REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO

Suharto became progressively more rigid, authoritarian and corrupt during his decades in power. Amnesty International said in a report that Indonesia was a country ruled with an iron rod, where dissidence is punished by imprisonment, torture and death." Amnesty International said that one of it investigators met with three Indonesian men who were tortured with electric shocks for releasing balloons with pro-democracy messages inside. Travel writer Norman Lewis wrote: "Keep profile low. In Indonesia that is the golden rule."

After Suharto took power he banned all but two newspapers and often it seemed like their job was to depict the Communist Party as villains. He closed down publications critical of his government and family and thumbed his nose at freedom of the press. He outlawed true opposition parties and brutally cracked down on dissent and limited freedom of speech and undermined rivals using rumors and disinformation.

In the early 1990s, political openness was increasingly embraced by political and labor organizations. In 1990, a group of prominent Indonesians publicly demanded that Suharto retire from the presidency at the end of his term. In 1991, labor unrest increased, and the army was called in to quell a rash of strikes. Government efforts to raise funds through a state lottery were opposed and ultimately prohibited on religious grounds when the country's highest Islamic authority deemed the lottery haram, or forbidden. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

RELATED ARTICLES:

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

Challenges to the Suharto Regime

Underlying these New Order initiatives for political and economic change was an important but largely undiscussed continuity in some fundamental ideas about the nature of both the nation and the state. Consistent with the ideas of the founders of independent Indonesia, New Order architects viewed the state as necessarily unitary and powerful, having little patience with notions of federalism or decentralization of powers. Indeed, civilian and military leaders alike appear to have assumed that only this highly centric form of state authority could bring about the political stability and economic growth they sought. The same leaders also inherited assumptions about the extent and unity of a national territory generally accepted as comprising the former Netherlands East Indies and did not find other suggestions tolerable. [Source: Library of Congress *]

These convictions led among other things to raising an enlarged, more centralized bureaucratic structure for the New Order state, and requiring administrative authorities to apply centrally developed policies on matters ranging from taxes to traditional performances, education to elections, firmly and uniformly throughout the nation. Seen from the government perspective, the effort represented a rational, modern approach, while to critics it often appeared narrow, oppressive, and self-serving. Resentment and debate, as well as legal and physical struggles, over such issues were a regular feature of life under New Order governance. *

Voices of democratic opposition were heard May 5, 1980, when a group called the Petition of Fifty, composed of former generals, political leaders, academicians, students, and others, called for greater political freedom. In 1984 the group accused Suharto of attempting to establish a one-party state through his Pancasila policy. In the wake of the 1984-85 violence, one of the Petition of Fifty's leaders, Lieutenant General H.R. Dharsono, who had served as secretary general of ASEAN, was put on trial for antigovernment activities and sentenced to a ten-year jail term (from which he was released in 1990). *

Not all regions welcomed incorporation into the Indonesian republic. Aceh in northern Sumatra, several eastern islands, and Christian communities in the Ambon and Maluku Islands resisted what they viewed as Javanese domination. In 1969, the United Nations controversially transferred the western half of New Guinea from Dutch control to Indonesia, where it became Irian Jaya—sparking ongoing independence movements. Following Portugal’s withdrawal from East Timor in 1974, Indonesia invaded in 1975 with American encouragement amid post–Vietnam War fears of communism. Though Indonesia introduced roads, schools, and administrative structures, its occupation was marked by harsh repression and heavy loss of life. When East Timor finally voted for independence in 1999—after Suharto’s fall—Indonesian forces and militias destroyed much of the territory in a retaliatory scorched-earth campaign. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

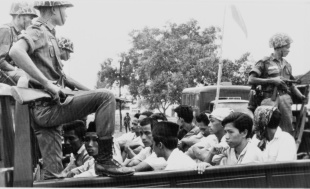

Crackdowns and Violence Under the Suharto Regime

Ellen Nakashima wrote in the Washington Post: “From 1965 to 1971, perhaps half a million people were killed during the dictatorship of Gen. Suharto, who governed the country for three decades. Hundreds of thousands more were imprisoned in a purge of supposed communists and leftists. No independent investigation has ever been conducted; no one has been held to account. Indonesian officials have been loath to face the past. The survivors, emboldened by the end of the Suharto dictatorship in 1998, have only recently begun breaking their silence to set history straight. They want the world to know about the mass killings and to get Indonesia to face its past. [Source: Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post Foreign Service, October 30, 2005]

To maintain power Suharto employed a divide and rule strategy and never gave anything away to keep his enemies off guard. Ethnic, religious and regional divisions were kept under wraps— but simmering below the surface—through repression not negotiation. According to The Guardian: “Suharto survived the growth of discontent through the ruthless use of an intelligence apparatus. Muslim militants were jailed and social protest suppressed. More subtly, the older politicians whom he had supplanted were allowed to form an ineffective "group of 50" in 1980.”

Suharto ordered the invasion of East Timor in 1975. A massacre in November 1991 led to international condemnation of Indonesia's policies in East Timor. Also brutal but less visible were crack downs in Aceh and Irian Jaya. See East Timor, Aceh and Papua.

See Separate Articles: VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

Political Prisoners and Death Squad Under Suharto

Political prisoners were imprisoned without charges or trials and sent off to Gulag-like prison camps, where many were executed or died from starvation. Outside the prisons family members of prisoners were harassed, humiliated and persecuted. Denied even the simplest tools, the prisoners were forced to clear land with their bare hands. In some cases prisoners were denied books and cigarettes out of concern that the paper used to make them might be used for the paper to right messages.

As of 1975, ten years after the 1965 coup, the Indonesian government still held 70,000 political prisoners, most of whom never were given a trial. Even after the were released many were not allowed to return to their homes, They were forced t live in “transmigration camps that were not much better than the prison camps they had previously been in.

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: Scholars have estimated that as many as 750,000 people were arrested in the military crackdown after the killing of the generals, and that 55,000 to 100,000 people accused of being Communists may have been held without trial for as long as 14 years. In the early ’80s, 4,000 to 9,000 people were killed by death squads organized by army Special Forces to deal with petty criminals and some political operatives. And, according to Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson, a professor emeritus of government at Cornell, 200,000 people of a population of 700,000 died in East Timor in the civil war and famine after Indonesia’s invasion and annexation in 1975. Professor Anderson called Mr. Suharto a “malign dictator with blood on his hands over the years anywhere from half a million to a million people.” [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

Massacre at the Rat Hole in Lorejo in 1968

Reporting from Lorejo, Ellen Nakashima wrote in the Washington Post: “An old man, thin and stooped, raised a wooden stick over his head and swung it down with both hands. This, he said, was how he executed fellow villagers, striking their necks with an iron bar. The kneeling victims, tied together by their thumbs, tumbled two by two into a hole, now a mass grave. "I was ordered to kill these people by the army," said Katirin, 75. "If I refused, they would shoot me. . . . I was so afraid, I just did it." As Katirin demonstrated how he executed people in the 1960s, a widow, Supiyem, watched silently, her eyes cold. Her husband was among those slain on this remote hill at the eastern end of the Indonesian island of Java. For Katirin, the killer, it apparently was a gesture of atonement. Many victims were peasants like Supiyem's husband, Duryadi, who knew little of Marx or Mao. [Source: Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post Foreign Service, October 30, 2005 /+]

“Katirin is one of the few living witnesses to the 1968 massacre of at least 100 villagers over several weeks at the Rat Hole, in the woods of Lorejo village. The unmarked mass grave is among hundreds of stony, muddy and watery tombs. Katirin estimated that he killed 10 people (he had previously told a researcher he killed dozens), but none was Supiyem's husband, whose murder left Supiyem a widow with an infant son, Pujianto or "Puput.'' Supiyem said that Katirin's role in the killings disgusted her but that she did not hold him accountable. She blames the Indonesian army and the Suharto regime, who bade villagers like Katirin to do their dirty work. /+\

“Suharto and his successors have never acknowledged the army's involvement in the massacres. The killings here in south Blitar, were part of state-sanctioned brutality against people in thousands of villages across Indonesia, said Albertus Suryo Wicaksono, a researcher who in 2002 spent one week excavating Luweng Tikus. The 1968 massacre here was part of a four-month army campaign ordered by Suharto to finish off the party. No one knows the overall death toll from the purges — guesses range from 300,000 to more than 1 million, but the most credible estimate, several academics said, is 500,000. /+\

“Supiyem had been married only one year when, in August 1968, her husband was killed. Duryadi, a rice farmer, belonged to a farmers group that supported the Communist land reform program. Two of Supiyem's younger brothers were arrested and marched away, never to return. A third brother was detained and released, by his count, 11 times that year. To save that brother from death, she recalled, she forced herself to serve as "a wife" for the new village head. For seven years, she said, she endured Sarmin, who moved in with her at her parents' house. She cooked and cleaned for him. She slept with him. "I shut down my feelings," she said, staring into the distance. "It was unthinkable." Sarmin left the village in 1975, when his term ended, she said. He died in the late 1990s. /+\

Massacre in Tanjung Priok in 1984

The Pancasila policy aroused strong opposition among politically active Muslims. Riots broke out in the Tanjung Priok port area of Jakarta on September 12, 1984, and a wave of bombings and arson took place in 1985. Targets included the Borobudur Buddhist temple, the palace of the Sunan of Surakarta, commercial districts in Jakarta, and the headquarters of the Indonesian state radio. *

In 1984 in Tanjung Priok, soldiers opened fire on a group of demonstrators protesting the detainment of four Muslim men. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, were killed. A leader of the demonstration later told the Washington Post, “There was no warning.” He said he was shot in the ankle and one man to his right and three men to his left were killed by bullets. He said he played dead and was loaded onto a truck with at least a dozen corpses.

Another leader told the Washington Post that he heard about the protest while attending a prayer session at a local mosque. He carried a green banner with an Islamic slogan written on it. He said the crowds was several thousand strong. They advanced towards a local military headquarters and were met by a large government military unit with their guns drawn and baronets pointed at the protestors.

After initially opening fire, the soldiers began hunting down survivors. The man carrying the green banner said he was hit in the chest and right arm. One soldier, he said, came up to him. “He shouted, ‘This one’s still alive!’ He tried to shoot me once. the bullet came very close to my head but missed. He also played dead and was loaded on a truck piled with corpses, in this case four deep. “It was impossible for me to count the number of bodies because of the conditions and the fear and the pain.”

Buru Island Humanitarian Project

Under Suharto, some 12,000 political prisoners were sent to the Buru island in eastern Spice Island to the "Humanitarian Project" there, where dissidents, suspected communist, sympathizers, lawyers, professors, doctors and "the shining light of Indonesia's intelligencia" toiled in the hot sun. Many died from torture, gun shot wounds from guards, blows from falling trees, spear wounds from local residents, starvation, malaria, filariasis (a mosquito-born disease that produced elephantiasis) hepatitis, tuberculosis and other diseases.

Described as a tropical Siberian gulag, the Buru Island Humanitarian Center was established in 1969. It consisted of camps built around wooden barracks that housed 50 prisoners each. The prisoners grew corn and rice, felled trees, built roads, cultivated the land, and constructed buildings. Many of the prisoners were detained for more than a decade without being charged or given a trial.

After initially being detained on the island of Nusa Kembangan, off the south Java coast, the prominent Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer was moved, along with thousands of other political prisoners, to Buru. Pramoedya was in prison from 1965 to 1979. Twelve of those years were spent on Buru Island. "Everyone here has been tortured," he said. "I was beaten first by my non-comm and then by the colonel himself. I had gone into the woods one day without permission. The colonel punched me in the stomach and hit me on the head."

Prisoners were prohibited from having reading material and those found possessing a book or a magazine risked being tortured or severely punished or even executed. On one occasion, Pramoedya said, a man found some scraps of newspaper while unwrapping something. Three day later he was found dead in a river with his hands tied behind his back.

Banned from possessing paper or a pen during his first years at Buru, Pramoedya wrote the historical novels for which he is famous in his head, offering installments each day to his fellow prisoners who helped him remember and get his facts straight. Eventually a sympathetic general allowed him to have pen and paper and, later, a typewriter. To win these favors he used money he earned from selling duck eggs.

John Aglionby wrote in The Guardian, “ ”The scale of the suffering on Buru island eventually came to light through The Mute's Soliloquy, an autobiographical work published decades later - and in English in 1999 - with numerous incidents recorded on scraps of paper that were smuggled out by a sympathetic Catholic priest. Most of the prisoners, including Pramoedya, were moved from Buru in 1979, but the writer was only released as a result of intensive lobbying by numerous foreign diplomats. He was confined to Jakarta until 1992.[Source: John Aglionby, The Guardian, May 3, 2006]

Suharto and West Papua

Inherited sensitivity to potential challenges to national unity also led to military involvement—and long-term enmities—in several corners of the archipelago. The first of these took place in West New Guinea (later called Irian Jaya, now the provinces of Papua and Papua Barat). During the 1949 Round Table Conference, the Dutch had refused to discuss the status of this territory, which, upon recognition of Indonesian independence, was still unresolved. Conflict over the issue escalated during the early 1960s, as the Dutch prepared to declare a separate state, and Sukarno responded with a military campaign. In August 1962, the Dutch were pressed by world opinion to turn over West New Guinea to the UN, which permitted Indonesia to administer the territory for a five-year period until an unspecified “Act of Free Choice” could be held. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Thus it fell to the New Order to complete a project begun by the Old Order. Ali Murtopo—with the military support of troops commanded by Sarwo Edhie Wibowo (1927–89)—arranged the campaign that, in mid-1969, produced a consensus among more than 1,000 designated local leaders in favor of integration with the Indonesian state. This decision was soon approved by the UN, and the territory became Indonesia’s twenty-sixth province before the end of the year. The integration process did not go unopposed, however. Initial bitterness came from Papuans who had stood to benefit from a Dutch-sponsored independence and who formed the Free Papua Organization (OPM) in 1965. But resentment soon spread because of Jakarta’s placement of thousands of troops and officials in the territory, exploitation of natural resources (for example, by signing contracts for mining rights with the U.S. corporation Freeport-McMoRan Copper and Gold in 1967), encouragement of settlers from Java and elsewhere, and interference with local traditions such as dress and religious beliefs. OPM leaders declared Papua’s secession in 1971 and began a guerrilla resistance. Despite internal splits, OPM resistance continued throughout the New Order era, peaking in the mid-1980s and again in the mid-1990s, attracting a significant ABRI presence. *

Suharto and Aceh

In Aceh, northern Sumatra, resistance to Jakarta’s extension of authority arose in the mid-1970s. This area, known for its 30-year struggle against Dutch rule in the nineteenth century, had also found it necessary to fight for its autonomy after independence, in a movement led by the Muslim political figure Muhammad Daud Beureueh (1899–1987) and affiliated with Darul Islam. Aceh won status as a separate province in 1957 and as a semiautonomous special territory with greater local control of religious matters in 1959.

In the early 1970s, however, the discovery of natural gas in Lhokseumawe, Aceh, and the fact that this location could be more readily developed than other deposits found in eastern Kalimantan and the Natuna Islands, meant that for Jakarta Acehnese autonomy was now less tolerable. By 1976 armed resistance to the central government began under the banner of a Free Aceh Movement (GAM), led by Hasan di Tiro (1925–2010), a former Darul Islam leader who claimed descent from a hero of the 1873–1903 Aceh war against the Dutch. Jakarta responded with limited military force that crushed the small movement, but a decade later, when GAM reappeared with greater local support and funding from Libya and Iran, both the movement and the Jakarta response were far more extensive and brutal: estimates were of between 2,000 and 10,000 deaths, mostly civilian. In the mid-1990s, Jakarta claimed to have defeated GAM’s guerrilla forces, but resentment ran deep, and thousands of government troops remained posted in Aceh.

Suharto and East Timor

The military involvement of greatest significance during the New Order, however, was that in East Timor. In 1975–76, Indonesia invaded and annexed East Timor, a former Portuguese colony, incorporating it as a province. The United Nations refused to recognize the takeover. Armed resistance by separatists in the predominantly Roman Catholic territory continued for years, resulting in heavy casualties and drawing growing criticism from the United States and international human-rights organizations.

The status of East Timor changed when a radically new, democratic government came to power in Lisbon in 1974, and Portugal soon decided to shed its colonial holdings. Local political parties quickly formed in favor of different visions of the future, the most prominent being the leftist Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin), and the Timorese Popular Democratic Association (Apodeti), which sought integration with Indonesia as a semi-autonomous province. [Source: Library of Congress *]

After Portugal withdrew from East Timor, a struggle erupted among competing political groups, most prominently the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin). By mid-1975, it appeared that Fretilin would be the likely winner in an upcoming general election, a prospect that brought internal political violence as well as escalating concern in Jakarta that a “communist” government (a designation generally considered inaccurate) might plant itself in the midst of the Indonesian nation. On November 28, 1975, Fretilin announced the independence of the Democratic Republic of East Timor (as of 2002, the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste), which it controlled. Driven by ideological fears rather than a desire for national expansion, Jakarta reversed its earlier avowed policy of noninterference and, with the implicit consent of Australia and the United States, on December 7 launched an assault on East Timor and soon began a brutal “pacification” requiring more than 30,000 ABRI troops. On July 15, 1976, East Timor, as Timor Timur, became the twenty-seventh province of Indonesia, and Jakarta began both exploiting the limited natural resources—coffee, sandalwood, marble, and prospects for vanilla and oil—and undertaking rebuilding and development programs. *

In the late 1980s, the province opened to foreign observers, and in 1990 ABRI finally captured the charismatic Fretilin leader José Alexandre “Xanana” Gusmão (born 1946), but widespread resentment of the occupation festered. Then, in November 1991, Indonesian soldiers fired on a crowd of demonstrators at the Santa Cruz Cemetery in Dili, the capital, and dramatic video footage of this event, in which between 50 and 250 civilians were killed, was distributed worldwide. The majority of Indonesians knew and cared little about East Timor and had not basically disagreed with New Order policies there, but the outside world felt very differently. Indonesia found itself increasingly pressured—for example, by the United States, the European Union (EU), the Roman Catholic Church, and the UN—to change course. Indonesia resisted, and, indeed, military pressures in East Timor tightened, and Muslim migration, especially from Java, increased rapidly in this largely Catholic and animist area. Not surprisingly, indigenous opposition increased, especially among a younger generation born in the 1970s. Jakarta did not recognize this response as either legitimate protest or nascent nationalism, which it had unwittingly done much to foster. *

See Separate Articles Under EAST TIMOR HISTORY: factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025