TURPAN

Turpan (200 kilometers, southeast of Urmuqi on a nice, new highway) was an important oasis during the Silk Road days. Today Turpan is primarily Uyghur agricultural town with a few Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Tadjiks and Han Chinese. The people that live in Turpan are renowned for their longevity. Turpan is also famous for it grapes. The fields and orchards around the town in the Turpan Depression are as green and bountiful as ever with some oddly places chateaus and vineyards. Because it is often so hot in the day Turpan comes alive at night.

Turpan (Turfan) lies on the northern edge of the Turpan Depression (See Below). Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “It’s at the heart of a region that Le Coq described as “a gigantic bowl filled in the center with moving sand.” The evening I arrived, the city radiated neon: hotel arches shimmering, boulevard trees sheeted in blue fairy lights, LED icicles gleaming from lampposts. Las Vegas in Xinjiang. Chinese tourists like to visit Turpan for the city and its sights but also for the nearby desert, where in the summer ground surface temperatures can rise above 150 degrees Fahrenheit, for “sand therapy” — they are buried in burning hot sand to treat conditions such as rheumatism. One participant in a 2018 sand-therapy study in Xinjiang said, “I suffered pain, so it will work.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“The Brutalist concrete architecture of downtown Turpan could be anywhere in China, but in certain districts, an older city still survives, if barely, on side streets lined with ancient poplars. The gateways of houses are painted with Persian flowers or hand-carved with abstract geometric patterns: This is the architecture of Central Asia, of the minority Muslim Uyghur population. The day I visited, the mosque was echoingly empty, the only noise the wind flowing through the grapevines.

“At night, in my hotel in Turpan, I rinsed sand from my skin, sifted it from my clothing and brushed it out of my hair. But always a few grains remained. Wherever I went, the desert came with me. Earlier that day, in the Putaogou district, or Grape Valley, I had watched Turpan’s famous grapevines being “put to sleep” for the winter, their canes cut back and the central trunk coiled around its root. All over the city, farmers were tamping earth and leaves lightly over the vines; what was left looked like graves. I remembered lines from one of my favorite poems, written by Li Bo and translated by Rewi Alley: “We who live on the earth / are but travelers; / the dead like those / who have returned home; / all people are as if / living in some inn, / in the end each and every on / going to the same place.”

Tourist Office: Turpan Tourism Division, 41 Qingnian Rd, 838000 Turpan. Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 995-523-706, fax: (0)- 995-522-768 Web Sites: Lonely Planet Lonely Planet Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Getting There: Turpan is accessible by bus from Urumqi and lies about 50 kilometers from a station on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. This is accessible on the new fast train.

History of Turpan

Located in the Turpan Depression and surrounded by irrigated fields, Turpan was fought over and controlled for 1,500 years by successive waves of nomads, Chinese, Tibetans, Ugyurs and Mongols. About 400 years it began to decline and beginning about a 100 years it was raped of its treasures — frescoes, statues and 2,000-year-old relics — by Western archeologist who carted away their booty to museums in New York, Boston, London and Berlin.

Turpan used to be an important strategic point on the Silk Road. As early as two thousand years ago, a town called Jiaohe was built forth kilometers from today's town of Turpan. Jiaohe then was the capital of the Outer Chshi Kingdom. During the first century, Jiaohe came under the rule of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220). During the sixth century, Turpan was under the administration of Gaochang Kingdom. During the reign of Emperor Tai Zong (626-649), the Gaochang Kingdom was conquered by the Tang Dynasty (618-906), and Turpan again became a frontier town of China, serving as a stopover for merchants, monks, and other travelers on their way to the west.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “The Uyghurs emerged as a regional power around A.D. 750 in what is now Mongolia. Turpan has been a Uyghur city since the ninth century, when the Uyghurs migrated to the area and started the kingdom of Qocho. It was a kingdom, the archaeologist J.P. Mallory and the Sinologist Victor H. Mair wrote in their 2000 book “The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples From the West,” that once “combined, apparently harmoniously, a myriad of different ethnic groups, religions and languages.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Xuanzang in Turpan

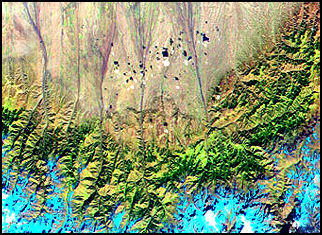

satellite image of

Taklamakan Desert In A.D. 629, early in the Tang Dynasty period, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan Tsang) left the Chinese dynasty capital for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He traveled west — on foot, on horseback and by camel and elephant — to Central Asia and then south and east to India and returned in A.D. 645 with 700 Buddhist texts from which Chinese deepened their understanding of Buddhism. Xuanzang is remembered as a great scholar for his translations from Sanskrit to Chinese but also for his descriptions of the places he visited — the great Silk Road cities of Kashgar and Samarkand and the great stone Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. His trip inspired the Chinese literary classic “Journey to the West” by Wu Ch'eng-en, a 16th century story about a wandering Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit. It is widely regarded as one of the great novels of Chinese literature. [Book: "Ultimate Journey, Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk Who Crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment" by Richard Bernstein (Alfred A. Knopf); See Separate Article on Xuanzang]

Xuanzang stayed in Turpan for some time. The king there was enchanted by the monk's knowledge of the sacred Buddha books, refused to let him leave, only reluctantly relenting when Xuanzang threatened a hunger strike. Thus, Xuanzang had peaceable conquered to royal will. The king gave him letters of introduction the rulers of the oases along the way, thereby providing the assistance that made his pilgrimage successful." [Source: Irma Marx, Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com]

Sally Hovey Wriggins wrote: “Several months after Xuanzang visited Hami, the kingdom reverted back to China. Like many another oasis it was caught between the depredations of Turkic nomads from the north and Chinese conquerors to the south and east. Xuanzang's reputation preceded him. When Xuanzang was still at Hami, the king of Turfan sent an escort to conduct him to his kingdom, some 200 miles to the west. The king of Turfan was a powerful monarch with great influence throughout the Taklamakan desert, and happily for Xuanzang, he was also a devout Buddhist. The king's subjects in the ancient kingdom of Turfan were neither Chinese nor Turks nor Mongolians, but an Indo-European people speaking a dialect of the Tocharian language. The government's institutions however, were based on Chinese models. Reflecting this composite culture, modern excavations around Turfan have brought to light Christian, Nestorian, Manichean and Buddhist manuscripts, sculptures and paintings. Bezeklik monastery in the nearby mountains contained sixty-seven (some say fifty seven caves) dating from the fourth to the fourteenth century. [Source: “Xuanzang on the Silk Road” by Sally Hovey Wriggins, author of books on Xuanzang, mongolianculture.com \~/]

“The king was so attracted to Xuanzang that he tried to detain him by force. Xuanzang staged a hunger strike; the king relented. Once convinced of his determination, the king equipped him with gold, silver, rolls of taffeta and satin, 30 horses, and 24 servants. More important, he gave him 24 letters to be presented to the kingdoms he would pass through. Finally, he commissioned one of his officers to conduct him to the Great Khan of the Western Turks. Xuanzang was overcome by his generosity. Well he might have been, for the Empire of the Western Turks at that time extended from the Altai mountains in the former Soviet Union to what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan.” \~/

See Separate Article XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN WESTERN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN AFGHANISTAN factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN INDIA (630-645) factsanddetails.com

Sights in Turpan

Turpan Museum (in Turpan) has items from the Tang dynasty excavated from the Astana Graves which are located outside the town. Items include ancient silks, clothes and preserved corpses. Ethnic Chinese mummies discovered in the region are on display. In an ancient graveyard in Astana, near Turpan, a man and a woman are buried together in an underground crypt that dates from the Tang Dynasty(A.D. 618-906) and is one of the few places that the public can see mummies in their original graves. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The woman looks younger than the man. Her mouth is in a grimace; forensic specialists say her arm and neck were broken shortly before her death. "We think she might have been beaten and buried alive to be with her husband. He died naturally,'' said Bai Yingcai, a tour guide and mummy expert who was taking visitors through the crypts.

Turpan’s Bazaar mainly has local products such as grapes and melons and modern goods but still has a bit of old time atmosphere. This Central-Asian-style bazaars sell embroidered handbags, handmade knives, shish kebabs, watermelons, about twenty kinds of dried fruit, almonds, walnuts, and mutton. Mud-brick houses still predominate. In his 1995 book “Frontiers of Heaven: A Journey to the End of China,” the travel writer Stanley Stewart wrote: “Bathed in a ruby light filtering through the colored awnings which span the lanes, it was crowded with carpets, rolls of silk, coils of rope, saddlebags and endless piles of green grapes. The men wore tall boots, long coats, daggers and embroidered caps.” Acrobats, card trick magicians and fire-eaters still perform before old men in skull caps, women in headscarves and barefoot children with matted hair.

Prefect Sulaiman Minaret (three kilometers southeast of Turpan) was built during the Qian Long reign (1736-1795) of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). A tablet beside the minaret bears an inscription in the Han and Uygur languages. It was erected By Sulaiman, a ruler of Turpan, in memory of his father, Emin, during the mid-eighteenth century, so the structure is also called the Emin Minaret. The slim, round minaret is forty-four meters tall and was built of yellow bricks with flower patterns. The exquisitely formed minaret with its helmet-shaped top is one of the most famous examples of Muslim architecture in Xijiang. Stewart wrote the minaret is “beyond the town, its feet in a green sea of vineyards” and it adjoining mosque is a“columns and arches receded like a trick of mirrors.”

Turpan Depression

Turpan Depression (180 kilometers southeast of Urumqi) is one of the lowest, hottest and driest places on earth. Temperatures of 54̊ C (130̊F) have been recorded along with rainfall of less than an inch a year). The second lowest point on earth (154 meters, 505 feet below sea level) after the Dead Sea is at Aydingkol Lake, a salt lake in the depression with a crystallized salt surface. You would think these conditions would make it one of the most desolate places on earth. But that is not the case.

Nestled between gray eroded hills, the Turpan Depression is one of the greenest and most densely planted valleys in China, famous for its orchards, vineyards, grapes and melons — all made possible by unique karez canals used for over 2000 years and fed by snowbelt and runoff from the 16,000-foot peaks of the Tian Shan range. The deserts around Turpan are a barren mix of black pebbles, boulders, dust patches, and sand. On the east side of the Turpan Depression are huge sand dunes called appropriately enough the Sand Mountains.

The Turpan Depression is a long, narrow stretch of land, covering an area of about 50,000 square kilometers, with Bogda Mountain on the north and Kurultag Mountain on the south. Because of the drastic (five-thousand-meter) difference in height between the highest mountain tops around the depression and the bottom of the depression, the scenery, varies greatly at different altitudes — from perpetual snow at the summits to green oases at the foot of the mountains.

Turpan is not only special for its low altitude, but also for its strange climate. In summer, the temperature can reach as high as 47ºC (117ºF), while on the surface of the sand dunes, it may well be 82ºC (180ºF). It is no exaggeration to say that you can bake a cake in the hot sand. The average annual rainfall is little more than ten millimeters; sometimes there is not a drop of rain for ten months at a stretch. Days are exceptionally sunny throughout the year; but people say it is not difficult to endure the heat of the day when you known the night will be cool. The hot, dry climate is especially beneficial to sweet crops. Fruit trees, melons, and particularly grapes grow very well in the Turpan Depression. Every year, more than a thousand tons of grapes are exported to foreign countries.

Turpan: Grape Valley in the Volcano

On the western side of the Flaming Mountains in the Turpan Depression, Grape Valley is crisscrossed by irrigation ditches and dense with trees. As the climate there is moist and cool, the valley is a pleasant place to visit in summer. The seedless grapes produced in the valley are excellent.

According to China’s Central University for Nationalities: “The area of Turfan in Xinjiang has been called 'Fire Land' from ancient times. This name originated from the Volcano. Speaking of Volcano, people will always think of the well-known Chinese traditional novel: The Road to the West. It is said that in this novel the story happened in Volcano when the hero named Tan Sanzang couldn't climb over this hill while his disciple named Sun Wukong put out the overwhelmed fames using the Palm-leaf fan borrowed from the TieShan Princess. Thus, all the tourists from far away places would love to see this famous magic hill with a long history when they come here. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

“The Volcano locates in the center of the Turfan Valley. Actually, it is the branch of Tian Shan Mountain that has totally approximately 100 kilometers long from the East to the West and has about 10 kilometers wide, with an average latitude of around 500 meters. It has the color of deep red since the body of the hill is consisted of the red mud of the mud stone, sand stone from the third period in the Mesozoac Era. All the mountains wind its way gorgeously and are covered with many stormed cracks. The hills are rocky without any grass. Every summer, the earth temperature is up to 60-70 in centigrade in the strong sunshine. Seen from far away, the red body of hills is surrounded by the hot fuses and the arising red clouds as if it is burning with fire. That's how Volcano got its name. The Uyghur people name it Wuzegetage, which means the red hill. There is a popular story like this: The Red Hill was once an evil dragon. It damaged people's houses and lands at its will and killed the people and the cattles. The brave young fighter named Halahezhuo determined to kill it for the people. With a powerful sword in his hand, he finally cut the evil dragon into pieces after violent fights. The dead body of the dragon was turned into red by the blood running out and became a huge red hill. Every cut in its body has become the valleys in the mountains. Those valleys still remain the 'cuts of the sword' in dark blue. That formed the Grape Valley, Wood Valley, Peach Valley and Tuyu Valley with beautiful sceneries. Every summer, they are surrounded by the brooks and shadowed by the green trees. Among them, the Grape Valley is especially known for its abundance in sweet grapes.

“People who come to Turfan will never miss visiting the famous Grape Valley. It lies in the Volcano Valley 13 kilometers to the northeast of Turfan City. In summer, you can see the miles of green grape lands layer after layer along both banks of valley about 8 kilometers long. Among them the wines cross together and are arranged in a neat order. The rural cottages are surrounded by the clear brooks. Under the huge and tight grape frames, piles and piles of grapes have shapes in round, long, have colors in white and red alike rubies and gedeite. You will be intoxicated by their full body, crystal color and scent smell. Although in Volcano Valley it is unbearably hot with arising heat everywhere, the Grape Valley is still very cool with comfortable winds. That's why it can be called the oasis of the Fire Land as a cool place escaped from the hot in summer.

“Nowdays the Grape Valley grows the famous seedless white grapes plus with the red grapes, Manaizi Grapes, Keshehaer, Bijiagan and the black grapes. The seedless white grapes has the advantages of the sustainability from the dryness and the salty soil, the length of age up to 100 years. Also the grain is big while the fruit is small, is juicy and seedless, easy to eat fresh or more suitable to be made into the dry grapes. It is called the China Green Pearls at international markets. The Turfan winery in the Grape Valley produce many kinds of good-quality wines, among which the whole juice wine is greatly needed all over the country.

“Deep into the Grape Valley, there is a specially designed Grape Garden for all the Chinese and foreign tourists. In the grape corrider shadowed by the piles of greens which shed from the sunshines, you can play with the cool spring water, taste the delicious grapes. It will give you a fantastic feeling as if you were in a wonderland.

Karez Wells

Karez tunnel Karez wells are a type of underground irrigation system that uses special wells which are linked by underground tunnels and provide irrigation in the desert. They underlie large areas of Turpan depression. One of the ancient world's great engineering feats, the system is comprised of underground canals and boreholes that carry water — from melted snow, springs and water tables under hills — from the highlands to farming areas. The world-famous grapes of Xinjiang own their excellence to the existence of these wells.

Karez Wells were nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008. According to a report submitted to UNESCO: “The Karez wells in the Turfan area totaled up to over 1100 sets, among which 538 sets are in Turfan city, 418 sets in Shanshan and 180 sets in Toksun. The annual runoff volume of these Karez wells amounts to 294 million cubic meters which accounts for 30 percent of the total irrigated areas in Turfan area. [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

The total length of the wells in Turfan. amounts to more than 3,000 kilometers with an annual runoff surpassing the total runoff volume of the Flaming Mountain water system. The karez system in Xinjiang ranks with the Great Wall of China and the Grand Canal in terms of time and labor spent building it and may exceed them as an engineering feat. The tunnels carry water, much of originally snow melt from the Tian Shen Mountains, to oases like Turpan.

Turpan Karez Water Museum (near Jiaohe) features an example of a Qing-dynasty tunnel. Since the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), water has been brought into the Turpan area by the ingenious Karez irrigation system. Beginning in the Flaming Mountains (Houyan Shan), underground water channels were cut in a gentle slope to bring meltwater down to the region. Web Site: Wikipedia Wikipedia

How Karez Wells Work

The karez wells were sunk at varying distances to a dozen or several dozen meters deep to collect undercurrent water from melting snow. The water is then channeled through tunnels dug from the bottom of one well to the next and led to oases for irrigation. Most of such irrigation tunnels stretch for some three kilometers, but some extend as far as thirty kilometers.

Karez wells follow slopes down hill and are built underground so the water doesn't evaporate in the hot sun. From the sky they look like a long rows of gopher holes, giant anthills or donuts. The holes are outlets for vertical shafts that provide ventilation, and a means of excavating material. Dirt is piled around the entrances to prevent potentially-eroding rainwater from entering the system. Most of the holes are about three to 10 meters (10 to 30 feet) deep but some drop down almost 30 meters (100 feet).

According to the report submitted to UNESCO: “The length of the Karez wells varies with the geographical environment. A Karez well generally consists of four parts: the open channel, the underground channel, the vertical well and the small reservoir. The underground channel constitutes the main body of the system, which is in fact the underground watercourse. The vertical well functions as the outlet for the shipping out of mud and gravels. The water outlet of the underground channel is called "dragon mouth", which is in connection with the open channels above ground. The water of the Karez wells empties into the small reservoir before it is drawn into the channels.” [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

History of Karez Wells

Karez technology was imported from Persia (Iran), where the underground canals are called qanats. The tunnels have traditionally been communally owned, with villagers splitting the cost of building and maintaining them. In wells nourished the crops, nurtured people in the oasis and provided water sources for Silk Road merchants and caravans who are traveling through the great desert.

Some date back to the time of Alexander the Great. This method of irrigation was passed on to Xinjiang people during the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) (206 B.C.-A.D. 24). By one estimate more that 5,000 kilometers of wells were constructed, with about 60 percent of them still in use today. This great irrigation project was initiated by the ancient people, benefiting both the contemporaries and later generations.

According to the report submitted to UNESCOby the Chinese government: “Historical documents show that the sinking method of the Karez wells inside Xinjiang including the Western Region was introduced by the Han people. The majority of the ethnic minorities of the northwest borderland hadn't mastered the sinking technology by that time. It was Lin Zexu that stood out among all the people who advocated and promoted the Karez wells as the most powerful and influential one in modern times. Ever since then the Karez wells have been part of the irrigation works. [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

“Karez wells are a successful application of the sinking technology of the Central Plains in the Turfan area. It is a historic inheritance and promotion of the sinking technology of the Central Plains, and plays a very important role in the study of the sinking technology both in the Central Plain and in the Middle and West Asia.” This view seems to Sinocentric. Couldn’t the technology have been introduced from Central Asia or Iran.

Making and Maintaining the Karez Wells

Karez wells have largely been dug by hand from head wells on high ground near the source of the water to places where the water is used. It is believed millions of hours of forced labor was needed to build them. The long, downward slopping tunnels were dug using the vertical holes to reach the underground tunnel from the surface.

Digging the tunnels and maintaining the karez system is hard and dangerous work. The men who do the digging, repairing and cleaning have traditionally been highly skilled and well paid. To repair the tunnels workers climb down holes from the surface to the underground tunnels. There they clean out the tunnels and stabilize weak sections with ceramic hoops. The work is often done by lantern light in extremely cramped conditions — most of the tunnels are barely large enough for a man to crawl through.

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: Karez well can realize irrigation by water flowing automatically, which means low cost in running the system. It reduces evaporation, and avoids contamination caused by sand storm, to ensure the regular flow of irrigation water. It is stable in runoff volume and good in water quality to meet the standard for drink and irrigation. The technological requirement for the construction of the Karez well is not very high, and there is no lining for protection. The cover material is very simple and handy in local places with rather low cost. The total length will surpass 4400 kilometers which is longer than the Yellow River, which is the "cradle river". [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

“As an ancient irrigation system, the Karez well system has ever played a very important role in the daily life and in the production of the people in Turfan area. Though there is highly advanced electromechanical irrigation system, the function and position of the Karez system can not be superseded completely.”

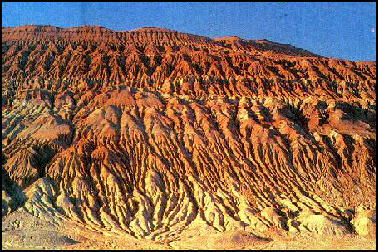

Flaming Mountains

Flaming Mountaining (25 kilometers east of Turpan) are a 500-meter-high ridge of mostly red and yellow sandstone that covers an 10-by-100 kilometer area. In the evening and early morning, the mountain's colorful, wind-carved faces are set ablaze by the setting and rising sun. During the day, they are not quite so spectacular, and instead look like gray eroded badlands.

The Flaming Mountains have recorded some of China's highest temperatures (70̊C,160̊F in the sun), another reason why they are called "flaming." All Chinese schoolchildren know the Flaming Mountains from its association with the classical novel “Journey to the West, which traces the travels of a Chinese monk and his sidekick Monkey Sun Wukong. On the east side of the Turpan Depression are huge sand dunes called appropriately enough the Sand Mountains.

The Flaming Mountains cross the Turpan Depression from east to west. Their average height is 500 meters (1,600 feet), with some peaks reaching over 800 meters (2,600 ft).Parts of the Flaming Mountain are below sea level. They were described in the Journey to the West as one of the most dangerous obstacles in the path of Monk Xuan Zang and his disciples as they traveled west to obtain the Buddhist sutra.

Silk Road Sites in the Turpan Area

Silk Road Sites in the Turpan Area: 1) Ancient City of Jiao River, Turpan City (Coordinates: N 42 25 22-42 25 26, E 89 03 15-89 03 58); 2) ) Ancient City of Gaochang and Astana Cemetery, Turpan City (Coordinates: N 42 50 21-42 51 19, E 89 30 49-89 32 17); 3)Taizang Tower, Turpan City (Coordinates: N 42 52 03, E 89 31 36); 4) Bezeklik Grottoes, Turpan City (Coordinates: N 89 32 10-89 33 54, E 42 56 41-42 57 37); 5)Toyuk Grottoes, Turpan City (Coordinates: N 89 41 39-89 41 40, E 42 51 50-42 51 51)

Toyuk (about 25 kilometers east of Gaochang) is a Muslim pilgrimage center at at the base of the Flaming Mountains. Shrines in the area honor the first Uighur ruler to convert to Islam, as well as a local version of the legendary Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. The village's main mosque has a green roof and dome. In the area are many building with pierced walls that is used for drying grapes to make raisins. Raisins are one of the major products of the region. The Buddhist grottoes at Toyuk (also spelled Toruq and Tuyuk) date from the 5th to the 10th centuries AD, when the Uighurs converted to Islam. The river, winding down from the mountains, would have provided water and greenery to sustain the resident monks. [Source: art-and-archaeology.com]

Taizong Tower (40 kilometers east of Turpan in Sanb Oxiang, near Gaochang and Astana Tombs) looks like an eroded mud-brick apartment building. Reaching height of 20 meters, it has Buddhist shrines on all four sides. Prior to its collapse, the Sirkip Tower was also constructed in similar fashion. Scholars suggest the structures were tied to the ancient city of Gaochang. [Source:farwestchina.com]

According to farwestchina.com: “If the Astana Tombs are of interest to you, you can stop there before heading out to Taizang Tower or the ancient city of Gaochang. However as Taizang Tower is absent from travel guides, it may take some exploring on your part to discover this site on your own. You need to hire a private taxi to visit Taizang Tower. Rates depend on the size of your party and how many places you would like to visit on the way, but generally you can push to have a standard taxi take you to Astana, Gaochang, and Taizang Tower for 400-600 RMB. Entry Fee: When I visited, the gate was locked and visitors were not permitted inside. I was told that the entry fee used to be 30 RMB. Information I found indicated a man across the street held the key and would let us in, but after much negotiating he wouldn’t allow it. Fortunately, even if you come up against the same problem, it’s still possible to walk around the perimeter of the tower.”

Gaochang

Gaochang (45 kilometers east-southeast of Turpan) is an ancient city founded in the 1st Century B.C. and abandoned by the end of the 13th century. Situated at the foot of the Flaming Mountains, and best visited around sunrise, Gaochang rests on two million square meters of rammed earth and consists of three parts: The inner city, the outer city and the palace city.

The outer city wall is 6.5 kilometers (four miles) around and the inner city wall is 3 kilometers (two miles) around. There is a high terrace with a 50 foot high structure called "Khan's Castle" and there are remains of temples in the southwest and southeast corners of the city. Over the centuries Gaocheng controlled by Muslims, Buddhist and even Manichaeans and Nestorian Christians.

Scattered over an area of two million square meters, Gaochang City was the political and cultural center in China's northwest for 1,500 years from the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), when the government began to station garrisons there, until the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), when the city began to deteriorate. Most of the city walls are still well preserved, the highest section being twelve meters high. Within the city walls are the remains of broken houses, earth pagodas, and a network of streets. Most of the houses were built with rammed earth or mud bricks, with arched doorways and windows.

According to the International Dunhuang Project: Gaochang: The Tarim Basin lies north-west of Dunhuang across the Gobi Desert. It is the second lowest place on earth with the Heavenly Mountains rising to its north. Meltwater, fertile soil and searing heat produce fine crops here, especially grapes. From the 5th century the capital was at Gaochang, a large walled city. The area fell under the control of several nomadic powers before being conquered by the Chinese in 640. Two centuries later it was taken by the Uyghurs, a confederation of Turkic tribes who called the capital Kocho. The plain north of Gaochang, known as Astana, was used as a cemetery from the late 4th century. Almost all the manuscripts from the tombs are in Chinese, but Manichaean texts in Sogdian and Uyghur and numerous Buddhist texts in various languages have been found in the ancient city itself." ^/^

Astana-Karakhoja Ancient Tombs (between Turpan and Gaochang) contains the burial mounds of noblemen and the tombs of common peoples. Scattered over a 10-square-kilometer area, the cemetery contains three underground tombs that are open to the public. Two of them contain 600-year-old corpses that visitors can examine and photograph. Theroux wrote they are "perfectly preserved, grinning, lying side by side on a decorated slab." Mummified corpses, more than 1000 years old, have been unearthed from more than 500 tombs.

Jiaohe

Bezeklik

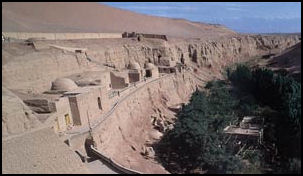

Jiaohe (10 kilometers west of Turpan) is another ancient city. Last inhabited in the 15th century, it was a Silk Road caravan stop, and an important Buddhist center, as evidenced by the ruins of hundreds of temples, monasteries and shrines found there today.

Set upon a 100-foot-high boat-shaped plateau sided by two dry rivers, flood plains, and cultivated fields, Jiaohe contains a residential area with a clearly defined wide avenue, chiseled into the plateau; a ruined grand palace near the plateau's stern; and a temple complex with unique prong-shaped central shrine surrounded by 100 smaller shrines, grouped into four checkerboard squares containing twenty-five shrines each.

Archaeologists believe that the plateaus was inhabited by esteemed Buddhist monks and upper class families while peasants tended farms in the surrounding lowlands. It is believed the city reached it peak during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220). A thousand or so years later, the city was sacked by Moslem invaders who defaced many of the Buddhist's monuments.

These ruins are considered to have been the frontier post of the outer Cheshi Kingdom during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220). In the sixth century Jiaohe Prefecture was established with the original Jialhe City as the seat of the prefectural government. Jiaohe City was built on an island at the confluence of two rivers, occupying an area of 230,000 square meters. Most of the remaining buildings are from the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and later times, and they fall into three categories: temples, civilian residences, and administration buildings.

What is left of the town indicated three interesting things about it: (1) that its doors and windows did not face the street-a peculiarity of Tang Dynasty (618-906) architecture: (2) that courtyards and rooms were dug from the earth, like cave dwellings — a specialty in China's northwest; and (3) that no city walls were necessary because the town was surrounded by cliffs — a feature decided its peculiar terrain. The fact that Jiaohe's houses have been preserved so well is mainly due to the area's dry climate.

Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

Uighur Princes from Bezeklik Caves

Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves ( 50 kilometers east of Turpan) is situated in the cliffs of the Mutougou Valley. The caves were a Buddhist center from the 6th century to the 13th century. Forty of the 77 caves contain murals. The best works however were carted off by Western archaeologists. Bezeklik is a former Buddhist retreat. Domed monasteries carved into cliffs in the forth century are currently being or have recently been restored .

These caves are among the best known grottoes in Xinjiang. Built during the late Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-581), the grottoes are known mainly for their murals, which still retain their fresh, bright colors though bits and pieces are missing here and there. The themes of the paintings are taken mostly from Buddhist tales. Influence from western regions in China and Central Asia are strongly evident in the artistic style of these murals.

Shengjinkou (forty kilometers north of Turpan) contains ten mud-brick caves that were part of a Buddhist temple during the 7th to 14th centuries and was founded during the Tang Dynasty (618-906). The murals on the cave walls depict lotus blossoms with cloud patterns, a lone crown on dry tree branches, vines laden with grapes, rows of willow trees, and Buddhist portraits. Most of the paintings are accompanied by annotations in the Urgur language. Other discoveries at this site include Buddhist scriptures written in Sanskrit and Han languages, and coins of the Tang Dynasty (618-906).

Loulan

Loulan(east of Turpan, eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert) is an oasis town on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, where the northern and southern branches of the Silk Road came together, and near the Lop Nur nuclear testing site. The kingdom of Loulan thrived for 700 years beginning in the 2nd century B.C. It was renamed Shanshan ) after its king was assassinated by an envoy of the Han dynasty in 77 B.C.. It is famous its mummies with Caucasian features. There isn't much to see in the area.

Loulan (also known as Kroraina) ruled a string of oases that stretched east of Khotan through the Taklamakan and Lop deserts. According to the International Dunhuang Project: “They flourished in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. By the 7th century many had already met their demise and reverted to the desert, possibly because of climate change. In the extreme aridity of the Taklamakan desert climate, whole landscapes of abandoned towns and farmsteads with their vineyards and orchards still standing were swallowed up by drifting sand dunes.

Most of the discoveries come from the Xiaohe tombs there. The Xiaohe Tombs were discovered in 1934 by a Swedish explorer and excavated by a Chinese team starting in 2000. They have been dated as being between 3,000 and 4,000 years old, making them between 2,000 and 1,000 years older than the Loulan Kingdom. Strange pools ring the Xiaohe Tomb site.

The most famous mummy unearthed in the Taklamakan desert is that of woman with long reddish blonde hair. Discovered near Loulan in 1979 and nicknamed the "Loulan Beauty," she was five feet tall, possessed a high nose, and was buried wearing a goatskin wrap, woolen cape, leather shoes and a hat trimmed with goose feathers. Carbon-dating indicates that her body is 3,800 years old but similar tests of the wood of the coffin of mummy found nearby suggest that she could be 6,000 years old. See Minorities, Minorities in Xinjiang, Early History

See Separate Article TARIM MUMMIES factsanddetails.com

Loulan Beauty

Loulan Beauty

Loulan Beauty (now in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum in Urumqi) is the most famous mummy unearthed in the Taklamakan desert. Discovered near Loulan in 1979 and nicknamed the "Loulan Beauty," she has long reddish blonde hair was five feet tall and was buried wearing a goatskin wrap, woolen cape, leather shoes and a hat trimmed with goose feathers. Carbon-dating indicates that her body is 3,800 years old but similar tests of the wood of the coffin of mummy found nearby remotely suggest that she could be 6,000 years old. She is also known as the Xiaohe Princess.

The Loulan Beauty was unearthed in 1980 by Chinese archaeologists who were working with a television crew on a film about the Silk Road near Lop Nur, a dried salt lake 120 miles from Urumqi that has been used by the Chinese for nuclear testing. Thanks to the extreme dryness and the preservative properties of salt, the corpse was remarkably intact — her eyelashes, the fine hair on her skin, even the lines on her skin were visible. She was buried face up about 3 feet under, wrapped in a simple woolen cloth and dressed in a goatskin, a felt hat and leather shoes. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “What was most remarkable about the corpse was that she appeared to be Caucasian, with her telltale large nose, narrow jaw and reddish-brown hair. The discovery turned on its head assumptions that Caucasians didn't frequent these parts until at least a thousand years later, when trading between Europe and Asia began along the Silk Road. Since Uyghurs themselves often resemble Europeans rather than Chinese, many were quick to adopt the Beauty of Loulan as one of their own." "If you went to see the mummy in the museum, a Uyghur would come up to you and whisper proudly, 'She's our ancestor,'" said Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese studies at the University of Pennsylvania. "It became a political hot potato." [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

Despite her fine features, lived a hardscrabble life. Her shoes and clothing had repeatedly been mended. Her hair was infested with lice. She had ingested a considerable amount of sand, dust and charcoal, and lung failure most likely caused her to die in her early 40s. "You can see that even back then, pollution was a problem," said Wang. [Ibid]

Xiaohe

Xiaohe(300 kilometers south of of Turpan) means "Small River". Small River Cemetery No. 5 (SRC5), a 20-foot-high, man-made sand mound in Xiaohe, is the oldest and most intriguing Tarim mummy site. Found in 1934 but then forgotten, is located very remote, restricted desert in Lop Nur in the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang where China once conducted nuclear tests. Rediscovered in 2000, the site was completely excavated in the early 2000s to protect it from looters. Under the sand archeologists excavated five layers of burials and 167 graves, revealing over 1,000 objects and 30 well-preserved desiccated corpses and mummies, the oldest dating to around 2000 B.C. The mummies were buried in coffins shaped like overturned boats. Sexual iconography was everywhere at the site: in the coffins and on posts representing phalluses and vulvas placed in front of each grave. Under the sand near the tops of the mound were nearly 200 poplar posts, up to four meters high—a considerable amount of lumber for a remote desert sitr. Some of the posts, painted black and red, were either torpedo-shaped or resembled oversized oars. The bodies were situated under the boat-like coffins wrapped in cattle hides. [Source: Mary Mycio, Slate.com, February 14, 2013, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology]

The entire Xiaohe Tomb complex contains about 330 tombs, about 160 of which have been looted by grave robbers. Nicholas Wade wrote in the New York Times, “In the middle of a terrifying desert north of Tibet, Chinese archaeologists have excavated an extraordinary cemetery. Its inhabitants died almost 4,000 years ago, yet their bodies have been well preserved by the dry air. Their remains, though lying in one of the world's largest deserts, are buried in upside'down boats. And where tombstones might stand, declaring pious hope for some god's mercy in the afterlife, their cemetery sports instead a vigorous forest of phallic symbols, signaling an intense interest in the pleasures or utility of procreation. The long-vanished people have no name, because their origin and identity are still unknown. Their graveyard lies near a dried-up riverbed in the Tarim Basin. The mummies are so far, the oldest discovered in the Tarim Basin. Carbon tests done at Beijing University show that the oldest part dates to 3,980 years ago."Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, March 15, 2010 \=]

“The Small River Cemetery was rediscovered in 1934 by the Swedish archaeologist Folke Bergman and then forgotten for 66 years until relocated through GPS navigation by a Chinese expedition. Archaeologists began excavating it from 2003 to 2005. Their reports have been translated and summarized by Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese at the University of Pennsylvania and an expert in the prehistory of the Tarim Basin. As the Chinese archaeologists dug through the five layers of burials, Dr. Mair recounted, they came across almost 200 poles, each 13 feet tall. Many had flat blades, painted black and red, like the oars from some great galley that had foundered beneath the waves of sand. \=\

“At the foot of each pole there were indeed boats, laid upside down and covered with cowhide. The bodies inside the boats were still wearing the clothes they had been buried in. They had felt caps with feathers tucked in the brim, uncannily resembling Tyrolean mountain hats. They wore large woolen capes with tassels and leather boots... Within each boat coffin were grave goods, including beautifully woven grass baskets, skillfully carved masks and bundles of ephedra, an herb that may have been used in rituals or as a medicine." \=\

Lop Nur was once the site of large lake known as "Wandering Lake" because the Tarim River changed its course, causing its terminal lake to alter its location between the Lop Nur dried basin. Satellite photographs show ancient waterways in what is now barren desert, indicating that green oases existed there in ancient times. The lake at Lop Nur measured 3,100 square kilometers (1,200 square miles) in 1928, but after that dried up due to construction of dams which blocked the flow of water feeding into the lake system. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wade wrote: “There are no known settlements near the cemetery, so the people probably lived elsewhere and reached the cemetery by boat. No woodworking tools have been found at the site, supporting the idea that the poles were carved off site. The Tarim Basin was already quite dry when the Small River people entered it 4,000 years ago. They probably lived at the edge of survival until the lakes and rivers on which they depended finally dried up around A.D. 400. Burials with felt hats and woven baskets were common in the region until some 2,000 years ago." \=\

Lop Nor Wild Camel National Nature Reserve is a West-Virginia-size reserve in the Gobi Desert with some of the last populations of wild Bactrian camels, Tibetan asses and argali sheep. Founded in 2000, the reserve contains a remote valley with a spring, where many of animals drink. In the mid 2000s, illegal gold miners invaded the area and left behind barrels of cyanide and other toxic chemicals that fouled the water in the spring and have since been removed. Animals have returned to the spring. Lop Nor is where China tested its first nuclear weapons.

Hami

Hami (400 kilometers east of Turpan) serves as the eastern gateway of Xinjiang if you are coming by train or road from most destinations in China. Hami is famous for its melons and is home to about 600,000 people. Served by fast trains that go as far west as Urumqi, Hami lies near where the Tian Shan Mountain, Gobi Desert, Taklamakan Desert and Turpan Depression all come together. Not far from Hami are deserts, oases, grasslands, lakes, mountains and forests.

A traveler to Hami wrote in CRI: “On the first evening of our stay in Hami, we watched "Maixilaipu"-in Uygur it refers to a song-and-dance carnival party performed on the square by folk artists and professional dancers. Unlike normal ethnic minority dances, the beautiful Uygur girls and handsome Urgur young men invite audience members to dance with them. The warm and festive atmosphere moved everyone. [Source: CRI, June 1, 2009]

“The next day we visited Balikun prairie on the outskirts of Hami. Located at the foot of Tian Shan Mountain, Balikun prairie offers picturestic scenery. The white sheep roaming on the grassland looked like rolling masses of clouds in the crystal-clear blue sky, while green grass, wild blossoms, flocks and herds grazed along the azure-blue lake.”

Traveling Between Dunhuang and Turpan by Road

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: ““I Left Dunhuang the next morning by taxi, heading for Turpan — 500 miles away. An hour into the journey, a distant city floated. I looked at the map, then out my window again, dazed. I wanted to follow the shining line of trees, to walk through the shimmering gateways, to climb those towers. ““Haishishenlou,” said the taxi driver, indifferent. He didn’t even glance out the side window but just looked at me in the rearview mirror. “Illusion.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“My map showed nothing to the east for several hundred miles. In his 1926 memoir “Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan,” translated two years later by Anna Barwell, the German archaeologist Albert von Le Coq wrote that the Uyghurs called this phenomenon azytqa, “misleader,” adding that the mirage “is so lifelike that many inexperienced travelers may very easily follow it.” I would, too, if I had been driving. The nameless city looked far more alluring than the blank asphalt road. The vision traveled alongside the car, as if it were painted on the window glass. I knew, but did not want to believe, that it was unreal.

“Here, the Gobi changed from rosebud pink to black with rare streaks of ivory. The British-Hungarian explorer Marc Aurel Stein, in his 1920 piece for The Geographical Review titled “Explorations in the Lop Desert,” described the towerlike mesas near Dunhuang as quivering “phantom-like in the white haze,” and from a distance, the white bands among dark strata looked like mist rising over a river. But there was no water, just salt scattered along the dunes. In this region, Stein once wrote of “nature benumbed.”

“The British diplomat Eric Teichman pointed out in his 1937 “Journey to Turkistan” that those traveling in the caravans called this area the Four Dry Stages: This road was among the most ferocious, the most fatal relays not just in Central Asia but on the entire Silk Road network. Beyond, springs of bitter water were the only landmarks: Wild Horse Well, Clear Water, One Cup Spring, Muddy Spring, the Well of the Seven Horns.

“These stretches took weeks to cross even in the 20th century: From ancient times until the 1960s, camel and donkey skeletons marked out the route. The poet Wang Wei, translated here by Stephen Owen, wrote a little verse to honor a friend who was leaving for these empty spaces. The poem ends: “I urge you now to finish / just one more cup of wine: / once you go west out Yang Pass, / there will be no old friends.” If a traveler falls asleep in this desert, Polo wrote, when he wakes, he will hear invisible spirits talking to him as if they were his companions. They may even call him by name. “I listened. I could hear nothing.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020