HAIR IN CHINA

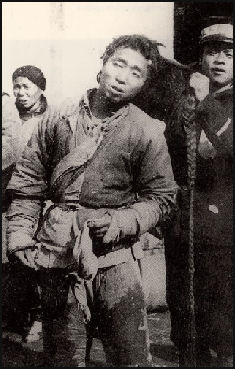

Until early in the 20th century the traditional haircut for a Chinese man was the queue, or braided pigtail, with a shaved forehead. The queue had been forced on the ethnic Han majority as a sign of submission to their Qing Manchu rulers. In 1911, when the Qing dynasty ended, cutting off one’s queue was a symbol of defiance like burning a draft card was in the United States in the Vietnam War era.

Less than 20 percent of women dye their hair, compared to more than 60 percent in Japan and South Korea. Chinese are still a little bit nervous about coloring their hair. In Shanghai people with died hair can not have their identity card pictures taken. It is not uncommon for women with dyed hair to have long roots because of second thoughts they had after dying their hair.

Studies by L’Oreal have found that Chinese women usually wear their hair much longer than Western women. Average length for Chinese women in 50 centimeters. Researchers came across one woman with hair that was 4.3 meters long

See Separate Articles: BEAUTY IN CHINA: FACE SHAPE, WHITE SKIN AND PAGEANTS factsanddetails.com ; HYGIENE IN CHINA: EAR CLEANING AND THE LAST BATHHOUSE IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com ; TOILETS IN CHINA: DIRTY PUBLIC ONES, CLEAN ONES, AND HIGH-TECH ONES factsanddetails.com ; CLOTHES IN CHINA: MAO-ERA FASHIONS, SLIT PANTS AND DAYTIME PAJAMA-WEARING factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CLOTHES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FASHION IN CHINA: WESTERN BRANDS, FOREIGN DESIGNERS AND HAN CLOTHING factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FASHION DESIGNERS factsanddetails.com ; COSMETICS, TATTOOS AND JEWELRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COSMETIC SURGERY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ASIAN PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China Hair manufactures, Suppliers and Vendors Contact List” Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History” by Victoria Sherrow Amazon.com; “The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty’ by Cho Kyo and Kyoko Iriye Selde Amazon.com; “Buying Beauty: Cosmetic Surgery in China” by Wen Hua Amazon.com

Asian Hair

Individual strands of Chinese women’s hair are circular and wider and more resistant to breaking than the oval hairs of Western women. Chinese hair has higher pigment concentrations that makes it glossier and shinier than the hair of Western women and less likely to turn white. Chinese hair is less dense than Western hair with fewer hairs per square centimeter of scalp.

When stripped of its natural pigment, Asian hair has reddish undertones while European hair has yellow-orange undertones. As a result hair dyes for Asian women are made with green that cancels out red while those for European women are made with violet that cancels out the yellow-orange undertones.

More than 150 million Chinese men aged 25 to 35, or about 40 percent of the male population in that age group, suffer from baldness or significant hair loss. Fast-paced living and long periods of stress are blamed for high rates of hair loss.

Many that have hair that goes grey or white prematurely dye it.

Hairstyles and Hats in 19th Century China

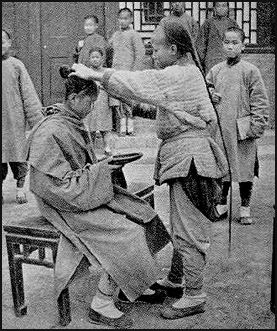

19th century Sidewalk barber

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “To us it certainly appears singular that a great nation should become reconciled to such an unnatural custom as shaving off the entire front part of the head, leaving that exposed, which nature evidently intended should be protected. But since the Chinese were driven to adopt this custom at the point of the sword, and since, as already remarked, it has become a sign and a test of loyalty, it need be no further noticed in this connection, than to call attention to the undoubted fact that the Chinese themselves do not recognize any discomfort from the practice, and would probably be exceedingly unwilling to revert to the Ming dynasty tonsure. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

The same considerations do not apply to the Chinese habit of going bareheaded at almost all seasons of the year, and especially in summer. The whole nation moves about in the blistering heats of the summer months, holding one arm aloft, with an open fan held at such an angle as to obstruct a* portion of the rays of the sun. Those who at any part of their lives hold an umbrella in their hands to ward off heat, must constitute but a most insignificant fraction of the population. While men do often wear hats upon certain provocation, Chinese women, so, far as we have observed, have no other kind of head-dress than that which, however" great its failure viewed from the unsympathetic Western stand-point, is intended to be ornamental. One of the very few requisites for comfort, according to Chinese ideas, is a fan, that is to say, in the season when it is possible to use such an accessory to comfort. It is not uncommon in the summer to see coolies, almost or quite devoid of clothing, struggling to track a heavy salt-junk up stream, vigorously fanning themselves meanwhile. Even beggars frequently brandish broken fans.

Beauty Shops and Barbers in China

The Chinese can be very fussy about their hair. Many towns and neighborhoods are full of beauty parlors. According to the China Association of Fragrance, Flavor and Cosmetic Industries, the number of beauty shops, barber shop and spas increased from about 100,000 in 1985 to 1.2 million in 2000. Prostitutes often work out of beauty parlors, hairdressers, and barbershops.

In some Chinese barbershops, barbers wearing surgical masks shave every inch of their customer's face: the hairline, earlobes, nose and even eyelids. Chinese beauty salons offer dry shampooing in which the hair is washed in the styling chair. A few drops of water are added to the hair and the scalp is rubbed and scratched for up to an hour to achieve a good head of lather.

In the Mao, the government told people how to wear their hair. During the Cultural Revolution women had their hair cut short and wore Mao-style caps, often looking more like boys than women. Some people indulged themselves. In the northeastern town of Dalian men as well as women had their hair curled at the "Red Star Cut and Perm."

In Beijing, Chinese tourists often get a quick haircut or a shave from a street barber before visiting a site like the Forbidden City because they want to look their best for photographs. Describing a shave by an outdoor barber in Beijing, Michael Finkel wrote in the New York Times: "Apparently, the Chinese have a dislike of facial hair. I received the shave of my life, which included a precise razoring if all the tiny hairs edging my ears, a freshly sharpened knife deftly applied by my eyelids (I'd been instructed to shut my eyes) and a full forehead defoliation. I think I was fortunate to escape with my eyebrows intact." [Source: Michael Finkel, New York Times, March 19, 2000]

Boutique spas in Shanghai offer 13 types of facials and a chocolate pedicure for $48.

Dry Shampoo and Cut

1990s sidewalk barber

Describing a haircut at a reasonably nice salon in Beijing Liz Clarke wrote in the Washington Post, “With his white smock and pompadour, the Chinese hair cutter showed me an entirely new technique...From the list of sources printed in Mandarin and English, I had pointed to ‘shampoo and haircut.” Then I took a seat in the chair, expecting a consult. Instead he squirted a bottle of shampoo on my perfectly dry hair without dribbling a bit on my neck.”

”He worked the shampoo into a lather. Then he squirted more — enough shampoo, its seemed, to clean the Yangtze River...A mountain of suds in my hair, I was led to the sunk for a rinse. Then back in the chair for the cut. His hands were sure and deft despite the inch-long fingernails protruding from his pinkie fingers...I feel like a new woman now, with a crisp bob that falls just short of my shoulders. And the cost: 60 yuan — about $9.”

Wigs and Hair in China

China is one of the world’s largest exporters of wigs, toupees and hair pieces and one of the largest importers of hair. In 2002, it supplied the United States with 96 percent of the 10.7 tons of hair it imported. The same year China imported 3.3 tons of hair from India, most of it collected at temples where pilgrims have their head shaved as part of a purification ritual. That hair, regarded as the best in the world, is treated at about 200 hair processing plants in China and re-exported to the United States and Europe.

In the late 2000s there was an increase in demand for hair extensions in Japan, which in turn increased the demand and prices of hair in China. Japan imported 178 tons of hair, enough to make 3.56 million extensions, from China in 2007, up from 26 tons in 2002. Prices increased 50 percent alone between 2007 and 2008.

Juancheng County in southern Shandong Province is the center of the Chinese hair industry. There are 84 hair-related factories. Around 30,000 people are employed in the industry and one third of the county’s revenues come hair. In 2002 Juancheng launched the People’s Hair Scenery Festival. Xuchang County in Henan Province is another big wig producer. One large company there is listed on China’s stock market. Wigs sold in China are made silk, synthetic fibers or hair from peasant women in Tibet and Sichuan, who are paid $24 a kilogram fo their hair, and fashioned by Korean-made machines.

China has been exporting hair to the West since the 19th century. The practice continued in the Mao era and was the source of much of hair in 1960s when Jacky Kennedy set off a wig boom in the United States among women who wanted to imitate her look. As the wig boom subsided among white women in United States in the 1980s the slack was picked up by African and black American women who wanted hair for hair extensions, braids, weaves and curls.

Hair for Sale

Cutting of the queue in 1911

Hair, often called “people’s fur,” is collected by some 40,000 dealers who scour the country for hair, sometimes making deals to purchase it from other countries. The dealers typically have agreements with hair shop owners. Some go directly to the source. In the hutongs in Beijing, vendors shout out “Looong haaaiir! Loooong haaaair! and pay $10 a pop for long pony tails and reject hair that is deemed too short. Long hair is particularly valuable because it can be used in expensive long hair wigs. Sometimes young women with long hair are paid to have it cut. The dealers sometimes hoard the hair and wait for prices to go up.

Describing a hair collection operation at a village in Shandong, Akiko Kano wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “A small, beat up truck trundled between poor households, blasting out warbling music. Suddenly a girl jumped in front of the truck, shouting, “stop!” She wore no make up and looked very young. On her head stood a great mass of black hair, arranged in a shape reminiscent of soft-serve ice cream. Her hair when undone, almost reached the ground. The driver got out of the truck and began to cut the girls’ hair with scissors. When he was done, he gave the girl a small amount of money. She was left with a rather masculine -looking hairstyle.”

Extensions worn in Japan wear out after three months of use. Hair grows around two centimeters a month. That means it takes about three years to grown hair that is 65 centimeters in length, the minimum wanted by hair brokers. Hair is often bleached and then dyed black or brown before it is processed or exported.

Chinese Woman’s Soccer Team Loses Match Because of Hair Dye

Female soccer players in China can be disqualified from a match if they wear jewelry or have dyed hair. Male players are generally barred from having long hair. In 2020, a Chinese university team argued that an opposing player’s hair was not “black enough, ” according to the rules, and her team forfeited the match. Yan Zhuang wrote in New York Times: “Forget skill, training or even luck. If you’re a female soccer player in China, sometimes victory or defeat comes down to the color of your hair, as one university team recently found out the hard way. The women’s teams at Fuzhou University and Jimei University were supposed to face off at an intercollegiate tournament last week in China’s southeast. But they were barred from participating because players from both teams had dyed hair, which was against the rules. [Source: Yan Zhuang, New York Times, December 10, 2020]

“Photos from the tournament show all the players with either black or dark-brown hair, but apparently those were the wrong shades. The Fujian Province Department of Education’s rules governing university soccer state that players will be disqualified from a match if they wear accessories or jewelry, or have “strange” hairstyles or dyed hair. So coaches rushed to buy black hair dye to meet the requirements and assembled seven players with dark hair from each team to compete, according to state-run media. But the Jimei University team members argued that one of their opponents still did not have “black enough” hair, and she was ordered to leave the game. One player short, the Fuzhou University team forfeited the match.

“Under China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, the Communist Party’s creeping interference on the smallest details of Chinese life is being felt more and more. Censors have blurred the bejeweled earlobes of young male pop stars on television. Women in costumes at a video game convention were told to raise their necklines.

“With soccer a national priority under Mr. Xi, the crackdown has spread to sports. Last year, members of the men’s national soccer team were forced to play in long sleeves in stifling heat at the Asian Cup in Abu Dhabi after the government banned the display of tattoos during matches. The ban applied both to the national team and to domestic soccer players all the way down to university leagues. Other players have had to put bandages over tattoos and or have been barred from playing for wearing necklaces on the field.

Dyed hair

“The episode last week sparked intense debate on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging platform, where the hashtag “female soccer team lost due to too many players having dyed hair” has been viewed 180 million times. Many noted the lagging performance of China’s national teams and opined that the focus should be on improving the skills of players rather than on superficial aspects of the game. One user characterized the episode surrounding the women’s teams as “nitpicking over irrelevant details, ” and added, “This shows that our soccer culture is not tolerant or forgiving enough.” Some users also noted that the rules were simply out of touch because it is all too common for university-age women in China to dye their hair — much as the American soccer star Megan Rapinoe did with a shade of violet while helping the U.S. team take the 2019 World Cup title. But others supported the Chinese officials’ decision to enforce the rules. “This kind of requirement is right, because these players often become idols for schoolchildren and their conduct can influence other people, ” one social media user wrote.

“The Fujian Education Department’s rules governing university soccer do not apply only to female players: Male players are barred from having long hair. But some male professional soccer players have gotten more adventurous with their hair colors and styles. Wei Shihao, a player for Guangzhou Evergrande, made headlines last year when he sported dreadlocks with white tips, and recently when he dyed his hair blond.

In a post on its website about the forfeited match, Fuzhou Universityt said: “Although the match against Jimei University on November 30 was unable to go ahead for some reason and we were declared to have lost, the outstanding strength and determination of the whole team was clear to see. They learned a lesson from the event and adjusted their attitudes.” The following day, the post revealed, the team won its match against another university team, and it came in second over all in the competition. “Apparently, the players had achieved the right shade of black, after all.

Image Sources: University of Washington Excepet Mao-era poster, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/, dyed hair, Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china , modern sidewalk barber, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Wikicommons; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021