COMMUNIST INSURGENCY IN MALAYSIA

A Communist n insurgency to oust the British — the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) — began in World War II and was linked to the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and supported by China in the 1950s. The insurrection was a big part of the “Emergency.” It lasted for 12 years until 1960 and was led mainly by Chinese guerillas who worried they would be squeezed out an independent Malay state.

in Malaysia a Communist movement became a force to be reckoned with up after World War II and was very active in the 1950s. Based near Thailand, the group was made up mainly of Chinese loyal to Beijing. In its early years it was led by a mysterious figure named Loi Tek. No photographs of him was ever taken and few members of his own party ever saw him. He led the Malayan Communist Party from 1939 until his ouster in 1947. Rumors circulated that he was ousted because he embezzled funds and may have been a British double agent. Some believe he was killed in the 1940s. Others say he was still alive somewhere, living incognito, as of the 1980s.

The insurgency continued for more than a decade and was not put down until 1960. One British diplomat who dared to venture out of an barbed-wire enclosed compound for a drive in a place where Communists were never returned. His bullet-ridden body was found near a road. The Communists in Malaysia were marginalized by economic development and anti-insurgency tactics.

Government records show that at the height of the insurgency in the early 1950s, Malaya was home to some 40,000 British and Commonwealth troops, 70,000 police and a quarter of a million volunteer guards facing off 8,000 communist guerrillas. Several thousand civilians, insurgents and government troops were killed during the Emergency, according to colonial records, but historians are still divided over the exact number. The insurgency ended two years after Malaysia gained its independence from Britain in 1957 but the MCP continued fighting until a 1989 peace agreement was signed. [Source: Romen Bose, AFP, June 23, 2009]

Communist activity in Malaysia and worries about a domino effect in Southeast Asia played a part in the United States becoming involved in Vietnam. Marvin Ott, a professor of national security policy at the National War College, wrote in the Washington Post: "Trouble was building elsewhere throughout Southeast Asia. Malaysia, in addition to Indonesian hostility, faced a lingering guerilla movement that still dominated some of the remote jungle hinterland. Singapore...was embroiled in a fierce struggle between communists and Lee Kuan Yew's anticommunist People's Action Part in 1961-62.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

THE EMERGENCY IN MALAYSIA: DRACONIAN LAWS, NEW VILLAGES, ATROCITIES factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIAN INDEPENDENCE AND THE CREATION OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE LATE 1950s, EARLY 1960s: PART OF MALAYSIA OR AN INDEPENDENT STATE factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

Origins of the Communist Insurgency

After World War II, in 1945, the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was disbanded. in 1945, and the MCP initially operated as a legal political party, though its weapons were secretly stored. The MCP called for immediate independence and full racial equality, which attracted few Malays but gained strong support among Chinese trade unions and Chinese-language schools, especially in Singapore. In 1947, amid the growing Cold War, party leader Lai Tek was removed and replaced by Chin Peng, who shifted the MCP toward armed struggle. [Source: Wikipedia]

The communist-led MPAJA guerrilla force formed during World War II, was disbanded in December 1945 after the return of British rule. From it emerged the MNLA and Malayan Communist Party (MCP), which was allowed to operate briefly as a legal political party, while the MPAJA’s weapons were secretly retained. The MCP called for immediate independence and full equality for all races, a position that won little Malay support. As a result, its strength lay mainly among the Chinese population, especially in Chinese-dominated trade unions in Singapore and in Chinese schools, where many teachers—born in China—looked to the Chinese Communist Party as the leader of China’s national revival. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

The MCP itself had been founded clandestinely in 1930 under the direction of the Communist International, with Ho Chi Minh acting as Comintern agent for Southeast Asia. Although it initially sought to recruit Malays, Chinese, and Indians, by World War II it had become overwhelmingly Chinese. According to its 1934 constitution, the party aimed to overthrow British colonial rule, abolish Malay feudalism, and establish a Malayan People’s Republic. Before the war, it was already associated with acts of violence, including assassinations of British officials, police informers, political rivals, and internal dissidents.

In December 1941, following the Japanese invasion, the British formally recognized the MCP because of its willingness to resist Japan. Communist volunteers were trained by British officers and fought both alongside and behind Japanese lines. These fighters formed the core of the MPAJA, which was armed and supplied by the British throughout the war. After Japan’s defeat and the British reoccupation of Malaya in 1945, the MPAJA was dissolved, but the MCP continued as a legal political organization.

The transition from war to peace was marked by severe food shortages, labor unrest, and widespread strikes. The MCP actively supported workers’ protests, bringing it into repeated conflict with the British Military Administration. British troops frequently clashed with communist activists and, in some cases, used force to break up demonstrations and picket lines. In March 1947, as the Cold War intensified and the international communist movement shifted toward militancy, MCP leader Lai Teck was purged and replaced by Chin Peng, a veteran MPAJA guerrilla commander. Under Chin Peng’s leadership, the party increasingly embraced armed struggle, launching guerrilla operations aimed at forcing the British out of Malaya.

A separate but related communist insurgency emerged in Sarawak in the early 1960s. Chinese-led militants, influenced by communist ideas that had spread through Chinese schools since the 1940s and later through labor organizations, joined the Brunei uprising in December 1962 and cooperated with Indonesian forces during Indonesia’s Confrontation with Malaysia. In 1970, these insurgents formally established the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP). Communist influence had also penetrated Sarawak’s first major political party, the predominantly Chinese Sarawak United People’s Party (SUPP), founded in 1959.

Malaysia’s Communist Insurgency, Nationalism and Elections

The communist insurgency in Malaya was part of the global Cold War but also a national liberation struggle. Similar uprisings occurred in Malaya, Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines around 1948, as peoples across postwar Asia sought social justice, independence, and an end to European colonial rule. In this context, Malaysia’s first prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, acknowledged that Malayan communists also fought for independence, though he stressed that their movement was largely non-indigenous and aimed to establish a communist state unacceptable to Islam and democratic values. He described the conflict as a long and violent struggle that ended only when the British agreed to elections as a step toward independence. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

The insurgency left deep and lasting consequences. While it contributed to independence and nation-building, it also produced a prolonged Emergency, entrenched communal politics, and justified the use of authoritarian measures to combat subversion. Many of the security laws introduced during the Emergency remained in force long after the communist threat had ended, restricting civil liberties and slowing the growth of civil society. At the same time, efforts to counter the insurgency encouraged economic development, industrialization, non-aligned foreign policy, and more flexible multicultural policies. The insurgency thus shaped Malaysia’s political and social order in both constraining and constructive ways.

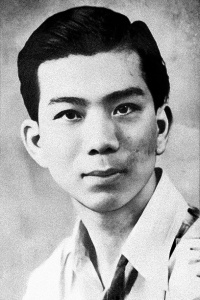

Chin Peng. Leader of the Malayan Communist Insurgency

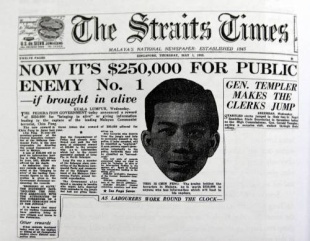

The ethnic Chinese, Malayan political activist and guerrilla leader Chin Peng fought both with the British and against them. For his exploits during World War II and he was appointed OBE, and after it he led the communist campaign to take over Malaya. According to The Guardian: Chin was the last of the major guerrilla commanders who fought colonialism in Asia after 1945, a group including Sukarno in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, Norodom Sihanouk in Cambodia and Aung San in Burma. [Source: Dan van der Vat, The Guardian, September 22, 2013]

Chin Peng (his nom de guerre) is said to have been born in 1924 in the Malayan state of Perak. His birth name was Ong Boon Hua and his father was an immigrant from China who set up a bicycle business. He took to politics at the age of 13, joining a new ethnic-Chinese society set up to send aid to China in its fight against Japanese aggression. His first role was to lead anti-Japanese activity at his school. At 16 he became a communist. In 1939 he transferred from his Chinese-language school to a British Methodist one, but left after six months to escape British domination and become a full-time revolutionary. To evade local British authorities he moved to Kuala Lumpur, the Malayan capital, in July 1940. When he attained full membership of the Communist party a year later, he was already serving on a number of party committees in Perak as well as party labour organisations.

The Japanese invaded Malaya in December 1941, when he was the junior member of the triumvirate running the Perak state committee. His two senior colleagues were arrested by the Japanese early in 1943, leaving Chin in charge. He went back to Kuala Lumpur in a bid to contact the CP central committee, which appointed a new state secretary for Perak in his place – but the new man was arrested as well, leaving Chin in charge at the age of 19.It was down to him to make contact with a British commando unit operating in Perak in September 1943. Japan was now the enemy and Chin adopted the view that my enemy's enemy is my friend.

After the Japanese defeat in August 1945, the British colonial administration returned and Chin began plotting against it. A state of emergency was declared in June 1948 after the murders of three European planters, allegedly by Malayan CP members. Chin denied foreknowledge but the party was banned, and thousands of British servicemen fought his guerrillas in the jungle. Peace talks at Baling, near the border with Thailand, in the final days of 1955 foundered on the legal recognition of the Malayan CP and an amnesty for insurgents, and fighting continued.

Uniquely, the harsh British counter-insurgency campaign prevailed and by 1960 Chin withdrew, first to Thailand and at the end of the year to Beijing. The subsequent "confrontation" by Indonesia against the new state and local British forces also failed and was abandoned in 1966.

Urged on by the communist Chinese under Mao Zedong, Chin kept up the campaign against independent Malaya and then Malaysia, in which many thousands died. In 1970 and after, the guerrilla bases in Thailand succumbed to murderous factionalism and paranoia, with a succession of spy trials and executions over which the distant Chin in Beijing could not achieve control.

The 1989 peace agreement included a provision for Chin and his comrades to return to his native country, which was never honoured. He went into exile in southern Thailand, travelling to Singapore to lecture at the university. His application in 2000 to return was rejected by the Malaysian high court after five years; his appeal failed in 2008, on the grounds that he was unable to prove his citizenship through documents long lost.

Activities of the Communist Insurgency in Malaysia

In 1946 the British proposed reforms that would have granted citizenship to many Malayan Chinese, but strong Malay opposition forced their withdrawal. This reversal angered sections of the Chinese community, leading to protests, strikes, and eventually violence. In 1948 the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) redirected this unrest into a rural guerrilla war against British rule. The Emergency was declared on 18 June 1948 following the murder of three European estate managers at Sungai Siput in Perak, an incident that became a defining moment of the conflict. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia, Australian government]

During the early years of the Emergency (1948–51), communist guerrillas attempted to cripple the economy by sabotaging rubber estates and tin mines. By late 1951, however, the MCP abandoned this strategy, recognizing that economic destruction alienated the population and harmed workers’ livelihoods. Thereafter, the insurgents focused on armed struggle rather than economic sabotage, allowing Malaya’s economic recovery to gain momentum.

The Emergency imposed severe hardships on civilians, particularly estate workers, who faced curfews, food rationing, security searches, and forced relocations. The conflict also spread beyond rural areas, with assassinations targeting both European officials and local Asian leaders seen as supporting the British, including the killing of Penang legislator Dr. Ong Chong Keng in 1948.

A major turning point came in October 1951 with the assassination of British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney. His death shocked the colonial administration and prompted a stronger and more coordinated counterinsurgency effort under a new British government. This escalation ultimately weakened the MCP and set Malaya on the path toward stability and independence.

The Emergency

From 1948 to 1960, the British and Malayans fought "the Emergency" against a primarily Chinese communist guerrilla insurgency. The insurgency cost 11,000 lives before it was defeated. By the early 1960s, the British were eager to disengage from Singapore and their responsibilities in Borneo. In 1963, Malaysia was formed, consisting of Malaya, the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, and Singapore. Oil-rich Brunei opted out. However, relations between Malaya and Singapore soured due to ambiguities in the federation agreement. Following two serious racial riots in Singapore in 1965, Singapore was abruptly expelled from Malaysia. [Source: Diane K. Mau, Governments of the World: A Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Thomson Gale, 2006]

In July 1948, following a series of assassinations of plantation managers, the colonial government declared a State of Emergency, banned the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), and arrested hundreds of its members. The party retreated into the jungle and formed the Malayan People’s Liberation Army, numbering about 13,000 fighters, the vast majority of whom were Chinese.

The British blamed the unrest on communist subversion, while the MCP denied responsibility and argued that the Emergency was a deliberate effort by the colonial state and British capital to suppress labor activism. Nevertheless, the Emergency caught the MCP unprepared. Its leader, Chin Peng, later wrote that mass arrests forced the party to revive its wartime resistance network and take up arms again. British authorities, in contrast, claimed they had acted preemptively to forestall a planned communist uprising. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: THE EMERGENCY IN MALAYSIA: DRACONIAN LAWS, NEW VILLAGES, ATROCITIES factsanddetails.com

Peace Efforts and Weakening of the Malayan Communist Insurgency

The British combined military action with political and economic concessions to the Chinese community and strong efforts to mobilize Malay support against the communists. From 1949 onward, the insurgency steadily lost momentum, and recruitment declined. Although the communists assassinated the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney, in 1951, this use of terror further weakened their public support.

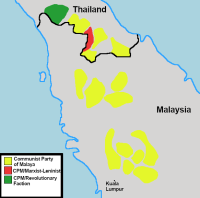

From the early 1950s, the Malayan Communist Party (CPM) suffered major military defeats, forcing its guerrilla forces to retreat to the Malayan–Thai border. Security force operations, British intelligence, and the Briggs Plan—by cutting insurgents off from food supplies—severely weakened the movement through heavy losses, shortages, and communication breakdowns. By 1960, according to Chin Peng, the CPM had been effectively routed and had quietly accepted military defeat as the Emergency ended. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

At the same time, British authorities sought to reduce communal tensions through the Communities Liaison Committee, which encouraged cooperation among ethnic leaders. These discussions helped foster a multi-ethnic vision of Malayan nationalism, though this approach proved politically contentious and led to divisions within UMNO and the eventual marginalization of leaders such as Dato’ Onn.

Following the Alliance Party’s overwhelming victory in the 1955 elections, the government offered amnesty to communist insurgents and opened negotiations with Britain for self-government. At the Baling Talks in December 1955, the CPM sought recognition as a legitimate political party and protection for its members, but these demands were rejected. Chin Peng then proposed ending the insurgency if the Alliance secured control over internal security and defence. Tunku Abdul Rahman accepted this challenge, strengthening the Alliance’s position in negotiations with Britain, which soon agreed to independence by 31 August 1957. Although the communists later claimed the Baling Talks accelerated independence, their subsequent request for renewed talks was rejected, and hostilities did not formally end.

Communist Insurgency After the Ending of The Emergency

Although the Emergency officially ended in 1960, the communist insurgency continued until 1989. As the CPM began demobilizing in late 1960, its leader Chin Peng fell ill and was sent to Beijing to recuperate and oversee the party’s final operations. He would remain there for the next twenty-nine years, and the party would not formally lay down its arms until 1989.In his memoirs, Chin Peng explained that the decision to continue armed struggle was shaped by advice from Vietnamese leaders in Hanoi, the escalation of the Second Vietnam War, and China’s Cultural Revolution, all of which encouraged a militant line among Asian communist movements. Consequently, the CPM intensified attacks, including ambushes of security forces, bombings of national symbols, and assassinations of police officers and political targets. What had begun as a struggle against British colonial rule was reframed as a war against “feudalists, comprador capitalists, and lackeys of imperialism.” [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

The Malaysian government responded with sustained vigilance. It devoted roughly one-third of the national budget to defence and internal security, retained British, Australian, and New Zealand troops and bases, and strengthened domestic security forces. Although the Emergency regulations were lifted in 1960, many repressive laws—such as detention without trial and censorship—remained in force. With external defence largely secured and communist forces confined to the Thai border, the government focused on national development, including education, rural development, and social welfare.

After independence, socialist parties such as the Labour Party and Parti Rakyat gained significant electoral support, especially in urban areas, and CPM cadres infiltrated these organizations. By the early 1960s, left-wing parties had won parliamentary seats and dominated local councils, prompting the Alliance government to suspend local government elections. At the same time, communalism and nationalism intensified, reinforced by fears of communist subversion.

The CPM’s strategy of open political struggle peaked in the mid-1960s with opposition to the formation of Malaysia, aligning itself with Indonesia’s confrontation policy. Left-wing parties across Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, and Brunei joined this campaign, but it failed. By 1966, the Labour Party had dissolved and other leftist groups were fragmented, suppressed, or in retreat, weakened by ideological divisions and mass arrests. International recognition of Malaysia and Singapore further discredited the CPM’s position. By the late 1960s, the party abandoned political struggle in favor of renewed militancy inspired by Vietnam’s “people’s war” and China’s Cultural Revolution, leading to further violent confrontations and repression.

Despite claims by Chin Peng that unrest attracted new recruits—particularly disaffected Chinese youths—the insurgency never became a racial conflict. Its primary threat remained its capacity to destabilize the state through terrorism. During the 1970s and 1980s, the CPM escalated attacks, including assassination of senior police officials and attempts to bomb national monuments. Internal factional rivalries within the CPM intensified violence as rival groups sought to demonstrate revolutionary commitment.

The communist threat reached a peak during the administration of Prime Minister Hussein Onn (1976–81), when allegations of communist infiltration within UMNO led to the detention of politicians and journalists. A major breakthrough occurred earlier, in 1973–74, when Sarawak Communist Organization leader Bong Kee Chok surrendered with 481 followers, representing the bulk of communist forces in the state. The remainder followed under a 1990 peace agreement.

Malaysia’s foreign policy shift under Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak (1970–76) further isolated the CPM. Razak abandoned overtly pro-Western alignment in favor of neutrality, promoted the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN), and joined the Non-Aligned Movement. Recognition of the People’s Republic of China—following Sino–US détente—undermined the CPM’s claim that Malaysia was a Western proxy. Razak’s discussions with Mao Zedong included calls for Beijing to end support for the CPM. Under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (1981–2003), further diplomatic engagement persuaded China to downgrade its ties with the CPM. This loss of external backing was a critical factor leading to the party’s eventual decision to end its armed struggle.

End of the Communist Insurgency in Malaysia and Its Legacy

The Communist insurgency was still active in the 1960s and 70s but ultimately was unable to recruit young people and eventually died out. The British perfected anti guerilla tactics in Cyprus, Malaya and Kenya. Village chiefs that supported insurgencies against the British and their allied governments were forced to frog march to prison.

According to Cheah Boon Kheng, factional splits within the CPM in Peninsular Malaysia led to the surrender of two merged factions comprising about 700 guerrillas to Thai forces in December 1987. By then, only around 1,300 fighters from the CPM’s 8th, 10th, and 12th Regiments remained active. On 5 November 1989, the Malaysian government disclosed that it had been engaged for nearly a year in talks with the CPM, the Thai military, and groups linked to the party. These negotiations culminated on 2 December 1989, when the CPM formally agreed to end its armed struggle and signed separate peace agreements with the Malaysian government and Thailand’s southern military commanders. The accord encouraged Sarawak-based guerrillas of the NKCP to surrender the following year. Six months later, Malaysian police confirmed that the CPM had fully complied with the agreement by surrendering and destroying its weapons and by assisting authorities in dismantling an estimated 45,000 booby traps along the Malaysian–Thai border. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

One of the central failures of the communist insurgency, Cheah argues, was its inability to integrate itself with nationalist forces. Unlike communist movements in China and Vietnam, which successfully recast themselves as nationalist struggles, the CPM failed to move beyond ideological militancy after independence. As a result, it became increasingly isolated from mainstream politics and appeared to be fighting primarily for ideological survival rather than national liberation. In both Malaya and Sarawak, the predominantly Chinese-led insurgencies sought to establish communist republics, but their reach remained limited. They did not develop into full-scale civil wars or ethnic conflicts, although the violence often assumed ethnic contours: a largely Chinese insurgency confronted mainly Malay security forces, while Chinese civilians and Malay police bore the heaviest casualties. Nevertheless, the insurgency indirectly contributed to the acceptance of a multiracial framework for independence by both British authorities and Malayan political leaders.

Despite the formal end of the insurgency, its legacy continues to provoke debate. In 2009, renewed attention focused on the communist past as Malaysian officials commemorated the assassination of British High Commissioner Henry Gurney, amid controversy over whether Chin Peng should be allowed to return from exile. While some political figures and supporters argued on humanitarian grounds that Chin Peng was an independence fighter, the government rejected his return following the dismissal of his final legal appeal. Veterans and victims of the insurgency strongly opposed any rehabilitation of his image, citing the human cost of communist violence. Historians have also questioned Chin Peng’s claim to hero status, noting his failure to acknowledge or apologise for the deaths caused by his movement and arguing that communist violence intensified fear, division, and confrontation during the transition to independence rather than facilitating it.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026