MOGAO CAVES

Mural of Avolokitesvara

at Mogao Caves Mogao Caves (28 kilometers south of Dunhuang) — also known as Thousand Buddha Caves — is a massive group of caves filled with Buddhist statues and imagery that were first used in the A.D. 4th century. Carved into a cliff in the eastern foothills of the Mingsha Mountains (Singing Sand Mountains) and stretching for more than a mile, the grottoes are one of the largest treasure house of grotto art in China and the world.

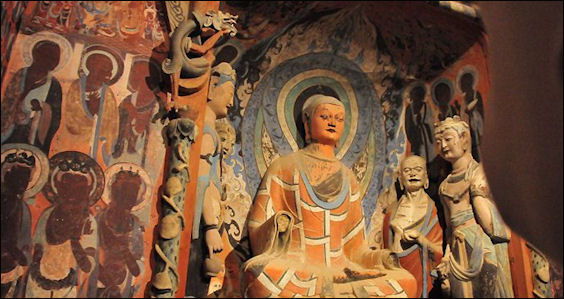

All together there are 750 caves (492 with art work) on five levels, 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2,000 painted clay figures and five wooden structures. The grottoes contain Buddha and Bodhisattva statues and lovely paintings of paradise, asparas (angels), religious scenes and the patrons who commissioned the paintings. The oldest cave dates back to the 4th century. The largest cave is 130 feet high. It houses a 100-foot-tall Buddha statue installed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906) (A.D. 618-906). Many caves are so small they can only can accommodate a few people at a time. The smallest cave is only a foot high.

Mogao was designated a UNESCO World Heritage in 1987. According to UNESCO: “Situated at a strategic point along the Silk Route, at the crossroads of trade as well as religious, cultural and intellectual influences, the 492 cells and cave sanctuaries in Mogao are famous for their statues and wall paintings, spanning 1,000 years of Buddhist art.”

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Within the caves, the monochrome lifelessness of the desert gave way to an exuberance of color and movement. Thousands of Buddhas in every hue radiated across the grotto walls, their robes glinting with imported gold. Apsaras (heavenly nymphs) and celestial musicians floated across the ceilings in gauzy blue gowns of lapis lazuli, almost too delicate to have been painted by human hands. Alongside the airy depictions of nirvana were earthier details familiar to any Silk Road traveler: Central Asian merchants with long noses and floppy hats, wizened Indian monks in white robes, Chinese peasants working the land. In the oldest dated cave, from A.D. 538, are depictions of bandits bandits that had been captured, blinded, and ultimately converted to Buddhism. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes, with their paper-thin skin of painted brilliance, have survived the ravages of war and pillage, nature and neglect. Half buried in sand for centuries, this isolated sliver of conglomerate rock is now recognized as one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world. The caves, however, are more than a monument to faith. Their murals, sculptures, and scrolls also offer an unparalleled glimpse into the multicultural society that thrived for a thousand years along the once mighty corridor between East and West.

The Chinese call them Mogaoku, or "peerless caves." But no name can fully capture their beauty or immensity. Of the almost 800 caves chiseled into the cliff face, 492 are decorated with exquisite murals that cover nearly half a million square feet of wall space, some 40 times the expanse of the Sistine Chapel. The cave interiors are also adorned with more than 2,000 sculptures, some of them among the finest of their era. Until just over a century ago, when a succession of treasure hunters arrived across the desert, one long-hidden chamber contained tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts.

"The caves are a time capsule of the Silk Road," says Fan Jinshi, director of the Dunhuang Academy, which oversees research, conservation, and tourism at the site. A sprightly 71-year-old archaeologist, Fan has worked at the grottoes for 47 years, ever since she arrived in 1963 as a fresh graduate of Peking University. Most other Silk Road sites, Fan says, were devoured by the desert or destroyed by successive empires. But the Mogao caves endured largely intact, their kaleidoscope of murals capturing the early encounters of East and West. "The historical significance of Mogao cannot be exaggerated," Fan says. "Because of its geographical location at a transit point on the Silk Road, you can see the mingling of Chinese and foreign elements on nearly every grotto wall." Websites: : UNESCO World Heritage Site site: UNESCO ; Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn

See Separate Articles: GANSU PROVINCE: LANZHOU AND NEARBY BUDDHIST AND TIBETAN SITES factsanddetails.com ; SILK ROAD SITES IN GANSU factsanddetails.com ; DUNHUANG: SAND DUNES, SILK ROAD SITES, YARDANGS AND MOGAO CAVES factsanddetails.com ; GOBI DESERT SIGHTS IN INNER MONGOLIA AND GANSU IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

History of Mogao Caves

Manjusri Debates

Vimalakirti at Mogao CavesMogao was a major center of Buddhist scholarship and a trading post on the Silk Road for more than a thousand years, until 1372 when the Chinese withdrew their garrisons and the area was taken over by the Mongols. The caves were largely abandoned after that. Originally there were a thousand grottoes, but now only 492 cave temples remain.

It is said the grottoes began when a monk (known by various names including Le Zun and Lo-tsun) came to Singing Sand Mountain, where he he had a vision and started to carve the first grotto. Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The caves began as a vision of light. One evening in A.D. 366, a wandering monk named Yuezun saw a thousand golden Buddhas blazing in a cliff. Inspired, he chiseled a small meditation cell into the rock; others quickly followed. The first caves were no larger than coffins. Soon, monastic communities began carving out larger caverns for public acts of devotion, adorning the shrines with images of the Buddha. It is these early grottoes that inspired the nickname the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

“Their canvases consisted of nothing more than river mud mixed with straw, but Dunhuang's artists would, over the centuries, record on these humble surfaces the evolution of Chinese art — and the transformation of Buddhism into a Chinese faith. One of Mogao's creative peaks came during the seventh and eighth centuries, when China projected both openness and power. The Silk Road was booming, Buddhism was flourishing, and Dunhuang was paying fealty to the Chinese capital. The Tang cave painters displayed a fully confident Chinese style, covering whole walls with minutely detailed Buddhist narratives whose color, movement, and naturalism made the imaginative landscape come alive. The Middle Kingdom would later turn inward, finally shutting itself off from the world during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in the 14th century.

"Unlike Indian Buddhists, the Chinese wanted to know in detail all the forms of the afterlife," says Zhao Shengliang, an art historian at the Dunhuang Academy. "The purpose of all this color and movement was to show pilgrims the beauty of the Pure Land — and to convince them that it was real. The painters made it feel like the whole universe was moving."

“More earthly tumult periodically swept through Dunhuang. Yet even as the town was conquered by competing dynasties, local aristocracies, and foreign powers — Tibet ruled here from 781 to 847 — the creative enterprise at Mogao continued without pause. What accounts for its persistence? It may have been more than a simple respect for beauty or Buddhism. Rather than wiping out all traces of their predecessors, successive rulers financed new caves, each more magnificent than the last — and emblazoned them with their own pious images. The rows of wealthy patrons depicted on the bases of most murals increased in size over the centuries until they dwarfed the religious figures in the paintings. The showiest patron of all may have been Empress Wu Zetian, whose desire for divine projection — and protection — led her to oversee, in 695, the creation of the complex's largest statue, a 116-foot-tall seated Buddha.

“By the late tenth century the Silk Road had begun to fade. More caves would be dug and decorated, including one with sexually charged tantric murals that was built in 1267 under the Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan. But as new sea routes opened and faster ships were built, land caravans slipped into obsolescence. China, moreover, lost control over large portions of the Silk Road, and Islam had started its long migration over the mountains from Central Asia. By the early 11th century several of the so-called western regions (part of modern-day Xinjiang, in China's far west) had been converted to Islam, and Buddhist monks placed tens of thousands of manuscripts and paintings in a small side chamber adjoining a larger Mogao grotto. Were the monks hiding documents for fear of an eventual Muslim invasion? Nobody knows for sure. The only certainty is that the chamber — now known as Cave 17, or the Library Cave — was sealed up, plastered over,and concealed by murals. The secret cache would remain entombed for 900 years.

Art and Sculptures in Mogao Caves

Over a period of about 700 years, from the 4th to the 11th century AD, Buddhist monks-often supported by rich patrons-excavated and executed astonishing works of art in Mogao caves. The arrival of Islam and the Mongols in the 12th century ended the cave creations and their virtual abandonment. The closure of the Silk Road and abandonment of the communities and towns along its lengths actually helped secure their preservation until they were "discovered" in 1907.

There are 735 caves of various shapes of which 492 are cave temples with art and sculptures. They contain 45,000 square meters of murals and 2,400 painted sculptures created during the Northern Liang ( A.D. 397-439), Northern Wei (386-534), Western Wei (535-556), Northern Zhou (557-581)., Sui (581–618), Tang (618–906), Five Dynasties (907–960), Song (960-1279), Western Xia (1038-1227) and Yuan (1279–1368) Dynasties. Most were created by the Five Dynasties period. By that time they had run out of room on the cliff and could not build any more grottoes. In 1900, over 50,000 items, including ancient manuscripts and painting from the Western Jin and Song Dynasties were found in Library Cave.

According to UNESCO: “Carved into the cliffs above the Dachuan River, the Mogao Caves southeast of the Dunhuang oasis, Gansu Province, comprise the largest, most richly endowed, and longest used treasure house of Buddhist art in the world. It was first constructed in 366AD and represents the great achievement of Buddhist art from the 4th to the 14th century. 492 caves are presently preserved, housing about 45,000 square meters of murals and more than 2,000 painted sculptures. [Source: UNESCO]

The Thousand-Buddha Caves constitute an outstanding example of a Buddhist rock art sanctuary.” The site “encompass caves, wall paintings, painted sculptures, ancient architecture, movable cultural relics and their settings...The group of caves at Mogao represents a unique artistic achievement both by the organization of space into 492 caves built on five levels and by the production of more than 2,000 painted sculptures, and approximately 45,000 square meters of murals, among which are many masterpieces of Chinese art.

“The unique artistic style of Dunhuang art is not only the amalgamation of Han Chinese artistic tradition and styles assimilated from ancient Indian and Gandharan customs, but also an integration of the arts of the Turks, ancient Tibetans and other Chinese ethnic minorities. Many of these masterpieces are creations of an unparalleled aesthetic talent.”

Historical Value of Mogao Cave Art

Outside Mogao Caves

According to UNESCO: Cave 302 of the Sui Dynasty (581–618) contains one of the oldest and most vivid scenes of cultural exchanges along the Silk Road, depicting a camel pulling a cart typical of trade missions of that period. Caves 23 and 156 of the Tang Dynasty (618-906) show workers in the fields and a line of warriors respectively and in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Cave 61, the celebrated landscape of Mount Wutai is an early example of artistic Chinese cartography, where nothing has been left out — mountains, rivers, cities, temples, roads and caravans are all depicted. [Source: UNESCO]

“Documents of Western Xia, Central Asian and Phags-pa scripts had been discovered through archaeological investigations in the 243 caves in the northern area of Mogao Caves, which was the area for monks to live and meditate and also served as the graveyard in the past.... As evidence of the evolution of Buddhist art in the northwest region of China, the Mogao Caves are of unmatched historical value. These works provide an abundance of vivid materials depicting various aspects of medieval politics, economics, culture, arts, religion, ethnic relations, and daily dress in western China. The discovery of the Library Cave at the Mogao Caves in 1990, together with the tens of thousands of manuscripts and relics it contained, has been acclaimed as the world’s greatest discovery of ancient Oriental culture. This significant heritage provides invaluable reference for studying the complex history of ancient China and Central Asia.

“For 1,000 years, from the period of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) to the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty(1276-1386), the caves of Mogao played a decisive role in artistic exchanges between China, Central Asia and India. The paintings at Mogao bear exceptional witness to the civilizations of ancient China during the Sui, Tang and Song dynasties.

The caves are strongly linked to the history of transcontinental relations and of the spread of Buddhism throughout Asia. For centuries the Dunhuang oasis, near which the two branches of the Silk Road forked, enjoyed the privilege of being a relay station where not only merchandise was traded, but ideas as well, exemplified by the Chinese, Tibetan, Sogdian, Khotan, Uighur and even Hebrew manuscripts found within the caves.

Discovery and Looting of Mogao Caves

Mogao Caves were occupied by Buddhist monks from the end of the 19th century up to 1930. In 1900, the priest Wang Yuanku discovered the famous Hidden Library, a trove of 50,000 documents, including the Diamond Sutra, the world's oldest book. In 1907, the British-Hungarian archeologist Sir Aurel Stein paid Wang four silver pieces and hauled off thousands of manuscripts, silk scroll paintings and wood slips, and the Diamond Sutra out of China. These are now housed in the British Museum, the British Library and the National Museum in New Delhi.

Mogao Cave 249

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “By the turn of the 20th century, when a Taoist priest named Wang Yuanlu became the sanctuaries' self-appointed guardian, many of the abandoned grottoes were buried in sand. In June 1900, as workers cleared away a dune, Wang found a hidden door that led to a small cave crammed with thousands of scrolls. He gave some of them to local officials, hoping to elicit a donation. All he received was an order to seal up the contents of the cave. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

It would take another encounter with the West to reveal the secrets of the caves — and to sound China's patriotic alarms. Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-born scholar working for the British government in India and the British Museum, made it to Dunhuang in early 1907 using Xuanzang's seventh-century descriptions to guide him across the Taklamakan Desert. Wang refused to let the foreigner see the bundles from the Library Cave — until he heard that Stein too was a keen admirer of Xuanzang. Many of the manuscripts, it turned out, were Xuanzang's translations of the Buddhist sutras that he had brought from India.

After days of wheedling Wang and nights of removing scrolls from the cave, Stein left Dunhuang with 24 cases of manuscripts and five more filled with paintings and relics. It was one of the richest hauls in the history of archaeology — all acquired for a donation of just 130 pounds sterling. For his efforts, Stein would be knighted in England, and for-ever vilified in China.

Stein's cache revealed a multicultural world more vibrant than anyone had imagined. Nearly a dozen languages appeared in the texts, including Sanskrit, Turkic, Tibetan, and even Judeo-Persian, along with Chinese. The used paper on which many sutras had been copied offered startling glimpses into daily life along the Silk Road: a contract for trading slaves, a report on child kidnapping, even a Miss Manners-style apology for drunken behavior. One of the most precious objects was the Diamond Sutra, a 16-foot-long scroll that had been printed from woodblocks in 868, nearly six centuries before Gutenberg's Bible.

Others — French, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese — quickly followed in Stein's path. Then in 1924 came American art historian Langdon Warner, an adventurer who might have served as inspiration for the fictional Indiana Jones. Enthralled by the beauty of the caves — "There was nothing to do but to gasp," he later wrote — Warner nevertheless contributed to their destruction, hacking out a dozen mural fragments and removing an exquisite Tang-era sculpture of a kneeling bodhisattva from Cave 328. The art is still in the careful custody of the Harvard Art Museum. But the defaced murals —and the empty space where the sculpture once knelt — are heartrending all the same.

Some Chinese officials, echoing their counterparts in Egypt and Greece, have called for the Mogao artifacts to be returned. Even the Dunhuang Academy's otherwise dispassionate book on the grottoes has a chapter titled "The Despicable Treasure Hunters." Foreign curators, meanwhile, contend that their museums have saved treasures that might otherwise have been lost forever — destroyed in the wars and revolutions of 20th-century China. Whatever one's views on the issue, there is an inescapable fact: The scattering of Mogao artifacts to museums on three continents has given rise to a new field of study, Dunhuangology, and today scholars around the world are working to preserve the treasures of the Silk Road.

A total of 243 caves have been excavated by archaeologists, who have unearthed monk's living quarters, meditation cells, burial chambers, silver coins, wooden printing blocker written in the Uighar and copies Psalms of written in the Syriac language, herbal pharmacopoeias, calendars, medical treatises, folk songs, real estate deals, Taoist tracts, Buddhist sutras, historical records and documents written in dead languages such as Tangut, Tokharian, Runic and Turkic.

Visiting Mogao Caves

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “According to legend, a fourth-century monk called Le Zun carved out the first cave by hand. Le Zun had planned to travel to India but stayed after he saw a vision of dazzling light, brighter than 10,000 suns, shining over the land. When I arrived at Mogao the next morning, the day was bright and cool; the leaves of ancient poplars and willow trees were just changing color, their golds reflected in the shallow waters of the Dachuan River. [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“For almost a thousand years, artists added new caves until the cliff face was honeycombed with painted corridors and recesses. Some caves are niches, while others can hold more than 50 people. Patrons commissioned caves as acts of piety, and the art reflected the hopes of those living in or passing through Dunhuang — to cross the desert safely, or to be reborn in paradise. Other caves might have helped the devout to meditate. Open to the sun and the winds as late as the 1940s, they are now protected behind metal doors and preserved in climate-controlled environments. Gansu is a province remote from any great city, and its landscapes — green mountains, eroded karst cliffs, empty deserts — amplified the ancient artwork. Left in their original settings, Buddhas and flying apsaras, demons and monsters, are still numinous.

“Nothing prepares a traveler for the frescoes. No book, no photograph, can ever capture the color-saturated details, or the strangeness, of the art there. Visiting the Mogao Caves was an intensely sensual experience: Painted dancers’ shadows moved, floating instruments made sound, incense billowed from the walls. The ninth-century Japanese monk Ennin, in a diary of his travels through the Tang empire, translated by Edwin Reischauer in 1955, remarked on the three-dimensional, illusionistic effect of one sacred painting: “We looked at [the image] for quite a while and it looked just as if it were moving.” The Qing dynasty writer Pu Songling (1640-1715), in his book “Strange Tales From a Chinese Studio,” translated by John Minford in 2006, described a visitor to a Beijing monastery who went even further: He entered a painting and had a brief love affair with one of its flying apsaras. “He was wafted bodily up onto the wall and into the mural itself. He felt himself pillowed on clouds, and saw stretching before him a grand panorama of palaces and pavilions,” wrote Pu. The man’s senses were “suffused with the heady perfume that emanated from her body, a scent of orchid mingling with musk.”

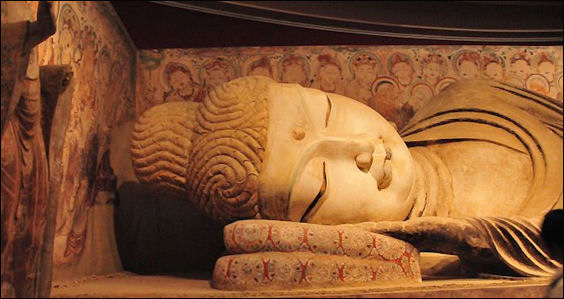

“Mogao’s artists, most of whom were anonymous, painted not just Buddhist paradises but riots and the fall of cities. All life is depicted here, from the movement of stars to competitions between philosophers; wedding scenes, slaughterhouses, wandering storytellers. Markets, brawls, women putting on makeup. Magicians, hunters chasing animals. A house burning down, swimmers splashing through the sea. I went from cave to cave, intent on remembering every line, every color. In the last cave, I saw a recumbent Buddha, half asleep; the statue’s eyes were full of sand.”

Mogao Cave 275

Mogao Cave 275 (Northern Liang A.D. 421-439)

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: Mogao Cave 275 “is one of the oldest caves in Mogao and has survived for more than 1,500 years. Although this cave is tiny, it has a relatively large statue in front of the main (west) wall; nevertheless, the proportions are harmonious. This main statue, 3.4 meters tall, is the largest of the early period. It is a Bodhisattva identified as Maitreya, the future Buddha. He has a round face, a robust physique and a calm expression. The handsome face has very long ear loops, straight nose, contoured lips and lightly protruding eyes, which are looking down compassionately on the visitor. Wearing a crown containing three round jewels (with a Buddha in the centre jewel), he sits cross-ankled. His sitting pose and decoration, as well as the triangular brocade-patterned backrest, suggest influences from Central Asia. [Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 27, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

“Statues of Maitreya are dressed either as a Bodhisattva (i.e., in the form of a nobleman, since the historical Buddha Sakyamuni was born a prince) or as a Buddha (in the form of a monk). The worship to Maitreya in China reached its zenith between the 5th and the 6th centuries, especially in the north. The cross-ankled sitting pose is the most popular among his statues of that time. The pair of lions flanking him do not appear convincing since the artists (mostly from central China) had not seen a real one and depicted them according to others’ descriptions and their own imaginations. ^*^

“On the upper part of both the north and south walls are three niches. The inner two on each wall are carved in the traditional Chinese building style — each has a gateway with a central tiled roof flanked by towers (known as que in Chinese). Inside each niche is a Bodhisattva seated cross-ankled. Que were popular until the Han dynasty (the 3rd century) for palaces and royal tombs, but few examples are found now. They are moulded and painted with details in Mogaoku. It contains very precious information on the history of Chinese architecture. ^*^

“In the third niche (not shown in the figure) on both walls near the entrance is a Bodhisattva in a pensive pose. These two niches are decorated in Indian style, with spreading branches of two trees on its arched top. Since the original front wall had collapsed, in the Northern Song (960-1127) a partition wall was built to provide some protection, and a new layer of mural was painted on the ceiling and part of the walls. This partition wall was removed in the 1990s, revealing the original layer. Another part of the mural was also damaged by the construction of a hole in the Qing (1638-1911) used for the convenience of walking to the adjacent cave. The hole is now filled. ^*^

Mogao Cave 275

Murals in Mogao Cave 275

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: “Murals in this cave illustrate the Buddhist stories. Each of them consists of several episodes within a single rectangular space, with multiple depictions of the same person to represent different times and places within the same scene. The dominant figures in all scenes are always larger in scale. All the figures are dressed and decorated in Central Asian style. The imported Indian colour shading technique (yun-ran) was employed, but the red or reddish brown has oxidized and turned to dark grey, and the white highlight has become off-white on the human faces. [Source: Dunhuang Research Academy,March 27, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

“Generally in the Buddha's Life Story, there should be Four Encounters (Prince Siddhartha encounters an old man, a sick person, a corpse and a mendicant monk). Here, on the south wall, only the first and the last were depicted to imply them all. From the first three, the young prince is aware that life is impermanent so it causes suffering, while the fourth sets out a path for liberation. ^*^

“Of the five jataka tales depicted on the north wall, the most famous are that of King Sivi (who offers his flesh — his whole body — as ransom to save a dove's live from a hawk) and King Candraprabha (who even gives away his head a thousand times in his thousand lives). The third king can tolerate his body to be used for lighting a thousand lamps; the fourth has a thousand nails nailed into his body, and the fifth gives away his eyes. These tales all signify self-sacrifice — especially of the physical self. The subject of these murals illustrates the message that achieving enlightenment requires toleration of pain and the sacrifices of self. Some scholars suggest the composition of this cave depicts Buddhahood in the past (with jataka on the north wall), the present (with Sakyamuni's life story on the south) and the future (with Maitreya in the centre). ^*^

“Below the jataka tales on the north walls is a row of 33 donor images. These men, 18 cm high, are clad in nomadic riding dress. All of them are shown in three-quarter view, lining up behind one another and facing in the direction of the procession. They hold a softly bent flower in their raised hand. A monk, who is taller than the others by a head, leads with an incense burner. There is no inscription to reveal information about these donors’ names and their ranking. According to their costumes, some suggest they belong to the Xianbei tribe who were active patrons at the time. Later in 439, Toba clan of the tribe founded the Northern Wei dynasty." ^*^

Mogao Cave 254

Mogao Cave 254 (Northern Wei A.D. 439-534)

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: Mogao Cave 254 “This cave is one of the most fabulous constructed in the fifth century. It has a square central pillar with niches on each side and a flat ceiling with painted coffering. The front portion of the cave has a gable ceiling with bas-relief simulated rafts in red. This design combines Chinese and Central Asian architectural features. The design, with a pillar in the centre, functions as a stupa for worship or walking meditation, and is a feature from India; the gable ceiling, as well as the style of four small niches above the murals in the front part of the cave, is typically Chinese. There is also a window of Chinese style above the entrance on the east wall, which is quite rare in Dunhuang caves. Sun shines through the window onto the main Buddha creating a halo on his head and upper torso, which seems to emphasize his stateliness."Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 26, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

“Entering this cave, one is attracted by the calm azure colour. On the front (east) face of the pillar is a niche in which sits the cross-ankled Buddha. The beautiful blue of his halo and mandorla is made of lapis, which was imported from present-day Afghanistan, and was as precious as gold at that time. Some scholars suggest that this statue illustrates the episode in which Maitreya descends to Earth in the future, while the small figures in Bodhisattva's form in the niches on the side walls represent him meditating in Tushita Heaven now. On the other hand, some insist that this is the statue of Sakyamuni, and that the Bodhisattvas in the small niches should not be Maitreya since it is not logical to repeat the same theme in a row along the walls. ^*^

“Behind the pillar on the west wall is a Buddha dressed in a white robe, which is quite unusual. Many interesting suggestions have been put forward to explain why his robe is white. Recently, the paints in this cave were analyzed by the Dunhuang Academy. Arsenic was found, suggesting the original colour of this robe could have been beige or light yellow. The remaining area of the wall is painted with the Thousand-Buddha motif. These Buddhas are in the same foreign style as that of the jataka; however, each of them (1,235 in total) was inscribed with Chinese names. These miniature images represent Buddhas from the past and future kalpa (literally: aeon). Together with the statues and paintings of Sakyamuni and Maitreya, both belong to the present kalpa. The arrangement of this cave focuses on the Buddhas in all times. ^*^

“In Buddhist tradition, the replication of the image of the Buddha is a valid method of spreading Buddhism and of attaining merit for oneself. Also, visualizing Buddha is one of the key methods of meditation. Therefore, the Thousand-Buddha motif has always been popular. At the top of all walls is a frieze depicting a heavenly scene. Each of the musicians plays a different instrument, and dancers in various poses perform under an arched opening. It illustrates the bliss of heaven. ^*^

Mogao Cave 254

Murals in Mogao Cave 254

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: Mogao Cave 254 ““The murals of this cave are very significant. They are mostly depictions of the jataka, previous life stories of the Buddha. Their unique and painstaking compositions convey a sense of firmness and resolve, attracting numerous artists. The Mahasattva jataka on the south wall illustrates Prince Sattva offering himself to a starving tigress and her cubs. The scene consists of several episodes within a single rectangular space. It starts from the top centre (1) with Prince Sattva and his two brothers looking down at the tigress and her seven cubs. The story continues on the right. (2) The prince kneels and pierces his neck with a bamboo stick, and (3) then dives with an outstretched left arm from the cliff to feed the tigress. The figures of the Prince touch each other to form a beautiful curve. (4) Then his remains are found by his saddened family. A Chinese style stupa built to commemorate the event concludes the story. The stupa was depicted in a very unusual way. The three storey building is shown in a bird's eye view but its front steps are at ground level, refocusing the attention on the main theme. This story is depicted in a circular sequence. It is a sad episode but not meant to be frightening and no gore is depicted. [Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 26, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

“There are more principal scenes, including Buddha's Enlightenment (the Subjugation of Mara), on the same wall. Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha's lay name), is meditating under a fir tree. When he is about to attain enlightenment, Mara (king of demons) and his soldiers attack him with all sorts of weapons and poisoned arrows, but everything fall before reaching him. Mara's three beautiful daughters (left bottom corner) seduce him but turn into old and ugly women (right bottom corner) right away. All these attacks serve as a foil for the Buddha. He subjugates Mara, who personifies all kinds of temptation and vexation, and attains enlightenment. His right hand is in an ‘earth touching’ mudra which means he is calling upon the earth to be his witness of becoming a Buddha (an enlightened one). Indian fir tree has been renamed to Bodhi (enlighten) tree thereafter. As a protagonist, Buddha's outsized figure is at the centre. The artists demonstrated outstanding achievement by creating a sharp contrast between the Buddha who is dignified, calm and full of compassion, and the demons who look wrathful, cruel and aggressive. ^*^

“On the north wall are scenes of the preaching Buddha, together with Nanda (his younger brother) Entering Monastic Life, and King Sivi jataka. The King Sivi jataka panel illustrates one of the most popular themes in the early caves. In it, the king offers his flesh, including his whole body, to save a dove's live from a hawk. The outsized figure of the king sits in a lalita pose, turns to one side in a three-quarter view, and is flanked by rows of figures in the assembly. On his right, each of the sad-looking court ladies has a different appearance. One of them is embracing the king's knee and begging him not to cut his flesh. The artists skillfully narrated the rich content in a single picture. The costumes of figures and the painting style of the murals in this cave are strongly influenced by the art of Central Asia." ^*^

Mogao Cave 249 (Western Wei A.D. 534-556)

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: “This cave has a truncated pyramidal ceiling with zaojing, which was a new fashion in the Western Wei, following the earlier prevailing central-pillared style. This kind of roof provides a broader view of the cave and more freedom for the motif arrangement. All the images in this cave were painted in contemporary ideal standard — tall and slim, and demure and feminine, in order to look like Chinese immortals. They are floating on clouds with long flying scarves, as if the cave was really breezy and expressing the scene of heaven. Around the zaojing, on the four slopes, are Buddhist images, which are accompanied by immortals and gods from Hindu and Chinese mythology. This design is very similar to that of Cave 285. “[Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 23, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

“On the west slope, the four-eyed and four-armed giant at the centre is King of asura, which is one of the six categories of sentient beings in samsara (the endless circle of birth and death). He is holding the sun and the moon, and standing on the ocean with his legs partially submerged to below the knees. Above him are Mount Sumeru (the cosmic mountain) and the Heaven Gate. Beside him are gods of Wind (the one holding a billowing bag, to the left of the King's raised arms), Rain (below the Wind God and close to the edge of the slope), Thunder (the one playing a circle of drums, to the right of the King's raised arms) and Lightning (the one holding a drill or vajra, below the Thunder God and close to the edge of the slope). These gods are all animal-headed. ^*^

“On the east slope are two wrestlers holding the Mani pearl, a wish-fulfilling jewel and a metaphor for Buddha's wisdom. A small difference from Cave 285 is that the two serpent-tailed Fuxi and Nuwa (the first ancestors in Chinese mythology) flying towards the pearl are not depicted here. On the north side, two of the four Chinese mythological protectors, Scarlet Bird (of the south) and Snake-turtle (of the north) are next to one of the wrestlers. Also on the slope are heavenly beings (Wu-huo) with two horns and two wings; and the three mythological creatures (Kai-ming) with 13, 11 or 9 human heads on tiger bodies, who might be the gods of Heaven, Earth and Humans, respectively. ^*^

Mogao Cave 249

“The north and south slopes depict two immortals traveling in heaven and escorted by a procession. The one on the south slope, riding in a four-phoenix chariot, is identified as the Western Mother Queen who existed a long time ago in Chinese mythology. The one on the north slope, riding in a four-dragon chariot, is the Eastern King who appears much later than the Queen. Originally they were described as half-human and half-beast creatures, and then humanized as royalty. According to legend, they meet once a year, but are not clearly described as husband and wife. They are in charge of everything in heaven and earth. If one can see them, it means one has attained immortality. The popularity of their images began in the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD).

“Some scholars have different opinions on the identification of many images in this cave. Some suggest these two figures are Indra and his consort. Indra is an important god in Hinduism, but assimilated into Buddhism as a chief in one of the many heavens. According to Buddhism, god (deva) and goddess (devi) are considered as a kind of sentient beings within samsara. At the bottom of the slopes are landscape and hunting scenes. In the hunting scene, a hunter on a galloping horse is turning back to shoot. This posture is known as the Parthian shot since it was a military tactic made famous by the Parthians, ancient Iranian people. The Parthian cavalrymen usually shot the enemy while retreating or pretending to retreat. This scene was prevalent in Persian art of the time, while the plain mastery outline technique for the images of boars and ox was typically Chinese. Around the top of the walls are musicians performing in heaven's balcony. Each is in an open cell facing outward, as if they are on stage. One is energetically blowing a conch, as another is calmly playing a lute. Their darker skin, the costumes and poses indicate that they are from Central Asia or India. The thick bold outline is a simple but distinct characteristic. ^*^

Mogao Cave 148 (Tang, A.D. 705-781)

According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: “This cave has a transverse rectangular layout (17x7.9m) and a vaulted roof. The interior looks like a big coffin because its main theme is the Buddha's nirvana (his demise; the liberation from existence). Because of the special shape of this cave, it has no trapezoidal top. The Thousand-Buddha motif is painted on the flat and rectangular ceiling. This motif is original, yet the colours are still as bright as new. On the long altar in front of the west wall is a giant reclining Buddha made of stucco on a sandstone frame. It is 14.4m long, signifying the Mahaparinirvana (the great completed nirvana). More than 72 stucco statues of his followers, restored in the Qing, surround him in mourning. [Source: Dunhuang Research Academy, March 6, 2014 public.dha.ac.cn ^*^]

Mogao Cave contains “the largest and best painting about Nirvana in Dunhuang...The Buddha is lying on his right, which is one of the standard sleeping poses of a monk or nun. His right arm is under his head and above the pillow (his folded robe). This statue was later repaired, but the ridged folds of his robe still retain the traits of High Tang art. There is a niche in each of the north and south walls, although the original statues inside were lost. The present ones were moved from somewhere else. ^*^

“On the west wall, behind the altar, is the beautifully untouched jingbian, illustrations of narratives from the Nirvana Sutra. The scenes are painted from south to north, and occupy the south, west and north walls with a total area of 2.5x23m. The complete painting consists of ten sections and 66 scenes with inscriptions in each; it includes more than 500 images of humans and animals. The inscriptions explaining the scenes are still legible. The writings in ink read from top to bottom and from left to right, which is unconventional. However, the inscription written in the Qing dynasty on the city wall in one of the scenes is written from top to bottom and from right to left, the same as conventional Chinese writing. Both of these writing styles are popular in Dunhuang. ^*^

“In the seventh section, the funeral procession is leaving town on the way to Buddha's cremation. The casket in the hearse, the stupa and other offerings, which are carried by several dharma protectors in front, are elaborately decorated. The procession, including Bodhisattvas, priests and kings carrying banners and offerings, is solemn and grand. ^*^

removing teeth from Cave 148

“In the ninth section, Indra (one of the gods) is depicted in two continuing scenes. In the first, he stands beside the casket and is removing Buddha's teeth. In the next, he travels on a cloud to bring the teeth back to heaven to be worshipped (top-left). On the other side (top-right), two asuras (a kind of celestial being) are escaping on a cloud after stealing two of the Buddha's teeth. The contents of the painting are substantial and the depictions are very detailed and magnificent. The architecture and costumes in this mural are of Chinese style. Interestingly, a rooster is on top of the casket, which is a typical Chinese funeral custom for dispelling evil spirits. ^*^

“In Dunhuang, mural content with Vajrayana (the last phase of Indian Buddhism) first appears in the Sui caves. Vajrayana flourished in High Tang, thus it is called the Tang-mi (literally, the Vajrayana in the Tang dynasty). In this cave were the earliest examples of Vajrayana art in Dunhuang. It includes jingbian on the thousand-armed and thousand-eyed Guan-yin (Avalokitesvara) on the east wall above the entrance, and statues of his other forms — Amoghapasa in the north niche and Cintamanichakra in the south niche. Although the two original statues are now missing (the present ones were made in the Qing), the content of this cave is recorded on a stele, built in 776 or earlier, in the antechamber. Also in the antechamber are two devaraja (Heavenly Kings), two vajrapani (dharma protectors) and two lions made in Middle Tang and restored in the Qing. ^*^

“On the east wall, at each side of the entrance, other jingbian are painted — Amitabha is on the south side while the Medicine Buddha is on the north. Both of them have vertical margins on both sides to provide additional information on the sutra. They were painted in the High Tang and partly altered in the Western Xia. The magnificent depictions still represent Tang art. The main halls, corner buildings, cloisters, pavilions on water, etc. provide very good information on Tang architecture. In the corridor is the illustration of the Sutra of Requiting Blessing Received, which emphasizes filial piety and is believed to be written by the Chinese to conform with Confucius’ teachings. This is the first time the sutra is illustrated in Dunhuang." ^*^

Mogao Cave 302 (Sui Dynasty, 581–618)

Cave 302 of the Sui Dynasty (581–618) contains one of the oldest and most illustrative scenes of cultural exchanges along the Silk Road. It shows a camel pulling a cart typical of trade missions of that time as well as many other images. According to Digital Dunhuang: “Constructed in the Sui dynasty and Renovated in the Five Dynasties, this cave consists of a main chamber, a corridor and a front chamber. The main chamber has a gabled ceiling in the front and a central pillar connecting the ground with the flat ceiling in the back. On the two slopes of the gabled ceiling are jataka tales painted in two horizontal bands, and on the flat ceiling are pictures of the Sui dynasty preaching scenes and painted laternendecke motifs. [Source: Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com

“The central pillar is shaped like Mt. Sumeru formed by a seven-stepped inverted pagoda on the upper and a two-stepped square base on the ground. There is a arch niche in each side of the central pillar. The east one contains the statues of a Buddha and two disciples (the one on the north side is lost) and two bodhisattva statues flanking the entrance (the one on the north side is preserved, though damaged partly). The niche has a painted lintel in bas-relief with a dragon-headed beam and pillars decorated with lotus motifs. The niche in the south side contains a statue of the Buddha and two bodhisattvas (renovated in the Qing dynasty). On each side out of the niche is a statue of bodhisattva (the one on the west side is lost). The niche in the west side contains a central Buddha flanked by two disciples renovated in the Qing dynasty. The niche in the north side also contains a three-figure group renovated in the Qing dynasty, and the two statues out of the niche are lost. Beneath the paintings on the north side of the central pillar below the niche can be seen some words "June 11 in the fourth year of Kaihuang era," which indicates when this cave was constructed (around 584 CE), hence the name "Cave of the fourth year of Kaihuang era." This inscription with exact date is not only a reliable evidence for dating the Sui dynasty caves, but also a criterion for studying the artistic styles of the caves of that period.

“A large niche with a double recesses dug out of the west wall contains a five-figure group: a central Buddha, two disciples, and two bodhisattvas (without head). Flanked the nimbus on the inner niche wall are two images of incarnated boys. The lower part out of the niche are eight bhiksunis of the Song dynasty, beneath which are traces of the Sui dynasty paintings. On the ceiling of the niche are images of ten heavenly musicians. The upper part of the south wall depicts twelve heavenly musicians, railings and draperies from west to east, and the middle part is covered with the thousand Buddha motifs, amid which is a preaching scene of the Medicine Buddha, and a double-recessed niche housing a central Buddha and two disciples (only the disciple on the west side is preserved) and two bodhisattvas on outer niche (only the one on the east is preserved). The niche lintel is decorated with honeysuckle motifs. On the back part is a preaching scene. On the junction of the south wall and the ground are nine bhiksus and male donors of the Song dynasty, beneath are traces of the Sui dynasty paintings.

“On the upper part of the north wall is a preaching scene of Sakyamuni and Prabhutaratna which was damaged by a hole dug through the wall; on the part connecting the ground are a row of the Song dynasty donor figures, beneath are traces of the Sui dynasty paintings. The top of the east wall are occupied by heavenly musicians, railings and draperties, and on the space above the entrance is a preaching scene flanked by the thousand Buddha motifs in addition to bhiksus and donors. On the tent-like ceiling of the corridor is a scene of the thousand-armed and thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara of the Song dynasty, and on each of the side walls are four dhyana Buddhas of the Song dynasty. Most of the ceiling in the front chamber has collapsed. On each side of the entrance in the west wall is a scene of Vaishravana attending Nezha\'s assembly dating back to the Song dynasty. On the upper part of the entrance are respectively an illustration of the Cintamani-cakra and of the Amogha-pasa, and the middle parts are filled with scenes of four dragons paying respect to the Buddha.”

Mogao Cave 156 (Late Tang 848-907)

Cave 156 of the Tang Dynasty (618-906) show a line of warriors According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: This cave has a truncated pyramidal ceiling and a niche on the west wall. Inside the niche is a horseshoe-shaped dais with a Buddha sitting with legs pendent (his head is destroyed). The style of the niche’s ceiling is same as the cave’s except it is rectangular. Inside the niche, the ceiling and four slopes are full of Vajrayana content which was popular in metropolitan China from the 8th century on. The images include Thousand-armed Avalokitesvra, Amoghapasa, Cintamani, Vajrasattva, etc. [Source: Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn]

“This cave was constructed in honour of Zhang Yichao who expelled the Tubo (Tibetans) and restored Chinese rule in the huge Hexi area including Dunhuang. On the north wall of the ante-chamber is an inscription entitled “Record of the Mogao Caves” written in 865, but is completely illegible now. However, a copy made previously provides valuable detailed information on the construction of the Mogao caves.

“The most striking murals are the Processions of Zhang Yichao and his wife Lady Song. Each procession scene is 8.2m long and 1.05m high, with approximately 240 persons and 110 horses in total. The processions are at the middle of the south and north walls, facing the main Buddha statue in the niche on the west wall, giving the impression they are marching towards it. Zhang’s procession, depicted in three parts and thirteen sections, starts on the south side of the entrance wall and continues on the south wall. It displays the different sections of his military forces in proper order, starting with the cavalry carrying spears or various banners with dancers and musicians on foot in between. Zhang, depicted larger in scale, is riding a white horse and about to cross a bridge, and is followed by troops composed of his clansmen. Bringing up the rear are the hunting scenes and the scene showing the supplies borne by camels and mules. The arrangement of the military forces and the supply transportation caravan match closely contemporary Tang standards.

“Lady Song’s Procession is comparable to that of her husband, but somewhat different in character. Preceding her is a troop of entertainers, acrobats, dancers and a band, instead of soldiers. She is also riding a white horse, accompanied by nine mounted female attendants who all are holding objects in their hands, such as censers or toiletries. At the end of her procession are hunters and camels carrying luggage similar to that in her husband’s. The five large carts and two hexagonal pavilions display the life style of the nobility and the form of transportation at that time.

“The unique depiction of these two processions marks a significant change in donors’ portraits at Dunhuang. The contents of the painting do not demonstrate how the Zhangs (and their successors) were devoted to the Buddha although they were Buddhists. Being the key images themselves, they just wanted to demonstrate their political power and social status. At the same time, these paintings provide lively and precious examples of a parade genre, particularly when there are no other surviving ones.

“In the depiction of the Western Paradise, a pair of dancers is performing. One of them is beating a long drum, while the other is playing a four stringed pipa on her back. Pipa was imported from Kucha (then a centre of music in Central Asia, in present-day Xinjiang) and became very popular from the early Tang on. It was played with a large plectrum at that time (it is played with fingers or imitative long nails today). Beside them are the musicians sitting on the floor playing different instruments. This style of entertainment was extremely popular during that dynasty.”

Mogao Cave 23 (High Tang 705-781AD)

Caves 23 show workers in the fields. According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: This cave has a truncated pyramidal ceiling with a lotus motif in the zaojing (square inset ceiling). The murals on the walls mainly depict the narrative scenes relating to the Lotus Sutra. The interpretation of the philosophy in the Buddhist sutra is presented very skillfully in the paintings in this cave.[Source: Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn] “Surrounding the central scene are different chapters of the sutra. One of them is the famous scene “The Farmers Working in Heavy Rain”, which depicts the Parable of the Herbal Medicine Chapter. The sky is cloudy and it is raining hard. One farmer is whipping the cow to plough as the other one is carrying the harvest on his shoulders. The cow was painted using the yun-ran technique, which was in vogue at this time. Below the cow, two farmers (perhaps father and son) are enjoying a meal delivered by a woman who watches them eat. It is a vivid depiction of village life at that time.

“At the lower-left corner, children are building a stupa with sand while playing. According to the Lotus Sutra, even a person spending just a short moment doing good deeds, such as building a stupa to worship, will attain Buddhahood. Other children are playing music and dancing. The scene appears to show the children celebrating a festival or harvest, which may actually reflect the artist’s intent. At the centre of the north wall is a scene of Sakyamuni Preaching in Vulture Peak, one of the popular places where he preaches. The Buddha, in a red robe, is depicted as an intelligent master, more like a human being than an unreachable deity. The green and blue landscape at his back shows a view of the mountain. Flanking the Buddha are the two great Bodhisattvas, Manjusri and Samantabhadra, riding a lion and an elephant, respectively. Many other Bodhisattvas are emerging from the ground. In the sky, the clouds appear as a canopy over the whole scene, creating a very elaborate composition.

“In the centre of the south wall, Prabhutaratna (the long-extinct Buddha) and Sakyamuni (the present Buddha) sit side-by-side in a stupa. It emphasizes the importance of the doctrine of the Lotus Sutra by the approval of a past Buddha. It also symbolizes the infinite nature of Buddha. This has been a very popular scene in the caves since the Northern Wei, but it is quite rare to be presented as the main theme on a whole wall. The depiction of the two Buddhas is outstanding, as is the painting of the stupa. The body of the stupa looks like a Chinese pavilion. On top is another stupa, a style which is often seen in murals in the Tang caves. On the north side of the east wall are many stupas and buildings. However, no conclusion has been reached on which sutra is being depicted here. Although the painting has been fading, its fine outlines with mild and light colours are still visible. It weaves a calm and quiet scene. “

Mogao Cave 61 (Five Dynasties 907-960)

Cave 61 features a celebrated landscape of Mount Wutai and is an early example of artistic Chinese cartography, where it seems like nothing has been left out — mountains, rivers, cities, temples, roads and caravans are all depicted. According to the Dunhuang Research Academy: It is one of the largest caves (14.1m deep, 13.57m wide) in Dunhuang. Its gorgeous paintings are very famous for their size and majesty. This cave is also known as the Manjusri’s Hall because it was devoted to him. His big statue was originally on the horseshoe shaped dais in front of a tall screen which rises all the way to the ceiling. The statue is now missing; the only thing remaining is the tail of his mount, a lion. [Source: Dunhuang Academy, February 26, 2014, public.dha.ac.cn ]

“Behind the altar, the immense panorama of Mount Wutai (Shanxiprovince), sacred to him, occupies the whole upper part of the west wall. The painting is 13.8m long and 3.8m high. It depicts the landscape, activities of people, and more than 170 buildings including monasteries, stupa, and bridges with legible inscriptions. It corresponds closely with the actual site, making it a valuable historical record of an ancient map. Together with the illustrations ofjingbian, farmers, pottery makers, hunters, butchers, banquet and entertainment scenes of the contemporary life style are shown.

“Below the map is the illustration of Sakyamuni’s life story depicted in fifteen scenes, from his Birth to the Great Departure. Ten out of the eleven jiangbian in this cave are very detailed. One of these illustrated narratives is the story of Prince Good Friend, from theSutra of Requiting Blessing Received which presents the orthodox Confucian thought of loyalty and filial piety in the theme of Buddhist art. This sutra is believed to be composed in China between the 5th and 6th centuries to match traditional Chinese values. It started to appear in Dunhuang at the end of the Tang and was one of the most popular sutras during the Five Dynasties. One of its stories is same as the jataka tale of Prince Good Conduct in Cave 296. The four slopes are decorated with the Thousand-Buddha motif and a border of identical preaching groups. All of these repeated images would have been executed with the aid of paper stencils bearing pricked outlines for easy transfer to the mural. A stencil of this kind kept at the British Museum is very close in both style and general proportions to the designs in this cave.

This cave features the Four Devaraja (Heavenly Kings) depicted on the four lower corners of the sloping faces of its truncated pyramidal ceiling as guardians of the cave and devotees. Together with the processions of the donors painted on the walls in life size, they are the two main characteristics of the caves excavated in the Five Dynasties.

Another notable point is the frequent depiction of the debate between Manjusri and Vimalakirti on the east wall beside the entrance since the Tang dynasty. Vimalakirti usually occupies the place of honour on the left (southern side) because he was considered the protagonist since he reached enlightenment as a layman. However, in this cave and Cave 98 (constructed at the same time), their positions are reversed and Manjusri is on the southern side. From the mid-Tang on, the faith in Manjusri has been very popular, especially in Khotan, the ally of the then Dunhuang rulers. The Khotanese had very deep faith in both Manjusri and the Northern Heavenly King.

“Portraits of donors increased in number and size in the Five Dynasties and the Song. When the local magnate Cao Yuan-zhong was in power, they supported the renovation of existing caves and the construction of new ones, including Caves 61, 98, 100 & 108. The Caos controlled the Hexi area for 122 years. They formed alliances with their neighbours (the Uyghurs and the Khotan), and the local elites, as noted by the inscriptions beside the portraits in the caves. Images of the family and their relatives are depicted in life-size or even larger. The Caos’ female members were all painted with elaborate attire and jewelry. Even the make-up on their faces is still clearly visible today.

“On the side walls of the corridor are the image of Tejaprabha Buddha accompanied by the Nine Luminaries on the south side, and the zodiac signs (Figure 5) with a group of monks on the north with Tangut and Chinese inscriptions. These paintings were added in the Yuan (1271-1368) when the antechamber was converted to “Huang-qingTemple” and restored in 1351. Tejaprabha Buddha is worshipped to dispel natural disasters which happened quite often during the years (1312-1313) when this mural was being painted. Also it is believed the planets are supervised by Manjusri, therefore these images are depicted in the Manjusri’s Hall.”

Preserving Mogao Caves

The rock art ensemble at Mogao is administered by the Dunhuang Cultural Relics Research Institute. In the 1960s the eroded face of the cliff was reinforced with a functional but unattractive concrete facade. In 1987, the Mogao Caves were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Iron doors have been placed at the entrance of the caves and a five-kilometer-long fence has been installed to keep out dust and unwanted visitors.

Mogao Caves has been badly damaged by tourism. The carbon dioxide and moisture released from the breath of visitors has caused paint to peel and statues to crack and fragment. Paintings are also being damaged by salt leaching from underlying rock.

Authorities have tried to protect the caves by only opening 20 or 30 caves at a time and prohibiting photography and restricting visits to a short period of time. Restoration work has been being overseen since 1989 by the Getty Conservation Institute, which has done outstanding work preserving tomb paintings in Egypt. The Getty Institute has installed knitted-textile fences, planted trees and installed fabric screens at cave entrance to reduce that amount of sand and carbon dioxide that enters the caves.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Today East and West are converging again on Dunhuang, this time to help save the grottoes from what may be the biggest threat in their 1,600-year history. Mogao's murals have always been fragile, the thinnest tissue of paint caught in a corrosive battle between rock and air. Over the past few years, they have faced the combined assault of natural forces and a surge of tourists. In an effort both to conserve the Silk Road masterpieces and to contain the tourists' impact, Fan has enlisted the help of teams of experts from across Asia, Europe, and the United States. It is a cultural collaboration that echoes the glorious history of the caves — and may help ensure their survival. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

“Fan Jinshi didn't set out to be the guardian of the caves. Back in 1963, when she reported to the Dunhuang Academy, the 23-year-old Shanghai native never imagined she would last a year in the forsaken outpost, much less a lifetime. The Mogao caves were impressive, to be sure, but Fan couldn't bear the food, the lack of running water, or the fact that everything — houses, beds, chairs’seemed to be made out of mud.

“Then came the Cultural Revolution in 1966, when Chairman Mao's regime laid waste to Buddhist temples, cultural artifacts, and foreign emblems across China. The Mogao caves were a natural target. Fan's group didn't avoid the ferment; the staff of 48 split into about a dozen revolutionary factions, then spent their days condemning and interrogating each other. But for all the bitter infighting, the factions agreed on one principle: The Mogao caves should not be touched. Says Fan, "We nailed shut all the gates to the grottoes."

“Nearly half a century later, Fan is leading a very different sort of cultural revolution. As afternoon sunlight streams into her office at the Dunhuang Academy, the director — a diminutive woman with short salt-and-pepper hair — gestures out the window toward the dun-colored cliff face. "The caves have almost every ailment," she says, rattling off the damage caused by sand, water, soot from fires, salt, insects, sunlight — and tourists. Fan oversees a staff of 500, but she recognized as far back as the 1980s that the academy could use the help of foreign conservationists. This may sound simple, but collaborating with foreigners is a sensitive issue at Chinese cultural heritage sites — and the plunder of the Mogao caves a century ago serves as a powerful cautionary tale.

“The sky outside Fan's window, cloudless and eggshell blue for days, suddenly darkens. A sandstorm has kicked up. Fan notices only long enough to remember the first project she undertook with one of the academy's longest serving partners, the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI). To prevent the kind of sand invasion that had buried some of the caves — and damaged paintings — GCI erected angled fences on the dunes above the cliff, reducing wind speeds by half and decreasing encroachment by 60 percent. Today the academy has dispatched bulldozers and workers to plant wide swaths of desert grasses to perform the same job.

“The most painstaking efforts occur inside the caves. GCI has also set up monitors for humidity and temperature in the caves and is now measuring the flow of tourists as well. Its biggest project took place in Cave 85, a Tang Dynasty (618-906) grotto where GCI and academy conservationists worked for eight years devising a special grout to reattach mural segments that had separated from the rock face.”

Digitalizing Mogao Caves and Caves Open to Tourists

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “At a site this old, ethical ambiguities abound. In Cave 260, a sixth-century grotto that the University of London's Courtauld Institute of Art is using as a "study cave," Chinese students recently used micro-dusters to clean the surfaces of three small Buddha images. Almost invisible before, the Buddha's red robes suddenly sparkled. "It's wonderful to see the painting," says Stephen Rickerby, a conservator who is coordinating the project. "But we're ambivalent. The dust contains salts that can damage the paint, but removing the dust exposes it to light that will cause it to fade." [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

“This is the dilemma Fan Jinshi faces: how to conserve the caves while exposing them to a wider audience. The number of tourists visiting Mogao reached more than half a million in 2006. The income has buoyed the Dunhuang Academy, but the moisture from all the breathing could damage the murals more than any other factor. Tourists are now limited to a rotating set of 40 caves, ten of which are open at any given time.

“Digital technology may provide one solution. Following up on a photo-digitization project completed in 23 caves with the Mellon International Dunhuang Archive, the academy has launched its own multiyear marathon to digitize all 492 decorated caves (so far, the staff has completed 20). The effort mirrors an international push to digitize the scattered scrolls from Cave 17.

“Fan's dream is to bring together digital archives from East and West to re-create the full three-dimensional experience of the caves — not at the site itself, but in a sleek new visitor's center proposed to be built 15 miles away. The center has not yet moved beyond the planning stages. But Fan believes that reuniting all of Mogao's treasures in one place, even virtually, will guarantee that their glories will never again be buried in the sand. "This will be a way," Fan says, "to preserve them forever."”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn ; Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn ; CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020