TRADITIONAL CLOTHES OF CHINA

On the clothes and hairstyle of a kneeling archer in the China's Terracotta Army,Verity Wilson, expert on the history of Chinese textiles and clothing, told the BBC: “If we look back at pottery figures, at stone relief carvings, we see that in fact trousers were fashionable, or at least practical, for men in Liu Bei's time. Liu Bei would have worn trousers, a sort of skirt-like scarf around his waist, a sleeveless jacket and armour over his chest, of course. Like all Chinese men at the time, he would wear his hair long, curled up in a bun at the top, and fastened with wonderful trailing silk scarves and sometimes just bound with a jade band. He was rather an impressive figure, and I think that some of the depictions of him today probably are not far off what he really looked like. [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 15, 2012]

On the clothes and hairstyle of a kneeling archer in the China's Terracotta Army,Verity Wilson, expert on the history of Chinese textiles and clothing, told the BBC: “If we look back at pottery figures, at stone relief carvings, we see that in fact trousers were fashionable, or at least practical, for men in Liu Bei's time. Liu Bei would have worn trousers, a sort of skirt-like scarf around his waist, a sleeveless jacket and armour over his chest, of course. Like all Chinese men at the time, he would wear his hair long, curled up in a bun at the top, and fastened with wonderful trailing silk scarves and sometimes just bound with a jade band. He was rather an impressive figure, and I think that some of the depictions of him today probably are not far off what he really looked like. [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 15, 2012]

The Mongols “introduced buttons," Wilson said. "Prior to this time, men and women had always closed their robes with some sort of belt. But, the Yuan dynasty is credited with bringing to China the toggle-and-loop button, which now today we just call Chinese. It's a real marker of Chinese dress that they're closed with these toggle-and-loop buttons. But they didn't really come in until the Yuan dynasty."

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ “Clothing may seem like a mundane part of our everyday lives. Yet in every culture, clothing is one of the most powerful and ubiquitous forms of visual communication. By using visual clues provided by clothing, people quickly 'place' each other, making guesses about the gender, social status, occupation, ethnic or national identity, and so on of those they encounter. By manipulating the same sets of signals, people can declare their individuality, indicate their beliefs, or signify their membership within various groups through how they dress. At any given time and place there are conventional ways of expressing meaning through one's clothing, but over time these conventions change in response to changed political circumstances, technology, and fashion. This unit will explore the role clothing has played within Chinese culture. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“In China, by Ming and Qing times, clothing indicated not only differences in class and gender, but also ethnicity, as the two major ethnic groups, Han Chinese and Manchu, wore distinct clothes. For periods before photography, our evidence of Chinese clothing styles comes primarily from paintings, supplemented by tomb figurines and archaeological discoveries of actual clothing, mostly of the wealthy and high-ranking. We will take a brief look at what is known of clothing from earlier periods through paintings, then a closer look at the Qing dynasty, which allows us to make use of photographs. We have also included an independent unit on textile technology, primarily on women making silk and cotton.

Photographs, available in some abundance beginning in the 1870s, allow us to see many features of Chinese dress not very well revealed from paintings, including the dress of people of lower social levels. Photographs also allow us to see some of the ethnic distinctions in dress and adornment that resulted from the Manchu conquest in 1644. The most notable change in personal appearance was the requirement that men shave the front of their heads and wear the rest of their hair in a braid, in the Manchu fashion. Although this tended to blur visible distinctions between Chinese and Manchus, in other ways this ethnic distinction was made visible. Manchu women, for instance, were not allowed to bind their feet the way Chinese women did. Although both Manchu men and women were encouraged to wear Manchu dress, rather than adopt Chinese fashions, over time more and more were seen in dress indistinguishable from what Chinese of their class wore.

See Separate Article CHINESE TAPESTRIES AND EMBROIDERY factsanddetails.com ; BEAUTY IN CHINA: FACE SHAPE, WHITE SKIN AND PAGEANTS factsanddetails.com ; HAIR AND HAIRSTYLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CLOTHES IN CHINA: MAO-ERA FASHIONS, SLIT PANTS AND DAYTIME PAJAMA-WEARING factsanddetails.com ; FASHION IN CHINA: WESTERN BRANDS, FOREIGN DESIGNERS AND HAN CLOTHING factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FASHION DESIGNERS factsanddetails.com ; COSMETICS, TATTOOS AND JEWELRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COSMETIC SURGERY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ASIAN PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; University of Washington washington.edu/china; Chinatown ConnectionChinatown Connection ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “5000 Years of Chinese Costumes” by X. Zhou Amazon.com; “Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day” by Valery Garrett Amazon.com; “In the Mood for Cheongsam: A Social History, 1920s-Present” by Lee Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen Amazon.com; “How to Make a Mao Suit” by Antonia Finnane Amazon.com; “Ruling from the Dragon Throne: Costume of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)” by John E. Vollmer Amazon.com; “Chinese Clothing” by Hua Mei Amazon.com; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “Chinese Fashion: From Mao to Now” by Juanjuan Wu and Joanne B. Eicher Amazon.com; “Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation: by Antonia Finnane Amazon.com;

Traditional Cloth-Making and Cloth Materials in China

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: In early times, the two main fabrics were silk and hemp, supplemented by other fibers such as ramie. Beginning in Song times, cotton began to supplant hemp for ordinary clothes, and by Ming times cotton spinning and weaving were important cottage industries. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Silk, the most valued of all fabrics, was made in China from Shang times, if not earlier. Silk makes excellent clothing because it is soft, sheer, lightweight, long-lasting, and can be dyed brilliant colors. It can be made light enough to wear on the hottest of days, but also helps protect against the cold because silk floss makes excellent padding. By the Warring States period, Chinese were making multi-colored brocades and open-work gauzes as well as elaborate silk embroideries. Chinese have long viewed sericulture as a fundamental activity comparable to men's agricultural work. From Song times on governments issued illustrated guides to the sericulture process, both to promote the spread of up-to-date information and to honor the women who worked at making silk.

spinning wheel “From Song times on, cotton became the dominant fiber for ordinary clothes, though hemp and ramie also remained in use. The advantages of cotton were that it was lighter, warmer, and softer than these other fibers. Growing cotton plants was farm work, done primarily by men in areas where the climate and soil were favorable. However, many families that did not grow their own cotton bought unprocessed cotton that they spun themselves, or bought cotton yarn that they wove themselves. Thus, it was very common for women to spin and weave for their families, and in many parts of the country, they also produced for the market.

Making cloth was women's work in China. “Spinning cotton was a demanding task. The spinner has to draw out uniform amounts of the short fibers as she spins so that they can be twisted into a thin, even thread. Cotton was generally woven into simple, flat weaves, using looms like the treadle loom used to weave silk. The loom used by the woman below was much simpler to make and set up. Women in well-to-do households by late Imperial times rarely spun and wove, but needlework was considered a proper occupation for women, and many women spent long hours making lace or doing embroidery.

Silk in China

Used for thousands of years to make clothes in China, silk is a wonderfully strong, light, soft, and sensuous fabric produced from cocoons of the Bombyx caterpillar, or silkworm. Of all the fabrics, silk is regarded as the finest and most beautiful. It has a wonderful sheen — the result of triangle-shaped fibers that reflect light like prisms and layers of protein that build up to a pearly sheen — and can be dyed a host of wonderful colors. The former fashion editor of the Washington Post Nina Hyde wrote, “Designers revel in its feel, its look, even its smell." [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

Silk can be used for all sorts of things. In addition to being woven into fabric, it has been made into cold cream in China, beauty powder and parachutes in the United States, teeth braces in Italy and fishing nets around the world. Bicycle racers say that tires made with silk give them a smoother ride and better traction. Skiers like it because it wicks away moisture. Scientist say it is stronger than steel. In Japan silk artists are revered as national treasures. In India corpses are covered with silk shrouds as a sign of respect. Frugal Ben Franklin splurged on a silk kite for his famous electricity experiments and the first French atomic bomb was dropped from balloon partly made of silk.

Silk production is largely automated and done in factories but the raising of silk worms to make silk is still very much a “cottage industry” done primarily at people’s homes. In some places governments provide anyone who is willing to raise silkworms with 20 kilograms of very small silkworm grubs, which are placed in special boxes in special rooms and fed mulberry leaves gathered from trees near the homes of the people raising them.

Silk brocade is used to make special clothes worn by men and women on New Years's, weddings and celebrations for the birth of a son.

See Separate Article SILK IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SILK, SILK WORMS, THEIR HISTORY AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Imperial Clothing

The members of the court had three sets of clothing: regular, court and ceremonial. Imperial clothes were made with silk, gold, sliver, pearls, jade, rubies, sapphires, coral, lapis lazuli, turquoise, agate, various kinds of fragrant woods, kingfisher feathers and thread made from peacock feathers. Beginning in the Sui dynasty (581-618 A.D.) the emperor appropriated the color yellow and prohibited other people from wearing it based on a purported precedent set by the legendary Yellow Emperor.

Imperial clothing accessories included belts, ceremonial hats, regular hats, hairpins, headdress ornaments, bracelets, thumb rings, fragrance pouches, purses, watches, rosaries, belts (regular, court and ceremonial), necklaces, hat finials, hat decorations, silk purses, shoes for bound feet, hats with jeweled knobs, headbands, silk kerchiefs, fans, rings, buttons, hooks, earnings, brooches and fingernail guards.

Robes were the most visible and decorated garments. They were usually made of silk and featured lavish colors, exquisite stitching and a variety of embroidered decorations and symbols. Most pieces that remain today date to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The Qings (Manchus) were horse people and many of their garments were designed for riding on horses. Many robes have long horseshoe-shaped cuffs because it was considered impolite to show one’s hands and fingers.

Clothing in 19th Century China

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Chinese women's clothing naturally varied by class, season, and region of the country, much as men's did, but dresses, skirts, jackets, trousers, and leggings were all common types of garments. Westerners often commented that Chinese women's clothes did not reveal the shape of their bodies in the way Western women's clothes of the period did. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “It is one of the unaccountable phenomena of Chinese civilization, that this people which is supposed to have been originally pastoral, and which certainly shows a high degree of ingenuity in making use of the gifts of nature, has never learned to weave wool in such a way as to employ it as clothing, The only exceptions to this general statement of which we are aware relate to the Western parts of the Empire, where to a certain extent woollen fabrics are manufactured. But it is most extraordinary that the art of making such goods should not have become general, in view of the great numbers of sheep which are to be seen, especially in the mountainous regions. American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

“It is believed that in ancient times before cotton was introduced, garments were made of some other vegetable fibres, such as rushes. However this may be, it is certain that the nation as a whole is at present absolutely dependant upon cotton. In those parts of the Empire where the winter cold is severe, the people wear an amount of wadded clothing almost sufficient to double the bulk of their bodies. A child clad in this costume, if he happens to fall down, is often as utterly unable to rise, as if he had been strapped into a cask. Of the discomfort of such clumsy dress, we never hear the Chinese complain. The discomfort is in the want of it. It is certain, however, that no Anglo-Saxon would willingly tolerate the disabilities of such an attire, if he could by any possibility be relieved of it.

“One of the most annoying characteristics of Chinese costume, as seen from the foreign stand-point, is the absence of pockets. The average westerner requires a great number of these to meet his needs. He demands breast pockets in his coats for his memorandum books, pockets behind for his handkerchiefs, pockets in his vest for pencil, tooth-pick, etc., as well as for his watch, and in other accessible positions for the accommodation of his pocket-knife, his bunch of keys, and his wallet. If the foreigner is also provided with a pocket comb, a folding foot-rule, a corkscrew, a boot-buttoner, a pair of tweezers, a minute compass, a folding pair of scissors, a pinball, a pocket mirror and a fountain pen, it will not mark him out as a singular exception to his race. Having become accustomed to the constant use of these articles, he cannot dispense with them.

The Chinese, on the other hand, has few or none of such things; if he were presented with them, he would riot know where to put them. If he has a handkerchief, it is thrust into his bosom, and so also is a child which he may have to carry around. If he has a paper of some importance, he carefully unties the strap which confines his trousers to his ancle, inserts the paper, and goes on his way. If he wears outside drawers, he simply tucks in the paper without untying anything. In either case, if the band loosens without his knowledge, the paper is lost — a constant occurrence. Other depositaries of such articles are the folds of the long sleeves when turned back, the crown of a turned-up hat, or the space between the cap and the head. Many Chinese make a practice of ensuring a convenient, although somewhat exiguous supply of ready money, by always striking a cash in one ear. The main dependence for security of articles carried is the girdle, to which a small purse, the tobacco pouch and pipe, and similar objects are attached. If the girdle work loose, the articles are liable to be lost Keys, moustache combs, and a few ancient cash, are attached to some prominent button of the jacket, and each removal of this garment involves care-taking to prevent the loss of the appendages,

Night Clothes and Lack of Underwear in the 19th Century

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “In connection with the heavy clothing of winter, must be mentioned the total lack of any kind of under-clothing. To us it' seems difficult to support existence withbut woollen under-garments, frequently changed. The Chinese are conscious of no such need. Their burdensome wadded clothes hang around their bodies like so many bags, leaving yawning spaces through which the cold penetrates to the flesh, but they do not mind this circumstance, although ready to admit that it is not ideal. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“If the daily dress of the ordinary Chinese seems to us objectionable, his nocturnal costume is at least free from criticism on the score of complexity, for he simply strips to the skin, wraps himself in his quilt, and sleeps the sleep of the just. Nightdress he or she has none. It is indeed recorded that Confucius “required his sleeping-dress to be half as long again as his body." It is supposed, however, that the reference in this passage is to a robe which the master wore when he was fasting, and not to an ordinary night-dress; but it is at all events certain that modern Chinese do not imitate him in his night-robe, and do not fast if they can avoid it.

Even new-born babes, whose skins are exceedingly sensitive to the least changes of temperature, are carelessly laid under the bed-clothes, which are thrown back whenever the mother wishes to exhibit the infant to spectators. The sudden chill which this absurd practice occasions is thought by competent judges to be quite sufficient to account for the very large number of Chinese who before completing the first montth of their existence, die in convulsions. When children have grown larger, instead of being provided with diapers, they are in some regions clad in a pair of bifurcated bags, partly filled with sand, the mere idea of which is sufficient to fill the breast of tenderhearted Western mothers with horror. Weighted with these strange equipments, the poor thing is at first rooted to one spot, like the. frog which was "loaded" with buck shot. In the particular, districts where this custom prevails, it is common to speak of a person, who exhibits small practical knowledge, as one who has not yet been taken out of his "earth-trousers!"

19th Century Chinese Shoes

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: Chinese shoes are made of cloth, and are always porous, absorbing moisture on the smallest provocation. This keeps the feet more or less chilled all the time, whenever the weather is cold. The Chinese have, indeed, a kind of oiled boots which are designed to keep out the dampness, but like many other conveniences, the use of them, on account of the expense, is restricted to a very few. The same is true of umbrellas as a protection against rain. They are luxuries, and are by no means regarded as necessities. Chinese who are obliged to be exposed to the weather do not as a rule think it important, certainly not necessary, to change their clothes when they have become thoroughly wet, and do not seem to find the inconvenience of allowing their garments to dry upon them, at all a serious one. While the Chinese admire foreign gloves, they have none of their own, and while clumsy mittens are not unknown, even in the extreme north they are rarely seen. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: ““A large proportion of Chinese women in the late nineteenth century had their feet bound small while they were children. Sing-song girls, late nineteenth century entertainers had their feet bound as did women in scholar and merchant the families. The shoes that covered bound feet, as well as the leggings over the top of them, were often elaborately embroidered. Manchu women did not bind their feet, but wore elevated shoes that created some of the visual effects of bound feet. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Neiliansheng, one of Beijing time-honored brand, engages in handmade cloth shoes. It was created in 1853, the 3rd year of Emperor Xianfeng in Qing Dynasty by Zhao Ting. “Nei” mean “court” and “liansheng” made the allegorical saying that if guests wore shoes made by Neilianshang, their official career can go up three grades. In the early years, no matter wagoners or court officials wore shoes made by Neiliansheng. It followed that wearing Neiliansheng shoe is a kind of flaunt. Neiliansheng was figured into State-level non-material heritage protection list in 2008. It is the symbol of Beijing culture. [Source: beijing-tour.com]

“In ancient society, shoe was viewed as the symbol of one’s identity, not just an simple clothing. Comparing to clothing, shoe could be named luxury good. When Neiliansheng was founded, it primarily made shoes that only court officials could afford. Neiliansheng registered the size and pattern of each court official’s shoes that was the earliest “customer relationship management profile” in China. When buying shoes once again, it can be made on the basis of the record without being presence by oneself.

“After the revolution of 1911, Neiliansheng set to engaged in satin and ox leather shoes which were popular with people from circles of literature and art. In 1949, the founding of new China, Neiliansheng transformed the direction of management, adding to woman’s shoes, emancipator shoes, etc.. From 1956 to 1958, Neiliansheng turned into development period and became famous band in Beijing.

Traditional Manchu Clothing

Because of the frigid cold in the Manchu homeland in northeast China and the needs of the hunting life, in the past, nearly all the Manchu, both men and women, wore gowns and robes with U-shaped sleeves. After Nurhachi established the "Eight Banner" system in the 17th century, the gown became the costume of "banner man". That is why we called the gown "Cheongsam"("Yijie" in Manchu).

The cheongsam worn by Manchu women was loose and reached to the ankles. It evolved into a tight-fitting dress extending below the knee, with a high neck, narrow sleeves, slender waist and two slits, on the left and right, buttoning down the right side. The dress was known for showing off the figures of eastern women.

The Manchus were a horse-riding people. Wearing the cheongsam made it easier for the women to mount horses. Leonard Yiu, a Malaysian collector of ethnic clothes and jewelry told The Star: “Only later on did the cheongsambecome more curvaceous because of Western influence, and then it became a one-piece costume. “In the old days, the colour red was worn only by the young while the elderly wore blue and black was for widows,” Which era the cheongsam originated from can be deducted from how wide or curvaceous the cut is.

Manchu men have traditionally worn a long gown and mandarin jacket. The traditional costumes of male Manchus are a narrow-cuffed short jacket over a long gown with a belt at the waist to facilitate horse-riding and hunting. Women wore earrings, long gowns and embroidered shoes. Linen was a favorite fabric for the rich; deerskin was popular with the common folk. Silks and satins for noble and the rich and cotton cloth for the ordinary people became standard for Manchurians after a period of life away from the mountains and forests. Following the Manchus' southward migration, the common people came to wear the same kind of dress as their Han counterparts, while the Manchu gown was adopted by Han women generally. [Source: China.org china.org]

According to the Muzeum Narodowe W. Krakowie: : The Qing Dynasty(1644-1911) was characterized by an astounding wealth and variety of robe types. When the Manchu Dynasty seized the power in China in 1644, a new type of clothing appeared. First of all, there was a change in the cut of formal and semi-formal robes worn by both the Manchu and the native Han Chinese. A new type of garments was introduced, the elements of which referred to the Manchu tradition. The robes were fastened along the right side of the body. Additionally, they were equipped with slits at the bottom – the Manchu were entitled to four, while the Hans had the right to two slits at the bottom of the dragon robe. The shape of the sleeves underwent a substantial change - long and wide sleeves were replaced by narrow ones. They also gained a very distinctive division into three parts. The upper part of a sleeve became integrated into the body of the garment. The central dark blue part covered the forearm, while the bottom part consisted of a matixiu cuff in the shape of a horse hoof, which shielded the hand. The Manchu, as an itinerant, nomadic people, wore robes of a cut suitable for horse riding. A matixiu cuff was meant to protect the hand, while the slits at the bottom of the robe, located in the front, at the back and at the sides, facilitated mounting a horse. [Source: Beata Pacana, Head of Department of Far Eastern Art, National Museum in Krakow]

A complete outfit also consisted of a bufu coat with a buzi badge, a piling collar, a ji guan bejewelled headgear, a chao zhu necklace, a jiao dai belt and shoes with high uppers. The robes of Manchu women differed from the clothing of Han women. What is worth emphasising is the fact that the ladies' wardrobes of the two nations borrowed certain elements from each other. A good example is the wide robe sleeves, typical of Han women's clothing, adopted by Manchu ladies for their informal everyday outfits. The main difference lay, however, in the length of the dress and the width of the sleeve. The Manchurians wore long robes with narrow sleeves, while the Han women wore short kaftans with wide sleeves and skirts. It should be noted here that the tradition of foot binding applied only to women of the Han nationality, which resulted in the need for sewing special shoes for them.

Cheongsam (Qi Pao)

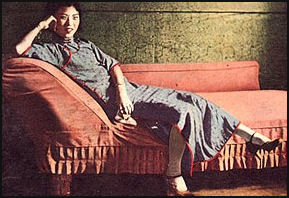

qi pao

The cheongsam, a women’s dress associated with the Chinese, originated with the Manchus. Known as a "qi pao" in Mandarin, the cheongsam is a tight form-fitting Chinese dress with thigh-high slits and a high-collar. Traditionally a dress worn by Manchu women, it received some international exposure in the Suzie Wong film. The slit is supposed to rise no higher than mid thigh. If it goes any higher it is considered sluttish.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ “The modernized Chinese dress commonly worn by women in the early decades of the twentieth century is called the qipao. It is a one-piece dress characterized by an upright ("mandarin") collar, an opening from the neck to under the right arm, and a fairly narrow cut, often with a slit, especially if the skirt reaches below mid-calf. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/=]

“The cut of the qipao changed constantly, as Chinese women's dress became much more subject to fashion than it ever had been before. The mandarin collar, one of the essential features of the qipao, sometimes came to be exaggerated for stylistic effect. In 1930s Shanghai women favored a high collar style. Prior to the twentieth century, collars had never been so exaggerated. Even into the 1990s, the mandarin collar carried messages about "Chineseness." Here we see a stewardess for China Airlines in 1990.

History of the Cheongsam

Cheongsams can be classified into monolayer, cotton and fur types. In the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, the Cheongsam was a gown with patches on the sides and no collar. Its design suited for horse-riding and on-horse shooting methods of the Manchu. When going out for hunting, the Manchu people stored food in the foreparts. This kind of Cheongsam had two prominent traits: the first one was no collar. On the uniform of his bannermen, Nurhachi stipulated: "Each court dress must have a rebato and must be a mere garment in everyday life." That is to say, daily clothes mustn't have a collar and only the court dress can be added with a big shawl-shaped collar. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

The second prominent trait is the so-called horse-hoof sleeve (U-shaped sleeve): a sleeve broad at the top and narrow at the bottom, sort of like the shape of a horse-hoof. The design of the sleeves allowed them to be rolled up in daily life. However, in the course of hunting and fighting, the sleeves could be dropped to cover and warm hands as the gloves. Even when covering the hands the sleeves allowed a mounted warrior to pull his bow and shoot arrows. Thus, they were also called "arrow sleeves" (in Manchu, it is called "Waha"). After Manchu became the rulers of China, "putting down Waha" became a prescribed act of Qing Dynasty protocol. When officers went to court to call on the emperor or other princes and courtiers, they were required to wear a cheongsam and to reach out with their U-shaped sleeves, then bow on bended knees, with both hands on the ground. Customarily, a short jacket was worn outside the cheongsam. This short jacket, whose sleeves were long enough to reach the elbow, had a round collar and was long enough to reach the navel. Because this kind of jacket was first worn for horse-riding and horseback-shooting, it was called "horse jacket"(mandarin jacket). In the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, the mandarin jacket was the "army uniform" for the "Eight Banner" soldiers and later gradually became popular among the common people, which resulted in its usage as a ceremonial dress and its diversity in style and material.

Under the influence of the Han Chinese clothes, with their "large collar and large sleeves", the style of the cheongsam began to change. The arrow sleeves were changed into horn-shaped sleeves and the patches on four sides were changed to patches on two sides. The traditional gown with arrow sleeves was worn only when officers went to court and the common banner men formally went out. After the period of Jiaqing and Daoguang, the arrow sleeves began to die out. By the 1930s, the old-fashioned gown with arrow sleeves had been replaced by the long and cylindric gown with a broad front and large sleeves. Since the 1940s, under the influence of modern styles and new kinds of clothing, the man's cheongsam disappeared and the woman's cheongsam became almost unrecognizable from its original form. The broad sleeves were replaced by narrow sleeves, the length was extended to the ankles, the loose-fitting design suited for riding horses bowed out to a tight-fitting design best suited for appearing sexy in.

Adaptations of Chinese Clothing to Western Styles in the 20th Century

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ As China struggled to define its place within the modern world during the twentieth century, issues of cultural identity were often worked out through clothes. In the first decades of the twentieth century, many of the elite families of China sent their children abroad for study. Western ideas of modernization and industrialization became familiar to a whole generation of young educated elite in China, and many of them came to associate western styles of dress with modernity. While some people fully adopted western style dress, others took to wearing clothes that retained symbolically important elements of traditional dress. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Many of the social, political, and artistic leaders in the early decades of the twentieth century had studied abroad. Song Qingling, the intellectual and political activist of the revolutionary period and the wife of revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen, studied in the U.S. During the political upheaval of the early twentieth century, Chinese men frequently expressed their political allegiances through the clothes they wore.

During the twentieth century certain modes of dress were adopted in an attempt to integrate both traditional Chinese and western cultural influences. The most influential were the qipao for women and the Mao suit. Today, however, many men wear western-style suits, just as women wear western-style clothing.

Ling Long Women's Magazine

According to Columbia University: “Every female student had an issue of Ling long magazine in hand during the 1930s. On the one hand, Ling long imparted the beauty secrets of movie stars, and on the other hand instructed "beautified" and "made up" girls how to keep close guard against the attacks of men, because all men harbor bad intentions. True dating is dangerous, but marriage is even more dangerous, because marriage is the tomb of dating. [Source: Columbia University columbia.edu]

“Between 1931 and 1937, the Sanhe publishing company, located on Nanjing Road in Shanghai, published Ling long magazine, which they called Linloon magazine in English. This pocket-sized weekly stood only 13 centimeters high. According to the first issue, the magazine cost seven fen(7/100ths) of a foreign ounce of silver or 21 copper coins and an extra two fen, February 100ths) of a foreign ounce of silver in other cities. Mr. Lin Zecang was the main backer of the magazine. The editorial board included Mr. Zhou Shexun (entertainment), Ms. Chen Zhenling (women's features), and Mr. Lin Zemin (photography). Both men and women contributed photographs and articles, though the majority of articles appear to have been written by women as indicated by the title nushi (lady) placed next to their name.

“The goal of the magazine was "to promote the exquisite life of women, and encourage lofty entertainment in society." The magazine was divided into two parts, indicated by the front and back covers. The front cover usually featured a photograph of a woman who represented the magazine's ideal of the modern woman, while content on the back cover was usually related to the cinema. The magazine was read in both directions. The articles that read from front to back were usually more instructional and related to women's issues. Articles and photographs that read from the back cover were often concerned with entertainment or unusual feature stories.

“The word ling long (elegant and fine) has an etymology that reaches back to a collection of onomatopoetic words from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) signifying the sounds of pieces of jade clinking together.¹ The classical meaning of ling long also connoted delicate female handiwork. The editors of Ling long magazine redefined this word to mean modern female style. Just like the onomatopoetic sound of the word ling long, articles and photographs on the magazine's pages reverberated like clinking jade. Although certain columns on movies, child-rearing, and legal advice appeared with some regularity, the magazine did not maintain a standard format, and articles often contradicted one another. For example, one article might have showcased the latest movies from Hollywood, while another article attempted to drum up xenophobic patriotism. These different viewpoints came together like clinking pieces of jade in the cacophony that was Ling long magazine.

“In the 1930s, the New Woman swept the globe. Everywhere from New York to Paris to Tokyo, people noted a new type of woman-about-town: urban, sophisticated, educated, and fashionable. In many ways, Shanghai's New Woman was little different from her global counterparts; she bobbed her hair and challenged gender boundaries just like they did. Yet she was also born in a particular modern Chinese context full of contradictions. Reformers idealized the New Woman as free and liberated, an example of China's break from her oppressive and conservative past. Critics of the New Woman, however, suggested that her excessive consumption and unrootedness represented the dangers of unbridled modernity and foreign influences.

“The Ling long woman epitomized the Shanghai New Woman. She lived in both the fantasy world of popular culture and on the streets of everyday Shanghai. Photographs in the magazine ranged from glamorous movie stars to the actual authors of articles, and from society ladies to students. Just as the Ling long woman had multiple identities, the magazine called her a variety of both Chinese and English names: xin nuxing and xin nuzi (new woman); xiandai nuzi (contemporary woman); modeng nuxing (modern woman, modern girl, girl of this age, and girl of today).

“Ling long writers explored what it meant to be an urban, educated woman in the 1930s, although they did not always agree. Marriage was one of the subjects inspiring different viewpoints. Some authors instructed readers about ways to run an ordered, hygienic, modern household, while other writers advocated never getting married. Readers joined in these discussions with letters to the editor on questions ranging from dating to child care. When they opened the magazine, readers walked into the world of the Ling long woman. This world offered readers a fantasy, allowing them to transcend their everyday lives, but it was also a reflection of their lives. The Ling long woman was an elegant movie star; but she was also a good friend — a real urban woman.

Zhongshan Suit (Mao Suit)

In the Mao era, the Chinese wore cheap blue cotton outfits which Westerners call ‘Mao Suits’. The Chinese call them the ‘Zhong-shan-fu’ or ‘Sun Yat-sen suits’, since Sun, the father of Modern China, first advocated wearing simple traditional peasant designs as a classless national uniform. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

The "Zhongshan suit" is named after the great revolutionary pioneer Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yat-sen) . In the last years of the Qing Dynasty, Westerners ridiculed the Chinese as "the sick man of East Asia" and a "pigtail army" in "mandarin jackets and gowns." Sun hated both Western imperialism and the corruption of the Qing Dynasty. He organized a group of ardent patriots to set up the Revive China Society aiming at "expelling the invaders and recovering China." Through the sacrifice of a lot of lives, the 1911 Revolution overthrew the Chinese monarchy and set up the Republic of China. After that, Sun issued a series of policies, decrees and reforms that included "cutting the pigtail" and "changing the clothes". He proposed to "wash away old habits and customs and be new Chinese people." After widely soliciting suggestions and conducing discussions, Sun Zhongshan concluded that "the formal dress must be changed, and the informal dress is at the people's willingness." He helped design a new style of clothes for himself and the Chinese people— a simple set of clothes with the Han people characteristics, called "Zhongshan dress." [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~]

According to the Chinese government: “The Zhongshan suit has absorbed the strong points of the western suit. It has a straight collar and four pockets with buttoned covers. The two pockets below are big enough to hold books. The trousers are designed like this: the front seam is sewed with hidden buttons; on either side there is a hidden pocket. The trousers waist is wrinkled.” Sun took the lead and wore the suit at various kinds of occasions. “Its appearance is symmetrical, beautiful, practical, convenient and in good taste. It can be made of both the high-class dress material and the common cloth. Advocated by Sun the Zhongshan dress became a fashion in the country at that time. The Mao suit was modeled on it. Today, it is still one of the most basic styles of clothing among the Han people.

Craftsmanship of Nanjing Yunjin Brocade Recognized by UNESCO

Craftsmanship of Nanjing Yunjin brocade was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2009. According to UNESCO: In the Chinese tradition of weaving Nanjing Yunjin brocade, two craftspeople operate the upper and lower parts of a large, complicated loom to produce textiles incorporating fine materials such as silk, gold and peacock feather yarn. [Source: UNESCO]

The technique was once used to produce royal garments such as the dragon robe and crown costume; today, it is still used to make high-end attire and souvenirs. Preserved primarily in Jiangsu province in eastern China, the method comprises more than a hundred procedures, including manufacturing looms, drafting patterns, the creation of jacquard cards for programming weaving patterns, dressing the loom and the many stages of weaving itself.

As they ‘pass the warp’ and ‘split the weft’, the weavers sing mnemonic ballads that remind them of the techniques they employ and enhance the cooperative, artistic atmosphere at the loom. The workers view their craft as part of a historical mission since, in addition to creating fabrics for contemporary use, yunjin is used to replicate ancient silk fabrics for researchers and museums. Named for the cloud-like splendour of the fabrics, yunjin remains popular throughout the country.

Traditional Li Textile Techniques Recognized by UNESCO

Traditional Li textile techniques: spinning, dyeing, weaving and embroidering was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2009 and is :in need of urgent safeguarding.” According to UNESCO: The traditional Li textile techniques of spinning, dyeing, weaving and embroidering are employed by women of the Li ethnic group of Hainan Province, China, to make cotton, hemp and other fibres into clothing and other daily necessities. The techniques involved, including warp ikat, double-face embroidery, and single-face jacquard weaving, are passed down from mothers to daughters from early childhood through verbal instruction and personal demonstration. [Source: UNESCO]

Li women design the textile patterns using only their imagination and knowledge of traditional styles. In the absence of a written language, these patterns record the history and legends of Li culture as well as aspects of worship, taboos, beliefs, traditions and folkways. The patterns also distinguish the five major spoken dialects of Hainan Island. The textiles form an indispensable part of important social and cultural occasions such as religious rituals and festivals, and in particular weddings, for which Li women design their own dresses.

As carriers of Li culture, traditional Li textile techniques are an indispensable part of the cultural heritage of the Li ethnic group. However, in recent decades the numbers of women with the weaving and embroidery skills at their command has severely declined to the extent that traditional Li textile techniques are exposed to the risk of extinction and are in urgent need of protection.

Image Sources: University of Washington except men's clothing, Columbia University; Imperial clothing, Toranhouse, Mao-era posters, Landberger, and Western fashions, Perrechon.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021