EVOLUTION OF CHINESE SHIPS

Song river boat

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “An important advance in shipbuilding used since the second century in China was the construction of double hulls divided into separate watertight compartments. This saved ships from sinking if rammed, but it also offered a method of carrying water for passengers and animals, as well as tanks for keeping fish catches fresh. Crucial to navigation was another Chinese invention of the first century, the sternpost rudder, fastened to the outside rear of a ship which could be raised and lowered according to the depth of the water, and used to navigate close to shore, in crowded harbors and narrow channels. Both these inventions were commonplace in China 1,000 years before their introduction to Europe. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Chinese ships were also noted for their advances in sail design and rigging. Bypassing the need for banks of rowers, by the third and fourth centuries the Chinese were building three- and four-masted ships (1000 years before Europe) of wind-efficient design. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries they added lug and then lateen sails from the Arabs to help sail against the prevailing winds.

“By the eighth century, ships 200 feet long capable of carrying 500 men were being built in China (the size of Columbus' ships eight centuries later!) By the Song Dynasty (960-1279), these stout and stable ships with their private cabins for travelers and fresh water for drinking and bathing were the ships of choice for Arab and Persian traders in the Indian Ocean. The Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) encouraged commercial activity and maritime trade, so the succeeding Ming Dynasty inherited large shipyards, many skilled shipyard workers, and finely tuned naval technology from the dynasty that preceded it.

“Because the Yongle emperor wanted to impress Ming power upon the world and show off China's resources and importance, he gave orders to build even larger ships than were necessary for the voyages. Thus the word went out to construct special "Treasure Ships," ships over 400 feet long, 160 feet wide, with nine masts, twelve sails, and four decks, large enough to carry 2,500 tons of cargo each and armed with dozens of small cannons. Accompanying those ships were to be hundreds of smaller ships, some filled only with water, others carrying troops or horses or cannon, still others with gifts of silks and brocades, porcelains, lacquerware, tea, and ironworks that would impress leaders of far-flung civilizations.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD: PRODUCTS, TRADE, MONEY AND SOGDIAN MERCHANTS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD ROUTES AND CITIES factsanddetails.com; MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; DHOWS: THE CAMELS OF THE MARITIME SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF SILK AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.- A.D. 220): WU DI, ROMANS, SOGDIANS AND PARTHIANS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD DURING THE TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618 - 907) factsanddetails.com; MONGOLS AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD, BYZANTIUM AND VENICE factsanddetails.com; END OF THE SILK ROAD AND RISE OF THE EUROPEAN SILK INDUSTRY AND SILK ROAD TOURISM factsanddetails.com; CARAVANS AND TRANSPORTATION ALONG THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD AND BACTRIAN CAMELS AS CARAVAN ANIMALS factsanddetails.com; CAMEL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; CHINA’S GIFTS TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com; IDEAS INTRODUCED FROM CHINA TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com; SILK, SILK WORMS, THEIR HISTORY AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com; MONGOLS, CHRISTIANITY, NESTORIANS AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan, Laurence Kennedy, et al. Amazon.com; “The Silk Road: A New History” by Valerie Hansen Amazon.com; “Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present” by Christopher I. Beckwith Amazon.com; “Life Along the Silk Road” by Susan Whitfield Amazon.com; “Fujian in the Sea: Fujian and the Maritime Silk Road” (Illustrated Fujian and the Maritime Silk) by Shuoxuan Chen and Bizhen Xie Amazon.com ; “When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles” by Metropolitan Museum of Art, Anne Wardwell, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Travels of Marco Polo” by Marco Polo and Ronald Latham Amazon.com

Zheng He's Ming-Era Treasure Ships

Sponsored by the Yongle Emperor to show the world the splendor of the Chinese empire, the seven expeditions led by the Imperial eunuch Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 were by far the largest maritime expeditions the world had ever seen, and would see for the next five centuries. Not until World War I did there appear anything comparable. Overall He visited more than 30 countries and by some estimates covered 160,000 sea miles (about 300,000 kilometers).

Sponsored by the Yongle Emperor to show the world the splendor of the Chinese empire, the seven expeditions led by the Imperial eunuch Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 were by far the largest maritime expeditions the world had ever seen, and would see for the next five centuries. Not until World War I did there appear anything comparable. Overall He visited more than 30 countries and by some estimates covered 160,000 sea miles (about 300,000 kilometers).

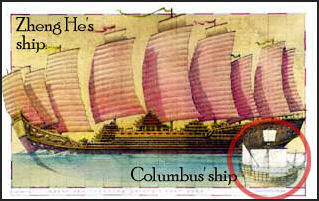

The largest expedition utilized a crew of 30,000 men and a fleet of 317 ships, including a 444-foot-long teak-wood treasury ship with nine masts, the largest wooden ship ever made; 370-foot, eight-masted “galloping horse ships," the fastest boats in the fleet; 280-foot supply ships; 240-foot troop transports; 180-foot battle junks, a billet ship, patrol boats and 20 tankers to carry fresh water. The expedition was nothing less than a floating city that stretched across several kilometers of sea. By contrast to Columbus' expedition consisted for three ships with 90 men. The largest ship was 85 feet long. The largest ships in Vasco de Gama's fleet had four masts and were about 100 feet long.

The crew included sailors and mariners, seven grand eunuchs, hundreds of Ming officials, 180 physicians, geomacers, sail makers, blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, cooks, merchants, accountants, interpreters that spoke Arabic and other languages, astrologers that predicted the weather, astronomers that studied the stars, pharmacologists that collected plants, ship repair specialists, and even protocol specialist that were responsible for organizing official receptions. To guide the massive ships, Chinese navigators used compasses and elaborate navigational charts with detailed compass bearings.

During the seven expeditions the treasure ships carried more than a million tons of Chinese silk, ceramics and copper coins and traded them for tropical species, gemstones, fragrant woods, animals, textiles and minerals. Among the things that the Chinese coveted most were medicinal herbs, incense, pepper, tropical hardwoods, peanuts, opium, bird's nests, African ivory and Arabian horses. The Chinese were not interested in Europe, which only had wool and wine to offer---things the Chinese could produce for themselves.

The vessels In Zheng He's fleet contained watertight compartments that prevented water in one part of the hull from flooding the whole ship---an advancement first developed by the Chinese in the Han period that would not appear in European vessels for several hundred after Zheng He. The compartments were created from bulkheads, a series of upright partitions that divided the ship's hold and prevented the spread of leakage or fire.

Imperial-Era Chinese Ships

Evan Hadingham of NOVA wrote: ““The first Chinese oceangoing trade ships were built far back in the Song dynasty (c. 960-1270). But it was the subsequent Mongol emperors (the Yuan dynasty of c. 1271-1368) who commissioned the first imperial treasure fleets and founded trading posts in Sumatra, Ceylon, and southern India. When Marco Polo made his famous journey to the Mongol court, he described four-masted junks with 60 individual cabins for merchants, watertight bulkheads, and crews of up to 300. “When the Han Chinese overthrew the Mongols and founded the Ming dynasty in the later 14th century, they took over the fleet and an already extensive trade network.+|+ [Source: Evan Hadingham, NOVA, January 16, 2001 +|+]

Song junk

European explorers to China were amazed by how much larger the Chinese ships were than their counterparts in the West. Ming accounts described “ships which sail the Southern Sea are like houses. When their sails are spread they are like great clouds in the sky." The smallest vessels were five-masted combat ships that measured 180 by 68 feet. The largest were colossal multi-storied ships, 400 feet long, 170 feet across at the beam, with nine masts, a 50,000 square foot main deck and a displacement of 3,000 tons. All the ships of Columbus and de Gama would have fit on the deck of the largest Chinese ships. Only the most massive wooden warships of the Victorian age approached these lengths, and several of these vessels suffered from structural problems that required extensive internal iron supports to hold the hull together. No such structures are reported in the Chinese sources.

For centuries, historians thought stories of enormous Chinese ships had to be exaggerations. In 1962, workers unearthed a 36-foot-long wooden steering post in a trench in the Yangtze River in Nanjing. The post was large enough to connect to a rudder that covered an astonishing 452 square feet, large enough to steer a massive ship. Hadingham wrote: The rudderpost was excavated in the ruins of one of the Ming boatyards in Nanjing. This timber was no less than 36 feet long. Reverse engineering using the proportions typical of a traditional junk indicated a hull length of around 500 feet.” +|+

“Unfortunately, other archeological traces of this "golden age" of Chinese seafaring remain elusive. One of the most intensively studied wrecks, found at Quanzhou in 1973, dates from the earlier Song period; this substantial double-masted ship probably sank sometime in the 1270s. Its V-shaped hull is framed around a pine keel over 100 feet long and covered with a double layer of intricately fitted cedar planking, thus clearly indicating its oceangoing character. Inside, 13 compartments held the residue of an exotic cargo of spices, shells, and fragrant woods, much of it originating in east Africa. +|+

“The Quanzhou wreck suggests that over a century before Zheng He's fabled voyages, the Chinese were already involved in ambitious trading exploits across the Indian Ocean. Even back then, their sturdy ships equaled the largest known European vessels of the period. By inventing watertight compartments and efficient "lugsails" that enabled them to steer close to the wind, Chinese shipbuilders remained ahead of the West in the following centuries.

Quanzhou boat

Export Porcelains

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Chinese porcelain was not only a major trade item with other lands, it also came to reflect the influences of the diverse cultures it came in contact with. For example, Changsha porcelains of the Tang dynasty were frequently painted with Islamic-style decoration, and cobalt-blue décor popular in the Middle East appears to be closely related to the underglaze-blue porcelains of the Yuan dynasty. Both examples reflect the cultural interaction produced by the longstanding contact between China and Arab regions by means of trade.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“With the discovery of new navigation routes in the late fifteenth century, European ships began to make their way to the East in increasing numbers, expanding the distribution of Chinese porcelains made for foreign trade to Europe and the West from the original areas in Asia and Africa, creating a truly global network for trade and commerce in this product. The fondness for underglaze-blue porcelains and those fired-to-order resulted in an upsurge in production and circulation, making it one of the most attractive commercial products of this age. \=/

“Furthermore, various areas in Asia, including the Korean peninsula, Japan, the Indochinese Peninsula, and even the Middle East, the ceramics industry also flourished, supplying not only the needs of their own lands but also in trade with neighbors. However, from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, China's exports of porcelain overseas declined several times due to changes in overseas trade policies, stimulating a gradual rise in the ceramics industry of areas in Southeast Asia and Japan. Not only did production increase dramatically in terms of quantity and quality, their wares were even shipped throughout Asia and to Europe. \=/

Diversity of Chinese Export Porcelains

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the millennium between the ninth and nineteenth centuries, porcelains either whole or in fragmentary form found in sunken ships along the "Silk Route of the Sea," collected along the seashore, excavated from archaeological sites on land, or displayed in the collections of Chinese ceramics of European nobility all present us with a spectacular view of Chinese export porcelains. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

”To meet the demand of foreign markets, kilns in China often blended exotic elements into the ceramic products they made, producing new forms of glaze decorations and vessel types. Examples include painted from the Changsha kilns and underglaze-blue wares with their Islamic touch. After the sixteenth century, the manufacturers of various export porcelains frequently received orders from Europe, providing pieces for everyday use and fine works for collecting that were coveted around the world.” \=/

Examples of different kinds of export porcelain include: an ewer with bird painting in copper red from from Changsha ware, Hunan province Late Tang dynasty, 9th century; a bowl in bluish-white glaze, Jingdezhen ware, Jiangxi Province, Song dynasty (960-1279); a bowl with floral décor in underglaze blue, Yuan dynasty 1379-1468; a gourd-shaped flask with scholars in a garden in underglaze blue, Late Ming dynasty(1368-1644); a dish with floral décor in underglaze blue and gold, Jingdezhen ware, Jiangxi province Qing dynasty, 17th to 18th century.

Spread of Ceramics for Trade

Song celadon

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The porcelains were mostly fired at kilns along China's southeast coast to meet the demands of the export trade. These include celadons and shadowy blue glaze wares made to supply various places in Asia. Small vases and jars were shipped to the Philippines, and kendi water vessels were commonly used in Southeast Asia. Arab traders were also quite active in sea trade, which is why the Changsha wares and Yuan dynasty underglaze-blue ceramics came to be distributed far and wide, including the Persian Gulf and East Africa. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“High-temperature fired porcelains, solid and refined with lustrous glaze and painted decoration, came to be coveted by purchasers in many places around the world. After the discovery of new sea routes, the love of Chinese porcelains not only became widespread, it even transformed the dinnerware habits of Europeans, who viewed "china" as "exotica" for collecting. These precious rarities, as still seen today, were often preserved in the castles and palaces of European nobility. \=/

“In the second half of the sixteenth to first half of the seventeenth century, Europeans actively placed orders for specially designed porcelains from Chinese manufacturers. Among them, underglaze-blue vessels with radiating segmented designs were the most popular and became commonly known as "Kraak" porcelain. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, porcelains painted with family coat of arms were quite popular and also used to demonstrate social standing.” \=/

In February 2003, about 100 kilometers off Cirebon on the north Java coast, local fishermen caught ceramic objects in their dragnets. They were part of wreckage found at a depth of 56 meters in the Java Sea subsequently named the Cirebon cargo. The local Indonesian fisherman alerted divers and treasure hunters. The site was salvaged between April 2004 and October 2005. It took a team of international divers nearly 22,000 trips to recover the jewels and other goods buried with the boat. The first of these wares surfaced in April 2004. Providing evidence of a vigorous export trade was the largest amount of Yue wares or yue yao, found, forming 75 per cent of the cargo. Ten per cent of the 200,000 pieces was intact, including Yue ewers with bulging bellies, bowls, platters and incense burners as well as figurines of birds, deer and unicorns. [Source: Yvonne Tan, Asian Art Newspaper May 2007 /]

See Separate Article: EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Exchanges in the Art and Craft of Ceramics

porcelain vase

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the government put into effect phased prohibitions in terms of foreign trade. Various countries around Asia took advantage of this emerging trade opportunity by promoting their local ceramics in other regions. By the fifteenth century, for example, both Vietnam and Thailand made porcelains with Chinese-style decoration and glaze coloring, supplying the demand across a wide area in East and Southeast Asia and even as far as the Middle East. By the early seventeenth century, Japanese Hizen porcelain (Imari ware) first imitated Chinese porcelains and then further added gold and silver to the colored painting to create a splendid quality that in turn became treasured by European collectors. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“After the middle of the fourteenth century, northern Vietnam began producing underglaze-blue porcelains with Yuan and Ming dynasty styles, and these were exported in large numbers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The light and elegant glaze colors of these porcelains along with the gentle lines of the decoration and bright white blank areas give them a distinctive quality. Also often added to the patterns of underglaze-blue wares were overglaze enamels or gold painting, creating a luxurious effect. Vietnamese porcelains were generally exported throughout Asia and even as far as Fustat in Egypt. \=/

“The fifteenth century was a golden age for export porcelains in Thailand. Ceramics production flourished most in the central Thai area, and their export porcelains can be found in archaeological sites and boat wrecks all across Asia. Most of the vessels fired were utilitarian in nature, such as bowls and plates. There were also carved and incised celadons imitating forms produced at China's Longquan kilns, oxidized iron being the coloring agent for painting patterns in the decoration of these imitation underglaze-blue forms. Among the latter, painted linear designs of picked flowers or fish are the most representative. \=/

“In the early seventeenth century, the Hizen area of Kyushu in Japan began firing porcelains in Chinese styles. Since they were loaded at the port of Imari for sale, they also became known as "Imari porcelains." Later, to the underglaze-blue was added colors as well as gold painting, creating innovative and beautiful porcelains that were in great demand throughout Asia and Europe.” \=/

Discovery of Silk Road Ships

In the 1998 sea cucumber divers working in the Gelesa Straight found some coral-encrusted ceramics, and further scraping away revealed a 9th century Arab dhow laden with 60,000 handmade ceramics and some pieces of gold and silver. Much of the cargo was made of up cheap, mass-produced, Chinese-made bowls, known as Changsa bowls, placed n large storage jars. There was also ink pots, spices jars of various sizes and ewers. [Source: Simon Worrall, National Geographic, June 2009]

The destination of the ship appeared to be Middle East, meaning that ship was traveling the maritime Silk Road. Many of the bowls were decorated with geometric decorations and Koranic motifs that were clearly intended for Middle Eastern market. This implied she objects were made to order for Middle Eastern customers.

The dhow was almost 20 meters long. It resembled a kind of sailing dhow still used in Oman called a baitl qarib. Built of African and Indian wood, it had a raked prow and stern and was fitted with square sails and made of planks sewn together with coconut husks fiber.

In December 2007, an 800-year-old, 30-meter-long merchant vessel, filled with porcelain and other antiquities, was raised from the bottom of the ocean with a crane in waters off the south China coast near Yangjiang, Guangdong Province. Discovered in 1987, the vessel has yielded 4,000 containers made of gold, silver and porcelain as well as 6,000 Song dynasty copper coins. The boat is expected ti provide insight into maritime trade during the Song dynasty.(960-1279), when the vessel was built.

Tang-Era Arab Shipwreck

In 1998, sea cucumber divers working off Belitung, an island on the east coast of Sumatra, in the Java Sea, found some coral-encrusted ceramics, and further scraping away revealed a 9th century Arab dhow laden with 60,000 handmade ceramics and some pieces of gold and silver. Much of the cargo was made of up cheap, mass-produced, Chinese-made bowls, known as Changsa bowls, placed n large storage jars. There was also ink pots, spices jars of various sizes and ewers. [Source: Simon Worrall, National Geographic, June 2009]

Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop wrote in the New York Times, “For more than a decade, archaeologists and historians have been studying the contents of a ninth-century Arab dhow that was discovered in 1998 off Indonesia’s Belitung Island. The sea-cucumber divers who found the wreck had no idea it eventually would be considered one of the most important maritime discoveries of the late 20th century. The dhow was carrying a rich cargo “ 60,000 ceramic pieces and an array of gold and silver works “ and its discovery has confirmed how significant trade was along a maritime silk road between Tang Dynasty China and Abbasid Iraq. It also has revealed how China was mass-producing trade goods even then and customizing them to suit the tastes of clients in West Asia. [Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, March 7, 2011]

Model of wrecked tang ship

“Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds,” an exhibition that opened at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore in 2011 and was put together by the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Smithsonian Institution in Washington, featured amny artifacts from the belitung shipwreck. “This exhibition tells us a story about an extraordinary moment in globalization, “Julian Raby, director of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, told the New York Times. “It brings to life the tale of Sinbad sailing to China to make his fortune. It shows us that the world in the ninth century was not as fragmented as we assumed. There were two great export powers: the Tang in the east and the Abbasid based in Baghdad.”

Until the Belitung find, historians had thought that Tang China traded primarily through the land routes of Central Asia, mainly on the Silk Road. Ancient records told of Persian fleets sailing the Southeast Asian seas but no wrecks had been found, until the Belitung dhow. Its cargo confirmed that a huge volume of trade was taking place along a maritime route, said Heidi Tan, a curator at the Asian Civilisations Museum and a co-curator of the exhibition.

Mr. Raby said: “The size of the find gives us a sense of two things: a sense of China as a country already producing things on an industrialized scale and also a China that is no longer producing ceramics to bury.” He was referring to the production of burial pottery like camels and horses, which was banned in the late eighth century. “Instead, kilns looked for other markets and they started producing tableware and they built an export market.”

See Separate Article: EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Artifacts from the Tang-Era Arab Shipwreck

stoneware storage jars on wrecked Tang ship

“Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds” featured only 450 of the 60,000 objects found in the shipwreck but the rows of similar bowls that were displayed underscored the importance and size of the find. Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop wrote in the New York Times, ‘stacked in the dhow, hundreds of tall stoneware jars each held more than a hundred nested Changsha bowls “ named after the Changsha kilns in Hunan where they were produced. Of the thousands of hand-painted pieces, almost all carry one of a few set patterns, but these were copied by many hands, resulting in an impression of huge variety.

Not all of the ceramics were mass-produced. Among the most interesting pieces in the exhibition is an extremely rare dish, one of three found in the wreck, with floral lozenge motifs surrounded by sprigs of foliage. They are believed to be the earliest known complete Chinese blue-and-white ceramics.

Ms. Tan, the curator, said: “It demonstrates that the Chinese potters were already experimenting with imported cobalt blue from Iraq, which they applied as underglaze painted decoration, some 500 years earlier than the famous blue and white porcelain of the 14th century.” At the time of the dhow’s discovery, cobalt-blue pigments had been found only in the Middle East, not yet in China, said Alan Chong, director of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Aside from the rare ceramics, the haul also contained gold and silver objects, some of which Mr. Raby of the Smithsonian described as “of the very best quality you can see, clearly of imperial quality, “adding, ‘so we believe these were possible diplomatic gifts.” The form and decorative motifs of an octagonal gold cup “ musicians and dancers with long hair and billowing robes “ suggest Central Asian metal wares. Mr. Raby said it was believed to be the largest known such gold cup from Tang China, even upstaging, he added, one of the great treasures of Tang gold and silver work: the so-called Hejiacun Hoard, found in what had been one of the southern suburbs of the Tang capital of Xian.

Ming-Era Pirate Ship Found in the Marine Silk Road

items from Tang shipwreck

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: Just off the coast of the southern Chinese island of Nan'ao, Chinese archeologists are excavating the underwater wreck of a Ming-era ship. Named the Nan'ao Number One, the wreck lies along a stretch of ocean that Chinese historians regard as the country's "Marine Silk Road." During China's heyday as a maritime power during and shortly after the Song Dynasty (A.D. 960-1279), the route was popular with traders but prone to dangerous storms, resulting in a trail of sunken ships. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

In this litter of wrecks the Nan'ao Number One is unique. It is the only known wreck from the late Ming Dynasty. Archaeologists estimate the ship sailed between 1573 and 1620, a period when China had turned inward, banned maritime commerce, and begun to dismantle its once-great fleets. In another time, the vessel would have been a merchant ship, following a busy trade route. But when China closed its shores and docks, maritime trade and commerce became piracy and smuggling. Officially, the Nan'ao ship never should have been in the water---it was likely moving along the coast illegally.

The Nan'ao ship is a rare find, but its fate is a familiar one in this part of the ocean. "This is a dangerous passage," Chinese archaeologist Cui Yong told Archaeology. As the boat snuck along the coast, something, whether bad weather or hidden rocks, caused it to sink and deposit its load of contraband---ceramics, copper coins, and ironware---onto the sea floor.

The wreck, which contains more than 10,000 pieces of Ming Dynasty porcelain, much of it still stacked for transport, was discovered in 2007 bylocal fishermen who pulled Ming Dynasty porcelain out of the ocean with their catch. When Cui arrived at the island and made his first dive, the Nan'ao site proved better than he had imagined. The wreck was unusually well preserved and the conditions were good for excavating. It was deep, but the water was clear and the mud at the bottom of the ocean soft and manageable. "I got lucky," he says.

The Nan'ao sank at the mouth of a particularly dangerous stretch of water. It sits at the northern edge of present-day Guangdong Province, near the entrance to the strait between the coasts of China and Taiwan. Typhoons frequent this passage and could blow shipsinto hidden rocks or smash them along the coast.

Underwater Excavations of the Ming-Era Pirate Ship

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: Excavations at the site move painstakingly slowly. Because of the depth of the site, around 90 feet down, a diver is only allowed 25 minutes at the bottom and only one dive a day. If a storm hits, or if the wind is simply too high, no one dives. This, says Cui, generally rules out fieldwork nine months of the year. And even on good days, he is concerned for the safety of his divers. They descend in pairs and keep close tabs on bottom time. Cui is quick to point out one of the key features on his boat is a decompression chamber. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

Cui's excavation team was given permission to begin digging in 2009. Since then he has spent as much time as weather permits floating above Nan'ao Number One. After one excavation season, nearly half the wreck is exposed. The top decks have been worn away, but its belly lies undisturbed, oriented along a northnsouth line. Two curves of wood are exposed toward the stern, hemming in rows of porcelain bowls, platters, and cups, many still stacked neatly. On excavation maps, archaeologists have filled in where they speculate the sides of the boat continue, and they estimate the Nan'ao runs around 90 feet from bow to stern.

The excavation of the Nan'ao and tales of a Ming Dynasty pirate ship attracted a fair amount of attention. Wrecks like the Nan'ao, Cui said, help attract media and increase government funding. But the increased exposure also attracts looters and adds pressure. It is a delicate balancing act involving journalists sharing deck space on his boat with border patrol officers in fatigues and orange life jackets. The border guards help retrieve and clean pieces of porcelain as they come up from the wreck and remain on guard even beyond the excavation season because the risk of looting by local fishermen is high.

Piracy in the Time of the Ming-Era Pirate Ship

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: The fact that the Nan'ao wreck has any artifacts at all is testament to the determination of Ming Dynasty businessmen. Boats caught defying the ban on maritime trade could be scuttled and their crews thrown in jail. These deterrents did not keep the Nan'ao merchants down’they simply became smugglers. "The ban was regularly ignored in southern China," says Wu Chongming, a colleague of Cui's who teaches at the Maritime Archaeology Research Center at Xiamen University in Fujian. Some historians theorize that the ban on international trade was originally intended to starve increasingly bold Japanese pirates. Rather than give up the business, Chinese merchants turned to piracy themselves---both smuggling and raiding. The Chinese still called smugglers and raiders wokou, a derogatory term for Japanese pirates, but just a few years into the ban, Chinese pirates had taken over the South China Sea. "There is a saying in Chinese," says Wu. "When the market closes, all the businessmen become smugglers." [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

Items Found on the Ming-Era Pirate Ship

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: The pieces Cui's team are bringing up were likely not the most valuable items onboard, explains Cui. They were probably, in fact, an afterthought for the Ming Dynasty smugglers. "It was probably ballast," says Cui. Other cargo, such as tea or the strings of copper coins that have been found on the wreck, would have been the ship's real treasure. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

Chen Huasha, a researcher from the Beijing Palace Museum, who has spent time on the Nan Tianshun for two years running, believes the bulk of the porcelain uncovered comes from kilns that were operating in China's Fujian and Jiangxi provinces. When asked how she can tell, Chen says, "There are characteristics." Chen selects a large dish that shows a woman plucking a flower. The round dish, she explains, represents the moon, and the woman standing at its center is Chang'e, the moon goddess in Chinese folklore. The flower, she says, could have to do with success at an imperial examination, a process that was called "picking flowers" at the time. Later, Chen pulls out a dish decorated with the figure of a woman with a bouffant hairdo. "Her hair looks like a flower," Chen says. "This was fashionable among royal women during the late Ming Dynasty." The subjects on the porcelain are so characteristically Chinese that Chen suspects they were intended for other Asian markets, such as Japan or the Philippines.

In addition to its porcelain, Nan'ao Number One stands out for its weaponry, bronze cannons. Xiamen University's Wu told Archaeology, "This is the first boat found with cannons on board," he says. They could have been used to protect the smugglers from imperial forces. "They would confiscate your goods, put you in jail, and sink your ship---the stakes were high." The cannons could also have served to protect the boat against other pirates or raiders. The sailors might also have feared becoming entangled in the intermittent battles that occurred between the Dutch and Portuguese through the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth.

Other Chinese Shipwrecks

Lauren Hilgers wrote in Archaeology magazine: The English treasure hunter Michael Hatcher was a key figure in getting Chinese underwater archeology going. His biggest find, which came to be known as the Nanking Cargo, came in the 1980s. It was the wreck of a Dutch ship that had run afoul of a coral reef near Indonesia in 1752, dropping a load of tea, gold, and more than 150,000 pieces of Ming Dynasty porcelain. "The porcelain was all from Jingdezhen, near Nanjing," says Wu. "That boat wasn't Chinese, but all that porcelain originated from China." China's government did its best to stop the sale of what it saw as national cultural heritage, but Hatcher was still able to auction off the bulk of his find in 1986, reportedly earning more than $20 million. [Source: Lauren Hilgers, Archaeology, September/October 2011]

In 2001, Cui was sent to head excavations at Nanhai Number One, the wreck of a Song Dynasty boat that sailed well before the dismantling of China's fleet during the Ming Dynasty. "[The Song Dynasty] was a time when China's sailing fleet was well developed," Cui says. "Chinese boats were making it all the way to India and Africa." The boat was discovered by accident in 1987 by a team of English and Chinese researchers who were searching for an English boat thought to have gone down in the area. The Chinese archaeologists, however, weren't prepared to take on the large and complicated excavation.

"The Nanhai was in shallower water than the Nan'ao, but the visibility was terrible," Cui says. "We would have had to conduct excavations by feeling our way along the bottom of the sea floor." In 2001, archaeologists revisited the wreck with a bigger budget---$20.3 million---which was used to build a custom saltwater tank on Hailing Island in Guangdong, part of a new Maritime Silk Road Museum, which opened in 2009. Archaeologists actually lifted the boat---along with the silt in which it was buried---out of the ocean and into the tank for study. The spectacle of a 3,000-ton steel cage being pulled out of the water earned shipwrecks a place in China's popular consciousness.

Image Sources: Marion Kaplan, Nabataea.com, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021