DAILY LIFE DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

Cultural Revolution Wedding

During the Cultural Revolution people in Beijing burned their own books and smashed heirlooms. People were so afraid that the Red Guards would find antiques in their home, they would toss them into the river at night so no one would see. Records from 1972, taken at a grade school outside Beijing, show that math students were made to sing two revolutionary songs and study and discuss six Mao quotations for 25 minutes of each class. The remaining few minutes were spent doing math. [Source: Xiyun Yang and Michael Wines, New York Times, January 25, 2010 +++]

In 1967, a report urged forming special groups at the provincial and city levels to use every conceivable means to guarantee production each year of 13,000 tons of specially formulated red plastic required for the covers of Mao’s Little Red Book of quotations. The Conference on the Situation of the Special Plastic Used by the Works of Chairman Mao proclaimed that producing the plastic was our glorious political responsibility. +++

Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times: “Often the biggest event was when a criminal was executed, when the whole town would become as lively as festival time. The writer Yu Hua told the New York Times he remembers the executions as the most thrilling scenes of his childhood, seeing the criminal kneeling on the ground, a soldier aiming a rifle at the back of his head and firing.... Books were hard to come by during the Cultural Revolution, or they would circulate in mutilated form, The writer Yu Hua said he read the middle of a torn copy of a novel by Guy de Maupassant (I remember it had a lot of sex, he said) without knowing its title or author. His formative reading experience was provided by the big character posters of the Cultural Revolution, in which people denounced their neighbors with violent inventiveness. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Howard W. French wrote in The Nation: “The writer Liao Yiwu was born in Sichuan Province in 1958. At the outset of the Cultural Revolution, in 1966, his late father, a small landlord, was jailed as a “class enemy.” In fact, the family had been targeted for persecution since 1959 when his mother, a music teacher, was fired from her primary school job for “bourgeois thinking.” After being caught trading ration coupons for food, Liao's mother ran away with her son and a younger sister to Chengdu, Sichuan's big provincial capital, where they lived a precarious life without a residence permit. Liao left home two years later, at age 10, hoping to find his father and eventually making a living through a succession of small hard-knock jobs, hauling rocks or rolling cigarettes. In the early 1970s, his father was released from jail and allowed to teach at a rural middle school. Schools had been closed throughout the country amid the political chaos, and Liao, already in his early teens, went to primary school in the same town where his father worked.” [Source:Howard W. French, The Nation, August 4, 2008]

The selling pigeons at an impromptu street market was seen as an obstacle to the triumph of socialism. According to a report filed by an official in 1966, crowds of 500 or more, corrupted by dreams of profit, were gathering every Sunday on a street in the city’s embassy district to ply a shameful trade. They were learning how to do business and raise money, the city official wrote. This is seriously harmful to the healthy growth of the successors of the proletariat revolution, the official said, and a waste of bird feed, too.

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org ; Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; REVOLUTIONARY ENTHUSIASM, MANGOES AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: DEATH TOLL, FIGHTING AND MASS KILLING factsanddetails.com; BACK TO THE COUNTRYSIDE MOVEMENT OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; WINDING DOWN AND END OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND TRIAL OF THE GANG OF FOUR factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Memoirs and Novels Set in the Cultural Revolution “Blood Red Sunset: A Memoir of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ma Bo and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; "Wild Swans” by Jung Chang, an international bestseller Amazon.com; “Life and “Death in Shanghai” by Nien Chang Amazon.com; “Colors of the Mountain” by Da Chen(Random House, 2000), a coming-of-age set in the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com; “The Lily Theater: A Novel of Modern China” by Lulu Wang is an entertaining and interesting depiction of the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com Sent Down Youth “Across the Great Divide: The Sent-down Youth Movement in Mao's China, 1968–1980" by Emily Honig and Xiaojian Zhao Amazon.com; “Collective Memories of 48 Sent-down Youths in Liaoxi-shenyang Once the Paddy Rice Production "Expert" the Sent-down Youths Point of Yuxin Village” by Zhang Ling Amazon.com; “China's Sent-Down Generation: Public Administration and the Legacies of Mao's Rustication Program” by Helena K. Rene Amazon.com; “China's Sent-down Youth” by Xuepei Kang Amazon.com About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com

Finding Solace with Family During the Cultural Revolution

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian: To use an analogy current at the time, each of us was a little drop of water, gathered into the great flood of socialism. But it wasn’t so easy to be that drop of water. In my town, there was a Cultural Revolution activist who would almost every day be at the forefront of some demonstration or other, often being first to raise his fist and shout “Down with Liu Shaoqi!” (Liu, nominally the head of state, had just been purged.) One day, however, he inadvertently misspoke, shouting “Down with Mao Zedong!” instead. Within seconds he had been thrown to the ground by the “revolutionary masses”, and thus he began a wretched phase in life, denounced and beaten at every turn. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018. Yu Hua is a famous writer in China, considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize. He is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant”, “To Live” and “Brothers.”]

“In that era, the individual could find space only in the context of family life — any independent leanings could only be expressed at home. That is why family values were so important to Chinese people then, and why marital infidelity was seen as so intolerable. If you were caught having an extramarital affair, the social morality of the day meant that you would be subjected to all kinds of humiliation: you might be paraded through the streets with half your hair shaved off or packed off to prison.

“During the Cultural Revolution, there were certainly cases of husbands and wives denouncing each other and fathers and sons falling out, but these were not typical — the vast majority of families enjoyed unprecedented solidarity. A friend of mine told me her father had been a professor at the start of the Cultural Revolution, while her mother was a housewife. Her father, born to a landlord’s family, became the target of attacks, but her mother, from a humbler background, was placed among the revolutionary ranks. Pressed by the radicals to divorce her father, her mother outright refused — and not only that: every time her father was hauled off to a denunciation session, she would make a point of sitting in the front row and, if she saw someone beating her husband, she would rush over and start hitting back. Such brawls might leave her bruised and bleeding, but she would sit back down proudly in the front row, and the radicals lost their nerve and gave up beating her husband. After the Cultural Revolution ended, my friend’s father told her, with tears in his eyes, that had it not been for her mother he might well have taken his own life. There are many such stories.

Surviving and Standing Up to the Cultural Revolution

Zehao Zhou, who was an 11-year-old in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution, wrote in USA Today: “Red Guards, mostly brainwashed teenage hooligans, stormed into any neighborhood they pleased, assaulted anyone they wanted, and tortured their victims to death with impunity — all in the name of revolution. "Be violent!" Mao told the impressionable students that he had just christened as Red Guards. Legions of them then embarked on a rampage across the country to carry this new gospel of destruction to every corner of China. [Source: Zehao Zhou, USA Today Network, May 14, 2016; Zehao Zhou is now an assistant professor at York College of Pennsylvania ^*^]

“No real resistance ensued. The state was Mao and Mao was the state. I remember the Chinese version of Kristallnacht in summer 1966 when waves of Red Guards from different factions repeatedly stormed my bourgeois neighborhood in the former French Concession of Shanghai over a period of weeks, terrorizing the innocent, ransacking homes and parading victims through the streets for the purpose of public humiliation. ^*^

“Screaming, shouting, yelling and cries for help rang out all around me. Nearly every household was subjected to such abuse. Chaos was the order of the day. When word came that the Red Guards were on their way to raid our neighborhood, my mother hurried to destroy any “incriminating evidence” that could be used against our family. After closing the curtains, she started to burn books, notebooks and the entire collection of family photos. I saw my mother gingerly putting one photo after another into the flames. I never had seen most of them before. The only time I got to see what my parents looked like at their wedding or how my father looked in uniform was in those fleeting moments before each photo started to curl and blacken in the flames.”^*^

Chen Qigang, a composer who now lives in France, was a student at a middle school in Beijing when the movement began. He spent three years in a re-education labor camp outside the city. He told the New York Times: I have always been a very direct speaker. When the Cultural Revolution was starting, I spoke out about what I was seeing. The day after I said something, a big-character poster appeared on campus overnight: “Save the reactionary speechmaker Chen Qigang.” I was so young. I didn’t understand what was going on. Yesterday we were all classmates. How come today all of my classmates are my enemies? Everyone started to ignore me. I didn’t understand. How could people be like this? Even my older sister, who was also at my school, came to find me and asked, “What’s wrong with you?” You saw in one night who your real friends were. The next day I only had two friends left. One of them is now my wife.[Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“At the time, no one really knew who was for or against the revolution. It was completely out of control. The students brought elderly people into the school and beat them. They beat their teachers and principals. There was nothing in the way of law. There was a student who was two or three years older than me. He beat two elderly people to death with his bare hands. No one has talked about this even until this day. We all know who did it but that’s the way it is. No one has ever looked into it. These occurrences were too common.” ~~

Artist Xu Weixin Recalls the Cultural Revolution

Local dance troupe

Xu Weixin is an artist who specializes in creating immense black-and-white Cultural Revolution portraits. Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Each standing 2.5m tall, they are both personal and powerful, demanding attention. The monochrome oils are in stark contrast to the garish colours of 60s propaganda. Some of Xu's subjects were victims, some perpetrators. Many were both. Mao is there, as is his infamous wife Jiang Qing; so are unknown scholars and Red Guards. It has taken the artist five years to complete this series of just over 100 paintings. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

No portrait is more important to Xu Weixin than his first. It was 1966; the artist was eight; and he had learned, to his shock, that his kindly young teacher was the daughter of a landlord — an enemy of the people. Outraged, he drew a hideous caricature and pinned it to the blackboard. When Miss Liu entered the classroom, "She turned pale but didn't say a word," he said. She had good reason to be frightened. The Cultural Revolution was at its height. Xu says. "I feel guilty [about my teacher]; but it also helps me to understand. People who were close to you — who were friendly and kind — could suddenly turn upon you."

"It's very, very vivid," Xu says. "I remember all the demonstrations and public denunciations; people breaking pictures and smashing Buddhas. At the beginning, people were using bricks or wooden rods and metal bars to hurt people. We could hear gunshots at night and people were beaten to death."

As a child he, too, believed the Cultural Revolution was "a great thing, a right thing, and something we must do". "Most people think the Cultural Revolution was the Gang of Four's fault, but actually everyone should be responsible." That includes the eight-year-old who scrawled his teacher's picture. That Miss Liu survived the decade largely unscathed is some comfort, Xu says, but, "Of course, I was responsible. It's only a question of how great or small my responsibility was."

Cultural Revolution from the Perspective of a Six-Year-Old

Young Red Guards

Zha Jianying, the author of several books about contemporary Chinese culture Zha grew up in Beijing and now splits her time there and in New York. She told the New York Times: “I was 6. In my first year of kindergarten, my teachers began to put up so-called Big Character Posters and we as little kids were asked to help carry these buckets of paste, which was used as glue to put up these posters. My father was a research fellow and we lived in the apartment housing of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. [Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“One night these rebels – Red Guards – burst into the apartment, turning everything inside out. My little brother was so scared – he was 4 or 5. I remember one of the leaders, taking me aside and say: “Your parents are bad people. They are the class enemy. You and your brother should make a clear line from them.” My parents were taken downstairs and there was this typical rally: slogans, speeches, shouting. After the rebels left, my brother and I were hiding in the bedroom because we were also afraid of our parents now: Are they the class enemy? Another night, in the building next to us there was an old scholar, he was groaning as he was being beaten. And then the next morning he was dead. They just carried him away. ~~

“In early 1981, when I was at Peking University, my mother came home, and said she had been lining up for fish at the market. It was a long line, and she realized the man standing in front of her looked familiar. She checked him out, and sure it was the leader of the Red Guards who had come to our house. “Do you remember me?” she said loudly. Then, she started telling everyone on the line: “YOU are one of the rebels who came to my house to ransack it.” In the period after the Red Guards burst into our apartment, my mother had been interrogated daily and forced to do different kinds of labor because she was considered a black guard. So in front of this man, she recounted the whole thing in public with him there. She may have cursed him, saying: “Shame on you.” Finally the man just left.” ~~

Cooperating with the Forces of the Cultural Revolution

In a review of “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin, Zha Jianying wrote in the New York Review of Books: “A noteworthy feature of The Cowshed is its entangled theme of guilt and shame. In memoirs about Maoist persecutions, authors typically portray themselves as either hapless, innocent victims or, occasionally, defiant resisters. The picture is murkier in Ji’s recollection. He writes about Chinese intellectuals’ eager cooperation in ideological campaigns and how, under pressure, they frequently turned on one another. [Source: Zha Jianying, New York Review of Books, January 26, 2016 *]

He mocks his own “aptitude in crowd behavior” and admits that, until his own downfall, he had also persecuted others: ‘Since we had been directed to oppose the rightists, we did. After more than a decade of continuous political struggle, the intellectuals knew the drill. We all took turns persecuting each other.This went on until the Socialist Education Movement, which, in my view, was a precursor to the Cultural Revolution.’ And what was his involvement in the Socialist Education Movement? “Without quite knowing what I was doing, I joined the ranks of the persecutors.” *\

“To Ji, this is a forgivable sin because if he and many other Chinese intellectuals have been guilty of persecuting one another, it was largely because the intellectuals as a class had been compelled to feel deeply guilty and shameful about themselves. Ji described how this was achieved through the fierce criticism and self-criticism sessions, a unique feature of the Maoist thought-reform campaigns. Ji’s own ideological conversion was accomplished through such a ritual. *\

“Impressed by the Communist victory and early achievements, he blamed himself fervently for not being sufficiently patriotic and selfless: he was selfish to pursue his own academic studies in Germany while the Communists were fighting the Japanese invaders; he was wrong to avoid politics and to view all politics as a tainted game, because the Communist politics was genuinely idealistic and noble. Only after beating himself up about all his sins did he manage to pass the collective review and gain acceptance as a member of the “people.” *\

Mao loyalty dance

“Ji describes the overwhelming sense of guilt as “almost Christian,” which led to a feeling of shame and induced a powerful urge to conform and to worship the new God—the Communist Party and its Great Leader. Afterward, like a sinner given a chance to prove his worthiness, he eagerly abandoned all his previous skepticism—the trademark of a critical faculty—and became a true believer. He embraced the new cult of personality, joining others to shout at the top of his voice “Long Live Chairman Mao!” Through this process, millions of Chinese intellectuals cast off their individuality. For Ji, the feeling of guilt became so deeply engrained that, even after he was locked up in the cowshed, he racked his brain for his own faults rather than questioning the Party or the system. *\

“Ji was obviously not a shrewd political animal or a deep thinker. Admitting that his eyes were finally opened only after the Cultural Revolution ended, he refrained from analyzing the larger political picture or interpreting the motives of those who launched the chaos. But he clearly felt that the country on the whole had failed to learn a real lesson from what happened.” *\

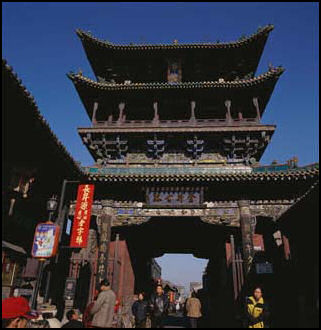

How Pingyao Survived the Cultural Revolution

Pingyao — the beautiful, ancient Chinese town described by Lonely Planet as “China’s best-preserved ancient walled town.” survived the Cultural Revolution through an unexpected stewardship of strategic Red Guard leader. Leavenworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: “In recent years, first-hand accounts have shed some light on this period in Pingyao... and the story starts with Suo Fenqi, who in 1966 was an 18-year-old local leader of the Red Guards, the revolution’s shock troops. Fit and handsome, Mr. Suo was born into a farm family that sang songs praising Chairman Mao. His parents had both joined the Communist Party years before the 1949 founding of the People’s Republic of China. “I had a good red family background,” Suo says. “That’s why I was picked to be a Red Guard leader.” [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

“Pingyao at that time was a dusty and isolated place, 440 miles southwest of Beijing. Its ancient architecture and courtyard homes were still intact, but its neighborhoods were in transition. One of Suo’s duties was to go door-to-door with other Red Guards, seizing hidden gold and other booty, and driving intellectuals and the wealthy from their homes. In and around Pingyao, there were two Red Guard factions: one loosely allied with the military, another allied with Chen Yongui, the Communist party secretary from nearby Dazhai. Mr. Chen was a close ally of Mao, but in 1967 he was being hounded by his rivals. He set up his headquarters in Pingyao’s Chenghuang Temple, which dates back to the Northern Song Dynasty of the 1200s. Suo joined him there. |~|

“Chen’s faction was badly outgunned by its adversaries, according to Suo, and soon faced a choice: fight or flee. Some advocated retreating to Xian, an ancient city to the South. Suo says he argued for staying and defending Pingyao by fortifying the walls. His argument won the day. Even before the Cultural Revolution, Pingyao’s 39-foot-high walls – topped by six dozen watch towers – had fallen into disrepair. At night, peasant farmers would burrow into the walls, hauling away bricks for their houses and pig pens. Suo organized 300 of his men to take back the pilfered building materials and repair the walls. Another 300 people were charged with guarding them and watching out for attacks, he says. |~|

“By early 1969 the two factions, armed with rifles, machine guns, mortars and other weaponry, were girding for a bloody assault. “Personally I did not want to fight, but I had no choice,” recalled Suo. “If I had tried to go home (outside the town walls) someone from the other faction would probably have caught me and killed me.” At the last moment, Pingyao was granted a reprieve. The Red Army disarmed the Red Guard factions, as it had done elsewhere in China as Mao sought to restore order in the country. The ancient walls of Pingyao had endured. But it had had nothing to do with historical preservation, says Suo. “The real reason Pingyao’s walls survived was to protect our faction.” “ |~|

Preservationist Helps Save Pingyao in the Cultural Revolution

Pingyao Stuart Leavenworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: “During the early years of the Cultural Revolution a quiet preservationist named Li Youhua embedded himself with Suo and his allies. A skilled artist and calligrapher, Mr. Li lived with Chen and Suo in the Chenghuang Temple, but he kept his head down because of his family background; his grandfather had been accused of being a collaborationist during the Japanese occupation. Li died in 1999, but he left behind a trove of letters, drawings, and photographs of his restoration work in Pingyao and other cities. In 2002, his son Li Shujie assembled these papers into a pair of books, which tell the story of a relentless preservationist. According to his son, Li was appalled by the Red Guards’ destruction of antiquities, but he could not openly protest. “It was too dangerous,” says Mr. Li. Carefully and quietly though, his father saved what he could. [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

“Outside Pingyao, Red Guards had started smashing the Shuanglin Temple, an old Buddhist temple that had been rebuilt in 1571. According to his son, Li snuck into the temple and brought out a colorful sculpture from the Hall of One Thousand Buddhas. Later he returned it to the temple. Local peasants also rallied to save some of Shuanglin’s sculptures and artwork, says Suo. “Unlike the intellectuals,” he says, “the farmers were not afraid of the Red Guards.” |~|

“When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, Li Youhua joined what later became Pingyao’s cultural heritage department, where he continued to fight to preserve remnants of China’s past. Pingyao’s biggest employer was a tractor factory near the north wall of the city. A flood damaged the factory’s dormitory in 1977, and officials proposed rebuilding it on top of the wall. Li protested, and then quietly organized political opposition to the project, says Li Shujie. Eventually the provincial Communist party secretary intervened, saving the north wall from a misguided alteration.” |~|

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; photos: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org, Ohio State University; Wiki Commons; History in Pictures blog

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021