SILK

Qing-era silk dress Silk is a wonderfully strong, light, soft, and sensuous fabric produced from cocoons of the Bombyx caterpillar, or silkworm Of all the fabrics, silk is regarded as the finest and most beautiful. It has a wonderful sheen — the result of triangle-shaped fibers that reflect light like prisms and layers of protein that build up to a pearly sheen — and can be dyed a host of wonderful colors. The former fashion editor of the Washington Post Nina Hyde wrote, “Designers revel in its feel, its look, even its smell." [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984, ╟]

Silk can be used for all sorts of things. In addition to being woven into fabric, it has been made into cold cream in China, beauty powder and parachutes in the United States, teeth braces in Italy and fishing nets around the world. Bicycle racers say that tires made with silk give them a smoother ride and better traction. Skiers like it because it wicks away moisture and scientist say silk is stronger than steel. In Japan silk artists are revered as national treasures. In India corpses are covered with silk shrouds as a sign of respect. Frugal Ben Franklin splurged on a silk kite for his famous electricity experiments and the first French atomic bomb was dropped from balloon partly of silk.╟

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Silk is almost miraculous in its strength, light weight and insulating characteristics. It provides a medium for writing and reproducing visual images; it is likely that the knowledge of silk processing led to the discovery of how to make paper from plant fibers, another Chinese invention. Early examples of silk fabric preserved in Chinese burials are decorated with "auspicious symbols" suggesting that the fabric had religious significance connecting humans with the natural and supernatural world. [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad ]

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: ““Silk has been long thought to be a special type of cloth; it keeps one cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It is extremely absorbent, meaning it uses color dyes much more efficiently than cotton, wool, or linen. It shimmers. It drapes upon the body particularly well. Silk is strong enough to be used for surgical sutures — indeed, by weight it is stronger than steel and more flexible than nylon. It is also fire and rot resistant. All these natural characteristics make silk ideal as a form of adornment for people of importance, for kimonos in Japan and wedding saris in India, for religious ritual, for burial shrouds in China and to lay on the graves of Sufis in much of the Muslim world...Silk is still relatively rare, and therefore expensive; consider that silk constitutes only 0.2 percent of the world's textile fabric. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD: PRODUCTS, TRADE, MONEY AND SOGDIAN MERCHANTS factsanddetails.com; END OF THE SILK ROAD AND RISE OF THE EUROPEAN SILK INDUSTRY AND SILK ROAD TOURISM factsanddetails.com; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; SILK IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; RURAL LIFE IN CHINA 14 ; VILLAGES IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: History of Silk silk-road.com ; Wikipedia article on silk Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Silkworms Wikipedia ; Wormspit wormspit.com ; Raising Silkworms silkwormshop.com ; Making Silk chateau-michel.org ; Silk Making with Pictures designboom.com ; Silk Making in Shanghai galenfrysinger.com ; Silk Association of Great Britian silk.org.uk ; Silk Info texeresilk.com ; About Silkworms silkwormmori

On Agriculture: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Wconomy Watch.com economywatch.com ; Products List and Links made-in-china.com ; China’s Ministry of Agriculture Data english.agri.gov.cn ; End of Agriculture in China, NPR Report npr.org ; Library of Congress Report from the 1980s lcweb2.loc.gov ; Can China Feed Itself? iiasa.ac.at/collections ; Essay on Agriculture and WTO Membership mtholyoke.edu ; Changing Agriculture and Farmers sociology.cass.cn

World’s Top Silk Producing Countries

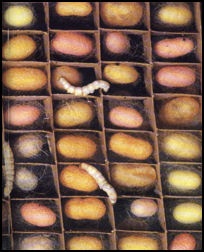

Silkworm cocoonsWorld’s Top Producers of Raw Silk (2019): 1) China: 136000 tonnes; 2) India: 30000 tonnes; 3) Vietnam: 1778 tonnes; 4) Thailand: 1600 tonnes; 5) Uzbekistan: 1500 tonnes; 6) Iran: 900 tonnes; 7) Brazil: 488 tonnes; 8) North Korea: 400 tonnes; 9) Tajikistan: 200 tonnes; 10) Indonesia: 120 tonnes; 11) Kyrgyzstan: 50 tonnes; 12) Afghanistan: 50 tonnes; 13) Cambodia: 25 tonnes; 14) Japan: 19 tonnes; 15) Madagascar: 14 tonnes; 16) Turkey: 13 tonnes; 17) South Korea: 3 tonnes; 18) Taiwan: 1 tonne; 19) Egypt: 1 tonne. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org. A tonne (or metric ton) is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kilograms (kgs) or 2,204.6 pounds (lbs). A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lbs.]

World’s Top Producers of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2020): 1) China: 400000 tonnes; 2) India: 200000 tonnes; 3) Uzbekistan: 20942 tonnes; 4) Vietnam: 14937 tonnes; 5) Thailand: 11400 tonnes; 6) Iran: 6000 tonnes; 7) North Korea: 2857 tonnes; 8) Brazil: 2742 tonnes; 9) Tajikistan: 1429 tonnes; 10) Indonesia: 857 tonnes; 11) Afghanistan: 500 tonnes; 12) Azerbaijan: 447 tonnes; 13) Kyrgyzstan: 357 tonnes; 14) Cambodia: 280 tonnes; 15) Madagascar: 100 tonnes; 16) Turkey: 90 tonnes; 17) Japan: 80 tonnes; 18) Nepal: 35 tonnes; 19) South Korea: 21 tonnes; 20) Egypt: 7 tonnes

World’s Top Producers (in terms of value) of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2019): 1) China: Int.$1759311,000 ; 2) India: Int.$735021,000 ; 3) Thailand: Int.$240582,000 ; 4) Uzbekistan: Int.$91825,000 ; 5) Vietnam: Int.$28947,000 ; 6) Iran: Int.$25777,000 ; 7) Brazil: Int.$13133,000 ; 8) North Korea: Int.$9026,000 ; 9) Indonesia: Int.$3115,000 ; 10) Azerbaijan: Int.$2767,000 ; 11) Tajikistan: Int.$2419,000 ; 12) Afghanistan: Int.$2148,000 ; 13) Kyrgyzstan: Int.$1693,000 ; 14) Cambodia: Int.$1207,000 ; 15) Madagascar: Int.$434,000 ; 16) Japan: Int.$395,000 ; 17) Turkey: Int.$348,000 ; 18) Nepal: Int.$137,000 ; 19) South Korea: Int.$56,000 ; 20) Egypt: Int.$21,000 ; [An international dollar (Int.$) buys a comparable amount of goods in the cited country that a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.]

Top Silkworm-Cocoon-Producing Countries in 2008 (Production, $1000; Production, metric tons, FAO): 1) China, 1247820 , 370003; 2) India, 259679 , 77000; 3) Uzbekistan, 79252 , 23500; 4) Brazil, 27671 , 8205; 5) Iran (Islamic Republic of), 20234 , 6000; 6) Thailand, 16862 , 5000; 7) Viet Nam, 10117 , 3000; 8) Democratic People's Republic of Korea, 1 , 1400; 9) Romania, 3372 , 1000; 10) Afghanistan, 1686 , 500; 11) Japan, 1288 , 382; 12) Cambodia, 1011 , 300; 13) Kyrgyzstan, 505 , 150; 14) Turkey, 421 , 125; 15) Egypt, 404 , 120; 15) Spain, 404 , 120; 17) Bulgaria, 168 , 50; 17) Italy, 168 , 50; 17) Lebanon, 168 , 50; 17) Madagascar, 168 , 50.

Silk in China

The Chinese character for happiness is a combination of the symbols for white, silk, and tree. In ancient China silk was used as currency and a reward, and the imperial court established silk factories to weave ceremonial garments and gifts to foreign dignitaries.

More than ten million farmers in China raise silk and nearly half a million people are employed in silk-fabric production. In 1982, China exported 36,000 tons of silk, primarily to markets in the United States, Japan and Europe. [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

China produces 80 percent of the world's tussad (wild silk) and 50 percent of the world's supply of silk yarn. Italy and France produced better finished products than China. And the most prized silk of all is Chinese silk yarn made into fabrics at Italian mills.

A third of China's raw silk, brocade and satin comes from the Zhejiang Province, the "Land of Silk." Describing the city of Suzhou, near Zhejiang in the Jiangsu Province, in 1276, Marco Polo wrote: "They have vast quantities of raw silk, and manufacture it, not only for their own consumption, all of them being clothed in dresses of silk, but also for other markets.

Early History of Silk

8th century Sogdian silk According to a Chinese legend, silk was discovered in 2460 B.C. by the 14-year-old Chinese Empress Xi Ling Shi who lived in a palace with a garden with many mulberry trees. One day she took a cocoon from one of the trees and accidently dropped it in hot water and found she could unwind the shimmering thread from the pliable cocoon. For hundreds of years after that only the Chinese royal family was allowed to wear silk. Xi Ling Shi is now honored as the goddess of silk.

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “Silk cultivation and production is such an extraordinary process that it is easy to see why its invention was legendary and its discovery eluded many who sought its secrets. The original production of silk in China is often attributed to Fo Xi, the emperor who initiated the raising of silkworms and the cultivation of mulberry trees to feed them. Xi Lingshi, the wife of the Yellow Emperor whose reign is dated from 2677 to 2597 B.C.E., is regarded as the legendary Lady of the Silkworms for having developed the method for unraveling the cocoons and reeling the silk filament. Archaeological finds from this period include silk fabric from the southeast Zhejiang province dated to about 3000 B.C.E. and a silk cocoon from the Yellow River valley in northern China dated to about 2500 B.C.E. Yet silk cloth fragments and a cup carved with a silkworm design from the Yangzi Valley in southern China dated to about 4000―5000 B.C.E. suggest that sericulture, the process of making silk, may have an earlier origin than suggested by legend. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

The earliest evidence of silk was found at the sites of Yangshao culture in Xia County, Shanxi, where a silk cocoon was found cut in half by a sharp knife, dating back to between 4000 and 3000 B.C. The species was identified as Bombyx mori, the domesticated silkworm. Fragments of primitive loom can also be seen from the sites of Hemudu culture in Yuyao, Zhejiang, dated to about 4000 B.C.. The earliest example of silk fabric is from 3630 BC, and was used as wrapping for the body of a child. The fabric comes from a Yangshao site in Qingtaicun at Rongyang, Henan. Scraps of silk were found in a Liangzhu culture site at Qianshanyang in Huzhou, Zhejiang, dating back to 2700 B.C.. Other fragments have been recovered from royal tombs in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 B.C.). [Source: Wikipedia]

Some of the oldest known silk fibers have been found in Jiahu near the Yellow River in Henan Province in central China. Jiahu is regarded by many as China’s oldest culture and settlement.. Archaeology magazine reported in 2017:” Soil samples taken from beneath skeletons in two tombs that date back 8,500 years reveal traces of silk proteins, indicating that the deceased may have been dressed in silk garments when they were buried. This new evidence pushes back the first known silk production technology by nearly 3,500 years. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2017]

Evidence of silk weaving includes impressions found on a bronze urn dated to 1330 B.C. The provincial museum in Hangzhou houses silk threads and embroidery knots that may be 4,500 years old. In 1982 brickyard workers stumbled across a ancient tomb from 300 B.C. with remarkably well preserved silk quilts and gowns. Tombs in the Hubei province dating from the 4th and 3rd centuries BC contain outstanding examples of silk work, including brocade, gauze and embroidered silk, and the first complete silk garments.”

The secret of making silk remained in China for thousands of years. Imperial law decreed death by torture to anyone who disclosed it. No one is sure when the secret first seeped out of China, but it is known to have reached Japan by way of Korea by the A.D. 4th century and said to have been brought there by four Chinese girls. It is also said that silk was brought to India by a Chinese princess who hid eggs and mulberry seeds in the lining of her headdress.

See Silk Road.

Ancient Silk Production

According to UNESCO: “Silk is a textile of ancient Chinese origin, woven from the protein fibre produced by the silkworm to make its cocoon... Regarded as an extremely high value product, it was reserved for the exclusive usage of the Chinese imperial court for the making of cloths, drapes, banners, and other items of prestige. Its production was kept a fiercely guarded secret within China for some 3,000 years, with imperial decrees sentencing to death anyone who revealed to a foreigner the process of its production. [Source: UNESCO unesco.org/silkroad ]

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Some time probably in the fourth millennium B.C., the Chinese learned the secret of unraveling the fine, rounded filament of the cocoons spun by a worm (Bombyx mori) which fed on the leaves of mulberry trees. There are other species of silk worms (for example, ones native to India), which produce a flatter filament or chew through the cocoon, leaving short fibers. [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “ Indian tussah silk dates back possibly to 2500 B.C.E. to the Indus Valley civilization and is still produced for domestic consumption and foreign trade in various forms. Since traditional Hindu and Jain production techniques do not allow for the killing of the pupae in the cocoon, moths are allowed to hatch, and the resultant filaments are shorter and coarser than the Chinese variety. The ancient Greeks, too, knew of a wild Mediterranean silk moth whose cocoon could be unraveled to form fiber. The process was tedious, however, and the result also not up to the quality of mulberry-fed Bombyx mori. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: ““Many insects from all over the world — and spiders as well — produce silk. One of the native Chinese varieties of silkworm with the scientific name Bombyx mori is uniquely suited to the production of superbly high-quality silk. This silkworm, which is actually a caterpillar, takes adult form as a blind, flightless moth that immediately mates, lays about 400 eggs in a four- to six-day period, and then abruptly dies. The eggs must be kept at a warm temperature for them to hatch as silkworms or caterpillars. When they do hatch, they are stacked in layers of trays and given chopped up leaves of the white mulberry to eat. They eat throughout the day for four or five weeks, growing to about 10,000 times their original weight.

Silk Road

Silk and the Silk Road

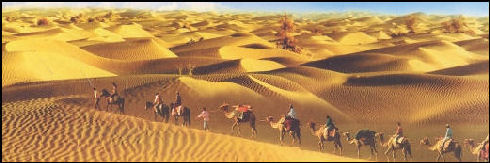

Silk was prized as a trade item and was ideal for overland travel because it was easy to carry, took up little space, held up over time, weighed relatively little but was high in value. By weight silk was worth as much as gold and often used as a form of money and could be given as bribes and as tribute.

The silk carried on the Silk Road came in the form of rolls of raw silk, dyed rolls, cloth, tapestries, embroideries, carpets and clothes. Much of the silk that left China was in the raw form and it was turned into embroidered cloth and art work in cities such as Samarkand in Central Asia, Baghdad in the Middle East and Lhasa in Tibet.

In the Silk Road era, silk was used for book coverings, wall hangings, clothes, purses, slippers and boots. It was decorated with floral patters and images of birds and mythical beasts such as winged lions and dragons with elephantine snouts stitched with gold or silver thread. The origin of objects could be determined by examining figures, weaves and threads.

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Although it was only one of many products traded, silk perhaps best encompasses the history of economic and cultural exchange across Eurasia along the "Silk" Road. The value of silk gave it particular appeal as a political and religious symbol, it was widely accepted as a currency, and it served as a medium for artistic exchange. The complex history of silk is both well documented and in some ways but poorly known. [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

See Separate Articles on the Silk Road and Exploration factsanddetails.com]

Early Silk Trade

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Discoveries in Egyptian tombs indicate that some Chinese silk made its way to the Mediterranean world at least as early as 1000 B.C. The routes of transmission presumably were the same which developed more extensively in later centuries, overland across the heart of Asia or via the coastal trade around Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean. In most histories though, the real beginning of the "Silk" Road dates to the establishment of the Xiongnu (Hun) nomadic empire on the northern borders of China around 200 B.C. and the development of a relationship between the Xiongnu and the Han Imperial court whereby large quantities of silk were shipped to the nomads to buy peace along the frontiers and ensure the supply of horses and camels for the Chinese armies. This transmission of silk into Inner Asia established the pattern for later centuries, the nomads receiving both finished garments, embroidered or woven with Chinese designs, and raw silk yarn and unfinished cloth. [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“Striking evidence of the Xiongnu's appreciation for the silk has been uncovered in the royal burials at Noin-Ula in Mongolia, dating from the second and first century B.C. The fabrics discovered there include woolens and silk embroidered with silk thread or decorated with silk appliques. Of particular interest is the fact that some of the embroidery depicts faces of individuals who have distinctly "western" features, suggesting the possibility that even at this early stage in the history of the Silk Road weavers from further west were employed by the Xiongnu in processing the "raw materials" imported from China. Such a pattern of the exchange of craftsmen involved in silk processing recurs throughout the history of the Silk Road. We cannot be certain who were the "westerners" depicted in the Noin-Ula embroidery, but there is substantial archaeological evidence even from some centuries earlier documenting the presence in Inner Asia of people with "Indo-European" features and documenting as well interactions between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and the peoples of the steppe regions of Southern Siberia and Mongolia. *\

“The quantities of Chinese silk shipped on a regular basis to the nomads down through the centuries were substantial, often tens of thousands of bolts of silk or packages of silk floss annually. Possibly the peak of this exchange was reached in the T'ang Dynasty in the eighth and early ninth centuries, when as much as one-seventh of the government's annual tax revenue paid in silk was being used to obtain horses for the imperial army. The silk was important to the nomads, who acquired a taste for the luxury it provided. The process of building and maintaining a nomadic confederacy of the numerous tribes in the steppe was dependent in part on the ability of the nomadic ruler to distribute on a regular basis to his allies and relatives luxurious silks. Yet it seems quite clear that the quantities of silk sent to the nomads far exceeded their needs. The surplus has to have provided one of the important means for the nomads to acquire other goods they sought by trading the silk to those further west. Thus it is no coincidence that Roman sources from around the first century B.C. begin to indicate a sizeable influx of silk into the Roman Empire, within a century or so following the initial agreements by which the Han supplied the Xiongnu with silk on an annual basis. By the first century CE, Roman moralists complained that the taste for the luxury (and for other luxuries imported from the east, such as spices) was bankrupting the empire. *\

Silk Production in Europe

Silk dying and weaving developed in ancient Syria, Greece and Rome but the silk itself always came from the East. Silk production first made it way to the West in the A.D. 6th century when monks working as spies for Byzantine Emperor Justinian brought silkworm eggs from China to Constantinople in hollowed out canes. Bursa in present-day Turkey and Athens, Theves, Corinth and Argos in present-day Greece all became silk producing areas.

Mulberry trees

Silk production spread to Italy and France and continued through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and Industrial Revolution but was devastated by a silkworm plague in 1854. Louis Pasteur discovered the cause and developed a treatment. The Italian industry recovered but the French industry never did.

In recent years the silk industry has been hurt by the development of synthetic fibers.

Silkworms

Silkworms are not worms but caterpillars, the larvae of moths. They belong to two families: Bombycidae (the commercial silkworm), which feed on mulberry leaves, and Saturniideae (the so called wild silkworms), which primarily eat oak leaves.

All butterfly and moth caterpillars produce silk, as do spiders, but only silkworms produce the lustrous, long fiber that is made into commercial silk. Most commercial silks comes from the Bombyx mori, a silkworm that originated in China. Over 300 varieties of this caterpillar are found in China today. More than 600 varieties are found in Japan. Tussah wild silkworms are bright yellow in color and may reach a length of six inches. Their silk is strong but rough and doesn't die very well.

Richard Kurin at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “Many insects from all over the world — and spiders as well — produce silk. One of the native Chinese varieties of silkworm with the scientific name Bombyx mori is uniquely suited to the production of superbly high-quality silk. This silkworm, which is actually a caterpillar, takes adult form as a blind, flightless moth that immediately mates, lays about 400 eggs in a four- to six-day period, and then abruptly dies. The eggs must be kept at a warm temperature for them to hatch as silkworms or caterpillars. When they do hatch, they are stacked in layers of trays and given chopped up leaves of the white mulberry to eat. They eat throughout the day for four or five weeks, growing to about 10,000 times their original weight. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

Domesticated silkworm moths have been described as "machine devoted to sex" but are essentially flightless so they must search for mates on foot. If necessary they can travel a considerable distance to find a mate. Male silkworm have such a good sense of smell they can smell females 6½ miles away.

After several hours of mating the female lays 300 to 500 eggs, each not much large than a pinhead, then dies within two or three days. The eggs, which require cold weather to trigger development, hatch anywhere from six weeks to 12 months after being deposited.

The eggs hatch producing grubs that develop into larvae (the caterpillars or silkworms) and spend several weeks munching on mulberry leaves and molting. When they outgrow their skin, the simple squeeze out it, jaw and all, and grow a new one. After tossing off their skin for the forth time they begin find a place and being making their cocoon. After about a month they emerge as moths.

Sericulture

The process or raising silkworms and unwinding their cocoons is called sericulture. Silkworms have to be carefully taken care of: they need to be fed regularly and maintained in a carefully controlled environment. It is a labor intensive industry, generally requiring lots of people willing to work for low wages.

Making silk begins when a female silkworm lays her eggs. In China, the eggs are often produced in special institutions regulated by the government to make sure the eggs are healthy. Workers speed up the hatching process by soaking the eggs in chemicals. About a week after the eggs are laid, silkworm grubs emerge. They are around a quarter of an inch in length and the width of a hair. They squirm into huge flat baskets, filled with mulberry leaves and are placed on shelves.

Silk thread

The silkworms spend their 25- to 28-day long lives in baskets, or trays, munching on mulberry leaves. Even though the baskets are open the silkworms do not try to escape. Silkworms are extraordinary eating machines. They can eat and breath at the same time, taking in oxygen from nine holes on the sides of their body, and make eating sounds compared with fizzing Alka-Seltzer. They are especially hungry right before they begin making their cocoons. In some cases they are fed ten times a day and their body weight increases 10,000 times in their short lives.

The main raw material other than the silkworms themselves are the leaves from mulberry trees. In the past, mulberry trees were raised on hilly areas while lowlands were devoted to rice growing, and peasants had to spend a lot of time picking leaves off the trees. These days the leaves are produced on trees grown on plantations very far from where the silkworms are raised and trucked in to wear the silkworms are raised.

A hundred kilograms of mulberry leaves yields 25 silkworm cocoons. The caterpillars used to make the kimono devoured over 135 pounds of mulberry leaves. The 8,000 worms supply silk for ten blouses, consume approximately 350 pounds of mulberry leaves. The leaves from plantation-grown mulberry trees are plucked, chopped and prepared for the silkworms. In Japan, they are mixed with beans and agar into a concoction that looks like sweet bean paste. After the trees are stripped they are pruned and sprayed for next year's crop.

Silkworm Care

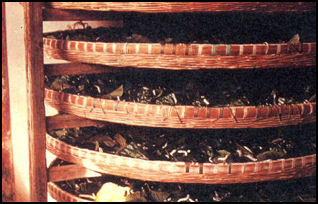

Trays with silkworms

The silkworms are kept in rooms with temperatures between 75̊F and 80̊F. Lights are left on around the clock but are not allowed to shine directly on the caterpillars. Great care is taken to keep the rooms clean and measures are taken to prevent the caterpillars from being exposed to drafts, smoke, odors and noise. Women who raise silkworms in Hangzhou can not smoke, wear make-up or eat garlic, and they must wear clean sandals.

The quality of silk is often determined by the quality of care the silkworms receive. According to ancient Chinese guidelines that are still followed today: "First of all, the bark of a dog, crow of a cock, even a fowl's smell can upset freshly hatched worms. Second, larvae should rest on dry mattresses; and they must sleep, eat, and work in harmony."

"Third, A worm out of sync with the rhythm and transformation of the majority is buried or fed to fish to avoid any variation in the silk. Forth, drowsy newly hatched worms are tickled with a chicken feather to prod development. And finally, the attendant, called silkworm mother, should have no bad smells, should wear clean simple clothes so as not to stir the air, and should not eat chicory (or even touch it)."

Workers bring in huge supplies of mulberry leaves for the silkworms to eat and clean the trays where they live. After they hatch 20 kilograms of silkworms eat about three kilograms of mulberry leaves a day. As they grow they eat more and more. After a month the grubs have grown into larvae that consumer 300 kilograms of mulberry leaves a day. Not long after that the silkworms stop eating and spend about a week making their silk cocoons. The original 20 kilograms of grubs produced from 80 to 120 kilograms of silk, which silk producers buy at around $1 or $2 a kilogram. Some worms are allowed to hatch into moths. Their eggs are collected

Silkworm Cocoons

Silkworms are about three to four inches long when they raise their heads, indicating they ready to begin spinning their cocoons. At this stage they are transferred to trays containing piles of straw on which the caterpillars attach themselves to spin their cocoons.

Once anchored in place the caterpillars move their head in a figure eight position weaving the cocoon around their bodies. Viscous liquid silk is produced by a pair of 15-inch-long glands inside the caterpillars body and ejected through a small hole at a rate of about a foot a minute. When it comes into contact with air it hardens into silk. The caterpillar surround itself completely with a cocoon made of a single continuous filament over a mile long.

After the silk is harvested in China the cocoons are carried in table-size baskets to government purchasing stations. The commune is paid, depending on quality and weight, about three dollars a kilogram (2.2 pounds) for the crop. Some cocoons are set aside to allow the caterpillars to metamorphose into moths for egg production but most are made into silk cloth.

Two or three thousand cocoons yield a pound of silk cloth. It takes 110 cocoons to make a tie, 630 for a blouse, 900 for a shirt, 1,700 for dress and 3000 for a heavy silk kimono.

Silk Production

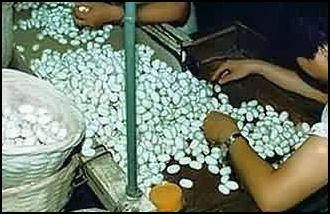

Sorting silk cocoons

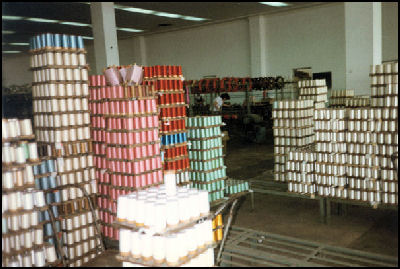

Silk production is largely automated and done in factories but the raising of silk worms to make silk is still very a “cottage industry” done primarily at people’s homes. In some cases government provides anyone who is willing to raise silkworms with 20 kilograms of very small silkworm grubs, which are placed in special boxes in special rooms and fed mulberry leaves gathered from trees near the homes of the farmers raising them.

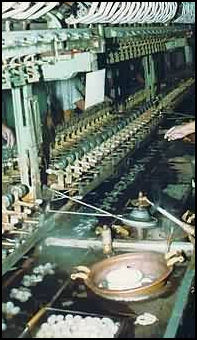

A typical three- to four-centimeter-long cocoon produces a 1- to 1.5-kilometer-long filament. Raw silk needs to be cleaned and twisted into heavier yarns before it is ready for cloth making. This process is called throwing. It is highly mechanized and is similar to spinning cotton. An average factory can produce about six tons of raw silk a month.

The production of silk in a processing mill usually begins when the silk cocoons are placed in a hot-air chambers to kill the caterpillar pupa and dry out the cocoons in such a way that the unbroken silk threads remains undamaged. If they silkworms were allowed to live they would damage the silk threads when they broke out of the cocoon. The cocoons are soaked in hot water to soften them up and get rid of the natural glues. Silkworm cocoon are sometimes yellow and pink; these colors are boiled out during processing. Women often work all day with the hot cloudy water, which is too hot for most of us to touch.

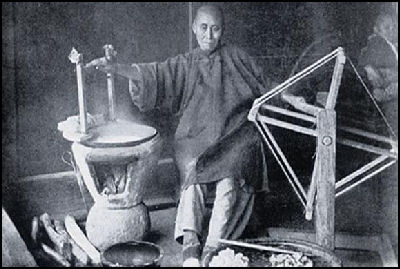

To make silk yarn, the nearly invisible strands from five to eight cocoons plucked from the hot water and plied together and placed into the eye of a reeling machine, which pulls the thread from the cocoons, twists them together into a single yarn that is 800 to 1,200 meters long and is wound on spools. Natural glues left on the strands bind the yarn together. At factories in China, women stand all day in front of reeling machines. If a cocoon stops bobbing, the person operating the reeling machines knows a strand has broken or run out and the end of another cocoon is unraveled and put in its place.

During a second reeling, the silk is measured into specific lengths. The silk yarn is then graded for shipment. The process the silk goes through afterwards often depends on the quality of the silk. Weighted silk is colored with dye and dipped in a solution of metallic salts that add weigh and give it a sheen. Spun silk is made from the floss and other wasted filaments of the silk process. These fibers are carded and spun into yarn using methods similar to those used to make wool.

Wild silk comes most from two kinds of moths: the Antherea mylita of India and the Antherea pernyi of China. The strands from the cocoons made these moths are coarser and more difficult to unravel. They are often made into spun silk.

Richard Kurin at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “When large enough, a worm produces a liquid gel through its glands that dries into a threadlike filament, wrapping around the worm and forming a cocoon in the course of three or four days. The amazing feature of the Bombyx mori is that its filament, generally in the range of 300-1,000 yards — and sometimes a mile — long, is very strong and can be unwrapped. To do this, the cocoon is first boiled. This kills the pupae inside and dissolves the gum resin or seracin that holds the cocoon together. Cocoons may then be soaked in warm water and unwound or be dried for storage, sale, and shipment. Several filaments are combined to form a silk thread and wound onto a reel. One ounce of eggs produces worms that require a ton of leaves to eat, and results in about 12 pounds of raw silk. The silk threads may be spun together, often with other yarn, dyed, and woven on looms to make all sorts of products. It takes about 2,000―3,000 cocoons to make a pound of silk needed for a dress; about 150 cocoons are needed for a necktie. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

Silk Production in China

Silk spinning

Richard Kurin at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “The Chinese traditionally incubated the eggs during the spring, timing their hatching as the mulberry trees come to leaf. Sericulture in China traditionally involved taboos and rituals designed for the health and abundance of the silkworms. Typically, silk production was women's work. Currently, some 10 million Chinese are involved in making raw silk, producing an estimated 60,000 tons annually — about half of the world's output. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution]

After the silk is harvested at Dongshan People's Commune in eastern China the cocoons are carried by boat in table-size baskets to government purchasing stations. The commune is paid, depending on quality and weight, about three dollars a kilogram (2.2 pounds) for the crop.

At a factory in Dadong women stand all day in front of reeling machines washing the silk cocoons and loosening the silk thread with hot cloudy water, which is too hot for most of us to touch. Silk workers near Hotan often starch silk on the loom by spitting water on it.

Women who unwind silk cocoons often plop the silkworms in boiling water and munch on them. “They seem to eat off and on all day long since they work rapidly for long hours at a stretch, and the cooked morsels are constantly before them. One gets a pleasant odor of food being cooked, when passing through a reeling factory.”

Silk Production in Uzbekistan

The Fergana Valley was an important link on the Silk Road. Not only that it has been a major center of silk production in its own right for a long time, perhaps as far back as the A.D. 4th century. Today, Uzbekistan produces about 30,000 metric tons of silk cocoons a year. Most of them are produced in the area in and around the Fergana Valley town of Margalin.

Silk production is largely automated and done in Soviet era factories. Even so the raising of silk worms is still a “cottage industry” done primarily at people’s homes. As was true in the Soviet era, the government provides anyone who is willing to raise the silkworms with 20 kilograms of very small silkworm grubs, which are placed in special boxes in special rooms and fed mulberry leaves gathered from trees near the homes of the farmers raising them.

At the start the 20 kilograms of grubs eat about three kilograms of mulberry leaves a day. As they grow they eat more and more. After a month the grubs have grown into larvae that consume 300 kilograms of mulberry leaves a day. Not long after that the silkworms stop eating and spend about a week making their silk cocoons.

The original 20 kilograms of grubs produces from 80 to 120 kilograms of silk, which silk producers buy at around $1 or $2 a kilogram. Some worms are allowed to hatch into moths. Their eggs are collected.

Silk Products

Chinese doctors replace diseased arteries with silk prostheses. In the 1950s, Dr. Feng Youxian read about grafts in vascular surgery in the United States. "We had no synthetics," he said, "What we had was silk." The material for his first operation was clipped from his shirt and sewn into a tube by his wife.

After the silk has been removed, the shrimp-size silkworm pupae are delivered to restaurants where they are stir fried in garlic, ginger, pepper, soy sauce and oil. Silkworm pupae are high in protein and said to be good for high blood pressure. When the Chinese have finished sucking out the meat they spit the shells on the table and floor.

Silkworm waste, or frass, is used for fish food and fertilizer, and dead pupae are pressed for oil which is made into soaps and cosmetics. Resting one's head on a pillowcase filled with frass is said to ease the pain of rheumatism and frass tea is supposed to cure a number of ailments.

Weaving and Cloth

Silk cloth Weaving is the interlocking at right angles of two sets of fibers to make cloth or a similar material. Spinning is the process by which fibers are drawn and twisted into string, yarn or thread. These tasks have traditionally been done at home by women with looms and spinning devices. The advantage with working at home is that women could work and care for their children at the same time and do weaving and spinning when they are not doing other chores.

To make yarn the old-fashion way: 1) fibers are cleaned and straightened by carding with a toothed card (a sort of brush with stiff bristles). 2) The fibers are then rolled between two cards to produce a thin fiber-like piece called a sliver. 3) The sliver is placed on a spike called a distaff. 4) A strand of wool is then pulled off and a weight known as whorl is attached to it. 5) The strand is twisted into a thread by spinning it with the thumb and forefinger. Since each thread is made this way, you can how time consuming it must have been to make a piece of cloth before machinery was widely used.

To make cloth the old-fashion way: 1) Threads are placed on a warp-weighted loom. Warps are the downward hanging threads on a loom, and they are set up so that every other thread faces forward and the others are in the back. 2) A weft (horizontal thread) is then taken in between the forward and backward row of warps. 3) Before the weft is threaded through in the other direction, the position of the warps is changed with something called a heddle rod. This simple tool reverses the warps so that the row in the front is now in the rear, and visa versa. In this way the threads are woven in a cross stitch manner that holds them together and creates cloth. The cloth in turn is all kinds of things. Cloth is often sold to clothing manufacturers in rolls. One roll of cloth is about 11 meters in length.

Sometimes natural dies are used. Red is made with madder or kermes (an insect found in kermes oak); yellow with wild chamomile, saffron, vine leaves and the rinds of pomegranates; black from acorns; and blue from plants with indigo. Natural dyes produce richer and more natural colors. The depth of color can be controlled by the type of water — rain, river or spring — used. Plant dyes though are notoriously unpredictable. They are affected by weather conditions, soil and when they are harvested. They have mostly been replaced by chemical dyes.

Silk Industry in Japan

Silk production is largely automated and done in factories but the raising of silk worms to make silk is still very a “cottage industry” done primarily at people’s homes. In some cases government provides anyone who is willing to raise silkworms with 20 kilograms of very small silkworm grubs, which are placed in special boxes in special rooms and fed mulberry leaves gathered from trees near the homes of the farmers raising them.

Gumma Prefecture has traditionally been Japan's principal silk producing region. When the silk industry was at its peak Gumma's 25,000 silk raising houses produced more than 40 percent of Japan's silk. Now there are less than 1,000 silk-raising houses.

Everything in a Japanese silk factories was mechanized even the plucking of mulberry leaves. The work place was as sterile as a silicon chip plant, with humidity, airflow, and temperature are all monitored five times a day. Visitors to silk factory were required to wash in a soupy solution tinged with formaldehyde and and wear a starched scrub suit and a gauze face mask. Looms were driven by computers. [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

In the 1980s, more than a billion caterpillars at a silkworm station in Tokorozawa, Japan crawled and fed on blocks of man-made, mulberry-leaf-soybean-cornstarch concentrate, which looked like "granola bars." Caterpillars that refused to eat were prodded with a feather in the direction of their meal. A Japanese physiologist who helped devise the diet, told National Geographic, "It is much easier to prepare food for a person than a silkworm." Over 50 percent of Japan's silkworms were raised this way. [Source: Hyde]

The Gumma Sericultural Experiment Station has breed silkworms that produce pink, yellow, orange, blue, purple and green silks. To achieve this the silkworms are fed dyes mixed with ground mulberry leaves. The colors they eat don't always match up with the colors they produce. To achieve purple the silkworms are fed food mixed with red and blue dye. Colored silk produced in this way is better than died silk because its is dyed to the core and has a more natural color.

These days silkworm technology is being applied to genetic engineering and biotechnology. The National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture has genetically engineered silkworms with genes that cause fluorescence in jellyfish and coral and manipulated them to produce interferon, a medicine used to treat a number of ailments. Japan is a leader in the race to decode the silkworm genome.

World’s Top Silk Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Raw Silk (2020): 1) China: 2354 tonnes; 2) Vietnam: 668 tonnes; 3) Uzbekistan: 517 tonnes; 4) Italy: 331 tonnes; 5) United Arab Emirates: 99 tonnes; 6) Germany: 98 tonnes; 7) Slovenia: 79 tonnes; 8) Romania: 78 tonnes; 9) India: 21 tonnes; 10) United States: 10 tonnes; 11) Kyrgyzstan: 9 tonnes; 12) Tajikistan: 9 tonnes; 13) Poland: 8 tonnes; 14) Tunisia: 7 tonnes; 15) Bulgaria: 3 tonnes; 16) France: 3 tonnes; 17) Azerbaijan: 2 tonnes; 18) Rwanda: 2 tonnes; 19) Norway: 1 tonne. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

Imperial-era silk worm production World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Raw Silk (2020): 1) China: US$121926,000; 2) Vietnam: US$39763,000; 3) Italy: US$20330,000; 4) Uzbekistan: US$18103,000; 5) Romania: US$5511,000; 6) Germany: US$4953,000; 7) Slovenia: US$4797,000; 8) United Arab Emirates: US$2480,000; 9) Kyrgyzstan: US$341,000; 10) Tajikistan: US$337,000; 11) Poland: US$286,000; 12) Singapore: US$267,000; 13) Tunisia: US$264,000; 14) France: US$165,000; 15) United States: US$158,000; 16) India: US$154,000; 17) Bulgaria: US$121,000; 18) Rwanda: US$62,000; 19) Azerbaijan: US$60,000; 20) Denmark: US$7,000; Myanmar: US$7,000

World’s Top Exporters of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2020): 1) Azerbaijan: 96 tonnes; 2) Turkey: 81 tonnes; 3) United States: 43 tonnes; 4) Tajikistan: 29 tonnes; 5) Kazakhstan: 23 tonnes; 6) Myanmar: 22 tonnes; 7) Brazil: 21 tonnes; 8) Afghanistan: 7 tonnes; 9) Kyrgyzstan: 6 tonnes; 10) Belgium: 5 tonnes; 11) China: 4 tonnes; 12) Canada: 2 tonnes; 13) United Kingdom: 1 tonne

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2020): 1) Azerbaijan: US$823,000; 2) Turkey: US$451,000; 3) Tajikistan: US$168,000; 4) Kazakhstan: US$140,000; 5) Myanmar: US$130,000; 6) Brazil: US$129,000; 7) China: US$106,000; 8) United States: US$47,000; 9) Kyrgyzstan: US$37,000; 10) Belgium: US$32,000; 11) Canada: US$32,000; 12) Afghanistan: US$26,000; 13) France: US$18,000; 14) Norway: US$12,000; 15) United Kingdom: US$9,000; 16) Thailand: US$8,000; 17) Philippines: US$7,000; 18) India: US$4,000; 19) Netherlands: US$3,000; 20) South Africa: US$2,000

World’s Top Silk Importing Countries

World’s Top Importers of Raw Silk (2020): 1) India: 1920 tonnes; 2) Romania: 959 tonnes; 3) Italy: 495 tonnes; 4) Vietnam: 346 tonnes; 5) Iran: 221 tonnes; 6) Japan: 147 tonnes; 7) France: 138 tonnes; 8) Germany: 130 tonnes; 9) South Korea: 112 tonnes; 10) China: 94 tonnes; 11) United Arab Emirates: 85 tonnes; 12) Slovenia: 79 tonnes; 13) Pakistan: 65 tonnes; 14) Bulgaria: 35 tonnes; 15) Bangladesh: 32 tonnes; 16) Peru: 32 tonnes; 17) Poland: 29 tonnes; 18) Bosnia and Herzegovina: 28 tonnes; 19) Iraq: 24 tonnes; 20) Tunisia: 19 tonnes [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Raw Silk (2020): 1) India: US$85080,000; 2) Romania: US$54881,000; 3) Italy: US$31962,000; 4) Vietnam: US$13476,000; 5) France: US$10714,000; 6) Japan: US$8838,000; 7) Iran: US$7303,000; 8) Germany: US$6023,000; 9) South Korea: US$5686,000; 10) Slovenia: US$4772,000; 11) Pakistan: US$1763,000; 12) Bangladesh: US$1657,000; 13) Bulgaria: US$1238,000; 14) Peru: US$1194,000; 15) China: US$1190,000; 16) Bosnia and Herzegovina: US$1125,000; 17) Tunisia: US$1113,000; 18) Poland: US$1067,000; 19) Brazil: US$956,000; 20) Iraq: US$933,000

World’s Top Importers of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2020): 1) Netherlands: 1105 tonnes; 2) China: 252 tonnes; 3) Turkey: 99 tonnes; 4) Slovakia: 26 tonnes; 5) Kazakhstan: 23 tonnes; 6) Pakistan: 7 tonnes; 7) Iran: 6 tonnes; 8) Kyrgyzstan: 6 tonnes; 9) France: 5 tonnes; 10) Japan: 3 tonnes; 11) Poland: 2 tonnes; 12) United Kingdom: 2 tonnes; 13) Gambia: 2 tonnes; 14) Greece: 2 tonnes; 15) Canada: 1 tonne; 16) South Korea: 1 tonne

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Reelable Silkworm Cocoons (2020): 1) China: US$3697,000; 2) Turkey: US$499,000; 3) Netherlands: US$473,000; 4) Vietnam: US$185,000; 5) Kazakhstan: US$132,000; 6) Slovakia: US$97,000; 7) Japan: US$82,000; 8) Iran: US$42,000; 9) France: US$41,000; 10) Kyrgyzstan: US$36,000; 11) Poland: US$35,000; 12) Pakistan: US$29,000; 13) South Korea: US$24,000; 14) Greece: US$22,000; 15) Gabon: US$20,000; 16) Canada: US$18,000; 17) United Kingdom: US$15,000; 18) Philippines: US$5,000; 19) Belgium: US$5,000; 20) Norway: US$5,000

Image Sources: University of Washington; Silk Road Foundation; Beifan.com; Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html; Columbia University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2022