GYENLO, PLA, AND NYAMBRE VIOLENCE IN LHASA IN 1967

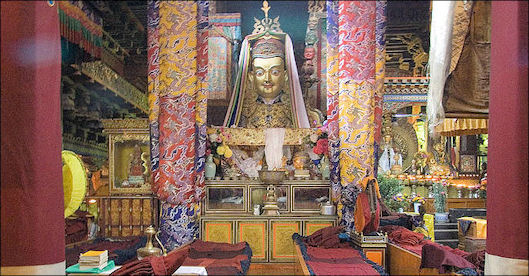

Jokhang Temple in Lhasa

Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “Although weakened by the army’s action, Gyenlo continued to compete with Nyamdre, and factional fighting did not stop in 1967–68. In Lhasa, the western and northern sections of the city came to be controlled by Gyenlo, whereas the center was mostly controlled by Nyamdre. Normal work and life in Lhasa were literally brought to a standstill.

[Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

On events in February 1967, Yin Fatang, the top army leader and Nyamdre supporter wrote: “After getting up on the morning of 10 February, I found that the building housing the cultural workers’ group was almost empty, having only a few persons in it. Later in the lavatory I saw many armed fighters holding rifles and guarding the rear of the assembly hall. At that time I felt it was quite strange because such a sight had never been seen in large compounds in the Military Region. Then, when I went over to the parade ground, it gave me a great shock. There were 72 trucks neatly parked. Armed troops ready to charge with bayoneted rifles were everywhere in front of the meeting hall as well as on the parade ground. A tight cordon was posted around the meeting hall. Not knowing what had happened inside it, I waited outside the hall.

“Suddenly, out of the main entrance came four fighters pushing and pulling a person who, when I got closer, gave me a fright. The person was none other than Comrade Lan Chikui of our Military Region’s combined corps. He was bare-headed with both hands tied behind his back. Then more than ten people rushed up from both sides (they were all members of the headquarters of defending Mao Zedong’s thought), surrounding Comrade Lan Chikui and giving him a savage beating. Some of them pulled his hair, some grabbed him by the neck and some struck his head violently with their pistols. Tens of fists landed on his head like a shower and hit his check and back. In a moment blood flowed straight down his face and he became a mass of flesh and blood. His clothes were torn to pieces and his face was swollen out of human shape. “ ~

This was the beginning of the deep enmity between Gyenlo and the army that would worsen in the next two years. Describing the fighting between the Gyenlo-held People’s Hospital and the Nyamdre-held Potala, a Han eyewitness who was the twelve-year-old son of a surgeon at the People’s Hospital recalled; “Nyamdre shot down into the hospital compound from the buildings on the east side of the Potala, and [those at] the People’s Daily shot at us from that side. They shot guns and fired homemade cannons. My family and I lived in a single-story building near the Potala side, so when I went out I had to run fast across an open area between my building and the hospital’s outer wall, since until I reached the safety of [being close to] the wall, there was a danger of being hit by gunfire coming down from the Potala. On one occasion, when Nyamdre was shooting a lot of homemade cannon shells at the hospital, my mother was so afraid that one of them might hit and collapse the roof of our one-story house and injure me that she took me to stay in the three-story out-patient building, which she felt was safer. I had to sleep on a patient examination table on the first floor. Military control was formalized on 11May 1967,when the Central Committee established the Tibet Autonomous Region Military Control Commission and appointed Zhang Guohua as director, with Ren Rong and Chen Mingyi as deputy directors. All were strongly anti-Gyenlo.” ~

Goldstein wrote: “However, fighting between Gyenlo and Nyamdre continued and actually increased in the second half of 1967. Beginning in 1968, the situation further deteriorated when both factions began to use guns. These were ostensibly stolen from the army, but it appears that in reality supporters in the army turned a blind eye to such “thefts” by revolutionaries, if they didn’t actually aid in them. In addition to acquiring the military guns, the factions also started manufacturing bombs and other weapons in their workshops.

See Separate Articles: CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; FACTIONAL DIVISIONS IN TIBET DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Tibet in the Cultural Revolution “Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution” by Tsering Woeser, Robert Barnett, et al. Amazon.com; “On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969" by Melvyn C. Goldstein , Ben Jiao Amazon.com; About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; Red Guards “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com; Victims and Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution “Victims of the Cultural Revolution: Testimonies of China's Tragedy” by Prof. Youqin Wang Amazon.com; “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin (New York Review Books, 2016) Amazon.com; “Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution” Amazon.com; "Voice from the Whirlwind" by Feng Jicai, a collection of oral histories from the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com ;

Efforts to End the the Cultural Revolution Violence in Tibet

Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “Beijing was concerned about the worsening situation in Lhasa and was eager to restore some semblance of calm there so that it could replace the Regional Party Committee with a new form of government that it called a Revolutionary Committee government. However, before it could do this, both revolutionary factions not only had to stop the violence but also had to agree to the membership of the new Revolutionary Committee government. Consequently, as early as February 1968, at Beijing’s behest, the Military Region Headquarters made an unexpected overture to Gyenlo to this end. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

A leader in Gyenlo recalled this event: On 3 February 1968, the Military Region Headquarters decided to form the (Three-Way) Great Revolutionary Alliance with us. They came to talk with us, carrying the flag of the army. I was very surprised. I didn’t understand why those of the Military Region Headquarters changed their minds in such a short period of time. And even today, I still don’t understand this. Maybe history will give me an answer in the future. Of course, they said that they were sincerely supportive of us and that it was we who denied their support. Although I was the general leader of our faction at that time, I was not able to control the situation, and some Red Guards from Beijing made things worse by verbally attacking Yu Zhiquan, the deputy commander of the military region. He was the one talking with us. Vice-Commander Yu, as a military commander, was not good at debating and almost dozed off at the meeting. Finally, the army men got up and angrily left the meeting, saying that we had humiliated the flag of the army. I didn’t understand why they felt that. However, I knew that things were getting worse, for it was very rare to see the army men come out with their flag and then have the negotiation that day turn out to be such a failure. ~

“As a result of this debacle, Beijing acted quickly and summoned the top leaders of Gyenlo and Nyamdre to Beijing at the end of February for a “study class,” again to end the factional violence. More than three hundred cadres attended, including top leaders such as Tao Changsong of Gyenlo, Liu Shaoming of Nyamdre, and Ren Rong of the Military region. The rationale that leaders in Beijing presented to the delegates was simple. Times have changed, they said. At the beginning of the Great Cultural Revolution, everyone rose up to revolt against the capitalist roaders, but since that time the capitalist-roaders have been exposed. Now is the time to establish revolutionary committees, which are the true tool for creating the dictatorship of the proletariat. Consequently, any further factional conflict would only serve to decentralize revolutionary power and weaken this effort as well as negatively impact Tibet’s war readiness (against India). Thus, the assembled delegates were told that they had to agree to end factionalism, because if it were to continue, the revolution itself would be crippled. However, achieving such an agreement meant bringing about a new positive relationship not only between the two revolutionary factions but also among them, the army, and the cadres. In particular, it meant establishing some agreement about who would hold what positions in the new revolutionary committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region. ~

Goldstein wrote: “On 5May, Zhang Guohua, who was in Beijing, met with the representatives of Gyenlo and Nyamdre and told them that Zhou Enlai had just phoned, instructing that the delegates must send a report on the establishment of the new revolutionary committee within the next two weeks. However, even pressure from this level did not work, because the two factions could not agree to compromise on this committee’s membership. A month later, there was still no agreement, so on 6 June 1968, China’s top leaders, including Zhou Enlai, Jiang Qing, Chen Boda, and Kang Sheng, interviewed the top party committee members of the military region (Ren Rong, Chen Mingyi, Zeng Yongya, Wang Chenghan, Lu Yishan, Liao Buyun, and Yin Fatang) along with others in the Regional Party Committee, instructing them to come to an agreement about the formation of the new revolutionary committee. Their comments were the same as those that Zhang Guohua had made to the representatives of the mass organizations, but they pointedly added that the army should not have been engaged in “supporting one faction and suppressing the other faction.”

PLA Attacks Gyenlo Strongholds

Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “Despite Beijing’s continued pressure to push the representatives to reach an agreement in Beijing, the violent struggle continued in Lhasa throughout the first half of 1968. Gyenlo at this time also pushed to increase its strength outside Lhasa, where the PLA, which they felt tacitly supported Nyamdre, was not stationed in force. As a result, Gyenlo sought to proselytize in the countryside to increase it numbers and power. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

Inside Jokhang

“In the midst of both the chaotic revolutionary violence in Lhasa and the still ongoing study class in Beijing, a signal event took place on 7 June, the day after China’s leaders stated that the PLA should not have supported one faction and suppressed the other. In a major breach of the army’s neutrality, two Gyenlo strongholds in Lhasa—the Jokhang Temple, in the heart of Lhasa, and the Financial Compound, near Gyenlo General Headquarters—were attacked by armed PLA troops. At this time, Gyenlo activists physically occupied the top floor of the Jokhang Temple and had set up loudspeakers on the roof, making it a major platform for Gyenlo propaganda. The Financial Compound also had loudspeakers on its roof. The stream of derogatory and insulting broadcasts emanating from them infuriated Nyamdre and the army, who on 7 June launched a major military strike against both strongholds.” ~

The “attacks on the Financial Compound and the Jokhang resulted in the death of 12 Gyenlo activists, the serious wounding of 13, and less serious injury to another 361. Two soldiers were killed, nine were seriously wounded, and six only slightly injured. One of the heads of Gyenlo talked about the reasons for the attack as well as his role in it: The army was not happy after the 18 January armed struggle,86 in which they failed, and the 3 February [failed army negotiations]. And they considered our attacks on Zhang Guohua as the worst offense, so [I felt] they would seek revenge sooner or later. And they also had failed in other armed struggles, because our side had many workers who were a powerful force in armed struggles. Although [the army] had weapons, they still couldn’t win. You know, sometimes during the fighting their weapons might end up in our hands. [Laughs.] And as I told you, our factories also made weapons. So finally the army decided to do it [attack us], although they still used the name of the Central Committee. At the Jokhang Temple, the broadcast station . . . [t]hey could have just taken the power from us, so why should they shoot at us? At the Jokhang Temple, if I’m not mistaken they killed ten of us. Some of those were shot at the stomach, some in the head, and ten died right away. A few others were injured.”

On why the attacks occurred, he said, “[T]hey said they were there to “take over military control.” . . . Of course, they didn’t like our broadcast station there. They shot at us without hesitation, not just at the Jokhang Temple, but also at the Financial Compound. I was in Beijing then [attending the study class], and Liu Shiyi phoned me immediately when this happened. He asked me what we should do. I stayed cool when hearing this. I said, “Don’t fight back. Let them shoot.” I knew things would be even worse if we fought back. So I told Liu to let the army shoot and that it didn’t matter how many people we lost. Therefore, we lost ten people at the Jokhang Temple and two at the Financial Compound; there was a path linking the Financial Compound to the Second Guest House [the main headquarters of Gyenlo], and the two were killed there. Many others were injured. Ai Xuehua, a photographer, was trying to take pictures as evidence during the shooting and was shot at the back. He didn’t die but was paralyzed.”

“The reason why this happened was that the other faction [Nyamdre] had been losing the game time and time again, and the army decided to help them. Anyhow . . . , we were proud that we properly dealt with the incident. Of course, some of us were very upset when this happened and were ready to fight against the army. I knew it was not right. A few people even suggested bombing the electricity factory in the northern suburb to leave the whole city of Lhasa in darkness. I said that was even more ridiculous, and we couldn’t do it. Liu Shiyi was very nervous when he phoned me and couldn’t even talk in complete sentences. After talking with Liu Shiyi over the phone, I said to the military leaders at the study class that it was not right for them to kill our people. Those leaders pretended not to know anything about it. This attack clearly showed Gyenlo Headquarters that the army was now openly siding with Nyamdre, and, of course, it also put the Gyenlo faction on the defensive. Gyenlo, already at a disadvantage because it possessed fewer guns than its rival, was outraged by this blatant breach of rules by the army, which was supposed to maintain a neutral stance in revolutionary factional disputes, not shoot and bayonet members of the revolutionary masses. The already existing anger and enmity Gyenlo felt toward Nyamdre, the Regional Party Committee, and the army leadership now soared exponentially. However, despite the defeat, Gyenlo’s spirit was not broken, and its members became even more determined to fight back as best they could against their enemies.

PLA Attacks the Gyenlo General Headquarters

The Financial Compound was chosen as the site of the first army attack because of its strategic position, as one of the PLA commanders involved in the attack explained: Before the incident of 7 June, Ding Yongtai told one of his trusted subordinates, “The Financial Compound is the transportation key spot of Gyenlo Headquarters. From there, they can go east to the second command office of Gyenlo, go north to the general office of Gyenlo Headquarters and to the suburbs, and they can also go to the installment team and the experimental primary school. The communications among those units is through the Financial Compound. If the Financial Compound can be captured, Gyenlo Headquarters will be isolated in Lhasa.” [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “ The actual plan of attack was originally based on deceit. Gyenlo Headquarters was to be sent a letter saying several trucks were coming to deliver food, but when the trucks arrived and Gyenlo opened the gate to receive the food, three companies of the 159th Regiment would rush into the compound. If this ruse did not work, the troops were under orders to tear down the compound’s walls. The attack, however, was unsuccessful in spite of the plans.

The following report on the incident details the failure: “The soldiers first broke down the door and tore down the wall around the Financial Compound. They entered from different directions and started to beat members of the Gyenlo Headquarters with wooden sticks and gun butts. Soldiers of the Ninth Company of the 136th Regiment were responsible for capturing the west blockhouse. Soldiers of the First Battalion of the 159th Regiment and the First Company of the 305th Regiment were added to help them. The 136th Regiment started the main attack while the other two companies blocked the masses from coming to join them [Gyenlo]. However, they could not capture the west blockhouse. ~

Shi Banjiao [the top military commander] then ordered Wu Zhihai, the commander of the troops attacking the west blockhouse, to add two squads from the Second Battalion of the 159th Regiment to the fight. These soldiers used implements such as shovels to dig out the doors and windows of the west blockhouse, trying to enter by force. At about noon, when Shi Banjiao called Ding Yongtai asking about the situation at the west blockhouse, Ding said, “The attack at the west blockhouse has not seen any progress yet, and the scaling ladders were all taken by the Gyenlo followers.” Shi Banjiao told Ding, “You seemed like a capable guy, but now you are useless. I put so many soldiers under your control, and you are saying that you cannot get the blockhouse for me.” Shi Banjiao then led an armed platoon of the 138th Regiment to the west blockhouse and started to command the attack himself. [However] [l]ater that day, he was captured by the Gyenlo defenders.

Fighting Near the Gyenlo General Headquarters

A twenty-five-year-old Tibetan PLA soldier who was among those eventually captured by Gyenlo recalled what to him seemed like the “fog of war” that day: The worst incident was] the fight at the Financial Compound. At this time the military headquarters tricked us. . . . They told us to take guns and go to the Financial Compound to fight with some bad elements who were there. . . . When we got there, [Gyenlo] severely beat us up, and we were unable to fire one shot. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

Q: What happened? A: After we got there, they [the military headquarters] ordered us to prepare to shoot. We did this, but the order to open fire never came. A this time the deputy chief of staff was captured by Gyenlo. . . . We learned of this, and that’s why we were sent to attack the Financial Compound. When we arrived there, the company commander was also seized by Gyenlo. And they seized several Tibetan soldiers [including me]. I had a machine gun, which they took and beat me severely. I also had three hundred bullets, which they stole. They ripped my clothes off and left me completely naked. Then they took us to the Military Control Commission Office within the Financial Compound. Actually the Military Control Commission was supposed to stop outbreaks of fighting within the unit. We lost our guns and were taken [into custody], as were our officers. . . . A fat Chinese was there. He said, “Don’t seize the common soldiers, just the officers.” ~

Q: Was it Gyenlo who seized you? A: Yes, it was Gyenlo. That afternoon I didn’t know how the battle at the Tsuglagang (Jokhang) had gone. I had been kicked a lot and was unable to walk well. They were not afraid to do this, even though we were soldiers. Then they suddenly said to us, “You lost your guns; now go back.” Q: How many soldiers were there [captured]? A: More than ten soldiers. All our guns were taken. There were several Tibetans in our group. . . . [We were captured because ] [a]fter we arrived there, we were ordered to lie prone on the ground. Then when the Gyenlo people came running toward us, we never got the order to fire. We just continued to lie there. If we had made our own decision to fire and if people had been killed, it wouldn’t have been good. So the Gyenlo people grabbed our guns and beat us and took us into custody. That afternoon they told us to go, and we left. . . . They sent us back to the military garrison. At the garrison, they asked us where our guns were. When I said they took our guns, the team leader had us all stand in a line and said to me, “You lost the People’s Liberation Army’s weapons.” And then he slapped my face and kicked me. There was nothing I could do but stand there. Then he asked us who stole the guns? I said the revolutionary masses stole them. Then he beat me again because I used the term revolutionary masses. ~

Q: You weren’t allowed to say that? A: At this time we couldn’t call the factions bad people, only revolutionary masses, so I used that term. [But he got angry because I didn’t say bad people had stolen our guns.] They confined all of us who had lost our weapons to the base. They said, “You can’t go outside. If you have work, you have to ask permission to leave.” Then one day the military headquarters held a big meeting. They told us to come. I was very afraid, because I thought they would put me in prison or execute me. However, they gave us new uniforms to put on, and we went. At the meeting they read my name first to stand up. At that moment I thought I would be executed. However, the officers were nice to us. The officer who slapped me now apologized and said, “Don’t be angry with me for slapping you.” Really, it isn’t permitted for an officer to slap an “enlisted” soldier in the army. ~

Q:Were you very afraid? A: There was nothing I could do. I had already lost the gun. So I went up to the platform and was told to sit on the front of the platform facing the audience. Then they praised me a lot. They said, “You suffered a lot of beatings but didn’t fire your weapons. You are really brave men.”

Violence at Jokhang Temple

The Tibetan activist Woeser wrote: “The Jokhang was occupied by “rebels”. The room facing the street to the left on the third floor was used as their broadcasting station; countless “rebels” were stationed there to defend it (most of them were local Red Guards from the resident committee and the factories, there were also some local enthusiasts and Red Guards from Lhasa Middle School). It is said that this broadcasting station was carrying out fierce propaganda campaigns, which is why on June 7, 1968, the PLA, that was supporting the “conservative faction”, attacked the Jokhang with guns, leaving many casualties.[Source: “ Lhasa’s ‘Red Guards Graveyard’ and the Tibetan Cultural Revolution Controversy”, Woeser, August – September, 2013, highpeakspureearth.com ]

“The “Historical Tibetan Communist Party Records of Major Events” published in 1995, described this event in only one sentence: “Troops of the 6th and 7th Lhasa garrison entered the Jokhang that had been occupied by communal organisations but they were obstructed and it came to a conflict with casualties.”

“In fact, during this blood-reeking murder case, 10 people died inside the Jokhang and two were killed in the streets right outside. They were about 20 year old Red Guards from the Hebaling and Banak Shol neighbourhood committees. I heard from people who witnessed the event that back then they could hear the sounds of gunfire: “dadadadada”; and they also heard the broadcasting station giving out the message that “the rebels have been attacked!” The fighting was over very quickly, the number of injured people exceeded those that died; they were randomly thrown onto carriages and transported to the entrance of the Tibetan Hospital.”

PLA Attacks Gyenlo Holed Up in Jokhang Temple

On the same day as the PLA attack on the Financial Compound , later in the afternoon, the more famous of the two army attacks occurred at the Jokhang Temple. A detailed account of the battle follows: “Tang Shengying then gave the soldiers of the Fifth Company a case of bullets and six rocket shells, and Ding Yongtai encouraged them to occupy the commanding spots of the Dazhao Temple and seize the weapons that the masses of Gyenlo’s Fourth Headquarters were keeping there. Soldiers of the Fifth Company then ran [from the Financial Compound] to the Dazhao Temple, ready to start the fight against the Fourth Headquarters of Gyenlo. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

“The Third Machine Gun Company and the Eighth Company went to the third floor from the connecting bridge in the north. One group of the Second Machine Gun Company and the Seventh Company took the stairs in the northeast corner to the top of the third floor. The military signal was “two whistles.” Five veterans guarded the stairs and the door to the second floor. The Fourth Company guarded the door of the Dazhao Temple. The Second Platoon was the backup force. Soldiers were told to tie a piece of white cloth or a white towel to their right arms in order to look different from the masses. ~

“At 6:30 p.m., the soldiers started the fight. Before they started, the commander of the Third Platoon, Shao Guoqing, gave a brief speech. He said, “We have to capture the weapons the masses of Gyenlo Headquarters are keeping, but do not fire without my command. When the fight begins, we will try to assemble at the southwest corner. Do not fire submachine guns from a long distance. You can use machine guns, but do not use more than ten bullets.” The soldiers set off with their bayonets attached and pointing outward. They shouted, “Kill! Kill!” [and] “Lay down your guns and we will spare your lives.” At that time more than sixty persons from Gyenlo’s Fourth Headquarters were having dinner and studying in the corridor. ~

“All these people, with the exception of one person who was at the broadcast station, stood up when they heard the noise. They surrounded the armed soldiers, some of them waving the red book, some holding rakes. They shouted, “Long live Chairman Mao! Long live the Communist Party!” A few people pointed to their chests, shouting bravely, “Shoot me. Shoot me.” The person at the broadcast unit then started broadcasting “Emergency! Emergency!” through the loudspeakers. Hearing that, the commander of the Third Platoon jumped to the platform and fired two shots into the air. The soldiers of each platoon then started to shoot at the members of Gyenlo Headquarters on the third and fourth floors with semiautomatic rifles, submachine guns, and cannons. Some soldiers of the Second Platoon went upstairs and shot from there into the revolutionary masses. Five veterans shot at the loudspeakers on the fourth floor. The gun battle lasted about two minutes. Three loudspeakers were destroyed, and sixty people of Gyenlo were killed or injured. Six soldiers were also killed or injured. More than one thousand bullets and nine hand grenades were used by the soldiers. The soldiers captured one semiautomatic rifle and some guns and hand grenades from the masses.”

A Gyenlo member who was just outside the Jokhang saw the attack start and remembered: “Those people went inside the Jokhang through the Shingra entrance, the place that was used for keeping firewood during the Mönlam Festival. Before that, the woman who was broadcasting from the roof of the Jokhang was shouting, “This is the red rebellion broadcast station.” . . . After those people went inside the Jokhang, no voice came from the broadcast station. Probably, they seized that woman.At that point, I didn’t dare to go inside. Some people who had gone inside were saying, “You shouldn’t go inside, because when we went inside the people in the Jokhang had burned lice insecticide, and we felt that we were almost going to die from the fumes.” So I didn’t go inside, and I didn’t see anything. Then I went home.” ~

Another Gyenlo fighter who was part of the group in the Jokhang recalled: “I was not in the Jokhang that morning. It was a fortunate coincidence that I had gone home. Otherwise I would have been killed. I heard that the soldiers climbed up to the temple of Lhamo and first shot a gun into the sky. Then they started shooting machine guns. At that point, a girl called Tshamla was shot in the forehead, with the bullet coming out of the back of her head. And there was a boy called Sonam. First his leg was shot, and he fell down. Then the soldiers stabbed him with their bayonets. I had a friend called Kejöla; he was shot twelve or thirteen times. His whole body was riddled with bullets. All together, they killed twelve people in the Jokhang. Then the rest of the people were locked up in the Shingra that night...The next morning, the rest of the people [who had been injured from beatings with rifle butts] were made to pull a cart and take away the corpses.” ~

Nyamdre Attacks Gyenlo in Jokhang Temple with Insecticide

The attack also involved Nyamdre fighters, one of whom recalled that the Nyamdre side also fought with insecticides: At that time, they gave us the powder for killing lice. . . . [W]e were staying in the compound of the People’s Government of the Autonomous Region. We were not in our work unit. In those days there was a broadcast station in the Jokhang that was said to be very powerful. So probably they told us that we had to take over that broadcast station. We were given only the powder for killing lice. We didn’t have other weapons. The insecticide was put in plastic. I remember I put that in my pocket. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

“That night, when we climbed up a ladder, they [people in the Jokhang] stoned us. It was just like in the movies of the [early] Chinese Empire, where the people were stoned when they climbed up ladders to scale the walls of a fortress. That night . . . a lot of people were there. They climbed up to the place where the broadcast set was located. I reached the place where the loudspeaker was set up.There were not many people from Gyenlo. They were hiding, covering their heads with their hands. Some people threw the insecticide at those who were hiding. I told somebody, “Don’t throw that at the people who are not doing anything. Why are you throwing that at those people? You have to throw it at the people who are fighting.” I just threw some insecticide [at the people who were throwing stones at us] when I was climbing up. Otherwise, I didn’t get any chance to throw it. I thought it would be useless to throw it at the people who were hiding. Later, Nyamdre seized those [Gyenlo] people and brought them down. I didn’t know where they took them. There were men and women; there were not many people. At that point Nyamdre had many more people.

Q: How many hours did they fight? A: They didn’t fight very long. After we gathered together and were brought to the Jokhang, we had to wait in the courtyard for about an hour or half an hour. After that we started to climbed upstairs. The [Gyenlo] people who were on the roof of Jokhang were all seized. Later, we went back to the People’s Government compound.

Aftermath of the Attack at Jokhang Temple

The Tibetan activitst Woeser wrote: This event at the Jokhang caused a storm of protest in Lhasa, it even affected Beijing. Mao Zedong and Lin Biao criticised the local officials for this action, condemning the military for “supporting one faction, but suppressing the other”. Respective officials of the Tibetan military apologised to the “rebel faction”, some were even punished. The “rebels” gave a detailed report on the event in the “Red Rebel Magazine” and even made a badge showing Mao Zedong criticising the local officials. They also held large-scale demonstrations and the deceased were pompously buried in the “Martyrs Graveyard” in Lhasa, where they established a small park especially for them. [Source: “ Lhasa’s ‘Red Guards Graveyard’ and the Tibetan Cultural Revolution Controversy”, Woeser, August – September, 2013, highpeakspureearth.com ]

”Initially, the deceased were recognised as martyrs, but one year later they were dismissed as people whose “death cannot wipe out their crimes”. Their coffins were dug up and their bodies were ruthlessly left outside. The husband of an injured broadcaster said when interviewed by me: “Back then, when I went to the graveyard to have a look, five or six graves had already been opened, the bodies were rotten to the bones, maggot-eaten with flies buzzing around them. A few bodies were later reclaimed by the respective families; the remaining ones were buried again. Tibetans never had the tradition of burying the dead, but we had to do it like that back then because they were said to be martyrs. But in the end, they were still treated in such a devastating way…” He choked, he could not continue his story.

Ending of Cultural Revolution Fighting in Lhasa

Melvyn Goldstein wrote: “Ironically, a few days after the killings, on 12 June 1968, an agreement between the factions was actually signed in Beijing by the participating delegates, who were still there at the study class. In theory the agreement ended the factional conflict, saying, “Both sides guarantee that [henceforth] there will be no violence of any kind. Shooting guns and cannons will cease, and in the future both sides must not instigate violence or participate in violence on any pretext.” However, not surprisingly, the agreement was ignored once the Gyenlo leaders returned to Lhasa. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup,“ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

“ However, not surprisingly, the agreement was ignored once the Gyenlo leaders returned to Lhasa. In the ensuing months, the situation in Lhasa worsened substantially, and the central government convened another meeting in Beijing in late August 1968, at which the leaders of Gyenlo and Nyamdre were to meet the very top leaders of the central government and the Central Great Cultural Revolution Group, resolve the factional conflict, and agree to work together under the new Revolutionary Committee. On 26 August in Beijing, the top leaders questioned the Gyenlo and Nyamdre representatives closely, and Premier Zhou Enlai tried to mollify Gyenlo by saying, “It was wrong to send in the army on 7 June. It was not approved by the Central Committee, and the Standing Committee of the Military Region has admitted its mistake.” At the same meeting, a strong self-criticism written by the Party Committee of the Tibet Military Region was passed out, and the Gyenlo and Nyamdre representatives were told to read it overnight and discuss it the next morning. Addressed to the top leaders in China, it is a remarkably frank statement intended to placate Gyenlo, illustrating how intently Beijing wanted to settle the conflict.

“The Written Self-Criticism on the Mistakes Made by the Standing Committee of the Party Committee of the Tibet Military Region Regarding the Work of Supporting the Left” to: Chairman Mao, Vice-Chairman Lin, the Central Committee, the Central Military Commission, and the Central Great Cultural Revolution Group read: “Since we joined the local Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, our PLA who are stationed in Tibet did a lot of work in the campaign of the “three supports” and “two troops,” using the guidance of Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line and the wise leadership and intimate care given by Chairman Mao, Vice-Chairman Lin, the Central Committee, the Central Military Commission, and the Central Great Cultural Revolution Group and the vigorous support and help of the broad revolutionary masses and the revolutionary young militants and cadres. We complied with the great leader Chairman Mao’s call to fight, which was, “The PLA should support the masses of the left.”

“However, we still made a lot of mistakes in the work of supporting the left, because the members of our Standing Committee of the Party Committee of the Tibet Military Region did not fully understand the revolutionary line of Chairman Mao and did not carry it out completely. The main mistakes we made were that we “supported one group and suppressed the other group” and “were close to one group and estranged from the other group.”

“We mistakenly regarded the revolutionary mass organization Gyenlo Headquarters as the bad organization controlled by “a handful of counterrevolutionary elements.” We severely attacked and suppressed this organization. We arrested and interned some persons in charge, some members of the revolutionary masses, some revolutionary young militants, and revolutionary cadres of this organization. Some of them were suppressed as “counterrevolutionary elements.”We seriously dampened their revolutionary enthusiasm. At the same time, we made a series of mistakes in propagandizing inside and outside the army. We also put political labels on this organization, such as “antiparty, antisocialism, and anti–Mao Zedong thought.” We did wrong deeds that were meant to disintegrate this organization...

“The [Jokhang] incident of 7 June did not happen by chance. It was our fault that it happened. It completely exposed our uncorrected mistakes of supporting one group and suppressing the other and being close to one group and estranged from the other. It completely exposed our lack of discipline. It happened because we did not correctly deal with the revolutionary masses of Gyenlo Headquarters. It was also the consequence of our failure to fulfill the instructions concerning the struggles between two lines in the troops. After the incident of 7 June happened, we did not recognize the gravity of our mistake. We did not deal with it very seriously. And that was more serious. . . . We, the leaders of the Military Region are responsible for the mistakes above. The broad commanders and soldiers have no responsibility.

“The main reason we made mistakes in the work of supporting the left is that we did not grasp the essence of the works written by Chairman Mao. And we did not apply them very well. We did not understand well the revolutionary line of Chairman Mao. And we did not adhere to the important instructions of Chairman Mao, the Central Committee, and the Central Cultural Revolution Group. We thought that the 26 February telegram sent by the Central Cultural Revolution Group to Gyenlo Headquarters was just a telegram to the revolutionary masses and did not pay attention and study it. Consequently, we did not correct our mistakes in time. We did not learn well about the important instructions, such as [those issued on] 18 September last year and 6 June this year by the leaders of the Central Committee and the Central Cultural Revolution Group. We did not understand them completely and did not implement them well. In addition, we were not united in our understanding of these documents...

“Our mistake is serious. The lesson is heavy. We did not accomplish the honorable mission given us by Chairman Mao. We are unworthy of the instruction and trust of our great leaders Chairman Mao and Vice-Chairman Lin. And we disappointed the trust and the expectations of the broad revolutionary masses. We are very sorry about that. We apologize to Chairman Mao and Vice-Chairman Lin. We apologize to the Central Committee and the Central Cultural Revolution Group. We apologize to all revolutionary masses.

Goldstein wrote: “With this statement in hand, the Gyenlo leaders in Beijing had no choice but to say they would end the fighting and agree to the membership composition of the Revolutionary Committee. Consequently, on 5 September 1968, the TAR’s Revolutionary Committee was formally established, with both factions and the army agreeing to cease all fighting.

Tensions After Cultural Revolution Fighting Ended in Lhasa

However, in Lhasa, the animosity still ran deep, and the conflict did not end. One Nyamdre delegate and his wife recalled what happened when they returned to Lhasa from Beijing: Husband: “After we returned [from Beijing] they said there should be no factions and ideologies. . . . We went to speak to the members of Nyamdre and Gyenlo. I said you must come together, and we told them about the instructions from the leaders in Beijing. . . . We went from Beijing to Lhasa by airplane. When we arrived in Lhasa many people from both factions were waiting to welcome us back. They took us immediately to the military headquarters. I didn’t even go home first. However, after we entered the gate of the military headquarters, the two factions started fighting. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, “ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

Wife: “It couldn’t be stopped. When they [the delegates] first came back to Lhasa, [representatives from] all the offices and the masses were sent to welcome them in front of the Potala. We got up early to go, but they didn’t arrive until noon. So we waited. Nyamdre and Gyenlo sat separately, singing songs back and forth, each side trying to sing more loudly than the other. The offices brought along drums and cymbals, and the two factions put their drums and cymbals together and banged them loudly. They [the delegates from Beijing] arrived at noon. We welcomed them, and then they left. At the time, the two factions were supposed to leave and go back to their factories. But they [the delegates] weren’t even in the military headquarters when we started fighting. People took the flags and put them on their waists and starting fighting with the flag poles. At the same time, in rural counties like Nyemo, the factional conflict escalated when Gyenlo, outnumbered in Lhasa, moved to gain control of the countryside, where only a few troops were stationed. “

After that the conflict moved the countryside of Tibet. See Melvyn Goldstein, “ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009. The above information is from Chapter 1. In chapter 2, the plans to mobilize the Nyemo peasant masses in 1968 are examined.

Image Sources: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org, New York Times, Woeser, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated July 2015