CAMELS: THE IDEAL CARAVAN ANIMAL

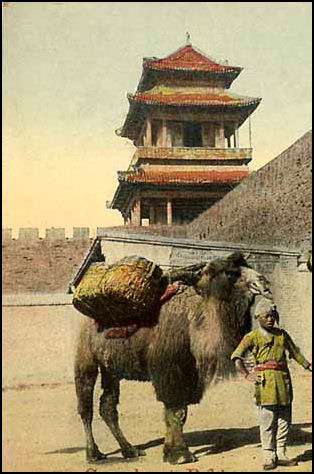

camel outside the gates of old Beijing Daniel C. Waugh of the University of Washington wrote: “The camel's great virtues include the ability to carry substantial loads — 400-500 pounds — and their well-known capacity for surviving in arid conditions. The secret to the camel's ability to go for days without drinking is in its efficient conservation and processing of fluids (it does not store water in its hump[s], which in fact are largely fat). Camels can maintain their carrying capacity over long distances in dry conditions, eating scrub and thorn bushes. When they drink though, they may consume 25 gallons at a time; so caravan routes do have to include rivers or wells at regular intervals. The use of the camel as the dominant means of transporting goods over much of Inner Asia is in part a matter of economic efficiency — as Richard Bulliet has argued, camels are cost efficient compared to the use of carts requiring the maintenance of roads and the kind of support network that would be required for other transport animals. In some areas though down into modern times, camels continue to be used as draft animals, pulling plows and hitched to carts. *\ [Source: Daniel C. Waugh, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

Camels can go a week without water and a month without food. A thirsty camel can drink 100 to 110 liters (26 to 29 gallons) of water in ten minutes. For protections against sandstorms, Camels have two sets of eyelids and eyelashes. The extra eyelids can wipe sand like windshield wipers. Their nostrils can shrink to a narrow slit to keep out blowing sand. Bactrian camels slobber a lot when they get horny (See Camel wrestling).

Camels can carry 250-kilogram loads 50 kilometers a day for days, and go with food or water for more than a week. Camels can carry anything that can be loaded on their backs. In remote areas of the Sahara solar powered refrigerators filled with vaccines have been carried on the backs of camels.

See Separate Articles: CAMELS: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, HUMPS, WATER, FEEDING factsanddetails.com ; CAMELS AND HUMANS factsanddetails.com ; CARAVANS AND TRANSPORTATION ALONG THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BACTRIAN CAMELS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com BACTRIAN CAMELS AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

Modern Caravans

The following descriptions come from articles on modern caravans in the Sahara. The information they yield offers some insights into what it must have been like to travel on a Silk Road caravan or a caravan elsewhere. Most caravans have been replaced by trucks and other forms of transportation. Some still exist in the Himalayas and other mountainous areas where yaks and sheep are used as pack animals.

A typical camel caravan needs at least two camels per person — one to carry the person and one to carry supplies — in addition to the camels carrying whatever goods are being transported. Camels carry things like blankets, food, salt, millet and bales of hay for the camels and camel drivers, in addition to more valuable trading goods. Goods are loaded on cargo racks which are tied on around blankets on the camel's back. [Source: John Hare, National Geographic, December 2002]

In the old days caravans stopped and picked up water and supplies at caravansaries, walled fortresses along major trading routes (See Above). No working caravansaries exist today as the bandits and marauding horsemen that made them necessary no long are a threat. At night caravans stop and make a camp.

Caravan Daily Life

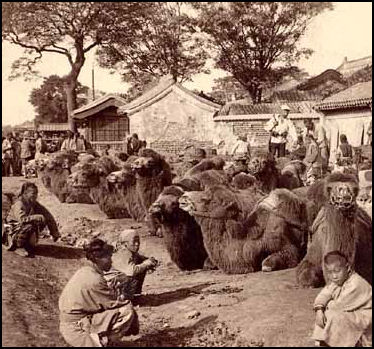

Camel Square The main objective is to keep the caravan going. If you stop it can take hours to sort out the mess. Simply unloading and loading a camel can be a time consuming task. During the day the wind often blows so strongly that caravaneers (camel leaders) have cover their faces and it is impossible to have a conversation with the other people on the caravan.

The caravaneer’s most difficult job is loading the camels, which kick, snarl and make vicious noises when they are being loaded. It takes a lot of time to tie the ropes around the camel and its pack and getting the load balanced is important. Camels that are poorly loaded howl and complain until the job is done right.

When it is very hot, caravans sometimes stop around 11:00pm, the camels are unloaded and hobbled quickly, with the caravaneers dozing and sleeping on mats near small fires. Tying ropes and doing other chores can sometimes be difficult in the morning because it is so cold.

Caravans usually make a fire at night to stay warm in the cold desert. Food includes grain or pasta that is carried by the camels and made into stews or soups with items — such as dates, goat cheese, cabbage, onions and peppers — that are purchased along the way in oasis villages. Leftovers from dinner are eaten for breakfast. Dates are munched for lunch and snacks while the caravan is moving.

Caravan Navigation

Caravans are led by guides who are as skilled in talking and negotiating higher fees as they are in navigating. There are largely self taught or instructed by relatives or other caravan guides and insist they known every dune. Some guides are very good. Some suck and get lost.

Skilled guides generally don't use maps or even compasses. They look upon global position devices with disgust. Instead they rely primarily on their knowledge of the desert, landmarks, wind directions, sun positions and the stars.

Sometimes guides are aiming to reach something as small as difficult-to-find knee-high well. Winds are a big help because they blow relatively consistently based on the time of year and the time of day. Ripples in the sand are regularly checked and a course is plotted by taking the appropriate angle across the ripples.

Caravans sometimes go at night following the North Star, early-evening stars knows as “La Ouaza, or the Intermediaries," which point south, or some other stellar landmark. Guides generally only know a few constellations but claim they can see stars during the day. The problem with traveling at night is that sometimes landmarks seen in the day are missed, and it can also be very cold. Today some people use global positioning devices satellite phones and smart phone apps.

Caravan Traditions

Describing the beginning of a caravan, Thomas Abercrombie wrote in National Geographic, "The “madouga”, or caravan boss, raises his staff, jerks the rope halter of the lead camel, and, to shouts and the clanging of pans and bowls, the half-mile-long train grudgingly lurches forward."

Describing a camel journey in southern Arabia in 1946, Wilfred Thesiger wrote: "We left Shisur...in the chill of dawn; the sun was resting on the desert's rim, a red ball without heat. We walked as usual till it grew warm, the camels striding in front of us, a moving mass of legs and necks. Then one by one, as the inclination took us, we climbed up their shoulders and settled in our seats for the long hours which lay ahead...The Arabs sang, 'the full throated roaring of the tribes'; the shuffling camels quickened their pace, thrusting forward across level ground." [Source: Eyewitness to History, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

Many caravans starting the reciting of the end of the first chapter of the Koran: "Guide us on the straight path, the path of those you have blessed...not those who have gone astray."

Camels as Caravan Animals

Until the invention of airplanes and motor vehicles camels were the only means of crossing the vast deserts of Africa and Asia. Ironically camels can not cross barren deserts without the help of men. They need men to load grass for them to eat in places with no food and they need them to bring water up with buckets from wells.

Camels were known as the "ships of the desert" because they we used primarily in desert areas were no ships could be used. The Koran reads: "on them, as well as in ships, ye ride." Sea travel was much more efficient for long journeys than caravans. A large merchant sailing ship could carry as much as 6,000 camels.

Camels are the preferred caravan animal in dry climates. For some one-way caravans camels are bought at the beginning and sold at the end.

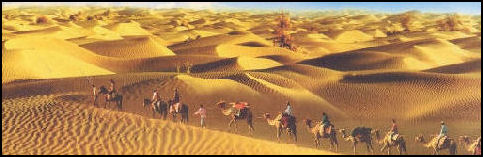

Great effort is made to keep a caravan moving. If it stops it can take great effort to get it going again. Camels on sand dunes find it easier to wind along the ridge tops than go up and down over the dunes.

Camel ticks bite and crawl on the caraveneers.

Camels on a Caravan

Caravans move at about the speed of a walking man. They typically move 2 or 3 miles an hour for nine hours a day from dawn until mid afternoon. Moving at that rate they can cover 1,000 miles in five to eight weeks. Describing a camel on a sand dune, John Hare wrote in National Geographic: “Although the camels sank hock deep in the loose, powdery sand, they struggled on, snaking around, up and over the dunes, grunting when the uphill going was difficult and surging forward on the downhill slopes.”

In the desert and on caravans camels are usually tethered head to tail in a line. Otherwise they tend to become disorderly and head any direction they want. They have to be kept going at the same pace. If not their tethers might break and then there would be a big mess. If they sense water or danger ahead they tend to close formation. Caravan camels are seldom ridden, they are used primarily as pack animals.

At oases the camels can eat palm fronds. Around wells they can feed on tamarisk and acacia trees. In barren areas the can feed on rough grasses and shrubs. Their riders can win their camel’s hearts by sharing some of their dates with them.

Along the caravan route where there is no vegetation camels are fed fed grass carried by the caravan, which the caraveeners sometimes sleep on at night.. Calculating how much grass to carry is important. If you carry to much the camels are unnecessarily burdened. If you don’t bring enough they go hungry. Although camels can go a long time without drinking if they work hard they need food to keep them going. When they haven’t eaten and their stomachs are empty their breath gives off a horrible smell.

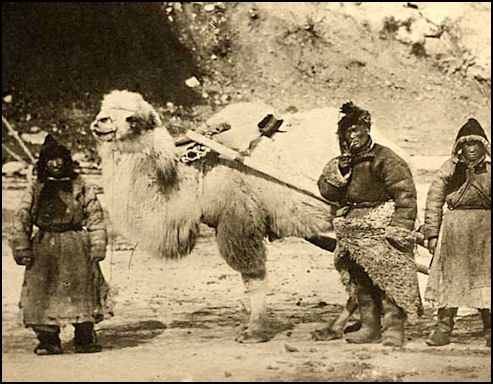

Camel in Mongolia in the early 20th century

Camel Health on a Caravan

If camels start to stumble it a sign that are dangerously sick or exhausted. In some places if a camel becomes sick or exhausted it is bled. If their feet are swollen or cracked sometimes boots are made for them from sheepskin or inner tube rubber. Caravaneers often rise before dawn and cauterize wounds on the camels caused by chaffing from the cargo racks.

If a camel can no longer go on it is abandoned. You can’t risk the other animals or the people. About making such a decision, caravan leader John Hare wrote in National Geographic: “At about 4 p.m. I am forced to abandon the exhausted camel which is being dragged along by its rope at the tail end of the other camels in the caravan. I hate doing it, but I know now there is no alternative. So we release the poor creature that has served us so well, to an inevitable end.”

Many desert tribes don’t like to kill animals by shoting them or slitting their throats so they simply let them go. Some caravan routes are lined with the bones of thousands of camels.

If a calf is born in the middle of a long journey, the caravan can not stop while it gains enough strength to walk for a long distance. The calf is placed in a hammock and tied onto a large camel, who is also carrying a large load, with the mother trailing behind. The calf is not placed with her mother because if she can't see her offspring she goes into a panic and starts heading in the direction of the place she last saw her calf.

End of Caravans

Large long-distance caravans had mostly disappeared by the 19th century but regional ones are still in use in harsh regions where other means of transportation are scarce.

Most caravans have been replaced by diesel trucks, jeeps and cargo planes. But in soft sand that causes vehicles to bog down nothing beats a camel. Speaking in defense of camels, one caravan leader told National Geographic, "The trucks are expensive to buy and maintain while camels are inexpensive to keep...If you are not rich there is only one answer: camels."

Most of the great Saharan oasis languish as ghost towns, market towns or military outposts. There used be hundreds, if not thousands of guides. Now there are only dozens and many get more business from tourist firms than merchants and traders.

Image Sources: Desert towns and and last caravan, CNTO; 1st caravan, Frank and D. Brownestone, Silk Road Foundation; others, Silk Road Foundation

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2022