red Guards" and by inciting them to make the "Great Proletarian Revolution." The motives behind the struggle are diverse. It is on the one hand a conflict of persons contending for power, but there are also disagreements over theory: for example, should China's present generation toil to make possible a better life only for the next generation, or should it enjoy the fruits of its labor, after its many years of suffering? Mao opposes such "weakening" and favours a new generation willing to endure hardships, as he did in his youth. There is also a question whether the Chinese Communist Party under the banner of Maoism should replace the Russian party, establish Mao as the fourth founder after Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, and become the leader of world communism. However, Chinese youth was summoned to take up the fight for Mao and his group, forces were loosed which could not be controlled.

Cost of the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution was a horrible period in Chinese history. Intellectuals were paraded through streets with dunce caps; Muslims were forced to slaughter pigs; and Tibetan monks were taken from their monasteries and put to work in labor camps. Confucius statues that stood for centuries were labeled as decadent and torn down; priceless Ming vases were shattered; and thousand-year-old Buddhist murals were vandalized beyond repair. At the height of the Cultural Revolution, the People's Daily ran the headline: "There is Chaos Under Heaven’the Situation Is Excellent."

Looting of church by Red Guards

Adrian Brown of Al Jazeera wrote: “You would be hard pressed to find someone in China who has family, friends or relatives who were not touched in some way by the Cultural Revolution. The father of China's President Xi Jinping was persecuted and the young Xi was forced into hiding in the countryside. It was a mass brainwashing - collective madness in which those with the most sadistic streaks flourished - and many did. No wonder so few people are prepared to really talk about what happened; to admit their guilt, to express their sorrow. It is as if one is trying to talk to Cambodians about life under the Khmer Rouge. “There are still no official figures on how many people were killed or purged in China during the Cultural Revolution. But some historians say the number of dead could be as high as two million - still less than the millions who died during the famines blamed on Chairman Mao's disastrous policies in the late 1950s. [Source: Adrian Brown, Al Jazeera, May 13, 2016]

Schools were closed; houses were invaded; work places became battlegrounds; mini-civil wars broke out throughout the country; and people were turned into the police by their friends, and tortured and killed for reading books in English. Entire families were massacred for being from "bad class" backgrounds. The violence and chaos drove neighbor against neighbor, destroyed the economy, drove the country to the brink of famine and forced a generation of intellectual to work in the countryside. Nearly every Chinese city dweller today who was alive then knows of a friend or relative that have was beaten, harassed or driven to suicide during the Cultural Revolution. In Cambodia, the Cultural Revolution inspired the Khmer Rouge.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: By the time the Cultural Revolution sputtered to a halt, there were many ways to tally its effects: about two hundred million people in the countryside suffered from chronic malnutrition, because the economy had been crippled; up to twenty million people had been uprooted and sent to the countryside; and up to one and a half million had been executed or driven to suicide. The taint of foreign ideas, real or imagined, was often the basis for an accusation; libraries of foreign texts were destroyed, and the British embassy was burned. When Xi Zhongxun—the father of China’s current President, Xi Jinping—was dragged before a crowd, he was accused, among other things, of having gazed at West Berlin through binoculars during a visit to East Germany.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, May 6, 2016]

No one knows exactly how many died, but estimates range from hundreds of thousands to 20 million. Hu Yaobang, a former Communist Party chief, was quoting as saying that 1 million people died, but his figure apparently excluded deaths that resulted from fighting between Red Guard factions, which most scholars believed resulted in an additional one million deaths. Most of those who died during the Cultural Revolution died from fighting among Red Guard factions and violence caused by the collapse of government and the absence of police authority.

Wang Youqin, who graduated from the Chinese Department at Peking University and who teaches at the University of Chicago, has been searching for victims of the Cultural Revolution for the last two decades. Her record is still extremely limited. [Source: Wu Renhua, Yaxue Cao, China Change, June 4, 2016 ++]

Background of the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution followed the failed Great Leap Forward and the ensuing Great Famine, when Mao and the Communist Party were on the defensive, looking for ways to rekindle revolutionary spirit. Instead of reshaping Chinese society and thought — its purported intention — the Cultural Revolution thrust much of China into social, political and economic chaos.

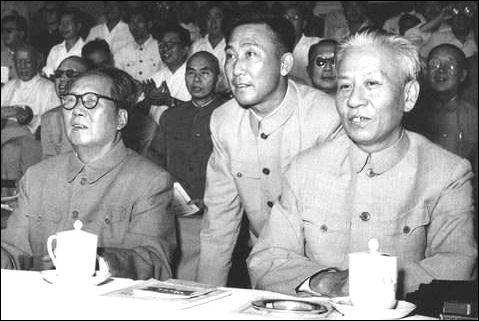

Mao at a April 1960 Politburo meeting

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The failure of the Great Leap Forward (1958-62) weakened Mao's position considerably in the Communist Party as factions began to form against him. His sense that the party was shunting him aside probably lies behind his call for a Great Revolution to Create a Proletarian Culture, or Cultural Revolution for short. But Mao also genuinely feared that China was slipping in an inegalitarian direction and he would not stand by while a new elite took over the party and subverted the revolution.[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

David McKenzie and Steven Jiang of CNN wrote: “In one sense,” the Cultural Revolution “began with the bruised ego of Mao Zedong. In the early 1960s, China's great revolutionary hero was still smarting from the catastrophic failure of the Great Leap Forward, a policy of collective farming and industry that directly and indirectly caused the deaths of millions of Chinese. Mao called on a new revolution to stamp out what he called bourgeois and counter-revolutionary influences. Conveniently, for Mao, the ensuing chaos helped shore up his personality cult and get rid of his political opponents.[Source: David McKenzie and Steven Jiang, CNN, June 5, 2014]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong had lost a substantial degree of power in the aftermath of the disastrous Great Leap Forward (1959-1961). As a result, the Communist Party pursued a number of social and economic policies, of which Mao did not approve. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: In his book on the Cultural Revolution “Dikötter, for example, convincingly evokes the paranoia that Mao and his circle felt in the early 1960s. Drawing on previously classified provincial archives, he provides evidence that after the Great Leap Famine, beginning in the late 1950s, opium was being grown again, religion was on the rise, and former officials of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party were running local governments. These were the kinds of reports that probably caused Mao to feel that the Cultural Revolution was necessary. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

Moderates Threaten Mao After the Great Leap Forward

In 1961 the political tide at home began to swing to the right, as evidenced by the ascendancy of a more moderate leadership. In an effort to stabilize the economic front, for example, the party — still under Mao's titular leadership but under the dominant influence of Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun, Peng Zhen, Bo Yibo, and others — initiated a series of corrective measures. Among these measures was the reorganization of the commune system, with the result that production brigades and teams had more say in their own administrative and economic planning. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

To gain more effective control from the center, the CCP reestablished its six regional bureaus and initiated steps aimed at tightening party discipline and encouraging the leading party cadres to develop populist-style leadership at all levels. The efforts were prompted by the party's realization that the arrogance of party and government functionaries had engendered only public apathy. On the industrial front, much emphasis was now placed on realistic and efficient planning; ideological fervor and mass movements were no longer the controlling themes of industrial management. Production authority was restored to factory managers. *

Another notable emphasis after 1961 was the party's greater interest in strengthening the defense and internal security establishment. By early 1965 the country was well on its way to recovery under the direction of the party apparatus, or, to be more specific, the Central Committee's Secretariat headed by Secretary General Deng Xiaoping. *

Mao and Liu Shaoqi

Mao and the Cultural Revolution

In the early 1960s, Mao was on the political sidelines and in semiseclusion. By 1962, however, he began an offensive to purify the party, having grown increasingly uneasy about what he believed were the creeping "capitalist" and antisocialist tendencies in the country. As a hardened veteran revolutionary who had overcome the severest adversities, Mao continued to believe that the material incentives that had been restored to the peasants and others were corrupting the masses and were counterrevolutionary. [Source: The Library of Congress]

In his book “On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet,” Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “In 1966, Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution to eliminate his enemies and reshape relations within the party. Unlike the standard Chinese Communist Party purges that took place entirely within the rarified air of the party itself, in the Cultural Revolution, the driving forces of the cleanup— Red Guards and revolutionary workers—were outside the party. Mao sought to mobilize the masses to discover and attack what he called bourgeois and capitalist elements who had insinuated themselves into the party and, in his view, were trying to subvert the revolution. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, “ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009. Goldstein is a professor in the Department of Anthropology at Case Western Reserve University]

Barbara Demick wrote in The Atlantic: “The Cultural Revolution was Mao’s last attempt at creating the utopian socialist society he’d long envisioned, although he may have been motivated less by ideology than by political survival. Mao faced internal criticism for the catastrophe that was the Great Leap Forward. He was unnerved by what had happened in the Soviet Union when Nikita Khrushchev began denouncing Joseph Stalin’s brutality after his death in 1953. China’s aging despot (Mao turned 73 the year the revolution began) couldn’t help but wonder which of his designated successors would similarly betray his legacy. [Source: Barbara Demick, The Atlantic, November 16, 2020]

“To purge suspected traitors from the upper echelons, Mao bypassed the Communist Party bureaucracy. He deputized as his warriors students as young as 14 years old, the Red Guards, with caps and baggy uniforms cinched around their skinny waists. In the summer of 1966, they were unleashed to root out counterrevolutionaries and reactionaries (“Sweep away the monsters and demons,” the People’s Daily exhorted), a mandate that amounted to a green light to torment real and imagined enemies. The Red Guards persecuted their teachers. They smashed antiques, burned books, and ransacked private homes. (Pianos and nylon stockings, Yang notes, were among the bourgeois items targeted.) Trying to rein in the overzealous youth, Mao ended up sending some 16 million teenagers and young adults out into rural areas to do hard labor. He also dispatched military units to defuse the expanding violence, but the Cultural Revolution had taken on a life of its own.

In “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng, “Mao is a demented emperor, cackling madly at his own handiwork as rival militias — each claiming to be the faithful executors of Mao’s will, all largely pawns in the Beijing power struggle — slaughter one another. “With each surge of setbacks and struggles, ordinary people were churned and pummeled in abject misery,” Yang writes, “while Mao, at a far remove, boldly proclaimed, ‘Look, the world is turning upside down!’ ” [Source: Barbara Demick, The Atlantic, November 16, 2020]

“Yet Mao’s appetite for chaos had its limits, as Yang documents in a dramatic chapter about what is known as “the Wuhan incident,” after the city in central China. In July 1967, one faction supported by the commander of the People’s Liberation Army forces in the region clashed with another backed by Cultural Revolution leaders in Beijing. It was a military insurrection that could have pushed China into a full-blown civil war. Mao made a secret trip to oversee a truce, but ended up cowering in a lakeside guesthouse as violence raged nearby. Zhou Enlai, the head of the Chinese government, arranged his evacuation on an air-force jet. “Which direction are we going?” the pilot asked Mao as he boarded the plane. “Just take off first,” a panicked Mao replied.

Four Clean-Ups (Socialist Education Movement)

The Four Cleanups — often called the Socialist Education Movement — was a purge of top-level Communist Party officials meant to remove “reactionary” elements from Chinese politics and disguised somewhat as a crackdown on corruption. Regarded by some as the true beginning of the Cultural Revolution or at least a precursor to the Cultural Revolution, it started in 1963 but really took off in 1964. One Chinese academic said: “Without quite knowing what I was doing, I joined the ranks of the persecutors.” Some have compared the sweeping anti-corruption campaign launched by Chinese president Xi Jinping in early 2013 with the Four Cleanups.

To arrest the so-called capitalist trend, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, in which the primary emphasis was on restoring ideological purity, reinfusing revolutionary fervor into the party and government bureaucracies, and intensifying class struggle. There were internal disagreements, however, not on the aim of the movement but on the methods of carrying it out. Opposition came mainly from the moderates represented by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, who were unsympathetic to Mao's policies. The Socialist Education Movement was soon paired with another Mao campaign, the theme of which was "to learn from the People's Liberation Army." Minister of National Defense Lin Biao's rise to the center of power was increasingly conspicuous. It was accompanied by his call on the PLA and the CCP to accentuate Maoist thought as the guiding principle for the Socialist Education Movement and for all revolutionary undertakings in China. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

Four Clean-Ups

“In connection with the Socialist Education Movement, a thorough reform of the school system, which had been planned earlier to coincide with the Great Leap Forward, went into effect. The reform was intended as a work-study program — a new xiafang movement — in which schooling was slated to accommodate the work schedule of communes and factories. It had the dual purpose of providing mass education less expensively than previously and of re-educating intellectuals and scholars to accept the need for their own participation in manual labor. The drafting of intellectuals for manual labor was part of the party's rectification campaign, publicized through the mass media as an effort to remove "bourgeois" influences from professional workers — particularly, their tendency to have greater regard for their own specialized fields than for the goals of the party. Official propaganda accused them of being more concerned with having "expertise" than being "red". *

Jeremy Brown, a history professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, told the New York Times: “This was the aftermath of the Great Leap Famine [considered one of the worst famines in history, with around 30 million deaths]. Mao blamed the famine on bad officials in local areas who were corrupted by remnant Nationalist forces and by landlords. He said some places didn’t do land reform well and that’s why the famine happened. It’s because of impurity in local village organization — that was Mao’s rationalization. Around this time, the early 1960s, there was a resurgence of religious practices and economic activity — things that look like capitalist buying and selling of goods. Villages are making money on the side outside the socialist economic plan.So Mao declared “we can never forget class struggle” and started the Four Cleanups. It was traumatic. Outside work teams went to villages, investigated local officials and violently punished people they considered class enemies. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, May 10, 2016]

China at the Time the Cultural Revolution Began

By mid-1965 Mao had gradually but systematically regained control of the party with the support of Lin Biao, Jiang Qing (Mao's fourth wife), and Chen Boda, a leading theoretician. In late 1965 a leading member of Mao's "Shanghai Mafia," Yao Wenyuan, wrote a thinly veiled attack on the deputy mayor of Beijing, Wu Han. In the next six months, under the guise of upholding ideological purity, Mao and his supporters purged or attacked a wide variety of public figures, including State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and other party and state leaders. By mid-1966 Mao's campaign had erupted into what came to be known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the first mass action to have emerged against the CCP apparatus itself. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

Considerable intraparty opposition to the Cultural Revolution was evident. On the one side was the Mao-Lin Biao group, supported by the PLA; on the other side was a faction led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, which had its strength in the regular party machine. Premier Zhou Enlai, while remaining personally loyal to Mao, tried to mediate or to reconcile the two factions. *

Four Clean Ups

Viewed in larger perspective, the need for domestic calm and stability was occasioned perhaps even more by pressures emanating from outside China. The Chinese were alarmed in 1966-68 by steady Soviet military buildups along their common border. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 heightened Chinese apprehensions. In March 1969 Chinese and Soviet troops clashed on Zhenbao Island (known to the Soviets as Damanskiy Island) in the disputed Wusuli Jiang (Ussuri River) border area. The tension on the border had a sobering effect on the fractious Chinese political scene and provided the regime with a new and unifying rallying call. *

There was Cultural-Revolution-like activity before the Cultural Revolution. Denise Y. Ho told the Los Angeles Review of Books: During one campaign in the years before the Cultural Revolution, officials displayed individuals’ personal possessions along with posterboards explaining why they were political enemies. Then, when the Cultural Revolution broke out, Red Guards invaded people’s homes and confiscated their belongings, putting objects on display along with posters describing their crimes. So political culture provided ordinary people with a repertoire, with an idea of how to act and how to describe their actions. This kind of evidence helps us understand where the Cultural Revolution came from, and how such propaganda was deeply powerful — sometimes producing tragic consequences.” [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook,Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016]

“Destroy the Four Olds”

During the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party encouraged young members of the Red Guard to destroy the "Eight Antis" and knockdown the "Four Olds" (thinking, habits, culture and customs). In an effort to wipe out the "Four Olds," the Red Guards destroyed ancient treasures, attacked historical buildings, humiliated college professors, professionals and doctors and even attacked people on the streets for having cuffs that were too narrow and hair that was too long. Posters read, “Suspend classes to make revolution!”

Senior leaders accused of taking "the capitalist road” were purged. Paranoid about plots against him within the Communist Party, Mao ousted moderates and liberals in the party such as Liu Shaoqui, the No. 2 leader and State President, and Peng Zhen, the mayor of Beijing. The purge later expanded to an attack on all "enemies" of the Communist Party. The Cultural Revolution coincided with the anti-Vietnam demonstrations in the United States. American Sinologists and leftists wrote glowing accounts of the Cultural Revolution, heralding it as a great revolution transformation.

Destruction of Buddhist statues

Driven by Mao’s edict to attack the “four olds,” gangs of Red Guards smashed up temples, destroyed artwork, and demolished libraries and cemeteries. The Communist Party cheered on the destruction, with the People’s Daily publishing a June 1 editorial exhorting cadres to “sweep away all monsters and demons!” A Red Guard leader who led raids on temples and other cultural treasures told the Christian Science Monitor: “Chairman Mao called for us to ‘Destroy the Four Olds’… and whatever Chairman Mao said, we did it right away.” [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

Zehao Zhou wrote in USA Today: “Waves of violence swept across the country: Foreign embassies were sacked. Political untouchables were summarily deported from the city or even buried alive. Suicides became widespread. Among the most atrocious events that occurred during the tumultuous summer of 1966 was the “Destroy the Four Olds Campaign.” Anything that expressed old ideas, old habits, old customs and old culture was subject to the wrath of the Red Guards. [Source: Zehao Zhou, USA Today Network, May 14, 2016 ^*^]

“In just a few weeks, the material representation of 5,000 years of Chinese civilization was summarily destroyed or irrevocably damaged — the equivalent of the eradication of all material symbols of the Greek, Roman and Judeo-Christian traditions. The numbers are mind-boggling: Almost 90 percent of Tibet’s monasteries and temples were razed and roughly 74 percent of the historic sites in the birthplace of Confucius, China’s Jerusalem, were obliterated. ^*^

“In my own Shanghai neighborhood, what I will always remember is when a pack of Red Guards attacked our community church, brought out all of its Bibles into the middle of the street and set them on fire. That horrific moment — seeing the sky darkened with the floating ashes of burned Bibles — remains seared in my memory even now.” ^*^

Carrying Out the “Destroy the Four Olds” See Separate Article RED GUARD VIOLENCE AND DESTRUCTION factsanddetails.com

Destruction of Art, Temples and Embassies during the Cultural Revolution

In their attempt to wipe out China's past and create a new society, Red Guards destroyed any precious painting, vase, pottery, calligraphy, embroidery, statue, book or works of art they could their hands on. Owners destroyed their own stuff to avoid getting caught with it. One man told the Washington Post that he watched his mother destroy a valuable old painting. "She was afraid the Red Guard would come and find it, and then they would kill us," he said.

The Red Guard and supporters of the Cultural Revolution also destroyed temples and historical buildings. Between 1970 and 1974 an army unit stationed at Gubeikou tore down two miles of the Great Wall and used the stone blocks to construct army barracks. In Tibet the Red Guard turned thousand-year-old monasteries into factories and pigsties. At the Shanghai Art Museum, curators slept in the museum to fend off Red Guard attacks.

A Mao portrait painter and loyal communist was exiled to a framing factory. His crime: painting portraits of Mao at a slight tilt so that only one ear showed, implying that Great Helmsman listened only to a select few not every one. “How many ears I painted was not up to me. It was decided by the central government,” the artists told the Los Angeles Times.

In August 1967, during an anti-foreigner phase of the Cultural Revolution, the British embassy was gutted and burned. All 23 people who were inside the embassy at the time felt lucky to escape with their lives. A British diplomat later told the Times of London that at 10:30am a flare lit the sky and a crowd began climbing over the walls. The occupants of the embassy withdrew into a barred room while the crowd shouted "kill, kill, kill” and set the building on fire. The occupants had hoped to sit out the attack but the room grew hotter and hotter and they fled the building by a concealed concrete door. The diplomat told the Times: “As we went out we fell into the arms of the mob. Hands went up women’s skirts. The men has their testicles screwed.” Somehow they managed to make it out of the compound, where they were rescued by PLA soldiers and taken to their diplomatic housing." Chinese were also harangued for their associations with foreigners. People with Canadian-made alarm clocks were accused of worshiping foreign enemies and forced to endure "struggle sessions."

Crackdown on Religion during the Cultural Revolution

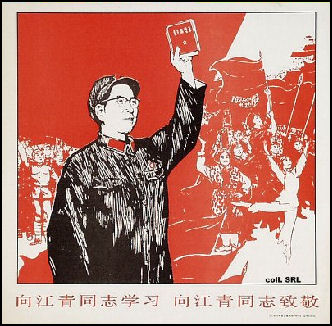

JIang Qing poster

Religion was effectively outlawed during the Cultural Revolution and many temples were destroyed and religious objects were melted down for their gold. Red Guards did not discriminate against particular religions, they were against them all. They ripped crosses from church steeples, forced Catholic priests into labor camps, tortured Buddhist monks in Tibet and turned Muslim schools into pig slaughterhouses. Taoists, Buddhists and Confucians were singled out as vestiges of the Old China that needed to be changed.

One Chinese man told Theroux about an effort by the Red Guard to tear down a cross from the largest church in Qindao: "The Red Guards held a meeting, and then they passed a motion to destroy the crosses. They marched to the church and climbed up to the roof. They pulled up bamboos and tied them into a scaffold. It took a few days “naturally they worked at night and they sang the Mao songs. When the crowd gathered they put up ladders and they climbed up and threw a rope around the Christian crosses and they pulled them down. It was very exciting!"

During the Cultural Revolution, the Confucius Temple in Qufu, Confucius’s hometown, the temple was sacked as Confucius was denounced as a class enemy. An enormous statue of Confucius was dragged through the streets and smashed with sledge hammers. Corpses were dug up from their graves at the Kong family's cemetery and hung from trees. More than 6,000 artifacts were smashed or burned.

In his book on the Cultural Revolution, Dikötter “uses archives to show how thousands of people engaged in producing statues, incense, and other objects used in religious worship were thrown out of work when religion was effectively banned.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

Jiang Qing, Mao and the Gang of Four

Jiang Qing — a former Shanghai movie actress, Gang of Four member and Chairman Mao's forth wife —is believed to have been one of the masterminds of the Cultural Revolution. According to some scholars the whole ordeal grew out of an attempt to extrapolate her radical ideas about the arts to society as a whole and became an experiment that went out of control.

Others disagree and say Mao was the mastermind. One bodyguard said: “Jiang Qing could only make suggestions not decisions.” Some believe that she made a kind of deal with Mao in that she would look the other towards his philandering’she once caught him in bed with one of her nurses and for a while was only allowed to speak to him through his mistress if he gave her radical leftist political ideas support.

Mao is now widely regarded not only as the inspiration for the Cultural revolution but was also the instigator of it and micro-manager of many of its events. Mao felt that revolutionary spirit had disappeared and the government had become ruled by a new class of mandarins — engineers, scientists, scholars and factory managers —and these people were a threat to his power and something had to be done to undermine them.

The Cultural Revolution was blamed almost entirely on the Gang of Four, a group of Communist leaders, with their power base in Shanghai, made up of Mao's wife Jiang Qing and her three allies — Yao Wenyuan, Zhang Chunqiao and Wang Hongwen. When the Chinese refer to the Gang of Four today they sometimes hold up five fingers — the fifth being a reference to Mao himself.

The Gang of Four directed the purge against moderate party officials and intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution. Jiang was leader. Yao, dubbed killer with a pen, was the group’s propagandist. On Jiang’s order Yao wrote the review condemning the popular Beijing play that triggered the Cultural Revolution. A diary entry revealed during his trial read: “Why can’t we shoot a few counterrevolutionary elements? Afer all, dictatorship is not like embroidering flowers.”

Qi Benyu: Cultural Revolution Propagandist

Young Jiang Qing and Mao

Qi Benyu (1931-2016) was a Communist Party theorist and propagandist who played a significant role in the Cultural Revolution. Cary Huang wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Qi was the last member of the ultra-left Cultural Revolution Group (CRG), which had superseded the party’s top decision-making Politburo and Secretariat to emerge as the de facto top power organ of the country at the height of the political turmoil between 1966 and 1976. Qi was a Shandong resident born in Shanghai. [Source: Cary Huang, South China Morning Post, April 21, 2016 ++]

“Once the late leader Mao Zedong’s right-hand man for propaganda, Qi is said to have played a role that led to the purge of President Liu Shaoqi. Until recently, Qi continued to air his ultra-left views, with radical calls to relaunch the Cultural Revolution in the country. Qi’s political career was associated with Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife. He was made a staff member at Mao’s personal office in 1950 after graduating from the Youth League school. The office was led by Jiang. Qi had been elevated to become the acting director of the general office of the party’s Central Committee and the deputy editor of Red Flag, the ruling party’s theoretical journal and a key source of Maoist ideological inspiration and guidance during the Cultural Revolution. It was replaced by a magazine called Qiushi, or Seeking Truth, in 1988. Lessons from 1966: why we should never forget the disastrous consequences of the Cultural Revolution. ++

“Qi and Yao Wenyuan, a member of the notorious “Gang of Four” led by Jiang, played the crucial role in a campaign to denounce a historic Beijing opera called Hai Rui Dismissed from Office, which was seen as a prelude to the launch of the Cultural Revolution. As a secretary at Mao’s office and a closeaide of Jiang, Qi had also played a key role in the draft of the so-called “May 16 Notification”, which, formalised by “an expanded Politburo” meeting, announced the establishment of the CRG and also declared the launch of the Cultural Revolution by announcing the overthrow of a group of moderates, including Beijing party boss Peng Zhen and police chief Luo Ruiqing.” ++

Unpublicized Side of the Cultural Revolution

Many cities were torn apart by the Cultural Revolution but much of the countryside was unaffected and the economy, despite a slowdown k in 1968, suffered little. According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: “Economically, the emphasis in the 1960s and early 1970s was on agriculture. After the Cultural Revolution, economic programs were initiated featuring the establishment of many small factories in the countryside and stressing local self-sufficiency. Both industrial and agricultural production records were set in 1970, and, despite serious droughts in some areas in 1972, output continued to increase steadily. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Jeremy Brown, a history professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, told the New York Times: The heart of the Cultural Revolution “was really a three-year period. The Red Guards were part of it, but there was more violence in 1968-69, when Mao sent the army and tried to restore order by setting up Revolutionary Committees. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, May 10, 2016 ^|^]

“We don’t hear too much about the “rebels.” They were workers in factories, not Red Guards, and they got a seat at the table when the Revolutionary Committees were set up in 1968. They ran factories and many workplaces along with the army. They were the ones who got scapegoated at the end of the Cultural Revolution. They’re not super literate or well-connected enough to get their stories out, and their stories are embarrassing to the officials who used them and survived and did well after the Cultural Revolution. They’re called “Gang of Four elements.” We don’t know much about them at all. ^|^

“Policies didn’t take effect simultaneously across China. Things were happening at a different timeline in villages and factories. People also didn’t understand the policies — they were confusing and contradictory — and did what made sense to them. They were reading the newspaper or listening to the broadcast and figuring out what the policy was going to be, but it didn’t translate into what happened in a village.” ^|^

We often have images of mass rallies, but many people opted out. Don’t forget, most people didn’t go. It’s interesting to think of that — most did not participate. And the economy kept going. There were no widespread famines. People still went to school in unprecedented numbers. When you look at the Mao cult and the way that people were performing rituals to the “great leader” — doing the loyalty dance, for example — they seem like absurd rituals. But it was a limited period of time. There were a few cities where the Mao cult was intense. But if you look at the whole period from the mid-60s to mid-70s, you have all sorts of people detaching themselves from politics and focusing on their work. You have a Mao picture in the workplace, and campaigns, but it’s background noise for many people. That political narrative was not first on their minds when they went about their lives. ^|^

“Sometimes you can’t get around it, like the chapter on the young fellow in Tianjin trying to avoid being sent down to a village as part of a massive social engineering project. It’s based on excerpts from the young man’s diary and reads like any teenager’s diary. He’s worried about what people think of him, what’s next in his life.” ^|^

Could the Cultural Revolution Have Been Stopped

"There were at least two points where (Party officials) could have done something," Dikotter told CNN. Following the Great Leap Forward, "Mao's star is very much at its lowest, at that point they could have hemmed him in, but the Chairman manages to very astutely talk his way out of that predicament.” By taking partial blame for the disaster, Mao forced other high-ranking officials to admit their own complicity, undermining their authority and strengthening his position. [Source: James Griffiths, CNN, May 13, 2016 /^]

"The second point is probably in February 1967 when several veteran marshals openly rebel against the Cultural Revolution group presided over by Madame Mao," Dikotter says. "Mao realizes that if these veteran marshals push their criticisms through, it would have dire consequences and he might end up being at the losing end.” But Mao, the "master of corridor politics" was able to keep Premier Zhou Enlai and other key officials on side, and eventually the generals were denounced and purged. /^\

“Ultimately, any attempt to stop the Cultural Revolution was hamstrung by the same reason today's China has been unable to properly reckon with its history: the primacy of Mao. "When Kruschev started de-Stalinization he knew full well you can drag Stalin's body out of the mausoleum because there is another body there, Lenin's," says Dikotter. "In the case of China this would be impossible, the entire history of the Chinese Communist Party revolves around the personality of Mao... which is why the Party will never, ever promote a critical examination of its own history.”“ /^\

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; photos, Ohio State University; Wiki Commons; History in Pictures blog; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021