XI JINPING AND MAOISM

Cover of Time in March 2016

Xi Jinping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or CPC) in November 2012. He became Chinese president in March 2013 and over time claimed other titles to become China’s unquestioned leader to such a degree he has been called a new Mao and a new Emperor.

Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “Mr. Xi has shown no inclination to try to take China back to Mao’s era of a command economy and fervent Communist campaigns. But he has repeatedly said that the party would mortally damage its authority if it abandoned Mao’s legacy. “Imagine if Comrade Mao Zedong had been totally repudiated. Would our party be able to withstand that?” Mr. Xi said in a speech in early 2013, according to a collection of documents published last year. “Would our country’s socialist system be able to withstand it? They wouldn’t, and when they wouldn’t, it would be great turmoil under the heavens. Critics have warned that Mr. Xi’s demands for unblinking obedience risk rekindling some of the ideological mania of Mao’s time. This week, the president of Nankai University in the northern city of Tianjin warned against reports in the party news media that have depicted universities as threatened by an infiltration of Western liberal ideas and values. “We cannot re-enact this history of ‘leftist’ errors against intellectuals,” said the university’s president, Gong Ke.” [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, February 13, 2015]

Xi Jinping announced “three self-confidences”—“1) Be confident in the path, 2) be confident in the theory, 3) be confident in the system”—in a speech to new members of the Central Committee. Cheng Xiaonong, a U.S.-based scholar of the Communist Party, told the Epoch Times that the speech show that Xi Jinping does not seek to deny the Mao era. “If so, he’s more conservative than Deng Xiaoping, and it’s understandable why the red song is there. It helps the regime establish some legitimacy, affirming the achievements of Mao in the Cultural Revolution.”

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: XI JINPING factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S EARLY LIFE, CHARACTER AND CAVE HOME YEARS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FAMILY, HARVARD EDUCATED DAUGHTER AND FAMILY WEALTH factsanddetails.com; PENG LIYUAN: XI XINPING'S WIFE AND CHINA’S GLAMOROUS FIRST LADY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S POLITICAL CAREER AND RISE IN THE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BEFORE HE BECAME THE LEADER OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BECOMES THE LEADER OF CHINA: HIS INNER CIRCLE, STYLE AND DIRECTIONS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S AUTHORITARIANISM AND TIGHT GRIP ON POWER factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S STYLE, LEADERSHIP AND PERSONALITY CULT factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S DOMESTIC POLICY: CHINESE DREAM, ECONOMICS AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S ANTI-CORRUPTION DRIVE factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, HUMAN RIGHTS AND OPPOSITION TO WESTERN IDEAS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, THE MEDIA AND THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF HIM factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com; LI KEQIANG factsanddetails.com; CHINA'S POLITBURO STANDING COMMITTEE MEMBERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future” by Chun Han Wong Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China” (English Version) by the Chinese government Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018" by Alfred L. Chan Amazon.com; “CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Xi: A Study in Power: A Study in Power” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Snake Oil: How Xi Jinping Shut Down the World” by Michael P Senger Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping” by Willy Lam Amazon.com; “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” by François Bougon Amazon.com

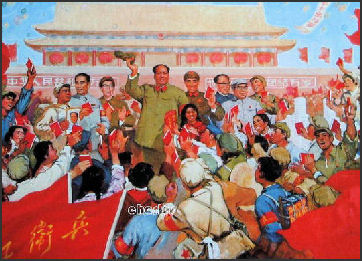

Xi Jinping: the New Mao?

Hu Jia, one of the most outspoken political dissidents still living in mainland China, told the The Guardian that similarities between Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping are so strong that the Little Red Book could serve as a good guide to contemporary Chinese politics. “We call Xi ‘Mao Jinping’ or ‘Xi Zedong,’” Hu said. "As a Chinese person, I can tell you that Xi Jinping is a big Maoist, both in ideological terms and in how he tries to control Chinese society,” In 2013, during commemorations of 120 years since Mao’s birth, Xi Jinping vowed to “hold high the banner of Mao Zedong Thought forever”. “Mao is a great figure who changed the face of the nation and led the Chinese people to a new destiny,” he said. [Source: Tom Phillips, The Guardian, November 26, 2015]

Barbara Demick wrote in The Atlantic: “Although Xi is widely considered the most authoritarian leader since Mao, and is often referred to in the foreign press as “the new Mao,” he is no fan of the Cultural Revolution. As a teenager, he was one of the 16 million Chinese youths exiled to the countryside, where he lived in a cave while toiling away. His father, Xi Zhongxun, a former comrade of Mao’s, was purged repeatedly. And yet Xi has anointed himself the custodian of Mao’s legacy. He has twice paid homage to Mao’s mausoleum in Tiananmen Square, bowing reverently to the statue of the Great Helmsman. Tolerance for free expression has shrunk under Xi. A few officials have been fired for criticizing Mao. In recent years, teachers have been disciplined for what is called “improper speech,” which encompasses disrespecting Mao’s legacy. Some textbooks gloss over the decade of chaos, a retreat from the admission of mass suffering in the 1981 resolution, which ushered in a period of relative openness compared with today. [Source: Barbara Demick, The Atlantic, November 16, 2020]

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Whereas Mao incited grass-roots movements and armed struggle, Xi's approach to power eschews mass mobilization. “You see this huge emphasis on order and discipline. That’s seemingly a very strong reaction against the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and Mao’s chaotic approach,” said Ryan Mitchell, a professor of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Under Mao, the legal system was “decimated,” he said. “Xi is instead trying to institutionalize things, including his own power.” [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Echoes of Mao Zedong's in Xi Jinping’s Leadership Style

Raymond Li wrote in the South China Morning Post, “Xi Jinping has turned to an austerity lesson given by Mao Zedong more than six decades ago to advance his campaign against party corruption. During a visit to Xibaipo — the People's Liberation Army's headquarters at the end of the civil war — Xi reminded party members of Mao's so-called six nos, which barred officials from things like hosting birthday parties and exchanging presents. Xi likened party members' efforts to meet the guidelines to a student going through rigid exams — they had failed to shape up. He said his campaign to rid the party of "formalism, bureaucratism and hedonism and extravagance" would help them make the grade. [Source: Raymond Li, South China Morning Post, July 15, 2013 ^^]

“The party secretary's visit to Hebei province was his latest effort to push his year-long "mass line" campaign, which is designed to bolster the party's ties to the people amid growing discontent over corruption. Unveiled in April, the campaign obliges officials from the county level or higher to "reflect on their own practices and correct any misbehaviour" in accordance with public sentiment. ^^

“The party secretary's visit to Hebei province was his latest effort to push his year-long "mass line" campaign, which is designed to bolster the party's ties to the people amid growing discontent over corruption. Unveiled in April, the campaign obliges officials from the county level or higher to "reflect on their own practices and correct any misbehaviour" in accordance with public sentiment. ^^

“The campaign's similarity to Mao's efforts has caused unease. But Sima Nan, a leftist and conservative scholar, said that Xi's mass line campaign was less about leaning to the left, than reaffirming a fundamental party doctrine for the party. Sima said that Xi's mass-line movement was of greater significance because it specifically targeted official corruption, which the public has blamed for widening the wealth gap and pushing rapid development at the expense of the environment. "I have my concerns that such a campaign could become another formality as with some other campaigns because the central authorities might not necessarily bring lower-level authorities on board," Sima said. "They have developed many sophisticated ways of pushing ahead with their own priorities without overtly upsetting higher authorities." ^^

“Xi's pilgrimage to Xibaipo followed similar visits by former party leaders such as Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Beijing-based political commentator Zhang Lifan said Xi's attempt to revive some of Mao's legacy underscored that the party was suffering from a lack of creativity. "It has no other choice but to delve into some of the old doctrines even though they have had little appeal, particularly among the older generations," he said, noting growing disappointment with Xi among those who hoped for change. "That's why we have seen his popularity go down."Zhang said the "mass line" campaign could do little to shake up the party as it lacked support from low-level authorities who would condemn it as another formality. He noted, however, that Xi could still use it as a political tool to purge undesired cadres and consolidate his power base.” ^^

Maoist and Pro-Bo-Xilai Demonstrations Against Xi Government

Reporting from Luoyang in Henan Province, Seiichiro Takeuchi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Groups of so-called Maoists disgruntled over Chinese President Xi Jinping’s current government have been intensifying their activities in the run-up to the 120th birthday in December of late leader Mao Zedong. Though the Xi administration has been trying to put tighter controls on the Maoists, it has found it difficult to deal with them, as it cannot completely rebuke Maoism, which comprises the ideas of the national hero. [Source: Seiichiro Takeuchi, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 11, 2013 \//]

“On May 27, about 100 people carrying portraits of Mao and the Chinese Communist Party flag gathered at a plaza in Luoyang, an underdeveloped inland city in Henan Province. The meeting was held under the pretext of opposing genetically modified foods. At the gathering, however, they read aloud a statement defending Bo Xilai, former secretary of the Chinese Communist Party’s Chongqing committee, as a victim of a political battle. Bo had copied Mao’s political style, but fell from power in a scandal last year. Some people at the gathering shouted a slogan denouncing former Premier Wen Jiabao as a traitor because Wen was considered to have spearheaded the attack on Bo and criticized Maoism. “The meeting aims to criticize the reform and opening-up policy,” said a 59-year-old participant who used to be a security guard. \//

Xi Zhongxun with Mao and other leaders and the Dalai Lama

“The meeting was organized by a group of farmers, retired workers and others, who were left out of economic development brought about by the reform and opening-up policy. They are called Maoists or leftists. They run the so-called Society of Red (Revolutionary) Songs, a nationwide organization that publishes online critiques of the reform and opening-up policy for widening the gap between rich and poor. The group also calls for the public to return to the state of affairs in Mao’s period, when everyone was equally poor. \//

“One Maoist, a 65-year-old former executive of a state-run company, said he had carried Mao’s portrait and protested against the CCP during anti-Japanese demonstrations in September. In its blog, the Maoist group called for the public to hold gatherings in more than 10 places around China, including Luoyang, Changsha in Hunan Province and Wuhan in Hubei Province. In Shanxi Province, another group of Maoist proponents also called for gatherings. It is apparent that Maoists are trying to attract frustrated people around the country. If public protests around China against the government’s land seizures and other acts are connected to Maoists, it will become a clear threat to the Xi administration. \//

“According to Maoist sources, however, most of the planned gatherings were obstructed by police. On May 24, Zhang Qinde, a Maoist opinion leader who planned a gathering in Beijing, was detained. Zhang was a former chief of the general department at the Central Political Study of the CCP.However, the Xi administration cannot reject Maoism itself, as the Chinese Constitution and CCP regulations regard it to be an important school of thought. \//

Echoes of Mao: Xi Plan to Send Artists to Live in Rural Communities

In December 2014, the South China Morning Post reported: “China is to send artists, filmmakers, and television staff to live among the masses in rural areas in order to “form a correct view of art”, state media said today. The move is the latest by the ruling Communist Party to echo the ideology of Mao Zedong's era, including the Cultural Revolution, during which intellectuals and others were “sent down” to work alongside peasants in the countryside. It comes weeks after President Xi Jinping told a group of artists not to chase popularity with “vulgar” works, but instead to promote socialism. State media compared his remarks with those made in a speech by Mao in the 1940s. [Source: South China Morning Post, December 1, 2014 ==]

“China’s media watchdog “will organise film and TV series production staff on a quarterly basis to go to grassroots communities, villages and mining sites to do field study and experience life”, the official Xinhua news agency reported, citing a statement by the State General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. Scriptwriters, directors, broadcasters and TV presenters will also be sent to work and live for at least 30 days “in ethnic minority and border areas, and areas that made major contributions to the country’s victory in the revolutionary war”, Xinhua added. The move “will be a boost in helping artists form a correct view of art and create more masterpieces”, Xinhua said, citing the media administration. Beijing imposes tight controls over art and culture, and ideological restrictions have tightened under Xi, with authorities censoring prominent dissident artist Ai Weiwei and other artists that it perceives as challenging its right to rule. ==

“Joseph Cheng, professor of political science at City University, described the move as a Mao-style “rectification campaign” aimed at silencing potential critics as Xi leads a far-reaching anti-graft sweep. “Xi Jinping is under considerable pressure, because his anti-corruption campaign certainly has hurt a lot of vested interests,” Cheng said. “This is again a time of pressure tactics on the intelligentsia and on the critics.” The new edict harks back to the era of Communist China’s founder, when popular art was little more than propaganda. However, Cheng said that whereas Mao’s Cultural Revolution was aimed at the entire intelligentsia, the current move was more targeted. “This campaign is a bit different in the sense that as long as you don’t challenge the authorities – as long as you keep quiet – you are safe to keep making money,” he said.” ==

In October 2014, “Xi told a group of artists that they should not become “slaves to the market”. The state-run China Daily likened his remarks to a well-known speech by Mao in 1942 during the Yanan rectification movement, which outlined his view that the arts should serve politics. “Art and culture cannot develop without political guidance,” the paper said, congratulating Xi for “emphasising the integration of ideology and artistic values”.

Xi Jinping Visits Yan’an, the Communist Party Mecca

Mao in Yan'an in 1946

In February 2015, as China prepared to celebrate the lunar New Year, Xi Jinping visited Yan’an, where some say the Maoist era began, and the village of Liangjiahe, where Xi spent his seven years during the Cultural Revolution. Yan’an was the rural stronghold from where Mao Zedong regrouped and masterminded the Communist revolution. Liangjiahe is where lived in cave dwellings during his late teens and early 20s when he, like millions of urban youths, was “sent down” to the countryside. The visit was largely seen as another demonstration of Xi’s public veneration of the Maoist past. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, February 13, 2015]

Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “On the cusp of each Lunar New Year, Chinese Communist Party leaders make heavily publicized trips to mix with common citizens, sharing New Year’s greetings and traditional dinners, usually dumplings. The initial, brief reports saying that Mr. Xi had made his trip this year to Yan’an, in the northwestern province of Shaanxi, did not quote him. The microblogs and reports on the Internet merely showed him and his wife, Peng Liyuan, mingling with ruddy-faced farmers and children, and a snippet of video circulating online showed Mr. Xi telling a crowd that he felt very moved to return to the area.

“My first step setting out in life was made in coming here,” Mr. Xi said, according to the video, which showed the same backdrop and people as the photos. “After I came, I stayed for seven years, from 1969 to 1975, and when I left, I left physically, but my heart remained behind.”Even with only those brief remarks, Mr. Xi’s visit spoke abundantly. It was an unapologetic return to the party’s — and to Mr. Xi’s — roots after a year when the party’s revived reverence for Mao and Marxist orthodoxy has kindled contention, and jitters among many liberal intellectuals. “I truly see myself as a Yan’an native,” Mr. Xi said in a 2004 television interview, when he was still a provincial official. “Even now, many of the fundamental ideas and basic features that I’ve developed were formed in Yan’an.”

China Under Xi: Chinese Dream or Second Cultural Revolution?

Jasmine Yin, an admitted princeling and granddaughter of one of Mao Zedong’s favorite generals, wrote in Business Insider: “The proverb tongchuang yimeng — same bed, different dreams — is increasingly being used by young Chinese to describe our opposition to the draconian political — direction the new leadership is taking the country, developments many Chinese are describing as a Second Cultural Revolution. [Source: Jasmine Yin, Business Spectator, March 9, 2016. Jasmine Yin, 19, is a student at Columbia University and granddaughter of the late general Ye Jianying, Marshal of the People’s Liberation Army, chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and head of state of the People’s Republic of China ^^^]

“Communist Party leader Xi Jinping came to power on a promise to fulfil “The China Dream” — rejuvenation of the nation. To his generation, born and raised with the revolution, this means a communal vision of self-sacrifice for the greater glory of the party and state. But my millennial generation has a different dream, one that more resembles the traditional American one: less political interference in our lives, more openness to the outside world, dismantling the detested Great Firewall that blocks indispensable websites such as Google, Facebook and YouTube, and more freedom and democracy like that enjoyed by our peers in Taiwan and Hong Kong. ^^^

“Xi is taking China in a frightening, reactionary, ideologically driven direction. He is creating a personality cult the likes of which hasn’t been seen since Mao and Deng Xiaoping (both of whom earned their credentials leading the revolutionary war, while Xi has never seen a battlefield). His anti-corruption campaign has terrified everyone. With even routine approval of new projects and investments arousing suspicion, the bureaucracy is paralysed. ^^^

“In China, it’s not just about what you did, but who’s in your network of relationships that matters. If your political patron gets in trouble, it doesn’t matter how clean you are, your neck is on the chopping block. In addition to bureaucrats, academics, human-rights lawyers, bloggers, labour-activists and business leaders are also being terrorised. In universities, the government has recruited informers to denounce professors advocating liberal values. Several outspoken progressive academics have lost their jobs. Hundreds of human rights lawyers have disappeared or been arrested. Many business leaders and labour activists have gone missing, presumably detained by anti-corruption investigators. Among the highest-profile cases was that of tycoon Guo Guangchang, popularly known as “China’s Warren Buffet” and the PRC’s 11th-wealthiest person with a net worth of more than $US7 billion ($14.7bn). Guo was detained last December to “assist a judicial investigation” and then simply appeared at his company’s annual meeting a few days later with no explanation. ^^^

“I’ve come to the conclusion that what we need now is a new New Culture Movement, a new China Dream, not a Second Cultural Revolution. A dream that isn’t fuelled by fear, but instead inspired by hope and idealism. I may be a naive teenager, but even Mao said: “You young people, full of vigour and vitality, in the bloom of life, are like the morning sun. Our hope is placed on you.”

Geremie R. Barmé on Xi Jinping, Mao and Chinese Emperors

Ming Emperor Zhengde

Geremie R. Barmé, a professor of Chinese history at the Australian National University, told the New York Times to understand Mr. Xi’s tenure, “you have to have a basic understanding of Mao” and “the dark art of Chinese rule combines elements of dynastic statecraft, official Confucianism, the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist legacy and the mixed socialist-neoliberal reforms of the post-Mao era.” [Source: Jane Perlez, Sinosphere, New York Times,, November 8, 2015 ^]

“Under Xi Jinping, the man I like to call China’s C.O.E., or Chairman of Everything, these traditions are being drawn on to build a China for the 21st century. For those used to thinking about China as being a country that “just wants to be like us,” or as one that fits neatly into the patterns of the Euro-American past, the Xi era is a challenge. For the many students of China who haven’t bothered reading Mao, taking the Marxist tradition seriously or familiarizing themselves with the country’s dynastic legacies, Xi’s version of China is positively discombobulating.” ^

Some people in China refer to Mr. Xi as “Emperor Xi.” Are there similarities? “Since the Mao era, it has been a commonplace for even rather levelheaded analysts and observers to speak of Chinese leaders as emperors or want-to-be emperors. This generates a comfortable metaphorical landscape, one that Chinese friends also often encourage. It puts Chinese political culture and behavior beyond the realm of the normal or knowable. It reaffirms Chinese claims about a unique history and political longevity. Mao was an expert at playing off and against the imperial tradition while sitting above factions that he manipulated in pursuit of his radical political and personal goals. ^

Of course, Xi aspires to something like that, if not more. But he is a long way from having Mao’s charisma or being able to play the system or the people with similar alacrity, though not for want of trying. The official adulation of Xi and the fact that he is omnipresent are reminiscent of the leader complex of other, older socialist states. Emperors were far more constrained and media shy. ^

“There is no doubt that the threnody of the era of “Big Daddy Xi,” as the official media call the C.O.E., is boredom. The lugubrious propaganda chief, Liu Yunshan, the Internet killjoy Lu Wei and Xi himself have together cast a pall over Chinese cultural and intellectual life. At the same time, the party-state is at pains to extol homegrown innovation and creativity. ..Perhaps one of the challenges China poses to our understanding of narratives of development, progress and modernity is that innovative change may well also be possible, if not flourish, under postmodern authoritarianism. Or does one just pickpocket innovation from elsewhere and use state-controlled hyperbole to lay claim to creativity?

Xi Jinping Embraces Confucius and the Classics

In October 2014, Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “Seeking to decipher Mr. Xi, who rarely gives interviews or off-the-cuff comments, China watchers have focused on whether he has the traits of a new Mao, the ruthless revolutionary, or a new Deng Xiaoping, the economic reformer. But an overlooked key to his boldly authoritarian agenda can be found in his many admiring references to Chinese sages and statesmen from millenniums past. Most often, he has embraced Confucius, the sage born around 551 B.C. who advocated a paternalistic hierarchy, to argue that the party should command obedience because it represents “core values” reaching back thousands of years. “He who rules by virtue is like the North Star,” he said at a meeting of officials last year, quoting Confucius. “It maintains its place, and the multitude of stars pay homage.” [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 11, 2014]

Confucius

“By reviving tradition, Mr. Xi is riding China’s nostalgic zeitgeist. Its people have increasingly turned to pre-Communist values while they navigate giddying, contentious changes driven by expanding commerce and inequality. With Mr. Xi likely to be China’s top leader for a decade, officials have been emulating him, and propaganda outlets have exhorted people to imitate his reverence for the ancient past. In May 2014, the overseas edition of the state-run newspaper People’s Daily published a selection of 76 of Mr. Xi’s quotes from Chinese ancients, most often Confucius and Mencius, but also relatively obscure works that suggest a deeper knowledge of the classics.

“When Xi is putting on a political performance, he uses Marxist-Leninist rhetoric and even Mao’s words,” said Kang Xiaoguang, a professor of public administration at Renmin University in Beijing. “But in his bones, what really influences him is not those things but intellectual resources from the traditional classics.” This restoration of tradition has been encouraged by the party, eager to inoculate citizens against Western liberal ideas, which are deemed a decadent recipe for chaos. The Ministry of Education authorized guidelines in March to strengthen instruction in China’s “outstanding traditional culture,” and the party propaganda department has said traditional values are part of “socialist core values.”

“As China grows stronger, this force for restoring tradition will also grow stronger,” said Yan Xuetong, director of the Institute of International Studies at Tsinghua University in Beijing and author of “Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power.” “Where can China’s leaders find their ideas?” he said. “They can’t possibly find them nowadays from Western liberal thought, and so the only source they can look to is ancient Chinese political thinking.”

“Where Mr. Xi absorbed his enthusiasm for the classics is not so clear. He entered adulthood during the Cultural Revolution, when ancient tradition was under assault. But Mr. Xi has said he always liked to read, including Chinese classics, even as a teenager sent to labor in the countryside. Professor Yan of Tsinghua, who also came of age in the Cultural Revolution, said Mao’s campaigns against Confucius helped introduce those very ideas to the young. Visiting a university in Beijing last month, Mr. Xi said he lamented proposals that could reduce mandatory study of Chinese classical literature in school. He said, “The classics should be set in students’ minds so they become the genes of Chinese national culture.”

“Confucius has not always figured in the party’s pantheon. At the height of Mao’s radicalism, Confucius was attacked as an embodiment of poisonous conservatism. Under recent party leaders, Confucius has regained favor — recast as an inoffensively paternal defender of hierarchy, order and discipline. China’s state-backed language-training centers abroad are called Confucius Institutes. But even so, the party has sometimes appeared worried that appealing to an ancient sage might erode its own claims to singular authority. In 2011, the government unveiled a 31-foot bronze statue of Confucius near Tiananmen Square in central Beijing, and then four months later quietly took the statue down.” [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere Blog, New York Times, November 26, 2013 ]

Xi Jinping Pays Homage to Confucius

In November 2013, Xi Jinping visited Qufu, the hometown of Confucius. Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “Xi Jinping, likes venerating his forebears. Mr. Xi has made a reverential visit to a statue of Deng Xiaoping” and “also paid respects to Mao Zedong, and to his own father, a revolutionary who served under Mao.” A year after being named China’s leader, “Xi took political ancestor worship back 25 centuries. He visited Qufu, in Shandong Province, which claims to be the hometown of Confucius, the sage who has been both reviled and honored by the Communist Party as a symbol of traditional values. Mr. Xi made clear that he likes those Confucian traditions — or at least a version of them that can sit easily next to party doctrines and control. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere Blog, New York Times, November 26, 2013 ]

“Mr. Xi visited the Temple of Confucius in Qufu and called together experts to discuss the right way to study Confucius’ teachings on ethics, government and virtuous living, according to China’s official news agency, Xinhua, and other state media. “I want to read these two books carefully,” Mr. Xi said, as he fingered through an annotated copy of The Analects, the collected sayings and dialogues of Confucius, and another book collecting stories and thoughts ascribed to the thinker, who was born about 551 B.C.

“Mr. Xi seems to believe that imposing change demands even greater fealty to the party’s version of tradition.“The Chinese nation possesses a traditional culture that reaches far back in time and can certainly create new glories for Chinese culture,” Mr. Xi said at the meeting with Confucius scholars. But he told them that Confucius should be interpreted through the party’s prism, “using the past to serve the present” so that the sage’s thoughts “can be made to play a positive role in the conditions of the new era.”

Xi visited Qufu to “send a signal that we must vigorously promote China’s traditional culture.” He told scholars that while the West was suffering a “crisis of confidence,” the Communist Party had been “the loyal inheritor and promoter of China’s outstanding traditional culture.” In October 2014, Xi reiterated his reverence for the past at a forum marking 2,564 years since Confucius’ birth. Ancient tradition “can offer beneficial insights for governance and wise rule,” he said in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, where leaders hold congresses and legislative sessions, according to Xinhua. “This is about finding some kind of traditionalist basis of legitimacy for the regime,” Sam Crane, a professor at Williams College in Massachusetts who studies ancient Chinese thought and its contemporary uses, told the New York Times. “It says, ‘We don’t need Western models.’ Ultimately, it is all filtered through the exigencies of maintaining party power.” [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 11, 2014]

Xi Jinping: a Legalist Not a Maoist or Confucian

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: No Chinese leader since has held as much authority — until Xi. But he is not Mao 2.0. A disciplinarian, not a revolutionary, Xi is driven by a need for control. He is a legalist in the tradition of Han Feizi, the philosopher who taught China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, that people are fickle and selfish and must be kept in line through law and punishment. An ethnic nationalist, Xi holds a vision of Chinese revival that draws on allusions to past empires. He speaks in Marxist terms of class struggle and uses Maoist tactics such as self-criticism and rectification, but his brand of communism also promotes Confucius and e-commerce. “The Chinese president sees himself as a savior, anointed to lead the country into a "new era" of greatness propelled by rising prosperity and political devotion. Whether his vision matches reality is another question. The stakes of achieving Xi's grand plan are high. His rule has led to sweeping crackdowns on corruption and political dissent at home and an increasingly strident foreign policy, including provocative naval exercises in the South China Sea and Beijing's tense relations with Washington over trade, spying, technology, and repression of pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times,“Since Mr. Xi became China’s Communist Party leader, he has pursued unyielding policies against dissidents, ethnic minority unrest, corrupt officials and foreign rivals in territorial disputes. The party has also rejected demands for democratic elections for Hong Kong’s leader, and condemned two weeks of pro-democracy street protests in the city as lawless defiance inspired by foreign enemies of China. In his campaign to discipline wayward and corrupt officials, Mr. Xi has invoked Mencius and other ancient thinkers, alongside Mao. Mr. Xi has also shown his familiarity with “Legalist” thinkers who more than 23 centuries ago argued that people should submit to clean, uncompromising order maintained by a strong ruler, much as Mr. Xi appears to see himself. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 11, 2014]

The School of Law, or Legalism was an unsentimental and authoritarian doctrine formulated by Han Fei Zi (d. 233 B.C.) and Li Si (d. 208 B.C.), who maintained that human nature was incorrigibly selfish and therefore the only way to preserve the social order was to impose discipline from above and to enforce laws strictly. The Legalists exalted the state and sought its prosperity and martial prowess above the welfare of the common people. Legalism became the philosophic basis for the imperial form of government. When the most practical and useful aspects of Confucianism and Legalism were synthesized in the Han period (206 B.C. - A.D. 220), a system of governance came into existence that was to survive largely intact until the late nineteenth century. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Xi Jinping Embrace of Han Fei, ‘China’s Machiavelli’

Han Fei

In October, 2014, Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times, “When China’s leader, Xi Jinping, recently warned officials to ward off the temptations of corruption and Western ideas of democracy, he cited Han Fei, a Chinese nobleman renowned for his stark advocacy of autocratic rule more than 2,200 years ago. “When those who uphold the law are strong, the state is strong,” Mr. Xi said, quoting advice that Han Fei offered monarchs attempting to tame disorder. “When they are weak, the state is weak.” He has quoted Han Fei, the most famous Legalist, whose hardheaded advice from the Warring States era made Machiavelli seem fainthearted. And at least twice as national leader, Mr. Xi has admiringly cited Shang Yang, a Legalist statesman whose harsh policies transformed the weak Qin kingdom into a feared empire. Their influence on Mr. Xi” as party leaders endorse “his proposals for “rule of law.” Quite unlike the Western liberal version, Mr. Xi’s “rule of law” looks more like the “rule by law” advocated by the Legalists, said Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society in New York. Mr. Xi wants party power to be applied more equitably and cleanly, but he does not want law to circumscribe that power, said Mr. Schell. This has created an “enormous amount of misinterpretation in the West that thinks ‘rule of law’ is rule of law in a very Western Enlightenment sense of the term,” he said. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 11, 2014]

On Xi Jinping embrace of Han Fei, also known as Han Feizi, Ryan Mitchell wrote in The Diplomat: “The trend has been interpreted in various ways. While many experts would agree with that characterization, even referring to Han Feizi as “China’s Machiavelli,” others see him, and Legalist thought in general, in more positive terms. Scholars Orville Schell and John Delury, in an influential book on the history of Chinese reform efforts, credit “pragmatic” Legalist thought of as being behind both much of China’s historical success and its ongoing rebirth as a great nation. For Confucians, who focus on ideals of loyalty, righteousness, and benevolence, little could be more repugnant than the Legalist position that “if a wise ruler masters wealth and power, he can have whatever he desires.” [Source: Ryan Mitchell, The Diplomat, January 16, 2015; Ryan Mitchell is pursuing a Ph.D. in Law at Yale, where his research focuses on political philosophy and international law.

“Yet Han Feizi’s ideas, and Xi’s uses of them, are far from mere illiberal posturing. Even the remarks cited by the New York Times were actually a warning by Xi to the country’s high level political leaders that “when those who uphold the law are strong, the state is strong. When they are weak, the state is weak.” The statement is at once striking, suggestive, and highly ambiguous. In this sense, Xi’s use of ancient scholarship resembles the other activities characteristic of his unique administration. Observers are divided on how to interpret his high-intensity crackdown on corruption, nearly unprecedented personal popularity, and high-profile reforms aiming for “the rule of law.” Thus, his use of reformist-sounding language can be more than enough to prompt guarded optimism among observers both domestic and foreign. Other analysts, however, remain highly skeptical; pointing to several other statements where Xi vows to crush dissent, resist the West, and ensure ideological unity.” ^|^

“There is no clear consensus on what” Xi Jinping “actually thinks or believes. That is why the most valuable insight to gain from his Legalist references may actually relate to a more basic question. If Xi really is especially influenced by the Legalist School, it means two important things for his future trajectory. First, neither his calls for reform nor his illiberal pronouncements should be taken as simple statements about what he believes. Instead, he is likely using different forms of compromise language that various factions can agree upon. Xi’s patchwork political platform can be seen as maintaining his own place of authority, largely by avoiding the potential wrath of the Communist Party’s elders and many eliteinterest groups: the “dragon” whose scales he risks rubbing the wrong way. Secondly, as a ruler Xi’s signature initiatives – especially his dramatic and escalating crackdown on official corruption – probably do not reflect either high idealism or a mere power grab. Xi undoubtedly does have a vision for where he wants to take his country, his own “Chinese Dream,” but he is unlikely to be so foolish as to try to realize that dream too early. In order to achieve his goals, Xi first has to “master wealth and power,” and a robust, predictable legal system is one key to such mastery. ^|^

“As a recent People’s Daily editorial admits, it is simply beside the point to ask whether or not Xi intends for “the rule of law” to limit the Party’s authority, or his own as the Party’s representative. Very pragmatically – very much like a Legalist – Xi is looking for formulas that can achieve his goals for the nation. For now, the wealth of corrupt officials has to be seized, and the power of elites over the law has to be abolished. It doesn’t much matter whether that process is called liberal or conservative, left or right, traditional or modern. What matters, at least for the moment, is whether or not it works.” ^|^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Mao Poster: Nolls website; Time cover: Time magazine

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021