EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF MODERN HUMANS IN THE U.S.

The oldest evidence of modern humans in the continental United States is a set of human footprints found at Lake Otero in White Sands National Park ,New Mexico that may date to 23,000 years ago. Stone, bone, and wood artifacts and animal and plant remains dating to 16,000 years ago in Meadowcroft Rockshelter, Washington County, Pennsylvania. (Earlier claims have been made, but not corroborated, for 50,000 year old sites such as Topper, South Carolina.) [Source: Wikipedia]

Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in Oregon has been dated 18,250 years old was described at “oldest human settlement in America in 2023. Before that Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, dated to be 16,000 years had previously thought to be the earliest inhabited site. Other very old sites in the lower 48 U.S. states include, 13,000-year-old Arlington Springs site on Santa Rosa Island in California. It was discovered in 1959. When sea levels were lower the four northern Channel Islands of California comprised one island, Santa Rosae.

The New Mexico footprints date to well before the peak of the ice age about 20,000 years ago. Some archaeologists question the New Mexico dates and the dates of some other places listed above, viewing evidence for human presence circumstantial and would prefer to see directly dated skeletons or genetics to confirm these dates. Some of the oldest directly-dated evidence of humans in the U.S. comes from Paisley Caves in Oregon, where researchers studied coprolites — preserved poop — to conclude they came from humans and were about 14,200 years old [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, July 15, 2023]

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: At the time the first Americans arrived “the earth was locked into a glacial period. Global temperatures were much lower than today, and many regions were covered with open grasslands that supported great herds of mammoth, bison and other large herbivores. Our ancestors made their living following these herds on their seasonal migrations, hunting the big animals with wooden spears tipped with sharp stone points. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 25, 2012 ***]

“About 12,000 years ago, the Earth's climate began to turn warmer and wetter. The dry grasslands gradually disappeared, giving way to immense tracts of dense forests. The great herds of grass-loving herbivores also disappeared along with their preferred habitat, and our ancestors shifted their lifestyles accordingly, taking up more intensive hunting and gathering patterns based on the newly emerging forests. Their favored hunting weapons changed from spears to bow and arrows. ***

“Sometime around 10,000 years ago, a new lifestyle emerged that would change the ecological equations forever. Until then, people had gathered a wide variety of edible wild plants. Now they realized that certain nutritious plants could actually be planted and grown. Thus was born agriculture. The productivity of the new crops was so great that farmers could grow a surplus beyond what was needed for their immediate families. ***

See Separate Articles:

WHITE SANDS FOOTPRINTS factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF HUMANS TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

WHEN AND HOW THE FIRST HUMANS CAME TO AMERICA: THEORIES AND EVIDENCE factsanddetails.com ;

MIGRATION ROUTE OF THE FIRST HUMANS IN AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

SINGLE WAVE VS MULTIPLE PULSE THEORY AND MIGRATION OF EARLY PEOPLE TO AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST AMERICANS: DNA, ASIA AND ASIANS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN WHAT IS NOW ALASKA AND CANADA factsanddetails.com ;

CLOVIS PEOPLE: SITES, POINTS, PRE-CLOVIS, MAMMOTHS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHERN SOUTH AMERICA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST HUMANS AND SETTLEMENTS IN THE AMAZON factsanddetails.com ;

SOLUTREAN HYPOTHESIS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas” By Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas (Twelve, 2022); Amazon.com;

“First Peoples in a New World: Populating Ice Age America” by David J. Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, (Cambridge University Press, 2021); Amazon.com;

“The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere” by Paulette F. C. Steeves (2023) Amazon.com;

“First Migrants: Ancient Migration in Global Perspective” by Peter Bellwood Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

"The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory" by Thomas D. Dillehay ( Basic Books, 2000 Dated) Amazon.com;

”Strangers in a New Land: What Archaeology Reveals About the First Americans”

by J. M. Adovasio, David Pedler (2016) Amazon.com;

“Paleoindian Mammoth and Mastodon Kill Sites of North America by Jason Pentrail (2021) Amazon.com;

“Clovis The First Americans?: by F. Scott Crawford (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Across Atlantic Ice: The Origin of America's Clovis Culture”

by Dennis J. J. Stanford, Bruce A. Bradley, Michael Collins Amazon.com;

“From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic—Paleo-Indian Adaptations (Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology) by Olga Soffer (1993) Amazon.com;

First Americans: A Rough Bunch?

James Chatters of Applied Paleoscience, a consulting firm in Bothell, Washington, Joel Achenbach wrote in the Washington Post, “believes that these early migrants were an aggressive breed — risk-takers and novelty-seekers. They chased wild game, including megafauna such as mastodons and saber-toothed cats, into unpopulated lands far from their ancestral hunting grounds. But later, as their descendants settled down and adopted agriculture, natural selection favored a gentler sort of personality, and men and women took on softer, more feminine features, Chatters argues. This tendency toward “neotony,” or natural selection of more childlike features, has been seen across much of the world, he said. [Source: Joel Achenbach, Washington Post, May 15, 2014]

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “By all appearances, the earliest Americans were a rough bunch. If you look at the skeletal remains of Paleo-Americans, more than half the men have injuries caused by violence, and four out of ten have skull fractures. The wounds don’t appear to have been the result of hunting mishaps, and they don’t bear telltale signs of warfare, like blows suffered while fleeing an attacker. Instead it appears that these men fought among themselves—often and violently. The women don’t have these kinds of injuries, but they’re much smaller than the men, with signs of malnourishment and domestic abuse. “[Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, January 2015 /~]

To Chatters “these are all indications that the earliest Americans were what he calls “Northern Hemisphere wild-type” populations: bold and aggressive, with hypermasculine males and diminutive, subordinate females. And this, he thinks, is why the earliest Americans’ facial features look so different from those of later Native Americans. These were risk-taking pioneers, and the toughest men were taking the spoils and winning fights over women. As a result, their robust traits and features were being selected over the softer and more domestic ones evident in later, more settled populations. /~\

“Chatters’s wild-type hypothesis is speculative, but his team’s findings are not.” Paleo-American skulls have “facial features typical of the earliest Americans as well as the genetic signatures common to modern Native Americans. This signals that the two groups don’t look different because the earliest populations were replaced by later groups migrating from Asia, as some anthropologists have asserted. Instead they look different because the first Americans changed after they got here.” /~\

The Heiltsuk Nation, located nearly 400 miles north of Vancouver, harvested herring roe on kelp forests, another important indigenous fishery. Without kelp off their shores, the Tla’amin harvested roe from deliberately submerged branches of Douglas fir or other trees—a practice that only died out with the herring run.” |*|

Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in Oregon (18,250-Years-Old) — Oldest Human Settlement in America?

Rimrock Draw Rockshelter outside Riley in eastern Oregon may be the earliest known human-occupied site in North America. Manufactured stone tools and fragments of animal teeth were found buried beneath layers of ash from an eruption of Mount Saint Helens that occurred thousands of years ago. Dating of tooth enamel from a now-extinct species of camel and bison indicates that humans inhabited the site more than 18,250 years ago, as much as 2,000 years earlier than they are known to have been at Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, previously thought to be the earliest inhabited site. “It's not so much that we have such old dates, but that we're getting consistent results,” archaeologist Patrick O’Grady, who led the excavation, told the Salem Statesman Journal, “This site is beautiful in that sense because … for the past 11 years, we're actually seeing something that's preserved through time that dates from about 7,000 years back to 18,000 years. And that's magic.” [Source: Abigail Landwehr, Salem Statesman Journal, July 8, 2023; Archaeology magazine, September-October 2023]

The Rimrock Draw Rockshelteris a 65-foot cleft in a basalt rim near an ancient, now-dry stream. There could be more-permanent dwellings in the area that archaeologists have not yet found. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists made the discovery at the site of Rimrock Draw, which includes a rock shelter that researchers have been excavating since 2011 under a partnership with the Bureau of Land Management. Initial investigations found stone tools from the Paleo-Indian period (15000 B.C. to 7000 B.C.), but the geology of the site suggested that there were sediment layers dating to even earlier. Although they expected to find old bones and artifacts, the archaeologists were startled by a stone tool with dried bison blood, which was discovered under a layer of volcanic sediment from the eruption of Mount St. Helens 15,400 years ago. This meant that humans were butchering ice age game in the Pacific Northwest far earlier than assumed. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, July 15, 2023] . Given this already surprisingly old date based on geological layers, the researchers decided to directly test some of the remains — including the tooth enamel of a Camelops, a now-extinct camel — to obtain solid dates. "We ran the first date on the Camelops tooth enamel in 2018," Patrick O'Grady, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon's Museum of Natural and Cultural History who led the research, told Live Science. When it came back with an extremely old date, he knew he would need additional proof.

O'Grady and his team took another sample from the camel tooth, as well as one from a bison tooth. When they were carbon-dated earlier this year, all of the dates agreed: Rimrock Draw was almost certainly used by humans 18,250 years ago. "Now that we have confirmation [of the date] plus additional support from a second sample, we feel comfortable with moving forward on the peer-reviewed article this fall," O'Grady said.

Paulette Steeves, an archaeologist at Algoma University in Canada who was not involved in the research, said Rimrock Draw is an interesting site. "Archaeologists that work on sites that are older than 11[,000] or 12,000 years are extremely careful with their dating and their work because of the historical pushback on older sites," she told Live Science.

Part of the Rimrock Draw publication will be focused on the dating methods used to produce the early date. Thomas Stafford, a geoscientist and founder of Stafford Research Laboratories who is involved in the research, told Live Science that "the enamel was easy to 14C date" because "mechanically, enamel dating is not complicated." Carbon-14 or radiocarbon dating is often considered the gold standard in archaeology; accurate for dates as far back as 60,000 years ago, the method measures the half-life or decay of carbon in organic remains.

Where it gets difficult, Stafford said, is in understanding the geology in which the sample was found; limestone can throw off the carbon dating of an enamel sample, making it too old, while too much rain or groundwater infiltrating a sample can make it seem younger than its true age. But Rimrock Draw is basalt, rather than limestone, and Stafford ruled out additional contamination because of the volcanic ash that protected the camel and bison bones. Repeated carbon dating over the span of five years and over different parts of the enamel helped Stafford confirm his findings. "I concluded the ages measured on camel and bison enamel were accurate and not affected by foreign carbonates younger or older than the teeth," he said.

Tools from Rimrock Draw Rockshelter

Jenny McGrath wrote in Business Insider: Ancient hunters used a rock-shelter in the Oregon desert to butcher camels, bison, mountain sheep, and horses during the Ice Age. In 2012 and 2015, archeologists found blood-stained stone tools buried below teeth from the extinct animals. "Ultimately, we think that the site was occupied for somewhere around 11,000 years, between about 7,000 and 18,000 years ago," O'Grady, staff archaeologist with the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, told Insider. [Source: Jenny McGrath, Business Insider, September 27, 2023]

The stone tools were below fragments of animal teeth, and both were covered by volcanic ash. The ash landed after Mount St. Helens erupted over 15,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dating revealed the tooth enamel on the Camelops and bison to be 18,250 years old. Since the tools were below the teeth, the researchers estimate they're at least as old, or older, than the 18,250-year-old teeth. It's basically like if you were to try and date the laundry in your laundry basket for the week, O'Grady said.

Two the tools are made of orange chalcedony, a type of quartz. "It's a really high-quality tool stone," O'Grady said. Right away, O'Grady and his colleagues were surprised to find that type of stone. "It didn't look familiar to anybody," he said. They determined the stone's place of origin was at least 50 to 75 miles away.

One tool they found in 2012 is a bit smaller than the size of a wallet with a rounded, rectangular shape. "It had three edges that had different kinds of flaking done to them," O'Grady said, a curved blade, a flatter side, and sawtooth edge. "You could easily hold the thing and use all three of those different functioning edges," O'Grady said, like a multi-purpose tool or Swiss Army knife. The other tool is also orange chalcedony and is about 3 inches long and appears to be only lightly used. It may be a chipped-off piece of another tool.

The researchers tested the multi-tool and found bison blood on it. Newer tools researchers found at the site contained remnants of mountain sheep and horse blood. The blood and many camel and bison teeth fragments suggest people used the site as a place to butcher animals instead of as a full-time residence. "It was a camp that people came to from time to time, and especially when they were hunting," O'Grady said.

Cooper's Ferry, Idaho (16,000 Years Old)

Cooper's Ferry is a prehistoric settlement at the confluence of Rock Creek and the lower Salmon River in western Idaho. Between 2009 and 2018, archaeologists unearthed artifacts and remains — including animal bones, a hearth pit, pieces of charcoal, stone tools and flakes of rock shaved off during toolmaking — that indicated the site was occupied by humans between 16,000 and 15,000 years ago. The site also contained dozens of pinkie-sized, unfluted spearpoints and blades carved out of stone and teeth from an extinct species of horse. Unfluted means spearpoints are not grooved or ridged. This is typical of a weapon-making tradition known as the western stemmed point tradition, which is distinct from the Clovis point tradition. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

Scientists used radiocarbon dating to determine the age of artifacts. For a while Cooper’s Ferry was heralded as the oldest evidence of humans in the Americas. After the announcement of the findings at archaeological site’s discovery. Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: “People were present there at a time when large expanses of North America were covered by massive ice sheets, and big mammals such as mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, the giant short-faced bear, horses, bison and camels roamed the continent's Ice Age landscape. "The Cooper's Ferry site contains the earliest radiocarbon-dated archaeological evidence in the Americas," said Oregon State University anthropology professor Loren Davis, who led the study published in the journal Science in August 2019. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, August 30, 2019]

“Based on this evidence, people first lived at the site, which was situated south of the continental ice sheets present at the time, between about 16,600 and 15,300 years ago and returned to live there multiple times until about 13,300 years ago, Davis added. The oldest artifacts included four sharp stone flake tools used for cutting and scraping and 43 flakes of stone left over from making stone tools, as well as animal bone fragments and horse tooth fragments. Also found at the site were fire-cracked rock and food-processing evidence.

“The new findings bolster the hypothesis that people in the initial migration into the Americas followed a route down the Pacific coast rather than a route through an inland ice-free corridor as some scientists have argued. "Cooper's Ferry is located in the upper Columbia River basin. The Columbia River would provide the first Americans their first route to interior lands south of the continental ice sheets," Davis said. With headwaters in British Columbia, it is the biggest river flowing into the Pacific Ocean from North America, opening into the ocean near Astoria, Oregon. Years of excavations at Cooper’s Ferry site have revealed 65,000 artifacts, along with “a 14,200-year-old fire pit and a food-processing area containing the remains of an extinct horse,” the university of Oregon said.

"The people who occupied the Cooper's Ferry site pursued a hunting and gathering lifeway most likely as small groups of people, likely fewer than 25 people in a group, who made multiple movements each year to access key resources as they were available," Davis said. Certain stone projectile points, which would have been attached to the ends of spears or dart shafts, closely resembled examples found in northern Japan dating a bit earlier than at the Cooper's Ferry site, the researchers said. "We hypothesize that this may signal a cultural connection between early peoples who lived around the northern Pacific Rim, and that traditional technological ideas spread from northeastern Asia into North America at the end of the last glacial period," Davis said.

Cooper’s Ferry — Site of Oldest Known Weapons in Americas

Thirteen “razor sharp” stone dart tips uncovered in the Cooper’s Ferry area are “roughly” 15,700 years old, making them the oldest weapons ever found in the Americas, according to archaeologists at the Oregon State University. The “full and fragmentary projectile points” — which are very similar to arrowheads — are about 2,300 years older than any previously excavated, the university reported in a December 23, 2022 news release that accompanied an article published the same day in Science Advances.. “It’s one thing to say, ‘We think that people were here in the Americas 16,000 years ago’; it’s another thing to measure it by finding well-made artifacts they left behind,” anthropology professor Loren Davis said in the release. [Source: Mark Price, Idaho Statesman, December 27, 2022]

Mark Price wrote in the Idaho Statesman: The well-preserved points are an half-inch to 2 inches long and were found on “a terrace of the lower Salmon River of western Idaho. The dig site, about 220 miles north of Boise, was “traditional Nez Perce land” and home to a village known as Nipéhe, historians say. The land is today called the Cooper’s Ferry site and is controlled by the federal Bureau of Land Management, the university says. The projectile points were uncovered between 2012 and 2017, and the excavation site has since been recovered with soil, the university said.

Davis says the dart tips represent “technology of that time” are were likely “attached to darts, rather than arrows or spears, and despite the small size, they were deadly weapons.” “There’s an assumption that early projectile points had to be big to kill large game; however, smaller projectile points mounted on darts will penetrate deeply and cause tremendous internal damage,” he said in the release. You can hunt any animal we know about with weapons like these.”

In 2023, archaeologists excavating at Cooper’s Ferry said they had unearthed 14 stone projectiles with stems on their ends that date to some 16,000 years ago, making them the earliest such weapons to be discovered in North America. A team led by Davis discovered the points buried in two pits that appear to have been dug around the same time. According to Archaeology magazine: The points were found along with stone waste flakes, bone fragments, and simpler stone tools. “The pits are the size of medium-sized garbage cans,” says Davis. “Maybe they were using them to clean up a dwelling we haven’t found yet.” He notes, however, that the points seem to be in good condition. “Perhaps they were being stored in equipment caches and were intended to be used after people came back to the site,” he says. Another possibility is that the points were retired as part of a ritual. The points’ shape resembles that of stemmed projectiles found in northern Japan that date to around 20,000 years ago. This raises the possibility that the people at Cooper’s Ferry may have been using a technology that originated somewhere around the Asian Pacific Rim. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2023

Meadowcroft Rockshelter

The Meadowcroft rock shelters are a National Historic Landmark, located in southwestern Pennsylvania, that contain evidence of human occupation dating to 16,000 years ago. Situated on top of a yellow sandstone mountain with a massive rock overhang carved out by the flowing waters of nearby Cross Creek, he site was first discovered in 1955 by a farmer, who found a flint knife, flint flakes and burnt bones in a groundhog hole. Archaeologists led by Jim Adovasio of Mercyhurst University, began excavating at Meadowcroft Rockshelter in the mid-1970s uncovered a wide array of human artifacts, including stone tools, spearpoints and wooden instruments. The site is both close source to an important source fresh water and located high enough so they humans that lived there would have been safe from flooding. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

The Meadowcroft rock shelters holds the distinction of being the longest-occupied site in the Americas. Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: “People began camping there episodically as early as 16,000 years ago and continued visiting the shelter until the thirteenth century A.D. Adovasio terms it “a late-Pleistocene Holiday Inn,” adding, “it has never flooded, it’s high and dry, the overhang, prehistorically, was fairly large, and it’s well ventilated.” Several feet below the shelter’s opening is Cross Creek, where those setting up camp could easily have access to freshwater. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, August 11, 2014 -]

“A roof collapse 13,000 to 14,000 years ago trapped beneath it a wealth of material uncovered in excavations. Adovasio says roughly 700 pieces of stone, some of them tools made from jasper and chert were recovered from the deepest units at the site. There were 50 complete tools or large enough fragments to be recognizable implements. There were prismatic blades and straight-based points with lance-like tips. As opposed to the fluted ridges found on Clovis points, these were largely smooth on the sides. -

“More than 50 sequential dates were taken, primarily from charcoal found in hearths, to arrive at ages that Adovasio says are between 14,000 and 16,000 years old. He was confronted with criticism related to a lack of ancient plant and animal remains at the site, which some researchers say make it difficult to know what the people at Meadowcroft subsisted on. Adovasio, for his part, says that they were likely “broad-spectrum foragers,” relying on a combination of meat and plants for sustenance. Other critics hypothesize that there was natural contamination of his radiocarbon dates, for instance, from water leaching coal from below the archaeological deposits. Adovasio has refuted those concerns. “Minimally, if you took only the very youngest acceptable dates,” he says, “then people were there at the same time as Clovis folks, but with a different technology.” -

Clovis People

Laura Anne Tedesco wrote for the Metropolitan Museum: “As the Pleistocene, or Ice Age, was ending and the earth was drying out, there was a profound change in the environment across North America. Hunters in North America pursued large animals for food. Skilled at the task, these Americans left evidence of activities throughout much of the continent where many of their living sites and hunt sites are now known. Blackwater Draw in eastern New Mexico, which evidences human activity from about 9500 to 3000 B.C., is one of the most important of the early hunter locations. Large animals were attracted to it for water—water sources being productive places for hunting—and the weapons with which the animals were brought down were principally of stone. [Source: Laura Anne Tedesco, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2000, revised September 2007 \^/]

“Discovered in the 1930s, Blackwater Draw defined the then newly discovered Clovis culture of North America (ca. 9500 B.C.). The name Clovis is derived from the modern town near Blackwater Draw. Currently documented to be among the earliest inhabitants of the North American continent beginning around 11,500 years ago, the Clovis people probably initially migrated into Alaska from Siberia, crossing the 600-mile-wide corridor along the Bering Strait that was then dry due to water confined in massive glaciers.

Their migrations as big-game hunters led the Clovis down from Alaska, through Canada into the North American plains as they followed herds of steppe bison, mammoth, and horse. These animals reached extinction around the same time Clovis hunters were becoming established in North America; whether the animals' extinction was due to the efficiency and tenacity of Clovis hunters, concurrent climate change, or a combination of both, is debated.\^/

“The Clovis people hunted using exquisitely crafted spears made from stone. Elegant as well as useful, these spears are known also by the name Clovis. Found at Blackwater Draw, Clovis points were made by pressure flaking handsomely colored chert, agate, chalcedony, or jasper. These effective hunting tools and weapons are distinctively shaped. Bifacial (that is, flaked on both sides), they have a large central, or "channel," flake removed from the bottom. This detail has given them the name of fluted points, and they are peculiarly American. The fluted detail of the points would have allowed them to be more easily mounted onto split wooden spear shafts, and also probably increased their streamline and stability as implements that would have been hurled at formidable prey. Following Clovis, the Folsom complex (ca. 8500 B.C.) also produced an elegant fluted point, one with a longer channel flake. It too was used in the hunting of big game, primarily bison.\^/

“Clovis-like points have been unearthed across the United States, Canada, and Central America. They are remarkably similar despite the vast geographic territory where they have been found. Typically a singular type of artifact takes on unique regional characteristics. Clovis points do not appear to follow this archaeological convention, and it may have been because they were extremely effective hunting implements as well as items exchanged in long-distance trade networks. The finer raw materials used to fashion Clovis points were also occasionally traded across vast distances. \^/

See Separate Article: CLOVIS PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

Paisley Caves

Paisley Caves is a network of eight caves and rock shelters in the Summer Lake Basin, in south-central Oregon. They were carved out by the waters of an ancient lake — Lake Chewaucan — which has since dried up. Archaeologists first excavated the caves in the late 1930s and found fragments of obsidian and bone tools, animal bones, wooden artifacts and baskets. More recent archaeological work there revealed human coprolites, or fossilized feces, which enabled archaeologists to pinpoint human occupation to 14,500 years ago and figure out what they ate — mostly grasses, large birds and now-extinct giant bison. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

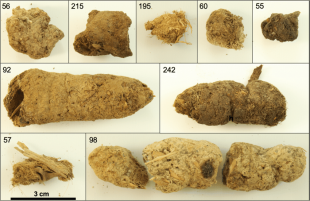

According to Archaeology magazine: “Stone tools and fire features are always great indicators of human activity at an archaeological site. And human bones are the best evidence excavators can hope to find. But humans also leave behind coprolites, or fossilized feces. Thanks to the extremely dry environment inside Oregon’s Paisley Caves, University of Oregon archaeologist Dennis Jenkins and his team came across five human droppings that dated to older than 14,000 years over the course of nine years of digging there. [Source: Archaeology August 11, 2014 */]

“In addition, they also found three points that Jenkins believes belong to what is known as the Western Stemmed tradition. Unlike Clovis points, which have a signature notch at their base so that wooden spears can be attached, these have constricted bases. They have also clearly been struck from smaller pieces of stone than the typical Clovis counterpart. Two human coprolites dated to just over 13,000 years ago were found within eight inches of one of the points. At the very least, this evidence suggests that there was a parallel occupation of the continental United States by both the Clovis people and a second group who made different types of tools.”

“Evidence of baskets and rope, plant fibers, wooden artifacts, and animal bones were also found at the caves. Pollen and other plant minerals extracted from the coprolites suggest that people came to the site in the spring and early summer. They also provide evidence that the people in the caves ate everything from edible roots to bison, horse, and even animals as big as mastodon. Jenkins, for his part, thinks Paisley Caves were not a destination location. “There is very little debitage [residue from production] from stone tools over time,” he explains. “The archaeology suggests this is a place where people are passing by—something, weather or resources nearby, or the time of day, makes you stop in.” */

Feces from Paisley Caves Offers Clues of Early Humans in America

Until recently, the record holder for oldest human coprolites (petrified shit) unearthed by archaeologists came from Oregon's Paisley Caves. Far older fecal samples from dinosaurs and ancient sharks have also been uncovered by researchers.

Based on analysis of the Paisley Cave coprolites, Dennis Jenkins, the University of Oregon archaeologist who led the excavation there, has been able to determine that the people there were gathering and consuming aromatic roots, for which they would have needed special knowledge that would have developed over time. “These guys aren’t the first people to come over the hills, see the caves, and go in there and relieve themselves,” he said. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2014]

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Perhaps ironically, the best evidence for a coastal migration might be found inland, as people traveling along the coast would likely have explored rivers and inlets along the way. There is already suggestive evidence of this in central Oregon, where projectiles resembling points found in Japan and on the Korean Peninsula and Russia’s Sakhalin Island have been discovered in a series of caves, along with what is surely the most indelicate evidence of pre-Clovis occupation in North America: fossilized human feces. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, January 2015 /~]

“In 2008 Jenkins reported that he’d found human coprolitesdating to 14,000 to 15,000 years old in a series of shallow caves overlooking an ancient lake bed near the town of Paisley. DNA tests have identified the Paisley Caves coprolites as human, and Jenkins speculates that the people who left them might have made their way inland from the Pacific by way of the Columbia or Klamath Rivers. /~\

“What’s more, Jenkins points to a clue in the coprolites: seeds of desert parsley, a tiny plant with an edible root hidden a foot underground. “You have to know that root is down there, and you have to have a digging stick to get it,” Jenkins says. “That implies to me that these people didn’t just arrive here.” In other words, whoever lived here wasn’t just passing through; they knew this land and its resources intimately.” /~\

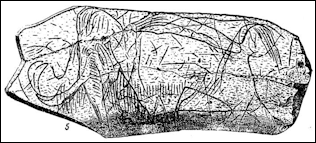

13,000-Year-Old Bone With Mammoth or Mastodon Carving Found in Florida

In 2011 Associated Press reported that a bone fragment at least 13,000 years old, with the carved image of a mammoth or mastodon, has been discovered in Florida, a new study reports. While prehistoric art depicting animals with trunks has been found in Europe, this may be the first in the Western Hemisphere, researchers report in the Journal of Archaeological Science."It's pretty exciting, we haven't found anything like this in North America," Dennis J. Stanford, curator of North American Archaeology at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, told AP. He was a co-author of the report. [Source: AP/The Huffington Post, June 22, 2011]

They hunted these animals, Stanford told AP and "you see people drawing all kinds of pictures that are of relevance and importance to them." "Much of the real significance of such finds is in the tangible, emotional connection they allow us to feel with people in the deep past," said Dietrich Stout, an anthropologist at Emory University in Atlanta, who was not part of the research team.

carved mammoth ivory from Florida The bone fragment, discovered in Vero Beach, Fla., contains an incised image about 3 inches long from head to tail and about 1 3/4 inches from head to foot. "There was considerable skepticism expressed about the authenticity of the incising on the bone until it was examined exhaustively by archaeologists, paleontologists, forensic anthropologists, materials science engineers and artists," lead author Barbara Purdy of the University of Florida said in a statement.

The bone was found by a fossil hunter near a location, known as the Old Vero Site, where human bones were found side-by-side with the bones of extinct Ice Age animals in an excavation from 1913 to 1916.It was heavily mineralized, which prevented standard dating, Stanford explained. But mammoths and mastodons had died out in the Americas by 13,000 years ago, so it has to be older than that. "It could be quite early," he added. But the researchers wanted to be sure it was not a modern effort to mimic prehistoric art. They compared it with other materials found at the site and studied it with microscopes, which showed no differences in coloration between the carved grooves and the surrounding material. That, they said, indicated that both surfaces aged together. In addition, the researchers said, there were no signs of the material being carved recently or that the grooves were made with metal tools.

"It either had to be carved from direct observation when the animals existed or has to be a modern fake" and "all indications are that the carving is the same age as the bone," said anthropologist Christopher J. Ellis of the University of Western Ontario, who was not part of the research team. The only other report of an ancient bone in North America carved with the image of a mastodon came from Mexico in 1959, but questions were raised about that object and it subsequently disappeared.

It does appear to be the first American depiction of a mammoth or mastodon, said anthropologist David J. Meltzer of Southern Methodist University."I think the authors did a reasonable job making the case for the piece being genuine," added Metzger, who was not part of the research team.

The discovery was made by James Kennedy, a fossil hunter, in 2006 or 2007. Kennedy noticed the image in 2009 when he was cleaning the bone and he then contacted researchers who began their study of the artifact. The newly found North American image is similar to some found in Europe, raising the question of whether this is merely coincidence or evidence of some connection between the two, the paper noted.

14,500-Year-Old Human Artifacts Found in Florida Sinkholes

Page-Ladson is an underwater archaeological site located at the bottom of a 30-foot-deep (9 meters) sinkhole in the Aucilla River, in northern Florida. The site is located just beyond the southeastern outskirts of Tallahassee. A former Navy SEAL accidentally discovered the site while scuba diving in the early 1980s, when he spotted bones belonging to an extinct species of proboscidean. Since then, archaeologists have uncovered stone tools and the remains of other extinct animals — including prehistoric camels, bison and mastodon — that date to 14,550 years ago. A mastodon tusk unearthed at the site bears cut marks that were probably made by humans, although it is unknown whether they butchered the animal or scavenged its remains. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 9, 2023]

mammoth

Guy Gugliotta wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “For much of its length, the slow-moving Aucilla River in northern Florida flows underground, tunneling through bedrock limestone. But here and there it surfaces, and preserved in those inky ponds lie secrets of the first Americans. For years adventurous divers had hunted fossils and artifacts in the sinkholes of the Aucilla about an hour east of Tallahassee. They found stone arrowheads and the bones of extinct mammals such as mammoth, mastodon and the American ice age horse. /[Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013 /||]

“Then, in the 1980s, archaeologists from the Florida Museum of Natural History opened a formal excavation in one particular sink. Below a layer of undisturbed sediment they found nine stone flakes that a person must have chipped from a larger stone, most likely to make tools and projectile points. They also found a mastodon tusk, scarred by circular cut marks from a knife. The tusk was 14,500 years old. /||\

“The age was surprising, even shocking, for it suddenly made the Aucilla sinkhole one of the earliest places in the Americas to betray the presence of human beings. Curiously, though, scholars largely ignored the discoveries of the Aucilla River Prehistory Project, instead clinging to the conviction that America’s earliest settlers arrived more recently, some 13,500 years ago. But now the sinkhole is getting a fresh look, along with several other provocative archaeological sites that show evidence of an earlier human presence in the Americas, perhaps much earlier. /||\

Stout said the suggestion that the similarities between this and ancient European art might imply some cultural contact or movement of people across the Atlantic very early is controversial. That idea has previously been proposed by Stanford and others, but has attracted a lot of criticism and skepticism from other archaeologists, he said. Metzger, too, said he doesn't "for a moment, think the specimen begs any questions about the larger issue of the peopling of the Americas. It's just one specimen - albeit an interesting one - of uncertain age and provenance, so one should not get too carried away."

Evidence of Human 14,500-Year-Old Mastodon Butchering Found in Florida

A team of archaeologists led by Jessi Halligan—an anthropologist who specializes in underwater archaeology at Florida State University has conducted an aquatic dig at Page-Ladson. William Herkewitz wrote in Popular Mechanics: “Halligan's team found stone knives and mastodon bones, tusks and dung, leading the scientists to believe the mastodon was either butchered or scavenged at the site by humans. Most interestingly, 71 individual radiocarbon dates show that the site is at least 14,550 years old—a full 1,500 years before many scientists recently believed humans first populated North America. The underwater dig was outlined today in the journal Science Advances. [Source:William Herkewitz, Popular Mechanics, May 13, 2016 +]

“This new find is important, because many archaeologists had long believed that 13,000-year-old stone spearheads and other remains found in the 1920s in Clovis, New Mexico, represented the first wave of human settlers in North America. "For over 60 years, archaeologists accepted that Clovis were the first people to occupy the Americas... Today, this viewpoint is changing," says Michael Waters, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University who's part of the team. "The Page-Ladson site provides unequivocal evidence of human occupation that predates Clovis by over 1,500 years." "For over 60 years, archaeologists accepted that Clovis were the first people to occupy the Americas... Today, this viewpoint is changing." +\

mastadon

“Halligan and her colleagues are not the first to root around in the waters of the Page-Ladson Archaeological Site, which is the "oldest [underwater] site yet discovered in the new world," Halligan says. "A recreational diver and a vocational archaeologist by the name of Buddy Page reported the site in the early 1980s to a team of paleontologists and divers... that team excavated this site for several seasons throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and made the amazing discovery of an adult mastodon tusk that appeared to have human-made cut marks. In the same geological layer, they found several possible stone artifacts," she says, as well as the remains of a dog. +\

“An initial round of radiocarbon dating—a method where scientists date material by observing the decay of carbon atoms in organic matter—was done in the early '90s and placed the age of the remains roughly 14,400 years ago. But back then, many assumed that date was a fluke and dismissed it. "It was an impossible age for the scientific community to accept at the time," says Halligan, because the resounding agreement was that the humans hadn't made it to North America until around 13,000 years ago.” +\

“Because the discovered mastodon dung "consisted of millions of fragments of chewed plant matter that was perfectly preserved, that allowed us to collect more than 70 radiocarbon samples from the site, she says. "All of the samples from this layer dated to more than 14,400 years ago and samples associated with the knife dated to 14,550 years old." In addition, Halligan's team confirmed that distinct markings on the tusks of the mastodon—a species that was hunted to extinction around 12,600 years ago—are chop marks from the stone tools. +\

“According to Waters at Texas A&M, the big takeaway is that these newly confirmed discoveries "contribute significantly to the debate over the timing and complexity of the peopling of the Americas in several ways." Since the 1990's, archaeology has seen a boon of newly discovered sites similar to Page-Ladson across North and South America, many of which have pushed back our understanding of when humans first entered the two continents. First, Page-Ladson is essentially the same age as the Monte Verde site in Chile and these two sites show that people were living in both hemispheres of the Americas by at least 14,500 years ago," Waters says. "Second, prehistoric people at Page-Ladson were not alone. [Other recent] archaeological evidence shows us that people were also present between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago in what are now the states of Texas, Oregon, Washington, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin."” +\

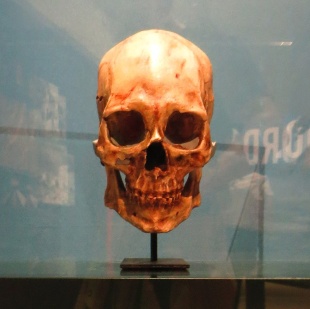

Kennewick Man

Kennewick Man refers to a complete skeleton of a 9,300-year-old man found in Kennewick, Washington. Douglas Preston wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “In the summer of 1996, two college students in Kennewick, Washington, stumbled on a human skull while wading in the shallows along the Columbia River. They called the police. The police brought in the Benton County coroner, Floyd Johnson, who was puzzled by the skull, and he in turn contacted James Chatters, a local archaeologist. Chatters and the coroner returned to the site and, in the dying light of evening, plucked almost an entire skeleton from the mud and sand. They carried the bones back to Chatters’ lab and spread them out on a table. [Source: Douglas Preston, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2014 /~/]

“The skull, while clearly old, did not look Native American. At first glance, Chatters thought it might belong to an early pioneer or trapper. But the teeth were cavity-free (signaling a diet low in sugar and starch) and worn down to the roots—a combination characteristic of prehistoric teeth. Chatters then noted something embedded in the hipbone. It proved to be a stone spearpoint, which seemed to clinch that the remains were prehistoric. He sent a bone sample off for carbon dating. The results: It was more than 9,000 years old," making Kennewick Man “one of the oldest skeletons ever found in the Americas." Some scientists said that Kennewick Man had "apparently Caucasoid" features similar to those found on the skulls of Jomon people — early inhabitants of Japan. They suggested "Kennewick Man" may have descended from Jomon people or a common ancestors of the Jomon people.

Scientists did not begin a careful examination of the Kennewick Man skeleton until almost ten years after he was found. Then a team led by physical anthropologist Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution was given 16 days to examine the skeleton, in July, 2005 and February, 2006. “A vast amount of data was collected in the 16 days Owsley and colleagues spent with the bones. Twenty-two scientists scrutinized the almost 300 bones and fragments. Led by Kari Bruwelheide, a forensic anthropologist at the Smithsonian, they first reassembled the fragile skeleton so they could see it as a whole. They built a shallow box, added a layer of fine sand, and covered that with black velvet; then Bruwelheide laid out the skeleton, bone by bone, shaping the sand underneath to cradle each piece. Now the researchers could address such questions as Kennewick Man's age, height, weight, body build, general health and fitness, and injuries. They could also tell whether he was deliberately buried, and if so, the position of his body in the grave. Next the skeleton was taken apart, and certain key bones studied intensively. The limb bones and ribs were CT-scanned at the University of Washington Medical Center. These scans used far more radiation than would be safe for living tissue, and as a result they produced detailed, three-dimensional images that allowed the bones to be digitally sliced up any which way. With additional CT scans, the team members built resin models of the skull and other important bones. They made a replica from a scan of the spearpoint in the hip." /~/

In 2014, a long-awaited study on Kennewick Man, co-edited by Owsley, was published. “No fewer than 48 authors and another 17 researchers, photographers and editors contributed to the 680-page Kennewick Man: The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton (Texas A&M University Press), the most complete analysis of a Paleo-American skeleton ever done. The book recounts the history of discovery, presents a complete inventory of the bones and explores every angle of what they may reveal. Three chapters are devoted to the teeth alone, and another to green stains thought to be left by algae." On the importance of Kennewick Man, Owsely said, “You can count on your fingers the number of ancient, well-preserved skeletons there are” in North America. /~/

Life of Kennewick Man

Douglas Preston wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: There's a wonderful term used by anthropologists: “osteobiography," the “biography of the bones." Kennewick Man's osteobiography tells a tale of an eventful life, which a newer radiocarbon analysis puts at having taken place 8,900 to 9,000 years ago. He was a stocky, muscular man about 5 feet 7 inches tall, weighing about 160 pounds. He was right-handed. His age at death was around 40. Anthropologists can tell from looking at bones what muscles a person used most, because muscle attachments leave marks in the bones: The more stressed the muscle, the more pronounced the mark. For example, Kennewick Man's right arm and shoulder look a lot like a baseball pitcher’s. He spent a lot of time throwing something with his right hand, elbow bent—no doubt a spear. Kennewick Man once threw so hard, Owsley says, he fractured his glenoid rim—the socket of his shoulder joint. This is the kind of injury that puts a baseball pitcher out of action, and it would have made throwing painful. His left leg was stronger than his right, also a characteristic of right-handed pitchers, who arrest their forward momentum with their left leg. His hands and forearms indicate he often pinched his fingers and thumb together while tightly gripping a small object; presumably, then, he knapped his own spearpoints. [Source: Douglas Preston, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2014 /~/]

“Kennewick Man spent a lot of time holding something in front of him while forcibly raising and lowering it; the researchers theorize he was hurling a spear downward into the water, as seal hunters do. His leg bones suggest he often waded in shallow rapids, and he had bone growths consistent with “surfer's ear," caused by frequent immersion in cold water. His knee joints suggest he often squatted on his heels. I like to think he might have been a storyteller, enthralling his audience with tales of far-flung travels. Many years before Kennewick Man's death, a heavy blow to his chest broke six ribs. Because he used his right hand to throw spears, five broken ribs on his right side never knitted together...The scientists also found two small depression fractures on his cranium, one on his forehead and the other farther back. These dents occur on about half of all ancient American skulls; what caused them is a mystery. They may have come from fights involving rock throwing, or possibly accidents involving the whirling of a bola. This ancient weapon consisted of two or more stones connected by a cord, which were whirled above the head and thrown at birds to entangle them. If you don't swing a bola just right, the stones can whip around and smack you. Perhaps a youthful Kennewick Man learned how to toss a bola the hard way. /~/

“The most intriguing injury is the spearpoint buried in his hip. He was lucky: The spear, apparently thrown from a distance, barely missed the abdominal cavity, which would have caused a fatal wound. It struck him at a downward arc of 29 degrees. Given the bone growth around the embedded point, the injury occurred when he was between 15 and 20 years old, and he probably would not have survived if he had been left alone; the researchers conclude that Kennewick Man must have been with people who cared about him enough to feed and nurse him back to health. The injury healed well and any limp disappeared over time, as evidenced by the symmetry of his gluteal muscle attachments. There's undoubtedly a rich story behind that injury. It might have been a hunting accident or a teenage game of chicken gone awry. It might have happened in a fight, attack or murder attempt." /~/

“The food we eat and the water we drink leave a chemical signature locked into our bones, in the form of different atomic variations of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. By identifying them, scientists can tell what a person was eating and drinking while the bone was forming. Kennewick Man's bones were perplexing. Even though his grave lies 300 miles inland from the sea, he ate none of the animals that abounded in the area. On the contrary, for the last 20 or so years of his life he seems to have lived almost exclusively on a diet of marine animals, such as seals, sea lions and fish. Equally baffling was the water he drank: It was cold, glacial meltwater from a high altitude. Nine thousand years ago, the closest marine coastal environment where one could find glacial meltwater of this type was Alaska. The conclusion: Kennewick Man was a traveler from the far north. Perhaps he traded fine knapping stones over hundreds of miles. /~/

Although he came from distant lands, he was not an unwelcome visitor. He appears to have died among people who treated his remains with care and respect. While the researchers say they don't know how he died—yet—Owsley did determine that he was deliberately buried in an extended, prone position, faceup, the head slightly higher than the feet, with the chin pressed on the chest, in a grave that was about two and a half feet deep. Owsley deduced this information partly by mapping the distribution of carbonate crust on the bones, using a magnifying lens. Such a crust is heavier on the underside of buried bones, betraying which surfaces were down and which up. The bones showed no sign of scavenging or gnawing and were deliberately buried beneath the topsoil zone. From analyzing algae deposits and water-wear marks, the team determined which bones were washed out of the embankment first and which fell out last. Kennewick Man's body had been buried with his left side toward the river and his head upstream.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Paisley Cave coprolites from Researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024