XI JINPING 'S PARENTS AND BIRTH

Xi Jinping's parents

Xi Jinping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or CPC) in November 2012. He became Chinese president in March 2013 and over time claimed other titles to become China’s unquestioned leader to such a degree he has been called a new Mao and a new Emperor. Xi was officially anointed as the new leader of China, succeeding Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), at its 18th Congress in November 2012. He officially took the position in early 2013.

Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker: “In the summer of 1943, a fresh-faced student leader, recently dispatched to the town of Suide in northeast China, caught the eye of its local Communist Party Secretary. “He was walking downhill and I was walking uphill, and when I saw him, all I could do was perform a nervous army salute,” Qi Xin, the student leader, recounted later. By that winter, as acquaintance grew into courtship, the cadre, Xi Zhongxun, would ask the seventeen-year-old Qi to marry him, though not before requesting of his young bride a confession-style “autobiography” first. The fifty-five-year-long marriage that resulted survived decades of political unrest, and produced Xi Jinping, China’s President-in-waiting. [Source: Jiayang Fan, The New Yorker, February 23, 2012]

Xi Jinping (the family name is pronounced Shee) was born June 1, 1953, the son of revolutionary war hero and Long March veteran Xi Zhongxun. He was the third of four children born to the elder Xi's second wife. When he was a young child, his father was named vice premier, and the family moved into Zhongnanhai, the vermilion-walled Communist Party compound next to the Forbidden City, home of the late emperors. [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

Xi started life near the top. When he was born his father Xi Zhongxun was China’s propaganda minister. Later he would serve as China's Vice Premier. John Garnaut wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald, “Xi grew up in a household steeped in the communist ideals of equality, personal austerity and the emancipation of all mankind. Resurrecting Mao symbolised old ideals while reminding people of the contributions their families made to the founding of the People's Republic of China. [Source: John Garnaut. Sydney Morning Herald, August 22, 2013]

See Separate Article XI JINPING’S FAMILY: HIS REVOLUTIONARY FATHER, HARVARD-EDUCATED DAUGHTER AND WEALTHY SIBLINGS factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: XI JINPING factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FAMILY, HARVARD EDUCATED DAUGHTER AND FAMILY WEALTH factsanddetails.com; PENG LIYUAN: XI XINPING'S WIFE AND CHINA’S GLAMOROUS FIRST LADY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S POLITICAL CAREER AND RISE IN THE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BEFORE HE BECAME THE LEADER OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BECOMES THE LEADER OF CHINA: HIS INNER CIRCLE, STYLE AND DIRECTIONS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S AUTHORITARIANISM AND TIGHT GRIP ON POWER factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S STYLE, LEADERSHIP AND PERSONALITY CULT factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S DOMESTIC POLICY: CHINESE DREAM, ECONOMICS AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, MAOISM AND CONFUCIUS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S ANTI-CORRUPTION DRIVE factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, HUMAN RIGHTS AND OPPOSITION TO WESTERN IDEAS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, THE MEDIA AND THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF HIM factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com; LI KEQIANG factsanddetails.com; CHINA'S POLITBURO STANDING COMMITTEE MEMBERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future” by Chun Han Wong Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China” (English Version) by the Chinese government Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018" by Alfred L. Chan Amazon.com; “CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Xi: A Study in Power: A Study in Power” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Snake Oil: How Xi Jinping Shut Down the World” by Michael P Senger Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping” by Willy Lam Amazon.com; “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” by François Bougon Amazon.com

Xi Jinping’s Early Life

Xi with father Xi Zhongxun As son of Xi Zhongxun, the younger Xi grew up in Beijing in the 1950s in a comfortable home when most Chinese were desperately poor. He went to China's premier military-run high school. Xi's family had their own cook and nannies, a driver and a Russian-made car, a telephone, a special supply of food earmarked for the leadership. Fearful of spoiling the children, the elder Xi made his son wear his sisters' hand-me-down clothing and shoes, which the family dyed so they wouldn't be in girlish colors, according to a government-authorized biography.

Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker: Born "four years after the declaration of the People’s Republic, Xi spent his early years as the son of the Vice-Premier, living in vermilion-walled Zhongnanhai, the Communist leaders’ own plush and private Forbidden City. From the tinted windows of his father’s chauffeured sedan, the war-torn Republic outside his gated home must have looked as strange as a foreign country. But when Xi turned nine, his father fell out of favor with his former colleague."

But in 1962, Xi's father had a falling out with Mao and went to prison. The family was booted from their compound, forced to move around Beijing. "You grow up in an environment where everything is provided, and suddenly you're stripped naked and left in the cold," said a friend from Xi's younger days. The friend, who did not want to be quoted by name when discussing the leadership, described a world in which suddenly adrift teenagers would collect books left unguarded in libraries or discarded by people who feared persecution as intellectuals. "We had nothing to do to comfort ourselves but read," said the friend.

When the Cultural Revolution started in 1966 the whole Xi family was punished for their father's alleged sins. Xi's mother was sent to a work camp in the countryside and Xi' Jinping's school was closed down and he was "sent down" to the countryside. Xi has described Mao's orders that intellectual youths be sent to the countryside as a welcome relief. He was sent to Liangjiahe, hundreds of miles southwest of Beijing and in Shaanxi province, his father's base in revolutionary days.

Xi Jinping’s at an Elite Princeling School

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “When Xi Jinping was five, his father was promoted to Vice-Premier, and the son often visited him at Zhongnanhai, the secluded compound for top leaders. Xi was admitted to the exclusive August 1st School, named for the date of a famous Communist victory. The school, which occupied the former palace of a Qing Dynasty prince, was nicknamed the lingxiu yaolan—the “cradle of leaders.” The students formed a small, close-knit élite; they lived in the same compounds, summered at the same retreats, and shared a sense of noblesse oblige. For centuries before the People’s Republic, an evolving list of élite clans combined wealth and politics. Some sons handled business; others pursued high office. Winners changed over time, and, when Communist leaders prevailed, in 1949, they acquired the mantle. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

“The common language used to describe this was that they had ‘won over tianxia’—‘all under Heaven,’ ” Yang Guobin, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. “They believed they had a natural claim to leadership. They owned it. And their children thought, naturally, they themselves would be, and should be, the future owners.” As the historian Mi Hedu observes in his 1993 book, “The Red Guard Generation,” students at the August 1st School “compared one another on the basis of whose father had a higher rank, whose father rode in a better car. Some would say, ‘Obey whoever’s father has the highest position.’ ” ^^^

When the Cultural Revolution began, in 1966, Beijing students who were zilaihong (“born red”) promoted a slogan: “If the father is a hero, the son is also a hero; if the father is a reactionary, the son is a bastard.” Red Guards sought to cleanse the capital of opposition, to make it “as pure and clean as crystal,” they said. From late August to late September, 1966, nearly two thousand people were killed in Beijing, and at least forty-nine hundred historical sites were damaged or destroyed, according to Yiching Wu, the author of “The Cultural Revolution at the Margins.” ^^^

Xi Jinping During the Cultural Revolution

Back to the Countryside Movement during the Cultural Revolution

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, Xi Jinping “was too young to be an official Red Guard, and his father’s status made him undesirable. Moreover, being born red was becoming a liability. Élite academies were accused of being xiao baota—“little treasure pagodas”—and shut down. Xi and the sons of other targeted officials stayed together, getting into street fights and swiping books from shuttered libraries. Later, Xi described that period as a dystopian collapse of control. He was detained “three or four times” by groups of Red Guards, and forced to denounce his father. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

In 2000, Xi Jinping told the journalist Yang Xiaohuai about being captured by a group loyal to the wife of the head of China’s secret police: “I was only fourteen. The Red Guards asked, ‘How serious do you yourself think your crimes are?’” Xi said “You can estimate it yourselves. Is it enough to execute me?” The Red Guards replied, “We can execute you a hundred times.” Xi said: “To my mind there was no difference between being executed a hundred times or once, so why be afraid of a hundred times? The Red Guards wanted to scare me, saying that now I was to feel the democratic dictatorship of the people, and that I only had five minutes left. But in the end, they told me, instead, to read quotations from Chairman Mao every day until late at night. ^^^

Xi’s older half-sister Xi Heping died. Australian journalist John Garnaut, author of book on Xi Jinping told The New Yorker, “It was suicide. Close associates have said to me, on the record, that after a decade of persecution she hanged herself from a shower rail.” ^^^

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: During the Cultural Revolution, Xi’s peers, other “princeling” children of high-ranking Chinese Communist Party leaders whose parents hadn’t been purged, were rampaging through Beijing as Red Guards, given power to torture and often kill teachers, intellectuals and authority figures. They believed they were bringing about utopia. Xi was not allowed to join them, even as he saw himself as a true party disciple. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

“Some scholars suggest that the shame of that period pushed Xi not to question or renounce the extremities of Mao’s leadership, but to prove himself worthy to lead. “He sees himself as the legitimate successor of the CCP red dynasty by blood,” said Yinghong Cheng, a professor of history at Delaware State University. Many princelings of Xi’s generation regard state power as their “family inheritance,” Cheng said. “They are entitled to it, must hold it firm, and losing it means losing everything.”

Most of Xi's generation were idealists when they were young, said a prominent Chinese historian who also spent years as a “sent-down youth” and asked not to use his name for protection. But for him and many liberal intellectuals, returning to university in 1977, after Mao died and the Cultural Revolution ended, sparked a painstaking reassessment. “Everything I’d built on — Marx, Lenin, Mao — they were all wrong. I needed to adjust from the roots, to spit out that wolf’s milk we had all drunk,” the historian said. “Inch by inch, you rebuild your worldview. It takes decades to become cleareyed, to say, ‘Where did we go wrong? What is China? Who are we?’”

Xi Jinping’s Cave Home Years

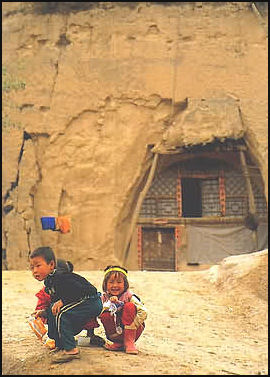

Liangjiahe (two hours from Yenan, where Mao finished the Long March) is where Xi Jinping spent seven years during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s. He was one of millions of city youths "sent down" to the China countryside to work and "learn from the peasants" but also to reduce urban unemployment and reduce the violence and revolutionary activity of radical student groups. .[Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Liangjiahe is a tiny community of cave dwellings dug into arid hills and cliffs and fronted by dried mud walls with wooden lattice entryways. Xi helped to build irrigation ditches and lived in a cave home for three years. "I ate a lot more bitterness than most people," Xi said in a rare 2001 interview with a Chinese magazine. “Knives are sharpened on the stone. People are refined through hardship. Whenever I later encountered trouble, I’d just think of how hard it had been to get things done back then and nothing would then seem difficult.” [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times: “Turning a leader’s former home into a tableau for propagating his political-creation myth has a venerable precedent in the People’s Republic. Back in the 1960s, Mao’s birthplace, Shaoshan, was turned into a secular shrine for slogan-chanting Red Guards who looked on modern China’s founder as a nearly godlike figure. The devotion at Liangjiahe falls far short of the fervent cult of personality that Mao ignited. Even so, Mr. Xi stands out for turning his own biography into an object of adoration, and zeal. Neither of Mr. Xi’s recent predecessors as leader, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, could tout a similarly dramatic tale of coming of age in a dim, flea-infested cave. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 8, 2017]

“But more than that, Mr. Xi’s story embodies the authoritarian values he wants to restore in China — a “red-brown” melding of Communist revivalism and earthy nationalism rooted in a glorified rendering of China’s ancient past. Liberal-minded members of China’s middle class bridle at that ideology. But others, including farmers and blue-collar workers, find a lot to like in Mr. Xi’s appeals to patriotic pride and homespun populism.This story line resonates with many of the nearly 18 million Chinese who were also sent to the countryside by Mao in a mass effort to re-educate urban youth in the rustic virtues of China’s peasant majority, while defusing the fanaticism of the Red Guards. This so-called sent-down generation now holds the reins of the Communist Party, including four spots on the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s highest rung of power.Members of that generation said Mr. Xi shared not only their experiences, but also their values of frugality and perseverance. They said that these had been lost in younger Chinese, especially those in urban centers like Beijing, who grew up after their nation’s economic takeoff.

“Just as Shaoshan did for Mao, Liangjiahe has come to figure prominently in Mr. Xi’s official biography. When he arrived at the age of 15 in early 1969, as one of millions of Chinese youth sent to the countryside by Mao, the village’s 360 residents lived in caves dug into the dry, ocher-colored hillsides, and eked a meager existence out of the dusty soil. According to the current narrative, Mr. Xi showed his first signs of greatness in the then-penniless village, rising to a position of local party leadership.

Xi Jinping’s Cave Home Story

In 1969, fifteen-year-old Xi Jinping was sent with 15 other teenagers from military families to to Liangjiahe, a village flanked by yellow cliffs and yellow hills in Shaanxi Province as part of Mao’s campaign to toughen up educated urban youth during the chaotic Cultural Revolution. The area was remote and bleak. He had to put up with fleas and hard labor.

Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times: In a 2004 interview, given when Mr. Xi was still an obscure provincial official, he recalled being glad to go to Liangjiahe because Beijing was more dangerous. “On the entire train everyone was crying, but I was smiling,” he said. “If I didn’t leave, I didn’t even know if I’d survive.”After three days of travel by train, truck and foot, Mr. Xi and 14 other youths reached the village, where they were shocked by the levels of poverty. They also suffered an infestation of fleas that left their bodies covered in sores. Mr. Xi said that after a few months he could not cope and returned to Beijing, which the official narrative neglects to mention. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 8, 2017]

Xi worked on a farm and later said he was so incompetent that other laborers rated him a six on a ten-point scale, “not even as high as the women.” “The intensity of the labor shocked me,” Xi said the 2004 television interview. To avoid work, he began smoking because nobody bothered a man smoking and took long bathroom breaks. After three months, he fled to Beijing, but he was arrested and sent to a labor camp for six months.

Xi Jinping in Shaanxi

Xi spent his seven years in Shaanxi, one of China’s poorest provinces. He was one of 30 million Chinese youths forced into the countryside by Mao Zedong but he had the advantage of being a region where his father had helped to establish a base for Communist forces in the 1930s. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Élite families sent their children to regions that had allies or family, and Xi went to his father’s old stronghold in Shaanxi. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

In Shaanxi, Xi he slept on a brick bed and ate raw-grain gruel. Barbara Demick and David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, A thin quilt spread on bricks was his bed, a bucket was his toilet. Dinners were a porridge of millet and raw grain. "He ate bitterness like the rest of us," said one of the Liangjiahe farmers, Shi Yujiong, who was 25 years old when the teenager arrived. [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

In “The Goverance of China”, a 500-page compilation of speeches, main points of speeches and interviews and biographical data on Xi Jinping produced by different parts of the Chinese government bureaucracy, Xi said he was “able to walk for 5 kilometers on a mountainous path with two dangling baskets filled with almost one hundred kg of wheat on a shoulder-pole.” He also exchanged a motorized tricycle he won after being named a model educated youth for a “walking tractor, a flour milling machine, a wheat winnowing machine, and a water pump to benefit the villagers”. Local people remember him as “reading books as thick as bricks while herding sheep on mountain slopes or under a kerosene lamp at night” [Source: Elizabeth Economy, Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog, Forbes, October ct 15, 2014]

Villagers Recall Xi Jinping’s Cave Home Years

The myth — or perhaps the real story — goes that Xi started out his cave home year weak and lazy but by the end of his years of hard labor and village life had developed a taste for the pickled vegetables of peasants and leadership skills. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Liangjiahe villagers recall Xi as a gangly bookworm who eventually earned their respect. They said Xi spent his days working in the fields and his evenings reading by the light of a kerosene lamp. They said he was a passionate reader who became annoyed if anyone touched his books. Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “Most villagers recall a teen workaholic, digging ditches in trousers held up with blasting fuse, his pale skin slowly tanning in the sun... Xi adapted to the loneliness of life in a cave, read books on Marxism, chemistry and mathematics late into the night...His cave home, still occupied by a farming family, became the village meeting spot. His experiments with biogas - run from pig manure - were replicated across the area and produced cooking fuel for scores of homes. When he left, said one villager, everyone wanted to invite him to their caves to host his final dinner in Liangjiahe. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, November 3, 2012]

Xinhua reported Xi helped transform the villagers’ lives by organizing a cooperative for blacksmiths. “He arrived in the village as a slightly lost teenager and left as a 22-year-old man determined to do something for the people,” Xinhua said. Chai Chunyi, a 63-year-old villager, told the Los Angeles Times Xi arrived as a clueless city boy, lugging a heavy suitcase full of books. "At first, we couldn't understand his accent and he couldn't understand us," Chai said. "But he worked really hard. He didn't complain like some of the others from the city." "When he first arrived, he wasn't that impressive," a villager who gave his name as Gong, told The Times. He said, "He once taught us how to grow tobacco, but it wasn't very successful at all. Nobody grows tobacco here now. We just raise pigs." “He was always very sincere and worked hard alongside us. He was also a big reader of really thick books,” Shi Chunyang, then a friend of Xi and now a local official, told AP.

Xi Jinping “Reborn” a Leader in the Countryside

Xi Jinping's cave home

Xi’s Liangjiahe years and his “rebrith” there later became the centerpiece of his official narrative the Communist Party spun of him being a tireless, selfless volunteer. Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “Liangjiahe, with its life of hard labour, remains a vital part of the official image-building: he arrived with the "princeling" credentials of the elite, as the son of one of Chairman Mao's closest revolutionary colleagues. But, by villagers' accounts, he stoically "ate bitterness" with the peasantry. "Of course we never guessed he would lead China, but from what we know of him in Liangjiahe, I think he could be a good leader," one villager said. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, November 3, 2012]

According to a Xinhua article: “Xi lived in a cave dwelling with villagers, slept on a kang, a traditional Chinese bed made of bricks and clay, endured flea bites, carried manure, built dams and repaired roads.” Liangjiahe is located in the Yan’an area of Shaanxi, where Mao and other top revolutionaries, including Xi’s father, settled after the Long March and plotted their takeover of China. Xi often said that his years in Yan’an made him into who he is as an adult. “Yan’an is the starting point of my life,” he said in 2007. “Many of the fundamental ideas and qualities I have today were formed in Yan’an.”

In the 2004 interview, Xi described his years in Liangjiahe with deep affection. Enduring the fleas, rough beds and unvarying food made him grow up. He said “To start with, I was a square peg in a round hole. Just after I first arrived, I saw our cave home on a hillside, with the twinkling kerosene lamps, and I said to my classmates, ‘Does it feel like to you that this is like cave men?...But later we lived in this environment for seven years.” [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, February 13, 2015]

Even at that early age, the party narrative goes, Xi showed leadership skills. “When people had a conflict with each other, they would go to him, and he’d say, Come back in two days,”Lu Nengzhong, the patriarch of a cave home where Mr. Xi lived for three years,” told the New York Times. “By then, the problem had solved itself.” Xi came to hate ideological struggles. In an essay published in 2003, he wrote, “Much of my pragmatic thinking took root back then, and still exerts a constant influence on me.”

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, By the time he was recommended in 1975 for a place to study at Tsinghua University in Beijing, Mr Xi had established himself as a key figure in the village and a young man of considerable charisma. "His performance was outstanding," said one Liangjiahe resident. "He went to nearby villages to organise meetings and study sessions. Before long, he became our village party secretary." [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, November 3, 2012]

Impact of the Cave Home Years on Xi Jinping

The Liangjiahe years are one of the most detailed accounts of Xi’s life and personality partly because he himself chronicled them as a formative experience. In a 1998 essay titled "Son of the Yellow Earth," Xi wrote: "I was rather casual at first. The villagers had an impression of me as a guy who doesn't like to work hard." He said after he ran away to Beijing he was arrested during a crackdown on deserters and sent to a work camp to dig ditches. Xi later returned to the village, and this time he worked harder. His pale skin darkened and he carried heavy buckets of water from the well. He devised a biogas pit that converted waste into energy. "Xi has an advantage," Zhang Musheng, a former government official who knew Xi said. "He lived at the bottom for a long period. It makes him understand the current conditions in China very well." [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

The Liangjiahe years are one of the most detailed accounts of Xi’s life and personality partly because he himself chronicled them as a formative experience. In a 1998 essay titled "Son of the Yellow Earth," Xi wrote: "I was rather casual at first. The villagers had an impression of me as a guy who doesn't like to work hard." He said after he ran away to Beijing he was arrested during a crackdown on deserters and sent to a work camp to dig ditches. Xi later returned to the village, and this time he worked harder. His pale skin darkened and he carried heavy buckets of water from the well. He devised a biogas pit that converted waste into energy. "Xi has an advantage," Zhang Musheng, a former government official who knew Xi said. "He lived at the bottom for a long period. It makes him understand the current conditions in China very well." [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker: “In talking about the experience in recent years, Xi has, without denying the hardships he endured, chosen to characterize those years as a welcome relief. It’s this sort of willingness to suffer through disparate circumstances with a smile that seems to have enabled Xi to work his way back up the Party ladder. Indeed, by the time he rose to the coveted position of Politburo Standing Committee member, he had nothing and everything in common with his eight colleagues there; whereas they uniformly came from one of two backgrounds—poverty or privilege—he had arisen from both. [Source: Jiayang Fan, The New Yorker, February 23, 2012 +/+]

“What kind of man does such an experience make? Do the traits that help a person survive also allow him to thrive as a leader? Here, I can’t help but think of Wang Meng, China’s best-known writer, who emerged from the country’s political turbulence into a prominence shaped as much by his adherence to state politics as by his powerlessness to escape them.” +/+

Xi Jinping's Cave Hometown Today

Xi returned to Liangjiahe only once, in 1993, when he gave an alarm clock to each household. In Liangjiahe today, the older people who knew Xi are proud and hopeful about his ascension. According to the Los Angeles Times:The village remains poor, but with many new comforts: electricity, running water and a road that residents say was paved because of Xi's intercession. He had remained in touch with some of the villagers, helping the disabled son of one of his hosts get an operation on his leg. In 1993, he came back to visit, bringing with him a gift of watches. "He had enough watches for each household to get one," said villager Chai. "But the party secretary in the village took some of them, so many houses didn't get them." [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

Inside a cave house today On Liangjiahe today, Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “In the remote hamlet of Liangjiahe, tucked among the parched mountains of China's northwest Shaanxi province, the corn harvest is in, firewood has been gathered for winter and the lanes are usually quiet. But on the winding approach road, activity is frenetic. Five work parties are laying a new surface and a huge bridge is being built to bear the future stream of traffic. When the Communist Party appoints China's new leader, Liangjiahe will be known as the village where Xi Jinping’s character was honed by rural hardship. Residents are expecting tourists. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, November 3, 2012]

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: Local Communist Party officials and police in Liangjiahe followed reporters on a visit and asked them to leave, showing how the party wants to control information about Xi’s past. But they did allow brief interviews, including with Shi, described by villagers as Xi’s former “iron buddy.” Shi stood across from the now-abandoned, one-room home where Xi lived with a local family, and recalled the day Xi departed at age 22. “No one wanted to see him go,” Shi said. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Xi Jinping Tourism in Liangjiahe

Reporting from Liangjiahe, Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times: “Years after Xi Jinping first trudged into this village as a cold, bewildered teenager, hundreds of political pilgrims retrace his footsteps every day. They follow a well-trod course designed to show how the seven years that the young Mr. Xi spent in this hardscrabble village in China’s barren northwest forged the strongman style that he now uses to rule the world’s most populous nation. Visitors peer down a well that Mr. Xi helped to dig, admire a storage pit that he built to turn manure into methane gas for stoves and lamps, and sit for inspirational lectures outside the cave homes where he sheltered from the chaos of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. ““When he first arrived in Liangjiahe, he wasn’t prepared for the hardship,” a guide told a tour group of officials, who listened attentively under a drizzling rain. The message, conveyed by the guides and the village’s carefully tended buildings and artifacts, is that Mr. Xi left Liangjiahe steeled for the leadership roles that he would one day assume.[Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 8, 2017]

“These days, Liangjiahe, which is about 380 miles southwest of Beijing, is thronged by officials, many of whom have been ordered to study Mr. Xi’s life. About 2,500 people visit Liangjiahe each day, People’s Daily reported, and many of them are ferried in on minibuses after paying a $3 ticket. (I was allowed to look around only after registering at the village police station, and was accompanied by a guard who whispered to villagers not to say anything.)"

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Tourists in matching red scarves visited a set of caves” where Xi reportedly lived. “Here is where the chairman ate coarse grain buns with the farmers," a guide said as a group of teachers from Guangzhou peered inside one of the caves. Newspaper cutouts with headlines about Mao and a photo of teenage Xi, slightly smiling into the distance, hung above rolled-up blankets and a straw mat on a raised mud platform. A bag of anti-flea powder sat prominently displayed on the window ledge, a testament to the fleabites young Xi endured.[Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

“A small museum weaves Xi's narrative with that of the Communist Party's benevolence, explaining that Xi read stories and dug wells for the villagers as a teenager, then charting the village’s recent rise in average income per person — from $25 a year in 1984 to $3,218 a year in 2019. The teachers from Guangzhou were all receiving required training as supervisors of the Young Pioneers, a Communist Party youth organization, and would then pass on the "red spirit" they'd acquired here to their students, one of the teachers said. When Xi speaks about his coming of age, he points to Liangjiahe. “Northern Shaanxi gave me a belief. You could say it set the path for the rest of my life,” Xi said in a 2004 interview with the People’s Daily.

Xi Jinping’s University Education

Xi Jinping is the only Chinese president to have a Ph.D. According to “The Goverance of China”, in the words of Elizabeth Economy of the Council on Foreign Relations:““Xi Jinping studied chemical engineering from 1975 to 1979, at the prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing but he never worked in a related field. He later majored in Marxist theory and ideological education at Tsinghua Humanities Institute. Xi Jinping is one of the few leaders in China who is educated in humanities and is the only Chinese president to have a Ph.D. [Source: Elizabeth Economy, Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog, Forbes, October ct 15, 2014. “The Goverance of China” is a 500-page compilation of speeches, main points of speeches of interviews and biographical data on Xi Jinping produced by different parts of the Chinese government bureaucracy.]

At the age of of 21, Xi enrolled at Tsinghua University, sometimes referred to a China's M.I.T., after his formal education was interrupted for seven years by the Cultural Revolution. He was admitted on the basis of political merit rather than test scores. Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Xi “left Liangjiahe for Tsinghua University in 1975 as a “worker-peasant-soldier” student, children with “red” class backgrounds who were nominated to return to school during the Cultural Revolution by their work teams. Chosen for their good performance in Mao's system, many such students "strengthened their own red identity" rather than deconstructing it. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Xi reportedly relied on family ties and party's recommendation to get it. Tsinghua is a top Beijing university and the same one Hu Jintao attended. The party selected his major, chemical engineering. He graduated from the school of humanities and social sciences but he never worked in the field. He later picked up a doctorate in Marxist theory and ideological education, making him one of the few Chinese leader educated in the arts rather than engineering. [Source: Edward Wong and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, January 23, 2011; Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian]

According to China. Org in 1998-2002 Xi studied Marxist theory and ideological education in an on-the-job postgraduate program at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tsinghua University and graduated with an LLD degree. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, Xi "has the autodidact’s habit of announcing his literary credentials. He often quotes from Chinese classics, and in an interview with the Russian press in 2014 he volunteered that he had read Krylov, Pushkin, Gogol, Lermontov, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, Nekrasov, Chernyshevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Sholokhov. When he visited France, he mentioned that he had read Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Saint-Simon, Fourier, Sartre, and twelve others.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

Xi’s education credentials are a sensitive but widely discussed topic. According to VOA News: “Xi left school when he was a middle school student during China’s Cultural Revolution and missed out on nearly a decade of education. When he was recommended to Tsinghua University at the end of the Cultural Revolution there was no national college entrance exam. Xi obtained a doctorate degree in law. Some critics have questioned Xi’s academic capability, suggesting his thesis may have been plagiarized or written by others. Xi has never commented on the controversy. [Source: VOA News, September 6, 2016]

Image Sources: Chinese government (China.org), Wikicommons; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; cave homes: beifen.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021