WHITE SANDS FOOTPRINTS

The oldest evidence of modern humans in the continental United States is a set of human footprints found at Lake Otero in White Sands National Park in southern New Mexico that may date to 23,000 years ago. These footprints date to before the peak of the ice age about 20,000 years ago. Some archaeologists question the dates, casting doubts on dating methods and view evidence for human presence circumstantial and would prefer to see directly dated skeletons or genetics to confirm these dates. [Source: Wikipedia, Live Science]

White Sands has the world’s largest collection of fossilized Ice Age footprints, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. By comparison, Laetoli, the Tanzanian site with the world’s oldest-known hominin footprints, extends about 88 feet and contains fewer than 100 tracks. No one knows who the early human trackmakers were or whether they were genetically related to Native groups in the region today,

The White Sands footprints have been described as the earliest "unequivocal evidence" of people in the Americas. The footprints are still visible thanks to a megadrought that lowered the water levels and dried-up lake called Lake Otero, exposing swampy ground that preserved tracks left by humans and animals. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

Up until the early 2010s it was widely thought that humans didn’t arrive in North America closer until 13,500 – 16,000 years ago. The White Sands footprints and other finds with later dates have largely debunked that. The 23,000 year old date for the foot prints was arrived at by dating sediments above and below the footprints. In these sediments were ancient grass seeds (Ruppia cirrhosa) which were analyzed using radiocarbon dating, which yielded calibrated dates of 22,860 years ago (∓320 years) and 21,130 years ago (∓250 years). [Source: National Park Service]

These fossilized footprints, among other natural and cultural features found in the dunefield, led to the re-designation of White Sands National Monument into White Sands National Park. As scientists debate over dating continues, there are most likely many more discoveries to be made at White Sands. According to the New York Times thousands of tracks pepper the salty landscape. “There’ll be people working there for lifetimes,” one scientist said. “There’s that much to do.” While other archeological sites in the Americas have produced similar date ranges — including pendants carved from giant ground sloth remains in Brazil — scientists still have doubts as to whether such materials really indicate human presence. “White Sands is unique because there’s no question these footprints were left by people, it’s not ambiguous,” Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas, told Associated Press.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas” By Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas (Twelve, 2022); Amazon.com;

“First Peoples in a New World: Populating Ice Age America” by David J. Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, (Cambridge University Press, 2021); Amazon.com;

“The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere” by Paulette F. C. Steeves (2023) Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

"The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory" by Thomas D. Dillehay ( Basic Books, 2000 Dated) Amazon.com;

”Strangers in a New Land: What Archaeology Reveals About the First Americans”

by J. M. Adovasio, David Pedler (2016) Amazon.com;

“Paleoindian Mammoth and Mastodon Kill Sites of North America by Jason Pentrail (2021) Amazon.com;

“Clovis The First Americans?: by F. Scott Crawford (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture”

by Dennis J. J. Stanford, Bruce A. Bradley, Michael Collins Amazon.com;

“From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic—Paleo-Indian Adaptations (Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology) by Olga Soffer (1993) Amazon.com;

Landscape of the White Sands Area Now and in the Past

White Sands National Park embraces the world's largest gypsum dunefield and is situated in New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin. The sun shines bright here nearly 300 days a year. The dunes abut the dried-up bed of prehistoric Lake Otero, which once covered 4,144 square kilometers (1,600 square miles) In the summer, park temperatures can reach to 43.3ºC (110º F) , and the intense sunlight and glare reflecting off the white sand can strain the eyes. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Today, the White Sands landscape, with its crests of glimmering dunes, forms a panorama of snow-white land in a summer broil. There are no trees, save for a few solitary invasive species that suck whatever moisture they can from the land. Miles of undulating sands give way to the crisp, flat surface of the dried-up ancient Lake Otero, which is dotted with iodine bush, a desert shrub adapted to sandy, salty, alkaline soils. To the east and west of the park, a heat haze distorts the peaks of towering mountains.

The oldest prints date to around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500 to 19,000 years ago), the coldest part of the last ice age, when glaciers reached their greatest extent and thickness and sea levels were low. Back then Lake Otero was a large body of water within the Tularosa basin. The climate was much wetter than it is today and the vegetation was abundant. Vast grasslands stretched for miles bring to mind the prairies of the Midwest rather than the deserts of New Mexico. Large Ice Age animals gathered here. They included herbivores such as ancient camels, Columbian mammoths and Harlan’s ground sloth and predators such dire wolves and American lions. Footprints from these animals remained long after Lake Otero dried up and they eventually became fossilized. [Source: National Park Service]

According to Coates: At the time when many of the tracks were made, researchers think Lake Otero had already begun to evaporate and a series of small seasonal bodies of water covered the area. As the water evaporated over time, it formed a playa—the flat bottom of a desert basin that occasionally fills with water. About 15 years ago, a rare flood filled that playa with so much water that waves beat against the ancient shoreline and eroded its sediments, exposing trackways never before seen. Not long after that, Bustos began finding prints left by mammoths on the shoreline as well as elongated prints he thought might be human. As time passed, he and other researchers found more and more trackways from what appeared to be an array of species, including humans, mammoths, bison, camels, dire wolves, and saber-toothed cats. Some of the marks show evidence of people and animals slipping and sliding across what was then a muddy surface. “Many of the footprints actually have layers of algae, which would have required moisture to grow,” says Cornell University archaeologist and team member Tommy Urban.

Who Made the White Sands Footprints

For 80 years, only a small collection of fossilized footprints were known to exist at White Sands. However, in 2006, a group of scientists noticed dark spots dotting the expanse of the lakebed that appeared to be footprints. Their curiosities lead them to dig up these dark spots in 2009. This led to the discovery of both Harlan’s ground sloth and human footprints. During the 2010s, footprints of a dire wolf were discovered. These footprints were located next to ancient seeds. Scientists dated these seeds to more than 18,000 years ago.[Source: National Park Service]

According to New York Times: The footprints are ancient vignettes cast in gypsum-rich sand. They tell stories of hunters stalking a giant sloth; a traveler slipping in mud with a child on one hip; children jumping in puddles, splashing in play; and more. [Source: Maya Wei-Haas, The New York Times, October 8, 2023]

In 2018, researchers discovered what they believe to be footprints of a female. They tell a story that may seem familiar today; her footprints show her walking for almost a mile, with a toddler’s footprints occasionally showing up beside hers. Evidence suggests that she carried the child, shifting them from side to side and occasionally setting the child down as they walked. The footprints broadened and slipped in the mud as a result of the additional weight she was carrying.

Based on stature and walking speed, it appears that most of the footprints in this study come from teenagers and children. As reported in the journal Science, “One hypothesis for this is the division of labor, in which adults are involved in skilled tasks whereas 'fetching and carrying' are delegated to teenagers. Children accompany the teenagers, and collectively they leave a higher number footprints that are preferentially recorded in the fossil record. This pattern is common to all excavated surfaces.” (Bennett, 2021)

Human and Large Animal Interactions Revealed by the White Sands Footprints

Footprints across White Sands have been found coexisting and interacting with extinct ice age animals. One set of footprints shows what appears to be humans stalking a giant sloth. This is demonstrated by human footprints being found inside the footprints of the sloth as they were tracked. Unfortunately for our hunter, there is no evidence that this was a fruitful hunt. [Source: National Park Service]

Although the reason for the disappearance of the great animals of the ice age is still debated, most theories do agree that climate change had a major influence. Environments once rich in lush green life began to disappear as those regions began experience less rainfall and higher temperatures. The fossilized footprints of White Sands are probably the most important resources in the Americas to understand the interaction of humans and extinct animals from the ice age.

Christina Larson of Associated Press wrote: Ancient footprints of any kind — left by humans or megafauna like big cats and dire wolves — can provide archaeologists with a snapshot of a moment in time, recording how people or animals walked or limped along and whether they crossed paths. Animal footprints have also been found at White Sands.

Between the outbound and return legs of the trip by two humans, a giant ground sloth and a mammoth crossed their pathway. The mammoth crossed a human’s path after the human passed on his or her northbound journey. Hours later, the human stepped in the mammoth footprints on the southbound trip back. Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The mammoth walked in a straight line, leaving no evidence of having noticed, or cared, that humans were in the vicinity. But the sloth behaved differently. Variations in the animal’s footprints appear to show that it stood on its hind legs and spun around, possibly catching a whiff of danger before dropping to all fours and rambling off in a different direction. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Dating the White Sands Footprints

A paper published in the journal Science in 2021 said the White Sands footprints were made as early as 21,000 to 23,000 years ago, making them some of the oldest evidence of people in the Americas. Many were skeptical though. Questions revolved around whether seeds of aquatic plants used for the original dating may have absorbed ancient carbon from the lake — which could, in theory, throw off radiocarbon dating by thousands of years. More test were done with two additional lines of evidence for the older date range relying on two entirely different materials found at the site, ancient conifer pollen and quartz grains. A study published in October 2023 in Science revealed the results. “We knew it was going to be controversial all along,” said Kathleen Springer, a geologist of the United States Geological Survey and a co-author of the 2023 paper. So when the team published its earlier study, plans were already in the works for more research. [Source: Maya Wei-Haas, The New York Times, October 8, 2023; Christina Larson, Associated Press, October 6, 2023]

“This is a subject that’s always been controversial because it’s so significant — it’s about how we understand the last chapter of the peopling of the world,” Thomas Urban, an archaeological scientist at Cornell University, told Associated Press. He was involved in the 2021 study but not the 2023 one. Thomas Stafford, an independent archaeological geologist in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who was not involved in the study, said he “was a bit skeptical before” but now is convinced. “If three totally different methods converge around a single age range, that’s really significant,” he said.

Maya Wei-Haas wrote in The New York Times: The dates in the 2021 study relied on analysis of seeds from ruppia, an aquatic grass. Some scientists raised concerns that a phenomenon called the reservoir effect could result in murky radiocarbon results for the aquatic plants. So, for the latest study, the team turned to carbon isotope analysis of ancient pollen from terrestrial plants, extracting nearly 75,000 pollen grains from many pounds of sand from layers interspersed with the trackways at the New Mexico site. [Source: Maya Wei-Haas, The New York Times, October 8, 2023]

“We’ve got seed ages, we’ve got pollen ages, we’ve got luminescence ages — they all converge,” said Jeff Pigati, a USGS geologist and co-author of the study. “They all agree, and it’s really tough to argue against that.” Many outside scientists not associated with the work agree. “It’s kind of a master class in how you execute scientific responses to criticism,” said Edward Jolie, an archaeologist at the University of Arizona. Jolie, who is affiliated with the Oglala Lakota and the Hodulgee Muscogee, also notes the excitement these finds have for Native people. “It’s another one of those ‘We told you so,’” he said. “A lot of natives have said we’ve always been here.”

Still, some scientists are not convinced. “We just have to acknowledge that none of these approaches are perfect,” said Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University. Among his concerns is that only one sediment layer was dated using optically stimulated luminescence. The method can lack precision as it requires making challenging estimates about factors such as the sample’s moistness since deposition. More luminescence dates from layers of sediment throughout the track layers are vital for confirmation, he said. But the unique conditions that affect the accuracy for each method are part of the strength of the latest result, said Thomas Stafford, a geochronologist with Stafford Research, who was not involved in the work. “If three entirely different dating methods produce similar ages, this is strong evidence that the 21,000-year dates are correct,” he said.

How the White Sands Footprints Were Dated

The 2023 study isolated about 75,000 grains of pure pollen from the same sedimentary layer that contained the footprints. “Dating pollen is arduous and nail-biting,” Springer told Associated Press. Scientists believe radiocarbon dating of terrestrial plants is more accurate than dating aquatic plants, but there needs to be a large enough sample size to analyze, she said. The researchers also studied accumulated damage in the crystal lattices of ancient quartz grains to produce an age estimate. [Source: Christina Larson, Associated Press, October 6, 2023]

According the New York Times: The nearly yearlong process revealed pollen from a verdant landscape when cooler temperatures prevailed, as would be expected during the Last Glacial Maximum. Fir, spruce, pine and sagebrush abounded. The largest of these pollen grains, mostly pine, was subjected to carbon analysis at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. The team also worked on determining the date of a layer of the White Sands sediments using a method known as optically stimulated luminescence, which, in essence, reveals how long quartz sand has sat beneath the surface.

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Scientists had found the seeds smooshed into the footprints, providing organic remnants that could be dated by examining the radioactive decay of their carbon-14. But "Ruppia is a notorious misreporter of its age," Loren Davis, a professor of anthropology at Oregon State University who co-authored the rebuttal of the study, told Live Science. Unlike other once-living organisms that inhale carbon-14 from the atmosphere, "Ruppia prefers to get its carbon from lake water, it doesn't get it from the atmosphere. And in doing so, if there is old carbon being put into the groundwater, then you'll get old ages on plants that are not that old," Davis said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science October 6, 2023]

In the rebuttal, Davis and his colleagues suggested the White Sands group use optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, a technique that estimates how much time has passed since quartz or feldspar grains were last exposed to intense heat or sunlight. So, for the 2023 paper the researchers did just that. The team examined quartz grains under the footprints with OSL dating. They found that the layers with the footprints had a minimum age of about 21,500 years old. The team also isolated and then radiocarbon dated three samples of earth that each contained 75,000 conifer pollen grains from the same footprint layers as the Ruppia seeds. Confer plants get their carbon-14 from the atmosphere, meaning they don't have the same pitfalls as Ruppia. The ages of around 23,000 years ago matched those of both the seeds and the quartz grains. "If the seed ages and the pollen ages and the luminescence ages all agree, then it's case closed," Pigati said. "We can stop arguing about the ages."

According to a map showing where the White Sands team took the OSL samples, "it is clear that the three OSL ages come from sediments that are stratigraphically beneath the trackway horizons," Davis told Live Science. So it's possible that the quartz grains were deposited first and that the footprints were deposited on top of them at a later date, possibly between 19,800 and 16,200 years ago, as one OSL sample demonstrates, he said. "This is why it is critical that the authors continue their efforts to get OSL ages from the sediments that actually buried the footprints," Davis said. He added that it's possible that erosion of older sediments at the lake basin could have caused fossil pollen to be redeposited elsewhere at a later time, meaning that the pollen could be older than the footprints.

Springer and Pigati said the OSL samples were taken from the same layer as the footprints, while Davis stood by his interpretation of their data. But others were impressed by the findings. "I think it's a really great contribution and a very convincing and detailed case," Thomas Higham, an archaeological scientist and radiocarbon dating specialist at the University of Vienna who was not involved with the study. He disagreed with Davis' take that more OSL data is needed. "Getting those samples is not an easy feat," Higham said, adding that the team took the lower-dated layer into account and used a model to bracket the ages of the footprints above them. The initial 2021 finding was "a groundbreaking result," Higham told Live Science. "I think that duplicating and reproducing those results is a hallmark of the scientific method."

What the White Sands Footprints Say About the Humans Who Made Them

Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology Magazine: he team found a human pathway that goes out and back, extending nearly a mile. Based on footprint size, scientists believe it was made by a woman or adolescent male, accompanied by a toddler on the outward journey. Analysis of the tracks shows that the child was occasionally carried during the journey. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

The researchers concluded that the chaperone on the excursion at times carried the toddler, shifting the child from hip to hip. This subtle change in behavior is reflected in the alternating shape of the footprints, which broaden with added weight to form a banana shape created by the outward rotation of the older person’s foot. They can also tell this was a speedy trip, completed at a pace of 5.5 feet per second through slick mud—far faster than that of a person walking at a comfortable pace of four feet per second over dry, flat land. They determined this by creating a mosaic of aerial images of a large section of the trackway that encompassed hundreds of prints. This allowed them to calculate the people’s average stride lengths. The researchers don’t know the purpose of the trek, or why it was made so quickly, except to note that the dangerous beasts of the Ice Age world would have given people plenty of reasons to hurry, especially with a child in tow.

The track is 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) long — the longest late Pleistocene double human trackway found anywhere in the world. Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: Excavations revealed fossilized footprints just below the loose white gypsum sand. These tracks were originally made on wet ground. As the water evaporated, it left behind the minerals dolomite and calcite, which created rocky molds of the footprints. The tracks run north/northwest in a straight line in one direction before disappearing into the dunes. Next to them are the remains of the return south/southwest return journey, which appears to have been made by the same person, judging by the size of the footprints and the stride length. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, October 16, 2020]

Northbound, the adult tracks are a little asymmetrical, evocative of a woman holding a child on one hip. At times, the child's footprints appear, perhaps during rest breaks when the adult put the squirmy toddler down. There are no child footprints on the return southbound journey, suggesting that perhaps the trip was taken in order to drop off the child somewhere. "Motivation is something we can't really speak to in the fossil record, but it's something we want to know," said Sally Reynolds, a paleontologist at Bournemouth University in the U.K. and the senior author of a paper on the tracks published in the December 2020 issue of the journal Quaternary Science Reviews. Reynolds speculated that perhaps the child was ill and needed to be taken to another camp where someone could help him or her. Whatever the reason for the journey, it seemed very goal-oriented: The footprints didn't deviate and the walker didn't dawdle. The stride length suggests that the person was walking about 5.5 feet (1.7 meters) per second, a brisk pace. The region was arid, but the journey was near an ancient, now-vanished lake, and the ground was muddy and slippery. "We do know the journey was faster than normal speed and over terrain that would have been more tiring than normal," Reynolds said.

The journey would have taken the pair through a landscape prowled by predators such as dire wolves and saber-toothed cats. Fortunately, the woman and child seem not to have been menaced; instead, they may have scared some of the animals that encountered their trackway. After the pair passed north, a set of animal tracks shows that a giant sloth approached their tracks, reared up — perhaps sniffing the air? — and then shuffled in a circle before veering away. The human then stepped on these sloth tracks when returning southbound. Previous research in the area suggests that humans hunted giant sloths, perhaps explaining why the sloth footprints reveal signs of nervousness on the part of the animal. Reynolds said. Based on the known extinction dates for mammoths and giant sloths, the tracks must be at least 10,000 years old and possibly as old as 13,000 years, she said. She and her colleagues plan to publish data next year on the age of seeds found beneath other tracks in the park.

White Sands Footprints Appear to Show Early Humans Stalking a Giant Sloth

A study was published online April 25, 2018 in the journal Science Advances described what appeared to be humans stalking a two-meter tall ground sloth about 11,000 years ago. Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: No matter which way the giant creature went, ancient humans followed it, stepping in its elongated, kidney-shaped paw prints as they tracked the furry beast...Finally, it seems that the giant ground sloth couldn't take it anymore. It reared up on its hind legs and swung its sharp, sickle-shaped claws around, looking at the unwanted human interlopers, according to an analysis of the fossilized foot, paw and claw marks left at the site. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 26, 2018]

What happened next remains a mystery. It's possible the humans attempted to kill the sloth and may have succeeded, said study co-researcher Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom. But, given that the vast majority of hunts led by modern-day hunter-gatherers aren't successful, and that "sloths are so densely muscled," it would have been hard to overpower the animal with a stone weapon, so an outright kill is unlikely, the researchers wrote in the study.

Researchers found the prints left by this giant ground sloth and humans at White Sands National Park in April 2017. The sloth prints were between nearly 30 and 56 centimeters (12 and 22 inches) long. Some of the human footprints were found inside the sloth tracks, indicating that ancient people had followed the prints while they were still fresh in the sandy mud. Track marks from other giant, now-extinct animals, including mammoths, wolves, big cats, camels and cattle have also been found on the fossil-rich site.However, there were fewer than a dozen sloth track marks with human footprints inside, Bennett said. These sloth tracks were likely left by either Nothrotheriops or Paramylodon and were likely made by several animals of different ages, the researchers said.

The prints reveal that ancient humans and giant ground sloths did, in fact, interact at the end of the last ice age. This evidence is key to figuring out whether humans stalked and hunted the furry giants, which went extinct around this time, as did other large mammals, including the mammoth and North American horse. There's an ongoing debate about whether human hunters or climate change ultimately led to the extinction of these large creatures, Bennett said. According to a 2016 study in the journal Science, a perfect storm of humans and a warming climate doomed the ice age giants.

Researchers have presented some ideas about what the sloth and human tracks show. One is that human hunters were following and harassing the giant ground sloths, distracting them so they could be more easily hunted, the researchers said. Another idea is that humans' actions were playful and curious rather than ominous. "But human interactions with sloths are probably better interpreted in the context of stalking and/or hunting," the researchers wrote in the study. "Sloths would have been formidable prey. Their strong arms and sharp claws gave them a lethal reach and clear advantage in close-quarter encounters."

According to Natural History magazine: Every indication suggests one person followed quickly behind the animal. The person matched the sloth’s stride—which was much longer than a comfortable human stride—for more than 10 paces until the sloth, it seems, rose on its hind limbs and flailed in defense. Meanwhile, a second person approached the animal on tiptoe from the side. The tracks are the best direct evidence of late Pleistocene interactions between humans and megafauna found anywhere in the world, and it seems likely they were made by two hunters confronting their prey—though whether they or the sloth prevailed isn’t clear. The notion of hunting in the region fits with more recent Native oral histories, too. “Our tribal partners have stories about the ‘white sands’ and coming down for hunting parties,” says White Sands archaeologist Clare Connelly. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

The study is a "solid" one — "they have done a very thorough job of documenting and analyzing the trackways," said William Harcourt-Smith, a paleoanthropologist at Lehman College and the American Museum of Natural History, told live Science. But it's good to be cautious when imagining the ancient scene, Harcourt-Smith said. It's possible that the sloths made the tracks and humans followed an hour or so later — meaning that the humans weren't hot on the sloths' tail. "How many times have children, or even adults, followed in the footsteps of others in the snow or sand, simply for the fun of it?" Harcourt-Smith told Live Science. However, it's definitely possible that the "flailing" marks that the sloth made in the ground with its enormous claws were prompted by the presence of humans, Harcourt-Smith said. But without any surviving weapons or butchered animal bones, it's anyone's guess what happened next, he said.

White Sands Footprints Appear to Show Early Human Kids Playing in 'Giant Sloth Puddles'

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: More than 11,000 years ago, young children trekking with their families through what is now White Sands National Park and discovered the stuff of childhood dreams: muddy puddles made from the footprints of a giant ground sloth. Few things are more enticing to a youngster than a muddy puddle. The children — likely four in all — raced and splashed through the soppy sloth trackway, leaving their own footprints stamped in the playa — a dried up lake bed. "All kids like to play with muddy puddles, which is essentially what it is," Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the U.K. who is studying the trackway, told Live Science. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 25, 2022]

Bennett found that there were more than 30 footprints crisscrossing the sloth trackway, likely from children between the ages of 5 and 8 years old, Bennett said. The tracks that Bennett analyzed aren't an accurate representation of the children's feet, as the squishy mud distorted each print, but Bennett was able to compare the preserved, smeary footprints with modern growth data to deduce the children's ages.

The now-extinct giant ground sloth, possibly Nothrotheriops, left its trackway after walking through the area on all fours. Each sloth print is actually a double print, Bennet said. "As it puts its forepaws down, the rear paw comes and steps on it," he explained. This combination of front and back paw gives the prints a kidney shape.

Each of the giant ground sloth footprints measures nearly 16 inches (40 centimeters) long, and the beast would have been anywhere from the size of a cow to as big as a bear, Bennet said. The footprints are shallow, about 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) deep, but it seems that was deep enough for them to fill with water and intrigue the children. "We see children's tracks very frequently at White Sands," most likely because, just like today's children, these youngsters raced around, leaving hundreds of footprints a day, Bennett said.

The children and adults in the group were "almost certainly" foragers who stuck together while searching for food, he added. "In the past, you would have just taken your kid to work. And if work was walking across the former lake bed in order to track an animal, you would have taken your child with you."

It's challenging to date footprints without a detailed stratigraphy — or studying the rock layers — of the site and without finding any organic matter, which can be radiocarbon dated. But based on the discovery of the 23,000-year-old prints and the fact that ground sloths went extinct around 11,000 years ago, these once-splashy children’s prints were likely made between 23,000 and 11,000 years ago, Bennet said.

Humans Who Made the White Sands Footprints

Researchers have not yet been able to precisely date the majority of footprints at White Sands. Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The team isn’t certain what cultures the trackmakers belonged to or when exactly they lived. “We’re dating them on the basis of the coexistence with the animals, which have known extinction dates,” says Urban. The team estimates that many of the tracks were made between 15,500 and 10,000 years ago, during a period that overlaps with the widespread North American Clovis culture, as well as the later Folsom tradition. Both peoples were hunter-gatherers who lived in small groups and are known today for their distinctive tools. Characteristic flaked Clovis spearpoints have been found with the bones of megafauna such as mammoth, and smaller worked Folsom points are often associated with bison kill sites. The White Sands tracks indicate the people—whoever they were—follo stalked, harassed, and possibly hunted big game. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

All around the playa, in every direction, the paths of creatures from the past preserve very specific moments. Humans ran on the balls of their feet. Families of all species—people, mammoths, camels—traveled together. There is also other evidence of ancient life lying on the surface. When Bonnie Leno and Kim Charlie, sisters from Acoma Pueblo who work at White Sands as historians, visited, they immediately spotted what they thought was a grinding stone resembling those still used to smash corn or make jerky at Acoma today. “I’ve walked by here like forty times and I haven’t seen that,” says White Sands National Park Resource Program Manager, David Bustos. Bustos. “We’ve had geologists look at these rocks and tell us, ‘Oh no, they’re here naturally,’” adds Connelly. No one else had identified what Leno and Charlie saw.

The two sisters say that when they visit a cultural site, they think of how their people live today, how their grandparents lived, and how the Ice Age trackmakers might have done things, too. “What were the women doing?” Charlie always asks. When they look across White Sands, they think it must have been a hunting ground with nearby campsites where the community gathered. “You see the footprints, you see children’s footprints,” Charlie says. “So you’ve got to think…” Leno finishes her sister’s thought: “…that was family.”

The team is further scouring the area, searching for the remains of hearths or other clues to how people lived, camped, and hunted in the area. They’ve also found perplexing grooves in the ground that might be related to the human tracks. “We’re not sure exactly what’s going on,” Connelly says, but the team suspects the people dragged something on a large stick. “We only see these where we see human footprints, so we just call them drag structures,” she adds.

After examining the grooves, Charlie and Leno think these abrasions could be additional evidence of hunting. “You take down the mammoth, there’s no way you’re going to carry that big carcass on your back and take it home,” Charlie says. Perhaps, the sisters say, the marks were left by sleighs that hunters used to haul the meat of especially large prey.

The two also spotted a group of rocks situated in a near-circle that reminded them of sundials common in the Southwest. Across the region, Native populations have long looked to the sun, the moon, and stars to keep track of time. Leno wonders if, at some point, the rocks signified that people did something similar at White Sands.

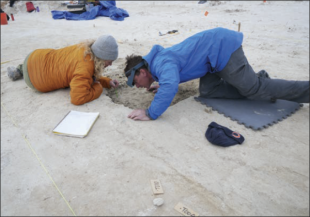

Studying the White Sands Footprints

Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The geological makeup of the area has preserved a wide variety of prints that allow scientists to discern an array of mammalian behaviors. “This gives us a rare window into a world that’s mostly lost to time and beyond our current reach,” Urban says. The length and breadth of the trackways at White Sands open a range of questions about early hunting practices, the lives of Ice Age species, and what the world was like when humans and Pleistocene megafauna shared this landscape. “Each of these trackways will have its own story to tell,” says Urban. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021]

Each day in the field is different for the research team, partly because weather conditions have to be just right in order to discern the tracks—too wet or too dry, and little is visible. For this reason, the White Sands prints are often called ghost tracks. “They can be very clear on the surface one day, and then another day, you can barely see anything,” Bennett says. “They’re quite mercurial.” That makes the work of identifying the trackways even more challenging. “It’s hard to orient yourself,” says Connelly, “because the site is never the same.”

Not only are the tracks difficult to identify, but one by one, the White Sands archive of Pleistocene life is steadily disappearing. Wind erodes the fine surface that covers the footprints and, once exposed, they quickly vanish. “We’re not sure if it’s climate change, or what’s happening,” Bustos says. “We’re losing them.”

The team is documenting trackways as rapidly as they can, using an array of tools to locate new prints and quickly gather information from those already identified. While erosion constantly exposes new trackways, the team also searches for those that are less visible. Urban has spent most of his time in the park conducting geophysical surveys using magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar, which allow researchers to create images of tracks that lie below the surface. The team then uses traditional tools to carefully remove sediments and expose the prints and record them. They make plaster casts and 3-D models of some of the tracks, though there are far too many to record them all in this way.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Ghost Tracks of White Sands archaeology.org

10,000-Year-Old 'Ghost Footprints' Found in the Utah Desert

In 2022, archaeologists announced they had found some "ghost footprints" in the salt flats of a Utah desert. They get their name because they become visible only after it rains and the footprints fill with moisture and become darker in color, before disappearing again after they dry out in the sun. Researchers accidentally discovered the unusual impressions in early July 2022 as they drove to an archaeological site at Hill Air Force Base in Utah's Great Salt Lake Desert. The team initially only found a handful of footprints, but a thorough sweep of the surrounding area using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) revealed at least 88 individual footprints belonging to a range of adults and children, potentially as young as 5 years old. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, August 2, 2022]

The ghostly prints were left by bare human feet at least 10,000 years ago when the area was still a vast wetland. However, researchers suspect that the tracks could date back as far as 12,000 years ago during the final stretch of the last glacial maximum ice age. Harry Baker wrote in Live Science: The Great Salt Lake Desert was once covered by a large, salty lake similar to the nearby Great Salt Lake — the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere — which the desert is named after. The ancient lake slowly dried up due to changes in Earth's climate triggered by the end of the last ice age, which left behind the salts that were once dissolved in the water. But during the transition from lake to dry salt flats, the area was briefly a large wetland that was occupied by humans up until 10,000 years ago, according to the statement.

People appear to have been walking in shallow water, with the sand rapidly infilling their print behind them, much as you might experience on a beach," lead researcher Daron Duke, an archaeologist with Far Western Anthropological Research Group, a private firm that specializes in cultural resources management, said in the statement. "But under the sand was a layer of mud that kept the print intact after infilling." The footprints have since been filled in with salt as the wetlands dried out, making them indistinguishable from the surrounding landscape when they're dry, Duke added.

Normally, when it rains, the water is quickly absorbed deep into the surrounding sediment, which means the ground quickly returns to its normal color. But when the rain falls on top of the hidden muddy footprints, the water gets trapped, creating patches of dark and wet sediment that stand out from their surroundings.

Less than a mile (1.6 kilometers) away from where the tracks were uncovered, a previous research group uncovered a hunter-gatherer camp dating to 12,000 years ago, where the humans who left the prints might have lived. Archaeological finds at the site included an ancient fireplace, stone tools used for cooking, a pile of more than 2,000 animal bones and charred tobacco seeds, which are the earliest evidence of tobacco use in humans.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, U.S. National Park Service, except Ghost prints in Utah from Science News

Text Sources: National Geographic, National Park Service, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024