"GO TO WORK IN THE COUNTRYSIDE AND MOUNTAINOUS AREAS!"

In December 1968, the Cultural Revolution entered a new phase when Mao called on urban-educated youth to go to the countryside to "learn from poor and middle-level peasants." The initiatives was partly viewed as a means of diffusing the Red Guards who were sometimes rounded up with deadly force. Those that participated on the movement as a whole are today generally referred to Sent-Down Youth.

During the Cultural Revolution, about 30 million educated youths were sent to rural areas to work in the countryside and learn from the peasantry. Mao believed that this would ultimately create a new society where there was no gap between urban and rural, laborers and intellectuals. Under the slogan: “Go to work in the countryside and mountainous areas!” Mao ordered educated youths (high school graduates) in cities to be sent to the countryside to “receive re-education from poor and low middle-class peasants”. From then on until the end of the Cultural Revolution, each year millions of students said good-bye to their families to go to work in the countryside. Many current Chinese officials in their mid- or late-50s, including Vice President Xi Jinping and Vice Premier Wang Qishan, belong to this “sent-down” generation. [Source: Sun Wukong and Wu Zhong, Asia Times, March 3, 2009]

“Going to work in the countryside and mountain areas” was compulsory for every urban student. Over 16 million urban students were carted off to remote parts of China such the Yunnan Province to be re-educated. They were organized into companies and regiments, and lived on farms, ate in communal cafeterias and performed tasks like digging ditches, cutting bamboo and planting rice. The idea behind the campaign was that manual labor could re-install socialist values. One Cultural Revolution-era slogan went: “Our aspirations to settle in the countryside are unwavering.” Urban youth converted cotton fields to rice paddies with their bare hands. The acclaimed Chinese director Chen Kaige was sent away to the Yunnan Province where he spent four years cutting bamboo. He was 14 when the Cultural Revolution began. His father, a former member of Chiang Kai-shek's nationalist party, was taken away to a re-education camp.

In the countryside people lived off corn porridge and sliced radishes, and boiled mutton. They shoveled cow and sang revolutionary songs and lived a life they described a of "eating bitterness." Self-criticism was a common practice for acts that were considered wrong but were not necessarily crimes. Participants typically confessed, apologized and said they would not do it again. People were tortured and deprived of sleep until they wrote fake confessions implicating their friends.

Intellectuals and other enemies of the Cultural Revolution were also sent to the countryside as punishment. One man told Theroux, "My family was sent for reeducation, to a remote place to plant rice. My father had been an English teacher in a middle school. The family worked on the land, learning from peasants, for six years. ...For the first year we had no house. We lived in a sort of barn — a place where grain was stored. We had no crops. We ate the local leaves and roots, living like animals."

There were also broader, national objectives of the program. According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: "More than 60 million students, officials, peasant migrants, and unemployed were sent "down to the countryside" in a gigantic rustication movement. The goals of this program were to relocate industries and population away from vulnerable coastal areas, to provide human resources for agricultural production, to reclaim land in remote areas, to settle borderlands for economic and defense reasons, and, as has been the policy since the 1940s, to increase the proportion of Han Chinese in ethnic minority areas. Another purpose of this migration policy was to relieve urban shortages of food, housing, and services, and to reduce future urban population growth by removing large numbers of those 16–30 years of age. However, most relocated youths eventually returned to the cities. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com; REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; SURVIVING AND LIVING THROUGH THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; WINDING DOWN AND END OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND TRIAL OF THE GANG OF FOUR factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Sent Down Youth “Across the Great Divide: The Sent-down Youth Movement in Mao's China, 1968–1980" by Emily Honig and Xiaojian Zhao Amazon.com; “Collective Memories of 48 Sent-down Youths in Liaoxi-shenyang Once the Paddy Rice Production "Expert" the Sent-down Youths Point of Yuxin Village” by Zhang Ling Amazon.com; “China's Sent-Down Generation: Public Administration and the Legacies of Mao's Rustication Program” by Helena K. Rene Amazon.com; “China's Sent-down Youth” by Xuepei Kang Amazon.com; Memoirs and Novels Set in the Cultural Revolution “Blood Red Sunset: A Memoir of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ma Bo and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; "Wild Swans” by Jung Chang, an international bestseller Amazon.com; “Life and “Death in Shanghai” by Nien Chang Amazon.com; “Colors of the Mountain” by Da Chen(Random House, 2000), a coming-of-age set in the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com; “The Lily Theater: A Novel of Modern China” by Lulu Wang is an entertaining and interesting depiction of the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com

Cultural Revolution Gets Out of Hand and Efforts to Reign in the Violence

Mao cheered on the Red Guards in hopes they would quash potential rivals and re-energize socialism. But the unleashed mobs got out of control. In many parts of China, rival groups of Red Guards clashed with one another. Sergey Radchenko wrote in China File: “It did not take long before Mao’s delight turned to disillusionment. In 1969 he called on the army to restore a semblance of order, appointing Minister of Defense Lin Biao as his heir-apparent. But Lin Biao, too, disappointed Mao. In 1971 he fled north after the uncovering of his son’s plot to assassinate Mao. Lin never made it: his plane crashed in Mongolia. Aware of unleashing a chaos that he was no longer able to control, and fearful of Soviet invasion, Mao turned to the United States.” [Source: Sergey Radchenko, China File, Foreign Policy, September 8, 2016 ||*||]

Yiching Wu told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “The disorder caused by mass insurgencies from below and paralyzing power conflicts at the top created a crisis. The nation was on the brink of anarchy. For example, some young radicals, invoking the historical example of the Paris Commune, claimed that China’s “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” would have to be toppled in order to establish a society in which the people can self-govern. Mao decided the crisis would have to be resolved. Quashing the restless rebels, the revolution cannibalized its own children and exhausted its once explosive energy. The demobilization of freewheeling mass politics in the late 1960s helped to restore the authority of the party-state, but also became the starting point for a series of crisis-coping maneuvers which eventually led to the historic changes in Chinese society and economy a decade later. [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook, Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016]

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “Rising violence later compelled party leaders to send in the People's Liberation Army to reassert control as many government functions were suspended and long-standing party leaders sent to work in farms and factories or detained in makeshift jails. To put a stop to the violence and chaos, millions of students were dispatched to the countryside to live and work with the peasantry, among them current President Xi Jinping, who lived in a cave dwelling for several years in his family's ancestral province of Sha'anxi. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 16, 2016 =]

“Much of the country was on a wartime footing during the period, with Mao growing increasingly feeble and tense relations with former ally the Soviet Union breaking out into border clashes. Radicals allied with the so-called "Gang of Four," consisting of Mao's wife Jiang Qing and her confederates, battled with those representing the party's old guard, who were desperate to end the chaos in the economy, schools and government institutions.” =

Idea Behind Working in the Countryside in the Cultural Revolution

The idea of encouraging urban educated youths to “go to work in the countryside” dates back to the early 1950s, when an idealistic Mao started to advocate that educated urban youths should go work in rural areas, seeing this a helpful measure to eventually eliminate the “three differences” (between workers and peasants, urban and rural, manual labor and mental labor). In Mao's opinion, only when these “three differences” were eliminated could the goal of communism be attained.” [Source: Sun Wukong and Wu Zhong, Asia Times, March 3, 2009]

In 1955, having read some reports about a few secondary high school graduates, then still very scarce, who volunteered to return to work in their native villages, an excited Mao wrote: “All intellectuals who can go to work in the countryside should happily do so. The countryside is a vast expanse of heaven and earth where one's career can flourish.”

But such a voluntary movement became a compulsory campaign during the Cultural Revolution. The campaign was launched under heartening revolutionary slogans at that time. However, retrospectively, people now realize that the practical purpose of the campaign, despite all of its “revolutionary” colors, was to curb urban unemployment. Under Mao's socialism, the government was responsible for providing jobs for people of working age.

With the Chinese economy on the verge of bankruptcy, there was no way for the government to create new opportunities to meet the growing needs of its people, as those who were born in the baby boom years in the early 1950s began to reach working age. Universities had not begun to enroll new high school graduates until the late-1970s. Had the universities enrolled new students, it would not have helped with the situation much anyhow as the tertiary educational institutions at that time could only take a very small proportion of high school graduates. [Ibid]

Down to The Countryside Movement

July 27, 1968: The military is dispatched to restore order and urban youth are sent down to the countryside, ostensibly to spread revolution and learn from the nation's peasantry. Over the next seven years, 12 million young Chinese are rusticated, a number equivalent to about 10 percent of the urban population. [Source: Associated Press, June 2, 2016 \^/]

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: The Down to the Countryside Movement was a massive relocation program that ultimately sent over 17 million young urban Chinese into rural areas across the country between 1968 and 1980. While some of these “sent-down youth” left the cities voluntarily, the vast majority were coerced against their will. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

“Due to a variety of factors, including urban unemployment and the Cultural Revolution’s disruption of the education system, Mao Tse-tung proclaimed in 1968 that it was “very necessary for the educated youth to go to the countryside and undergo reeducation by the poor peasants. Ideally, the relocation program would cultivate the sent-down youth’s commitment to party ideology and foster economic growth in underdeveloped areas. The young urbanites, fresh from high school, university, and even elementary school, were forced to endure backbreaking labor jobs and the extreme poverty common in the countryside at the time. Although some of the youth saw the policy as a great opportunity for adventure or patriotism, others resented the harsh work and poor living conditions and yearned to return home.-

“Most of the sent-down youth did eventually return home, but the many years they spent in the countryside remained lost. They’ve become known as a lost generation, an immense group of people who were denied the chance to finish school and maximize their potential. As one Beijing history professor put it, “From the perspective of a historian, from the perspective of the entire nation’s development, this period must of course be negated.” -

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: In 1979, three years after the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping visited the United States. At a state banquet, he was seated near the actress Shirley MacLaine, who told Deng how impressed she had been on a trip to China some years earlier. She recalled her conversation with a scientist who said that he was grateful to Mao Zedong for removing him from his campus and sending him, as Mao did millions of other intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, to toil on a farm. Deng replied, “He was lying.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, May 6, 2016]

Participating in the Down to The Countryside Movement

Tracy You of CNN wrote: “Hu Rongfen had no choice. On November 14, 1971, in the whirlwind of Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, the slender and soft-spoken middle school graduate was dispatched from Shanghai to a far-flung village in East China's Anhui Province to work in the country. This wasn't a punishment for any wrongdoing — on the contrary, the quiet girl was a top student in class. The migration was an order from the central government to every urban household — at least one of their teenage children needed to leave the city to work on the farm indefinitely.[Source: Tracy You, CNN, October 25, 2012 ~|~]

“The ruthless political command lasted from 1966 until the mid-1970s and intended that the privileged urban "intellectual" youth learn from farmers and workers. As a result, China's "lost generation" emerged — deprived of the chance of education and the right to live with their families.“We were told that city dwellers never move their limbs and could not distinguish different crops," says Hu. "So we were banished to labor and learn skills and grit from peasants." Hu spent four years (1971-1974) planting rice, spreading cow dung and chopping wood in Jin Xian, a mountainous county.~|~

Known in Chinese as "up to the mountains and down to the farms," the urban-to-rural youth migration was part of China's decade-long Cultural Revolution. “Hu still remembers the luggage she brought: basic life necessities, the "Little Red Book" explaining Chairman Mao's theories — a mandatory read for everybody — and dozens of notebooks with hand-copied chapters from "Jane Eyre" and "Anna Karenina," which she sneaked in secretly — these books had been banned for their perceived Capitalist connotations. “I used to read those notebooks in secret under my blanket at midnight.", According to Chinese media, as many as 17 million "intellectual youths" in the country packed their bags and moved to some of the remotest parts of China. There, they transformed from care-free students to farmers. “I still can't bear to recall my youth spent on the farm," she says.~|~

“One of Hu's most vivid memories was working in rice fields in early spring in freezing water, on which lumps of ice still floated. There, she would bend down to seed for more than ten hours. She would slap her legs madly to rid herself of the leeches clinging to her limbs. Blood would ooze from her wounds and mingle with the dirt and water. Another time, she recalled walking 40 kilometers along mud paths against bone-chilling winds to the nearest bus station on Chinese New Year's Eve to catch a ride to the train station to go back to Shanghai to see her parents. Hu was eventually elected by her commune to study mechanics at a college in Hefei — the capital of Anhui — in 1974. Most people stayed as long as eight years in their commune and only started returning to cities from 1978 onwards. Many did not get a chance to return to their studies.~|~

Surviving the Down to the Countryside Movement

On a reunion for the class of a rural middle school in eastern China in which many of the students were forced to work in the countryside,one participant wrote: “In May of 1966 school was suspended. Turmoil erupted. Over the next decade everyone in the class experienced 2-9 years’ working on farm communes. They all shared miserable first years, as the villagers who worked the farms had nothing but contempt for “city slicker,” soft-handed people who didn’t know one end of a hoe from the other. They got the worst jobs on the farms. They literally shovelled shit for a year or two.

“If they learned anything from the Cultural Revolution, this group labelled “Intellectuals” because of their education level learned perseverance and tact; they kept their heads down and separately found ways to survive the political climate. Their life stories differ in detail, but have common threads of determination and a certain ability to avoid noticing obvious things out of the corners of their eyes.

“To this day they share a habit that I have noticed in a lot of Chinese individuals of a certain age group. When saying something even slightly confidential or personal they cover their mouth with their hands to prevent any outside observers from reading their lips. They tend to speak the truth out of the side of their mouths.”

Surviving the Down to the Countryside Movement in Different Ways

The down to the countryside participant wrote: As a group, they all survived their time in the hinterlands on the farming communes. Almost half of them returned ultimately to their home town. The rest are scattered from Heilongjiang to Sichuan to Beijing to Shanghai.The fellow who organized the reunion was, fifty years ago, the class clown. He was sent to the same farming commune that three others of the class were also sent to. The other three got away from the farm fairly quickly. One married a well-connected bureaucrat (he was in high school and his dad was a senior Party member at the time, so he was protected). Today she is sophisticated, well-dressed and drives a BMW. Mr. W, on the other hand, was stuck on the farm until 1975 when he was able to get a job with a big city government. He stayed in government service and rose to the position of Secretary to the Mayor’s Office.

“The Class Monitor of 1966 was sent to a farm but with his charm was able to leave the hinterlands in less than 2 years and join the PLA. His career path might have been predictable. He was successful. He is a “take charge” guy, but wouldn’t reveal to me where he spent his time in the army. When he retired from the PLA he was recruited by the Public Security Bureau where he rose to a very senior level, being responsible for aspects of security for President Bill Clinton’s visit to China. He now lives very comfortably on two pensions: one from the PLA and one from the PSB.

“Three of the ladies in this group spent 30+ years as primary school teachers, all now retired and living on generous pensions. They were able to become teachers because, although they had not officially completed 9th grade, they were highly educated when compared to their peers. Another of the group was well-liked by his farm community and when the opportunity arose they recommended him for a position in the Water Department of a municipality. He was known for troubleshooting and his problem-solving abilities. In fact, the other students mutually agreed that this was the guy from this class that would go to high school and ultimately to TsingHua or Beijing University, he was that bright. Instead he ended up with the City Water Department. He retired as Chief Engineer of the Water Department for his municipality; but, he is so valuable at his craft that they immediately re-hired him as a consultant to the Department. So, now he gets retirement pay plus another salary. Double dipping is not limited to the US Government.”

Impact of the Down to the Countryside Movement on Villagers

Reporting from Inner Mongolia, Jim Yardley wrote in New York Times: “Laoshidan is decrepit, with battered brick homes, mud stables and dirt paths for roads. During the Cultural Revolution, Laoshidan was one of the thousands of rural villages that housed city youths “sent down” to work with peasants in the countryside. “They couldn’t do anything, ” recalled Gao Zhenlin, a woman with brown teeth and a cockeyed baseball cap who has lived in the village for almost 30 years. “They were incapable. They didn’t know how to farm.” But the end of the Cultural Revolution meant the city kids could return to the city, and they left immediately. [Source: Jim Yardley, New York Times, December 2, 2006]

Fuxian Yi, a demographer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was born in a village in Qianyang County, Hunan Province. He told the New York Times: “The Cultural Revolution was without question a disaster for China, but far less damage was done in those 10 years than in the Great Leap Forward or 40 years of family planning. In the countryside where I am from, there was relatively speaking less suffering, and there was even good from it. Young urbanites “sent down” to teach us raised the educational level. My elementary school teacher in the village was a “sent down youth” from a local city in Hunan. She was a very good teacher. [Source: “Voices from China’s Cultural Revolution”, Chris Buckley, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, Jane Perlez and Amy Qin, New York Times, May 16, 2016 ~~]

“Infant mortality was high and life expectancy low, and the “barefoot doctor” system that spread at that time brought down mortality fast, by introducing things like basic hygiene. A grandfather in my extended family had eight children in the 1940s and ’50s. Only one lived. My uncle had eight children in the 1950s and ’60s. Four lived. My own older brother and older sister died a few days after birth, but by the time I was born, in 1969, the infant mortality rate had fallen. So I lived.” ~~

Xi Jinping Sent-Down to a Cave Home in Shaanxi

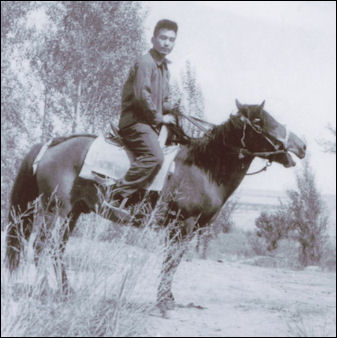

Xi Jinping in Shaanxi Province

Xi Jinping was too young to be an official Red Guardwas detained “three or four times” by groups of Red Guards, and forced to denounce his father. In 1969, fifteen-year-old Xi Jinping was sent with 15 other teenagers from military families to Liangjiahe, a village flanked by yellow cliffs and yellow hills in Shaanxi Province as part of Mao's campaign to toughen up educated urban youth during the chaotic Cultural Revolution. The area was remote and bleak. He had to put up with fleas and hard labor. He worked on a farm and later said he was so incompetent that other laborers rated him a six on a ten-point scale, “not even as high as the women." “The intensity of the labor shocked me," Xi said in a 2004 television interview. To avoid work, he began smoking because nobody bothered a man smoking and took long bathroom breaks. After three months, he fled to Beijing, but he was arrested and sent to a labor camp for six months. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ]

Xi was one of millions of Chinese youths driven into the countryside by Mao Tse-tung but he had the advantage of being a region where his father had helped to establish a base for Communist forces in the 1930s. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Élite families sent their children to regions that had allies or family, and Xi went to his father's old stronghold in Shaanxi. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

Barbara Demick and David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “For nearly seven years, Xi Jinping lived there, making a cave his home. A thin quilt spread on bricks was his bed, a bucket was his toilet. Dinners were a porridge of millet and raw grain. "He ate bitterness like the rest of us," said one of the Liangjiahe farmers, Shi Yujiong, who was 25 years old when the teenager arrived. [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

Liangjiahe is a tiny community of cave dwellings dug into arid hills and cliffs and fronted by dried mud walls with wooden lattice entryways. Xi helped to build irrigation ditches and lived in a cave home for three years. "I ate a lot more bitterness than most people," Xi said in a rare 2001 interview with a Chinese magazine. “Knives are sharpened on the stone. People are refined through hardship. Whenever I later encountered trouble, I’d just think of how hard it had been to get things done back then and nothing would then seem difficult." [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

The Liangjiahe years are one of the most detailed accounts of Xi's life and personality partly because he himself chronicled them as a formative experience. In a 1998 essay titled "Son of the Yellow Earth," Xi wrote: "I was rather casual at first. The villagers had an impression of me as a guy who doesn't like to work hard." He said after he ran away to Beijing he was arrested during a crackdown on deserters and sent to a work camp to dig ditches. Xi later returned to the village, and this time he worked harder. His pale skin darkened and he carried heavy buckets of water from the well. He devised a biogas pit that converted waste into energy. "Xi has an advantage," Zhang Musheng, a former government official who knew Xi said. "He lived at the bottom for a long period. It makes him understand the current conditions in China very well."

See Separate Article XI JINPING'S EARLY LIFE, CHARACTER AND CAVE HOME YEARS factsanddetails.com

After the Down to the Countryside Movement

Explaining how the Cultural Revolution led to blossoming of artistic experimentation and intellectual dissent after the movement was over. Guobin Yang, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times: After the former Red Guards and other Chinese youth “were sent down to villages from late 1967, disillusionment deepened. They also saw a China unknown to them before, very poor and harsh. Many people used family connections or feigned illness to try to move back to cities. The more intellectually oriented ones thought and wrote about their experiences in poems, stories, letters and diaries. Throughout the ’70s, people like the now famous painter Xu Bing practiced their art after a day’s labor tilling the fields. Some entertained themselves by circulating hand-copied manuscripts of spy stories or erotic literature. Others took to singing romantic songs, especially Russian folk songs. The most apolitical kind of activity, like singing a love song, was an expression of political dissent, because it was a rejection of politics when politics was supposed to be “in command” of everything. “These were small things, small but happening more and more often, in more and more places. Together, they made up the undercurrent that eroded the ideology of the Cultural Revolution and primed Chinese society for radical economic and political change when opportunities arose. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 15, 2016].

Former President Hu Jintao

in Guizhou The down to the countryside participant wrote: In the mid-1970s when the Party power brokers finally sorted themselves out and Deng Xiao Ping took control, the damage done to the country by ruination of the national education system was recognized. The pool of educated people had shrunk to the extent that Deng announced that anyone with a high school diploma would be automatically assumed to have passed the Gaokao and qualified to attend university. People of my wife’s group, middle school graduates, were near the top of their generation in terms of education. They were in demand!

“Essentially all members of this group spent their lifetimes working for government. Government jobs were made available to these people partly as “compensation” for the time they spent on farm communes or other injustices. But more importantly, as Deng Xiao Ping began to force change, these people were in high demand as some of the most educated people in the working population.

“None of the Reunion attendees engaged in any private enterprise – they did not need to do so. As well, political caution held them back. Now they are all more-or-less retired and living on ample government pensions. Privately, a few people told me they blamed the Gang of Four for their lives’ disruptions. Publicly nobody blamed anybody. The attitude seemed to be that circumstances were not controllable, life is tough, and you just get on with things and work through problems. Don’t blame anyone. Keep your head down. The past is past. This group of people – aged 65-70 – without exception revere Mao Tse Tung as the Founder of today’s nation. They do not blame him for the Cultural Revolution. At parties, on the busses, and at gatherings we had during nearly a week’s events, people in the group would spontaneously break into song, some of the so-called “Red” patriotic songs of old, and everyone would join in with gusto, with cheers and salutes and bonhomie. No one had the time or interest to dwell on past misfortunes.”

Impact of the Countryside Movement

Wen Jiabao Tracy You of CNN wrote: “Hu eventually found a job in Hefei after graduation and lived there until 1986 before moving back to her hometown for good. She worked as an office secretary at a scientific laboratory in Shanghai until her retirement in 2008. But the memories from her youth still make Hu blanch. If the Cultural Revolution came back and I were to be dispatched again, I'd rather commit suicide," she says, noting that the farming days tortured her physically and mentally. "I stayed awake night after night at the commune, worrying if I'd ever return to any city. After my retirement, I seize every opportunity to travel and exercise my body (to stay healthy)," she adds. “I live a happy life now. I want to live every day like (I were still in my) youth because I was never able to enjoy my teens and 20s — the best time of one's life." However, she confesses she did gain something — an iron will to live through the toughest conditions and four lifelong friends. [Source: Tracy You, CNN, October 25, 2012 ~|~]

“Hu and her four dormmates on the farm have stayed in regular contact for the past four decades. Having experienced similar ordeals in youth, they encourage and support each other to enjoy the present and the future. They write memoirs, travel stories and nostalgic poems to share with each other or post to the web. “It's a way for us to act out our feelings towards the past," she says.^^ “Together my 'comrade sisters' and I lived through some unimaginably tough times — learning to live without parents and like peasants," says Hu. “And now we want to live our youth again all together." ~|~

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; Photos: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Wen and Hu pictures China.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021