YARKAND

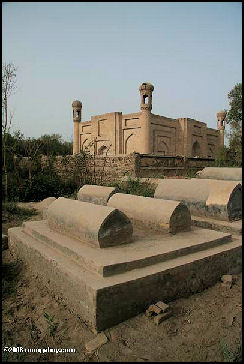

Yarkand tomb

Yarkand (150 kilometers southeast of Kasghar) was a famous Silk Road oasis town. Not very exciting now, it is located on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin and was the seat of an ancient Buddhist kingdom on the southern branch of the Silk Road. The fertile oasis is fed by the Yarkand River which flows north down from the Karakorum mountains and passes through Kunlun Mountains, known historically as Congling mountains ('Onion Mountains' - from the abundance of wild onions found there). The oasis now covers 3,210 square kilometers (1,240 sq mile), but was likely far more extensive before a period of desiccation affected the region from the A.D. 3rd century onwards. [Source: Wikipedia]

Yarkand (Yarkant) has a population of about 370,000 people, the vast majority of them Uyghurs. Sights include Yarkand's old mosque and a Muslim graveyard. Irrigated oasis fields in and around the town produces cotton, wheat, corn, fruits (especially pomegranates, pears and apricots) and walnuts. Yak and sheep graze in the highlands. Mineral deposits include petroleum, natural gas, gold, copper, lead, bauxite, granite and coal. The Xinjiang-Tibet Highway (China National Highway 219), built in 1956 commences in Yecheng-Yarkant and heads south and west, across the Ladakh plateau and into central Tibet.

Yarkand is situated about half way between the important Silk Road towns of Kashgar and Khotan, at the junction of a branch road north to Aksu. It also was the terminus for caravans coming from Kashmir via Ladakh and then over 5,540 meter (18,176 foot) Karakoram Pass — arguably the highest caravn pass in the world — to the oasis of Niya in the Tarim Basin. From Yarkant another important route headed southwest via Tashkurgan Town to the Wakhan corridor — in Afghanistan next to Tajikistan — from where travellers could cross the relatively easy Baroghil Pass and Badakshan. Marco Polo took at least part of this route.

The Yarkand area has been the sight of some anti-Chinese unrest. On a visit there in 2014, Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “We were surprised upon entering the city to see a group of men in helmets, green fatigues and black vests — perhaps riot police — marching by, carrying long, pointy spears. Also unexpectedly, Internet access to smartphones and text-messaging services had been disabled. Down the street, a Han clerk sat in his empty computer shop. Business had dried up since the Internet was shut off, he said. Yarkand, he continued, was unsafe. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 26, 2014]

“We kept walking, into an underground shopping mall. A Uyghur proprietor welcomed us into his shop. He talked of his 3-month-old son, his love for Kobe Bryant, his dreams that his boy would study English. He complained about the restrictions on the Internet, and how few Westerners come to Yarkand these days. Closing up for the night, he rolled down the metal shop door and walked us to a nearby fruit market. "Take my number. If you have any problems, you can call me," he said, pulling out his cellphone. Great, I thought, until he added — unaware of our experience that day — "I've got friends everywhere, even with the police." Web Site: Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

Yarkand’s History

There is very little information on Yarkand's history after the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) apart from a couple of brief references in Tang dynasty (618-907) histories. It was possibly captured by the Muslims soon after they subdued Kashgar in the early 10-11th century. After the Mongol invasions, the area became the main base in the region for Chagatai Khan (died 1241).

Marco Polo described Yarkant in 1273, but said only that this "province" (of Kublai Khan's nephew, Kaidu, d. 1301) was, "five days' journey in extent. The inhabitants follow the law of Mahomet, and there are also some Nestorian Christians. They are subject to the Great Khan's nephew. It is amply stocked with the means of life, especially cotton. From the early 1500s to late 1600s, Yarkand was the capital of a Uyghur kingdom.

The territory of Yārkand is first mentioned in the Book of Han (1st century B.C.) as "Shaju". According to the "Chapter on the Western Regions" in the Hou Hanshu: "Going west from the kingdom of Suoju (Yarkand), and passing through the countries of Puli (Tashkurghan) and Wulei (centred on Sarhad in the Wakhan), you arrive among the Da Yuezhi (Kushans). To the east, it is 10,950 li (4,553 km) from Luoyang.

The Chanyu (Khan) of the Xiongnu took advantage of the chaos caused by Wang Mang (9-24 CE) and invaded the Western Regions. Only Yan, the king of Suoju, who was more powerful than the others, did not consent to being annexed. Previously, during the time of Emperor Yuan (48-33 BCE), he was a hostage prince and grew up in the capital. He admired and loved the Middle Kingdom and extended the rules of Chinese administration to his own country. He ordered all his sons to respectfully serve the Han dynasty generation by generation, and to never turn their backs on it. Yan died in the fifth Tianfeng year (18 CE). He was awarded the posthumous title of 'Faithful and Martial King'. His son, Kang, succeeded him on the throne. At the beginning of Emperor Guangwu's reign (25-57 CE), Kang led the neighbouring kingdoms to resist the Xiongnu. He escorted, and protected, more than a thousand people including the officers, the soldiers, the wife and children of the former Protector General. He sent a letter to Hexi (Chinese territory west of the Yellow River) to inquire about the activities of the Middle Kingdom, and personally expressed his attachment to, and admiration for, the Han dynasty. Yarkand’s early history continues in this vein.

After the Yuanchu period (A.D. 114-120), when the Yuezhi or Kushans placed a hostage prince on the throne of Kashgar: "Suoju [Yarkand] followed by resisting Yutian [Khotan], and put themselves under Shule [Kashgar]. Thus Shule [Kashgar], became powerful and a rival to Qiuci [Kucha] and Yutian [Khotan]." "In the second Yongjian year [A.D. 127] of the reign of Emperor Shun, [Ban] Yong once again attacked and subdued Yanqi [Karashahr]; and then Qiuci [Kucha], Shule [Kashgar], Yutian [Khotan], Suoju [Yarkand], and other kingdoms, seventeen altogether, came to submit. Following this, the Wusun [Ili River Basin and Issyk Kul], and the countries of the Congling [Pamir Mountains], put an end to their disruptions to communications with the west." In 130 CE, Yarkand, along with Ferghana and Kashgar, sent tribute and offerings to the Chinese Emperor.

Hotan

Hotan (500 kilometers southeast of Kashgar, kilometers southeast of Yarkand) was an important stop on the southern branch of the Silk Road. Located Between the Kunlun Shan and the Taklamakan Desert and also called Khotan, it is where Europe-bound caravans recouped after the deserts and China-bound caravans picked up jade. It has an interesting market and production facilities for silk and jade. Many people say it has more of a Silk Road feel than Kashgar.

Hotan is situated in the Tarim Basin about 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) southwest of Urumqi. It lies just north of the Kunlun Mountains. It was part of the chain of oases watered by Kunlun mountain rivers that caravans utilized crossing the Taklamakan Desert. Hindutash and Ilchi passes pass through the Kunlun Mountains to Leh in Ladakh, India. Hotan is dependant on two strong rivers—the Karakash River and the White Jade River — to keep it alive on the southwestern edge of the vast Taklamakan Desert. The White Jade River still provides water and irrigation for the town and oasis.

Hotan is 100 kilometers downstream from the famous "jade mountains," Asia's main source of jade for thousands of years. At the jade buying station in Hotan Uyghur tribesmen deposit their jade boulders onto carpets covered by an inch of dust, the traditional method of displaying the stones. People are often seen by the river look for stones. Khotan also has a famous hand-made silk industry that was reportedly began by a Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) princess who married a local prince and was told if she wanted to wear silk she would have to make her own because there wasn't any in the area.

Modern Hotan is home to about 320,000 people, the vast majority of them being Uyghurs. It is very dusty and everything seems to covered by a film of brown dirt. Despite this local people like to dress in bright reds, yellow and blues. A new 430-kilometer road has been built between Khotan and the town of Alaer. It is being built to transport out oil found in the area. Due to its southerly location in Xinjiang just north of the Kunlun Mountains, during winter it is one of the warmest locations in the region, with average high temperatures remaining above freezing throughout the year. In June 2011, Hotan opened its first passenger-train service to Kashgar, which was established as a special economic zone.

Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Lonely Planet Lonely Planet Getting There: Hotan is accessible by air and bus. The buses from Kashgar take a day or two. The ones from Urumqi can take up to five days.

Early History of Hotan (Khotan)

According to the International Dunhuang Project: “The kingdom of Khotan thrived through the first millennium AD. Yotkan, the site of its ancient capital, lies 10 kilometers west of the present-town of Khotan in western China. The founding legends of Khotan are all concerned with Buddhism, and the city's links with India and its thriving Buddhist society is attested by several Chinese monks who visited Khotan en route to India. Khotan had a thriving paper industry, and also produced wool, rugs and fine silk. However, it was most famous for jade, brought down as river boulders, which was in constant demand by the Chinese for its hardness, beauty, and durability. It was probably jade that first made Khotan an important trading stop on the Southern Silk Road. Trade exposed Khotan to diverse influences and the art, manuscripts, terracottas, artefacts and coins found at its capital Yotkan and the town of Dandan-Uiliq, reveal a rich mix of cultures.” [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition idp.bl.uk]

The oasis of Hotan is strategically located at the junction of the southern (and most ancient) branch of the Silk Road joining China and the West with one of the main routes from ancient India and Tibet to Central Asia and distant China. It provided a convenient meeting place where not only goods, but technologies, philosophies, and religions were transmitted from one culture to another. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tocharians lived in this region over 2000 years ago. Several of the Tarim mummies were found in the area. DNA testing on the mummies found in the Tarim basin showed that they were a mix of Western Europeans and East Asian. An Anthropological study of 56 individuals showed a primarily Caucasoid population.

The main historical sources are to be found in the Chinese histories (particularly detailed during the Han and early Tang dynasties) when China was interested in control of the Western Regions, the accounts of several Chinese pilgrim monks, a few Buddhist histories of Hotan written in Classical Tibetan and a large number of documents in the Iranian Saka language. The ancient Kingdom of Khotan was one of the earliest Buddhist states in the world and a cultural bridge across which Buddhist culture and learning were transmitted from India to China.

The inhabitants of the Kingdom of Khotan, like those of early Kashgar and Yarkant, spoke Saka, one of the Eastern Iranian languages. Khotan's indigenous dynasty (all of whose royal names are Indian in origin) governed a fervently Buddhist city-state boasting some 400 temples in the late 9th/early 10th century—four times the number recorded by Xuanzang around 630. The kingdom was independent but was intermittently under Chinese control during the Han and Tang Dynasty.

The previous border of the British Indian Empire is shown in the two-toned purple and pink band.

After the Tang dynasty, Khotan formed an alliance with the rulers of Dunhuang. Khotan enjoyed close relations with the Buddhist centre at Dunhuang: the Khotanese royal family intermarried with Dunhuang élites. In the 10th century, Khotan began a struggle with the Kara-Khanid Khanate, a Turkic state.[14] The Kara-Khanid ruler, Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, had converted to Islam: Sometime before 1006 Yusuf Qadir Khan of Kashgar besieged and took the city. This marked the end of Buddhist Khotan and beginning of Turkic Muslim Khotan.

When Marco Polo visited Khotan in the 13th century, he noted that the people were all Muslim. He wrote that: Khotan was "a province eight days’ journey in extent, which is subject to the Great Khan. The inhabitants all worship Mahomet. It has cities and towns in plenty, of which the most splendid, and the capital of the province, bears the same name as that of the province…It is amply stocked with the means of life. Cotton grows here in plenty. It has vineyards, estates and orchards in plenty. The people live by trade and industry; they are not at all warlike".

Modern History of Hotan

During the Republican era (1912–49), warlords and local ethnic self-determination movements wrestled over control of Xinjiang. Abdullah Bughra, Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra, and Muhammad Amin Bughra declared themselves Emirs of Khotan during the Kumul Rebellion. Tunganistan was an independent administered region in the southern part of Xinjiang from 1934 to 1937. Beginning with the Islamic rebellion in 1937, Hotan and the rest of the province came under the control of warlord Sheng Shicai. Sheng was later ousted by the Kuomintang. Shortly after the Communists won the civil war in 1949, Hotan was incorporated into the People's Republic of China. [Source: Wikipedia

Following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, ethnic tensions rose in Xinjiang and in Hotan in particular. As a result, the city has seen occasional bouts of violence. In July 2011, 18 people died when rioters in Hotan stormed a police station and a bomb and knife attack occurred on the city's central thoroughfare. In June 2011, authorities in Hotan Prefecture sentenced Uyghur Muslim Hebibullah Ibrahim to ten years imprisonment for selling "illegal religious materials". In June 2012, Tianjin Airlines Flight 7554 was hijacked en route from Hotan to Ürümqi.

In June 2013, two days 35 people were killed in an attack against a police station not far from Hotan. Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times, “ A brief report issued by Tianshan Net, an official news Web site for Xinjiang, said that in Hanairike Township in Hotan, a crowd wielding weapons “assembled in a disturbance, and the public security authorities took emergency action and detained people taking part, rapidly quelling them." The report said that “during the handling of the incident, no members of the public were killed or injured," leaving it unclear whether any police officers or officials were hurt or even killed. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, June 28, 2013 |~|]

“The clashes came just before the fourth anniversary of widespread bloodshed in Urumqi, when at least 197 people were killed on July 5, 2009, after the police broke up a protest by Uyghurs and the confrontation gave way to attacks by rioters on Han people. Yang Shu, a Chinese professor who studies unrest in Xinjiang, said the recent violence reflected Uyghur grievances about social inequalities and dislocation driven by economic modernization, the spreading influence of militant currents of Islam and the deterioration of ethnic relations since 2009.

Sights in the Area Hotan

Hotan has one of the biggest markets in western China and Central Asia, attracting 100,000 shoppers ever day. Merchants sell everything from sides of mutton to threads if saffron. Six miles to the west is the large ruined city of Yoktan (Yutian), an important Buddhist trading center on the Silk Road. Most of what remains are foundations, piles of mud bricks and sand dunes. Sultanim Cemetery was the central Uyghur graveyard and a sacred shrine in Hotan city. Between 2018 and 2019, the cemetery was demolished and made into a parking lot.

Sampul (east of Hotan) contains an extensive series of cemeteries scattered over an area about one kilometers wide and 23 kilometers long. The excavated sites range from about 300 B.C. to A.D. 100. The excavated graves have produced a number of fabrics of felt, wool, silk and cotton and even a fine bit of tapestry, the Sampul tapestry, showing the face of Caucasoid man which was made of threads of 24 shades of colour. The tapestry had been cut up and fashioned into trousers worn by one of the deceased. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dandan-Uyliq (five kilometers west of Hotan) is where some lovely Tang-era Buddhist murals were discovered. The 45-by-30-centimeter masterpieces have been described as the “Mona Lisa” of Buddhist art because of the way he glances off to one side with unusual expression. Dandan-Uyliq is believed to have been a Buddhist center in the 7th and 8th centuries. Traces of more than 20 temples have been found there, Most of the site in unexcavated and off limits to tourists.

Hotan Museum officially opened in May 2020. The culture center converted museum is the first museum in Hotan prefecture. More than 1,300 precious cultural relics are on display, many of which tell the history of the ancient Silk Road. The collection includes cultural relics, ranging from bronze ware, pottery, jade and coins to ancient books and fabric specimens. According to Chinese government propaganda: Among them, the one most appealing to visitors is a piece of brocade with eight Chinese characters that literally read "Five stars rise in the East, benefitting China."” [Source: Xinhua, May 19, 2020]

Hotan and Jade

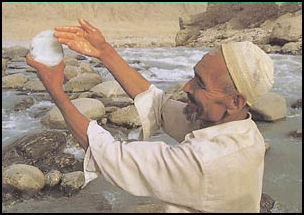

Hotan is 100 kilometers downstream from the famous "jade mountains," Asia's main source of jade for thousands of years. At the jade buying station in Hotan Uyghur tribesmen deposit their jade boulders onto carpets covered by an inch of dust, the traditional method of displaying the stones. People are often seen by the river look for stones. Some of the highest quality jade in China — most notably the whitish mutton fat jade — comes from an area along the banks of the Yulong Kashgar River near Hotan. Two-thousand-year-old historical records refer to a Jade Road from the area.

In imperial times, Hotan jades were sent as tributes to Chinese emperors and carved into exquisite works of art and made into chops used to seal official documents. The price of Hotan nephrite soared in the mid-2000s, quadrupling in value in 2007 alone to 10,000 yuan (US$1,347) a gram for the best-quality stone, or 40 times the value of gold. One piece of Hotan mutton fat jade weighed 11,795 pounds was carved into an image of an ancient emperor leading flood control efforts. It now resides in the Forbidden City. Today Hotan jade accounts for about 10 percent of the annual US$1.2 billion jade trade in China. Much of it is mined by small-time prospectors with sieves who hope for a big strike but get by mostly with relatively small pieces of white, green and brown jade that they can sell for a few cents a day,

Nephrite found in western China has traditionally been collected by "jade pickers" who wander the shores of dry river beds picking up stones washed down from the nearby Jade Mountains during the spring floods. In recent years the Hotan area has become flooded with jade prospectors, so many in fact that some people worry that the area could suffer environmental damage that could last a long time and the resource that have kept the region going for millennia could be used up. Most worrisome is the damage caused by big mining operations. According to some reports 80 percent of Hotan 's jade has been exploited as of 2006 and there is only enough to last for three to five more years.

A ban has been placed on mining along the Yulong Kashgar River but the ban has had little effect and mining has pretty much continued as before because local officials have been bribed by the big miners. As many a's 20,000 people and 2,000 pieces of heavy equipment continue to work the area, leaving behind strip-mine-like gashes as deep as 30 feet.

See Separate Article CHINESE JADE factsanddetails.com

Faxian on the Journey to Khotan

Between A.D. 399 and 414, the Chinese monk Faxian (Fa-Hsien, Fa Hien) undertook a trip via Central Asia to India to study Buddhism, locate sutras and relics and obtain copies of Buddhist books that were unavailable in China at the time. He traveled from Xian in central China to the west overland on the southern Silk Road into Central Asia and described monasteries, monks and pagodas there. He then crossed over Himalayan passes into India and ventured as far south as Sri Lanka before sailing back to China on a route that took him through present-day Indonesia. His entire journey took 15 years.

Chapter II: On to Shen-shen and Thence to Khoten

According to Faxian’s “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms”: “After travelling for seventeen days, a distance we may calculate of about 1500 li, (the pilgrims) reached the kingdom of Shen-shen [Lou-lan, near Lop Nor], a country rugged and hilly, with a thin and barren soil. The clothes of the common people are coarse, and like those worn in our land of Han, some wearing felt and others coarse serge or cloth of hair — this was the only difference seen among them. The king professed (our) Law, and there might be in the country more than four thousand monks, who were all students of the Hinayana [Thereavada]. The common people of this and other kingdoms (in that region), as well as the sramans [monks], all practise the rules of India, only that the latter do so more exactly, and the former more loosely. So (the travellers) found it in all the kingdoms through which they went on their way from this to the west, only that each had its own peculiar barbarous speech. [Source: “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Fa-Hsien (Faxian) of his Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414), Translated James Legge, 1886, gutenberg.org/ /]

“(The monks), however, who had (given up the worldly life) and quitted their families, were all students of Indian books and the Indian language. Here they stayed for about a month, and then proceeded on their journey, fifteen days walking to tho north-west bringing them to the country of Woo-e [near Kucha or Karashahr on the northern edge of the Tarim?]. In this also there were more than four thousand monks, all students of the Hinayana. They were very strict in their rules, so that sramans from the territory of Ts-in [i.e., northern China] were all unprepared for their regulations. Fa-hien, through the management of Foo Kung-sun, overseer, was able to remain (with his company in the monastery where they were received) for more than two months, and here they were rejoined by Pao-yun and his friends. /

“(At the end of that time) the people of Woo-e neglected the duties of propriety and righteousness, and treated the strangers in so niggardly a manner that Che-yen, Hwuy-keen, and Hwuy-wei went back towards Kao-ch'ang [Khocho, near Turfan], hoping to obtain there the means of continuing their journey. Fa-hien and the rest, however, through the liberality of Foo Kung-sun, managed to go straight forward in a south-west direction. They found the country uninhabited as they went along. The difficulties which they encountered in crossing the streams and on their route, and the sufferings which they endured, were unparalleled in human experience, but in the course of a month and five days they succeeded in reaching Yu-teen [Khotan]." /

See Separate Article: FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com ; FAXIAN IN INDIA factsanddetails.com ; FAXIAN’S RETURN TRIP FROM INDIA TO CHINA factsanddetails.com .

Faxian on the Processions of Images, The King's New Monastery in Khotan

According to Faxian’s “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms”: “Yu-teen is a pleasant and prosperous kingdom, with a numerous and flourishing population. The inhabitants all profess our Law, and join together in its religious music for their enjoyment. The monks amount to several myriads, most of whom are students of the Mahyana. They all receive their food from the common store. Throughout the country the houses of the people stand apart like (separate) stars, and each family has a small stupa [stupa] reared in front of its door. The smallest of these may be twenty cubits high, or rather more. They make (in the monasteries) rooms for monks from all quarters, the use of which is given to travelling monks who may arrive, and who are provided with whatever else they require. [Source: “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Fa-Hsien (Faxian) of his Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414), Translated James Legge, 1886, gutenberg.org/ /]

“The lord of the country lodged Fa-Hsien and the others comfortably, and supplied their wants, in a monastery called Gomati, of the mahayana school. Attached to it there are three thousand monks, who are called to their meals by the sound of a bell. When they enter the refectory, their demeanour is marked by a reverent gravity, and they take their seats in regular order, all maintaining a perfect silence. No sound is heard from their alms-bowls and other utensils. When any of these pure men require food, they are not allowed to call out (to the attendants) for it, but only make signs with their hands. /

“Hwuy-king, Tao-ching, and Hwuy-tah set out in advance towards the country of K'eeh-ch'a; but Fa-Hsien and the others, wishing to see the procession of images, remained behind for three months. There are in this country four great monasteries, not counting the smaller ones. Beginning on the first day of the fourth month, they sweep and water the streets inside the city, making a grand display in the lanes and byways. Over the city gate they pitch a large tent, grandly adorned in all possible ways, in which the king and queen, with their ladies brilliantly arrayed, take up their residence (for the time). /

“The monks of the Gomati monastery, being Mahayana students, and held in greatest reverence by the king, took precedence of all the others in the procession. At a distance of three or four li from the city, they made a four-wheeled image car, more than thirty cubits, high, which looked like the great hall (of a monastery) moving along. The seven precious substances [i.e., gold, silver, lapis lazuli, rock crystal, rubies, diamonds or emeralds, and agate] were grandly displayed about it, with silken streamers and canopies harging all around. The (chief) image [presumably Sakyamuni] stood in the middle of the car, with two Bodhisattvas in attendance on it, while devas were made to follow in waiting, all brilliantly carved in gold and silver, and hanging in the air. When (the car) was a hundred paces from the gate, the king put off his crown of state, changed his dress for a fresh suit, and with bare feet, carrying in his hands flowers and incense, and with two rows of attending followers, went out at the gate to meet the image; and, with his head and face (bowed to the ground), he did homage at its feet, and then scattered the flowers and burnt the incense. When the image was entering the gate, the queen and the brilliant ladies with her in the gallery above scattered far and wide all kinds of flowers, which floated about and fell promiscuously to the ground. In this way everything was done to promote the dignity of the occasion. The carriages of the monasteries were all different, and each one had its own day for the procession. (The ceremony) began on the first day of the fourth month, and ended on the fourteenth, after which the king and queen returned to the palace. /

“Seven or eight li to the west of the city there is what is called the King's New monastery, the building of which took eighty years, and extended over three reigns. It may be 250 cubits in height, rich in elegant carving and inlaid work, covered above with gold and silver, and finished throughout with a combination of all the precious substances. Behind the stupa there has been built a Hall of Buddha of the utmost magalficence and beauty, the beams, pillars, venetianed doors, and windows being all overlaid with goldleaf. Besides this, the apartments for the monks are imposingly and elegantly decorated, beyond the power of words to express. Of whatever things of highest value and preciousness the kings in the six countries on the east of the (Ts'ung) range of mountains [probably this means southwestern Xinjiang] are possessed, they contribute the greater portion (to this monastery), using but a small portion of them themselves." /

Xuanzang Journey from Khotan and Niya Home

In A.D. 629, early in the Tang Dynasty period, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan Tsang) left the Chinese dynasty capital for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He traveled west — on foot, on horseback and by camel and elephant — to Central Asia and then south and east to India and returned in A.D. 645 with 700 Buddhist texts from which Chinese deepened their understanding of Buddhism. Xuanzang is remembered as a great scholar for his translations from Sanskrit to Chinese but also for his descriptions of the places he visited — the great Silk Road cities of Kashgar and Samarkand and the great stone Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. His trip inspired the Chinese literary classic “Journey to the West” by Wu Ch'eng-en, a 16th century story about a wandering Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit. It is widely regarded as one of the great novels of Chinese literature. [Book: "Ultimate Journey, Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk Who Crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment" by Richard Bernstein (Alfred A. Knopf); See Separate Article on Xuanzang]

Sally Hovey Wriggins wrote: His next important stop was Khotan, a fortnight's journey on the caravan road. It was the largest oasis on the Southern Silk Road. Khotan also produced rugs, fine felt and silk as well as black and white jade. Everywhere he found evidence of Indian influence. The local tradition was that Khotan had been settled by Indians from Taxila. Xuanzang visited a monastery built to commemorate the introduction of silk culture from China circa 140 CE when the king's wife, a Chinese princess, brought silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds in her headdress to the king. Xuanzang spent 7 or 8 months in Khotan still waiting for some of the lost scriptures. Finding a trader who was going to Chang’an, he sent a letter to the emperor, saying that he was on his way home. In 629 CE he had left China against the emperor's wishes and didn't know how he would be received on his return. But after several months a messenger arrived with the emperor's reply in which he expressed great pleasure at the news of Xuanzang's imminent return. [Source: “Xuanzang on the Silk Road” by Sally Hovey Wriggins mongolianculture.com \~/]

“Soon afterwards, he left Khotan. Xuanzang does not provide much information about places on the southern Silk Road. After leaving Niya he describes the Taklamakan desert as “a desert of drifting sand without water of vegetation, burring hot and the hound of poisonous fiends and imps. There is no road, and travelers in coming and going have only to look for the deserted bones of man and beast as there guide...When these winds rise, then both men and beasts become confused and forgetful. At times sad and plaintive notes are heard and piteous cries so that between the sights and sounds of this desert men get confused and know not whither they go..Hence there are many who perish on the journey." Marco Polo described similar phenomena.

Xuanzang rested from his desert traveling at Dunhuang at the juncture of the northern and southern silk roads and the home of Mogao Caves, a famous Buddhist shrine, library and gallery of Buddhist art. He is said to have deposited his precious manuscripts in the monastic library at the caves. A wall painting in Cave No. 103 illustrates a sutra and may portray Xuanzang on his way back from India with the elephant given to him by King Harsha. \~/

Xuanzang was still officially a fugitive in his homeland, China, because he had left without permission. Xuanzang wrote a letter to the emperor describing what he had learned and as a result, the emperor not only welcomed him back, but appointed him a court advisor. [Source: Asia Society]

Niya Ruins

Niya Ruins (115 kilometers north of modern Niya, 400 kilometers east-northeast of Hotan) is located the southern edge of the Tarim Basin and was a Silk Road oasis. Numerous ancient archaeological artifacts have been uncovered at the site. According to the International Dunhuang Project: “ One of the best preserved of these oasis landscapes is the site of Niya. Hundreds of wooden tablets written in the Gandhari language were found here. These everyday letters, administrative and legal records, and tax returns, along with the many items of everyday use discarded as the residents left, open an intimate window onto the realities of daily life along the southern Silk Road. [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition]

Beginning in ancient times camel caravans carrying goods from China to Central Asia stopped in Niya. An independent oasis state called Jingjue, generally thought to be Niya, is mentioned in a Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) historical document called the Hanshu: “The seat of the king's government is the town of Jingjue, and it is distant by 8,820 li [probably 3,667 km/2,279 miles] from Ch'ang-an. There are 480 households, 3,350 individuals with 500 persons able to bear arm. [There are the following officials] the commandant of Jingjue, the leaders of the left and the right and an interpreter-in-chief.” [Source: Hanshu, chapter 96a, translation from Hulsewé 1979]

Niya became part of Loulan Kingdom by the third century. Towards the end of the fourth century it was under Chinese suzerainty, later it was conquered by Tibet. In 1900, Aurel Stein excavated several groups of dwellings at Niya, and found 100 wooden tablets written in A.D. 105. These tablets bore clay seals, official orders and letters written in Kharoshthi, an early Indic script, dating them to the Kushan empire. Other finds include coins and documents dating from the Han dynasty, Roman coins, an ancient mouse trap, a walking stick, part of a guitar, a bow in working order, a carved stool, an elaborately-designed rug and other textile fragments, as well as many other household objects such as wooden furniture with elaborate carving, pottery, Chinese basketry and lacquer ware. Aurel Stein visited Niya four times between 1901 and 1931. [Coordinates: 38.021400°N 82.737600°E]

A joint Sino-Japanese archaeological excavations at the site launched in 1994 found remains of human habitation including approximately 100 dwellings, burial areas, sheds for animals, orchards, gardens, and agricultural fields. They have also found in the dwellings well-preserved tools such as iron axes and sickles, wooden clubs, pottery urns and jars of preserved crops. The human remains found there have led to speculation on the origins of these peoples. Some archeological findings from the ruins of Niya are housed in the Tokyo National Museum.[1] Others are part of the Stein collection in the British Museum, the British Library, and the National Museum in New Delhi.

Miran (500 kilometers south of Turpan, (between Niya and Dunhuang) is situated where the Lop Nor desert meets the mountains on the southern Silk Road, According to the International Dunhuang Project: “Over two thousand years ago, a river irrigated the desert and the settlement developed as an early centre of Buddhism in the kingdom of Kroraina. Many monasteries and stupas were built, decorated with murals and sculptures. After the 4th century, Kroraina declined and Miran was abandoned. It was not until the conquering Tibetian armies arrived in the mid-8th century that it was occupied again. Miran lay on a mountain pass over which the Tibetan armies crossed into Central Asia, and was an ideal location for them to establish a garrison. They built a substantial fort and the community of soldiers and their families restored the old irrigation system. This settlement remained there until after the Tibetan Empire crumbled in the mid-9th century. [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition]

Xuanzang Arrives Back in Chang’an

Sally Hovey Wriggins wrote: “When the pilgrim arrived at Chang’an in 645 the emperor Taizong (626-649) was away on a military expedition, so high officials met him and guided him into the capital. A procession of monks carried his 657 books, gold and sandalwood images, and relics through the city. The streets were filled with vast crowds welcoming him home. Subsequently he went to Luoyang where the Emperor Taizong asked about the rulers, climate, customs, products and histories of the countries he had visited. First the emperor exhorted him to be one of his advisors on Asian affairs."If your Majesty orders me to return to secular life, it would be like dragging a boat from the water to the land."After Xuanzang refused,the emperor suggested that he write a book about the Western Regions which Xuanzang completed in 646 CE." [Source: “Xuanzang on the Silk Road” by Sally Hovey Wriggins mongolianculture.com \~/]

Der Huey Lee of Peking University wrote: “Traditional sources report that Xuanzang's arrival in Chang'an was greeted with an imperial audience and an offer of official position (which Xuanzang declined), followed by an assembly of all the Buddhist monks of the capital city, who accepted the manuscripts, relics, and statues brought back by the pilgrim and deposited them in the Temple of Great Happiness. It was in this Temple that Xuanzang devoted the rest of his life to the translation of the Sanskrit works that he had brought back out of the wide west, assisted by a staff of more than twenty translators, all well-versed in the knowledge of Chinese, Sanskrit, and Buddhism itself. Besides translating Buddhist texts and dictating the Da tang xi yu ji in 646, Xuanzang also translated the Dao de jing (Tao-te Ching) of Laozi (Lao-tzu) into Sanskrit and sent it to India in 647. [Source:Der Huey Lee, Peking University, China Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/xuanzang ^^]

Kunlun Mountains

The Kunlun Mountains comprise one of the longest mountain chains in Asia, extending for more than 3,000 kilometers (1,900 miles). In a broad sense, the range forms the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau south of the Tarim Basin. Located in Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang, the Kunlun Shan sits to the south of the Gobi Desert, the Tarim Basin, Taklamakan Desert, the Altyn Tagh. and the Tibet-Xinjiang highway. The range has very few roads and in its 3,000 km length is crossed by only two. In the west, Highway 219 traverses the range en route from Yecheng, Xinjiang to Lhatse, Tibet. Further east, Highway 109 crosses between Lhasa and Golmud. [Range coordinates: 36°N 84°E]

The definition of the Kunlun Shan range varies and the origin of the name appears to come from a semi-mythical location in the classical Chinese text Classic of Mountains and Seas.. Ancient sources use the term to refer to a mountain belt in the center of China, taken to mean the Altyn Tagh and the Qilian and Qin Mountains. The great ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian (Records of the Grand Historian, scroll 123) said that Han Emperor Han Wudi (ruled 141-87 B.C.) sent men to find the source of the Yellow River and gave the name Kunlun to the mountains at its source. [Source: Wikipedia]

From the Pamirs of Tajikistan, the Kunlun Mountains run east along the border between Xinjiang and Tibet to Qinghai province. A number of important rivers flow from the range including the Karakash River ('Black Jade River') and the Yurungkash River ('White Jade River'), which flow through the Khotan Oasis into the Taklamakan Desert. Altyn-Tagh or Altun Range is one of the chief northern ranges of the Kunlun. Its northeastern extension Qilian Shan is another main northern range of the Kunlun. The main extension in the south is the Min Shan. Bayan Har Mountains, a southern branch of the Kunlun Mountains, forms the watershed the Yangtze River and the Yellow River basins.

The Kunlun Mountains highest point is 7,167 meter (23,514 foot) -high Liushi Shan (the Kunlun Goddess in the Keriya area in western Kunlun Shan. Some say the Kunlun extends to northwest and includes 7,649-meter-high Kongur Tagh and 7,546 meter-high Muztagh Ata but the these mountains are more associated with the Pamirs and kind of stand by themselves anyway. The Arka Tagh (Arch Mountain) lies in the center of the Kunlun Shan; its highest points are Ulugh Muztagh (6,973 m) and Bukadaban Feng (6,860 m). In the eastern Kunlun Shan the highest peaks are Yuzhu Peak (6,224 m) and Amne Machin [also Dradullungshong] (6,282 m); the latter is the eastern major peak in Kunlun Shan range and is thus considered as the eastern edge of Kunlun Shan range.

Geology and Mythology of the Kunlun Mountains

The Kunlun mountain range formed at the northern edges of the Cimmerian Plate during its collision, in the Late Triassic (237 million to 201 million years ago). with Siberia, which resulted in the closing of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean. The Kunlun are not volcanic mountains, but over 70 volcanic cones have been counted there, with the highest one being 5,808 meters (19,055 feet) highest, making them the highest volcano in Asia and China and second highest in the Eastern Hemisphere (after Mount Kilimanjaro). The last known eruption was in May 1951. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kunlun is originally the name of a mythical mountain believed to be a Taoist paradise. The first to visit this paradise was, according to the legends, King Mu (976-922 B.C.) of the Zhou Dynasty. He supposedly discovered there the Jade Palace of the Yellow Emperor, the mythical originator of Chinese culture, and met Hsi Wang Mu (Xi Wang Mu), the 'Spirit Mother of the West' usually called the 'Queen Mother of the West', was the object of an ancient religious cult which reached its peak in the Han Dynasty.

The Kunlun mountains (spelled "Kuen-Lun" in the book) are described as the location of the Shangri-La monastery in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by English writer James Hilton. The mountains are the site of the fictional city of K'un Lun in the Marvel Comics Iron Fist series and the TV show of the same name.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020