SILK ROAD

8th century Sogdian silk Once traveled by camels and merchants carrying silk, porcelain and spices, the 2000-year-old Silk Road was an important corridor for trade and cultural exchanges between Asia and Europe.The name Silk Road conjures up images of caravans trudging through some of the world's highest mountains and most god forsaken deserts. This was true for parts of the route but only tells part of the story. The Silk Road was not one well-established road, but a complex, constantly-changing network of land and sea routes between China, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Europe that was in operation roughly from the 1st century B.C. to the A.D. 15th century. It fell into disuse in the age of sailing in the 16th century. The term Silk Road was coined in 1870 by German geographer Ferdinand van Richthofen, the uncle of the Red Baron.

In terms of a trade network between East and West, the Silk Road was both an overland and sea route. The main all-land Silk Road route went from Xian in eastern China via Kashgar in Western China, Samarkand in Central Asia and Baghdad in the Middle East to coastal cities on the Black Sea and the eastern Mediterranean such as Alexandria in Egypt, Aleppo in Syria and Trabzon in present-day eastern Turkey, where connections were available to Europe. The main sea route went from China via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean to Basra on the Persian Gulf or Suez on the Red Sea, where the goods were then carried overland across Persia and Syria or through Egypt to ports serviced by European merchants such as Alexandria.

Travelers on the overland route could feed their animals off the land and find food and drink along the way. In the early era of the Silk Road, goods were often traded trough barter, only later was money used. Silk Road routes were often disrupted and always changing due the presence of bandits, political alliances, passes closed by snow, droughts, storms, seasonal changes, wars, plagues, horsemen raids, and natural disasters. Many Silk Road towns and caravanserais were located within fortresses for protection from bandits and marauding horsemen. Many also had security forces.

Good Websites and Sources on the Silk Road: Silk Road Seattle washington.edu/silkroad ; Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Silk Road Atlas depts.washington.edu ; Old World Trade Routes ciolek.com; Yo Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project silkroadproject.org ; Marco Polo: Wikipedia Marco Polo Wikipedia ; Works by Marco Polo gutenberg.org ; Marco Polo and his Travels silk-road.com ; Zheng He and Early Chinese Exploration : Wikipedia Chinese Exploration Wikipedia ; Le Monde Diplomatique mondediplo.com ; Zheng He Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Gavin Menzies’s 1421 1421.tv ; First Europeans in Asia Wikipedia ; Matteo Ricci faculty.fairfield.edu Television show: Silk Road 2005, a 10-episode production by China's CCTV and Japan's NHK, with music by Yo Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble. The original series was shown in 1980s.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD CITIES factsanddetails.com; MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; DHOWS: THE CAMELS OF THE MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; MARITIME-SILK-ROAD-ERA SHIPS, EXPORT PORCELAINS AND SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.- A.D. 220) factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618 - 907) factsanddetails.com; MONGOLS AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD, BYZANTIUM AND VENICE factsanddetails.com; END OF THE SILK ROAD AND RISE OF THE EUROPEAN SILK INDUSTRY AND SILK ROAD TOURISM factsanddetails.com; CARAVANS AND TRANSPORTATION ALONG THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD AND BACTRIAN CAMELS AS CARAVAN ANIMALS factsanddetails.com; CAMEL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan, Laurence Kennedy, et al. Amazon.com; “The Silk Road: A New History” by Valerie Hansen Amazon.com; “Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present” by Christopher I. Beckwith Amazon.com; “Life Along the Silk Road” by Susan Whitfield Amazon.com; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com “The Travels of Marco Polo” by Marco Polo and Ronald Latham Amazon.com

Origin of the Silk Road

Tang-era

Sogdian merchant

The Persian and Indo-Greek, or Bactrian, civilizations of Central Asia were China’s neighbors to the west. Together with China, these empires were among the world’s most advanced civilizations in the centuries that coincided with the empires of Rome and Byzantium in the West, from roughly 200 B.C. to A.D. 1000.

After the Alexander the Great’s conquest of western Asia in the 3rd century B.C., the Mediterranean became linked to the Indus Valley in present-day India-Pakistan and the Fergana Valley in Central Asia, opening of the route across the Tarim Basin and the Gansu Corridor to China. This came about around 130 B.C., when the Han Dynasty ambassador Zhang Qian (originally dispatched to help form alliance against the proto-Mongol Xiongnu) traveled widely in Central Asia and established contacts with China there. After the defeat of the Xiongnu, Chinese armies established themselves in Central Asia and opened the strategic Hexi corridor in western China, facilitating trade between the Chinese capital Changan and eventually the rest of East Asia.

The Chinese Emperor Wu di (141-87 B.C.) became interested in developing commercial relationships with the sophisticated urban and trading centers of Fergana, Bactria and Parthian Empire: According to the Hou Hanshu, a late Han period historical record, after hearing Zhang Qian: Wu di “reasoned thus: Fergana (Dayuan “Great Ionians”) and the possessions of Bactria (Ta-Hsia) and Parthian Empire (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, but with weak armies, and placing great value on the rich produce of China”.

The Chinese were greatly attracted by the tall and powerful horses (named “Heavenly horses”) from the Fergana Valley, which were also sought after and valued for fighting by the nomadic Xiongnu. The Chinese subsequently sent numerous embassies, around ten every year, to these countries and as far as Seleucid Syria(established by the successors of Alexander the Great). The Hou Hanshu reads: “Thus more embassies were dispatched to Anxi [Parthia], Yancai [who later joined the Alans ], Lijian [Syria under the Seleucids], Tiaozhi [Chaldea], and Tianzhu [northwestern India]… As a rule, rather more than ten such missions went forward in the course of a year, and at the least five or six.” The Chinese campaigned in Central Asia on several occasions and there were reports of direct encounters between Han troops and Roman legionaries (probably captured or recruited as mercenaries by the Xiong Nu).

“The “Silk Road” essentially came into being from the 1st century B.C., following these efforts by China to develop trade and political contacts to the West and India. The Han Dynasty Chinese army regularly policed the trade route against bandits and nomadic horsemen such as the Xiongnu and Huns. Han general Ban Chao led an army of 70,000 mounted infantry and light cavalry troops in the A.D. 1st century to secure the trade routes, reaching to the Tarim basin in present-day western China. Ban Chao campaigned across the Pamirs and reached the shores of the Caspian Sea and the borders of Parthia. From there the Han general dispatched the envoy Gan Ying to Rome.

Products of the Silk Road

Valuable commodities carried west on the Silk Road included silk and porcelain from China; pepper, batik, spices, perfumes, glass beads, gems and muslin from India; incense, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg from the East Indies, diamonds from Colcond; nuts, sesame seeds, glass and carpets from Persia; and coral and ivory from Siam. Other goods that made their way west included furs, ceramics, medicinal rhubarb, peaches, pomegranates, and gunpowder. In cold areas, flint and steel were among the most sought after products..

The Chinese were not as interested in goods arriving from the West as Europe was in goods arriving from the East. Even so traders coming from the West brought fine tableware, wool, horses, jade, wine, cucumbers, and walnuts. Ivory, gold, tortoise shells, dugs and slaves and animals such as ostriches and giraffes came from Africa. Frankincense and myrrh were brought from Arabia. Mediterranean colored glass was treasured almost as much in some parts of the East as silk was in the West.

Chinese, Roman and Persian empires in AD 1

According to UNESCO: “Whilst the silk trade was one of the earliest catalysts for the trade routes across Central Asia, it was only one of a wide range of products that was traded between east and west, and which included textiles, spices, grain, vegetables and fruit, animal hides, tools, wood work, metal work, religious objects, art work, precious stones and much more. [Source: UNESCO unesco.org/silkroad ~]

“The maritime trade routes have also been known as the Spice Roads, supplying markets across the world with cinnamon, pepper, ginger, cloves and nutmeg from the Moluccas islands in Indonesia (known as the Spice Islands), as well as a wide range of other goods. Textiles, woodwork, precious stones, metalwork, incense, timber, and saffron were all traded by the merchants travelling these routes, which stretched over 15,000 kilometers, from the west coast of Japan, past the Chinese coast, through South East Asia, and past India to reach the Middle East and so to the Mediterranean.” ~

Silk and the Silk Road

Silk was prized as a trade item and was ideal for overland travel because it was easy to carry, took up little space, held up over time, weighed relatively little but was high in value. By weight silk was worth as much as gold and often used as a form of money and could be given as bribes and as tribute.

The silk carried on the Silk Road came in the form of rolls of raw silk, dyed rolls, cloth, tapestries, embroideries, carpets and clothes. Much of the silk that left China was in the raw form and it was turned into embroidered cloth and art work in cities such as Samarkand in Central Asia, Baghdad in the Middle East and Lhasa in Tibet.

In the Silk Road era, silk was used for book coverings, wall hangings, clothes, purses, slippers and boots. It was decorated with floral patters and images of birds and mythical beasts such as winged lions and dragons with elephantine snouts stitched with gold or silver thread. The origin of objects could be determined by examining figures, weaves and threads.

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Although it was only one of many products traded, silk perhaps best encompasses the history of economic and cultural exchange across Eurasia along the "Silk" Road. The value of silk gave it particular appeal as a political and religious symbol, it was widely accepted as a currency, and it served as a medium for artistic exchange. The complex history of silk is both well documented and in some ways but poorly known. [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

SILK, SILK WORMS, THEIR HISTORY AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Early History of Silk

According to a Chinese legend, silk was discovered in 2460 B.C. by the 14-year-old Chinese Empress Xi Ling Shi who lived in a palace with a garden with many mulberry trees. One day she took a cocoon from one of the trees and accidently dropped it in hot water and found she could unwind the shimmering thread from the pliable cocoon. For hundreds of years after that only the Chinese royal family was allowed to wear silk. Xi Ling Shi is now honored as the goddess of silk.

Richard Kurin, a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian institution, wrote: “Silk cultivation and production is such an extraordinary process that it is easy to see why its invention was legendary and its discovery eluded many who sought its secrets. The original production of silk in China is often attributed to Fo Xi, the emperor who initiated the raising of silkworms and the cultivation of mulberry trees to feed them. Xi Lingshi, the wife of the Yellow Emperor whose reign is dated from 2677 to 2597 B.C.E., is regarded as the legendary Lady of the Silkworms for having developed the method for unraveling the cocoons and reeling the silk filament. Archaeological finds from this period include silk fabric from the southeast Zhejiang province dated to about 3000 B.C.E. and a silk cocoon from the Yellow River valley in northern China dated to about 2500 B.C.E. Yet silk cloth fragments and a cup carved with a silkworm design from the Yangzi Valley in southern China dated to about 4000-5000 B.C.E. suggest that sericulture, the process of making silk, may have an earlier origin than suggested by legend. [Source: “The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures” by Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian institution ]

EARLY HISTORY OF SILK AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

Spices and the Silk Road

cloves Spices were among the most valuable commodities carried on the Silk Road. Without refrigeration food spoiled easily and spices were important for masking the flavor of rancid or spoiled meat. Basil, mint, sage, rosemary and thyme could be grown in family herb gardens in Europe along with medicinal plants. Among the the spices and seasonings that came from the East — mainly affordable to merchants and nobles but not ordinary people — were pepper, cloves, mace and cumin. Ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon and saffron — the most valuable of spices from the East — were worth more than their weight in gold.

Pepper, one of the spices that Columbus was looking for when he landed in the America in 1492, had been coming to Europe along the Silk Road at least since Roman times, when many Roman cookbook recipes called for pepper. In the A.D. first century, the satirist Persius wrote:

The greedy merchants, led by lucre, run

To the parch'd Indies and the rising sun

From thence hot Pepper and rich Drugs they bear,

Bart'ring for Spices their Italian ware...

The Malabar Coast of India and the islands of Indonesia have traditionally been the sources of peppercorns for pepper. During the Middle Ages, one medieval town sold 288 kinds of spices, many of whom had an unknown origin. Cinnamon, people were told, came from an exotic bird and cloves were netted in the Nile by Egyptians. Caravans that carried pepper were heavily armed.

Spices were often carried by sea rather than overland. According to UNESCO: “The maritime trade routes have also been known as the Spice Roads, supplying markets across the world with cinnamon, pepper, ginger, cloves and nutmeg from the Moluccas islands in Indonesia (known as the Spice Islands), as well as a wide range of other goods. Textiles, woodwork, precious stones, metalwork, incense, timber, and saffron were all traded by the merchants travelling these routes, which stretched over 15,000 kilometers, from the west coast of Japan, past the Chinese coast, through South East Asia, and past India to reach the Middle East and so to the Mediterranean.” ~ [Source: UNESCO unesco.org/silkroad ~]

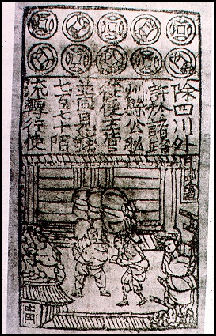

Currencies on the Silk Road

Early paper money According to the Asia Society Museum: “Trade along the Silk Road was conducted using a combination of barter and monetary exchange. Silk, exported in huge quantities from China, was in effect a form of currency (it was also a form of tribute used to buy off the nomads), but due to its perishable nature relatively little has survived. Coins, on the other hand, have been found at widely dispersed sites along the Silk Road, providing evidence of routes, the circulation of currencies, and of cultural exchange. [Source: “Monks and Merchants, curated by Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, November 17, 2001,Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org

== ]

“The two major currencies of the Silk Road, the silver drachm of Sasanian Iran and the gold solidus of the East Roman or Byzantine empire, were struck (stamped) from precious metals. Because their metal was never debased nor their weight reduced, they were ideal for transnational trade. Chinese coins were cast bronze and enjoyed little circulation outside China. ==

“Numerous Sasanian and Byzantine coins have been found in Gansu and Ningxia, particularly in the tombs of officials and merchants of foreign descent. However, it is not certain to what extent they were used as currency, since some are pierced for use as pendants or clothing embellishment and others are not true coins but imitations. ==

The Mongols were the first people to use paper money as their sole form of currency. A piece of paper money used under Kublai Khan was about the size of a sheet of typing paper and had a furry felt-like feel. It was made from the inner bark of mulberry trees and, according to Marco Polo, was "sealed with the seal of the Great Lord."

"Of this money," Marco Polo wrote, "the Khan has such a quantity made that with it he could buy all the treasure in the world. With this currency he orders all payments to be made throughout every province and kingdom and region of his empire. And no one dares refuse it on pain of losing his life...I assure you, that all the peoples and populations who are subject to his rule are perfectly willing to accept these papers in payment, since wherever they go they pay in the same currency, whether for goods or for pearls or precious stones or gold or silver. With these pieces of paper they can buy anything and pay for anything...When these papers have been so long in circulation that they are growing torn and frayed, they are brought to the mint and changed from new and fresh ones at a discount of 3 per cent."

Merchants on the Silk Road

According to the Asia Society Museum: “The most successful traders of the Silk Road were the Sogdians, an Iranian people who inhabited the region of Transoxiana (corresponding to the modern-day republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) in Central Asia. Indeed their language became the lingua franca of the Silk Road. Already by the fourth century, the Sogdians had established numerous communities in China, particularly in Gansu and Ningxia.” According to the “New Tang History,” ca. 9th century, “Men of Sogdiana have gone wherever profit is to be found.” [Source: “Monks and Merchants, curated by Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, November 17, 2001,Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org == ]

“The Sogdians were not only merchants; they were also interpreters, entertainers, horse breeders, craftsmen, and transmitters of ideas. Sogdian scribes were among the first translators of Buddhist texts into Chinese. The majority of Sogdians, however, retained the Zoroastrian beliefs and practices of their homeland and built temples in their communities in China. The Chinese were fascinated by the Sogdians' religious rituals and the uninhibited dancing that took place in these temples. ==

Central Asia Trade Routes

“Cemeteries at Guyuan and Yanchi in Ningxia are two of the few sites directly relating to Sogdians discovered so far, and the most important archaeological evidence of these communities. The occupants were members of the Shi clan whose ancestors had migrated from Kesh, a Sogdian city south of Samarkand. The Guyuan tombs reveal a complex mix of indigenous Chinese and exotic traditions. The tombs themselves were conventionally Chinese in structure, and many of the contents were Chinese. But other objects were either imported or inspired by foreign types or technology. The tombs thus testify both to their owners' adoption of Chinese material culture and to and the links they retained with their ancestral homeland far to the west.” ==

See Separate Article SOGDIANS: MERCHANTS OF THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

Silk Road Communication and the Spread of Ideas

The Silk Road was a conduit for ideas, technology and culture as well as trade. Innovations introduced to Europe from China included playing cards, porcelain, art motifs, styles of furniture, paper money, printing and gunpowder. The Silk Road also facilitated the transmission from one to culture to another of music and dance, language, written scripts, and artistic and craft styles. It is said that in the A.D. 1st century 36 languages were spoken in the markets of the major Central Asian cities.

According to UNESCO: “Perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Silk Roads has been their role in bringing cultures and peoples in contact with each other, and facilitating exchange between them. On a practical level, merchants had to learn the languages and customs of the countries they travelled through, in order to negotiate successfully. Cultural interaction was a vital aspect of material exchange.Moreover, many travellers ventured onto the Silk Roads in order to partake in this process of intellectual and cultural exchange that was taking place in cities along the routes. Knowledge about science, arts and literature, as well as crafts and technologies was shared across the Silk Roads, and in this way, languages, religions and cultures developed and influenced each other. One of the most famous technical advances to have been propagated worldwide by the Silk Roads was the technique of making paper, as well as the development of printing press technology. Similarly, irrigation systems across Central Asia share features that were spread by travellers who not only carried their own cultural knowledge, but also absorbed that of the societies in which they found themselves. [Source: UNESCO unesco.org/silkroad ~]

“Indeed, the man who is often credited with founding the Silk Roads by opening up the first route from China to the West in the 2nd century BC, General Zhang Qian, was on a diplomatic mission rather than a trading expedition. Sent to the West in 139 BC by the Han Emperor Wudi to ensure alliances against the Xiongnu, the hereditary enemies of the Chinese, Zhang Qian was captured and imprisoned by them. Thirteen years later he escaped and made his way back to China. Pleased with the wealth of detail and accuracy of his reports, the emperor sent Zhang Qian on another mission in 119 BC to visit several neighbouring peoples, establishing early routes from China to Central Asia.” ~

CHINA’S GIFTS TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com; IDEAS INTRODUCED FROM CHINA TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com

Silk Road and the Spread of Religion

Beginning in the A.D. 2nd century the Silk Road became a pathway for the flow of Buddhism from India to China and back again. In the 8th century it was the route in which Islam was introduced to Central Asia and western China from the Middle East. Zoroastrianism, Manichaesm, Nestroain Christianity, Judaism, shamanism, Confucianism and Taoism were also spread on the Silk Road.

Buddha from Kizil Caves

According to UNESCO: “Religion and a quest for knowledge were further inspirations to travel along these routes. Buddhist monks from China made pilgrimages to India to bring back sacred texts, and their travel diaries are an extraordinary source of information. The diary of Xuan Zang (whose 25-year journal lasted from 629 to 654 AD) not only has an enormous historical value, but also inspired a comic novel in the sixteenth century, the 'Pilgrimage to the West', which has become one of the great Chinese classics. During the Middle Ages, European monks undertook diplomatic and religious missions to the east, notably Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, sent by Pope Innocent IV on a mission to the Mongols from 1245 to 1247, and William of Rubruck, a Flemish Franciscan monk sent by King Louis IX of France again to the Mongol hordes from 1253 to 1255. Perhaps the most famous was the Venetian explorer, Marco Polo, whose travels lasted for more than 20 years between 1271 and 1292, and whose account of his experiences became extremely popular in Europe after his death. [Source: UNESCO unesco.org/silkroad ~]

“The routes were also fundamental in the dissemination of religions throughout Eurasia. Buddhism is one example of a religion that travelled the Silk Roads, with Buddhist art and shrines being found as far apart as Bamiyan in Afghanistan, Mount Wutai in China, and Borobudur in Indonesia. Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Manicheism spread in the same way, as travellers absorbed the cultures they encountered and then carried them back to their homelands with them. Thus, for example, Hinduism and subsequently Islam were introduced into Indonesia and Malaysia by Silk Road merchants travelling the maritime trade routes from India and Arabia.” ~

SILK ROAD AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; MONGOLS, CHRISTIANITY, NESTORIANS AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

Study of Ancient Toilets Reveals Silk Road Helps Spread Disease

In July 2016, researchers from the University of Cambridge and China's Academy of Social Sciences and Gansu Institute for Cultural Relics and Archaeology announced they hade found evidence of parasitic worms at an ancient Silk Road site in northwestern China. The researchers investigated latrines at the Xuanquanzhi relay station, an archeological site that once served as a rest stop for the Silk Road between 111 B.C. and A.D. 109 AD and found “hygiene sticks” that had bits of cloth stuck to them that were used by people to clean up after using the latrine. Analysis of bits of feces on these sticks revealed eggs from four species of parasitic worms: roundworm, whipworm, tapeworm and Chinese liver fluke. [Source: Piers Mitchell, Affiliated Lecturer in Biological Anthropology, University of Cambridge, The Conversation, July 22, 2016 ]

Piers Mitchell of the University of Cambridge wrote: “Given that the Silk Road was a melting pot of people, it is no wonder that researchers have suggested that it might have been responsible for the spread of diseases such as bubonic plague, anthrax and leprosy between China and Europe. However, no one one has yet found any evidence to show how diseases in eastern China reached Europe. Travellers might have spread these diseases taking a southerly route via India and the Middle East, or a northerly route via Mongolia and Russia. But our team has now found the earliest evidence for the spread of infectious disease organisms along the Silk Road. The results have been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports. ==

“We investigated latrines at the Xuanquanzhi relay station, a fortified stopping point along the Silk Road that was built in 111 BC and used until 109 AD. It is located at Dunhuang, at the eastern end of the Tamrin Basin, an arid region that contacts the fearsome Taklamakan Desert. When the latrines were excavated, the archaeologists found sticks with cloth wrapped around one end. These have been described in ancient Chinese texts of the period as a personal hygiene tool for wiping the anus after going to the toilet. Some of the cloth had a dark solid material still adhered to it after all this time. ==

“We realised that this material was feces when we looked at it with a high-powered optical microscope. We also found the eggs of four species of parasitic intestinal worms in it. This may seem surprising but the eggs of many species of intestinal worms are very tough and may survive thousands of years in the ground. This indicates that some of the people using this latrine 2,000 years ago were infected with parasites. The species included roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), Taenia sp. tapeworm (likely T. solium, T. asiatica or T. solium) and Chinese liver fluke (Clonorchis sinensis). ==

“Roundworm and whipworm are parasites found right across the world in the past and indicate poor personal hygiene, as the worms are spread by the contamination of food and hands by human feces. Taenia sp. tapeworm is spread by eating raw or undercooked meat such as pork and beef, and again has been found across large areas of the world in the past.==

“Meanwhile, Chinese liver fluke – which can cause abdominal pain, diarrhoea, jaundice and liver cancer – is only found in regions of eastern and southern China and Korea, as it has a complex life cycle. It is restricted to areas with wet marshy countryside, as the parasite must pass through the intermediate hosts of a water snail and freshwater fish before it can infect humans. The humans have to eat the fish raw if it is to infect them. In modern times, the closest area to Dunhuang where Chinese liver fluke is found is 1,500km away, and the region where most cases of infection are found is 2,000km away. ==

“Discovering evidence for Chinese liver fluke at a latrine in the arid region of Dunhuang was really exciting. The parasite could not possibly be endemic in that region as there are no marshy areas needed for its life cycle. Instead, it shows that a person who became infected with the liver fluke in eastern or southern China was able to travel the huge distance to this relay station along the Silk Road – at least 1,500km. Our finding suggests that we now know for sure that the Silk Road was responsible for spreading infectious diseases in ancient times. This makes more likely previous proposals that bubonic plague, leprosy and anthrax could also have been spread along it.” ==

Silk Road Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Han dynasty toilet with pigsty

In June 2014, part of the Silk Road was named a UNESCO World Heritage site. CCTV.com reported: “The application was jointly submitted by China,Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. It is the first time China has cooperated with foreign countries for a World Heritage nomination. China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan formally launched the project to apply for adding the initial section of the Silk Road and the routes network of the Tian-shan Corridor onto the World Heritage list.The section is about 5000 kilometers long. It consists of 33 historical sites along the route, including 22 in China, 8 in Kazakhstan and three in Kyrgyzstan. They range from palaces and pagodas in cities to ruins in remote, inaccessible deserts. "The purpose of including the Silk Road onto the World Heritage list is to let people remember it and protect it. The silk road is a road for exchanges. It is a road of friendship. It promoted the cultural development of mankind," said Chinese Academy of Social Sciences archaeologist Liu Qingzhu. It is the first silk road heritage in the world. [Source: CCTV.com, June 21, 2014]

The UNESCO World Heritage Site, formally known as the “Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor”, encompasses the section the Silk Road in China, beginning in present-day Xian, and Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. According to UNESCO: “This property is a 5,000 kilometers section of the extensive Silk Roads network, stretching from Chang’an/Luoyang [present-day Xian], the central capital of China in the Han and Tang dynasties, to the Zhetysu region of Central Asia. It took shape between the 2nd century B.C. and 1st century AD and remained in use until the 16th century, linking multiple civilizations and facilitating far-reaching exchanges of activities in trade, religious beliefs, scientific knowledge, technological innovation, cultural practices and the arts. The thirty-three components included in the routes network include capital cities and palace complexes of various empires and Khan kingdoms, trading settlements, Buddhist cave temples, ancient paths, posthouses, passes, beacon towers, sections of The Great Wall, fortifications, tombs and religious buildings. [Source: UNESCO]

Image Sources: Map, Hofstra University; Merchant, wikipedia; Sogdian Silk, Silk Road Foundation; Silk production, Silk Road Foundation; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021