EARLY MODERN HUMANS REACH THE AMERICAS

13,000-year-old footprint in British Columbia

It had long been thought that the first Americans were hunters who crossed a land bridge across the Bering Strait from Siberia to Alaska about 13,500 years ago and followed an “ice-free corridor” southward though glacier-covered North America, presumably chasing mammoths, bisons and mastodons as they went. This theory has largely been dismissed. The latest and most widely accepted theory on the first Americans is that they were fishermen or maybe hunters who traveled in small boats along the coasts of eastern Asia and western America, bridging the two continents by island hoping between Siberia and Alaska. One of main points of contention these days is when these first Americans arrived: the general consensus seems to be around 20,000 years ago. The Bering Land Bridge was exposed and present-day Alaska was connected to the Russian Far East (Siberia) during the last ice age, roughly 38,000 to 11,700 year ago,

In 1997 a team of high-profile archaeologists visited a site in southern Chile called Monte Verde. There Tom Dillehay of Vanderbilt University claimed to have discovered evidence of human occupation dating to more than 14,000 years ago—a thousand years before the Clovis hunters appeared in North America. Like all pre-Clovis claims, this one was controversial, and Dillehay was even accused of planting artifacts and fabricating data. But after reviewing the evidence, the expert team concluded it was solid, and the story of the peopling of the Americas was thrown wide open. /~\

Some DNA evidence provides clues about the migration from North America to South America. Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: People who were genetically similar to the Clovis people journeyed down to South America by 11,000 years ago, another study published this year in the journal Cell found. But these people then mysteriously vanished around 9,000 years ago. It's unclear why, but perhaps another ancient people replaced them, the researchers said. The same study also revealed that ancient people who lived on the Channel Islands, off the coast of California, shared ancestry with ancient people who lived in the southern Peruvian Andes at least 4,200 years ago. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 25, 2018]

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF HUMANS TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

WHEN AND HOW THE FIRST HUMANS CAME TO AMERICA: THEORIES AND EVIDENCE factsanddetails.com ;

SINGLE WAVE VS MULTIPLE PULSE THEORY AND MIGRATION OF EARLY PEOPLE TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST AMERICANS: DNA, ASIA AND ASIANS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN WHAT IS NOW ALASKA AND CANADA factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN WHAT IS NOW THE CONTINENTAL U.S. factsanddetails.com ;

WHITE SANDS 23,000-21,000 YEAR-OLD HUMAN FOOTPRINTS factsanddetails.com ;

CLOVIS PEOPLE: SITES, POINTS, PRE-CLOVIS, MAMMOTHS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHERN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST HUMANS AND SETTLEMENTS IN THE AMAZON factsanddetails.com ;

SOLUTREAN HYPOTHESIS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas” By Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas (Twelve, 2022); Amazon.com;

“First Peoples in a New World: Populating Ice Age America” by David J. Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, (Cambridge University Press, 2021); Amazon.com;

“The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere” by Paulette F. C. Steeves (2023) Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

"The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory" by Thomas D. Dillehay ( Basic Books, 2000 Dated) Amazon.com;

”Strangers in a New Land: What Archaeology Reveals About the First Americans”

by J. M. Adovasio, David Pedler (2016) Amazon.com;

“Paleoindian Mammoth and Mastodon Kill Sites of North America by Jason Pentrail (2021) Amazon.com;

“Clovis The First Americans?: by F. Scott Crawford (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture”

by Dennis J. J. Stanford, Bruce A. Bradley, Michael Collins Amazon.com;

“From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic—Paleo-Indian Adaptations (Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology) by Olga Soffer (1993) Amazon.com;

Were the First Asians to the Americas Following the Kelp Highway

Jon Erlandson, an archeologist at the University of Oregon, wrote an article New Scientist magazine in 2007, promoting the theory that the first humans in America where people from Asia follow the "Kelp Highway". On the first people to arrive in America he said, “I think they were just moving along the coast and exploring. It was like a kelp highway." He said these people could have arrived sometime after 16,000 years ago when the massive glaciers started retreating from the outer northwest coast of North America.

kelp on Victoria Island

Backing up this assertion is evidence that the coastlines of northeastern Asia and northwestern America were not as inhospitable as previously thought and could have easily supported migrating, seafaring communities. In the 1990s evidence emerged of a community living on shellfish at a site called Monte Verde on an island off the Chilean coast around 14,850 years ago. It is likely these people arrived by boat. The ice-free corridor mentioned above was blocked until 13,000 years ago.

In 2017 a hearth excavated on Triquet Island off British Columbia was determined to be 14,000 years old, making it one of the oldest human settlements ever discovered in North America and bolstering the Pacific Coastal Migration route hypothosis. [Source: Wikipedia]

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon archaeologist, and Torben Rick, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, propose a pre-Clovis “kelp highway” for coast-hugging seamen skirting the southern edge of the Bering land bridge on their way from northeast Asia to the New World. “People came between 15,000 and 16,000 years ago” by sea, and “could eat the same seaweed and seafood as they moved along the coastline in boats,” Erlandson said. “It seems logical.” The notion that ancient people could travel great distances by boat isn’t far-fetched; many anthropologists believe that humans voyaged from the Asian mainland to Australia” 65,000 years ago. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013 /||]

“Though Erlandson said he’s convinced that the Clovis people were not the first in the Americas, he acknowledged that definitive proof of a pre-Clovis coastal route may never be found: Whatever beach settlements existed in those days of especially low sea level were long ago submerged or swept away by Pacific tides. /||\

Ice-Free Corridor Route to the Americas

It had long been thought that the first Americans were hunters who crossed a land bridge across the Bering Strait from Siberia to Alaska about 13,500 years ago and followed an “ice-free corridor” southward though glacier-covered North America, presumably chasing mammoths and mastodons as they went.

According to this theory about 14,500 years ago, a 1,500-kilometer (900-mile) north-south corridor opened up between the Cordilleran ice sheet — which covered most of what is now British Colombia in Canada — and the much larger Laurentide ice sheet, which covered most of the rest of Canada. This corridor, the theory does, brought down the blockade that prevented inhabitants of Asia from migrating southward into the Americas. [Source: AFP-JIJI, August 11, 2016 ^^^]

Around 13,500 years ago, according to the theory, the first Ice Age humans moved southward through this “ice-free corridor” to the south. Among the evidence backing up this claim was the fact that the Clovis people — long thought to be the first inhabitants of what is now the United States — didn't show up on the archaeological record until 13,000 years ago. “That coincidence seemed too powerful to ignore," archaeologist David Meltzer of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas told Nature. “People who have been cooling their heels in Alaska for thousands of years see this new land open up and they come blasting down this corridor into the new world." [Source: Ewen Callaway, Nature magazine on August 11, 2016 ||+||]

The theory began to fall apart in the 1990s when string evidence was revealed that people were living in Monte Verde, Chile about 14,000 years ago. The discovery of other possible pre-Clovis sites in North America further undermined the theory that Clovis people were the first Americans. ||+||

Debunking the Ice-Free Corridor Route to the Americas

Ice-free corridor

According to a study published in Nature in August 2016, the first people to reach the Americas could not have passed through the Ice-Free Corridor because the corridor didn't open until 12,600 years, long after the first Americans had migrated southward and already reached Chile. Mikkel Pedersen, a researcher at the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of a study on matter, said: “The earliest point at which the corridor opens for human migration is 12,600 years ago” and while the passage may have been free of ice, “there was absolutely nothing before this date in the surrounding environment — not plants, not animals." In other words, there would have been nothing for these people to eat as they trudged southward through what is now Canada between cliffs of ice."It's 1,500 kilometres. You can't pack a lunch and do it in a day," Meltzer told Nature. [Source: AFP-JIJI, August 11, 2016 ^^^]

AFP reported: Pedersen and colleagues now appear to have closed the door on the inland route for good. The innovative methods they used for reconstructing the late Ice Age ecosystem was crucial. Rather than hunt for DNA traces of specific plants or animals buried in sediment — the standard approach — Pedersen's team used what is called a “shotgun” method, cataloguing every life form in a given sample."Traditionally, we have been looking for specific genes from a single or several species," he explained. “But the shotgun approach really gave us a fantastic insight into all the different trophic” — food-chain — “layers, from bacteria and fungi to higher plants and mammals." ^^^

“The researchers chose to extract sediment cores from what would have been a bottleneck in the inland corridor, an area partly covered today by Charlie Lake in British Columbia. The team did radiocarbon dating, and gathered samples while standing on the frozen lake's surface in winter. Up to 12,600 years ago, the environment was almost entirely bereft of life, they found. But the ecosystem evolved quickly, giving way within a couple of hundred years to a landscape of grass and sagebrush, soon populated by bison, woolly mammoths, jackrabbits and voles. Fast-forward a thousand years, and it had transitioned again, this time into a “parkland ecosystem” dense with trees, moose, elk and bald-headed eagles. ^^^

The findings open “a window onto ancient worlds” and are a cornerstone in a “major re-evaluation” of how humans arrived in America, said Suzanne McGowan of the University of Nottingham, commenting in Nature. They also make the coastal passage scenario much more likely, she added. Other scholars agree. “If there ever was an ice-free corridor during the Last Glacial Maximum," James Dixon of the University of New Mexico wrote in a recent study, “it was not in the interior regions of northern North America, but along the northwest coast." A “biologically viable” passage stretched along that coast from the Bering land bridge to regions south of the glaciers starting about 16,000 years ago, he reported in the journal Quaternary International." ^^^

According to Nature: "Other recent research has hinted that Clovis people and other early humans could not have moved through the ice-free corridor. In June 2016, a team led by Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary palaeobiologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, sequenced ancient DNA from bison that lived to the north and south of the passageway and found that these populations were cut off from each other during the last Ice Age until at least 13,000–13,400 years ago, when they started mixing again. Shapiro, too, now favours the theory of a coastal migration route for humans. [Source: Ewen Callaway, Nature magazine on August 11, 2016]

Plant and Animal DNA Suggests First Americans Took the Coastal Route

In the August 2016 Nature article, archaeologists said that plant and animal DNA buried under two Canadian lakes corroborated the theory that the first Americans travelled along the coasts of northeasternern Asia, southern Alaska and northwestern America rather than through an ice-free corridor that extended from Alaska to Montana. The analysis, led by palaeo-geneticist Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen, provides strong evidence that the passageway became habitable 12,600 years ago, nearly 1,000 years after appearance of the Clovis people —once thought to be the first Americans—and even longer after other, pre-Clovis cultures settled the Americas. [Source: Ewen Callaway, Nature magazine on August 11, 2016 ||+||]

Ewen Callaway wrote in Nature: “To build a picture of the habitat as it crept out of the Ice Age, Willerslev's team analysed DNA in cores taken from beneath two lakes in what was the last stretch of the corridor to melt. The first plant life—thin grasses and sedges—dates back just 12,600 years. The region later became lusher, with sagebrush, buttercups and even roses, followed by willow and poplar trees. This habitat attracted bison first, and later mammoths, elk, voles and the occasional bald eagle. Around 11,500 years ago, the corridor began to resemble the pine and spruce boreal forests of today's landscape. The region's bounty must eventually have tempted hunter-gatherers. But the dates rule out its use as a corridor by Clovis people and earlier Americans to colonize the Americas, says Willerslev. Instead, both probably skirted the Pacific coast, perhaps by boat. ||+||

“Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, agrees: “Now that the ice-free corridor has been shown to be dead in the water—no pun intended—we can start to look at something like a coastal migration route." “Discovering sites along these routes won't be easy, because most are now likely to be underwater. But this summer, Davis and his colleagues began surveying areas of the Pacific Ocean, such as former bays and estuaries that might have served as pit stops for the first Americans. In 2017, the team will start to collect marine sediments to look for signs of habitation, such as stone artefacts or ancient human DNA. Willerslev hopes to be part of the searches, and thinks that recreating these once-coastal habitats through DNA sequencing could prove to be a valuable tool. The fact that early humans advanced to the Americas despite continent-sized glaciers standing in the way has also prompted him to rethink the conventional wisdom that early humans, like other animals, migrated solely in search of food. “Just like people today are trying to reach the top of Mount Everest or the South Pole, I'm sure these hunter-gatherers were also explorers and curious about what would be on the other side of these glacier caps," he says. “When you first reach California, why would you go further? Why not just stay in the Bay Area?”“ ||+||

Japanese-First American Connection?

Studies of skull and facial structures indicates these people were closely related to the Jomon people of Japan (See Below). The skull and facial structures of the Jomon people are in fact more similar to the skull and facial structures of Americans and Europeans than to mainland Asians. In 1996, scientists found a complete skeleton of a 9,300-year-old man in Kennewick, Washington, USA, with "apparently Caucasoid" features similar to those found on Jomon people skulls. This so called "Kennewick Man" is thought to have descended from Jomon people or a common ancestors of the Jomon people.

The oldest form of human DNA recovered in North America — dated to be around 10,300 years old — is common in type to that found in Japan and Tibet. Similar DNA has been found in native Americans all the way down the west coast of North and South America. These people had established themselves in America when a second migration came across the Bering Strait around 5,000 years ago. This second migration is most closely related to native Americans found in the United States today.

Some scientists have theorized the first migrants to the Americas originated from Japan and followed a near continuous belt of kelp forests, rich in fish and other sea creatures, that have existed in coastal waters from Japan to Alaska to southern California and flourished even during the Ice Age. Douglas Preston wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Sometime around 15,000 years ago, the new theory goes, coastal Asian groups began working their way along the shoreline of ancient Beringia—the sea was much lower then—from Japan and Kamchatka Peninsula to Alaska and beyond. This is not as crazy a journey as it sounds. As long as the voyagers were hugging the coast, they would have plenty of fresh water and food. Cold-climate coasts furnish a variety of animals, from seals and birds to fish and shellfish, as well as driftwood, to make fires. The thousands of islands and their inlets would have provided security and shelter. To show that such a sea journey was possible, in 1999 and 2000 an American named Jon Turk paddled a kayak from Japan to Alaska following the route of the presumed Jomon migration. Anthropologists have nicknamed this route the “Kelp Highway." [Source: Douglas Preston, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2014]

There is evidence that people living on Honshu set out across the North Pacific more than 20,000 years ago to Kozushima, an island 50 kilometers away, to collect a type of volcanic glass to make tools. Erland believes these people made the journey in animal skin boats and could have used the same boats to travel northward to Hokkaido, the Kuril islands and Kamchatka Peninsula, all of which, even today, are rich in game and fish. They then continued onto to Alaska and North America. Recently the remains of a seafarer, dated to between 13,000 and 13,200 years old, were found in the Channel Islands off southern California.

Certain stone projectile points, which would have been attached to the ends of spears or dart shafts, found at the 16,000-year-old Cooper's Ferry site in Idaho closely resembled similar types of points found in northern Japan a bit earlier. Oregon State University anthropology professor Loren Davis, who works at the Idaho site said. "We hypothesize that this may signal a cultural connection between early peoples who lived around the northern Pacific Rim, and that traditional technological ideas spread from northeastern Asia into North America at the end of the last glacial period." [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, August 30, 2019]

See Separate Article: FIRST JAPANESE AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE AMERICAS factsanddetails.com

Bison Fossils Suggest Asian Hunters Migrated to Alaska and Then Followed the Coast

Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post: “About 20,000 years ago, Asian hunter-gatherers tracked their prey across a land bridge that linked Siberia with Alaska. A few millennia after that, those transcontinental travelers are thought to have sailed down the North American coast in pursuit of seals and other seafood. Then, some 13,000 years ago, when America's bison began migrating north through a lush land corridor exposed by Canada's melting ice sheets, humans followed them there too. [Source: Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post, June 7, 2016 ++]

“That's the story told by bits of DNA extracted from centuries-old bones uncovered across the continent. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, paleontologists, geneticists and archaeologists describe how humans may have followed bison herds north through a Canadian "ice-free corridor" after their initial colonization of what is now the United States.” ++

“The find addresses the Clovis People and Ice-Free Corridor “theory, suggesting that people arrived here before the route was navigable. The bison bones may well be another nail in the coffin. “This is the first strong empirical data indicating when that corridor was viable,” Michael Waters, an archaeologist at Texas A&M University who was not involved in the study, told Science. “It’s indirect evidence, but it’s still strong evidence.” ++

“At the very end of the Pleistocene, just as the most recent ice age was coming to a close, what is now the United States was separated from Alaska and the "Berengia" land bridge by two massive glaciers that encased all of Canada: the Laurentide ice sheet, which extended from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains, and the Cordilleran, which covered everything west of that. This meant that bison populations that had migrated south during a previous warm period were entirely isolated from their northern counterparts. Distance tends to make creatures drift apart. The southern bison may not have looked much different on the outside, but their distinctiveness was inscribed deep within their cells, in scraps of genetic material known as mitochondrial DNA. ++

“In that difference, evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro saw an opportunity to settle a debate. Scientists haven't been able to definitively date when the corridor opened, instead focusing on tracking evidence of human settlements. But human remains are incredibly hard to find. Before the spread of characteristic fluted Clovis points around 11,000 B.C., we have just a handful of settlement sites, a few stone tools, and a single human coprolite (a fancy term for fossilized poop). Bison fossils, on the other hand, are everywhere. "We thought, why not take advantage of their genetic distinctiveness and ask when the bison individuals of [the southern] genetic type appeared in the north?" said Shapiro, an associate professor at the University of California and an author of the PNAS study. "And then we could use that as a proxy to show that this corridor was habitable at a certain point in time." ++

“So Shapiro and her colleagues began scouring museums and research collections for late Pleistocene bison whose DNA they could test. Genetic analysis showed which specimens were southerners who migrated north, and radiocarbon dating showed when that migration occurred. Ultimately, they concluded that northern and southern bison were mingling in Canada by 13,000 years ago. That's likely too late to make it the initial route into the Americas — stone tools all the way south in Chile indicate that humans were here as many as 5,000 years before then, and just last month researchers found evidence that humans were living in Florida 14,550 years ago. But it could have been "highway two," co-author Jack Ives, an archaeologist at the University of Alberta, told the CBC. Having already settled the lower 48, presumably after traveling down the coast by boat, humans may have migrated back north in the bisons' wake. "It's intriguing from the perspective that as much as bison and game animals were separated, so too would have been early human populations," Ives said. "Once that corridor region opened … this would open the door for human populations to reengage." He and Shapiro cautioned that the bison bone dates are just a proxy for human migration. We can't be sure how humans came to the Americas — and when — until we find their bones. But as far as proxies go, bison are pretty good. "They were definitely on the menu," Ives told the CBC. "... Any place that one would find bison, one would have to strongly suspect, that human beings could be present too."” ++

Difficult Task of Finding Evidence of Early American Migrations

Fen Montaigne wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Today, the coast of the Pacific Northwest bears little resemblance to the world the first Americans would have encountered. The lushly forested shoreline I saw would have been bare rock following the retreat of the ice sheets. And in the last 15,000 to 20,000 years, sea levels have risen some 400 feet. But anthropologist Daryl Fedje and his colleagues have developed elaborate techniques to find ancient shorelines that were not drowned by rising seas. Their success has hinged on solving a geological puzzle dating back to the end of the last ice age. As the world warmed, the vast ice sheets that covered much of North America — to a depth of two miles in some places — began to melt. This thawing, coupled with the melting of glaciers and ice sheets worldwide, sent global sea levels surging upwards. But the ice sheets weighed billions of tons, and as they vanished, an immense weight was lifted from the earth’s crust, allowing it to bounce back like a foam pad. In some places, Fedje says, the coast of British Columbia rebounded more than 600 feet in a few thousand years. The changes were happening so rapidly that they would have been noticeable on an almost year-to-year basis. “At first it’s hard to get your head around this,” says Fedje, a tall, slender man with a neatly trimmed gray beard. “The land looks like it’s been there since time immemorial. But this is a very dynamic landscape.” [Source: Fen Montaigne, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2020]

“That dynamism proved to be a blessing to Fedje and his colleagues: Seas did indeed rise dramatically after the end of the last ice age, but along many stretches of the British Columbia coast, that rise was offset by the earth’s crust springing back in equal measure. Along the Hakai Passage on the central coast of British Columbia, sea-level rise and the rebound of the land almost perfectly canceled each other out, meaning today’s shoreline is within a few yards of the shoreline 14,000 years ago.

“In order to track ancient shorelines, Fedje and his colleagues took hundreds of samples of sediment cores from freshwater lakes, wetlands and intertidal zones. Microscopic plant and animal remains showed them which areas had been under the ocean, on dry land and in between. They commissioned flyovers with laser-based lidar imaging, which essentially strips the trees off the landscape and reveals the features — such as the terraces of old creek beds — that might have been attractive to ancient hunter-gatherers. These techniques enabled the archaeologists to locate, with surprising accuracy, sites such as the one on Quadra Island. Arriving at a cove there, Fedje recalled, they found numerous Stone Age artifacts on the cobble beach. “Like Hansel and Gretel, we followed the artifacts and found them eroding out of the creek bed,” Fedje said. “It’s not rocket science if you have enough different levels of information. We’re able to get that needle into a tiny little haystack.”

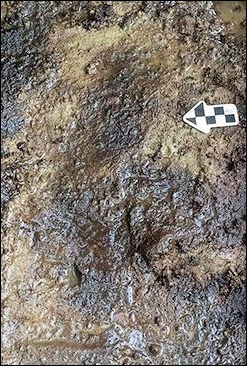

In 2016 and 2017, a Hakai Institute team led by archaeologist Duncan McLaren excavated a site on Triquet Island containing obsidian cutting tools, fishhooks, a wooden implement to start friction fires and charcoal dating from 13,600 to 14,100 years ago. On nearby Calvert Island, they found 29 footprints belonging to two adults and one child, stamped into a layer of clay-rich soil buried under the sand in an intertidal zone. Wood found in the footprints dated back roughly 13,000 years.

“Other scientists are conducting similar searches. Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University, has cruised from San Diego to Oregon using imaging and sediment cores to identify possible settlement sites drowned by rising seas, such as ancient estuaries. Davis’ work inland led to his discovery of a settlement dating back more than 15,000 years at Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho. That find, announced in August 2019, meshes nicely with the theory of an early coastal migration into North America. Located on the Salmon River, which connects to the Pacific via the Snake and Columbia rivers, the Cooper’s Ferry site is hundreds of miles from the coast. The settlement is at least 500 years older than the site that had long been viewed as the oldest confirmed archaeological site in the Americas — Swan Point, Alaska. “Early peoples moving south along the Pacific Coast would have encountered the Columbia River as the first place below the glaciers where they could easily walk and paddle into North America,” Davis said in announcing his findings. “Essentially, the Columbia River corridor was the first offramp of a Pacific Coast migration route.”

“An axiom in archaeology is that the earliest discovered site is almost certainly not the first place of human habitation, just the oldest one archaeologists have found so far. And if the work of a host of evolutionary geneticists is correct, humans may already have been on the North American side of the Bering Land Bridge about 20,000 years ago.

British Columbia footprints

13,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Found in British Columbia

In 2018 scientists announced that they had found 29 footprints left by the water's edge on Calvert Island in British Columbia, Canada They were dated to around 13,000 years ago, when peak glaciation of the last ice age was starting to ebb Imprints so old are incredibly hard to come by so archaeologists were thrilled to discover the shoeless footprints of two adults and a child. They speculated that perhaps ancient people left them as they got out of a boat. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 25, 2018]

Nicola Davis wrote in The Guardian: “While it is not clear quite how many humans were responsible for the tracks, the team said there are at least three different sizes of footprints, including one set that appeared to belong to a child. “We were actively searching for archaeological sites along this lower shoreline when we came across the footprints. It is likely the tracks were left in an area that was just above the high tide line 13,000 years ago,” said Dr Duncan McLaren, first author of the research from the University of Victoria in British Columbia and the Hakai Institute on Calvert Island. [Source: Nicola Davis, The Guardian, March 28, 2018 |=|]

“Writing in the journal Plos One, the team describe how they began excavations on the island in 2014, noting that nearby there were shell-containing man-made rubbish dumps, or middens, which dated to up to 6,100 years ago, as well as chipped stone tools and manmade arrangements of stone boulders on the seashore. “This site has a large, protected beach, which we felt was likely to have attracted people to it for many millennia. As sea level has been relatively stable in the region over the last 14,000 years, we reasoned that this area had potential for very old archaeological remains,” said McLaren.

“The first human footprint was unearthed 60 centimeters below the surface of the current beach, pressed into a layer of brown clay and filled with black sand and gravel. Fortunately, small pieces of wood were discovered in the heel of the print, and were radiocarbon-dated to just over 13,000 years ago. |The team returned during 2015 and 2016 to carry out further excavations, uncovering another 28 footprints. In some cases it was possible to see the impressions of individual toes and arches of the feet. Measurements of 18 of the tracks revealed they were made by at least three different individuals. “We had to excavate very carefully and slowly, which was difficult as we had to race the tide,” said McLaren. |=|

“McLaren said the finds helped to unpick a longstanding conundrum. In the last ice age, Siberia and Alaska were connected by a large land bridge in an area known as Beringia, while Canada was covered in ice sheets.“The basic question that many archaeologists ask is: ‘How did people get from Beringia to the area south of Canada during the last ice age?’” said McLaren. “The new research adds weight to the idea that humans moved along glacier-free areas of land along the coast, between the ice and the sea – areas known to have provided a refuge for various plants and animals. “It suggests that people were using watercraft, and thriving and exploring coastal areas very early on,” McLaren said.” |=|

Feces Offer Clues of Coastal Migration

Until recently, the record holder for oldest human coprolites (petrified shit) unearthed by archaeologists came from Oregon's Paisley Caves. Far older fecal samples from dinosaurs and ancient sharks have also been uncovered by researchers. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Perhaps ironically, the best evidence for a coastal migration might be found inland, as people traveling along the coast would likely have explored rivers and inlets along the way. There is already suggestive evidence of this in central Oregon, where projectiles resembling points found in Japan and on the Korean Peninsula and Russia’s Sakhalin Island have been discovered in a series of caves, along with what is surely the most indelicate evidence of pre-Clovis occupation in North America: fossilized human feces. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, January 2015 /~]

“In 2008 Dennis Jenkins of the University of Oregon reported that he’d found human coprolites, the precise term for ancient excrement, dating to 14,000 to 15,000 years old in a series of shallow caves overlooking an ancient lake bed near the town of Paisley. DNA tests have identified the Paisley Caves coprolites as human, and Jenkins speculates that the people who left them might have made their way inland from the Pacific by way of the Columbia or Klamath Rivers. /~\

“What’s more, Jenkins points to a clue in the coprolites: seeds of desert parsley, a tiny plant with an edible root hidden a foot underground. “You have to know that root is down there, and you have to have a digging stick to get it,” Jenkins says. “That implies to me that these people didn’t just arrive here.” In other words, whoever lived here wasn’t just passing through; they knew this land and its resources intimately.” /~\

Paisley Caves in Oregon

Channel Islands, California and Evidence of Coastal Migration

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “The Channel Islands off the southern California coast are rugged and” harbor “thousands of archaeological sites, most of them still undisturbed.

In 1959, while exploring Santa Rosa Island, museum curator Phil Orr discovered a few bones of a human he named Arlington Springs man. At the time, the bones were judged to be 10,000 years old, but 40 years later researchers using improved dating techniques fixed the age at 13,000 years—among the oldest human remains ever discovered in the Americas. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, January 2015 /~]

“Thirteen thousand years ago the northern Channel Islands—then fused into a single island—were separated from the mainland by five miles of open water. Clearly Arlington Springs man and his fellow islanders had boats capable of offshore travel. Jon Erlandson of the University of Oregon has been excavating sites on these islands for three decades. He hasn’t found anything as old as Arlington Springs man, but he has found strong evidence that people who lived here slightly later, some 12,000 years ago, had a well-developed maritime culture, with points and blades that resemble older tools found on the Japanese islands and elsewhere on the Asian Pacific coast. /~\

“Erlandson says that the Channel Island inhabitants might have descended from people who traveled what he calls a kelp highway—a relatively continuous kelp-bed ecosystem flush with fish and marine mammals—from Asia to the Americas, perhaps with a long stopover in Beringia. “We know there were maritime peoples using boats in Japan 25,000 to 30,000 years ago. So I think you can make a logical argument that they may have continued northward, following the Pacific Rim to the Americas.”

Beaches along the Pacific coast still teem with elephant seals and sea lions, and it’s easy to imagine hunters in small boats moving swiftly down the coastline, feasting on the abundant meat. But imagination is no substitute for hard evidence, and as yet there is none. Sea levels are 300 to 400 feet higher than at the end of the last glacial maximum, which means that ancient coastal sites could lie under hundreds of feet of water and miles from the current shoreline.” /~\

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Moreover, the Channel Islands projectiles have nothing in common with Clovis points, as Erlandson pointed out. They appear to be related to a different toolmaking approach called the western stemmed tradition; featuring stems of different shapes that attach the projectile points to spears or darts, they were prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and the Great Basin. And they do not have the fluting characteristic of Clovis. Those observa―tions strengthen the view that other tool-making human cultures were present in the Americas at the same time as the Clovis people, and in all likelihood beforehand as well. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013 /||]

Did a Drive to Explore Motivate Early Americans to Push

Fen Montaigne wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“Once in the New World, the first Americans, probably numbering in the hundreds or low thousands, traveled south of the ice sheets and split into two groups — a northern and southern branch. The northern branch populated what are now Alaska and Canada, while members of the southern branch “exploded,” in Willerslev’s words, down through North America, Central America and South America with remarkable speed. [Source: Fen Montaigne, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2020]

Such a movement could account for the growing number of archaeological sites dating from 14,000 to 15,000 years ago in Oregon, Wisconsin, Texas and Florida. Far to the south, at Monte Verde in southern Chile, conclusive evidence of human settlement dates back at least 14,500 years. “I think it has become more and more clear, based on the genetic evidence, that people were capable of much more in terms of spreading out than we thought,” says Willerslev. “Humans are very early on capable of making incredible journeys, of [doing] things that we, even with modern equipment, would find very difficult to achieve.”

“In Willerslev’s view, what primarily drove these ancient people was not the exhaustion of local resources — the virgin continents were too rich in food and the numbers of people too small — but an innate human yearning to explore. “I mean, in a few hundred years they are taking off across the entire continent and spreading into different habitats,” he says. “It’s obviously driven by something other than just resources. And I think the most obvious thing is curiosity.”

DNA Studies on the Relationship Between North and South Americans

Some studies have suggested that the first Americans diverged genetically from their Siberian and East Asian ancestors about 25,000 years ago. These people traveled across the Bering Strait Land Bridge and eventually split into distinct North and South American populations. By about 13,000 years ago, people of the Clovis culture, known for its use of distinctive, pointy stone tools, came to occupy much of North America. But by this time, people were already living as far south as Monte Verde, Chile. They had been there since a least 14,500 years ago, according to archaeological findings there. Still it is not totally clear how the Clovis culture were linked to populations in South America. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, November 9, 2018]

According to an ancient DNA analysis published online November 8, 2018 in the journal Cell prehistoric people from different populations made their way across the Americas thousands of years ago. People genetically linked to the Clovis culture, one of the earliest and best-known cultures in North America, migrated into South America as far back as 11,000 years ago but then mysteriously disappeared around 9,000 years ago. The 2018 study says that another ancient group of people replaced them, but it is certain how or why this occurred, and the population turnover happened across the entire continent of South America.

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: To unravel the genetic mysteries of the these ancient Americans, the researchers reached out to indigenous peoples and government agencies all over Central and South America, asking for permission to study the remains of ancient peoples that have been discovered over the years. In all, the international team of scientists was given permission to do genomewide analyses on 49 ancient people whose remains were unearthed in the following Central and South American countries: Belize, Brazil, Peru, Chile and Argentina. The oldest of these people lived about 11,000 years ago, marking this as a study that takes a big step forward from previous research, which only included genetic data from people less than 1,000 years old, the researchers said.

Their findings showed that DNA associated with the North American Clovis culture was found in people from Chile, Brazil and Belize, but only between about 11,000 to 9,000 years ago. "A key discovery was that a Clovis culture-associated individual from North America dating to around 12,800 years ago shares distinctive ancestry with the oldest Chilean, Brazilian and Belizean individuals," study co-lead author Cosimo Posth, postdoctoral researcher of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, said in a statement. "This supports the hypothesis that the expansion of people who spread the Clovis culture in North America also reached Central and South America." [In Photos: New Clovis Site in Sonora]

Curiously, around 9,000 years ago, the Clovis lineage disappears, the researchers found. Even today, there is no Clovis-associated DNA found in modern South Americans, the researchers said. This suggests that a continentwide population replacement happened at that time, said study co-senior researcher David Reich, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Following this mysterious disappearance, there is a surprising amount of genetic continuity between people who lived 9,000 years ago and those living today in multiple South American regions, the researchers said.

Although these findings shed light on early Americans, it's far from complete. The researchers acknowledge that they don't have human remains that are older than about 11,000 years old, "and thus we could not directly probe the initial movements of people into Central and South America," they wrote in the study. Moreover, although the study looked at 49 people who lived between about 11,000 and 3,000 years ago, the research would be more comprehensive if more ancient individuals from different regions were included, the researchers said.

"We lacked ancient data from Amazonia, northern South America and the Caribbean, and thus cannot determine how individuals in these regions relate to the ones we analyzed," Reich said in the statement. "Filling in these gaps should be a priority for future work."

California-Peruvian Connection

The 2018 Cell study also revealed an unexpected connection between ancient people living in California's Channel Islands and the southern Peruvian Andes at least 4,200 years ago. It appears that these two geographically distant groups have a shared ancestry, the researchers found. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, November 9, 2018]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: It's unlikely that people living in the Channel Islands actually traveled south to Peru, the researchers said. Rather, it's possible that these groups' ancestors sallied forth thousands of years earlier, with some ending up in the Channel Islands and others in South America. But those genes didn't become common in Peru until much later, around 4,200 years ago, when the population may have exploded, the researchers said.

"It could be that this ancestry arrived in South America thousands of years before and we simply don't have earlier individuals showing it," study co-lead researcher Nathan Nakatsuka, a research assistant in the Reich lab at Harvard Medical School, said in the statement. "There is archaeological evidence that the population in the Central Andes area greatly expanded after around 5,000 years ago. Spreads of particular subgroups during these events may be why we detect this ancestry afterward."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except British Columbia footprints, Scientific American

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024