XI JINPING’S FAMILY AND FIRST MARRIAGE

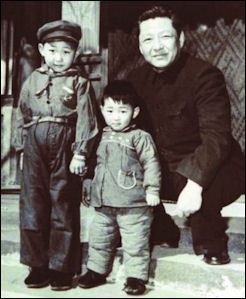

Xi Xinping with his father Xi Zhongxun and brother Xi Yuanping

Xi Jinping has a sister in Canada, a brother and sister in Hong Kong and a daughter that graduated from Harvard. His sister Xi Qiaoqiao and her husband Deng Jiagui own a major real estate company named Beijing Central People's Trust Real Estate Development Corporation Ltd. According to dissident Yue Jie they have the easiest method of doing business: Many local government officials offer the company the best land in order to improve their relationship with Xi Jinping.

During the Cultural Revolution the entire Xi family was punished. Xi's sister Qiaoqiao was also sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. The 5-yuan payment Qiaoqiao received for working in a corps with 500 other youths in Inner Mongolia made her feel rich, she recalled in an interview on the website of Beijing-based Tsinghua University. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012 ||||]

It is said President Xi cannot attend a family funeral, wedding or Spring Festival event without facing the absence of his oldest sister, Xi Heping. She committed suicide near the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1975. Australian journalist John Garnaut, author of book on Xi Jinping told The New Yorker, “It was suicide. Close associates have said to me, on the record, that after a decade of persecution she hanged herself from a shower rail.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

Bloomberg reported: Xi Jinping's father "Xi Zhongxun worked to imbue his children with the revolutionary spirit, according to accounts in state media that portray him as a principled and moral leader. Family members have recounted in interviews how he dressed them in patched hand-me-downs. He also made daughter Qiaoqiao turn down her top-choice middle school in Beijing, which offered her a slot despite her falling half a point short of the required grade, according to a memorial book about him. Instead, she attended another school under her mother’s family name, Qi, so classmates wouldn’t know her background. Qiaoqiao and her sister Anan also sometimes use their father’s family name, Xi. ||||

In October 2000, Xi Zhongxun’s family gathered on his 87th birthday for a photograph at a state guest house in Shenzhen, two years before the patriarch’s death. In the photo, Xi Zhongxun, dressed in a red sweater and holding a cane, is seated in an overstuffed armchair. To his left sits daughter Qi Qiaoqiao. On his right, a young grandson perches on doily-covered armrests next to the elder Xi’s wife, Qi Xin. Lined up behind are Qiaoqiao’s husband, Deng Jiagui; her brothers Xi Yuanping and Xi Jinping; and sister Qi Anan alongside her husband Wu Long. ||||

Not long after college, Xi married Ke Xiaoming (Ke Lingling), the elegant, well-connected and well-traveled daughter of China’s Ambassador to Britain. The young couple moved into a spacious apartment in a gated compound across from the state guesthouse but they split up after just three years. They fought “almost every day,” a friend from Xi’s university days, who lived across the hall, told the The New Yorker. He said that the couple divorced when Ke decided to move to England and Xi stayed behind. ^^^

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PENG LIYUAN: XI XINPING'S WIFE AND CHINA’S GLAMOROUS FIRST LADY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S EARLY LIFE, CHARACTER AND CAVE HOME YEARS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future” by Chun Han Wong Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China” (English Version) by the Chinese government Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018" by Alfred L. Chan Amazon.com; “CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Xi: A Study in Power: A Study in Power” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Snake Oil: How Xi Jinping Shut Down the World” by Michael P Senger Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping” by Willy Lam Amazon.com; “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” by François Bougon Amazon.com

Xi Jinping's Father Xi Zhongxun

Xi Jinping's father Xi Zhongxun was a powerful and long-time Communist. A Long March hero banished during the Cultural Revolution, Xi Zhongxun emerged as a reformer in the Deng Xiaoping era and was the architect of China’s Special Economic Zones that were integral in kick starting the Chinese economy under Deng. Xi Zhongxun, was a founder of the communist guerilla movement, a close associate of Deng Xiaoping and deputy prime minister from 1959 to 1962. He joined the party while in jail at age 14 for trying to poison his "reactionary" schoolteacher. Later he became one of the more liberal party leaders and was purged several times under Mao. In 1963, he was banished following an internal power struggle.

Elizabeth Economy of the Council on Foreign Relations wrote: “In 1962, Xi Zhongxun was accused of leading an anti-party group for supporting the Biography of Liu Zhidan. Hence when Jinping was 10, his father was purged by Mao from all leadership positions and sent to work in a factory. Things became worse a few years later as his father was jailed during the Cultural Revolution. Mao died in 1976 and the Cultural Revolution came to an end. Jinping’s father was reinstated and became party secretary of Guangdong. [Source: Elizabeth Economy, Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog, Forbes, October ct 15, 2014]

young Xi Jinping with his family in 1976 Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Xi Zhongxun was genuinely revered as an aide to Mao Tse-tung in setting up the Communist Party's base in Shaanxi province during the 1940s. Purged in the 1960s during the party rift that preceded the Cultural Revolution, he was later rehabilitated and became instrumental in opening the southern province of Guangdong to a market economy. In his later years, however, he fell out again with the party leadership, having supported liberal Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang. He is widely believed to have disapproved of the crackdown on student demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in 1989. After 1989, Xi Zhongxun was cast aside. Until the time of his death, he rarely appeared at public events. Much about Xi Zhongxun remains sensitive for the Communist Party. The second volume of his official biography was completed in 2009 but held up by censors. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 15, 2013]

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The seeds of Xi's resolve and ruling style are in his upbringing. Xi Zhongxun lived through hellish periods of internal party factionalism. He was purged multiple times — removed from power, incarcerated, even threatened with being buried alive — for his association with individuals and “gangs” who were deemed disloyal. Some of his mentors and associates committed suicide. Yet he remained devoted, even proud of his suffering at the party’s hands. “It’s hard to think of someone who’d more fanatically put party interests above his own interest,” said Joseph Torigian, a professor of history and politics at American University who is writing a biography of Xi Zhongxun. “A lot of that generation took pride in how much they were able to suffer without losing faith in the party. They often wrote about it as a sort of forging process.” At home, Xi Zhongxun — who worked at a tractor factory when he was purged but later became vice premier — was a “brutal disciplinarian” who struggled with depression, Torigian said, according to memoirs, unpublished diaries and interviews with friends of the family. When Xi Jinping was a child, he saw his father sometimes crying, screaming and hitting people, sitting in a room with all the lights off, and lashing out at his wife. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Xi Zhongxun's Life as Revolutionary

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, Xi Zhongxun had been fomenting revolution since the age of fourteen, when he and his classmates tried to poison a teacher whom they considered a counterrevolutionary. He was sent to jail, where he joined the Communist Party, and eventually he became a high-ranking commander, which plunged him into the Party’s internal feuds. In 1935, a rival faction accused Xi of disloyalty and ordered him to be buried alive, but Mao defused the crisis. At a Party meeting in February, 1952, Mao stated that the “suppression of counterrevolutionaries” required, on average, the execution of one person for every one thousand to two thousand citizens. Xi Zhongxun endorsed “severe suppression and punishment,” but in his area “killing was relatively lower,” according to his official biography. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

Xi Zhongxun was driven from power in 1962, when Mao accused him of seeking to subvert the party. After the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, Xi Zhongxun was paraded and persecuted by Red Guards, and his family was driven deeper into the political wilderness. Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “In 1962, his father was accused of supporting a novel that Mao opposed, and was sent to work in a factory; his mother, Qi Xin, was assigned to hard labor on a farm. In January, 1967, after Mao encouraged students to target “class enemies,” a group of young people dragged Xi Zhongxun before a crowd. Among other charges, he was accused of having gazed at West Berlin through binoculars during a visit to East Germany years earlier. He was detained in a military garrison, where he passed the years by walking in circles, he said later—ten thousand laps, and then ten thousand walking backward. ^^^

“Xi Jinping grew up with his father’s stories. “He talked about how he joined the revolution, and he’d say, ‘You will certainly make revolution in the future,’ ” Xi recalled in a 2004 interview with the Xi’an Evening News, a state-run paper. “He’d explain what revolution is. We heard so much of this that our ears got calluses.” In six decades of politics, his father had seen or deployed every tactic. At dinner with the elder Xi in 1980, David Lampton, a China specialist at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins, marvelled that he could toast dozens of guests, over glasses of Maotai, with no visible effects. “It became apparent that he was drinking water,” Lampton said. ^^^

Xi Jinping with his father and family in 1960

Xi Jinping’s Father After His Rehabilitation in 1974

Xi Zhongxun’s fortunes improved when Deng Xiaoping won the power struggle set off by Mao's death in 1976. Xi Zhongxun was appointed governor of Guangdong province in southern China which spearheaded the market-led economic policies launched by Deng at the end of 1978. Xi implemented the first Special Economic Zone (SEZ), persuading Deng to pioneer China’s experiment with open markets in Shenzhen, which grew from a fishing village across the border from Hong Kong into a manufacturing hub housing millions of migrant workers. Among his proteges was Hu Jintao. [Source: Fenby. Bloomberg]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “In 1974, Xi Zhongxun was rehabilitated, after sixteen years of persecution. When the family reunited, he could not recognize his grown sons. His faith never wavered. In November, 1976, he wrote to Hua Guofeng, the head of the Party, asking for reassignment, in order to “devote the rest of my life to the Party and strive to do more for the people.” He signed it, “Xi Zhongxun, a Follower of Chairman Mao and a Party Member Who Has Not Regained Admission to Regular Party Activities.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

Starting in 1978, Xi Zhongxun served in “Guangdong, home to China’s experiments with the free market, and the elder Xi had become a zealous believer in economic reform as the answer to poverty. It was a risky position: at a Politburo meeting in 1987, the Old Guard attacked the liberal standard-bearer, Hu Yaobang. Xi’s father was the only senior official who spoke in his defense. “What are you guys doing here? Don’t repeat what Mao did to us,” he said, according to Richard Baum’s 1994 chronicle of élite politics, “Burying Mao.” But Xi lost and was stripped of power for the last time. He was allowed to live in comfortable obscurity until his death, in 2002, and is remembered fondly as “a man of principle, not of strategy.”“ ^^^

Xi Zhongxun, the Liberal

In an article entitled "Learn from Xi Zhongxun, hope that Xi Jinping can honor his father's spirit with what he does", Colonel Xin Ziling, a former official at the China National Defense University, cited three examples of elder Xi’s liberal-mindedness.[Source: Ching Cheong, The Straits Times, December 10, 2010]

1) Ching Cheong wrote in The Straits Times: “Soon after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seized power in 1949, Mao Zedong sent out an order for "reactionary enemies" to be eliminated, setting a minimum quota of one in 1,000. Xi, who was party boss in the north-west region in the 1950s, persuaded Mao to let him lower the quota for his region to one in 2,000, thereby sparing many lives.”

2) “In the years immediately following the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), which had nearly bankrupted the Chinese economy, desperate and destitute Chinese tried to steal across the border from southern Guangdong province into the thriving British colony of Hong Kong. It was estimated that 120,000 attempts were made within a five-month period in 1979, although only 30,000 were successful. Chinese border guards at the time were under orders from Beijing to arrest or shoot anyone attempting to escape. Xi, by then party boss of Guangdong, realized that neither bullets nor wire fences would deter people in search of a better life. What was needed to make them stay was development that could improve their livelihoods. At a meeting in Beijing, he convinced Deng to let him set up an economic zone. Thus, the Shenzhen special economic zone, set up in 1980, was born out of necessity under Xi's watch.”

3) “In 1987, when conservative party elders forced reformist CCP chief Hu Yaobang to resign, Xi was the only one who protested strongly at an informal tea gathering of the elders, saying the sacking was illegal.” Edward Wong and Jonathan Ansfield wrote in the New York Times, “Behind closed party doors, he supported the liberal-leaning leader Hu Yaobang and condemned the military crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protesters in 1989.”

Jonathan Fenby wrote in The Guardian, “In old age, the party veteran showed his independence of mind by arguing for wider reform and criticizing the repression of the protests in 1989 that culminated in the bloodbath on Beijing on 4 June. This free speaking did not stop his son's rise.”

Influence of Xi Jinping’s Father on Xi Jinping

Xi with his daughter Xi Mingze

Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker: Oddly, it also makes Xi the kind of man who has something in common with our President. Both men have been shaped by their fathers’ experiences—and their experiences with their fathers—though in very different ways. Obama devoted a book to a father he only knew for a month; Xi has rarely discussed his own—a man who made his name as a revolutionary father of China, fell from political grace, recovered, and went on to implement some of China’s most liberal economic policies. [Source: Jiayang Fan, The New Yorker, February 23, 2012]

Xi senior, from whom Xi must have inherited some of his survival instincts, passed away in 2004. A Washington Post article about Xi’s past mentions the story of his father meeting his family after years of solitary confinement and being unable to recognize his children. The moment prompted him to recite lines from a Tang poem known to all Chinese grade-schoolers:

Coming back to my home village after years of absence,

My brows have grayed though my accent remains unchanged.

Children who meet me don’t recognize me.

Laughingly, they ask about the village where I have come from.

Honoring Xi Jinping’s Father

A statue of Xi Jinping’s father and a museum dedicated to him sit in Fuping in Shaanxi Province.Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “A statue of the father of the nation's leader — 60 tons of granite — serves as the centerpiece of a square flanked by cypress trees. People approach along a long walkway and bow in the direction of his seated figure. Many carry oversized sprays of flowers. A museum dedicated to his life is at the other end of the walkway. Older women with straw hats and baskets squat on the grass, picking out weeds by hand to keep the grounds immaculate. The optics look straight out of North Korea, but this is in fact China. The statue and park in the city of Fuping are devoted to Xi Zhongxun, the late father of Xi Jinping...Next to the statue is a photo exhibit titled "A Noble Spirit Will Never Perish" that jumps from the 1950s to 1978, conveniently omitting Xi's persecution by Mao during the Cultural Revolution. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 15, 2013]

Xi Zhongxun in 1949

“The late Xi, an early communist leader, is enjoying a postmortem revival. In honor of the 100th anniversary of his birth, the Chinese post office issued two commemorative stamps, one a portrait and the other showing him in his Red Army uniform. Commemorative ceremonies were held around the country, including one in Beijing's Great Hall of the People, presided over by his son. Many of the tributes are centered in Fuping, the city of his birth and burial in Shaanxi province. The statue here was constructed in 2005, at a time his son was serving as party secretary in Zhejiang province.

“The local government is now raising money for what it says will be a $3-billion theme park spread over 2,700 acres. The park is to include entertainment, cultural and exhibition centers and a spa, according to a notice published in April by the municipal government. "The new park will have a larger statue of Xi Zhongxun," said Yan Xiaoqiang, a tourism official in Fuping. Fuping's interest in Xi Zhongxun was inspired by the boom in what is called "red tourism," he said. "Chinese are paying more attention to their own history and commemorating the revolutionary heroes who helped to establish the country," said Yan. "It is about Xi Zhongxun's contributions to Chinese history, not about his son being president."

Nevertheless, the coincidence cannot be so easily dismissed, political experts say. "When the son is promoted so is the father," said Li Datong, a former editor at the Communist Youth Daily newspaper whose family was acquainted with Xi's. In no way is the celebration of the elder Xi made out of whole cloth, like in North Korea.

“After his death in 2002, Xi Zhongxun’s ashes were buried at Babaoshan, the official cemetery of the Communist Party, but moved to Fuping in 2005, the year the statue was erected. Under Chinese traditions of feng shui, tombs of the ancestors are believed to greatly influence the fortunes of the living. The grave of the leader's father has brought increasing numbers of tourists to Fuping, a backwater even by the standards of rural Shaanxi province. "There has definitely been an increase in visits since Xi Zhongxun's son became leader," said Yan, the Fuping tourism official. "During the national holidays, it is so crowded there isn't even a place to stand."

“One person who hasn't visited much is Xi Jinping. Aside from the ceremony in October 2013 the president has distanced himself from the tributes. Political analysts say Xi is keen to avoid the perception that he is a "princeling." "Whenever Xi goes to visit the family tomb, he is very low-key. He does not want to be accused of creating a cult of personality," said Zhang Lifan, a Beijing historian. "It is a huge taboo for Chinese leaders to expand family tombs or renovate childhood homes," said Li. "I think this is all local officials trying to ingratiate themselves. That's how China works."

Peng Liyuan, Xi Jinping’s Wife

Xi’s wife, Peng Liyuan For many years, Xi Jinping’s wife, Peng Liyuan, a celebrated folk singer, was better known than him. Jane Perlez wrote in the New York Times: Peng Liyuan, China’s new first lady, is glamorous, fashionable and one of her nation’s best-known singers, a startling contrast to her dour-looking predecessors. As she accompanies her husband on his trips abroad she appears ready to carve out a new role for herself. At a time when China’s Foreign Ministry is struggling to improve China’s international image, Ms. Peng, who has dazzled audiences at home and abroad with her bravura soprano voice, comes as a welcome gift. “Because of her performer’s background and presence, I think she will definitely add points for her husband,” said Tian Yimiao, an associate professor at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. “It could make her into a diplomatic idol.” Although Mr. Xi may not like the comparison, some see her as a figure akin to Raisa Gorbachev, the wife of Mikhail S. Gorbachev, who helped humanize the Soviet leader as the Soviet Union fell apart. Mr. Xi has singled out Mr. Gorbachev as a man who let down the cause of Communism. Others see her as roughly equivalent to Michelle Obama: modern, outgoing, intrigued by fashion. [Source: Jane Perlez, New York Times, March 24, 2013]

Xi Mingze, grown up

Gillian Wong of Associated Press wrote: “The country has no recent precedent for the role of first lady and faces a tricky balance at home. The leadership wants Peng to show the human side of the new No. 1 leader, Xi Jinping, while not exposing too many perks of the elite. And it must balance popular support for the first couple with an acute wariness of personality cults that could skew the consensus rule among the Chinese Communist Party's top leaders. [Source: Gillian Wong, Associated Press, March 28, 2013]

Like her husband, Peng is steeped in Communist tradition. Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press reported: “While Xi's father was a leading revolutionary and former vice-premier, making his son a member of the "red aristocracy," Peng comes from relatively humble origins and joined the People's Liberation Army when she was 18. While sometimes described as a folk singer, Peng holds the rank of PLA major general and is best known for her stirring renditions of patriotic odes, often while wearing full dress uniform. Although her rank is largely honorary, her military status could lead to awkward questions, said University of Nottingham's Tsang. "Sooner or later, someone is going to ask whether that's completely normal, even if she doesn't have any real military or political ambitions," Tsang said. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, AP, March 24, 2013]

See Separate Article PENG LIYUAN: XI XINPING'S WIFE AND CHINA’S GLAMOROUS FIRST LADY factsanddetails.com

Jinping’s Daughter at Harvard

Xi Jinping ’s daughter, Xi Mingze, has avoided the spotlight. She graduated from Harvard in 2014 and returned to China. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “On a sunny morning” in May 2014 she “crossed the podium at Adams House, the dorm that housed Franklin Roosevelt and Henry Kissinger. She had studied psychology and English and lived under an assumed name, her identity known only to a limited number of faculty and close friends—“less than ten,” according to Kenji Minemura, a correspondent for the Asahi Shimbun, who attended the commencement and wrote about Xi’s experience in America. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

“Xi Mingze was largely protected from press attention, much like the college-age children of other heads of state. (legal proceedings excepted). Some offspring of other Chinese leaders have courted attention abroad, however. Before the former Politburo member Bo Xilai was imprisoned for corruption and his wife, Gu Kailai, jailed for murder, their son, Bo Guagua, invited Jackie Chan to Oxford, and sang with him onstage; he drove a Porsche during his time as a graduate student at Harvard. Xi, on the other hand, led a “frugal life” in Cambridge, according to Minemura. “She studied all the time,” he told me recently.”

“At twenty-two, Xi Mingze has now returned to China; though she makes few public appearances, she joined her parents on a recent trip to Yan’an, the rural region where her father was sent to work during the Cultural Revolution, when he was a teen-ager.”

Xi Jinping’s Family’s Wealth

Xi with wife and daughter and parents

Xi Jinping warned officials on a 2004 anti-graft conference call: “Rein in your spouses, children, relatives, friends and staff, and vow not to use power for personal gain.” In June 2012, Bloomberg News reported: “As Xi climbed the Communist Party ranks, his extended family expanded their business interests to include minerals, real estate and mobile-phone equipment, according to public documents compiled by Bloomberg. Those interests include investments in companies with total assets of $376 million; an 18 percent indirect stake in a rare- earths company with $1.73 billion in assets; and a $20.2 million holding in a publicly traded technology company. The figures don’t account for liabilities and thus don’t reflect the family’s net worth. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

No assets were traced to Xi, who turns 59 this month; his wife Peng Liyuan or their daughter, the documents show. There is no indication Xi intervened to advance his relatives’ business transactions, or of any wrongdoing by Xi or his extended family.While the investments are obscured from public view by multiple holding companies, government restrictions on access to company documents and in some cases online censorship, they are identified in thousands of pages of regulatory filings.

The trail also leads to a hillside villa overlooking the South China Sea in Hong Kong, with an estimated value of $31.5 million. The doorbell ringer dangles from its wires, and neighbors say the house has been empty for years. The family owns at least six other Hong Kong properties with a combined estimated value of $24.1 million.

For months after the story about the family riches of Xi was run Bloomberg’s website was unavailable in China.

Holdings of Xi Jinping’s Family

Bloomberg News reported: “Most of the extended Xi family’s assets traced by Bloomberg were owned by Xi’s older sister,Qi Qiaoqiao, 63; her husband Deng Jiagui, 61; and Qi’s daughter Zhang Yannan, 33, according to public records compiled by Bloomberg. Deng held an indirect 18 percent stake as recently as June 2012 in Jiangxi Rare Earth & Rare Metals Tungsten Group Corp. Prices of the minerals used in wind turbines and U.S. smart bombs have surged as China tightened supply. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

Qi and Deng’s share of the assets of Shenzhen Yuanwei Investment Co., a real-estate and diversified holding company, totaled 1.83 billion yuan ($288 million), a December 2011 filing shows. Other companies in the Yuanwei group wholly owned by the couple have combined assets of at least 539.3 million yuan ($84.8 million). A 3.17 million-yuan investment by Zhang in Beijing-based Hiconics Drive Technology Co. (300048) has increased 40-fold since 2009 to 128.4 million yuan ($20.2 million) as of yesterday’s close in Shenzhen.

Xi Jinping with his father and brother and sisters

Deng, reached on his mobile phone, said he was retired. When asked about his wife, Zhang and their businesses across the country, he said: “It’s not convenient for me to talk to you about this too much.” Attempts to reach Qi and Zhang directly or through their companies by phone and fax, as well as visits to addresses found on filings, were unsuccessful.

Another brother-in-law of Xi Jinping, Wu Long, ran a telecommunications company named New Postcom Equipment Co. The company was owned as of May 28 by relatives three times removed from Wu — the family of his younger brother’s wife, according to public documents and an interview with one of the company’s registered owners. New Postcom won hundreds of millions of yuan in contracts from state-owned China Mobile Communications Corp., the world’s biggest phone company by number of users, according to analysts at BDA China Ltd., a Beijing-based consulting firm that advises technology companies.

Bloomberg’s accounting included only assets, property and shareholdings in which there was documentation of ownership by a family member and an amount could be clearly assigned. Assets were traced using public and business records, interviews with acquaintances and Hong Kong and Chinese identity-card numbers. In cases where family members use different names in mainland China and in Hong Kong, Bloomberg verified identities by speaking to people who had met them and through multiple company documents that show the same names together and shared addresses.

Xi Jinping’s Sister and her Family’s Wealth

Bloomberg News reported: “After Mao’s death in 1976, the family was rehabilitated and Xi’s sister Qiaoqiao pursued a career with the military and as a director with the People’s Armed Police. She resigned to care for her father, who had retired in 1990, Qiaoqiao said in the Tsinghua interview. Property Purchase A year later, she bought an apartment in what was then the British colony of Hong Kong for HK$3 million ($387,000) — at the time, equivalent to almost 900 times the average Chinese worker’s annual salary. She still owns the property, in the Pacific Palisades complex in Braemar Hill on Hong Kong island, land registry records show. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

By 1997, Qi and Deng had recorded an investment of 15.3 million yuan in a company that later became Shenzhen Yuanwei Industries Co., a holding group, documents show. The assets of that company aren’t publicly available. However, one of its subsidiaries, Shenzhen Yuanwei Investment, had assets of 1.85 billion yuan ($291 million) at the end of 2010. It is 99 percent owned by the couple, according to a December 2011 filing by a securities firm. It was after her father’s death in 2002 that Qi said she decided to go into business, according to the Tsinghua interview. She graduated from Tsinghua’s executive master’s degree in business administration program in 2006 and founded its folk-drumming team. It plays in the style of Shaanxi province, where Xi Zhongxun was born.

The names Qi Qiaoqiao, Deng Jiagui or Zhang Yannan appear on the filings of at least 25 companies over the past two decades in China and Hong Kong, either as shareholders, directors or legal representatives — a term that denotes the person responsible for a company, such as its chairman. In some filings, Qi used the name Chai Lin-hing. The alias was linked to her because of biographical details in a Chinese company document that match those in two published interviews with Qi Qiaoqiao. Chai Lin-hing has owned multiple companies and a property in Hong Kong with Deng Jiagui. In 2005, Zhang Yannan started appearing on Hong Kong documents, when Qi and Deng transferred to her 99.98 percent of a property-holding company that owns one apartment, a unit in the Regent on the Park development with an estimated value of HK$54 million ($6.96 million).

Land registry records show Zhang paid HK$150 million ($19 million) in 2009 for the villa on Belleview Drive in Repulse Bay, one of Hong Kong’s most exclusive neighborhoods. Property prices have since jumped about 60 percent in the area. Her Hong Kong identity card number, written on one of the sale documents, matches that found on the company she owns with her mother and Deng Jiagui, Special Joy Investments Ltd. All three people share the same Hong Kong address in a May 12 filing. Zhang owns four other luxury units in the Convention Plaza Apartments residential tower with panoramic harbor views adjoining the Grand Hyatt hotel.

In mainland China, Qi and Deng’s marquee project is a luxury housing complex called Guanyuan near Beijing’s financial district, boasting manicured gardens and a gray-brick exterior reminiscent of the city’s historic courtyard homes. Financial details on the developer aren’t available because of restrictions on company searches in Beijing. To finance the development, the couple borrowed from friends and banks, and aimed to attract officials and executives at state-owned companies, they told V Marketing China magazine in a 2006 interview. Property prices in the capital rose 79 percent in the following four years, government data show.

The site’s developer — 70 percent owned by Qi and Deng’s Yuanwei Investment — acquired more than 10,000 square meters of land for 95.6 million yuan in 2004 to build Guanyuan, according to the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Land and Resources. A 189-square-meter (2,034-square-foot) three-bedroom apartment in Guanyuan listed online in June for 15 million yuan. One square meter sells for 79,365 yuan — more than double China’s annual per capita gross domestic product.

Xi Xinping with his cave home comrades in 1975

Xi Jinping’s Sister’ Family, Rare Earths and Electronic Devices

Bloomberg News reported: “One of Deng’s well-timed acquisitions was in a state-owned company with investments in rare-earth metals. Deng’s Shanghai Wangchao Investment Co. bought a 30 percent stake in Jiangxi Rare Earth for 450 million yuan ($71 million) in 2008, according to a bond prospectus. Deng owned 60 percent of Shanghai Wangchao. A copy of Deng’s Chinese identity card found in company registry documents matches one found in filings of a Yuanwei subsidiary. Yuanwei group-linked executives held the posts of vice chairman and chief financial officer in Jiangxi Rare Earth, the filings show. The investment came as China, which has a near monopoly on production of the metals, was tightening control over production and exports, a policy that led to a more than fourfold surge in prices for some rare earths in 2011. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

Qi Qiaoqiao’s daughter Zhang made her 3.17 million-yuan investment in Hiconics in the three years before the Beijing- based manufacturer of electronic devices sold shares to the public in 2010. Hiconics founder Liu Jincheng was in the same executive MBA class as Qi Qiaoqiao, according to his profile on Tsinghua’s website.

The business interests of Qi and Deng may be more extensive still: The names appear as the legal representative of at least 11 companies in Beijing and Shenzhen, cities where restrictions on access to filings make it difficult to determine ownership of companies or asset values. For example, Deng was the legal representative of a Beijing-based company that bought a 0.8 percent stake in one of China’s biggest developers, Dalian Wanda Commercial Properties Co., for 30 million yuan in a 2009 private placement. Dalian Wanda Commercial had sales of 95.3 billion yuan ($15 billion) last year. Deng also served as legal representative of a company that won a government contract to help build a 1 billion-yuan ($157 million) bridge in central China’s Hubei province, according to an official website and corporate records.

Xi Jinping’s Brother-in-Law and New Postcom

Bloomberg News reported: “In the case of Xi Jinping’s brother-in-law, Wu Long, he’s identified as chairman of New Postcom in two reports on the website of the Guangzhou Development District, one in 2009 and the other a year later. New Postcom doesn’t provide a list of management on its website. Searches in Chinese on Baidu Inc.’s search engine using the name “Wu Long” and “New Postcom” trigger a warning, also in Chinese: “The search results may not be in accordance with relevant laws, regulations and policies, and cannot display.” [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

New Postcom is owned by two people named Geng Minhua and Hua Feng, filings show. Their address in the company documents leads to the ninth floor of a decades-old concrete tower in Beijing where Geng’s elderly mother lives. Tacked to the wall of her living room was the mobile-phone number of her daughter.

When contacted by phone June 6, Geng confirmed she owned New Postcom with her son Hua Feng — and that her daughter was married to Wu Ming, Wu Long’s younger brother. Geng said Wu Long headed the company and she wasn’t involved in the management.

New Postcom identified two different people — Hong Ying and Ma Wenbiao — as its owners in a six-page, June 27 statement and said the head of the company was a person named Liu Ran. The company didn’t respond to repeated requests to explain the discrepancies. Wu Long and his wife, Qi Anan, couldn’t be reached for comment.

New Postcom was an upstart company that benefited from state contracts. It specialized in the government-mandated home- grown 3G mobile-phone standard deployed by China Mobile. In 2007, it won a share of a tender to supply handsets, beating out more established competitors such as Motorola Inc., according to BDA China. “They were an unknown that suddenly appeared,” said Duncan Clark, chairman of BDA. “People were expecting Motorola to get a big part of that device contract, and then a no-name company just appeared at the top of the list.” In 2007, the domestic mobile standard was still being developed, and many of the bigger players were sitting on the sidelines, allowing New Postcom a bigger share of the market, the company said in the statement.

Xi Jinping’s Younger Brother and His Energy Deals

Xi Jinping’s younger brother, Xi Yuanping, is the founding chairman of an energy advisory body called the International Energy Conservation Environmental Protection Association. He doesn’t play an active role in the organization, according to an employee who declined to be identified. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

One of Xi’s nieces has a higher profile. Hiu Ng, the daughter of Qi Anan and Wu Long, and her husband Daniel Foa, 35, last year were listed as speakers at a networking symposium in the Maldives on sustainable tourism with the likes of the U.K. billionaire Richard Branson and the actress Daryl Hannah.

Ng recently began working with Hudson Clean Energy Partners LP, which manages a fund of more than $1 billion in the U.S., to help identify investments in China. Details about the couple were removed from Internet profiles after Bloomberg reporters contacted them. Foa said by phone he couldn’t comment about FairKlima Capital, a clean- energy fund they set up in 2007. Ng didn’t respond to e-mails asking for an interview. The two are no longer mentioned on the FairKlima website. A June 3 cache of the “Contact Us” webpage includes short biographies of Ng and Foa under the headline ‘senior Management Team.”

A reference on Ng’s LinkedIn profile that said on June 8 that she worked at New Postcom has since been removed, along with her designation as “Vice Chair Hudson Clean Energy Partners China.” Neil Auerbach, the Teaneck, New Jersey-based private-equity firm’s founder, said he was working with Ng because of her longstanding passion for sustainability.

Xi Jinping’s Brother-in-Law Implicated in the Panama Papers Scandal

Xi Jinping’s family was implicated in the Panama Papers Scandal. AFP reported: The families of some of China’s top communist brass — including President Xi Jinping — used offshore tax havens to conceal their fortunes, a treasure trove of leaked documents has revealed.” Those implicated included “Xi’s brother-in-law Deng Jiagui, who in 2009 — when his famous relation was a member of the Politburo Standing Committee but not yet president — set up two British Virgin Islands companies.Xi has been dogged by foreign media reports of great family wealth. The claims are ignored by mainstream Chinese outlets, and their publication on the Internet in China is suppressed. Since becoming president that same year, Xi has staked his reputation on pushing for transparency by initiating a vast anti-graft campaign to clean the party’s ranks of corruption and to reassert his authority. [Source: AFP, April 4, 2016]

Juliette Garside and David Pegg wrote in The Guardian: “Deng Jiagui was a shareholder in two BVI companies, Wealth Ming International and Best Effect Enterprises. Deng appeared on the shareholder registers of both companies in September 2009. They both existed for roughly 18 months before being closed in April 2011 and October 2010 respectively.The previous leak of offshore documents revealed Deng owned a 50 percent stake in the BVI-incorporated Excellence Effort Property Development. Ownership of the remainder of the company has been traced back to two Chinese property tycoons. [Source: Juliette Garside and David Pegg, The Guardian, April 6, 2016 =/=]

“Deng is married to Xi’s older sister, and together they built a fortune through investments in property and natural resources. In 2012, they were reported to hold stakes in companies with total assets of $376 million, and an indirect 18 percent share in a minerals company worth $2 billion. Since Xi became president, they have pulled out of many of their investments. Thanks to his close connection to the centre of Chinese power, Deng qualifies as a PEP. Banks, registered agents and professionals such as lawyers are obliged to carry out detailed checks on the source of funds when managing money for politicians, public officials, their families and close associates. Deng was the named shareholder and had given the firm his Hong Kong identity papers. But Mossack Fonseca’s files did not list him as a PEP, raising questions about whether detailed checks were made on what his offshore vehicles were used for. Deng did not respond to requests for comment.” =/=

Image Sources: Chinese government (China.org), Wikicommons; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org ; Twitter; Xi on bicycle with daughter; Evan Osnos: older Xi Mingze

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021