MARITIME SILK ROAD

Ocean-going dhow More silk and Silk Road goods are believed to have reached the West via sea routes — often collectively referred to as the Maritime Silk Road — than by overland routes.Much of the trade on the Maritime Silk Road was carried out by Arab, Persian and Indian ships not Chinese ones. The trip was dangerous. Many ships disappeared and no one has any idea where they went down. A few went down in well-known dangerous places like the Gelasa Straight, a funnel-shaped passage between the small Indonesian islands of Bangka and Belitung, where the warm tropical waters are freckled with treacherous ship-sinking shallow reefs and submerged rocks.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “From the ninth to fourteenth centuries, navigation flowed along sea routes in Asia. Ships both large and small plied these routes in great numbers back and forth in the seas off China and even as far as the Indian Ocean, making contact with other civilizations in East and Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Arabian Peninsula. With the discovery of new navigation routes in the late fifteenth century, European ships began to make their way to the East in increasing numbers, expanding the distribution of Chinese porcelains” and other goods “made for foreign trade to Europe and the West from the original areas in Asia and Africa, creating a truly global network for trade and commerce. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

According to UNESCO: “Maritime traders had different challenges to face on their lengthy journeys. The development of sailing technology, and in particular of ship-building knowledge, increased the safety of sea travel throughout the Middle Ages. Ports grew up on coasts along these maritime trading routes, providing vital opportunities for merchants not only to trade and disembark, but also to take on fresh water supplies, with one of the greatest threats to sailors in the Middle Ages being a lack of drinking water. Pirates were another risk faced by all merchant ships along the maritime Silk Roads, as their lucrative cargos made them attractive targets. [Source: UNESCO ~]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ To satisfy growing Chinese demand for special spices, medicinal herbs, and raw materials, Chinese merchants cooperated with Moslem and Indian traders to develop a rich network of trade that reached beyond island southeast Asia to the fringes of the Indian Ocean. Into the ports of eastern China came ginseng, lacquerware, celadon, gold and silver, horses and oxen from Korea and Japan. Into the ports of southern China came hardwoods and other tree products, ivory, rhinoceros horn, brilliant kingfisher feathers, ginger, sulfur and tin from Vietnam and Siam in mainland southeast Asia; cloves, nutmeg, batik fabrics, pearls, tree resins, and bird plumes from Sumatra, Java, and the Moluccas in island southeast Asia. Trade winds across the Indian Ocean brought ships carrying cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, turmeric, and especially pepper from Calicut on the southwestern coast of India, gemstones from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), as well as woolens, carpets, and more precious stones from ports as far away as Hormuz on the Persian Gulf and Aden on the Red Sea. Agricultural products from north and east Africa also made their way to China, although little was known about those regions. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

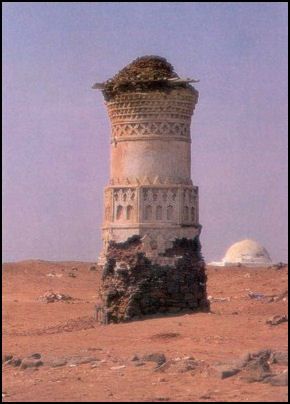

Lighthouse at Mocha “By the beginning of the Ming Dynasty, China had reached a peak of naval technology unsurpassed in the world. While using many technologies of Chinese invention, Chinese shipbuilders also combined technologies they borrowed and adapted from seafarers of the South China seas and the Indian Ocean. For centuries, China was the preeminent maritime power in the region, with advances in navigation, naval architecture, and propulsion. From the ninth century on, the Chinese had taken their magnetic compasses aboard ships to use for navigating (two centuries before Europe). In addition to compasses, Chinese could navigate by the stars when skies were clear, using printed manuals with star charts and compass bearings that had been available since the thirteenth century. Star charts had been produced from at least the eleventh century, reflecting China's concern with heavenly events (unmatched until the Renaissance in Europe).”

Good Websites and Sources on the Silk Road: Silk Road Seattle washington.edu/silkroad ; Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Silk Road Atlas depts.washington.edu ; Old World Trade Routes ciolek.com; Marco Polo: Wikipedia Marco Polo Wikipedia ; Works by Marco Polo gutenberg.org ; Marco Polo and his Travels silk-road.com ; Zheng He and Early Chinese Exploration : Wikipedia Chinese Exploration Wikipedia ; Le Monde Diplomatique mondediplo.com ; Zheng He Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Gavin Menzies’s 1421 1421.tv ; First Europeans in Asia Wikipedia ; Matteo Ricci faculty.fairfield.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD: PRODUCTS, TRADE, MONEY AND SOGDIAN MERCHANTS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD ROUTES AND CITIES factsanddetails.com; DHOWS: THE CAMELS OF THE MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; MARITIME-SILK-ROAD-ERA SHIPS, EXPORT PORCELAINS AND SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan, Laurence Kennedy, et al. Amazon.com; “The Silk Road: A New History” by Valerie Hansen Amazon.com; “Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present” by Christopher I. Beckwith Amazon.com; “Life Along the Silk Road” by Susan Whitfield Amazon.com; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Travels of Marco Polo” by Marco Polo and Ronald Latham Amazon.com

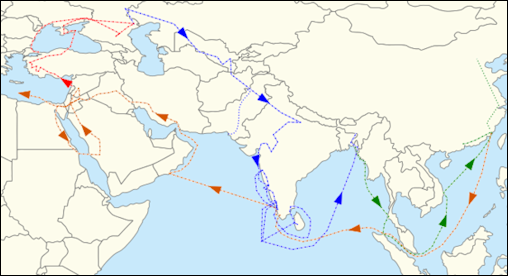

Silk Road Sea Routes

More silk and Silk Road goods are believed to have reached the West via sea routes than by overland routes. The main Silk Road sea routes were between Indian ports like Barbaricon, Barygaza and Muziris and Middle Eastern ports such as Muscat, Sur, Kane and Aden on the Arabian Sea and Muza and Berenike on the Red Sea. From the Middle East goods were transported overland to the Mediterranean Sea and then Europe. From India goods flowed to anf from Southeast Asia, the East Indies and China.

Some maritime sea routes between China. India and the Middle East

Small boats hugged the shore. Large boats sailed the seasonal monsoon winds, which carried boats eastward to India in July, August and September and westward from India to the Middle East in December, January and February. The largest teak-hull ships that plied these routes may have been 180 feet long and capable of carrying cargos of 1,000 tons.

One of the greatest ancient Middle East ports was Bernelike on the Red Sea. In the 1990s archaeologists discovered this ancient city under the sands about 600 miles south of modern-day Suez, near the border of Egypt and Sudan. They found evidence of trade with Thailand and Java, and inscriptions in 11 languages including Greek, Hebrew Coptic and Sanskrit. It was surmised that the ships and crews mostly came from India based on the presence of lots teak, a wood native to India and Southeast Asia.

Berenlike was founded in the 3rd century B.C., rose in importance in the 1st century B.C. and was at its peak in the A.D. 1st century. It was abandoned in the 3rd and 4th centuries and was reborn in the 5th century and thrived until it silted over in the 6th century. It was located far south of the Mediterranean because of unfavorable winds in the Red Sea.

Advantages of Silk Road Sea Routes

Around the A.D. 7th century, during the Tang Dynasty, 500 years before Marco Polo arrived in China, Silk Road land routes fell into decline as sea routes opened up between China and the Middle East. An extensive trade network between China, Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East was established by Arab traders. Chinese coastal cities blossomed. Guangzhou in China had 200,000 foreign residents, including Arabs, Persians, Indians, Africans and Turks.

It is not difficult to see why the caravan routes were abandoned. They were treacherous and time consuming. Merchants had to worry about bandits and pay bribes and commissions to middlemen and officials. Those that traversed western China passed through some of the most barren and inhospitable deserts on earth. When the going was easier thieves and bandits were a constant threat.

Sea routes by contrast were faster and easier and there were fewer transactions and officials. A trader who purchased goods in the East could have control over the goods until they reached ports in the West and make greater profits by eliminating middlemen. The biggest risks with sea travel were storms, disease and pirates.

Land routes began opening up again when the sea routes became dangerous as a result of pirates and the Mogols eliminated petty states and local officials by creating a huge unified empire that stretched across Asia and Europe. Marco Polo traveled by both land and sea but reported more trouble when he traveled by sea.

Dhows in a port

Chinese Trade with Asia

June Teufel Dreyer wrote in YaleGlobal: Well before the arrival of the westerners, there had been a gradual shift away from tribute to trade. During the Ming dynasty, commercial transactions existed between the Ryukyus and parts of Southeast Asia. Private trade existed between China and Japan, even during the so-called sakokuperiod of the 17th century when Japan was theoretically closed to foreign commerce. Chinese court records from the late 1400s indicate concern about trade growth. Despite serious consequences, including decapitation, by the 15th century, a trading system had evolved that encompassed Southeast and North Asia. Since the earliest western power, the Portuguese, did not arrive until 1524, this undermines the contention that trade was imposed from the Occident. The presence of a supreme arbiter might be useful in dispute settlement, yet few would cede that role to Beijing. [Source: June Teufel Dreyer, YaleGlobal, from a longer paper to be published by The Journal of Contemporary China, October 20, 2014 /]

“Moreover, the imposition of treaty trade [after the Opium Wars] did not necessarily result in a worsening of the fortunes of states. Research by Hamashita Takeshi shows that, far from being passive victims of avaricious foreign powers, the western arrivals brought new opportunities. Never actually powerless within the system, these states further increased their autonomy. In one case, in 1884, an envoy from Guangdong told the consul of Siam that stopping its tribute embassies to China was not justified under international law, thereby invoking both tribute and trade systems. The consul replied by suggesting negotiations. Both parties saw their states as in a tributary relationship while simultaneously discussing a treaty between equals. The Koreans likewise combined elements of treaty and trade systems to benefit their best interests.

History of the Maritime Silk Road

Chinese envoys had been sailing through the Indian Ocean to India since perhaps the 2nd century B.C., yet it was during the Tang dynasty that a strong Chinese maritime presence could be found in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Somalia in the Horn of Africa. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to UNESCO: “The history of these maritime routes can be traced back thousands of years, to links between the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization. The early Middle Ages saw an expansion of this network, as sailors from the Arabian Peninsula forged new trading routes across the Arabian Sea and into the Indian Ocean. Indeed, maritime trading links were established between Arabia and China from as early as the 8th century AD. [Source: UNESCO ~]

“Technological advances in the science of navigation, in astronomy, and also in the techniques of ship building combined to make long-distance sea travel increasingly practical. Lively coastal cities grew up around the most frequently visited ports along these routes, such as Zanzibar, Alexandria, Muscat, and Goa, and these cities became wealthy centres for the exchange of goods, ideas, languages and beliefs, with large markets and continually changing populations of merchants and sailors.

“In the late 15th century, the Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, navigated round the Cape of Good Hope, thereby connecting European sailors with these South East Asian maritime routes for the first time and initiating direct European involvement in this trade. By the 16th and 17th centuries, these routes and their lucrative trade had become subject of fierce rivalries between the Portuguese, Dutch, and British. The conquest of ports along the maritime routes brought both wealth and security, as they effectively governed the passage of maritime trade and also allowed ruling powers to claim monopolies on these exotic and highly sought-after goods, as well as gathering the substantial taxes levied on merchant vessels.” ~

Ancient Sea Trade with China

The people in the Philippines had been trading with the Chinese over a long period of time long before the Spanish arrived. Phil Greco, a Los-Angeles-based entrepreneur, has salvaged more than 10,000 pieces of Chinese porcelain—some of them 2,000 years old and others from the Song and Ming dynasties— from 16 ship wreck sites off the Philippine islands of Panay, Mindanao and the Calamian Group, and auctioned them off in New York. Many of the pieces are in surprisingly good condition.

Greco has insured his collection of porcelain at $20 million but their value is unknown. He found the sites with the help of local fisherman and harvested the pottery using divers with weights and lines rather than tanks. In many cases the shipwrecks were embedded in coral reefs and required a considerably amount of work to extract. Archeologists and the Philippine government accuse Greco of plunder.

Chinese traders from what is now Fujian province began arriving in the Philippines in the 10th century. Natural resources from the jungle interior of the Philippines were traded for goods from China and Southeast Asia.

According to Lonely Planet: “The Chinese became the first foreigners to do business with the islands they called MaI as early as the 2nd century AD, although the first recorded Chinese expedition to the Philippines was in AD 982. Within a few decades, Chinese traders were regular visitors to towns along the coasts of Luzon, Mindoro and Sulu, and by around AD 1100 travellers from India, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Siam (Thailand) and Japan were also including the islands on their trade runs. Gold was by then big business in Butuan (on the northern coast of Mindanao), Chinese settlements had sprung up in Manila and on Jolo, and Japanese merchants were buying shop space in Manila and North Luzon. [Source: Lonely Planet =]

“For several centuries this peaceful trade arrangement thrived. Despite the island's well-known riches, the inhabitants were never directly threatened by their powerful Asian trading partners. The key, particularly in the case of China, was diplomacy. Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the tribal leaders of the Philippines would make regular visits to Peking (Beijing) to honour the Chinese emperor.” =

Song-era warship

Seaports and Maritime Trade During the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), thousands of foreigners came and lived in numerous Chinese cities for trade and commercial ties with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Bengalis, Sinhalese, Khmers, Chams, Jews and Nestorian Christians of the Near East, and many others. In 748, the Buddhist monk Jian Zhen described Guangzhou as a bustling mercantile center where many large and impressive foreign ships came to dock. He wrote that "many big ships came from Borneo, Persia, Qunglun (Indonesia/Java)...with...spices, pearls, and jade piled up mountain high", as written in the Yue Jue Shu (Lost Records of the State of Yue). In 851 the Arab merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir observed the manufacturing of Chinese porcelain in Guangzhou and admired its transparent quality. He also provided a description of Guangzhou's mosque, its granaries, its local government administration, some of its written records, the treatment of travelers, along with the use of ceramics, rice-wine, and tea. [Source: Wikipedia +]

During the An Lushan Rebellion Arab and Persian pirates burned and looted Guangzhou in 758, and foreigners were massacred at Yangzhou in 760. The Tang government reacted by shutting the port of Canton down for roughly five decades, and foreign vessels docked at Hanoi instead. However, when the port reopened it continued to thrive. In another bloody episode at Guangzhou in 879, the Chinese rebel Huang Chao sacked the city, and purportedly slaughtered thousands of native Chinese, along with foreign Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Muslims in the process. Huang's rebellion was eventually suppressed in 884. [Source: Wikipedia +]

“Vessels from Korean Silla, Balhae and Hizen Province of Japan were all involved in the Yellow Sea trade, which Silla dominated. After Silla and Japan reopened renewed hostilities in the late 7th century, most Japanese maritime merchants chose to set sail from Nagasaki towards the mouth of the Huai River, the Yangzi River, and even as far south as the Hangzhou Bay in order to avoid Korean ships in the Yellow Sea. In order to sail back to Japan in 838, the Japanese embassy to China procured nine ships and sixty Korean sailors from the Korean wards of Chuzhou and Lianshui cities along the Huai River. It is also known that Chinese trade ships traveling to Japan set sail from the various ports along the coasts of Zhejiang and Fujian provinces.

Maritime Silk Road Trade During the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

The Chinese engaged in large-scale production for overseas export by at least the time of the Tang. This was proven by the discovery of the Belitung shipwreck, a silt-preserved shipwrecked Arabian dhow in the Gaspar Strait near Belitung, which had 63,000 pieces of Tang ceramics, silver, and gold (including a Changsha bowl inscribed with a date: "16th day of the seventh month of the second year of the Baoli reign", or 826, roughly confirmed by radiocarbon dating of star anise at the wreck). [Source: Wikipedia +]

See Separate Article: EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Beginning in 785, the Chinese began to call regularly at Sufala on the East African coast in order to cut out Arab middlemen, with various contemporary Chinese sources giving detailed descriptions of trade in Africa. The official and geographer Jia Dan (730–805) wrote of two common sea trade routes in his day: one from the coast of the Bohai Sea towards Korea and another from Guangzhou through Malacca towards the Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka and India, the eastern and northern shores of the Arabian Sea to the Euphrates River. +

In 863 the Chinese author Duan Chengshi (d. 863) provided a detailed description of the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade in a country called Bobali, which historians suggest was Berbera in Somalia. In Fustat (old Cairo), Egypt, the fame of Chinese ceramics there led to an enormous demand for Chinese goods; hence Chinese often traveled there (this continued into later periods such as Fatimid Egypt). From this time period, the Arab merchant Shulama once wrote of his admiration for Chinese seafaring junks, but noted that their draft was too deep for them to enter the Euphrates River, which forced them to ferry passengers and cargo in small boats. Shulama also noted that Chinese ships were often very large, with capacities up to 600–700 passengers. +

Song-era shops and river boats

Maritime Trade During the Song Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Trade between the Song dynasty and its northern neighbors was stimulated by the payments Song made to them. The Song set up supervised markets along the border to encourage this trade. Chinese goods that flowed north in large quantities included tea, silk, copper coins (widely used as a currency outside of China), paper and printed books, porcelain, lacquerware, jewelry, rice and other grains, ginger and other spices. The return flow included some of the silver that had originated with the Song and the horses that Song desperately needed for its armies, but also other animals such as camel and sheep, as well as goods that had traveled across the Silk Road, including fine Indian and Persian cotton cloth, precious gems, incense, and perfumes. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“There was also vigorous sea trade with Korea, Japan, and lands to the south and southwest. From great coastal cities such as Quanzhou boats carrying Chinese goods plied the oceans from Japan to east Africa. (The major port of Quanzhou that dominated trade in the Song dynasty is not to be confused with Guangzhou. Guangzhou, located further south on the Chinese coast, did not become an important port until the Qing dynasty, when it was known to European traders as “Canton.”

“During Song times maritime trade for the first time exceeded overland foreign trade. The Song government sent missions to Southeast Asian countries to encourage their traders to come to China. Chinese ships were seen all throughout the Indian Ocean and began to displace Indian and Arab merchants in the South Seas. Shards of Song Chinese porcelain have been found as far away as eastern Africa.

“Chinese ships were larger than the ships of most of their competitors, such as the Indians or Arabs, and in many ways were technologically quite advanced. In 1225 the superintendent of customs at Quanzhou, named Zhao Rukua (Zhao Rugua or Chao Ju-kua, 1170-1231), wrote an account of the countries with which Chinese merchants traded and the goods they offered for sale. Zhao's book, Zhufan Zhi (commonly translated as "Description of the Barbarians"), includes sketches of major trading cities from Srivijaya (modern Indonesia) to Malabar, Cairo, and Baghdad. Pearls were said to come from the Persian Gulf, ivory from Aden, myrrh from Somalia, pepper from Java and Sumatra, cotton from the various kingdoms of India, and so on.

“Much money could be made from the sea trade, but there were also great risks, so investors usually divided their investment among many ships, and each ship had many investors behind it. In 1973 a Song-era ship was excavated off the south China coast. It had been shipwrecked in 1277. Seventy-eight feet long and 29 feet wide, the ship had twelve bulkheads and still held the evidence of some of the luxury objects that these Song merchants were importing: more than 5,000 pounds of fragrant wood from Southeast Asia, pepper, betel nut, cowries, tortoiseshell, cinnabar, and ambergris from Somalia.”

On the importance of maritime trade, Lynda Noreen Shaffer wrote: “The new importance of the south [of China] also encouraged China to face south toward the Southern Ocean (the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and parts between) for the first time, and Chinese maritime capabilities developed steadily from the twelfth century to the fifteenth.” [Source: Lynda Noreen Shaffer, In “A Concrete Panoply of Intercultural Exchange: Asia in World History,” in Asia in Western and World History, edited by Ainslie T. Embree and Carol Gluck (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), 840]

In February 2003, about 100 kilometers off Cirebon on the north Java coast, local fishermen caught ceramic objects in their dragnets. They were part of wreckage found at a depth of 56 meters in the Java Sea subsequently named the Cirebon cargo. The local Indonesian fisherman alerted divers and treasure hunters. The site was salvaged between April 2004 and October 2005. It took a team of international divers nearly 22,000 trips to recover the jewels and other goods buried with the boat. The first of these wares surfaced in April 2004. Providing evidence of a vigorous export trade was the largest amount of Yue wares or yue yao, found, forming 75 per cent of the cargo. Ten per cent of the 200,000 pieces was intact, including Yue ewers with bulging bellies, bowls, platters and incense burners as well as figurines of birds, deer and unicorns. [Source: Yvonne Tan, Asian Art Newspaper May 2007 /]

See Separate Article: EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Southern Song (1127-1279) Maritime Trade

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the Southern Song period, communication in art and culture with foreign lands occurred not only through exchange among people and goods with the Jin dynasty to the north, but also in the development of trade with areas to the southeast and southwest. Of particular importance was the expansion of foreign trade via sea routes. With the rise of large harbors dealing in foreign trade at Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Lin'an, and Mingzhou (Ningbo, Zhejiang), the area of trade expanded to the South China Sea and west to as far as Persia, the Mediterranean Sea, and East Africa. The development of Chan (Zen) Buddhist painting and calligraphy was also an important link for the spread of Song culture. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The Southern Song was a time of commerce, with paper money in wide circulation as well as gold, silver leaves or ingots being common currencies, whereas its copper coins went beyond the borders and became the key medium of exchange in many surrounding nations. Through the frontier trading posts, the jewelry and porcelain of the Jin State arrived in the Jiangnan and vast quantities of tea, silk, and herbs of the Southern Song shipped north. Jin and Song as a result shared kindred spirit artistically and literarily. Sea routes also took Chinese merchandise far and wide to many other Asian countries; foreign merchants reaching the shores of China in return brought enriching cultural messages. At the same time, the Taiwan Island and its nearby islets saw the coming and going of the Southern Song traders; their footprints are still here today for us to reminisce about a splendid past.” \=/

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: ““Economic activity and the rising demand for goods was a major spur to scientific and technological creativity, and the foremost historian of the history of science in China has maintained that virtually every core invention of Chinese science traces its origins or a significant innovation to the Song period. For example, the rising output of goods in the South created incentives for the development of maritime trade, so that Chinese goods could reach new markets abroad. The old Silk Route was no longer available to the Song, and, in any event, climate changes had made it much less hospitable to caravan travel than had been the case during the Tang. So for the first time in Chinese history, the merchant class turned towards the sea as a potential commercial highway. Responding to this need, craftsmen applied known technology to create the maritime compass, which allowed ships to navigate as far as the Red Sea, to trade with Middle Eastern markets. Shipbuilding became a major industry, and a host of inventions led to the construction of technologically advanced ships, adaptable to both commercial and military uses.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

China, Trade and the Philippines

The Spanish had initially hoped to turn the Philippines into another Spice Island but they soon found that the island’s soil, terrain and climate were not suited for growing spices. Mining opportunities did not present themselves as they did in Latin America. Trade was stubbled upon sort of by accident.

In 1571, the Spaniards rescued some Chinese sailors whose sampans sunk off the Philippines and helped them get back to China. The next year the grateful Chinese returned the favor in the form of a trading vessel filled with gifts of silk, porcelain and other Chinese goods. This ship was sent eastward and arrived in Mexico in 1573, and its cargo ultimately made it to Spain, where people liked what they saw and a demand for Chinese goods was born.

Manila became the center of a major trade network that funneled goods from Southeast Asia, Japan, Indonesia, India and especially China to Europe. Spain developed and maintained a monopoly over the transpacific trade route. The trade became the primary reason for the existence of the Philippines. Development of the archipelago was largely neglected.

The most important source of goods for the Spanish in the Philippines was China. For a while the Spaniards maintained a trading post on China but for the most part they relied on Chinese intermediaries to bring goods to Manila. About 30 or 40 junks, laden with goods arrived in the Philippines from China a year. Over time the Chinese not only dominated trade but also dominated many of the trades, such as shipbuilding, on which trade was based, and outnumbered the Spanish.

The Chinese were very enterprising, sometimes too much for their own good. A Spanish trader named Diego de Bobadilla wrote: “A Spaniard who lost his nose through a certain illness, sent for a Chinaman to make him one wood, in order to hide the deformity. The workman made him so good a nose that the Spaniard in great delight paid him munificently, giving him 20 escudos. The Chinaman, attracted by the ease with which he made that gain, loaded a fine boatload of wooden noses the next year and returned to Manila.”

Indonesia Trade and the Influence of China

Medieval Sumatra was known as the “Land of Gold.” The rulers were reportedly so rich they threw solid gold bar into a pool every night to show their wealth. Sumatra was a source of cloves, camphor, pepper, tortoiseshell, aloe wood, and sandalwood—some of which originated elsewhere. Arab mariners feared Sumatra because it was regarded as a home of cannibals. Sumatra is believed to be the site of Sinbad’s run in with cannibals.

Sumatra was the first region of Indonesia to have contact with the outside world. The Chinese came to Sumatra in the 6th century. Arab traders went there in the 9th century and Marco Polo stopped by in 1292 on his voyage from China to Persia. Initially Arab Muslims and Chinese dominated trade. When the center of power shifted to the port towns during the 16th century Indian and Malay Muslims dominated trade.

Traders from India, Arabia and Persia purchased Indonesian goods such as spices and Chinese goods. Early sultanates were called “harbor principalities.” Some became rich from controlling the trade of certain products or serving as way stations on trade routes.

The Minangkabau, Acehnese and Batak— coastal people in Sumatra— dominated trade on the west coast of Sumatra. The Malays dominated trade in the Malacca Straits on the eastern side of Sumatra. Minangkabau culture was influenced by a series of 5th to 15th century Malay and Javanese kingdoms (the Melayu, Sri Vijaya, Majapahit and Malacca).

After the Mongol incursions in 1293, the early Majapahitan state did not have official relations with China for a generation, but it did adopt Chinese copper and lead coins ("pisis" or "picis") as official currency, which rapidly replaced local gold and silver coinage and played a role in the expansion of both internal and external trade. By the second half of the fourteenth century, Majapahit’s growing appetite for Chinese luxury goods such as silk and ceramics, and China’s demand for such items as pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and aromatic woods, fueled a burgeoning trade.

China also became politically involved in Majapahit’s relations with restless vassal powers (Palembang in 1377) and, before long, even internal disputes (the Paregreg War, 1401–5). At the time of the celebrated state-sponsored voyages of Chinese Grand Eunuch Zheng He between 1405 and 1433, there were large communities of Chinese traders in major trading ports on Java and Sumatra; their leaders, some appointed by the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) court, often married into the local population and came to play key roles in its affairs.

Image Sources: Marion Kaplan, Nabataea.com, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021