DEVELOPMENT AND ECONOMIC RISE OF MODERN MALAYSIA

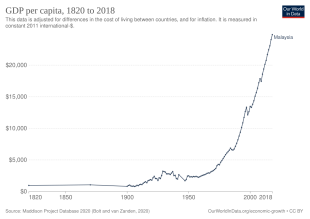

Before 1963, Malaya’s economy was fiscally sound, regularly producing balanced budgets or surpluses. After independence, Malaysia sustained rapid growth, averaging about 8 percent between 1975 and 1995, with GDP and per capita income rising sharply and poverty falling from around half the population in 1970 to about 7 percent by 2001. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

To address persistent ethnic and rural inequality, the government introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971. Its goals were to reduce poverty and to break the link between ethnicity and economic function by increasing Malay participation in the modern economy. Policies included rural resettlement, infrastructure development, education expansion, and state-led industrialization. These measures helped create a large Malay professional class and significantly increased Malay ownership of businesses and equity, though Chinese economic influence remained strong.

Economic growth was also driven by urbanization, oil and gas revenues, and industrial expansion, while poverty increasingly shifted to urban areas and lagging regions such as Sabah and Sarawak. Despite major economic transformation, political change lagged behind. Malaysia remained dominated by the UMNO-led National Front, with limited press freedom, restricted dissent, and continued use of emergency-era laws to constrain opposition.

RELATED ARTICLES:

COMMUNIST INSURGENCY IN MALAYSIA (1946-1989): ORIGINS, ACTIVITIES, POLITICS, ENDING IT factsanddetails.com

THE EMERGENCY IN MALAYSIA: DRACONIAN LAWS, NEW VILLAGES, ATROCITIES factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIAN INDEPENDENCE AND THE CREATION OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE LATE 1950s, EARLY 1960s: PART OF MALAYSIA OR AN INDEPENDENT STATE factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

RACIAL DISCORD IN MALAYSIA: RIOTS ON MAY 13, 1969, AFFIRMITIVE ACTION, BOAT PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

ELECTIONS IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: LEADERS, ETHNICITY, RELIGION, SYMBOLS, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL PARTIES IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD: HIS LIFE, VIEWS, CHARACTERS, OUTRAGEOUS STATEMENTS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER MAHATHIR MOHAMAD factsanddetails.com

ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS OF 1997-98 IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Challenges for the New Nation of Malaysia

After it became independent and sovereign in 1957 and 1963, Malaysia was immediately challenged by Indonesian hostility. Indonesia denounced Malaysia as a British imperialist creation and launched an undeclared conflict known as Konfrontasi. Malaysia relied heavily on military support from Britain and other Commonwealth countries, and hostilities continued until President Sukarno’s removal from power in 1965. The Philippines also opposed the federation, pursuing a diplomatic claim over Sabah until the late 1970s. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

The union with Singapore proved short-lived. Tensions arose between Malay political leaders and Singapore’s prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, whose efforts to advance the political position of the Chinese population clashed with Malaysia’s communal power-sharing arrangements. In 1965, Singapore separated peacefully from the federation.

Intercommunal tensions within Malaysia persisted and culminated in widespread violence in 1969, leading to the suspension of parliament for nearly two years. Political stability was later restored through the formation of the multiethnic National Front coalition. Tun Abdul Razak succeeded Tunku Abdul Rahman as prime minister in 1970 and introduced the New Economic Policy in 1971 to raise Malay economic participation through preferential measures. Following Abdul Razak’s death in 1976, Hussein Onn assumed the premiership.

Early Prime Ministers of Malaysia and Their Policies

Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra (1903-1990) was the leader of Malaysia's independence movement and the country's first prime minister. Known as “Bapa Malaysia” and the 20th son of the Sultan of Kedah, he the first premier of the Federation in 1957 and the premier of Malaysia in 1963. He negotiated independence with the British and maneuvered Malaysia through the bitter “Konfrontasi” with Indonesia over the absorption of Sabah and Sarawak. He resigned in 1970 after the Malay-Chinese riots in 1969. He was very critical of Mahathir, who he accused of being too authoritarian. Tunku Abdul Rahman studied in London after World War II.

Tun Abdul Razak was Malaysia’s second prime minister. He served from 1970 to 1976. He is regarded as the “Father of Development.” Tun Hussein Onn was Malaysia’s third prime minister. He served from 1976 until he retired in 1981. In 1971 Parliament reconvened, and a new government coalition, the National Front (Barisan Nasional), took office. This included UMNO, the MCA, the MIC, the much weakened Gerakan, and regional parties in Sabah and Sarawak. The DAP was left outside as the only significant opposition party. The PAS also joined the Front but was expelled in 1977. Tun Abdul Razak, implemented policies that strengthened Malay political dominance and enforced the Malay language more rigorously in education and the public sphere. Razak’s New Economic Policy (NEP) favored Malays. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

There was a period of centralized rule from 1969 to 1972. In 1972 UMNO created a partnership with the Pan-Malaysia Islamic Party (PAS) to reduce intra-Malay political differences and also renewed ties with the MCA, which had left the Alliance prior to the Kuala Lumpur riots. This broader, interracial coalition changed its moniker to the National Front (Barisan Nasional—BN) and won large majorities in the 1974 federal and state elections. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, BN administrations succeeded in increasing the power of the federal government relative to the state governments, often by forcing out of office independent-minded state chief ministers who were perceived as presenting a threat to national unity and ethnic accord. The BN also promoted educational policies designed for ethnic Malays and adopted aggressive measures to address economic inequalities experienced by Malays. [Source: Library of Congress, 2006]

Abdul Razak held office until his death in 1976. He was succeeded first by Datuk Hussein Onn, son of UMNO founder Onn Jaafar, and then by Tun Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad. Mahathir had been education minister since 1981 and held power for 22 years. During this time, policies were implemented that led to the rapid transformation of Malaysia’s economy and society. One such policy was the controversial New Economic Policy, launched by Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak, which aimed to proportionally increase the economic "pie" share of the bumiputras ("indigenous people," including the majority Malays but not always the indigenous population). Since then, Malaysia has maintained a delicate ethno-political balance with a system of government that attempts to combine overall economic development with political and economic policies that promote the equitable participation of all races. [Source: Wikipedia]

Elections and Political Parties in Young Malaysia

Before World War II, political activity in Malaya was limited, but the Japanese occupation and its aftermath fostered new political awareness. After the war, emerging political parties pressed for independence. Although Malays feared domination by the larger and economically stronger Chinese community, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) formed a power-sharing alliance with the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) in 1952, later joined by the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). This Alliance Party became the dominant political force. At the same time, the Malayan Communist Party, strengthened by wartime resistance, exerted strong influence in the trade unions until it was outlawed in 1948 after turning to armed struggle. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In the April 1964 general election, the Alliance won 89 of 154 parliamentary seats. Its position weakened in the May 1969 election, when it secured only 66 seats in peninsular Malaysia. The results were followed by serious communal riots, mainly between Malays and Chinese, leading to significant loss of life and property. Parliament was suspended under a state of emergency, and elections in Sabah and Sarawak were delayed until 1970. When parliament reconvened in February 1971, the Alliance had regained a two-thirds majority through unopposed seats from Sabah and a coalition with the Sarawak United People’s Party.

The 1969 elections also reduced Alliance control at the state level. In September 1970, Tunku Abdul Rahman retired as prime minister and was succeeded by Tun Abdul Razak. In 1973, the Alliance was expanded into the National Front (Barisan Nasional), incorporating UMNO, MCA, MIC, and several smaller parties. Dominated by UMNO, the National Front won successive elections in 1974, 1978, 1982, and 1986 by large margins. Mahathir Mohamad survived a narrow leadership challenge within UMNO in 1987.

Opposition parties remained weak, partly because electoral boundaries favored Malay-majority constituencies. The main opposition groups were the Democratic Action Party (DAP), drawing support largely from urban Chinese voters, and the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS), which sought to establish an Islamic state. By the 2004 elections, held after Mahathir’s retirement, UMNO and the National Front achieved their strongest mandate yet, securing more than 90 percent of parliamentary seats.

First Phase of Development in Malaysia: Exporter of Raw Materials

Malaysia had the fastest growing economy in Southeast Asia in the 1970s and 80s. In the 1970s, Malaysia was a young country with dependant on exporting raw materials such as timber, rubber, tin and palm oil. In 1970, commodities accounted for 70 percent of Malaysia's exports, while manufactured goods accounted for less than 30 percent. Resource-based industries in Malaysia have included rubber, timber, tin, palm oil, cocoa, silica, sand and clay. In the 1970s, Malaysia had a significant unemployment problem. Young workers lined to get jobs on rubber and palm oil plantations.

In the postwar era, many less-developed countries adopted formal development plans—typically five-year plans—to set priorities, targets, and funding requirements, and this approach was taken up across the Malaysian territories during the 1950s. Malaya moved earliest toward industrialization through an import-substitution strategy. The Pioneer Industries Ordinance of 1958 provided incentives such as five-year tax holidays, tariff protection, and guarantees allowing foreign investors to repatriate profits and capital. Early manufacturing focused on consumer goods, including batteries, paints, tyres, and pharmaceuticals. More than half of the investment capital came from abroad, with Singapore as the leading source. After Singapore left the federation in 1965, industrialization assumed greater importance for Malaysia, although foreign firms often complained that heavy bureaucracy slowed project implementation. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

Despite these efforts, primary production remained the backbone of the economy, particularly rubber, which faced the challenge of declining productivity. Much of the rubber stock dated back to the interwar period and was nearing the end of its economic life. Replanting with higher-yield varieties promised major gains but required a seven-year maturation period, which smallholders could not afford without assistance. To address this, the government introduced replanting grants funded by a special export duty on rubber. Progress was slow, and large-scale replanting was not completed until the 1980s. Many estates instead shifted to oil palm cultivation, which offered quicker returns. This transition proved highly successful, and by the 1960s Malaysia was supplying around one-fifth of global palm oil demand.

Improving the living standards of indigenous and rural populations was another priority. Land development schemes opened up large tracts of land, subdivided into smallholdings for land-poor farmers from densely populated areas. Beneficiaries received repayable financial assistance to cover housing and subsistence until their plots became productive. Rubber and oil palm were the main crops, complemented by measures to raise domestic rice output and reduce dependence on imports.

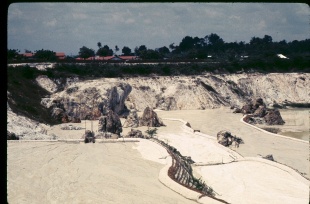

From the 1960s, Malaysia also diversified its primary exports through a rapid expansion of hardwood timber production, largely as unprocessed logs for markets in East Asia and Australasia. This growth drew heavily on the forest resources of Sabah and Sarawak, but the pace of exploitation later caused severe environmental damage and disrupted the livelihoods of forest-dwelling communities. Large infrastructure projects, including hydroelectric dams, produced similar ecological and social costs.

A further transformation came with the discovery of substantial oil and natural gas reserves in East Malaysia and offshore from the peninsula in the 1970s. Liquefied natural gas became a major export and a domestic energy source. At their peak in 1982, petroleum and LNG accounted for nearly 30 percent of export earnings, although their share declined later in the decade.

Development and Economic Rise of Modern Malaysia

In 1970, Malays made up about 75 percent of Malaysians living below the poverty line, were largely rural workers, and remained marginal to the modern economy. The government responded with the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971, implemented through four five-year plans (1971–90). Its two main goals were to reduce poverty—especially in rural areas—and to break the link between race and economic status, which implied shifting economic power toward Malays, who then accounted for only about 5 percent of professionals. [Source: Wikipedia]

Poverty reduction focused on agricultural resettlement, rural infrastructure, and the creation of free trade zones to generate manufacturing jobs. Some 250,000 Malays were resettled on newly cleared land, though little was done for low-paid plantation workers. By 1990, the poorest regions were Sabah and Sarawak. While rural poverty declined in the 1970s and 1980s, critics argue this owed more to overall economic growth—boosted by oil and gas discoveries—and rural–urban migration than to direct state intervention. Rapid urbanization, especially in Kuala Lumpur, drew migrants from rural Malaysia and neighboring countries, creating new urban poverty and shanty settlements.

A second pillar of the NEP, led largely by Mahathir Mohamad, aimed to expand Malay participation in the modern economy through education and state intervention. The expansion of Malay-language secondary schools and universities produced a large Malay professional class but also limited Chinese access to higher education, prompting many Chinese families to send students abroad. Educational opportunities for women expanded sharply, with women comprising half of university students by 2000.

To absorb new graduates, the state created major agencies such as PERNAS, Petronas, and HICOM, which employed Malays and steered investment toward sectors favoring them. As a result, Malay equity rose from 1.5 percent in 1969 to over 20 percent by 1990, and Malay ownership of businesses increased substantially, even if some firms remained indirectly Chinese-controlled. By 2000, ethnic distinctions in business were blurring in newer sectors like information technology.

Despite strong economic growth after 1970—interrupted only briefly by the 1997 Asian financial crisis—Malaysia’s political system changed little. Restrictive laws remained, elections were regular but dominated by the UMNO-led National Front, and opposition parties were fragmented. Media criticism and public protest were tightly constrained, with security laws continuing to be used against dissent.

New Economic Policy: Malaysia’s Affirmative Action Plan

The New Economic Policy (NEP) is an affirmative action plan implemented in the 1970s in response to the ethic riots of 1969 to counter the economic dominance of the country's ethnic Chinese minority and improve economic position of naive Malays. The policy has helped indigenous Bumiputras (native Malays, literally "sons of the soil") improve their positions by giving them preferential treatment in education, business and government, and setting quotas that limited the number of Chinese and Indians in universities and public jobs. Malays were given preferences in housing, bank loans, business contracts and government licenses.

The policy is backed by a special clause in the Constitution guaranteeing preferential treatment for Malays. It imposes a 30-percent bumiputra equity quota for publicly listed companies and gives bumiputras discounts on such things as houses and cars. Money is provided by banks and investment firms to Malays and indigenous people to start businesses. Businesses are required to have a bumiputra partner, who would hold at least a 30 percent equity stake.

The policy was introduced under Prime Minister Abdul Razak, the father of disgraced Prime Minister Najib Razak. It emerged in the aftermath of the 1969 racial riots, which were driven in part by Malay perceptions that ethnic Chinese dominated the economy. To address these imbalances, Razak designed an affirmative-action program aimed at raising the share of national wealth held by Malays and other indigenous groups to at least 30 percent. The policy provided Malays with preferential access to housing, university admissions, government contracts, and shares in publicly listed companies. [Source: Shamim Adam, Bloomberg, September 09, 2010]

See Separate Article: ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

Economic Impact of New Economic Policy 1970-90

The import-substitution industrialization (ISI) strategy lost momentum in the late 1960s as foreign investors—particularly from Britain—shifted their attention elsewhere. This slowdown coincided with rising political and ethnic tensions that culminated in the May 1969 riots, following a general election in which opposition parties, largely non-bumiputera, made unexpected gains. Long-standing disputes over issues such as the use of Malay (Bahasa Malaysia) as the national and educational language, and Malay perceptions that post-independence economic benefits had flowed mainly to non-Malays, especially the Chinese, came to a head. The violence, centered in Kuala Lumpur, led to the suspension of parliament for two years and the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP). [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

Implemented from 1970 to 1990, the NEP sought to restructure the economy with three main objectives: to increase bumiputera ownership of corporate equity from about 2 percent to 30 percent; to break the colonial-era link between race and economic function by aligning bumiputera participation in all sectors with their share of the population; and to eradicate poverty regardless of ethnicity. In 1970 nearly half of all households lived below the poverty line, with Malays comprising about three-quarters of the poor and heavily concentrated in low-income primary-sector employment.

The NEP was premised on redistribution through growth rather than zero-sum transfers. While agriculture continued to receive support, policy emphasis shifted decisively toward export-oriented industrialization (EOI). Free Trade Zones, notably in Penang, were established to attract foreign investment through tax incentives, duty-free imports, and relatively low labor costs. This strategy spurred the growth of manufacturing industries ranging from textiles and food processing to electronics, chemicals, and steel. As under ISI, foreign capital and technology remained central, exemplified by ventures such as the Proton national car project, developed with Japanese partners using largely imported components.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026