DUNHUANG

Dunhuang (on the Lanzhou-Urumqi train line, 750 kilometers northwest of Lanzhou and 750 kilometers southeast of Urumqi) is an oasis town of about 190,000 people and jumping off point for Mogao Caves. One of the premier Silk Road sites, it boasts a new airport, several four-star hotels a number of small hotels and guest houses.

In the Silk Road era Dunhuang was known as Shazhou — City of Sands. Today, it is one western China’s most cosmopolitan centers, as visitors come from all over the world to check out Mogao Caves. About 300,000 visitors, nearly all of them arriving in the hot summer, visit the town every year. Dunhuang means "Blazing Beacon."

Dunhuang is situated in a oasis containing Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan ("Singing-Sand Mountain"). It’s remote location in northwestern Gansu Province, far from any major city, belies how bustling it must have been when it was filled with Silk Road merchants, suppliers, and entrepreneurs. . The Chinese government make of point of criticizing late 19th century Western "archeologists," who explored Dunhuang and other Silk Road towns and made up off with some of the best art and sculptures, which are now displayed in foreign museums.

According to the International Dunhuang Project: “Dunhuang has a history of over two thousand years. Lying on the Dang River, which flows south and disappears into the Gobi desert, the town was established as a Chinese military garrison in the 2nd century B.C.. Defensive walls with watchtowers were built to its north. On the junction where the main Silk Road split into northern and southern branches around the Taklamakan desert to its west, Dunhuang grew and prospered. In the 4th century an itinerant monk excavated a meditation cave in a cliff face south-east of the town. Others followed and by the 8th century there were over a thousand cave temples. One cave was used as a library and filled with manuscripts and paintings. It was sealed and hidden in about AD 1000 and its discovery in 1900 revealed an unrivalled source for knowledge of the official and religious life in this ancient Silk Road town." [Source: International Dunhuang Project: Silk Road Exhibition idp.bl.uk]

Tourist Office: Dunhuang Tourism Bureau, 13 East Yangguang Rd, 736200 Dunhuang, Gansu, China, tel. (0)-94-732-2236, fax: (0)- 94-732-2234 Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Maps of Dunhuang: chinamaps.org ; Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Getting There: Dunhuang is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. Travel China Guide Travel China Guide

See Separate Articles: GANSU PROVINCE: LANZHOU AND NEARBY BUDDHIST AND TIBETAN SITES factsanddetails.com ; SILK ROAD SITES IN GANSU factsanddetails.com ; MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ; GOBI DESERT SIGHTS IN INNER MONGOLIA AND GANSU IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Dunhuang and the Silk Road

Dunhuang was a stop on the Silk Road and was visited by Marco Polo (See Above). It is situated at strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route between China, Central Asia and Europe as well as the main road between India, Lhasa, Mongolia and Southern Siberia. It sits at the controlling entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which led straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (Xi'an) and Luoyang. The ruins of a huge Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) watchtower made of rammed earth seen today Dunhuang is one illustration of the town’s economic — and military — importance.

The Silk Road started in Chang'an (Xian), about 1,700 kilometers from Duhuang and made its way to Europe via the Black Sea, Constantinople and the Mediterranean coast. In Dunhuang they could get fresh camels, food and guards for the journey around the dangerous Taklamakan Desert. Before departing Dunhuang some would pray to the Mogao Caves for a safe journey, if they came back alive they would thank the gods at the grottoes and perhaps donate money from some cave paintings. To cross the desert and frontiers they formed caravans for protection against brigands and bandits. The next stop on the way to Central Asia was, Kashi (Kashgar), over 2,000 kilometers to the west. At Kashi most would trade and return.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Whether taking the longer northern route or the more arduous southern passage, travelers converged on Dunhuang. Caravans came loaded with exotic goods redolent of distant lands. Their most important commodities, however, were ideas — artistic and religious. It's no wonder that the Mogao painters, illustrating the greatest of all Silk Road imports, infused their murals with an array of foreign elements, from pigments to metaphysics. Emerging from the wind-sculptured dunes some 12 miles southeast of Dunhuang is an arc of cliffs that drop more than a hundred feet to a riverbed lined with poplar trees. By the mid-seventh century, the mile-long rock face was honeycombed with hundreds of grottoes. It was here that pilgrims came to pray for safe passage across the dreaded Taklamakan Desert. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

Silk Road Route in China

The overland Silk Road route to the west began in Changan (Xian), the capital of China during the Han, Qin and Tang dynasties. It stopped in the towns of Zhangye, Jiayuguan, Langzhou, Yumen, Anxi and Nanhu before dividing in three main routes at Dunhuang.

The three main routes between Dunhuang and Central Asia were: 1) the northern route, which went through northwest China through the towns of Hami and Turpan to Central Asia: 2) the central route, which veered southwest from Turpan and passed through Kucha, Aksu and Kashgar; and 3) the southern route, which passed through the heart of the Taklamakan Desert via the oasis towns of Miran, Khotan and Yarkand before joining with the central route in Kashgar.

On the southern route through western China the going began getting difficult near present-day Lanzhou, where the "Gate of Demons," marked the approach to an area, which the writer Mildred Cable said featured "rushing rivers, cutting their way through sand...an unfathomable lake hidden among the dunes...sand-hills with a voice like thunder" and "water which could be clearly seen and yet was a deception."

The going started to get really rough around the Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang), traditionally regarded as the frontier of Chinese Turkestan and entrance to the vast and inhospitable Taklamakan Desert. where Cable wrote, the desert "is a howling wilderness, and the first thing which strikes the wayfarer is the dismalness of its uniform, black, pebble strewn surface." From here the Silk Road followed a line of oases to Kashgar or veered north into present-day Kazakhstan.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The routes around the Takla Makan desert in the Tarim Basin connected the Chinese capitals at Ch'ang-an (modern Xi'an) and Loyang with the western frontiers from the Han to Tang periods. The routes divided into northern, southern and central branches around the Tarim Basin at Dunhuang. The northern route started from the Jade Gate outside of Dunhuang and proceeded to the oasis of Turfan, near the Buddhist cave complex at Bezeklik. From Turfan, this route followed the southern foothills of the Tien-shan mountains to Karashahr and Shorchuk (near modern Korla) before reaching Kucha, an oasis surrounded by Buddhist cave complexes such as Kyzil and Kumtura. The northern route continued through Aksu, a junction for routes over the Tien-shan, and Maralbashi, near the Buddhist caves of Tumshuk, to Kashgar, where the southern route reconnects. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“The southern route began at the Yang-kuan gate outside of Dunhuang and continued to oases on the southern rim of the Takla Makan desert such as Miran, Charklik, Cherchen, Endere, and Niya. This route followed the northern base of the Kun-lun mountains to Khotan and Kashgar. An intermediate route from Dunhuang led to the military garrison at Lou-lan on Lop-nor Lake, where branches diverged to Miran on the southern route and Karashahr on the northern route. Travelers' itineraries around the Tarim Basin depended on their goals and destinations, the political and physical environment, and economic conditions. *\

Archeological Evidence of the Silk Road Trade in China

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Many artifacts demonstrate long-distance trade connections and cultural transmission between China, Khotan (Hotan in present-day Xinjiang, China) on the southern silk route, and the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent. Fragments of finely woven tabby silk from China reflect long-distance trade or tribute relations with Khotan during the third or early fourth centuries CE. Coins of Indo-Scythian (Saka) and Kushan rulers (see essays on Sakas and Kushans) and an incomplete manuscript of a Gandhari version of the Dharmapada were found near Khotan. Other items imported to Khotan from the northwestern Indian subcontinent included small Gandharan stone sculptures and moulded terracotta figures. Long-distance trade in highly valued Buddhist items (such as manuscripts, small sculptures, miniature stupas, and possibly relics) prefigured later connections between Buddhist communities in Khotan and Gilgit. Khotan was not only a regional commercial and religious center of the southwestern Tarim Basin, but also functioned as a connecting point between China, India, western Central Asia, and Iran. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“The Shan-shan kingdom, which flourished on the southern silk route between Niya and Lou-lan until the fourth century CE, benefited from long-distance trade between China and eastern Central Asia. In exchange for luxury items from these regions, Chinese silk was probably used in commercial transactions, since silk was preferred to copper coins as currency. The economic prosperity of agricultural oases and trading centers on the southern silk route enabled Buddhist communities to establish stupas and monasteries. As Marilyn Rhie observes in Early Buddhist Art of China & Central Asia (vol. 1, p. 429), Buddhist sculptures from Miran and Khotan display many similarities with the artistic traditions of Gandhara, Swat, and Kashmir in the northwestern Indian subcontinent. Mural paintings at Miran reflect ties with both the art of western Central Asia and northwest India (Rhie, p. 385). Administrative documents found at Niya, Endere, and Lou-lan written in the Gandhari language and Kharosthi script demonstrate linguistic and cultural ties between the southern silk route oases and the northwestern Indian subcontinent in the third to fourth centuries CE. *\

“Intermediate routes through Karashahr and northern routes through Turfan probably eclipsed the southern route by the fifth century CE (according to Rhie, p. 392). Many of the most important archaeological sites on the northern silk route are clustered around Kucha and the Turfan oasis. Mural paintings in cave monasteries, stupa architecture, artifacts, and other remains from approximately the third to seventh centuries at sites around Kucha show closer stylistic affinities with the northwestern Indian subcontinent, western Central Asia and Iran than with China. Sites located further east along the northern silk route belonging to relatively later dates in the seventh to tenth centuries typically reveal more Chinese and Turkish elements. Mural paintings from the cave monastery of Kyzil demonstrate continuities between the art of the western part of the northern silk routes and the artistic traditions of Swat, Gandhara and Sassanian Iran in the middle of the first millennium CE. Monks and merchants traveling on the northern and southern silk routes were responsible for maintaining commercial, religious, and cultural contacts between India, Central Asia, and China. *\

“Material remains from sites along the silk routes reflect close relations between long-distance trade and patterns of cultural and religious transmission. Demand for Chinese silk and luxury commodities which were high in value but low in volume stimulated commerce. Valuable items such as lapis lazuli, rubies, and other precious stones from the mountains of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Kashmir probably led travelers to venture into these difficult regions. Some of these products became popular items for Buddhist donations, as attested in Buddhist literary references to the "seven jewels" (saptaratna) and reliquary deposits (see Xinru Liu, Acient India and Ancient China, pp. 92-102). Long-distance trade in luxury commodities, which were linked with the transmission of Buddhism [see essay on Buddhism and Trade], led to increased cultural interaction between South Asia, Central Asia, and China. *\

Hexi Corridor

The heart of Gansu Province is the Hexi Corridor, a 1,000-kilometer-long narrow strip of land on the western bank of the Yellow River that provides access between the Central Plans of China to the west and was a key part of the Silk Road.

Hexi Corridor connects China with Central Asia runs along the "neck" of Gansu province. The Han dynasty extended the Great Wall across this corridor, building the strategic Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang) and Yangguan fort towns along it. Remains of the wall and the towns can be seen there. The Ming dynasty built the Jiayuguan outpost in Gansu. Nomadic tribes, including the Yuezhi and Wusun, lived to the west of Yumenguan and the Qilian Mountains at the northwestern end of Gansu and occasionally played into a part imperial Chinese geopolitics.

Hexi Corridor stretches from Lanzhou to the Jade Gate and is bound from north by the Gobi Desert and Qilian Mountains from the south. Dunhuang sits at the controlling entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which led straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (Xi'an) and Luoyang. The ruins of a huge Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) watchtower made of rammed earth seen today Zhangye Danxia (500 kilometers northwest of Lanzhou) is located in the middle of the Hexi Corridor in Zhangye city. Zhangye Danxia landforms features magnificent scenery with rocks of peculiar shapes and bright colors. It is arguably the best example an arid Danxia landscape.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “For more than 2,000 years, a branch of the Silk Road — the 600-mile-long Hexi Corridor — has angled southeast from the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts to the Yellow River loess plains. The Hexi is hemmed in by deserts to the north and west, and by the great Qilian mountain range to its south. It is about 10 miles wide at its narrowest point, with oasis towns every 50 to 100 miles. For most of the Han dynasty, which lasted roughly from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, no soldier, pilgrim, explorer or trader could enter northwestern China without first passing through the corridor, which was vigorously guarded. In A.D. 123, the imperial secretary Chen Zhong, in a strategic memo to the emperor, translated in 2009 by John E. Hill, wrote that if the Western Regions were not defended, “the wealth of the [nomadic Xiongnu tribes] will increase; their audacity and strength will be multiplied,” and the four garrisons along the Hexi Corridor would be endangered. “We will have to rescue them,” he continued. The great cities of China’s central plain, including the capital, would then be left vulnerable to attacks.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Yumen Pass (Jade Gate)

Yumenguan(Yumen Pass, 80 kilometers northwest of Dunhuang) is the name of a pass of the Great Wall also known as Jade Gate or Pass of the Jade Gate. During the Han dynasty (202 A.D. – A.D. 220), this was a pass through which the Silk Road and the main route to Central Asia passed. Just to the south was the Yangguan pass, which was also an important point on the Silk Road. [Source: Wikipedia]

Although the Chinese word guan is usually translated as "pass", it more specifically means "frontier pass". Yumen guan and Yang guan were the two most famous passes leading to the north and west from Chinese territory. During the Early Han, "a defensive line was established from Jiuquan ('Wine Springs') in the Gansu Corridor west to the Jade Gate Pass at its end." Yumenguan should not be confused with Yumen city 400 kilometers to the east. Yumenguan is called 'Jade Gate Frontier-post,' named because many jade caravans passed through it. The original Jade Gate was erected by Emperor Wudi around 121 B.C. and its ruins can still be seen today. Until the 6th century, it was the final outpost of Chinese territory for caravans on their long caravan journeys to India, Parthia, and the Roman Empire. [Coordinates 40°21 12.6"N 93°51 50.5"ECoordinates: 40°21 12.6"N 93°51 50.5"E]

Bonavia & Baumer wrote: “The remains of these two important Han-dynasty gates are about 68 kilometers (42 mi) apart, at either end of the Dunhuang extension of the Great Wall. Until the Tang dynasty, when the gates fell into disuse, all caravans travelling through Dunhuang were required to pass through one of these gates, then the westernmost passes of China. Yumenguan lies about 80 kilometers (50 mi) northwest of Dunhuang. It was originally called the 'Square City,' but because the great jade caravans from Khotan entered through its portals, it became known as the Jade Gate Pass. In the third and fourth centuries turmoil swept through Central Asia, disrupting overland trade, and the sea route via India began to supplant it. By the sixth century, as caravans favoured the northern route via Hami, the pass was abandoned. In 1907, Sir Aurel Stein found bamboo slips naming the site as Yumenguan, and in 1944 Chinese archaeologists discovered relics that confirmed this. With its 10-meter-high (32 foot) mud walls pierced by four gateways, the square enclosure covered more than 600 square meters (718 square yards) in the midst of unbounded desolation. Yanguan lies 75 kilometers (47 mi) southwest of Dunhuang but consists of only the ruins of a high beacon tower. [Source: Bonavia & Baumer (2004), pp. 176, 178. Quoted in Hill (2009), p. 138]

Sights in Dunhuang

Crescent Moon Lake (five kilometers southwest of Dunhuang) is an oasis body of water, not doubt a sight for sore eyes for Silk Road travelers, nomads and merchant. There is a small resort here. Activities includes camel and 4x4 rides.

Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Spring marks the beginning of the vast sand dune area of Dunhuang, The mingsha mountains extend for 40 kilometers from east to west and 20 kilometers fron north to south. The dunes are famous for the echoing sound produced by wind blowing the sand. Crescent Springs is a moon-shaped pond sided by sand dunes.

There is a modern reconstruction of a Ming-era temple complex that was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution in 1968. One can organize a camel ride through the dunes from here. Climbing the dunes at Mingsha Shan can be an adventure. There are impressive views of the dunes and the surrounding Taklamakan Desert. Hiking on the dunes takes a lot of effort.

Singing Sand Mountain gets its name from the pleasant sound the wind makes when it blows over the sand. Composed of sandstone ridges and sand dunes trapped by the ridges, Singing Sand Mountain extends 25 miles east to west and 12 miles north to south. "Singing Sand Dunes" sand storms are said to create almost melodic sounds as millions of minute particles of sand bounce and rub against one another. You're unlikely to hear them, as tours don't head for the dunes during sand storms! Adventure seekers can indulge in parasailing, tobogganing and sandboarding.

The Silk Route Museum is located in Jiuquan (200 kilometers from Dunhuang). The tomb of the Xiliang King is located here. Yumenguan (75 kilometers west of Dunhuang) is near a Han dynasty-era Silk Road gatehouse and near some impressive yardangs ( a streamlined protuberance carved from bedrock or any consolidated or semiconsolidated material by the dual action of wind abrasion by dust and sand, and deflation which is the removal of loose material by wind turbulence..

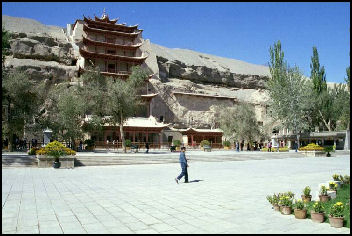

Mogao Caves

Mogao Caves (28 kilometers south of Dunhuang) — also known as Thousand Buddha Caves — is a massive group of caves filled with Buddhist statues and imagery that were first used in the A.D. 4th century. Carved into a cliff in the eastern foothills of the Mingsha Mountains (Singing Sand Mountains) and stretching for more than a mile, the grottoes are one of the largest treasure house of grotto art in China and the world.

All together there are 750 caves (492 with art work) on five levels, 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2,000 painted clay figures and five wooden structures. The grottoes contain Buddha and Bodhisattva statues and lovely paintings of paradise, asparas (angels), religious scenes and the patrons who commissioned the paintings. The oldest cave dates back to the 4th century. The largest cave is 130 feet high. It houses a 100-foot-tall Buddha statue installed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906) (A.D. 618-906). Many caves are so small they can only can accommodate a few people at a time. The smallest cave is only a foot high.

Mogao was designated a UNESCO World Heritage in 1987. According to UNESCO: “Situated at a strategic point along the Silk Route, at the crossroads of trade as well as religious, cultural and intellectual influences, the 492 cells and cave sanctuaries in Mogao are famous for their statues and wall paintings, spanning 1,000 years of Buddhist art.”

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Within the caves, the monochrome lifelessness of the desert gave way to an exuberance of color and movement. Thousands of Buddhas in every hue radiated across the grotto walls, their robes glinting with imported gold. Apsaras (heavenly nymphs) and celestial musicians floated across the ceilings in gauzy blue gowns of lapis lazuli, almost too delicate to have been painted by human hands. Alongside the airy depictions of nirvana were earthier details familiar to any Silk Road traveler: Central Asian merchants with long noses and floppy hats, wizened Indian monks in white robes, Chinese peasants working the land. In the oldest dated cave, from A.D. 538, are depictions of bandits bandits that had been captured, blinded, and ultimately converted to Buddhism. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes, with their paper-thin skin of painted brilliance, have survived the ravages of war and pillage, nature and neglect. Half buried in sand for centuries, this isolated sliver of conglomerate rock is now recognized as one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world. The caves, however, are more than a monument to faith. Their murals, sculptures, and scrolls also offer an unparalleled glimpse into the multicultural society that thrived for a thousand years along the once mighty corridor between East and West.

The Chinese call them Mogaoku, or "peerless caves." But no name can fully capture their beauty or immensity. Of the almost 800 caves chiseled into the cliff face, 492 are decorated with exquisite murals that cover nearly half a million square feet of wall space, some 40 times the expanse of the Sistine Chapel. The cave interiors are also adorned with more than 2,000 sculptures, some of them among the finest of their era. Until just over a century ago, when a succession of treasure hunters arrived across the desert, one long-hidden chamber contained tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts.

"The caves are a time capsule of the Silk Road," says Fan Jinshi, director of the Dunhuang Academy, which oversees research, conservation, and tourism at the site. A sprightly 71-year-old archaeologist, Fan has worked at the grottoes for 47 years, ever since she arrived in 1963 as a fresh graduate of Peking University. Most other Silk Road sites, Fan says, were devoured by the desert or destroyed by successive empires. But the Mogao caves endured largely intact, their kaleidoscope of murals capturing the early encounters of East and West. "The historical significance of Mogao cannot be exaggerated," Fan says. "Because of its geographical location at a transit point on the Silk Road, you can see the mingling of Chinese and foreign elements on nearly every grotto wall." UNESCO World Heritage Site Map: (click 1001wonders.org at the bottom): UNESCO Also try the UNESCO World Heritage Site Web site (click the site you want) World Heritage Site

See Separate Article MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Xuanquan Posthouse

Xuanquan Posthouse (50 kilometers east of Dunhuang) refers to the remains of an important courier station in the Hexi Corridor built in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. - A.D. 220) in the Gobi desert to the north of Huoyan Hill, which is an offshoot of Qilian mountains. A large number of Chinese documents written in bamboo and wooden slips from Han Dynasty were unearthed there, recording the postal system in the large transportation system of the Han Empire. These documents provided information on how transportation and communication was carried out along the Silk Roads. [Source: silkroad.org.cn]

The main function of the Xuanquan Posthouse to help relay a variety of mail, cummunications and information and provide lodging for passing messengers, officials, official personnel and foreign guests. The site of Xuanquan Posthouse covers an area of 22,500 square meters in which 4675 square meters have been excavated. The site contains complete architectural community remains of the Han Dynasty, including Wubao (fortress), stables, houses and auxiliary buildings outside the fortress and sites of beacon towers in the northwest corner of the Wei and Jin dynasties (3-4 century AD). Han Dynasty Post Road remainswere discovered 20 meters north of the north wall. The Wubao takes up a square area of 50 meters × 50 meters and faces east. On the northeast and the southwest corners of the square are turret ruins, surrounded by other architectural sites. The site of stables is located outside the south wall of the Wubao. More than 70,000 cultural relics have been excavated, mostly bamboo and wooden slips, silk manuscripts, paper-based documents, silk, calendars, stationery, lacquer ware, bronze ware, barley, alfalfa and other crops, as well as bones of horses, camels and other animals.

The slips document the passing horses and carts and the official settings, with descriptions of sealing, delivery and receipt of mails and records of diplomatic missions. Messengers from Asian territories such Uisin, Ferghana, Loulan, Khotan and Kucha in what is now western China and Central Asia and places further west such as Kapisa, Alexandra Prophthasia and Rouzhi, Qangly, Jiyue, and Junqi Phi Ogak. All this gives an idea of how extensive the Han Dynasty postal system and communications were. Xuanquan Posthouse faced the Shule River and Great Wall of the Han Dynasty and was connected with the Xuanquan Spring of Xuanquan Valley, showing how ancient posthouses relied on provision support from towns and rivers and how people of that time utilized nature to cross the Gobi desert.

Dunhuang Yardangs

Dunhuang Yardangs (southwest of Dunhuang) was nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2015. Yardangs are snake-like rock ridges created by scouring sand-laden winds. According to a report submitted to UNESCO: The “property presents the most majestic Yardang landscape in the arid and extremely arid desert regions in the temperate zone, including ridge-shaped Yardang landforms like a large fleet of ships in a vast sea, castle-shaped Yardang landforms of various shape combinations and isolated hill relic Yardang landforms with strange shapes and excellent aesthetic values, that contribute to the spectacular beauty of the desolate Gobi desert. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO, Coordinates:N40 23-40 34 E92 55-93 13]

The Yardangs in Dunhuang Yardang Geo-park with 251 square kilometers in area, are chartered with concentrated distribution and complex formation. They are composed by fluvio lacustrine silty clay with thin silt interlayer of middle-late pleistocene and alternately sculpted by wind and flood in a long time. Meanwhile, the Yardangs here has the best ornamental value than any other places, where all the respective Yardangs, including the ridge-shaped ones in adolescent period, the castle-shaped ones in adult stage, and isolated hill relics ones in late mature and old period can be visited. There are continuously distributed Yardangs that like grand fleets navigating over the ocean, and delicately sculptured Yardangs in peculiar shapes like sphinx, peacock and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. It was in this place that the term “Yardang” was nominated by Sven Hedin.”

“The nominated property possesses the most majestic Yardang landscape cluster in the arid and extremely arid desert regions in the temperate zone of the world. The ridge-shaped Yardangs are magnificent. Hundreds of ridge-shaped Yardang, each could be several kilometers long, stretch over several tens of kilometers, giving the impression of a large fleet group in a vast sea. The representation landscape “fleets” demonstrates the magnificent beauty of Gobi deserts.

“The castle-shaped Yardangs have various shapes and colors. Strata where sandstone and mudstone distribute in a staggered pattern form castles of various shapes, such as cubic hills, round hills, and temples shape, by the action of water and wind erosion. They are well-proportioned with ups and downs, preferably showing the desolation beauty of Gobi deserts. Isolated hill relics Yardangs have peculiar shapes. The most typical ones are towers, columns, beacon tower shapes and mushroom shapes, and animal shapes such as eagle, horse, monkey and turtle, as well as human-like figures such as warriors, old men, children and spirits. The representative Yardangs are "Sphinx", "Peacock" and "the Leaning Tower of Pisa", demonstrating the unique beauty of Gobi deserts.

Yardangs

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: “The internationally recognized geomorphic term “Yardang” was originated from Uygur language which means small hill with steep escarpments, and proposed by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin as a formal technical expression when he was exploring the Lop Nor region of Northwest China in the early 20th century. It represents the ridge-like, castle-like, or hill-like erosional landform with considerable scale in extremely arid region, or some basins in arid region, where the non-completely consolidated sediments were sculptured by the wind and flood. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO]

China owns the largest distribution of Yardangs with about 20,000 square kilometers in total area. The most representative Yardangs on earth are particularly concentrated in basins in Xinjiang and west of Gansu Province, as well as in the Qaidam Basin in Qinhai Province. These basins are located in the hinterland of the Eurasian continent under an extremely arid temperate continental climate.

The Basin at the middle and lower reaches of the Shule River and Lop Nor locates in the extremely arid triangle region of the Euroasian continent, one of the most arid regions in the world. The annual precipitation is lower than 50 millimeters. Climate here is with abundant wind and frequent sand/dust storm. The lithology of Yardang stratum are mudstone with fluvio lacustrine facies, siltstone, evaporate of neogene, middle-late pleistocene and the holocene with light brown, gray, white, khaki, and grey-green intercalary strata in some area. It includes Bulongji Yardang and Qiaowan Yardang in Guazhou County, Beihu Yardang and Dunhuang Yardang Geo-park in Dunhuang City, Loulan Yardang, Longcheng Yardang and Bailongdui Yardang in north and northeast Lop Nur basin.

Morphology, Camels and Geology of the Dunhuang Yardangs

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: The Dunhuang Yardangs “has various types of Yardangs that representing all the developing processes from the surface weathering, embryonic states, and mature states to disappearance. Furthermore, the nominated property is an outstanding example of wind-erosion, and complex wind and water erosion geomorphic processes in the arid and extremely arid desert regions in the temperate zone, reflecting the central Eurasia drying processes. It also contains important information for studying of the Tibetan Plateau uplift and central Eurasia drying processes.. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO]

“The nominated property has Yardangs with the most concentrated distribution, the largest scale and types, and the best preservation in the arid and extremely arid desert regions in the temperate zone in terms of geomorphic morphology Various types of Yardangs can be found in the nominated property, such as the Mesa, Sawback, etc. at an early development stage, as well as ridge-like shapes, whale back shapes and castle shapes, etc. at the peak stage, and isolated hill relics, pagoda forest shapes, cone-like shapes, etc. at the late stage, including the complete geomorphic types of Yardangs in the whole development process. Furthermore, the nominated property includes the three most representative shapes: ridges, castles, and isolated hill relics. All the landform features and diversities are unique in the world. Dunhuang Yardangs developed typical and magnificent geomorphic types acted mainly from wind erosion in the quaternary strata of lacustrine facies, and it is also the typical area with the most concentrated, the largest scaled and the best preserved Yardang landform.

The nominated property is an outstanding example of the environmental changes as well as the geologic and geomorphic processes in the arid and extremely arid desert regions in the temperate zone

“In the nominated property, the major external forces are weathering, wind erosion, flood, gravity collapse, etc. In particular, weathering and flood are active in the early stages, wind erosion is active in the middle stage and gravity collapse occurs in the late stage. The nominated property also presents the complete developing process of Yardang formation from surface weathering in the initial phase, the Yardang rudiment at the early stage, the massive landforms at maturity to disappearance at the end. The property presents the geologic processes of various geographical units, in different stratigraphic sequences, different development periods, and different types under various exogenic forces. It is an outstanding example of the on-going geologic and geomorphic process of Yardang’s generation and destruction, and is the ideal type of Yardang in the world from which the name of the landform was taken. Furthermore, Yardangs are mainly composed of fluvio lacustrine sandstone and mud stone formed in the Quaternary. The stratigraphic sequences constituting Yardang landforms recorded the ancient natural geological section under climate change, and contain important information for studying the Tibetan Plateau uplift and central Eurasia drying processes.

“The nominated property is an important habitat for world endangered wild bactrian camel (Camelus ferus Przewalski). Wild bactrian camel (Camelus ferus Przewalski) is more endangered than wild giant panda on the earth. Its world population is only about 730-880, 420-470 in China. The artiodactyla wild animals only live at Annanba in Aksai County north of Altun Mountains, Xihu in Dunhuang of Gansu province, Lop nur in Xinjiang province, and Inner Mongolia. The nominated property is an important hideout of wild bactrian camels, and the World Conservation Union has treated them as endangered species listed in the red book, and the convention on international trade has listed them as one of the first-class endangered species of the world. Wild bactrian camels have many special physiological functions that no other animals have. They are hungry, thirsty, heat-cold and aeolian sand resisting, and they are the only rare animals in the world which can drink salt water and eat salt plant for survival. They are intensively-distributed in this nominated property, and criss-cross Yardang landforms can provide hiding places for them.”

Traveling Between Dunhuang and Turpan by Road

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: ““I Left Dunhuang the next morning by taxi, heading for Turpan — 500 miles away. An hour into the journey, a distant city floated. I looked at the map, then out my window again, dazed. I wanted to follow the shining line of trees, to walk through the shimmering gateways, to climb those towers. ““Haishishenlou,” said the taxi driver, indifferent. He didn’t even glance out the side window but just looked at me in the rearview mirror. “Illusion.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“My map showed nothing to the east for several hundred miles. In his 1926 memoir “Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan,” translated two years later by Anna Barwell, the German archaeologist Albert von Le Coq wrote that the Uighurs called this phenomenon azytqa, “misleader,” adding that the mirage “is so lifelike that many inexperienced travelers may very easily follow it.” I would, too, if I had been driving. The nameless city looked far more alluring than the blank asphalt road. The vision traveled alongside the car, as if it were painted on the window glass. I knew, but did not want to believe, that it was unreal.

“Here, the Gobi changed from rosebud pink to black with rare streaks of ivory. The British-Hungarian explorer Marc Aurel Stein, in his 1920 piece for The Geographical Review titled “Explorations in the Lop Desert,” described the towerlike mesas near Dunhuang as quivering “phantom-like in the white haze,” and from a distance, the white bands among dark strata looked like mist rising over a river. But there was no water, just salt scattered along the dunes. In this region, Stein once wrote of “nature benumbed.”

“The British diplomat Eric Teichman pointed out in his 1937 “Journey to Turkistan” that those traveling in the caravans called this area the Four Dry Stages: This road was among the most ferocious, the most fatal relays not just in Central Asia but on the entire Silk Road network. Beyond, springs of bitter water were the only landmarks: Wild Horse Well, Clear Water, One Cup Spring, Muddy Spring, the Well of the Seven Horns.

“These stretches took weeks to cross even in the 20th century: From ancient times until the 1960s, camel and donkey skeletons marked out the route. The poet Wang Wei, translated here by Stephen Owen, wrote a little verse to honor a friend who was leaving for these empty spaces. The poem ends: “I urge you now to finish / just one more cup of wine: / once you go west out Yang Pass, / there will be no old friends.” If a traveler falls asleep in this desert, Polo wrote, when he wakes, he will hear invisible spirits talking to him as if they were his companions. They may even call him by name. “I listened. I could hear nothing.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020