XIAN

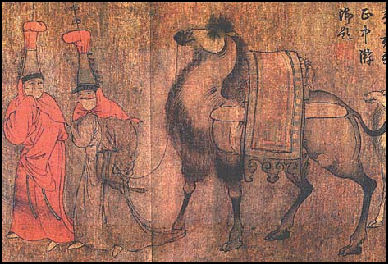

Xian (1,000 kilometers southwest of Beijing, 1,400 kilometers west of Shanghai) served as the eastern gateway to the Silk Road under the Han and Tang Dynasties.According to the Asia Society Museum: “By the late second century B.C., military colonies were established in Gansu to protect the trade routes from nomadic incursions. These colonies became important trading posts on the Silk Road. The main route led from Chang'an (modern Xian) through Lanzhou, Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan to Dunhuang and was protected by a Han extension to the Great Wall. “

Earlier known as Chang'an, Xian was the capital of China from 221 B.C. to A.D. 907. he Western Han Han (206 B.C. - A.D. BC–9) built their capital of Chang'an (meaning "Perpetual Peace") on southern side of the Wei River in an area that roughly corresponds with the central area of present-day Xi'an. During the Eastern Han (A.D. 25–220), Chang'an was also known as Xijing ("Western Capital") as the main capital at Luoyang was to the east.

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “In the seventh and eighth centuries A.D.,” Chang’an “was the center of not only China but the globe — the eastern origin of the trade routes we call the Silk Road and the nexus of a cross-cultural traffic in ideas, technology, art and food that altered the course of history as decisively as the Columbian Exchange eight centuries later. A million people lived within Chang’an’s pounded-earth walls, including travelers and traders from Central, Southeast, South and Northeast Asia and followers of Buddhism, Taoism, Zoroastrianism, Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism. All the while, Shanghai was a mere fishing village, the jittery megapolis of the future not yet a ripple on the face of time. [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

See Separate Article XIAN AND ITS HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD: PRODUCTS, TRADE, MONEY AND SOGDIAN MERCHANTS factsanddetails.com; MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan, Laurence Kennedy, et al. Amazon.com; “The Silk Road: A New History” by Valerie Hansen Amazon.com; “Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present” by Christopher I. Beckwith Amazon.com; “Life Along the Silk Road” by Susan Whitfield Amazon.com; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com “The Travels of Marco Polo” by Marco Polo and Ronald Latham Amazon.com

Silk Road Cities in China: Khotan, Dunhuang and Miran

According to the International Dunhuang Project: “Khotan: The kingdom of Khotan thrived through the first millennium AD. Yotkan, the site of its ancient capital, lies 10 kilometers west of the present-town of Khotan in western China. The founding legends of Khotan are all concerned with Buddhism, and the city's links with India and its thriving Buddhist society is attested by several Chinese monks who visited Khotan en route to India. Khotan had a thriving paper industry, and also produced wool, rugs and fine silk. However, it was most famous for jade, brought down as river boulders, which was in constant demand by the Chinese for its hardness, beauty, and durability. It was probably jade that first made Khotan an important trading stop on the Southern Silk Road. Trade exposed Khotan to diverse influences and the art, manuscripts, terracottas, artefacts and coins found at its capital Yotkan and the town of Dandan-Uiliq, reveal a rich mix of cultures. [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition idp.bl.uk ^/^]

Miran stupa

“Dunhuang has a history of over two thousand years. Lying on the Dang River, which flows south and disappears into the Gobi desert, the town was established as a Chinese military garrison in the 2nd century B.C.. Defensive walls with watchtowers were built to its north. On the junction where the main Silk Road split into northern and southern branches around the Taklamakan desert to its west, Dunhuang grew and prospered. In the 4th century an itinerant monk excavated a meditation cave in a cliff face south-east of the town. Others followed and by the 8th century there were over a thousand cave temples. One cave was used as a library and filled with manuscripts and paintings. It was sealed and hidden in about AD 1000 and its discovery in 1900 revealed an unrivalled source for knowledge of the official and religious life in this ancient Silk Road town.^/^

“Kroraina: Stretching east of Khotan through the Taklamakan and Lop deserts was a string of oases belonging to the kingdom of Kroraina. They flourished in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. By the 7th century many had already met their demise and reverted to the desert, possibly because of climate change. In the extreme aridity of the Taklamakan desert climate, whole landscapes of abandoned towns and farmsteads with their vineyards and orchards still standing were swallowed up by drifting sand dunes. One of the best preserved of these oasis landscapes is the site of Niya. Hundreds of wooden tablets written in the Gandhari language were found here. These everyday letters, administrative and legal records, and tax returns, along with the many items of everyday use discarded as the residents left, open an intimate window onto the realities of daily life along the southern Silk Road. ^/^

“Miran is situated where the Lop Nor desert meets the mountains on the southern Silk Road, between Niya and Dunhuang. Over two thousand years ago, a river irrigated the desert and the settlement developed as an early centre of Buddhism in the kingdom of Kroraina. Many monasteries and stupas were built, decorated with murals and sculptures. After the 4th century, Kroraina declined and Miran was abandoned. It was not until the conquering Tibetian armies arrived in the mid-8th century that it was occupied again. Miran lay on a mountain pass over which the Tibetan armies crossed into Central Asia, and was an ideal location for them to establish a garrison. They built a substantial fort and the community of soldiers and their families restored the old irrigation system. This settlement remained there until after the Tibetan Empire crumbled in the mid-9th century. ^/^

Gaochang: The Tarim Basin lies north-west of Dunhuang across the Gobi Desert. It is the second lowest place on earth with the Heavenly Mountains rising to its north. Meltwater, fertile soil and searing heat produce fine crops here, especially grapes. From the 5th century the capital was at Gaochang, a large walled city. The area fell under the control of several nomadic powers before being conquered by the Chinese in 640. Two centuries later it was taken by the Uighurs, a confederation of Turkic tribes who called the capital Kocho. The plain north of Gaochang, known as Astana, was used as a cemetery from the late 4th century. Almost all the manuscripts from the tombs are in Chinese, but Manichaean texts in Sogdian and Uighur and numerous Buddhist texts in various languages have been found in the ancient city itself.” ^/^

See Separate Articles SILK ROAD SITES IN XINJIANG: TURPAN, KASHGAR AND THE PASSES TO CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com ; TURPAN AREA OF XINJIANG: KAREZ WELLS, GRAPES, ANCIENT SILK ROAD CITIES AND A HOT DEPRESSION factsanddetails.com ; HOTAN (KHOTAN) AND YARKAND AND THE SOUTHERN BRANCH OF THE SILK ROAD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TAKLAMAKAN DESERT AND SOUTHERN SILK ROAD SITES OF KUQA AND KIZIL factsanddetails.com ; SILK ROAD SITES IN GANSU factsanddetails.com; DUNHUANG: SAND DUNES, SILK ROAD SITES, YARDANGS AND MOGAO CAVES factsanddetails.com MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Samarkand

Samarkand in 1929

Samarkand was arguably the grandest city on the Silk Road. It was located at about the halfway point between China and the Mediterranean and situated where the routes from China converged into a single main route through Afghanistan, Iran and the Middle East. Samarkand and other Central Asian, Silk Road cities such as Bukhara and Khiva were centers of art and scholarship, full of poets, astronomers, and master craftsmen.

Samarkand is said to have a history that goes back 6,000 years although 2,500 years is probably a more realistic figure. Alexander the Great captured it in 329 B.C. and reportedly exclaimed, "Everything I have heard about the beauty of Samarkand is true except it is even more beautiful than I could have imagined."

According to the International Dunhuang Project: “North of the modern town of Samarkand lies a grassy plateau called Afrasiab, the name of an evil ruler of the Iranian national epic, the 'Book of Kings'. This marks the site of the first city of Samarkand from its foundation in the 7th or 6th century B.C. to the Mongol invasion in the 13th century AD. Samarkand lies at the heart of the Silk Road in the area once called Sogdiana. The merchants of the Sogdian city-states dominated trade on the Eastern Silk Road from the 3rd and 4th centuries AD onwards. Sogdians lived in market towns along the route all the way into China acting as local agents for their countrymen. The Sogdians were originally Zoroastrians, worshipping at fire altars. Later some became Manichaeans and there were also Buddhist and Nestorian Christian communities. They converted to Islam after the Arab conquests from the late 7th century. [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition idp.bl.uk ^/^]

See Separate Articles SAMARKAND factsanddetails.com SIGHTS AND MUSEUMS IN SAMARKAND factsanddetails.com

Ancient Bukhara

Bukhara is another famed Silk Road city about five hours by car from Samarkand. Its history stretches back for millennia. The origin of its inhabitants goes back to the period of Aryan immigration into the region. Bukhara functioned as one of the main centres of Persian civilization from its early days in the 6th century B.C. Turkic speakers gradually moved in from the A.D. 6th century. During the golden age of the Samanids in the A.D. 9th and 10th centuries, Bukhara became the intellectual center of the Islamic world and therefore, at that time, of the world itself. [Source: Wikipedia +]

According to the Iranian epic poem Shahnameh, the city was founded by King Siavash, son of Shah Kai Kavoos, one of the mythical Iranian kings of the Pishdak (Pishdadian) Dynasty. He said that he wanted to create this town because of its many rivers, its hot lands, and its location on the silk road. As the legend goes, Siavash was accused by his stepmother Sudabeh of seducing her and even attempting to violate her. To test his innocence he underwent trial by fire. After emerging unscathed from amidst the flames, he crossed the Oxus River (now the Amu Darya) into Turan. The king of Samarkand, Afrasiab, wed his daughter, Ferganiza (Persian: Farangis), to Siavash, and further granted him a vassal kingdom in the Bukhara oasis. There he built the Ark or Arg (Persian for 'citadel') and the surrounding city. Some years later, Siavash was accused of plotting to overthrow his father-in-law and become the king of united Iran and Turan. Afrasiab believed this and ordered Siavash's execution in front of Farangis, and buried Siavash's head under the Hay-sellers' Gate. In retaliation, King Kai Kavoos sent Rostam, the legendary super-hero, to attack Turan. Rostam killed Afrasiab, and took Farangis and Siavash's son, Kay Khusrau, back to Persia. +

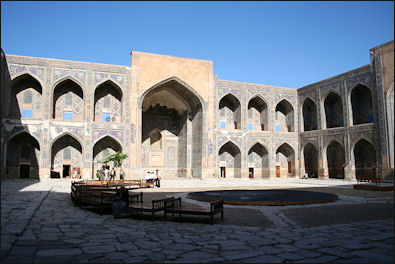

Samarkand madrasa Shir Dar courtyard

Officially Bukhara was founded in 500 B.C. in the area now called the Ark. However, the Bukhara oasis had been inhabited long before. The Russian archaeologist E. E. Kuzmina links the Zaman-Baba culture found in the Bukhara Oasis in the third millennium B.C. to the spread of Indo-Aryans across Central Asia. Since 3000 B.C. an advanced Bronze Age culture called the Sapalli Culture thrived at such sites as Varakhsha, Vardan, Paykend, and Ramitan. In 1500 B.C. a combination of factors—climatic drying, iron technology, and the arrival of Aryan nomads—triggered a population shift to the oasis from outlying areas. Together both the Sapalli and Aryan people lived in villages along the shores of a dense lake and wetland area in the Zeravshan Fan (the Zeravshan (Zarafshan) River had ceased draining to the Oxus). By 1000 B.C. both groups had merged into a distinctive culture. Around 700 B.C. this new culture, called Sogdian, flourished in city-states along the Zeravshan Valley. By this time, the lake had silted up and three small fortified settlements had been built. By 500 B.C. these settlements had grown together and were enclosed by a wall, thus Bukhara was born. +

See Separate Article BUKHARA factsanddetails.com SIGHTS IN BUKHARA factsanddetails.com

Balkh

The storied city of Balkh at the foot of the central highlands in Afghanistan is the legendary home of the great prophet Zoroaster, who lived here centuries before Alexander the Great arrived. And it was in this region that Buddhism was transformed into a vibrant world religion. Frank Harold of Silk Road Seattle wrote: “Balkh was old long before Alexander’s raid, and its history of 2500 years records more than a score of conquerors. The Arabs, impressed by Balkh’s wealth and antiquity, called it Umm-al-belad, the mother of cities. When the Silk Road was the chief artery of commerce between East and West, Balkh was second to none. But then came Ghengis Khan, and wreaked upon it the utter devastation that has made the Mongols’ name a byword for barbarism. Balkh never fully recovered, and eventually faded into a village. [Source: Frank Harold, Silk Road Seattle, University of Washington +]

Why here, on this drab plain between the Hindu Kush mountains and the river Amu Darya (Oxus)? At one level, geography holds the key. Balkh sits on an alluvial fan built up by the Balkab river, well suited to irrigation. The region called Bactria in ancient times was renowned for its grapes, oranges, water lilies and later sugar cane, and an excellent breed of camels too; to this day, some of the world’s most luscious melons come from nearby Kunduz. Most significantly, several natural trade routes intersect at Balkh. From there, caravans could follow the well-watered foot of the mountains westward towards Herat and Iran, or across the Oxus to Samarkand and China. The valley of the Balkab still gives passage to Bamiyan and thence to Kabul; of all the routes across the Hindu Kush, this is the most westerly and the easiest. But geography is at most opportunity, not destiny; and the greatness of Balkh owes even more to those distinctive people who promoted craftsmanship and trade, created cities and wrote poetry all across the Iranian world. On the down side, Balkh was usually rich rather than powerful, and became the envy and the prize of more warlike neighbors. +

“Always a place of importance, Bactria and its capital city figure prominently in the annals of historians and travelers. It first appears on a list of the conquests of Darius, who incorporated it into the Achaemenid empire. Zoroaster taught here, perhaps in the 6th century B.C.E., and the Zoroastrian faith became the state religion of of the Achaemenids and later of the Sassanians. Alexander took Bactria in 329 B.C.E., and made it his base for conquest and amalgamation of the Greek and Iranian civilizations. That vision survived for another two centuries in the small Graeco-Bactrian kingdoms that thrived and quarrelled on both sides of the Hindu Kush; they wrote no history, but minted the most gorgeous silver coins of the ancient world. +

Sufi mystics in modern Balkh

Bactria reappears with its annexation by the Kushans (129 B.C.E.), whose large and powerful empire stretched from Central Asia deep into India. This was a fortunate era, when the lands through which the caravan routes passed were divided among a few stable states which submerged their differences in the interests of trade; and Balkh flourished at the crossroads as a depot and trans-shipment point for the world’s luxuries. “ From the Roman Empire the caravans brought gold and silver vessels and wine; fom Central Asia and China rubies, furs, aromatic gums, drugs, raw silk and embroidered silks; from India spices, cosmetics, ivory and precious gems of infinite variety”. With the merchants came monks preaching the new religion of Buddhism, and Balkh became a center of worship and learning, famous for its temples and monasteries.

“By the time the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (formerly spelled Hsuan Tsang) passed through Balkh (630 C.E.) on his way to the fountainhead of Buddhism in India, the city had become part of the Sassanian empire. The bazaars were still humming with trade, the countryside fertile and the great temples impressed him with their magnificence. But Xuanzang noted laxness among the monks, and the rise of Zoroastrianism. There was strife with the Turki nomads across the Oxus, and the Arab incursions were just fifteen years ahead.”

Merv

Merv (near the village of Bairam Ali, not far from Mary, Turkmenistan) was an important city along the Silk Road and was one of the greatest urban complexes of the medieval world. Founded in 6th century B.C. when a fortified settlement was built here, it was an outpost of the Parthian Empire, one of ancient Rome’s greatest rivals (Roman prisoners were sent here). Merv reached its height in 12th century when it was the capital of the Seljuk Turk empire. At that time it was a major source of watered or Damascus steel and was the equivalent of a medieval industrial complex. Shortly after that it was sacked in brutal fashion by the Mongols.

Merv is actually a site of five wall city that were spread out over an area of 100 square kilometers. The cities were built one after another, each set next to its predecessor. Today these cities are clusters of mounds, mud-brick ruins, ditches and excavation pits scattered among arid plains, where camels graze, here and there. During the summer it can be very hot and there are snakes and scorpions around. It is possible to walk around the vast site, but due to heat it is probably a better idea to hire a taxi and drive around.

Merv was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. According to UNESCO: Ancient Merv is the oldest and most completely preserved of the oasis cities along the Silk Roads in Central Asia. It is located in the territory of Mary velayat of Turkmenistan. It has supported a series of urban centres since the 3rd millennium B.C. and played an important role in the history of the East connected with the unparalleled existence of cultural landscape and exceptional variety of cultures which existed within the Murgab river oasis being in continually interactions and successive development. It reached its apogee during the Muslim epoch and became a capital of the Arabic Caliphate at the beginning of 9th century and as a capital of the Great Seljuks Empire at the 11th-12th centuries.

See Separate Article MARY, MERV AND PLACES IN SOUTHEAST TURKMENISTAN NEAR AFGHANISTAN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Map, Hofstra University; Turpan, CNTO; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021