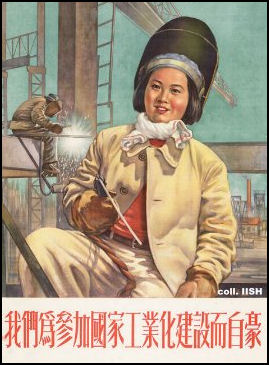

WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA

Mao-era poster In imperial times women were prohibited from holding official position and prevented by foot binding from doing many kinds of physical labor. They worked hard at domestic chores and produced textiles for the home and to sell. The Communists claimed to give equal rights in regards to work and employment opportunities. Equality existed more in theory than in practice. Women toiled in factories and on farms and worked as teachers and doctors but held relatively few positions with power or real decision-making.

There are a fairly large number of female doctors Even so women generally don’t hold very high-status positions or jobs. They are often encouraged to become secretaries, tour guides and hostess, not lawyers, managers and executives. Women are usually the last hired and the first laid off because unemployed women are considered less "socially destabilizing" than unemployed men.

Women traditionally control family finances. Millions of housewife have invested their family's money in real estate and stocks and four million operate private firms of a "substantial scale." A survey in 2000 by J. Walter Thompson on goals found 74 percent of the women interviewed ranked personal success first, 54 percent chose wealth and only 19 percent picked friendship.

In 2008, 67.5 percent of Chinese women over 15 were employed, according to Yang Juhua of Renmin University of China’s Center for Population and Development Studies, citing World Bank statistics. That was a drop from the most recent Chinese government data, from 2000, showing that 71.52 percent of women from 16 through 54 were employed, compared with 82.47 percent of men from 16 through 59. Ms. Yang has calculated that women earn 63.5 percent of men’s salaries, a drop from 64.8 in 2000. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times, November 25 2010]

There are more and more career women in China. Twenty percent of managers in China are women, compared to 40 percent in the United States and 8 percent in Japan. In one survey, 45 percent of Chinese women said they do no what to give up their careers to get married.

The Economist reported: “In Zhuhai a foreign manufacturer which hires staff from all over China says it prefers to recruit women. The managers believe that women are generally harder-working and tend to stay longer. But schools and universities have cottoned on to this now and set quotas on the number of women that firms can recruit. The company says that for every group of women it selects, it now has to hire a share of men too. [Source: The Economist , August 18, 2007]

Good Websites and Sources: China Labor Watch chinalaborwatch.org ; China Labor Bulletin clb.org.hk/en ; China Law Blog on New Labor Laws chinalawblog.com ; Book: Understanding Labor and Employment Law in China (Cambridge University Press, 2009) cambridge.org/us ; Gloomy Photos of Workers zhouhai.com ; Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China Book: “Factory Girls” by Leslie T. Chang (Random House, 2008) was described by the New York Times as “an engrossing account of the lives of young migrant workers in southern China.”

Articles About LABOR IN CHINA factsanddetails.com MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China ; LABOR-INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; WOMEN IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; PROBLEMS FACED BY WOMEN Factsanddetails.com/China

Women and the Choice Between the Private Sector and State Jobs

On her job at with a company that promoted Chinese brands, a 26-year-old Chinese graduate of a business school in France told the New York Times. “It was a really bad place.” Employees were fired immediately after promotional drives to slash costs. Working hours were long. A colleague who suffered a late miscarriage was ordered back to work within three days. Ms. Feng’s monthly salary was 5,000 renminbi, or about $745, without benefits.[Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times, November 25 2010]

In July, she quit — for the security of a “semi-state” organization run by the Ministry of Education. The pay is lower, about $625 a month, but lunch in the ministry canteen is free, and she gets benefits that hark back to socialist days, including a housing allowance. Hours are fixed, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., five days a week. Most important, her employer, the China Education Association for International Exchange, does not object to employees’ having babies and provides at least 90 days maternity leave at full pay.

The job may be “a bit boring,” but for now, she, like others, has made her choice. “The state sector is quite popular with women because their rights are better protected there,” said Feng Yuan, head of the Center for Women’s Studies at Shantou University.

Lack of Chinese Women in Management and Executive Positions

Didi Kirsten Tatlow and Michael Forsythe wrote in the New York Times, “Chinese women are losing ground in the work force compared with men, their representation falling steadily with each rung up the professional ladder. Women make up 44.7 percent of the work force, but just 25.1 percent of people with positions of “responsibility,” according to China’s 2010 census. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow and Michael Forsythe, New York Times, February 20, 2015 /^]

“At the very top, their share falls still further. According to corporate records examined by The New York Times, fewer than 1 in 10 board members of China’s top 300 companies are women. That measure, significantly smaller than the proportion of women on corporate boards in the United States and much of Europe, is based on a review of the boards of directors of every company in the CSI 300 index, China’s equivalent to the S.&P. 500, which includes a wide swath of the economy from mining to pharmaceuticals. Among the CSI 300 companies, 126 have no women on their boards, according to their 2013 annual reports, the latest available. “We call it the ‘sticky floor,’” Ms. Feng said. “There is a glass ceiling here too, but most women never even get off the sticky floor.” /^\

“By comparison, women hold 19.2 percent of the directorships on S.&P. 500 companies, according to Catalyst, a nonprofit group that seeks to promote women in business. In Europe, about 18 percent of board members in the Continent’s 610 biggest companies are women, according to the European Commission. /^\

“While the advantages of having women in the boardroom are broadly accepted in global business circles, in China the idea meets with incomprehension, even boredom, among business leaders. Women as directors was “a noble question,” said Jiang Zhinan, a spokesman for the state-owned Aluminum Corporation of China, but one that his company had not considered. The company has no women on its eight-member board. Dongfang Electric, one of the world’s biggest makers of electric power turbines, also has no women on its nine-member board. “We’ve never thought about it,” said Zhang Linchao, the director of the company’s general offices. Asked if the company would answer questions on the subject, he declined. “It’s irrelevant,” he said. The pattern is especially pronounced at state-owned companies, where the government could simply order higher female participation if it wanted. Of the 31 companies on the CSI 300 that have no women as senior executives, 30 are majority state-owned. /^\

Lonely Life of Few Chinese Women in Management and Executive Positions

Didi Kirsten Tatlow and Michael Forsythe wrote in the New York Times, “One Chinese company that does have women on its board, Haier, a manufacturer of home appliances, says the diversity makes business sense. “Females act quite differently, bringing diversity and ideological pluralism,” Ming Guozhen, a deputy general manager, wrote in a faxed reply to questions. “To some degree, this contributes to more reasonable decisions and reducing risk.” Haier’s two women directors may also be more attuned to the company’s customers. “Women are the biggest consumers and are in charge of finance in the home, so they can express consumers’ opinions better,” Ms. Ming said. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow and Michael Forsythe, New York Times, February 20, 2015 /^]

“Some companies not listed on the CSI 300, including the Internet giants Baidu and Alibaba, also have more women in top positions. Those women often find themselves on a lonely frontier. Fu Xin, 32, an architect who designs car dealerships for a German company, says she rarely meets women at her level. “It’s all men,” she said. “When clients come up to me at the airport or the dealership they often look past me for the boss.”/^\

“But the attitudes of the successful women she has encountered are not always much different from those of their male counterparts. On a recent trip to Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong Province, a rare female client, the head of a new dealership, took her under her wing. “She said, ‘You should do the most important thing in your life now,’ ” Ms. Fu said. “Find a husband.” /^\

“Nor do the few women in the top echelons of business do much to promote their cohorts, several businesswomen said. Dong Mingzhu, president of Gree Electric, an air conditioner manufacturer with sales of $22.5 billion last year, blames women for their poor showing in the workplace. “Women don’t try hard enough,” she said in an interview at the company’s headquarters in Zhuhai, in southern China. “They are too happy to go off and find a man to rely on.” /^\

Working Urban Women in China

There are success stories of women who left their villages as teenagers to take $50 a month jobs at hotel and factories in Shenzhen, saved enough to go to Beijing and get better jobs there selling real estate for $500 a month and in their free time studied English and earned company management degree to get even better jobs.

In a return to the class system that the Communists tried to eliminate, many young women from the countryside are coming to Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou and other cities to work as maids and servants for rich people. They typically get paid $50a month and put in 10 hour days. The government tolerates the practice, more concerned about employing people than living up to Communist ideology.

The treatment of the maids depends on their employers. Some give them heavy workloads, and are given a hard time about the way they do their chores. Many maids complain about sexual advances and getting little to eat other than the family leftovers.

Working Women in Modern, Changing China

“Three decades after China embarked on dazzling economic reforms, much has changed for women,” Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote in the New York Times. “Unlike their mothers, whose working — and, often, private — lives were determined by the state, women today can largely choose their paths. Rural women are no longer tethered to communes; urban women no longer are assigned jobs for life or need permission from work units to marry, although all women must apply for permission to have a child. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times, November 25 2010]

“Yet along with freedom has come risk, as socialist-era structures are dismantled and powerful cultural traditions that value men over women, long held in abeyance by official Communist support for women’s rights, return in force. Many employers are choosing not to hire women in an economy where there is an oversupply of labor and women are perceived as bringing additional expense in the form of maternity leave and childbirth costs. The law stipulates that employers must help cover those costs, and feminists are seeking a system of state-supported childbirth insurance to lessen discrimination.”

Guo Jianmei, director of the Beijing Zhongze Women’s Legal Counseling and Service Center, insists that, over all, women today are in a better position than they were three decades ago. “They know so much more about their rights,” she told the New York Times. “They are better educated. For those with a competitive spirit, there’s a world of opportunity here now, whether they are businesswomen, scientists, farmers or even political leaders. There really have been huge changes.”

Women’s rights are well protected, at least on paper. In 2005, the government amended the landmark 1992 Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests, known as the Women’s Constitution, to make gender equality an explicit state policy. It also outlawed, for the first time, sexual harassment.

Working Women in China Seek Relief from Dreary Jobs by Online Dating

Sim Chi Yin wrote in The Straits Times, “Advertising executive Wang Xin, 29, on the other hand, is equally jaded about her job but puts her energy into finding a husband - by dating assembly-line style. She spends hours every night 'mechanically' checking two match-making websites "like a stockbroker checking stock prices", she said. She exchanges e-mail or messages on social networking sites with the men she might have some luck with. Wang has dated - and broken up with - three men in the past eight months. [Source: Sim Chi Yin, The Straits Times, September 13, 2010]

"I feel very trapped in my boring job of six years, but I keep thinking I have to first find someone to marry and then move on in my career, so I keep trying," she said. She does not quite see herself as a 'plasticine' person, however. "I feel stuck in life. And I feel confused, trapped. But I can't find the motivation to do something about it," she said. "I want to change my life, but I don't know the way out."

Wage-Earning Rural Woman in China

The economic reforms have helped to raise the status of women as "excess women" have left their villages to work in factories and send their earnings home. One analyst at the Ford Foundation called the migrant worker phenomena as "the single most important element transforming Chinese society."

About half of the estimated 85 million people who have left their home province in search of work are women. It is not unusual for girls to be pulled out of school when they are ten or so to work in the fields. When they are 14 or 15 they are shipped off to work in factories far from their home towns. They typically earn more and save more than migrant men who can often only get jobs as manual laborers and don't get their room and board paid for like factory women do. Debunking the traditional preference for boys, one village woman with a daughter working in a factory told the Los Angeles Times, "I think girls are better than boys."

Many young women give all their money to their parents in their home village. The Los Angeles Times talked to one woman who worked at a Shanghai cigarette lighter factory and sent her salary of $70 a month to her family in a village 1,500 miles away. The family earned only $15 from its harvest and used the money their daughter sent to but buy seed and fertilizer and make their farm more profitable.

The money is also used to buy livestock, home additions, a plow or tractor, a color television. Some try to save enough money to open a small grocery store or clothes shop back home. Those that have a spouse and children behind see them maybe once a year.

As a result of the "excess women" phenomena, families are spending more money on their daughters, giving them more attention and making more an effort to ensure they get an education. Young women are saying they enjoy life more and the suicide rate among young has dropped.

Women Factory Workers in China

Electronics worker

Many of the employees that work in the toy, textile and shoe factories that produce goods for Mattel, Nike, Reebok and Levis are young peasant girls in their late teens and early 20s. Many workers live in "three-in-one" facilities with production, warehouses and living quarters. These facilities are illegal, in part because flammable material are often stored near where people sleep.

In most cases the girls work six days a week from around 7:30am to 6:00pm, with an hour off for lunch and maybe 30 minutes break for dinner Overtime begin at 6:00om and runs past midnight during the busy season. One their days off workers often wander around in their uniforms with their ID badges. Some work seven days a week so they can take a week or two off to go to their hometowns during the Chinese New Year.

Depending on the experience and overtime young women factory workers get paid between $70 and $250 a month. From this fees are deducted for housing and meals. Sometimes workers are fined for things like spending more than the allotted five minutes in the toilet. Workers often work even when they are sick and have managers standing over their shoulders, telling them to work fast. To keep workers from quitting factories often delay paying salaries so workers worry they will lose several months pay if they quit.

A worker promised a $120 a month salary, regarded as good pay, may be forced to sign a contract with a basic salary of $24 minus $13 for room and board. To reach a $120 they must fulfill quotas that are almost impossible to fulfill even with incredibly long hours. Many contracts demand that workers pay $58 to their bosses if they didn’t complete their contract. If they “steal intellectual property” by taking a job with a competitor they have to pay $2,400. Kathie Lee Gifford handbags, sold at Wal Mart, were made at a Chinese factory that beat workers and deducted up to 70 percent of their pay for food and lodging. [Source: New York Times]

Many migrant speak mutually unintelligible dialects. Large factories often have separate cafeterias that serve dishes native to different regions.

Factory bosses like young female workers because they are regarded as more hard working and manageable. Some girls remain for years in their dead end jobs; others advance in the company or leave and start their own businesses. Some want to marry their hometown sweethearts. Others date only city guys.

The work is hard but the experience in an adventure and an opportunity that offers infinitely more possibilities than village life back home. As bad as thing are, these women are often looked upon with envy when they return to their villages and view themselves as more worldly and sophisticated than other villagers.

Female Workers at a Chinese Barbie Factory

Worker at a Disney factory

In toy factories, young female workers often work assembly line style, performing the same task again and again, with runners bringing them parts and taking away the products. A typical worker at the Barbie factory in Guangdong province near Hong Kong is an unmarried woman between 18 and 23 from Sichuan province who works at the factory for between two to five years or until she earns enough money to return home with a dowry. Many of the girls are younger children of families that already have a son. [Source: Anita Chen, Wall Street Journal, October 29, 1996]

The young women are housed in drab dormitories that hold thousands of migrant laborers. Twelve girls are crammed into a narrow room with a concrete floor, a single fluorescent bulb and a tiny bathroom. Kathy Chen wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "Cold water sputters on for a few hours twice a day, while the meat served is too tough to swallow and has hair in it." Many of the girl's don't mind the housing, because it is better than what they are used of back home.

Meals are subsidized and medical care is provided In other factories there is only one bathroom for more than a hundred workers and fights sometime break out in the long lines to get in. Some workers get meat or fish or only twice a month. In their free time many of the girls dress in pretty clothes and stay in their rooms. One girl told Mike Edwards of National Geographic, "It's very hard of have contact with town people. We don't speak Cantonese. The town and the workers are different communities."

Chen took bus journey with a young girl who left her village in the Sichuan province for a job at a Barbie factory in Guangdong. The young girl suffered from homesickness, sleepless night, cold and nausea during the four-day trip on the crowded, smelly bus. The only food that the girl could keep down were some sugar cane, oranges, peanuts and salted duck eggs her mother packed for her. After arriving she attend a battery of lectures and medical check-ups. Among other things shw as told that if she misses one day of work money will be taken from her salary and if she misses three days in a row, she’s fired. After her ID and papers were checked to make sure she wasn’t married she signed a contract. Girls that were promised 350 yuan a month end up with a starting salary of 200 yuan ($24) a month.

The popular Bratz dolls are made in factory in Shenzhen in southern China where workers are forced to toil up to 94 hours a week. Workers are paid the equivalent of 17 cents for each doll, which retails for at least $16 a piece in the United States.

Female Workers at Sport Shoe Factories in China

Factory Girls, the book

Conditions are similar in the Taiwan-run You Yuan shoe factory in Dongguan (near Hong Kong) that makes 12 brands of shoes including Nike and Reebok. The factory employs 40,000 workers, 70 percent of the female, in the 1990s. [Source: Anita Chan, Washington Post, November 3, 1996]

"You Yan is run in a decidedly military style," wrote Anita Chan in Washington Post. "New recruits are given three days of 'training.' The first day, according to one of them, is largely spent marching around the compound, barked at by a drill sergeants. At 6:30 pm commands could clearly be heard in the background: 'Left! Right! Left! Right! About Turn! March!'" Later they have run 1.5 kilometers mile and do as many push-ups as they can within a minute.

Manufacturing shoes is generally a three step process: 1) first one group cuts the pieces rubber foam and fabric; 2) another group sews and glues the pieces together; and 3) a third group glues the sole to the shoe.

Most of the work at You Yuan entails sewing pieces of shoe together with industrial sewing machines. Many workers put in 12 hour days and get one day off every two weeks. During busy period, worker have to work from dawn until 11:00 p.m. For this the workers get paid about 25 cents an hour. The turnover rate at the factory is 7 percent a month. Girls who quit before their contract is through loose two weeks pay.

The companies provide meals and living quarters. At meal time, the girls only have 10 to 15 minutes to eat and they can only start eating when a bell rings. Girls on their way to the cafeteria file up one set of stair while girl on their way you go down another. Workers who are late are penalized a half day's pay. In the evening, sometimes the girls gather for rallies in a factory courtyard shouting, "Be respectful toward my work! Be loyal! Be creative! Be of Service!"

See Factory Diseases

Image Sources: 1)Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; 2, 4) Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china ; 3, 5) China Labor Watch ; Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015