ENEMIES IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

In an attempt to rehabilitate and boost his popularity, Mao launched attacks on his enemies in the Communist Party during the Cultural Revolution. In ways this was the primary purpose of the Cultural Revolution. Those attacks were extended beyond the government to include intellectuals, teachers, and scientists, many of whom were sent to work camps in the countryside for "reeducation." Others were killed in various ways. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

In an attempt to rehabilitate and boost his popularity, Mao launched attacks on his enemies in the Communist Party during the Cultural Revolution. In ways this was the primary purpose of the Cultural Revolution. Those attacks were extended beyond the government to include intellectuals, teachers, and scientists, many of whom were sent to work camps in the countryside for "reeducation." Others were killed in various ways. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Mao singled out nine categories of enemies: landlords, rich peasants, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements, rightists, traitors, foreign agents, capitalist roaders and — the Stinking Ninth — intellectuals. In the fight against "class enemies" and "bourgeois reactionaries," teachers, people with a college degree or relatives overseas, workers, and members of minority groups such as Tibetans, were all targeted.Mao announced that the Cultural Revolution would “thoroughly expose the reactionary bourgeois stand of those...who oppose the party and socialism.” Children of landowners were thrown into trash cans. Families who lived in large houses where squeezed into single rooms as their possessions were smashed by Red Guards and poor families moved into the other rooms. Families that held on to their deeds were later able to reclaim their entire houses. Many however handed over their deeds to the government in effort to avert further persecution.

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Across China teachers, former landlords and intellectuals were being humiliated, beaten and murdered. They were hounded by neighbours, colleagues and pupils moved by misguided revolutionary fervour, personal grudges or little more than whim. Friends, children and spouses turned on them. In Chongqing, rival factions battled with guns and tanks. In Guangxi, there are accounts of cannibalism. Victims were condemned as "monsters and freaks" By the time the chaos subsided 10 years later, an estimated 36 million had been persecuted and at least 750,000 were dead in the countryside alone. Red Guards had smashed up temples, burned books and destroyed historical treasures. Universities had closed and pupils missed years of schooling. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; REVOLUTIONARY ENTHUSIASM, MANGOES AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE, ATTACKS, MURDERS AND PROMINENT VICTIMS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; HORRORS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Victims and Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution “Victims of the Cultural Revolution: Testimonies of China's Tragedy” by Prof. Youqin Wang Amazon.com; “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin (New York Review Books, 2016) Amazon.com; “Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao's China” by Lian Xi Amazon.com ; “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su Amazon.com; “The Execution of Mayor Yin and Other Stories from the Great Cultural Revolution” by Chen Jo-his Amazon.com; “Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of the Cultural Revolution” Amazon.com; "Voice from the Whirlwind" by Feng Jicai, a collection of oral histories from the Cultural Revolution Amazon.com; About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com

Evolution of Violence During the Cultural Revolution

According to Associated Press: Mao Zedong began the Cultural Revolution “by purging officials considered insufficiently loyal. Over its course longstanding party officials, intellectuals and teachers came under violent attack, while traditional Chinese thought and culture were condemned along with foreign influences. The violence largely abated in 1968 when the People's Liberation Army was brought in to impose order, but normal government functions were not restored until after Mao's death in September 1976. [Source: Associated Press, June 2, 2016]

According to a commentary in Parlio.com: “Mao urged youngsters to rebel against the authorities but counseled (via his wife) “attack with words and defend with force” (wengong wuwei). The Red Guards began their offensives with the so-called “big character posters” and mass debates. But all too quickly, these verbal battles degenerated into violent skirmishes, sometimes with weapons pilfered from militia organizations and even the military. Why did these ardent apostles of Mao so readily ignore his dictum? Because once you make yourself invulnerable with conviction and force, it’s hard to put up with disagreements and criticisms. And you don’t have to either—you can simply compel agreement, compliance, or acquiescence through force. And in the process you also get a kick out of the subjugation of another will and the attendant exultation of mastery. [Source: Parlio.com]

“The political campaigns that armed individual Chinese citizens with “the spiritual atom bomb of Mao Zedong Thought” and the license to violence only ended up rendering everyone vulnerable, breaking up families and communities by sowing apprehension, suspicion, mistrust and fear. As atomization took hold, institutions crumbled, society disintegrated, and the powers that be (Mao and his co-instigators of the Cultural Revolution) grew more autocratic.”

Hundreds of thousands of people were killed as the country fell into what Dikotter describes as civil war, with different Red Guard and People's Liberation Army (PLA) factions fighting each other, and millions more were displaced and traumatized as society broke down around them. [Source: James Griffiths, CNN, May 13, 2016 /^]

Cultural Revolution Attacks Take On a Life of Their Own

People were accused of being class enemies for doing the simplest of things: forgetting a slogan from "The Little Red Book", wearing Western clothes, seeking repayment of a debt or hoarding a piece of meat. Entire schools of elite musicians and teams of athletes were sent to labor camps. Intellectuals were kept in prisons called cow sheds.The only time they saw their spouses was during annual conjugal visits. Peasants deemed “antisocial” were forced to stand for hours with their heads in the kowtow position, begging for forgiveness. Senior officials had their heads shaved, dirty gloves stuffed on their mouths, and ink and paint splashed on their faces. They were often forced to stand, bowing, with insulting signs hung from their necks.

Yiching Wu told the Los Angeles Review of Books: The” issue of how ordinary people were provided with political repertoires to be acted on helps account for the characteristically dispersed and explosive character of the Cultural Revolution. While the rebels looked to the Maoist leadership for political guidance, the relationships between Mao and those who responded to his call were tenuous and fragile. With the breakdown of the party hierarchy, political messages transmitted from above were interpreted in different ways by different agents. People responded to their own immediate circumstances, giving expression to a myriad of social grievances and antagonisms. The forces unleashed by Mao took on lives of their own.” [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook,Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016 ~]

Many hostile acts were taken by attackers seeking revenge, avenging a grudge or acting out of jealousy. People could make trouble for neighbors they resented for some reason or another by spreading rumors about them. If someone was jealous about another’s Flying Pigeon bicycle he could make a few comments about “bourgeois tendencies” to local units of Red Guards. Professor Suzanne Weigelin-Schwiedrzik of the University of Vienna who was in China during the early 1970s as a student that by then everyone was nervous. The targets of struggle had shifted so often and yesterday’s accusers had become today’s accused so many times that everyone knew it could be them next.

Crackdown on Intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution

In the Cultural Revolution, learning was a crime. The crackdown on teachers, professors and intellectuals was particularly nasty. In middle schools students ordered their teachers to cultivate cabbage. In high schools, teachers wore dunce caps and spent the whole day reciting "I am a cow demon" in front of classroom filled with mocking students.

At Fudan University in Shanghai, a woman professor was crippled for life after she was beaten and kicked for "advocating the reading of the bourgeois feudalist William Shakespeare." The dissident Wang Xizhe said he had to perform a "grotesque loyalty dance" and offer "morning prayers and evening penitence" for his perceived crimes.

Describing the treatment he endured in the Cultural Revolution, one linguist told The New Yorker, “They shaved off half our hair — hat was called the Yin-Yang Head. Then they took off their leather belts and started beating us. First they used the leather, then the buckle. One was wearing a white shirt, it turned entirely red with blood. Once they let me go, I telephoned my work unit, and they sent people to take me back home.”

"In China," Theroux wrote, "an intellectual is usually just someone who does not do manual labor...It was an awful fate but it was easy to imagine how the policy had come about. Everyone in his life has wished at one time or another for someone he disliked to be trundled off to shovel shit — especially an uppity person who had never gotten his hands dirty. Mao carried this satisfying fantasy to its nasty limit."

Struggle Sessions during the Cultural Revolution

Many people suffered through humiliating "struggle sessions" in which they were taunted and ridiculed for days by members of the Red Guard. Describing such an event, a former university professor told Theroux, "One night, in September 1966, Red Guards showed up at my house. Forty of them. They came inside — they burst in, and there were both men and women. They put me on trial so to speak. We had 'struggle sessions.' They criticized me...They stayed in my house, all of them, for forty-one days, and all this time they were haranguing me and interrogating me. In the end they found me guilty of being a bourgeois reactionary. That was the crime...I was sent to prison...I had no idea when I would be released. That was the worst of it."

Describing an assault on a landlord labeled "The Capitalist" one former member of the Red Guard told Theroux: The Red Guards "decided to criticize The Capitalist. There were about eight or nine of us following them — we were just little kids. We made a paper dunce cap for The Capitalist. His name was Zhang. We went into his house pushed the door open without knocking. He was in bed. He was very sick. He had stomach cancer. We shouted at him. We made him confess to his crimes. We renounced him. We forced him to lower his head so that we could put on the dunce cap — lowering the head was a sort of submission to the will of the people."

"He had cancer," he continued. "He could not walk. We mocked him in his bed. Then the neighbors came in. They also accused him — but not of being a capitalist. I remember one woman shouted, 'You borrowed cooking pots and materials and never gave them back!...On one of his chairs there was a tiny emblem of the Kuomintang. That proved he was a capitalist and a spy. Everyone was glad of that. We screamed at him, 'Enemy! Enemy!' He died soon after that."

Prisons and Humiliating Jobs during the Cultural Revolution

Communists officials labeled as "enemies" were sent to labor camps like the May 17th Cadre Schools, which resembled a Stalin-era Siberian gulag. A former history professor told Theroux, "I was in prison, from 1966 to 1972. But I tell my friends I was not really in prison for six years. I was in for three years — because every night when it was dark and I slept, I dreamed of my boyhood, my friends, the summer weather, and my household, the flowers, the birds, the books I had read, and all the pleasures. So that it was only when I woke up that I was back in prison."

"Usually we got one thin slice of meat a week," the professor continued. "If the wind was strong it blew away. But just before President Nixon's visit we started to get three pieces. The prison guards were afraid that he might visit and ask how they were being treated."

Many prominent intellectuals were sent to remote provinces such as Qinghai, Ningxia, Gansu and Inner Mongolia to perform manual labor. There a Russian instructor carried boulders; a math professors was punished for not fulfilling his brick quotas of 900 bricks a month; and a journalist was told everyday to write six-page essays on "Why I Like Dickens," only to be told afterwards it was rubbish and to write six more pages.

Some intellectuals were imprisoned in "cowsheds," outhouses that were turned into makeshift prisons. The president of prestigious Fudan University in Shanghai was forced to assemble radios in the day and study Mao sayings at night. A banker was forced to work as flycatcher and keep the dead flies in box. After counting the flies in his box his Red Guard supervisor told him, "125 isn't good enough, kill some more."

Losing Your Father to the Cultural Revolution

Carol Chow only knew her father for a few months before he was taken away. Zhou Ximeng killed himself in captivity, aged 27. "It's painted like a memory. It's like he's frozen in that time," she told The Guardian . She knows her father from a handful of photographs and from the stories her mother has told, of a smart, confident, capable man — too accomplished, perhaps. "My mother said he was an overachiever.," Chow says. "Whatever he did, he excelled at — he was always top of his class. The reason she gave for his suicide was that he had never encountered any huge obstacles. I think he reached a point where it was all beyond his control and he didn't feel he could change anything. You had to first renounce yourself and then renounce your family and friends. I think, when he got to that point, really, he just closed up." [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

Zhou came from a long line of landowners and scholars; his father, a renowned paleontologist, had spent time in America and Taiwan. But in the Cultural Revolution such a privileged pedigree condemned him. All it took was "some really small comment" for him to be seized and held, in a village outside Beijing. His body lies somewhere near the train tracks where he died. Her father was subsequently forgiven "for his crimes, whatever they were", she says. "I don't feel bitter or angry —I feel sad for him, that he missed so much," adds Chow, now 42, and who has two daughters.

Widow of a Famous Architect Recalls the Cultural Revolution

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “When Liang Sicheng was denounced as a counter-revolutionary, he was scared to look even his wife in the eye. Lin Zhu, who had been working in the countryside at the time, rushed home to him on learning the news. "He said, 'I've been waiting for you and missing you every day, but I'm afraid to see you,' " the 83-year-old told The Guardian. Her husband sensed the horror ahead. Beijing's Tsinghua University — one of the country's top institutions — was already covered in posters attacking professors. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

Liang Sicheng is regarded as the father of modern Chinese architecture. Lin Zhu is his widow. "Back then, I thought this was like a dark cloud that would soon pass. I didn't realise it would cover the country for the next 10 years," Lin says. When it lifted, Liang was dead, his health wrecked by the scores of lengthy "struggle sessions" publicly to humiliate him; by beatings from Red Guards; and by the cold, damp conditions of the building to which the family had been moved.

Lin still struggles to understand how hundreds of millions could participate in such cruelties. Some of Liang's persecutors were forced into taking part, she says; others were jealous of his success. Most were young students who did not understand his ideas. To her husband, who had loved teaching, that was particularly painful. "He wrote confession letters, one after another, but didn't know what he had done. The most important claim was that he had received a 'capitalist education'. No one could tell us what proletarian architectural design was — and you were too afraid to ask."

As the movement escalated, Lin considered demands to join it: "I thought probably I would be beaten to death by the Red Guards. Maybe my children would desert me and my friends would keep their distance. But I couldn't understand what Liang Sicheng had done. I couldn't go against my conscience by leaving him."

Together they endured six years of enforced Maoist study and public denunciations that often ran for hours. "Because it was all day long, the brain sort of became numb," Lin recalls. "Normally he was not beaten up at those sessions, but sometimes they would come and beat us at home." Liang's ordeal ended when he grew so sick that he could no longer rise from his bed for the struggle sessions. He died in 1972, aged 70.

In later years, Lin worked with her husband's accusers; some, quietly, apologised. She does not blame individuals for caving into pressure to attack others, though she is adamant that she never did so. She even suggests those years helped her to grow. "Whatever happens, whatever comes, I'm not afraid any more. It made me stronger and made me think," she says. But she fears that intellectual life in China has never fully recovered — and she worries the country could see another such movement. "Many of us are concerned about whether we can avoid a similar disaster in future. History doesn't repeat itself exactly — but it's possible."

Family Broken Up By Guilt from the Cultural Revolution

John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Zhang Hongbing “was raised as an "official's kid," not a farmer. His father headed the county health department. Zhang's mother was a hospital administrator. Both were People's Liberation Army veterans and Communist Party members... Zhang, along with his older sister, joined the Red Guard youth paramilitary movement at the outset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Zhang's given name was Tiefu, but at 13 he was so excited about the Revolution that he changed it to Hongbing (literally, "red soldier"). "My parents agreed, and not only that, they were really happy," he recalled. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2013]

“Yet by year's end, the Cultural Revolution had begun pulling his family apart. Zhang's older sister contracted meningitis in dirty travel facilities while going to Beijing to hear Mao speak at a rally. She died in December 1966 at the age of 14. Zhang's father, meanwhile, was subjected to "criticism and struggle sessions" by his colleagues and by the Red Guard. At that stage, Mao's faction in Beijing encouraged Chinese youths and party members to abuse and humiliate authority figures, especially those suspected of sympathy with Mao's rivals.

"I didn't beat my father, but I was at the sessions," Zhang said. "I might have been yelling, I don't remember." Zhang's mother, Fang Zhongmou, also underwent two years of criticism sessions. In an album of Cultural Revolution memorabilia stashed among his office files, Zhang keeps a tiny sepia snapshot of his mother and father, wearing dunces' caps, on a forced march through town.

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Then the Cultural Revolution burst into their lives. In the streets of Guzhen, Red Guards smashed heirlooms and burned books: "I thought it was great – an unprecedented moment in history," Zhang said. In a blaze of enthusiasm, the children changed their names. Zhang, previously called Tiefu, became Hongbing, or "red soldier". His elder sister joined millions of Red Guards trekking to Beijing to see Mao. But shortly after her return, she collapsed and died from meningitis, aged 16. Months later, their father was attacked as a "capitalist roader" in at least 18 "struggle sessions" of verbal and physical abuse."I wrote a big character poster about him; I just wanted to follow Chairman Mao," said Zhang. "For a child to criticise their parents wasn't just our household. The whole country was doing it." [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, March 27, 2013 ////]

"My mother, father and I were all devoured by the Cultural Revolution," Zhan told The Guardian. "[It] was a catastrophe suffered by the Chinese nation. We must remember this painful historical lesson and never let it happen again." A family photo records his father being paraded in a dunce's cap. Another shows crudely pencilled illustrations of their story, from an exhibition that lauded Zhang's fervour. In the last sketch, blood spurts from his mother's mouth as she is executed. The family was once "harmonious, happy and warm", said the lawyer. ////

His mother Fang was only 44 when she died. She was bold, extrovert and honest in all dealings, recalled her younger brother, Meikai. "When I talk about her, I want to cry," he said. "From the age of three I would follow her around; she was like another mother." She met her husband when they joined the revolutionary cause, but their life was scarred by politics from the first. Her father was executed as a suspected Nationalist agent; Zhang blames a personal grudge. Later, as they struggled to survive the Great Famine, Zhang's younger brother was sent away to a relative who could feed him. ///

Son Helps Send His Mother to a Firing Squad During from the Cultural Revolution

John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Zhang said his mother was vulnerable because her own father had been executed in 1951 as a landlord, a bandit, and a spy. The accusations were made, without proof, he said, during an anti-landlord campaign launched by the Communist Party shortly after its 1949 victory in the civil war. With a "counter-revolutionary" family background, Fang was barred from entering the Party in the early 1950s, and then became a prime target for criticism sessions years later. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2013]

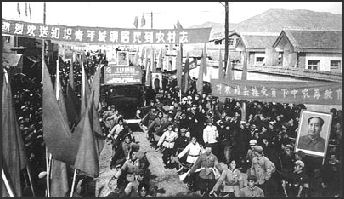

Young Red Guards

“Having suffered the loss of her daughter and years of violent criticism sessions, Fang Zhongmou finally snapped one evening in 1970. "Why is Mao creating a cult of personality?" she asked her husband and son. She threatened to tear down portraits of Mao in their house, and she suggested that China should posthumously rehabilitate Liu Shaoqi, a leading politician whom Mao had imprisoned and who died in custody in 1969.

“Zhang was horrified, as was his father. "If you attack our dearest leader Mao Tse-tung, you'll get your dog's head crushed!" Zhang told his mother, according to testimony he filed to the military court investigating his mother, and retrieved from the Beijing National Library in 2009. When his mother refused to take back her words, the young Zhang denounced her in a note he placed under the door of an army officer who lived nearby. Zhang's father, meanwhile, fetched the military police unit charged with law enforcement in Guzhen during the Cultural Revolution. In fury, Fang locked herself in a room and set fire to a portrait of Mao. Her husband ordered her out of the room and instructed his son to beat her. Zhang complied, striking her on the back with his fists. A soldier brought in by Zhang's father then struck her and took her away.

County records show that Zhang's mother was found guilty of "attacking Chairman Mao Tse-tung" and executed on April 11, 1970. Zhang watched her at a mass tribunal in town that day, but did not follow her to the firing squad two hundred yards away. His father had divorced her days before the execution. Since then, Zhang says, he has suffered from depression and has been tormented by thoughts that he violated the ancient Chinese code of filial piety. "I abandoned my family, I stomped on them!" Zhang said. "Killing or abusing a parent in the Tang Dynasty was called 'the heinous crime.' You'd be killed!"

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “In 1968, Fang fell under suspicion due to her father. Two years of investigation, detention and uncertainty tormented her: "Why don't they just make a decision on me?" she asked. "Her father's death, her husband's persecution, her daughter's death – everything that happened made her suspicious of the Cultural Revolution … She was sick of [it]," said Zhang. Eventually conditions improved and she was allowed to sleep at home. Then, one evening, her zealous son accused her of tacitly criticising Mao. The family row spiralled rapidly: Zhang said, “Ifelt this wasn't my mother. This wasn't a person. She suddenly became a monster … She had become a class enemy and opened her bloody mouth." [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, March 27, 2013////]

Fang's brother begged her to take her words back, warning she would be killed. "I'm not scared," Fang replied. She tore down and burned Mao's picture. When her husband and son ran to denounce her, "I understood it meant death," Zhang said. In fact, he added, he called for her to be shot as a counter-revolutionary. He last saw her as she knelt on stage in the hours before her death...They beat her, bound her and led her from home. She knelt before the crowds as they denounced her. Then they loaded her on to a truck, drove her to the outskirts of town and shot her. ////

Fang's brother begged her to take her words back, warning she would be killed. "I'm not scared," Fang replied. She tore down and burned Mao's picture. When her husband and son ran to denounce her, "I understood it meant death," Zhang said. In fact, he added, he called for her to be shot as a counter-revolutionary. He last saw her as she knelt on stage in the hours before her death...They beat her, bound her and led her from home. She knelt before the crowds as they denounced her. Then they loaded her on to a truck, drove her to the outskirts of town and shot her. ////

“Most children who turned on their parents were under political pressure, said Yin Hongbiao, a Beijing-based historian. "Those with 'bad parents' suffered a lot and they resented their parents instead of resenting the system which brainwashed them daily," added Michel Bonnin, of Tsinghua University. "They were encouraged to denounce their parents, so as to 'draw a line' between them and the enemy. It was the only way to save themselves. There were many cases of children who tried to protect their parents against the violence of Red Guards and were then beaten or even executed." Zhang's case is much more unusual, but Schoenhals suggested timing was critical: early 1970 saw a harsh campaign against counter-revolutionary activities, known as one-strike and three-anti. "You could come across anything if you had 700 million people embroiled in a conflict of this seriousness and magnitude," he added. ////

Academic Attacked During the Cultural Revolution

In a review of “The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Ji Xianlin, Zha Jianying wrote in the New York Review of Books: “Like other ordinary Chinese, Ji had no idea what the Cultural Revolution was all about when Mao Zedong launched it in 1966. Son of an impoverished rural family in Shandong, Ji had managed, through diligence and scholarship, to get a solid, cosmopolitan education in republican China. Having spent a decade in Germany studying Sanskrit and other languages, Ji returned with a Ph.D. to teach at China’s preeminent Peking University, where he soon became the chairman of its Eastern Languages Department. Though disliking the corrupt Chiang Kai-shek regime, he stayed away from politics, a field he’d never had any interest in. But when the Communists came into power in 1949, like most educated Chinese at the time, Ji saw hope for a stronger nation and more just society. [Source: Zha Jianying, New York Review of Books,January 26, 2016 *]

“Being a political drifter, however, was no longer an option. Under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), mass mobilization and political campaigns became a national way of life and no one was allowed to be a bystander, least of all the intellectuals, a favorite target in Mao’s periodic thought-reform campaigns. Feeling guilty about his previous passivity, Ji eagerly reformed himself. He joined the Party in the 1950s and actively participated in the ceaseless campaigns, which had a common trait: conformity and intolerance of dissent. In the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement, more than half a million intellectuals were denounced and persecuted, even though most of their criticisms were very mild and nearly all were Party loyalists. The fact that Ji was able to stay out of harm’s way was probably due to two factors: his poor peasant background and his reputation as one who never stuck his neck out and toed the Party line sincerely. *\

“In fact, he was doing just that in the first year of the Cultural Revolution. Peking University was quickly transformed into a chaotic zoo of factional battles, with frantic mobs rushing about attacking professors and school officials labeled as capitalist-roaders-in-power. A bewildered Ji tried his best to keep a low profile by hiding in the crowds. But he had a vulnerable spot: he abhorred a cadre named Nie Yuanzi, the leader of the dominant Red Guard faction on campus. Although every faction in China claimed loyalty to Chairman Mao, Nie enjoyed a special status: she penned the very first big-character poster of the Cultural Revolution, attacking certain Peking University officials and received Mao’s personal endorsement for it. Disgusted by her bullying style, Ji decided, in an uncharacteristically rash moment, to join her opponents’ faction. This was a fatal mistake. Nie’s followers took their vengeance immediately: they raided Ji’s home one night, smashing furniture and digging up, inevitably, some ridiculous evidence that Ji was a hidden counterrevolutionary. *\

“In fact, he was doing just that in the first year of the Cultural Revolution. Peking University was quickly transformed into a chaotic zoo of factional battles, with frantic mobs rushing about attacking professors and school officials labeled as capitalist-roaders-in-power. A bewildered Ji tried his best to keep a low profile by hiding in the crowds. But he had a vulnerable spot: he abhorred a cadre named Nie Yuanzi, the leader of the dominant Red Guard faction on campus. Although every faction in China claimed loyalty to Chairman Mao, Nie enjoyed a special status: she penned the very first big-character poster of the Cultural Revolution, attacking certain Peking University officials and received Mao’s personal endorsement for it. Disgusted by her bullying style, Ji decided, in an uncharacteristically rash moment, to join her opponents’ faction. This was a fatal mistake. Nie’s followers took their vengeance immediately: they raided Ji’s home one night, smashing furniture and digging up, inevitably, some ridiculous evidence that Ji was a hidden counterrevolutionary. *\

“From that moment onward, Ji’s life became a dizzying descent into hell. The ensuing chapters in the book are the most shocking and painful to read. There are many searing, unforgettable vignettes. Ji’s meticulous preparations for suicide, which was aborted only at the last moment by a knock on the door. The long, screaming rallies where Ji, already in his late fifties, and other victims were savagely beaten, spat on, and tortured. The betrayal by his former students and colleagues. An excruciating episode in the labor camp: Ji’s body collapsed under the strain of continuous struggle sessions; his testicles became so swollen he couldn’t stand up or close his legs. But the guard forced him to continue his labor, so he crawled around all day moving bricks. When he was finally allowed to visit a nearby military clinic, he had to crawl on a road for two hours to reach it, only to be refused treatment the moment the doctor learned he was a black guard. He crawled back to the labor camp. *\

Image Sources: Poster, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/. photos: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org, Ohio State University ; Wiki Commons, History in Pictures ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021