SILK ROAD AND BACTRIAN CAMELS

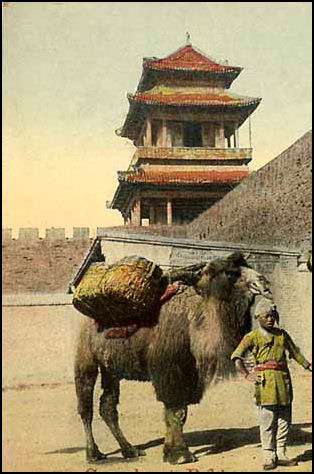

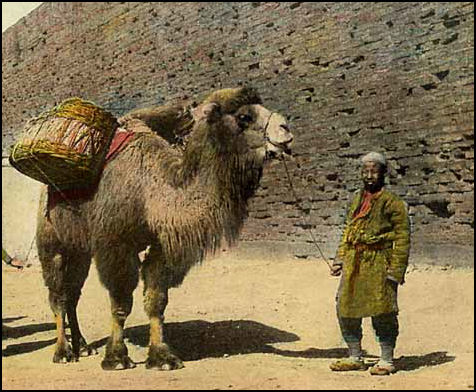

camel outside the gates of old Beijing Bactrian camels were commonly used on the Silk Road to carry goods. They could be employed in high mountains, cold steppes and inhospitable deserts. Camels are one of the most useful animals to humans. Particularly in the desert areas of the Middle East and the steppes of Central Asia, they are used primarily as pack animals but also are useful as mounts and as sources of milk, meat and wool.

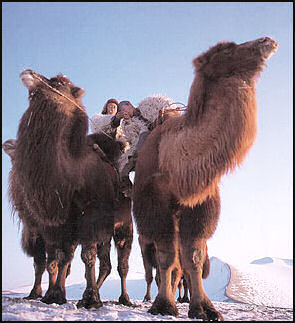

Bactrian camels are hairy double humped animals. Found primarily in Central and East Asia, they are adapted for cold regions and have reddish brown or black hair and have relatively thin, short legs, and heavy bodies. Their calloused feet can handle ice, rocks and snow. They can drink salt water and swim for short distances. Their hair may reach a length of foot in winter. Wild Bactrian camels are still found in China and Mongolia.

Kuo P'u wrote in the A.D. 3rd century: The camel...manifests its merit in dangerous places; it has secret understanding of springs and sources; subtle indeed is its knowledge. Mei Yao-ch'en wrote in the A.D. 11th century:

Crying camels come out of the Western Regions,

Tail to muzzle linked, one after the other.

The posts of Han sqeep them away throught he clouds,

The men of Hu lead them over the snow.

Good Websites and Sources on the Silk Road: Silk Road Seattle washington.edu/silkroad ; Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Silk Road Atlas depts.washington.edu ; Old World Trade Routes ciolek.com;

See Separate Articles: BACTRIAN CAMELS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ; CAMELS: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, HUMPS, WATER, FEEDING factsanddetails.com ; CAMELS AND HUMANS factsanddetails.com ; CARAVANS AND CAMELS factsanddetails.com; CARAVANS AND TRANSPORTATION ALONG THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD: PRODUCTS, TRADE, MONEY AND SOGDIAN MERCHANTS factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan, Laurence Kennedy, et al. Amazon.com; “The Silk Road: A New History” by Valerie Hansen Amazon.com; “Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present” by Christopher I. Beckwith Amazon.com; “Life Along the Silk Road” by Susan Whitfield Amazon.com; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Travels of Marco Polo” by Marco Polo and Ronald Latham Amazon.com

Bactrian Camels

Bactrian camels are camels with two humps and two coats of hair. The long, woolly outer coat varies from brown to beige. The animals have a mane and beardlike hair on their throat. Their feet are broad and adapted for walking on sandy terrain and snow. Adults may exceed three meters in length, stand two meters at the top of the hump and weigh more than 700 kilograms. Widely domesticated and capable of carrying 250 kilograms (600 pounds), they are native to Central Asia, where a few wild ones still live, and seem no worse for wear when temperatures drop to -29 degrees C (-20 degrees F). The fact they can endure extreme hot and cold and travel long periods of time without water has made them ideal caravan animals.

Bactrian camel The humps store energy in the form of fat and can reach a height of half a meter (18 inches) and individually hold as much as 100 pounds. A camel can survive for weeks without food by drawing on the fat from the humps for energy. The humps shrink, go flaccid and droop when a camel doesn’t get enough to eat and the humps lose the fat that keeps them erect.

All camels are believed to have evolved from two-humped Bactrian camels indigenous to Central Asia. The one-humped dromedaries of the Middle East are believed to have evolved from them although their origin is still somewhat of a mystery. The Bactrian camel is believed to have been domesticated in Central Asia 5,000 years ago. The Dromedary camel is believed to have been domesticated in Arabia 3,000 years ago.

Bactrian camels move at about five kilometer per hour and produce five kilograms of wool, 600 liters of milk, and 250 kilograms of dung a year. In the winter they sometimes die because they are unable to scrape away snow from the grass and plants they eat. A Bactrian camel lived to be 36 in Britain. One of that age was still living in a Yokohama zoo in Japan in 2011. Females reach sexual maturity at three to four years, males at five to six years.

Bactrian Camels: the Ideal Caravan Animal

Bactrian camels can go a week without water and a month without food. A thirsty camel can drink 100 to 110 liters (26 to 29 gallons) of water in ten minutes. For protections against sandstorms, Bactrian camels have two sets of eyelids and eyelashes. The extra eyelids can wipe sand like windshield wipers. Their nostrils can shrink to a narrow slit to keep out blowing sand. Bactrian camels slobber a lot when they get horny (See Camel wrestling).

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Bactrian or two-humped camel permits” its users “to transport heavy loads through the desert and other inhospitable terrain. The camel is invaluable not only for transporting the folded gers and other household furnishings when the Mongols move to new pastureland, but also to carry goods designed for trade. A camel could endure the heat of the Gobi desert, could drink enormous quantities of water and then continue for days without liquid, required less pasture than other pack animals, and could extract food from the scruffiest shrubs or blades of grass — all ideal qualities for the daunting desert terrain of southern Mongolia. In addition to the camel's importance for transport,” the animal was valued for its wool, milk (which can also be made into cheese), and meat. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “The camel's great virtues include the ability to carry substantial loads — 400-500 pounds — and their well-known capacity for surviving in arid conditions. The secret to the camel's ability to go for days without drinking is in its efficient conservation and processing of fluids (it does not store water in its hump[s], which in fact are largely fat). Camels can maintain their carrying capacity over long distances in dry conditions, eating scrub and thorn bushes. When they drink though, they may consume 25 gallons at a time; so caravan routes do have to include rivers or wells at regular intervals. The use of the camel as the dominant means of transporting goods over much of Inner Asia is in part a matter of economic efficiency — as Richard Bulliet has argued, camels are cost efficient compared to the use of carts requiring the maintenance of roads and the kind of support network that would be required for other transport animals. In some areas though down into modern times, camels continue to be used as draft animals, pulling plows and hitched to carts. *\ [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

Bactrian Camels and People

young wild Bactrian camel Bactrian camels have a shaggy outer coat that yields soft, highly sought-after "camel hair." The hair is usually plucked in the summer when the camels shed. An average camel yield 2½ pounds of hair a year. The hair is brushed and exported and woven into fine camel hair suits and coats. In hot places, Bactrian camels are sheered in the summer.

Describing the milking of a camel, Thomas Allen wrote in National Geographic: "She wrapped a rope around the camel's back legs and tightened the rope by bracing her knee against the camel's rump. She led a nursing camel up to the female and, as soon as the baby camel began nursing, yanked it away. The woman then began milking the camel, squirting the milk into a dirty tin can."

When a Bactrian camel is ridden a saddle is placed between the camel’s humps. The saddle has a large wooden frame and is difficult to make. One saddle can be traded for one camel. Riding a saddled Bactrian camel is surprisingly comfortable. It is much more comfortable than riding a Sahara-style dromedary camel.

Male camels are often castrated. White camels are regarded as auspicious. It is not unusual for mother camels to reject their calves and refuse to give them milk. When this happens in Mongolia sometimes a musician is called in to play music to induce the camel to weep and accept the calf.

The film “The Story of the Weeping Camel” (2004) was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language film in 2005. It is about a group of Mongolian nomads who use a musical ritual to get a mother camel to weep and accept and nurse her rare white calf, which she previously rejected. As the musician plays his cello-like lament the mother camel appears to weep. The film was directed by Byambasuren Davaa, a Mongolian woman film maker, and financed with German money.

There are fewer camels than there used to be. Sometimes they are eaten for meat. Mostly they are not as useful as they once were. Trucks now carry tents, goods and products that used to carried by camels.

Camels and Silk Road Art

Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “Visual representations of” camels “may celebrate them as essential to the functions and status of royalty. Textiles woven by and for the nomads using the wool from their flocks often include images of these animals. The royal art of the Sasanians (3rd-7th century) in Persia includes elegant metal plates, among them ones showing the ruler hunting from camelback. A famous ewer fashioned in the Sogdian regions of Central Asia at the end of the Sasanian period shows a flying camel, the image of which may have inspired a later Chinese report of flying camels being found in the mountains of the Western Regions. *\

Given their importance in the lives of peoples across inner Asia, not surprisingly camels...figure in literature and the visual arts. A Japanese TV crew filming a series on the Silk Road in the 1980s was entertained by camel herders in the Syrian desert singing a love ballad about camels. Camels frequently appear in early Chinese poetry, often in a metaphorical sense. Examples in the visual arts of China are numerous. Beginning in the Han Dynasty, grave goods often include these animals among the mingqi, the sculptural representations of those who were seen as providing for the deceased in the afterlife. The best known of the mingqi are those from the T'ang period, ceramics often decorated in multicolored glaze (sancai). While the figures themselves may be relatively small (the largest ones normally not exceeding between two and three feet in height) the images suggest animals with "attitude"— camels often seem to be vocally challenging the world around them (perhaps here the "crying camels" of the poet quoted above). [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“A recent study of the camel mingqi indicates that in the T'ang period the often detailed representation of their loads may represent not so much the reality of transport along the Silk Road but rather the transport of goods (including food) specific to beliefs of what the deceased would need in the afterlife. Some of these camels transport orchestras of musicians from the Western Regions; other mingqi frequently portray the non-Chinese musicians and dancers who were popular among the T'ang elite...It is significant that the human attendants (grooms, caravaneers) of the animal figures among the mingqi usually are foreigners, not Chinese. Along with the animals, the Chinese imported the expert animal trainers; the caravans invariably were led by bearded westerners wearing conical hats. The use of foreign animal trainers in China during the Yüan (Mongol) period of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries is well documented in the written sources. *\

“Apart from the well-known scuptures, the images of horse and camel in China also include paintings. Narrative scenes in the Buddhist murals of the caves in Western China often represent merchants and travelers in the first instance by virtue of their being accompanied by camel caravans. Among the paintings on paper found in the famous sealed library at Dunhuang are evocatively stylized images of camels (drawn with, to the modern eye, a sense of humor). The Chinese tradition of silk scroll painting includes many images of foreign ambassadors or rulers of China with their horses.’ *\

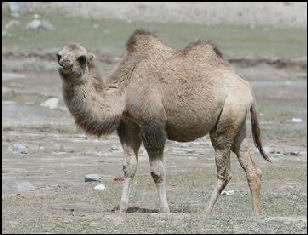

Wild Bactrian Camels

There are fewer than 900 wild Bactrian camels remaining in the wild. They live in three small populations: 1) one on the Mongolian-China border; 2) far western China; and 3) in the Kum Tagh desert. They are threatened by poaching, wolves and illegal mining. Some illegal miners have placed explosives at water holes to blow up camels.

camel outside old Beijing

Ancestors of the domestic camel, wild Bactrian camels are slimmer and less wooly and have smaller conical humps than domesticated Bactrian camels. They stand 172 centimeters at the shoulder. Males weigh 600 kilograms and females weigh 450 kilograms. They eat grasses, leaves and shrubs.

Wild Bactrian camels live on the arid plains, hills and desert in Mongolia and China. They can survive on shrubby plants and no water for 10 days. They follow migratory paths across the desert to oases and feed on tall grasses.

Female Bactrian camels travel in small groups with six to 20 members. Males are often solitary but will unite with a female group in the mating season if strong enough to fend off rivals. During the rutting season males puff out their cheeks, toss their heads, slobber and grind their teeth. Mother Bactrian camels give birth alone. The gestation period is 13 months. Usually one calf, sometimes two, are born. Young can walk almost immediately. After about a month of seclusion mother and young join the group with other females. Young nurse for one to two years.

Image Sources: Silk Road Foundation; Shanghai Museum, CNTO, camel photos.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025