XI JINPING’S LEADERSHIP SKILLS

Xi Jinping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or CPC) in November 2012. He became Chinese president in March 2013 and over time claimed other titles to become China’s unquestioned leader to such a degree he has been called a new Mao and a new Emperor. After he became the leader of China, Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: "What is clear is that Xi has excelled at quietly rising through the ranks by making the most of two facets: He has an elite, educated background with links to communist China’s founding fathers that are a crucial advantage in the country’s politics, and at the same time he has successfully cultivated a common-man mystique that helps him appeal to a broad constituency. He even gave up a promising Beijing post in his late 20s to return to the countryside. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012 ]

"Xi is at ease in groups, in contrast to China’s typically stiff and aloof leaders, such as President Hu Jintao. “Xi was chosen in part because he has the large, assertive, confident personality to lead in that kind of strategy,” said Andrew Nathan, an expert on Chinese politics at New York’s Columbia University. Former U.S. ambassador to Beijing Jon Huntsman told AP Xi is a man “who is quite different from Hu Jintao” in that Xi appears at ease. “He’s someone who you can connect with."

A friend of Xi told the Times of London, “He is a neutral person who has always avoided showing any strong political opinions, neither supporting or opposing people or their policies openly. He is not someone with great charisma, neither will he cause any harm.” Xi speaks English. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paul said he was friendly toward business and is a “guy who really knows how to get over the goal line.”

Barbara Demick and David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Xi worked his way into the graces of the Communist Party, his rise fueled by a workaholic drive and apparent indifference to privilege. He left few mistakes or enemies in his trail." He "is often depicted as another in a line of colorless cadres, but his life story is rich with contrasts. A passionate scholar of Marxist theory who preaches the need for young Chinese to study more Communist ideology, he nonetheless champions private enterprise. [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

And in a party renowned for its chronic corruption, he had a reputation for staying clean. In 2007 he was chosen to replace Shanghai's disgraced party chief, Chen Liangyu. He attained a spot on the powerful Politburo Standing Committee later that year. "I'd be surprised if you were able to dig up any dirt on him other than some stolen library books," said the friend. "He carries with him a very grand confidence," said Huntsman. who met with Xi on many occasions. "He exudes a sense of warmth, even charm, that I think will serve him well in power."

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: XI JINPING factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S EARLY LIFE, CHARACTER AND CAVE HOME YEARS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FAMILY, HARVARD EDUCATED DAUGHTER AND FAMILY WEALTH factsanddetails.com; PENG LIYUAN: XI XINPING'S WIFE AND CHINA’S GLAMOROUS FIRST LADY factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BEFORE HE BECAME THE LEADER OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING BECOMES THE LEADER OF CHINA: HIS INNER CIRCLE, STYLE AND DIRECTIONS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S AUTHORITARIANISM AND TIGHT GRIP ON POWER factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING'S STYLE, LEADERSHIP AND PERSONALITY CULT factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S DOMESTIC POLICY: CHINESE DREAM, ECONOMICS AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, MAOISM AND CONFUCIUS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S ANTI-CORRUPTION DRIVE factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, HUMAN RIGHTS AND OPPOSITION TO WESTERN IDEAS factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING, THE MEDIA AND THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF HIM factsanddetails.com; XI JINPING’S FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com; LI KEQIANG factsanddetails.com; CHINA'S POLITBURO STANDING COMMITTEE MEMBERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future” by Chun Han Wong Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China” (English Version) by the Chinese government Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018" by Alfred L. Chan Amazon.com; “CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Xi: A Study in Power: A Study in Power” by Kerry Brown Amazon.com; “Snake Oil: How Xi Jinping Shut Down the World” by Michael P Senger Amazon.com; “Xi Jinping” by Willy Lam Amazon.com; “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” by François Bougon Amazon.com

Xi Jinping’s Political Career

Mr Xi's official life story emphasizes his capacity for hard work and his fearless tackling of corruption as a young official in eastern Fujian province. From 1969-1975, according to China.org, Xi was as an educated youth sent to the countryside at Liangjiahe Brigade, Wen'anyi Commune, Yanchuan County, Shaanxi Province, and served as Party branch secretary. From 1975 to 1979 he was a student of basic organic synthesis at the Chemical Engineering Department of Tsinghua University. From 1979 to1982 Xi was Secretary at the General Office of the State Council and the General Office of the Central Military Commission (as an officer in active service). From 1982 to 1983 he was Deputy secretary of the CPC Zhengding County Committee, Hebei Province. From 1983 to 1985 he was Secretary of the CPC Zhengding County Committee, Hebei Province.

with family in 1976 An extended look at Mr. Xi’s past,” Wong and Jonathan Ansfield wrote in the New York Times, ‘shows that his rise has been built on a combination of political acumen, family connections and ideological dexterity. Like the country he will run, he has nimbly maintained the primacy of the Communist Party, while making economic growth the party’s main business.” [Source: Edward Wong and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, January 23, 2011]

Xi first made a name for himself when he served as a party boss in a rural Zhengding county in Hebei Province near Beijing in the 1980s, a period of time when he saw a lot of national party chief Hu Yaobang. In Hebei Xi promoted local tourism and rural enterprise, but ran up against the conservative provincial leader. Political expert Zhang Xiaojin told The Guardian Xi may have sought the unglamorous post in Hebei province to shake off suggestions of benefiting from his family name.

Xi worked his way up the party ranks in central China and went on to a succession of more senior jobs in Fujian province on the east coast. From there, he transferred to the neighboring province of Zhejiang, a hive of private manufacturing enterprises, where he worked with business and gained a reputation for fighting corruption. In 2007, he was catapulted to the mega-city of Shanghai after the party secretary there was ousted in a major political-corruption scandal. [Source: Fenby, Op. Cit]

The rise of Xi has been smoothed by his connections. Being the son of Xi Zhongxun was a big help. Xi Zhongxun helped Hu Jintao rise through the ranks. The younger Xi had barely settled into his job as party leader of Shanghai before he was elevated to the politburo standing committee in 2007 and moved to Beijing. He was given political responsibility for the 2008 Beijing Olympics and for supervising Hong Kong as well as being entrusted with the politically important job of president of the party school, the highest institution training officials of the Communist party. [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Michael Wine, New York Times, October 18, 2010]

Xi Jinping’s Efforts to Join the Communist Party

Xi joined the Communist Party at the age of 20 before he entered university. He was rejected for Communist Party membership seven times by his own count due to his father’s political problems and was accepted only after he won endorsement by the township secretary of the Communist Youth League he befriended. In January, 1974, he gained full Party membership and became secretary of his village.

Barbara Demick and David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, "Despite the years of persecution, Xi still sought out the Communist Party's approval. He applied eight times to join its youth league, but nobody would accept his paperwork until he invited a young man who served as the local party secretary for a fried egg and steamed bread in the cave and pleaded his case. Xi finally gained party membership in 1974 after the an order was given not to penalize people for their parents misdeed. [Source: Barbara Demick and David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “His drive to join the Party baffled some of his peers. A longtime friend who became a professor later told an American diplomat that he felt “betrayed” by Xi’s ambition to “join the system.” According to a U.S. diplomatic cable recounting his views, many in Xi’s élite cohort were desperate to escape politics; they dated, drank, and read Western literature. They were “trying to catch up for lost years by having fun,” the professor said. He eventually concluded that Xi was “exceptionally ambitious,” and knew that he would “not be special” outside China, so he “chose to survive by becoming redder than the red.” After all, Yang Guobin told me, referring to the sons of the former leaders, “the sense of ownership did not die. A sense of pride and superiority persisted, and there was some confidence that their fathers’ adversity would be temporary and sooner or later they would make a comeback. That’s exactly what happened.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

Xi at the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1975

Xi Jinping’s Rise After His Father’s Rehabilitation

By the time Mao died in 1976 Xi's father had been restored to office. After graduating from Tsinghua Xi secured a plum position as secretary to Defense Minister Geng Biao, one of his father’s old comrades, working in the general office of the state council—the equivalent of the government—and the central military commission. Geng Biao was a powerful military bureaucrat allied with Mr. Xi’s father. Xi worked for three years as Geng’s private secretary when Geng was Minister of Defense.

Xi's father was politically rehabilitated in 1978 and later appointed by Deng Xiaoping as party secretary for Guangdong province, implementing economic reforms in an area that was to become the engine of the new China. No longer a liability, his father used his connections to get Xi a plum job as an assistant to Geng Biao, a fellow revolutionary who headed the powerful Central Military Commission.

Xi then began an odyssey through China, accepting two- to five-year stints from the party in different provinces as he worked his way up the ladder. Unlike other party members of his age group, he didn't drink much or womanize, said the friend from his younger days. He dressed plainly and rode a bicycle even after he ranked high enough for an official car. "There was nothing flashy about him," said the friend. "It was as though he always had a sense of mission about him."

Xi Jinping Early Political Career

Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “After his father was rehabilitated in 1978, Xi Jinping worked as a party official in several coastal provinces. It was there he saw firsthand how market reforms brought wealth and rising living standards — but also an explosion of corruption. The experience would stay with him. In 2012, shortly after Xi came to power, he went on a "southern tour" to Shenzhen, retracing the footsteps of Deng Xiaoping, who in the 1970s and '80s oversaw China’s economic opening. But Xi's vision of reform was different. In his view, China's Communist Party was in crisis: Inequality and corruption were rampant and people had abandoned their ideals. The nation risked repeating the fate of the Soviet Union, he said in a 2012 speech, where "no one was man enough" to assert ideological control and resist "Western ideas" like democracy, separation of powers or rule of law. China needed a strong "man" to reassert the party's power and inspire the masses. [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Xi Jinping’s pedigree had exposed him to a brutal politics—purges, retribution, rehabilitation—and he drew blunt lessons from it. In a 2000 interview with the journalist Chen Peng, of the Beijing-based Chinese Times, Xi said, “People who have little experience with power, those who have been far away from it, tend to regard these things as mysterious and novel. But I look past the superficial things: the power and the flowers and the glory and the applause. I see the detention houses, the fickleness of human relationships. I understand politics on a deeper level.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

Geng Biao

“Xi’s siblings scattered: his brother and a sister went into business in Hong Kong, the other sister reportedly settled in Canada. But Xi stayed and, year by year, invested more deeply in the Party. After graduating, in 1979, he took a coveted job as an aide to Geng Biao, a senior defense official whom Xi’s father called “my closest comrade-in-arms” from the revolution. Xi wore a military uniform and made valuable connections at Party headquarters.” According to a professor who knew him Xi divorced his first wife Ke Xiaoming when Ke decided to move to England and Xi stayed behind. ^^^

“China’s revolutionaries were aging, and the Party needed to groom new leaders. Xi told the professor that going to the provinces was the “only path to central power.” Staying at Party headquarters in Beijing would narrow his network and invite resentment from lesser-born peers. In 1982, shortly before Xi turned thirty, he asked to be sent back to the countryside, and was assigned to a horse-cart county in Hebei Province. He wanted to be the county secretary—the boss—but the provincial chief resented privileged offspring from Party headquarters and made Xi the No. 2. It was the Chinese equivalent of trading an executive suite at the Pentagon for a mid-level post in rural Virginia. ^^^

Xi Jinping in Hebei

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: Xi took the unusual step in 1982 “of jumping to a lowly post in rural Hebei province, because he wanted to ‘struggle, work hard, and really take on something big,” Xi told Elite Youth magazine’s now-deceased editor Yang Xiaohuai. Xi landed in the rural town of Zhengding, where people traveled by horse cart. Xi biked around town dressed like an army cook and insisted he be introduced only as county party secretary without reference to his family links, former colleague Wang Youhui recalled. “He always paid for his food. He didn’t want any special treatment,” state media quoted Wang as saying years later." [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

While there, he made the most of state broadcaster China Central Television’s plans to film an adaptation of the classical Chinese novel “Dream of Red Mansions.” Hoping to create a tourist attraction, Xi built a full-scale reproduction of the sprawling estate at the heart of the tale. “You could tell Xi was thinking ahead. By doing this, he created lots of jobs and lots of revenue for Zhengding back when there was very little here,” said Liang Qiang, a senior caretaker at the film set, which still draws tourists. [Ibid]

Osnos wrote: “Within a year, though, Xi was promoted, and he honed his political skills. He gave perks to retired cadres who could shape his reputation; he arranged for them to receive priority at doctors’ offices; when he bought the county’s first imported car, he donated it to the “veteran-cadre office,” and used an old jeep for himself. He retained his green Army-issue trousers to convey humility, and he learned the value of political theatrics: at times, “if you don’t bang on the table, it’s not frightening enough, and people won’t take it seriously,” he told a Chinese interviewer in 2003. He experimented with market economics, by allowing farmers to use more land for raising animals instead of growing grain for the state, and he pushed splashy local projects, including the construction of a television studio based on the classic novel “A Dream of Red Mansions.”“^^^

Bodeen wrote: "Xi’s elite background plugged him into to a web of personal connections that were especially important early in his career, ensuring support from Beijing for local projects. As party leader, Xi should easily command the respect of officials and the military, in part because of deference to his father’s status. At the same time, Xi’s years in the provinces protect him from accusations of pure nepotism and lend him credibility as someone who understands the struggles of working Chinese and private businessmen who are creating the bulk of new jobs."

Xi Jinping in Fujian Province

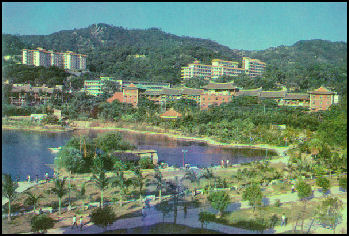

Fujian Province

By the early 1980s, Xi was identified by party elders as a prospective future leaders. The party sent him to Fujian Province, across the Taiwan Strait from Taiwan, where he served in three cities. Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: With help from his father, Xi jumped in 1985 to a vice mayorship in the port of Xiamen, then at the forefront of economic reforms. Over the next 17 years, he built a reputation for attracting investment and eschewing the banqueting expected of Chinese officials. He hung a banner saying “Get it done” in a provincial office lobby. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “By 1985, Xi was ready for another promotion, but the provincial Party head blocked him again, so he moved to the southern province of Fujian, where one of his father’s friends was the Party secretary, and could help him. Not long after he arrived, he met Liao Wanlong, a Taiwanese businessman, who recalled, “He was tall and stocky, and he looked a little dopey.” Liao, who has visited Xi repeatedly in the decades since, told me, “He appeared to be guileless, honest. He came from the north and he didn’t understand the south well.” Liao went on, “He would speak only if he really had something to say, and he didn’t make casual promises. He would think everything through before opening his mouth. He rarely talked about his family, because he had a difficult past and a disappointing marriage.” Xi didn’t have a questing mind, but he excelled at managing his image and his relationships; he was now meeting foreign investors, so he stopped wearing Army fatigues and adopted a wardrobe of Western suits. Liao said, “Not everyone could get an audience with him; he would screen those who wanted to meet him. He was a good judge of people.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

“The posting to the south put Xi closer to his father. Since 1978, his father had served in neighboring Guangdong, home to China’s experiments with the free market, and the elder Xi had become a zealous believer in economic reform as the answer to poverty...His son avoided overly controversial reforms as he rose through the ranks. “My approach is to heat a pot with a small, continuous fire, pouring in cold water to keep it from boiling over,” he said. In 1989, a local propaganda official, Kang Yanping, submitted a proposal for a TV miniseries promoting political reform, but Xi replied with skepticism. According to “China’s Future,” he asked, “Is there a source for the opinion? Is it a reasonable point?” The show, which Xi predicted would leave people “discouraged,” was not produced. He also paid special attention to cultivating local military units; he upgraded equipment, raised subsidies for soldiers’ living expenses, and found jobs for retiring officers. He liked to say, “To meet the Army’s needs, nothing is excessive.” ^^^

Xiamen in Fujian Province in the 1980s

From 1985-1988, according to China.org, Xi was a Member of the Standing Committee of the Municipal Party Committee and vice mayor of Xiamen, Fujian Province. From 1988 to 1990 Xi was Secretary of the CPC Ningde Prefectural Committee, Fujian Province. From 1990-1993 he was Secretary of the CPC Fuzhou Municipal Committee and chairman of the Standing Committee of the Fuzhou Municipal People's Congress, Fujian Province. In 1993-1995 Xi was a Member of the Standing Committee of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee, secretary of the CPC Fuzhou Municipal Committee and chairman of the Standing Committee of the Fuzhou Municipal People's Congress. In 1995-1996 he was Deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee, secretary of the CPC Fuzhou Municipal Committee and chairman of the Standing Committee of the Fuzhou Municipal People's Congress.

From 1996 to 1999 Xi was Deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee. In 1999-2000 he was Deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee and acting governor of Fujian Province. In 2000-2002 he was Deputy secretary of the CPC Fujian Provincial Committee and governor of Fujian Province (1998-2002 Studied Marxist theory and ideological education in an on-the-job postgraduate program at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tsinghua University and graduated with an LLD degree).

Xi Jinping in Iowa

In 1985, in what is believed to have been his first trip outside of China, Xi led an animal-feed delegation in Muscatine, Iowa, where he toured farms, visited rotary clubs and joked about receiving a gift of popcorn. The trip was part of a sister arrangement with the Chinese province where he worked, according to NPR. [Source: Christina Sterbenz, Business Insider April 1, 2015 -]

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian: It was as deputy secretary of Zhengding county that he visited Muscatine, a US town of 23,000 until now best known for its melons and Mark Twain's brief sojourn there in 1855. "He was a very polite and kind guy. I could see someone very devoted to his work—there was no golfing on that trip, that's for sure," said Eleanor Dvorchak, who hosted Xi in her son's old room, where he slept amid football wallpaper and Star Trek figurines. "He was serious. He was a man on a mission." Sarah Lande, who organised the trip, said his confidence was obvious even through a translator. "You could tell he was in charge—he seemed relaxed and welcoming and able to handle things," she said. "He had the words he wanted to express himself easily." [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 12, 2012]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “He spent two weeks in Iowa as part of an agricultural delegation. In the town of Muscatine, he stayed with Eleanor and Thomas Dvorchak. “The boys had gone off to college, so there were some spare bedrooms,” Eleanor told me. “He was looking out the window, and it seemed like he was saying, ‘Oh, my God,’ and I thought, What’s so unusual? It’s just a split-level,” she said. Xi did not introduce himself as a Communist Party secretary; his business card identified him as the head of the Shijiazhuang Feed Association. In 2012, on a trip to the U.S. before becoming top leader, he returned to Muscatine, to see Dvorchak and others, trailed by the world press. She said, “No one in their right mind would ever think that that guy who stayed in my house would become the President. I don’t care what country you’re talking about.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

Xi Jinping in Iowa in 1985

Eleanor described Xi as "humble. "He did not complain,” she told The New York Times. “Everything, no matter what, was very acceptable to him." Xi returned to Muscatine in 2012. Upon reuniting with the Dvorchaks, and other "old friends," Xi told the Muscatine Journal: "You were the first group of Americans I came into contact with," he said. "To me, you are America." -

Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, took politicized trips to the West. In the '80s, Zhongxun went to New York City, Washington D.C., Iowa, Colorado, California, and Hawaii. "The father struck me as a very thoughtful and humane and dedicated person, and I'm hoping the apple doesn't fall far from the tree." Jan Berris from the National Committee on US-China Relations, who accompanied Xi's dad in the US, told NPR.

Xi Jinping as Governor of Fujian Province

As governor of Fujian, Xi Xinping played a central role in encouraging Taiwan businesses to invest on the mainland. Xi tried to dramatically reverse the government’s poor reputation for accountability by clearing a backlog of citizen complaints in a one-day blitz in the city of Quzhou. He set up 15 temporary offices to address complaints over land seizures, job benefits and other issues, drawing 300 petitioners and resolving 70 cases. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015}

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: Mr Xi’s official life story emphasises his capacity for hard work, his fearless tackling of corruption as a young official in eastern Fujian province and that he missed the birth of his daughter in 1992 because he was busy in the front line of flood relief efforts. As governor of Fujian he played a central role in encouraging Taiwan businesses to invest on the mainland.[Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, October 27 2012]

Wong and Ansfield wrote in the New York Times, “As governor of Fujian Xi courted investment from across the Taiwan Strait, and through this and other posts, built his business credentials. "He's a cool, rational guy who realizes and knows China needs foreign investment and technology," said Sidney Rittenberg Sr., an American consultant who successfully appealed to Xi to resolve a business dispute for a consortium of U.S. companies building a power project in Fujian in 2002. For 14 years, Xi also supervised the local military command.” His exposure to the Taiwan territorial issue “may shade his views on cross-strait relations in the direction of flexibility,” said Alice L. Miller, a scholar of Chinese politics at the Hoover Institution.

China scholar Willy Wo-Lap Lam told the New York Times: “He spent 15 years in Fujian, rising to the level of governor, before leaving in 2002. Those 15 years were quite mediocre. He did nothing remarkably reformist or noteworthy. Xi’s track record in Zhejiang from 2002 to 2007 was better. But if you compare him to high-profile cadres such as Wang Yang, who was party secretary of Guangdong, he was cautious to a fault. Xi was anxious not to appear to be excessively reformist. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, June 2, 2015]

Corruption Under Xi Jinping in Fujian

Book about corruption in Fujian while Xi was governor there

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Xi prosecuted corruption at some moments and ignored it at others. A Chinese executive told the U.S. Embassy in Beijing that Xi was considered “Mr. Clean” for turning down a bribe, and yet, for the many years that Xi worked in Fujian, the Yuanhua Group, one of China’s largest corrupt enterprises, continued smuggling billions of dollars’ worth of oil, cars, cigarettes, and appliances into China, with the help of the Fujian military and police. Xi also found a way to live with Chen Kai, a local tycoon who ran casinos and brothels in the center of town, protected by the police chief. Later, Chen was arrested, tried, and sentenced to death, and fifty government officials were prosecuted for accepting bribes from him. Xi was never linked to the cases, but they left a stain on his tenure. “Sometimes I have posted colleagues wrongly,” he said in 2000. “Some were posted wrongly because I thought they were better than they actually were, others because I thought they were worse than they actually were.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015 ^^^]

According to the New York Times: ‘Some ambitious investments drew national scrutiny while Xi governed Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian. City leaders signed a contract with Li Ka-shing, the Hong Kong real estate tycoon, to redevelop the old city quarter, but that fizzled after a public outcry. A new international airport grossly overshot its budget. Nor was Mr. Xi untainted by corruption scandals. One party investigation into bribe-taking in Ningde and Fuzhou, publicized years after he left Fujian, toppled two former city leaders whom Mr. Xi had promoted.”

Xi Jinping’s Rise in the Communist Party

Wong and Ansfield wrote in the New York Times, “Mr. Xi climbed the ladder by building support among top party officials, particularly those in Mr.Jiang’s clique, all while cultivating an image of humility and self-reliance despite his prominent family ties, say officials and other party members who have known him.” [Source: Wong and Ansfield, Op. Cit]

“His subtle and pragmatic style was seen in the way he handled a landmark power project teetering on the edge of failure in 2002, when he was governor of Fujian, a coastal province. The American company Bechtel and other foreign investors had poured in nearly $700 million. But the investors became mired in a dispute with planning officials.” [Ibid]

“After ducking foreign executives” repeated requests for a meeting, Mr. Xi agreed to chat one night in the governor’s compound with an American business consultant on the project [Sidney Rittenberg Jr.] Mr. Xi explained that he could not interfere in a dispute involving other powerful officials. But he showed that he knew the project intimately and supported it, promising to meet the investors “after the two sides have reached an agreement.” That spurred a compromise that allowed the power plant to begin operating.” [Ibid]

Over the years, Mr. Xi built his appeal on “the way he carried himself in political affairs,” Zhang Xiaojin, a political scientist at Tsinghua University told the New York Times. “On economic reforms and development, he proved rather effective. On political reforms, he didn’t take any risks that would catch flak.” [Ibid] Wong and Ansfield wrote: “Mr. Xi also emerged as a convenient accommodation to two competing wings of the party: those loyal to Mr. Hu and those allied with Mr. Jiang, who in China’s collective leadership had an important role in naming Mr. Hu’s successor. Mr. Xi’s elite lineage and career along the prosperous coast have aligned him more closely with Mr. Jiang. But like Mr. Hu, Mr. Xi also spent formative years in the provincial hinterlands. Mr. Hu was once close to Mr. Xi’s father, a top Communist leader during the Chinese civil war.” [Ibid]

“Back in Beijing, top leaders were watching out for Mr. Xi. He actually finished last when party delegates voted for the 344 members and alternates of the Party Central Committee in 1997 because of general hostility toward princelings. But Mr. Xi slipped in as an alternate anyway. Mr. Jiang, the party leader, and his power broker, Zeng Qinghong, helped back Mr. Xi’s continued rise, said Cheng Li, a scholar of Chinese politics at the Brookings Institution in Washington.” [Ibid]

Xi Jinping in Zhejiang Province

Zhejiang Province

After Fujian Xi’s next assignment was as provincial party boss up in Zhejiang a coastal province known for its concentration of freewheeling entrepreneurs, lively civil society, non-communist candidates for local assemblies and a thriving underground church movement. Wong and Ansfield wrote in New York Times, “There, too, the economy was humming. Mr. Xi hewed to Beijing’s initiatives to embrace private entrepreneurs. He also hitched his star to homegrown private start-ups that have since gone global and boasted of traveling to every county in Zhejiang Province. AP reported: "Xi was seen as allowing minor local administrative reforms, while not initiating any of them."

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Xi proved adept at navigating internal feuds and alliances. After he took over the economically vibrant province of Zhejiang, in 2002, he created policies intended to promote private businesses. He encouraged taxi services to buy from Geely, the car company that later bought Volvo. He soothed conservatives, in part by reciting socialist incantations. “The private economy has become an exotic flower in the garden of socialism with Chinese characteristics,” he declared. “ [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 6, 2015]

In 2002 according to China.org Xi served as deputy secretary of the CPC Zhejiang Provincial Committee and acting governor of Zhejiang Province. From 2002 to 2003 he was Secretary of the CPC Zhejiang Provincial Committee and acting governor of Zhejiang Province. From 2003 to 2007 he was Secretary of the CPC Zhejiang Provincial Committee and chairman of the Standing Committee of the Zhejiang Provincial People's Congress.

Xi's support for the private sector intensified after he was named the top official of Zhejiang. Xi famously became a booster for Geely, a local automaker that would eventually purchase Volvo from the Ford Motor Company.’soon after his arrival in late 2002, he visited Geely, then the province’s sole carmaker. The firm’s indefatigable founder, Li Shufu, had just begun to receive some financing from state banks. “If we don’t give additional strong support to companies like Geely, then whom are we going to support?” Mr. Xi remarked.

“Mr. Xi bestowed early recognition, too, on Ma Yun, founder of Alibaba, now an e-commerce giant and Yahoo’s partner in China. After he left Zhejiang in 2007 to become the top official in Shanghai, Mr. Xi extended an invitation to Mr. Ma: “Can you come to Shanghai and help us develop?” [Ibid]

“At the time, party authorities were pushing private companies to form party cells, part of Mr. Jiang’s central vision to bring companies and the party closer. Officials under Mr. Xi parceled out vanity posts to entrepreneurs, granting some the coveted title of local legislative delegate. Mr. Xi also cautiously supported small-scale political reforms in Zhejiang, where democratic experiments were percolating at the grass roots.” [Ibid]

“When cadres in one village in Wuyi County allowed villagers to elect three-person committees to supervise their leaders, Mr. Xi took notice. He issued pivotal directives that helped extend the obscure pilot program, said Xiang Hanwu, a county official. The system won praise from the Central Party School, where rising cadres are trained. In August, Zhejiang approved a provincewide rollout, though with additional party controls... Mr. Xi also got an important career boost from Zhejiang’s push to forge business ties with poorer provinces inland. He led groups of wealthy Zhejiang businessmen who met with officials in western provinces, winning points with other provincial leaders. [Ibid]

Xi Jinping Jumps to the Politburo

In 2007, Xi was appointed to Secretary of the CPC Shanghai Municipal Committee. In 2007 and 2008 he was a Member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, member of the Secretariat of the CPC Central Committee, and president of Party School of the CPC Central Committee. From 2008 to 2010 Xi was a Member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, member of the Secretariat of the CPC Central Committee, vice president of PRC and president of Party School of the CPC Central Committee. In 2010, he was appointed Vice chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission.

When asked by a reporter, in 2002, whether he would be a top leader within the decade Xi said, "Are you trying to give me a fright?" However, Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian: “An acquaintance who spoke to WikiLeaks claimed Xi always had his "eye on the prize" of a major party post. He transferred to southern Fujian province in 1985, climbing steadily upwards over 17 years. Most of his experience has been earned in China's relatively prosperous, entrepreneurial coastal areas, where he courted investors and built up business, proving willing to adopt new ideas. The former US treasury secretary Hank Paulson called him "the kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line". [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 12, 2012]

Wong and Ansfield wrote in New York Times, “For years before a party congress in October 2007, Mr. Xi was not deemed the front-runner to succeed Hu Jintao as party leader. The favorite was Li Keqiang, a protégé of Mr. Hu. But Mr. Xi’s political capital surged in March 2007 when he was handed the job of party boss in Shanghai after a pension fund scandal had toppled the previous leader Chen Liangyu. [Source: Wong and Ansfield, Op. Cit]

"Shanghai was the power base of Mr. Jiang and Mr. Zeng. During his short seven-month stint there, before he joined the elite Politburo Standing Committee in Beijing, Mr. Xi helped ease the aura of scandal on their turf, while stressing Beijing’s prescriptions for the kind of measured growth favored by Mr. Hu...It was a balancing act of a kind that had served him well for decades.” [Ibid]

Barely six months after he took charge of Shanghai Xi was elevated to the politburo standing committee—the top political body—signalled that he was expected to succeed Hu. Many had expected Li Keqiang—now expected to become premier—to take the position. He leapfrogged Li perhaps because Li seen too much Hu's protege. Xi was the consensus candidate in a system built on collective decision making. But it wasn't always so easy. In the vote for membership of the central committee in 1997, amid hostility to princelings, connections won Xi only a place as an alternate.

Xi's other titles included: Alternate member of the Fifteenth CPC Central Committee, and member of the Sixteenth CPC Central Committee. Member of the Seventeenth CPC Central Committee, member of the Political Bureau and its Standing Committee, and member of the Secretariat of the Seventeenth CPC Central Committee.

11th National People's Congress in 2008, where Xi Jinping was named a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee

Xi Jinping Views

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: It is in the nature of China’s politics that relatively little is known about Xi’s policy leanings. He is not associated with any bold reforms. Aspiring officials get promoted by encouraging economic growth, tamping down social unrest and toeing the line set by Beijing, not through charismatic displays of initiative. Xi’s resume in provincial posts suggest he is open to private industry and some administrative reforms as long as they don’t jeopardize the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Akira Fujino wrote on the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Well-informed sources in Beijing suggest Xi is more conservative than Hu Jintao, and most likely will place top priority on maintaining the status quo to protect the vested interests of the privileged , Xi has made remarks praising the old-guard thinking and the thoughts of Mao Zedong.”

Willy Lam of the Jamestown Foundation wrote in China Brief: “Unlike his father, former vice-premier Xi Zhongxun, who is a bona fide “rightist” and ally of the late party chief Hu Yaobang, Xi is believed to harbor much more conservative views When delivering speeches in his capacity as President of the CCP Central Party School, Xi has indicated that while cadres must pass muster inmorality and “Marxist rectitude” in addition to professional competence, the former comes before the latter. This is reminiscent of Chairman Mao’s famous dictum that officials should be both “red and expert.” The Vice-President has repeatedly urged up-and-coming cadres to steep themselves in Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. One of Xi’s favorite homilies is that leading officials must “firm up their political cultivation and boost the resoluteness of their political beliefs, the principled nature of their political stance” as well as the reliability of their political loyalty.”“ [Source: Willy Lam, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, December 17, 2010]

Wong and Ansfield wrote in New York Times, “Since joining the inner sanctum in Beijing, Mr. Xi has reinforced his longstanding posture as a team player. As president of the Central Party School, Mr. Xi recently made a priority of teaching political morality based on Marxist-Leninist and Maoist ideals, a resurgent trend in the bureaucracy.” [Source: Wong and Ansfield, Op. Cit]

“There is little in his record to suggest that he intends to steer China in a sharply different direction. But some political observers also say that he may have broader support within the party than Mr. Hu, which could give him more leeway to experiment with new ideas. At the same time, there is uncertainty about how he may wield authority in a system where power has grown increasingly diffuse. Mr. Xi also has deeper military ties than his two predecessors, Mr. Hu and Jiang Zemin, had when they took the helm. For much of his career, Mr. Xi, 57, presided over booming areas on the east coast that have been at the forefront of China’s experimentation with market authoritarianism, which has included attracting foreign investment, putting party cells in private companies and expanding government support for model entrepreneurs. This has given Mr. Xi the kind of political and economic experience that Mr. Hu lacked when he ascended to the top leadership position.” [Ibid] “On several occasions Xi seems to have slighted Hu so as to play up his special relationship with ex-president Jiang. During a tête-à-tête with Angela Merkel in Berlin in October 2009, Xi presented the German Chancellor with two books written by Jiang before passing along the ex-president’s greetings to Merkel. According to official Chinese news agencies, the Vice-President did not even once mention Hu during the entire meeting.” [Ibid]

Xi Jinping and Fighting Corruption in China

Bloomberg News reported: “Throughout his career Xu built a reputation for clean government. He led an anti-graft campaign in the rich coastal province of Zhejiang, where he issued the “rein in” warning to officials in 2004, according to a People’s Daily publication. In Shanghai, he was brought in as party chief after a 3.7 billion- yuan ($582 million) scandal. In a speech on March 1 2012 before about 2,200 cadres at the central party school in Beijing where members are trained, Xi Jinping said that some were joining because they believed it was a ticket to wealth. “It is more difficult, yet more vital than ever to keep the party pure,” he said, according to a transcript of his speech in an official magazine. [Source: Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012]

A 2009 cable from the U.S. Embassy in Beijing cited an acquaintance of Xi’s saying he wasn’t corrupt or driven by money. Xi was “repulsed by the all-encompassing commercialization of Chinese society, with its attendant nouveau riche, official corruption, loss of values, dignity, and self- respect,” the cable disclosed by Wikileaks said, citing the friend. Wikileaks publishes secret government documents online. [Ibid]

Increasing resentment over China’s most powerful families carving up the spoils of economic growth poses a challenge for the Communist Party. The income gap in urban China has widened more than in any other country in Asia over the past 20 years, according to the International Monetary Fund. “The average Chinese person gets angry when he hears about deals where people make hundreds of millions, or even billions of dollars, by trading on political influence,” said Barry Naughton, professor of Chinese economy at the University of California, San Diego, who wasn’t referring to the Xi family specifically. [Ibid]

Xi Jinping and the West

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: Xi’s experience, unusually for a Chinese leader, includes time in the West. Mr Xi spent a short time studying agriculture in the US in 1985. Although Xi isn’t known to have visited his daughter at Harvard, Xi Mingze’s American education adds to Xi’s unusually rich exposure to the U.S., having made up to half a dozen trips to the country. His daughter studies at Harvard. He is seen as more worldly than the dry technocrat he will replace, Hu Jintao. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Though he likes Hollywood flicks about World War II and has a daughter at Harvard University—under an assumed name—he has signaled he may be a staunch Chinese nationalist. Some evidence of a strong nationalist streak emerged recently when he lectured U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta on China’s claim to East China Sea islands held by Japan. “China’s neighbors, including the U.S., should be prepared to see a Chinese government under Xi being more assertive than that under Hu,” said Steve Tsang, director of the China Police Research Institute at Britain’s University of Nottingham. [Ibid]

“His views of the West remain difficult to divine,” Wong and Ansfield wrote in the New York Times. “He once told the American ambassador to China over dinner that he enjoyed Hollywood films about World War II because of the American sense of good and evil, according to diplomatic cables obtained by WikiLeaks. He took a swipe at Zhang Yimou, the renowned Chinese director, saying some Chinese filmmakers neglect values they should promote.” [Ibid]

“But on a visit to Mexico in 2009, when he was defending China’s record in the global financial crisis before an audience of overseas Chinese, he suggested that he was impatient with foreigners wary of China’s new power in the world. ‘some foreigners with full bellies and nothing better to do engage in finger-pointing at us,” he said. “First, China does not export revolution; second, it does not export famine and poverty; and third, it does not mess around with you. So what else is there to say?” [Ibid]

Image Sources: Chinese government (China.org), White House (Biden pictures) and Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021