CLOTHES IN CHINA

Mandarin collars in the 1920a China gave the world mandarin collars, frogged fastenings and butterfly buttons. The Chinese have traditionally worn layers of thick cotton coats in the winter. Even today cold days and very cold days are often referred to as "two-coat weather" and "three-coat weather." In the Mao era, many people wear puffy-looking denim jackets and trousers in the winter that were lined with cotton and look as if they were stitched from quilts. Even today old people used to harsh winters wear three sweaters, quilted pants and slippers in their homes.

Many minority groups maintain their traditional clothing. Tibetans dress in layers of clothes to protect themselves from the harsh weather. Uighur women wear long skirts and bright-colored scarves; the men wear embroidered caps. Peasant girls often wear loose shifts or balloon-seated pants. Small children sometimes wear pants with the seat cut out so they don’t soil their clothes. Simple lightweight shoes are the norm. Many peasants wear plastic sandals. Some still wear straw shoes. In western China, Muslim women wear veils, often not for religious reasons, but to keep out the dust.

According to Bloomberg in 2020 China makes more than 5 billion T-shirts a year. In the old days carpenters wore padded jackets for protection from the cold but no shoes. According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: During the Mao era “ city streets were uniformly grey and dark; men and women, young and old, wore clothes of the same style and the same color. Today, in the frozen north, down jackets, woolens, and fur overcoats in red, yellow, orange, and other bright colors liven the bleak winter scene. In the south, where the climate is milder, people choose Western suits, jeans, jackets, sweaters, and other fashionable clothing to wear year-round. Famous brand names and fashions are a common sight in large cities, and they sell quite well. Cheaper and more practical clothing is also available. Similar changes also have occurred in rural areas, especially among the new class of well-to-do farmers. However, in less advanced rural areas, Han peasants still wear their "Mao suits" (the plain, two-pieced utilitarian attire named after the former Chinese leader). [Source: Bloomberg, C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, ” Cengage Learning, 2009]

According to Bloomberg: An aspirational middle class, combined with a boom in e-commerce, has turned China into the world’s biggest fashion market, overtaking the U.S. in 2019. Greater China accounts for a fifth of Japanese retail giant Uniqlo’s global revenue and the company’s sales in the region rose almost 27 percent in the 2017-2018 fiscal year to more than $4 billion. Most of China’s purchases are fast fashion — mass produced, cheap, short-lived garments. [Source: Bloomberg News, October 19, 2020]

See Separate Articles: BEAUTY IN CHINA: FACE SHAPE, WHITE SKIN AND PAGEANTS factsanddetails.com ; HAIR AND HAIRSTYLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CLOTHES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FASHION IN CHINA: WESTERN BRANDS, FOREIGN DESIGNERS AND HAN CLOTHING factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FASHION DESIGNERS factsanddetails.com ; COSMETICS, TATTOOS AND JEWELRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COSMETIC SURGERY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ASIAN PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; University of Washington washington.edu/china; Chinatown ConnectionChinatown Connection ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Clothing” by Hua Mei Amazon.com; “Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day” by Valery Garrett Amazon.com; “In the Mood for Cheongsam: A Social History, 1920s-Present” by Lee Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen Amazon.com; “How to Make a Mao Suit” by Antonia Finnane Amazon.com; “5000 Years of Chinese Costumes” by X. Zhou Amazon.com; “Ruling from the Dragon Throne: Costume of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)” by John E. Vollmer Amazon.com; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “Chinese Fashion: From Mao to Now” by Juanjuan Wu and Joanne B. Eicher Amazon.com; “Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation: by Antonia Finnane Amazon.com;

Silk in China

Used for thousands of years to make clothes in China, silk is a wonderfully strong, light, soft, and sensuous fabric produced from cocoons of the Bombyx caterpillar, or silkworm. Of all the fabrics, silk is regarded as the finest and most beautiful. It has a wonderful sheen — the result of triangle-shaped fibers that reflect light like prisms and layers of protein that build up to a pearly sheen — and can be dyed a host of wonderful colors. The former fashion editor of the Washington Post Nina Hyde wrote, “Designers revel in its feel, its look, even its smell." [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

Used for thousands of years to make clothes in China, silk is a wonderfully strong, light, soft, and sensuous fabric produced from cocoons of the Bombyx caterpillar, or silkworm. Of all the fabrics, silk is regarded as the finest and most beautiful. It has a wonderful sheen — the result of triangle-shaped fibers that reflect light like prisms and layers of protein that build up to a pearly sheen — and can be dyed a host of wonderful colors. The former fashion editor of the Washington Post Nina Hyde wrote, “Designers revel in its feel, its look, even its smell." [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

Silk can be used for all sorts of things. In addition to being woven into fabric, it has been made into cold cream in China, beauty powder and parachutes in the United States, teeth braces in Italy and fishing nets around the world. Bicycle racers say that tires made with silk give them a smoother ride and better traction. Skiers like it because it wicks away moisture. Scientist say it is stronger than steel. In Japan silk artists are revered as national treasures. In India corpses are covered with silk shrouds as a sign of respect. Frugal Ben Franklin splurged on a silk kite for his famous electricity experiments and the first French atomic bomb was dropped from balloon partly made of silk.

Silk production is largely automated and done in factories but the raising of silk worms to make silk is still very much a “cottage industry” done primarily at people’s homes. In some places governments provide anyone who is willing to raise silkworms with 20 kilograms of very small silkworm grubs, which are placed in special boxes in special rooms and fed mulberry leaves gathered from trees near the homes of the people raising them.

Silk brocade is used to make special clothes worn by men and women on New Years's, weddings and celebrations for the birth of a son.

See Separate Article SILK IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SILK, SILK WORMS, THEIR HISTORY AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Cashmere in China

China is the world’s leading producer of de-haired cashmere and cashmere finished products, accounting for about 70 percent of the world's output. The raw material resources and processing capacity in China dwarfs that of any other country. The industry emerged out nowhere in the 1990s and really taken off since joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. [Source:Cashmere World 2013 *]

In the early 2000s, China was home to more than 60 million cashmere-producing goats. They produced 20,000 tons of cashmere annually. The result of all these goats was an oversupply of cashmere often of dubious quality. Most cashmere goats in China are raised in Inner Mongolia or Xinjiang.

Marina Romanov wrote in Mongolia Briefing: “Cashmere down hair in China comes from goats grazing on the plains of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and the Himalayan Mountain highlands leading to the Tibetan Plateau — regions surrounding the Gobi Desert, which also constitutes a third of Mongolia’s territory. The fibers are locally combed, cleaned, dyed, and spun before being knitted into fabric in northern Chinese mills or exported. [Source: Marina Romanov, Mongolia Briefing, February 24, 2012]

According to Cashmere World: In the past 30 years the development of China’s cashmere industry was reflected in the quantity of cashmere produced. As the industry matured it became evident that growth will be limited by the amount of material available. The future of the cashmere industry in China will be about higher value-added products and established brands. Price competition will abate and be replaced by quality and brand competition. This implies that Cashmere companies worldwide will have to rely on innovation to achieve sustainability, launch brands and implement vital marketing strategies to remain competitive. *\

See Separate Article CASHMERE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com l CASHMERE factsanddetails.com

Clothing in the Mao Era

Until the 1970s, most Chinese wore drab, sexless, blue, grey or black Mao suits or Army-surplus clothes. Now they mostly wear Western clothes. Now many dress in loafers and jeans. Before the reform period, clothing purchases were restricted by rationing. Cotton cloth consumption was limited to between four and six meters a year per person in the 1970s.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “After the Communist Revolution, the Mao suit became a symbol of proletarian unity, and was regularly worn by party cadres. The collars, pockets, and seams of the Mao suits often appeared to be the same, but they were not necessarily identical. Later, political leaders were not the only ones to wear Mao suits. People of both genders, in all areas, and in all different kinds of professions began wearing variations of the Mao suit on a daily basis. Children's clothing, while not generally called Mao suits, could also indicate political allegiance. The red scarves seen around the necks of the children in these two pictures indicate that they are young pioneers. The scarves became important symbolic objects to many of the children in this period. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

Mao Suit

Mao in Mao suit

In the Mao era, the Chinese wore cheap blue cotton outfits which Westerners call ‘Mao Suits’. The Chinese call them the ‘Zhong-shan-fu’ or ‘Sun Yat-sen suits’, since Sun, the father of Modern China, first advocated wearing simple traditional peasant designs as a classless national uniform. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: ““Despite its modern-day name, the roots of the Mao suit can be traced back to Sun Yat-sen and the Nationalist government. In an attempt to find a style of clothing that suited modern sensibilities without completely adopting western styles, Sun Yat-sen developed a suit that combined aspects of military uniforms, student uniforms, and western-style suits. In the late 1920s civil servants of the Nationalist government were required by regulation to wear the Sun Yat-sen suit which would later be called the Mao suit. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

The "Zhongshan suit" is named after the great revolutionary pioneer Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yat-sen) . In the last years of the Qing Dynasty, Westerners ridiculed the Chinese as "the sick man of East Asia" and a "pigtail army" in "mandarin jackets and gowns." Sun hated both Western imperialism and the corruption of the Qing Dynasty. He organized a group of ardent patriots to set up the Revive China Society aiming at "expelling the invaders and recovering China." Through the sacrifice of a lot of lives, the 1911 Revolution overthrew the Chinese monarchy and set up the Republic of China. After that, Sun issued a series of policies, decrees and reforms that included "cutting the pigtail" and "changing the clothes". He proposed to "wash away old habits and customs and be new Chinese people." After widely soliciting suggestions and conducing discussions, Sun Zhongshan concluded that "the formal dress must be changed, and the informal dress is at the people's willingness." He helped design a new style of clothes for himself and the Chinese people— a simple set of clothes with the Han people characteristics, called "Zhongshan dress." [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~]

According to the Chinese government: “The Zhongshan suit has absorbed the strong points of the western suit. It has a straight collar and four pockets with buttoned covers. The two pockets below are big enough to hold books. The trousers are designed like this: the front seam is sewed with hidden buttons; on either side there is a hidden pocket. The trousers waist is wrinkled.” Sun took the lead and wore the suit at various kinds of occasions. “Its appearance is symmetrical, beautiful, practical, convenient and in good taste. It can be made of both the high-class dress material and the common cloth. Advocated by Sun the Zhongshan dress became a fashion in the country at that time. The Mao suit was modeled on it. Today, it is still one of the most basic styles of clothing among the Han people.

The Mao suit as the standard form of Communist dress, Dr. Li Zhisui, Mao's doctor, said, evolved out of the chairman's distaste for protocol. In 1949 his chief of protocol told him that it was good idea to wear a dark-colored suit and black leather shoes while receiving foreign ambassadors. "Mao refused and began wearing what we then called the Sun Yat-sen suit and black leather shoes," Li wrote. "When other leaders imitated him, the name of the outfit changed. The grey “Mao suit” became the uniform of the day. The protocol chief was fired and later committed suicide during the Cultural Revolution." [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

Clothing in the Post-Mao Era

Before the reform period, clothing purchases were restricted by rationing. Cotton cloth consumption was limited to between four and six meters a year per person in the 1970s. In the 1980s one of the most visible signs of the economic "revolution" was the appearance in Chinese cities of large quantities of relatively modern, varied, colorful, Western-style clothes, a sharp contrast to the monotone image of blue and gray suits that typified Chinese dress in earlier years. Cloth consumption increased from eight meters per person in 1978 to almost twelve meters in 1985, and rationing was ended in the early 1980s. [Library of Congress]

“Production of synthetic fibers more than tripled during this period; in 1985 synthetics constituted 40 percent of the cloth purchased. Consumers also tripled their purchases of woolen fabrics in these years and bought growing numbers of garments made of silk, leather, or down. In 1987 Chinese department stores and street markets carried clothing in a large variety of styles, colors, quality, and prices. Many people displayed their new affluence with relatively expensive and stylish clothes, while those with more modest tastes or meager incomes still could adequately outfit themselves at very low cost.

“Production of synthetic fibers more than tripled during this period; in 1985 synthetics constituted 40 percent of the cloth purchased. Consumers also tripled their purchases of woolen fabrics in these years and bought growing numbers of garments made of silk, leather, or down. In 1987 Chinese department stores and street markets carried clothing in a large variety of styles, colors, quality, and prices. Many people displayed their new affluence with relatively expensive and stylish clothes, while those with more modest tastes or meager incomes still could adequately outfit themselves at very low cost.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “After the Communist Revolution, western-style suits fell out of favor in China because of their association with western imperialism. Thus, in October 21, 1984, when Hu Yaobang, the General Secretary of the Communist Party, appeared on television at a meeting of the Central Committee wearing a dark-blue western style suit, he was making a bold sartorial statement. To many Chinese watching the televised meeting, his appearance was extraordinary. Prior to this event, Communist Party leaders had always appeared at formal functions inside the PRC in Mao suits. Hu's move was possible because of the more relaxed atmosphere following the ascendancy to power of Deng Xiaoping in 1978 and his introduction of political and economic reforms. From this point on, as China entered into the international political stage and global economy, government and business leaders had a wider range of choices of how to present themselves. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Before 1984 communist officials would occasionally don a western-style suit when traveling outside China. By the end of the twentieth century the western-style suit had been fully adopted by Chinese men as the preferred choice of clothing for all formal, official, and business affairs. By the 1990s, dress in China had become extremely diverse, with fashion-consciousness especially pronounced in the large cities.

Men’s Clothes in China

Chinese men are not known for being well-dressed or suave. Many wear white socks with dark shoes. Some pull their pants up near their chests. In the winter long underwear is often seen poking out from under sleeves and trouser hems. It is summer it not unusual to see men sitting around without their shirts or walking around on trains and on the streets in their pajamas.

Describing one guy he knew, Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “Yuan wore a white tank top, khaki shorts, leather loafers, and black socks pulled up to his kneecaps. He carried a money bag in one hand and a dirty white towel in the other. He puffed in the heat; he used the towel to mop sweat off his neck.”

These days top officials and businessmen favor Western-style suits and ties. Mao suits are largely a thing of the past.

Green hats have traditionally been worn by men who wives have cheated on them.

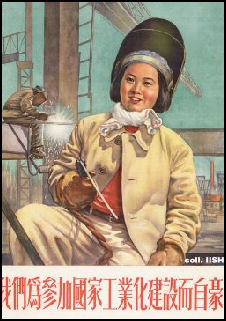

Feminine Clothing in Mao Era

In the Mao era, clothes were made with little regard to sizing and fit. Stores had no place to try on clothes and costumers couldn’t bring back clothes that didn’t fit. In some stores saleswomen grabbed women by their breasts to determine their size.

The idea of wearing colorful clothing during the Mao years was considered scandalous and bourgeoisie. During the Cultural Revolution one man told writer Paul Theroux, the Red Guard "used cut your cuffs if they were too wide or too narrow. They cut your hair if it was too long."

During the Cultural Revolution some women used to wear frilly lace blouses and brightly colored sweaters under their baggy Mao suits and compare them in the washroom before starting work. In 1976 Chinese journalists were shocked when they found a young female shipyard worker "wearing a pink blouse under her Mao jacket." British journalist Martin Wollacott wrote: "that scrap of cloth sticking out from under her collar, a tiny signal of forbidden femininity, was the basis for many essays on how the wind was shifting in China."

Fur Coats in China

In a country wear people eat dogs and take tiger bone medicines, wearing a fur coat is not looked upon with kind of disgust that it in the West. Harbin-based Northeast Tiger Fur is one of the world’s largest fur companies.

Chaowal Street is a dusty market alley in Beijing, featuring more than 100 stalls selling nothing but fur garments: coats, jackets, hats, gloves and other items made from mink, rabbit, goat, fox and even dog. The most serious buyers are Russians. Almost one out of three coats ends up in former Soviet Union.

One Lithuanian buyer on Chaowal Street told the Washington Post he visited Beijing every three weeks and said he purchased thousands of coats. A Russian trader said, "The quality is not very good. But its cheap, and it stand up better than our fabrics.”

When told about animal rights campaigns against fur coat sellers in the West, one Chinese trader on Chaowal Street told the Washington Post, "We've heard that. But these animals are raised for their fur. Americans eat beef don't they? You kill those big animals for food: we kill those little minks for fur. What's the difference?"

Pulled Up Shirts and Exposed Bellies in China

On hot summer days in Beijing and other places, it is a common sight to see men running around without shirts or with their shirts rolled up under their armpits exposing their bellies. They hang around, play cards, drink tea, stroll on the sidewalks without their shirts, exposing their less than ideal bodies. Flabby tummies and spares tires are the norm, not rippling abs. They also like to pull up their trousers past their belly button, with the legs rolled up. One Chinese academic told the Los Angeles Times, “Foreigners who visit always ask why are there so many half-naked men in Beijing."

Chinese men expose their bellies to the air as a means of cooling themselves. Some also hike up their pant’s legs. Even though men from a wide range of ages engage in the custom those that do it are smirkingly known as “bang ye” (“exposing grandfathers”). One man spotted with his flabby tummy exposed told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t know, it just feels cooler. Look, you just shake your shirt to create breeze.” [Source:John Glionna, Los Angeles Times, August 2010]

Many younger, more sophisticated Chinese don’t like th custom. A man who works at department store in told the Los Angeles Times, “It lower’s Beijing’s standing as an international city. If my dad reaches for his shirt when I’m out with him, I threaten to go home. It’s just so embarrassing.”

The habit is actually a sort of compromise to the custom of men going totally shirtless. A Chinese medicine doctor told the Los Angeles Times, “People chose to expose their belly because they feel so hot in summer but feel embarrassed to take off their shirts completely.”

Authorities began to crack down on the no-shirt habit during the pre-Olympic run up. During that campaign the Beijing Truth Daily ran pictures of men who went around shirtless, often with less than attractive upper bodies, in an effort to shame them into dressing respectfully.

Slit-Seat Pants for Toddlers

“Kaidangku” are pants for toddlers with a slit in the seat that allow a child to relieve himself without removing his paints. Sometimes foreigners are shocked to seem them but many Chinese defend them as comfortable and healthy, plus they make potty training easier. Sex shops sell adult verison of kaidangku that are “transparent, green and charming” and “convenient for you and your partner.”

Pajama-Wearing in Shanghai

Mother and peeing child

Especially in Shanghai it is not uncommon to see men in pajamas and women in nightgowns at busy markets or walking around in the street or in hotel lobbies. Some people slip into their pajamas when they come home from work and go shopping. Others get comfortable on long distance train rides by wearing pajamas.

In Shanghai, wearing pajamas in public began in the early 1990s, when people traded in their Mao suits for more comfortable and fashionable clothes. One Shanghai resident told AP, Only people in the cities can afford clothes like this. In farming villages, they still have to wear old work clothes to bed.A 17-year-old high school who likes to wear a pink nightgown with a kitten face said, “Pajamas look and feel good. Everyone wears them outside. No one would laugh.

Gao Yubing wrote in the New York Times, “Pajamas — not the sexy sleepwear you find at Victoria’s Secret, but loose-fitting, non-revealing PJs made of cotton or polyester — have been popular in Shanghai since the late 1970s, when Deng Xiaoping, then China’s leader, sought to modernize the economy and society by opening up to the outside world. The Chinese adopted Western pajamas without fully understanding their context. Most of us had never had any dedicated sleepwear other than old T-shirts and pants. And we thought pajamas were a symbol of wealth and coolness.” [Source: Gao Yubing, New York Times, May 17, 2010]

Shanghainese began wearing them to bed — but kept them on to walk around the neighborhood, mainly out of convenience. At that time in Shanghai, people lived in crammed, communal-style quarters in shikumen — low-rise townhouses in which families shared toilets and kitchens. Through the 1980s and “90s, the average person had less than 10 square meters of living area. To change out of one’s pajamas just to walk across the road to the market would be too troublesome and unnecessary.”

Besides, as a retiree told a news reporter: Pajamas are also a type of clothes. It’s comfortable, and it’s no big deal since everyone wears them outside. and Mrs. Wang, who lived on the street where I grew up in Shanghai, used to stroll after dinner in their pajamas — nice matching costumes for a loving couple, now that I think about it. Then Wang would go out to buy cigarettes. In the mornings, Mrs. Wang, still in her pajamas, would dash to a street stall to pick up sheng jian (fried buns) for breakfast...My own family, a little particular about clothing and slow with fashion, happened not to be part of the pajama troupe.”

Anti-Pajama-Wearing Campaign in Shanghai

For Shanghai’s many pajama wearers, the start of Expo 2010 also signified the start of a nightmare,” Gao Yubing wrote in the New York Times. “Catchy red signs reading Pajamas don’t go out of the door; be a civilized resident for the Expo are posted throughout the city. Volunteer pajama policemen patrol the neighborhoods, telling pajama wearers to go home and change. Celebrities and socialites appear on TV to promote the idea that sleepwear in public is backward and uncivilized.

But even those of us who never wore PJs in public are unhappy about the ban. Two journalists from Hong Kong’s Weekend Weekly magazine have already challenged it. They marched in their silk pajamas along Nanjing Road, a major shopping area in central Shanghai, and sat down in a restaurant. They met only one pajama-wearing comrade, and many people made fun of them (maybe because on a rainy day they were wearing silk jammies rather than the quilted or heavy flannel styles normally worn in cool weather). It wasn’t what they expected in Shanghai.

Yang Xiong, the executive vice mayor of Shanghai and a director of the executive committee for the Expo, has acknowledged the practical limitations that led to pajama wearing, but still insists it is now inappropriate. The Expo, the logic goes, offers a perfect opportunity to kick the habit; with a large influx of foreigners in town (though, in fact, they are expected to account for only 5 percent of all visitors to the Expo), we don’t want to ruin our cosmopolitan image.

Yet even foreigners are disappointed about the pajama ban. Justin Guariglia, an American photojournalist who showcased Shanghai’s lively pajama scene in his 2008 book, Planet Shanghai, says the fashion adds to the city’s character. A British friend of mine told me last winter, before traveling to Shanghai for the first time, I want to see the Bund, the Jin Mao Tower and Shanghainese women in pajamas!

The historic buildings along the Shanghai Bund will be there for a long time to come. So will the 88-story Jin Mao Tower. But street pajamas may disappear as everyone moves into modern, spacious apartments. By then, some Chinese fashion designer might, as Dolce & Gabbana did last year, send models down the runway wearing pajamas — and how the audience will applaud!

Image Sources: University of Washington except men's clothing, Columbia University; Imperial clothing, Toranhouse, Mao-era posters, Landberger, and Western fashions, Perrechon.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021