WHEN AND HOW THE FIRST HUMANS CAME TO AMERICA

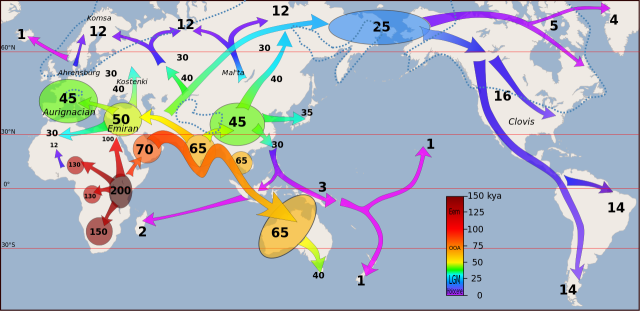

Archaeologists have long debated when and how the first people made it to North America from Asia. Researchers previously thought early humans crossed the Bering land bridge from Siberia to Canada 13,000 years ago. But fairly recently pretty strong evidence has appeared that the arrived between 23,000 and 30,000 years ago, reaching New Mexico by at least 21,000 years ago. [Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, July 23, 2020]

If the first Americans did indeed arrive at that time they didn't cross the Bering Land Bridge The land bridge at the Bering Strait was impassable at that time, so the research suggests the first Americans had to have arrived by sea. In a July 2020 paper published in Nature, two archaeologists looked at artifacts and traces of human occupation from 42 sites across North America. By dating those findings, the researchers modeled how and when people dispersed across the continent. They concluded that humans were "probably present before, during, and immediately after the Last Glacial Maximum" — that's the peak of the last ice age, which occurred between 26,500 and 19,000 years ago.

If humans were on the continent before or during the peak of the last ice age, they could not have come via the Bering Land Bridge, since it would have been partially submerged or blocked by impenetrable ice sheets. “Just because the bridge is considered a standard entry doesn't mean it's the only one," Archaeologist Ciprian Ardelean told Business Insider. adding, "the panorama of human arrivals during the Last Glacial Maximum is much more complex than we thought."

“Lorena Becerra-Valdivia, an archaeological scientist at the Universities of Oxford and New South Wales and the lead author of the paper, told Business Insider that "the new findings suggest that humans likely took a coastal route." “That means they were probably seafarers who arrived by boat, possibly from modern-day Russia or Japan. Then they expanded south by sailing down the Pacific Coast.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF HUMANS TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE FIRST HUMANS IN AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

SINGLE WAVE VS MULTIPLE PULSE THEORY AND MIGRATION OF EARLY PEOPLE TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST AMERICANS: DNA, ASIA AND ASIANS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN WHAT IS NOW ALASKA AND CANADA factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN WHAT IS NOW THE CONTINENTAL U.S. factsanddetails.com ;

WHITE SANDS 23,000-21,000 YEAR-OLD HUMAN FOOTPRINTS factsanddetails.com ;

CLOVIS PEOPLE: SITES, POINTS, PRE-CLOVIS, MAMMOTHS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHERN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST HUMANS AND SETTLEMENTS IN THE AMAZON factsanddetails.com ;

SOLUTREAN HYPOTHESIS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas” By Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas (Twelve, 2022); Amazon.com;

“First Peoples in a New World: Populating Ice Age America” by David J. Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, (Cambridge University Press, 2021); Amazon.com;

“The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere” by Paulette F. C. Steeves (2023) Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

"The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory" by Thomas D. Dillehay ( Basic Books, 2000 Dated) Amazon.com;

”Strangers in a New Land: What Archaeology Reveals About the First Americans”

by J. M. Adovasio, David Pedler (2016) Amazon.com;

“Paleoindian Mammoth and Mastodon Kill Sites of North America by Jason Pentrail (2021) Amazon.com;

“Clovis The First Americans?: by F. Scott Crawford (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture”

by Dennis J. J. Stanford, Bruce A. Bradley, Michael Collins Amazon.com;

“From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic—Paleo-Indian Adaptations (Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology) by Olga Soffer (1993) Amazon.com;

When Did the First Humans Come to America

Map of Beringia with exposed seafloor and glaciation at 40,000 years ago and 16,000 years ago; The green arrow shows "interior migration" model via ice-free corrido; the red arrow indicates the "coastal migration" model, both leading to a "rapid colonization" of the Americas after c 16,000 years ago

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “About 100,000 years ago, modern human beings started spreading out from their initial homeland in Africa to occupy Europe, Asia and, by sea, even Australia, displacing or absorbing Neanderthals and other archaic hominin species. That diaspora took about 70,000 years, and when it was completed our ancestors stood triumphant. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013 /||]

“The peopling of the Americas, scholars tend to agree, happened sometime in the past 25,000 years. In what might be called the standard view of events, a wave of big game hunters crossed into the New World from Siberia at the end of the last ice age, when the Bering Strait was a land bridge that had emerged after glaciers and continental ice sheets froze enough of the world’s water to lower sea level as much as 400 feet below what it is today. /||\

“The key question is precisely when the migration occurred. To be sure, there were constraints imposed by North America’s glacial history. Researchers suggest that it happened sometime after gradual warming began 25,000 years ago during the depths of the ice age, but well before a severe cold snap reversed the trend 12,900 years ago. Early in this window, when the weather was very cold, migration by boat was more likely because immense expanses of ice would have turned an overland journey into a nightmarish ordeal. Later, however, the ice receded, opening up plausible land bridges for trekkers coming across the Bering Strait. /||\

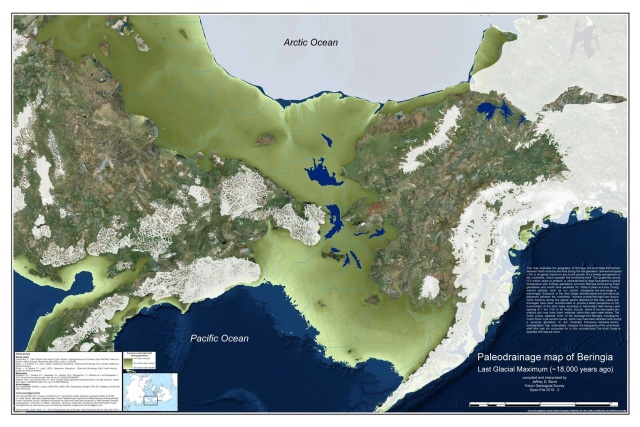

John Hoffecker, a research fellow emeritus of early human history at the University of Colorado Boulder, has said recent evidence has shown "beyond a reasonable doubt" that the Bering Land Bridge first emerged around 35,700 years ago before disappearing again about 12,000 years ago, near the end of the last ice age, when glaciers melted and sea level began to rise. At times, the bridge would have resembled the tundra of northern Alaska and Siberia and been home to large mammals, Hoffecker said. But often it wasn’t like that. Recent research on the region's paleoclimate posits that the bridge was often locked up in impassable ice except during brief windows from 24,500 to 22,000 years ago and 16,400 to 14,800 years ago.[Source: Amanda Heidt, Live Science, December 30, 2023]

Beringia

Almost all scientists agree, that the first Americans arrived via Beringia — a now-submerged, landmass that connected what is now Alaska and the Russian Far East. During the peak glaciation of the last ice age, when much of Earth's water was frozen in ice sheets, ocean levels fell. fall. Beringia emerged when waters in the North Pacific dropped roughly 50 meters (164 feet) below today's levels; At one time Beringia was 1,800-kilometers (1,100-mile) wide a could have been traversed on foot but was also often covered by large glaciers that would have made such travel difficult. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

Beringia includes parts of Russia, known as western Beringia; Alaska, called eastern Beringia; and the ancient land bridge that connected the two. According to a study published February 6, 2023 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the land bridge between Russia and Alaska existed for two relatively brief periods. The first period lasted from 24,500 to 22,000 years ago, and the other spanned lasted 16,400 to 14,800 years ago.

A digital map created in 2019 by Jeffrey Bond, who studies the geology of ice age sediments at the Yukon Geological Survey in Canada, revealed what the landscape of Beringia was likely like about 18,000 years ago. Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science; At 18,000 years ago, Beringia was a relatively cold and dry place, with little tree cover. But it was still speckled with rivers and streams. Bond's map shows that it likely had a number of large lakes. "Grasslands, shrubs and tundra-like conditions would have prevailed in many places," Bond said. These environments helped megafauna — animals heavier than 100 lbs. (45 kilograms) — thrive, including the woolly mammoth, Beringian lion, short-faced bear, grizzly bear, muskox, steppe bison, American scimitar cat, caribou, Yukon horse, saiga antelope, gray wolf and giant beaver, according to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, February 16, 2019]

This vast, open region allowed megafauna and early humans to live off the land, said. Julie Brigham-Grette, a professor and department head of geosciences at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. However, it's still a mystery exactly when humans began crossing the land bridge. Genetic studies show that the first humans to cross became genetically isolated from people in East Asia between about 25,000 to 20,000 years ago. And archaeological evidence shows that people reached the Yukon at least 14,000 years ago, Bond said. But it's still unclear how long it took the first Americans to cross the bridge and what route they took. "The fact that this land bridge was repeatedly exposed and flooded and exposed and flooded over the past 3 million years is really interesting because Beringia, at its largest extent, was really a high latitude continental landscape in its own right," Brigham-Grette said. Now that the Bering Strait is filled with water, it's a gateway linking the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans through the Arctic Basin. "There are few places like it on our planet that have such a complex paleo geography," Brigham-Grette said.

Did the First Americans Come from China Beginning Over 20,000 Years Ago?

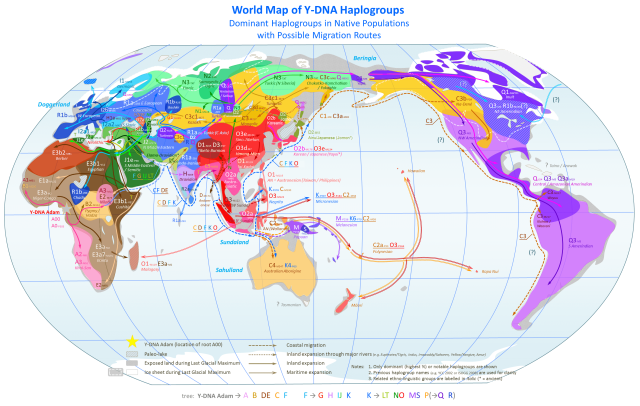

A DNA study published in May 2023 in Cell Reports revealed that some of the first arrivals in America came from China during two distinct migrations: the first during the last ice age, and the second shortly after. "Our findings indicate that besides the previously indicated ancestral sources of Native Americans in Siberia, the northern coastal China also served as a genetic reservoir contributing to the gene pool," Yu-Chun Li, one of the report authors, told AFP. [Source: Issam Ahmed, AFP, May 10, 2023]

AFP reported: Li added that during the second migration, the same lineage of people settled in Japan, which could help explain similarities in prehistoric arrowheads and spears found in the Americas, China and Japan. It was once believed that ancient Siberians, who crossed over a land bridge that existed in the Bering Strait linking modern Russia and Alaska, were the sole ancestors of Native Americans. More recent research, from the late 2000s onwards, has signaled more diverse sources from Asia could be connected to an ancient lineage responsible for founding populations across the Americas, including Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico and California. Known as D4h, this lineage is found in mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from mothers and is used to trace maternal ancestry.

The team from the Kunming Institute of Zoology embarked on a ten-year hunt for D4h, combing through 100,000 modern and 15,000 ancient DNA samples across Eurasia. They eventually landed on 216 contemporary and 39 ancient individuals who came from the ancient lineage. Li said a strength of the study was the number of samples they discovered, and complementary evidence from Y chromosomal DNA showing male ancestors of Native Americans lived in northern China at the same time as the female ancestors, made them confident of their findings.Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis who did not take part in this research, told Live Science while the new study is exciting, it's just "another piece of the puzzle," on how and when ice age humans first populated the Americas, Davis said. For instance, the researchers stressed that while these new findings suggest this single northern Chinese lineage may have contributed to Indigenous American ancestry, "it does not represent the whole history of all Native Americans," Li said. "Investigating other lineages showing genetic connections between Asia and the Americas will help obtain the whole picture of the history of Native Americans."

Did the First Americans Come from China in Two Waves?

AFP reported: By analyzing the mutations that had accrued over time, looking at the samples' geographic locations and using carbon dating, the team from Kunming described above were able to reconstruct the D4h lineage's origins and expansion history. The results revealed two migration events. The first was between 19,500 and 26,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheet coverage was at its greatest and climate conditions in northern China were likely inhospitable. The second occurred during the melting period, between 19,000 and 11,500 years ago. Increasing human populations during this period might have triggered migrations. In both cases, the scientists think the travelers were seafarers who docked in America and traveled along the Pacific coast by boats. This is because a grassy passageway between two ice sheets in modern Canada, known as the "inland ice-free corridor," was not yet opened. [Source: Issam Ahmed, AFP, May 10, 2023]

In the second migration, a subgroup branched out from northern coastal China to Japan, contributing to the Japanese people, especially the indigenous Ainu, the study said, a finding that chimes with archeological similarities between ancient people in the Americas, China and Japan. Li said a strength of the study was the number of samples they discovered, and complementary evidence from Y chromosomal DNA showing male ancestors of Native Americans lived in northern China at the same time as the female ancestors, made them confident of their findings. "However, we don't know in which specific place in northern coastal China this expansion occurred and what specific events promoted these migrations," he said. "More evidence, especially ancient genomes, are needed to answer these questions."

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: Both diasporas apparently occurred when the land bridge from Asia to the Americas was obstructed by ice, so the researchers suggest that ice age people may have traveled via the Pacific coast instead.The first migration likely happened between 19,500 and 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, the coldest part of the last ice age, the researchers said. Back then, ice sheets covered much of the planet, and living in northern China would have likely proven difficult for humans. The scientists estimated the second event apparently occurred between 19,000 and 11,500 years ago, when the ice sheets began melting. Prior work suggested this climate shift likely helped support the rapid growth seen in human populations during this era, which may have helped drive their spread into other regions.[Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science May 10, 2023]

The researchers discovered that during the second wave, one lineage branched out from northern coastal China and traveled to Japan, where they contributed to the Japanese gene pool, especially the indigenous Ainu people. "This points to an unexpected genetic link between Native Americans and the Japanese," Kong said. In all, the new study "matches well with what we know about the archaeological record of Japan, and lends weight to current models of how humans came to populate the Americas,"Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis who did not take part in this research, told Live Science.

This discovery may help explain some archeological similarities that prior work controversially suggested at times existed between Stone Age peoples in China, Japan and the Americas. Specifically, researchers had argued the three regions possessed similarities in how they crafted "stemmed projectile points" for arrowheads and spears.

Data from 42 Sites in Beringia Suggests an Arrival Date After 26,000 Years Ago

In a study published online on July 22, 2022 in the journal Nature, archaeologists took already-published dates from 42 archaeological sites in North America and Beringia (the region that historically connected Russia and America) and plugged the data into a model that analyzed human dispersal. This model found an early human presence in North American dating to at least 26,000 years ago. According to Live Science: In particular, the researchers were interested when humans first began occupying each site, "since people are present in a region before an archaeological site is created," said study lead researcher Lorena Becerra Valdivia, an archaeological scientist at the University of Oxford in England and the University of New South Wales in Australia. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 23, 2020]

"It is reasonable to assume, for example, that there were people in North America before we see their trace in Mexico at Chiquihuite Cave," Becerra Valdivia told Live Science. "In this way, our study was to identify large-scale patterns of human migration into and through the continent over time."

After analyzing data from 42 archaeological sites across the continent, the researchers found that "whilst there were humans in North America before, during and immediately after the Last Glacial Maximum, populations expanded significantly across the continent much later, during a period of abrupt global climate warming at the end of the Ice Age, beginning at around 14,700 years ago," said Becerra Valdivia, who was also a co-researcher on the Chiquihuite Cave study.

This analysis is based on the fact that three major stone tool traditions — the Clovis, Western Stemmed and Beringian — all began at about the same time, as well as genetic evidence that points to a population spike. This population growth likely played a role in the decline of large animals such as mammoths and camels, although climate change at the end of the last ice age likely contributed too, she said. "It seems, therefore, that the initial arrivals did not have a marked, immediate impact in megafaunal decline," Becerra Valdivia said. "Population expansion and growth later on were key."

She acknowledged that because this study focuses only on North American, similar research on South America is needed. "Only by unlocking the history of initial human occupation there [in South America] will we be able to see the entire picture and understand the full migration pattern," Becerra Valdivia said.

This statistical modeling does make some assumptions about occupation dates, "making their conclusions more open to interpretation and debate," Harcourt-Smith said. However, it also shows "that if we take a total evidence approach to the first occupation of the Americas, the data suggest (only suggest) that humans may have been around as far back as 30,000 years ago, which is extraordinary," Harcourt-Smith said. "Obviously, we'll need hard evidence [such as human remains or DNA] to back up this suggestion, but it's exciting to think about."

Clovis People and Clovis Theory

According to Live Science: In the 1920s and 1930s, Western archaeologists discovered sharp-edged, leaf-shaped stone spear points near Clovis, New Mexico. The people who made them, now dubbed the Clovis people, lived in North America between 13,000 and 12,700 years ago, based on a 2020 analysis of bone, charcoal and plant remains found at Clovis sites. At the time, it was thought that the Clovis traveled across Beringia and then moved through an ice-free corridor, or "a gap between the continental ice sheets," in what is now part of Alaska and Canada. "Once they exited, they spread quickly throughout the Americas, bearing a signature stone tool known as the Clovis spear point," which was likely used to hunt megafauna, such as mammoths and bison, as well as smaller game. For decades, it was challenging to suggest the first Americans arrived any earlier than 13,000 years ago. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: For decades the most compelling evidence for the standard view that first people arrived in America around 13,000 to 14,000 years ago consisted of distinctive, exquisitely crafted, grooved bifacial projectile points, called “Clovis points” after the New Mexico town near where they were first discovered in 1929. With the aid of radiocarbon dating in the 1950s, archaeologists determined that the Clovis sites were 13,500 years old. This came as little surprise, for the first Clovis points were found in ancient campsites along with the remains of mammoth and ice age bison, creatures that researchers knew had died out thousands of years ago. But the discovery dramatically undermined the prevailing wisdom that human beings and these ice age “megafauna” did not exist in America at the same time. Scholars flocked to New Mexico to see for themselves. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013 /||]

“The idea that the Clovis people, as they came to be known, were the first Americans quickly won over the research community. “The evidence was unequivocal,” said Ted Goebel, a colleague of Waters at the Center for the Study of the First Americans. Clovis sites, it turned out, were spread all over the continent, and “there was a clear association of the fauna with hundreds, if not thousands, of artifacts,” Goebel said. “Again and again it was the full picture.” /||\

“Furthermore, the earliest Clovis dates corresponded roughly to the right geological moment—after the ice age warming, before the great cold snap. The northern ice had receded far enough so incoming settlers could curl around to the eastern slope of North America’s coastal mountains and hike south along an ice-free corridor between the cordilleran mountain glaciers to the west and the huge Laurentide ice sheet that swaddled much of Canada to the east. “It was a very nice package, and that’s what sealed the deal,” Goebel said. “Clovis as the first Americans became the standard, and it’s really a high bar.” /||\

“When they reached the temperate prairies, the migrants found an environment far different from what we know today—both fantastic and terrifying. There were mammoths, mastodons, giant sloths, camels, bison, lions, saber-toothed cats, cheetahs, dire wolves weighing 150 pounds, eight-foot beavers and short-faced bears that stood more than six feet tall on all fours and weighed 1,800 pounds. Clovis points, finely made and strong, were well suited for hunting large animals. /||\

“The hunters spread through the United States and Mexico, the story went, pursuing prey until too few animals remained to support them in the last cold snap. Radiocarbon dates show that most of the megafauna became extinct around 12,700 years ago. The Clovis points disappeared then as well, perhaps because there were no longer any large animals to hunt. The Clovis theory, over time, acquired the force of dogma. “We all learned it as undergraduates,” Waters recalled. Any artifacts that scholars said came before Clovis, or competing theories that cast doubt on the Clovis-first idea, were ridiculed by the archaeological establishment, discredited as bad science or ignored.” /||\

See Separate Article: CLOVIS PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

Early human sites in North America

Land Bridge Theory

Land Bridge Theory was closely tied to Clovis First Theory. According to the Clovis First theory, people crossed from Siberia into North America around 13,500 years ago via the Bering Land Bridge — a mass of land that emerged when the last ice age lowered sea levels — and spread across the Americas. After the first people arrived in Alaska, the theory went, they followed an “ice-free corridor” southward though glacier-covered North America, presumably chasing mammoths and mastodons as they went.

According to this theory about 14,500 years ago, a 1,500-kilometer (900-mile) north-south corridor opened up between the Cordilleran ice sheet — which covered most of what is now British Colombia in Canada — and the much larger Laurentide ice sheet, which covered most of the rest of Canada. This corridor, the theory does, brought down the blockade that prevented inhabitants of Asia from migrating southward into the Americas. [Source: AFP-JIJI, August 11, 2016 ^^^]

But in recent decades, archaeologists have unearthed much earlier evidence of people across North and South America, pushing back the date for this milestone in human history and casting doubt on how the first Americans got there. According to a study published in Nature in August 2016, the first people to reach the Americas could not have passed through the Ice-Free Corridor because the corridor didn't open until 12,600 years, long after the first Americans had migrated southward and already reached Chile.

Coastal Theory and the Kelp Highway

Jon Erlandson, an archeologist at the University of Oregon, wrote an article New Scientist magazine in 2007, promoting the theory that the first humans in America where people from Asia follow the "Kelp Highway". On the first people to arrive in America he said, “I think they were just moving along the coast and exploring. It was like a kelp highway." He said these people could have arrived sometime after 16,000 years ago when the massive glaciers started retreating from the outer northwest coast of North America.

Backing up this assertion is evidence that the coastlines of northeastern Asia and northwestern America were not as inhospitable as previously thought and could have easily supported migrating, seafaring communities. In the 1990s evidence emerged of a community living on shellfish at a site called Monte Verde on an island off the Chilean coast around 14,850 years ago. It is likely these people arrived by boat. The ice-free corridor mentioned above was blocked until 13,000 years ago.

In 2017 a hearth excavated on Triquet Island off British Columbia was determined to be 14,000 years old, making it one of the oldest human settlements ever discovered in North America and bolstering the Pacific Coastal Migration route hypothosis. [Source: Wikipedia]

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon archaeologist, and Torben Rick, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, propose a pre-Clovis “kelp highway” for coast-hugging seamen skirting the southern edge of the Bering land bridge on their way from northeast Asia to the New World. “People came between 15,000 and 16,000 years ago” by sea, and “could eat the same seaweed and seafood as they moved along the coastline in boats,” Erlandson said. “It seems logical.” [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013]

See Separate Article: MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE FIRST HUMANS in AMERICA factsanddetails.com

Bering Sea and Land Area Only Passable 24,500-22,000 and 16,400- 14,800 Years Ago

During the peak of the last ice age, the overland route between Asia to North America only accessible for a short time and the coastal route was treacherous because of dangerous seas and rough weather. Scientists have determined that humans likely crossed over only during two time windows, when environmental factors were more favorable for making the journey. The first window lasted from 24,500 to 22,000 years ago, and the other lasted from 16,400 to 14,800 years ago, according to a study published February 6, 2023 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. During these periods, winter sea ice cover and sea ice-free summers would have likely given travelers from Asia access to a diverse marine buffet, as well as ways to safely travel along the North Pacific coast, the researchers said. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science February 10, 2023]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: There are two main scenarios explaining how people may have first migrated to the New World. The older idea suggested that people made this journey on land when Beringia — the land bridge that once connected Asia with North America — was relatively ice-free. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that travelers used watercraft along the Pacific coasts of Asia, Beringia and North America before 15,000 years ago, when giant ice sheets would have made an overland journey extraordinarily difficult.

To see how viable the coastal route may have been for migration at different times, scientists analyzed how changes in climate over the past 45,000 years might have influenced sea ice, glacier extent, ocean current strength, and food supplies on land and sea. The researchers developed climate models based on new data on sea ice variations and previously collected sediment samples from the Gulf of Alaska holding details about sea ice, sea surface temperatures, salinity and debris carried on ice. Their models revealed the two time windows — the first 2,500-year-long window and the second 1,600-year-long span — for year-round coastal migration, which would have enabled a favorable coastal route when the inland route was blocked.

During those two windows, summer kelp forests would have helped keep travelers fed. Sea ice during the winter during those periods also may have supported migration; when stuck on the shoreline, sea ice can be relatively flat and stable, so ancient hunters could have walked on it and captured seals, whales and other prey to survive those winters, the researchers noted. "Rather than being an obstacle, we suggest that sea ice may have partly facilitated movement and subsistence in this region," study first author Summer Praetorius, a paleoceanographer at the U.S. Geological Survey, in Menlo Park, California, told Live Science.

Other times during the past 45,000 years were likely less friendly to coastal migration. For instance, a giant pulse of meltwater drained into the Pacific between about 18,500 and 16,000 years ago; this huge pulse came from the edges of the giant ice sheet that once covered most of northeastern North America, and would have more than doubled the average strength of the northward ocean currents along Alaska. This, in turn, would have made boat travel heading south along the Pacific coast more difficult. The melting glaciers at this time also would have led giant icebergs to regularly calve into the ocean, posing a major hazard to coastal migration. "At present we know more about the ice-free corridor — the timing of its opening and the timing of when it became viable for human migration," Michael Waters, an archaeologist at Texas A&M University who did not take part in this research, told Live Science. "This paper is a good step in doing the same for the coastal migration route."

In the future, the researchers would like to "look into how marine ecosystems were changing in response to past climate variations to better understand what resources were available to coastal people at different times," Praetorius said. She also wants to learn more about any brief warming spells a few centuries to millennia long that happened around Beringia, to see if they were linked to specific periods of migration. "It is becoming clear that people entered the Americas by traversing the coast," Waters said. "They took the coastal migration hypothesis to the next level. Well done."

Boating Across the Bering Strait

The notion that ancient people could travel great distances by boat isn’t far-fetched. Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, tolf Live Science: "There's a lot of evidence that suggests that people had the capability to do large ocean crossings." For instance, people used boats to reach Australia by around 50,000 years ago and also crossed long distance at sea to reach some Indonesian islands and perhaps cross from Africa to Europe.. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

Evidence suggests that the first people in America likely boated across the Bering Strait from Asia or skirted the coast and islands south of the strait or the Beringia land bridge. But what was boating in these water like and is there any evidence exists to support their crossings? Amanda Heidt wrote in Live Science: Successive waves of people streamed across the Bering Strait, including members of a group known as the Paleo-Inuit or Paleo-Eskimo who had appeared in the Arctic by 4,500 years ago and belonged to a culture called the Arctic Small Tool tradition (ASTt). It's less clear, however, how they did so. [Source: Amanda Heidt, Live Science, December 30, 2023]

Andrew Tremayne, an archaeologist who previously conducted research in Alaska for the National Park Service, said that ASTt peoples were likely advanced mariners, and artifacts found on islands in the Bering Strait and in Alaska today suggest that ASTt people may have been in the area as early as 5,000 years ago. In the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, in 2013, Tremayne and his team found stone tools from Siberia at an ASTt site dated to about 4,000 years ago."The people that brought that raw material with them either walked across the frozen Bering Strait or boated," Tremayne told Live Science, noting that even now, the 55-mile-wide (89 kilometers) strait sometimes freezes during the winter. "But based on evidence that they had a rather sophisticated maritime culture, I tend to favor the hypothesis that they boated over."

That idea is bolstered by archaeological sites in North America. Once ASTt people arrived in Alaska, some turned northward, wending their boats between the Canadian Arctic's jumble of islands to become the first people to reach Greenland. Along this punishing route, archaeologists have found evidence of marine mammals being used as food and boats that are similar to the umiaks used by today's Yupik and Inuit peoples in Alaska, Canada and Russia. Made of wood or whale bone covered by seal skin and powered by oars or paddles, a large umiak would have held as many as 20 people. "I think of these people as some of the most rugged in the history of humans," Tremayne said. "The ASTt people are the first to really start to make a living in that Arctic maritime environment.' Much later, around 1,000 years ago, ASTt peoples were displaced by the direct ancestors of modern Inuit, Aleut and Yupik peoples who migrated by boat across the Bering Strait from Asia in a later expansion, Tremayne said.

Whether there might have been even earlier water crossings, perhaps by the Clovis people, is a question that may never be answered, Hoffecker said, although the evidence is shifting in that direction. During the last ice age, sea level in the region that includes the land bridge — known as Beringia — was significantly lower, and hundreds of miles of coastline was exposed along Siberia, Alaska and other parts of North America. Today, any coastal sites that early humans might have used during their travels south are buried beneath sea and sediment. But even as the story continues to unfold, Hoffecker said he has become "a strong believer in the Pacific Northwest coast as the main root of migration for the initial movement of people out of Beringia and into the Americas."

Lack of Archaeological Evidence to Back Up Arrival of Humans in America Before 16,000 Years Ago

Fen Montaigne wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Ben A. Potter at the University of Alaska Fairbanks thinks that news stories on the early arrival of humans in America and other findings have been too definitive. “One of the problems with the media coverage is its focus on a single hypothesis — a pre-16,000-year-old migration along the northwest coast — that is not well supported with evidence.” Potter remains doubtful that humans could have survived in most of Beringia during the bitter peak of the ice age, about 25,000 years ago. “Across the board,” he says, “from Europe all the way to the Bering Strait, this far north area is depopulated. There’s nobody there, and that lasts for a long time.”

“But some scientists retort that the reason no sites older than 15,000 to 16,000 years have been discovered in easternmost Siberia or Alaska is that this sprawling, lightly populated region has seen little archaeological activity. The area now defined as Beringia is a vast territory that includes the present-day Bering Strait and stretches nearly 3,000 miles from the Verkhoyansk Mountains in eastern Siberia to the Mackenzie River in western Canada. Many archaeological sites at the heart of ancient Beringia are now 150 feet below the surface of the Bering Strait.

“Ancient sites are often discovered when road builders, railway construction crews or local residents unearth artifacts or human remains — activities that are rare in regions as remote as Chukotka, in far northeastern Siberia. “It means nothing to say that no sites have been found between Yana and Swan Point,” says Pitulko. “Have you looked? Right now there are no [archaeologists] working from the Indigirka River to the Bering Strait, and that’s more than 2,000 kilometers. These sites must be there, and they are there. This is just a question of research and how good a map you have.” Hoffecker agrees: “I think it’s naïve to point to the archaeological record for northern Alaska, or for Chukotka, and say, ‘Oh, we don’t have any sites that date to 18,000 years and therefore conclude that nobody was there.’ We know so little about the archaeology of Beringia before 15,000 years ago because it is very remote and undeveloped, and half of it was underwater during the last ice age.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except last three maps Nature, Jeffrey Bond and phys.org

Text Sources: National Geographic, Wikipedia, Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazineNew York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024