THE EMERGENCY AND THE COMMUNIST INSURGENCY

From 1948 to 1960, the British and Malayans fought "the Emergency" against a primarily Chinese communist guerrilla insurgency — the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA). The insurgency cost 11,000 lives before it was defeated. By the early 1960s, the British were eager to disengage from Singapore and their responsibilities in Borneo. In 1963, Malaysia was formed, consisting of Malaya, the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, and Singapore. Oil-rich Brunei opted out. However, relations between Malaya and Singapore soured due to ambiguities in the federation agreement. Following two serious racial riots in Singapore in 1965, Singapore was abruptly expelled from Malaysia. [Source: Diane K. Mau, Governments of the World: A Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Thomson Gale, 2006]

In July 1948, following a series of assassinations of plantation managers, the colonial government declared a State of Emergency, banned the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), and arrested hundreds of its members. The party retreated into the jungle and formed the Malayan People’s Liberation Army, numbering about 13,000 fighters, the vast majority of whom were Chinese.

The British blamed the unrest on communist subversion, while the MCP denied responsibility and argued that the Emergency was a deliberate effort by the colonial state and British capital to suppress labor activism. Nevertheless, the Emergency caught the MCP unprepared. Its leader, Chin Peng, later wrote that mass arrests forced the party to revive its wartime resistance network and take up arms again. British authorities, in contrast, claimed they had acted preemptively to forestall a planned communist uprising. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

The insurgency had far-reaching political effects. Several parties allied with the MCP in the multi-ethnic AMCJA–PUTERA coalition went underground, while others dissolved themselves, arguing that Emergency regulations made open political activity impossible. Although the guerrilla movement included small numbers of Malays and Indians—most notably in the MCP’s 10th Malay Regiment led by Abdullah C.D. and Rashid Mydin—it remained overwhelmingly Chinese.

The insurgents declared their immediate goals were to disrupt the colonial economy, establish “liberated” areas, and overthrow British rule in the name of national independence. In the early years, the MCP aligned itself with the multi-ethnic vision set out in the 1947 People’s Constitution for Malaya, temporarily moderating its aim of establishing a communist republic. In later decades, however, the party revised its position, rejecting the idea of Malays as the ethnic core of the nation, calling for full racial equality, and opposing Malay as the sole national language.

RELATED ARTICLES:

COMMUNIST INSURGENCY IN MALAYSIA (1946-1989): ORIGINS, ACTIVITIES, POLITICS, ENDING IT factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIAN INDEPENDENCE AND THE CREATION OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE LATE 1950s, EARLY 1960s: PART OF MALAYSIA OR AN INDEPENDENT STATE factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

Draconian Laws Aimed at Containing the Communist Insurgency

The communist insurgency fostered the rise of an authoritarian state in Malaya. In response to perceived communist subversion, the British administration introduced a range of draconian security laws, many of which continued to shape Malaysian governance after independence. These included the Emergency Regulations of 1948—elements of which were later absorbed into the Internal Security Act of 1960—as well as the Sedition Act (revised in 1969), the Societies Act (amended in 1981), the Official Secrets Act (amended in 1986), and the Essential (Security Cases) Regulations of 1975. Subsequent amendments strengthened the repressive character of these laws, granting the government wide powers to curtail civil liberties whenever national security was deemed at risk. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

During the Emergency (1948–1960), political life in Malaya was tightly constrained. Emergency regulations restricted freedom of movement, speech, and publication, and permitted detention without trial. Individuals suspected of communist sympathies or left-wing affiliations could be arrested, interrogated, or detained as collaborators. Newspapers required annual publishing licences, censorship was rigorously enforced, political parties and social organisations were subject to compulsory registration under the Societies Act, and public assemblies and demonstrations were banned. These measures were justified in the name of security and stability, but they effectively prevented the development of civil liberties and basic human rights during this period.

The 1948 Federation of Malaya Constitution further entrenched authoritarian rule. It neither guaranteed fundamental rights nor introduced democratic institutions such as universal suffrage, elections, or an elected legislature, granting only limited administrative participation to “Federal citizens.” Britain regarded the constitution as a temporary phase of political tutelage, yet for a population with little experience of democratic governance it coincided with the full force of emergency rule. By the end of 1949, more than 5,300 people had been detained, along with over 200 dependents; by late 1950, detainees numbered over 8,500. Throughout the Emergency, security forces dominated everyday life through checkpoints, patrols, mass screening operations, and an identity card system designed to monitor and control the population.

Foreign Military Presence in Malaysia During the Emergency

In 1950 the British appointed Lieutenant-General Sir Harold Briggs as Director of Operations in Malaya. His report laid the foundations of counter-insurgency strategy, advocating sustained anti-guerrilla operations, the isolation of insurgents from sympathetic communities, and a systematic military clearance of the country from south to north. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

By 1952, British and Commonwealth forces in Malaya had expanded to more than 32,000 regular troops, around three-fifths of whom were Europeans from the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. The remainder included Gurkhas, Fijians, the King’s African Rifles, seven battalions of the Malay Regiment, and Dayak jungle trackers from Borneo. These forces were supported by approximately 73,000 police—mostly Malays—and 224,000 Home Guards, also predominantly Malay, who served as village-based militias. Air force squadrons from Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, along with a small naval presence, complemented ground operations.

The financial burden of the campaign escalated rapidly, rising from about US$83,000 per day to over US$234,000 per day by 1953 and consuming roughly one-third of Malaya’s federal expenditure. Combined British and Malayan costs were estimated at US$1.4 million per week. These expenses were only sustainable because the Korean War triggered a sharp rise in rubber prices, significantly boosting Malaya’s revenues and underwriting the war effort.

Following the assassination of British High Commissioner Sir Henry Gurney in February 1952, Malaya was placed under a more overtly militarised administration led by General Sir Gerald Templer. Templer exercised near-dictatorial authority, ruling through fear and discipline, and was widely known for his abrasive manner and open hostility toward the Chinese community, whom he often associated collectively with communist insurgency.

Tough Tactics Used by General Gerald Templer

The appointment of Lieutenant General Sir Gerald Templer in 1952 marked a turning point. His tough and systematic counter-insurgency methods ultimately defeated the rebellion but not without costs. The Chinese community rallied behind the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) when it condemned General Templer’s official endorsement of Jungle Green, a book on the insurgency by Major Arthur Campbell that contained overtly racist depictions of the Chinese. Templer further alienated the community by imposing collective punishments in towns such as Permatang Tinggi, Tanjong Malim, and Pekan Jabi, confining residents to their homes for 24 hours and enforcing curfews for up to a week. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

The authoritarian character of Templer’s rule drew criticism even from The Times of London, which in October 1953 described Malaya as effectively a “police state.” The paper argued that Emergency regulations had vastly expanded executive power at the expense of individual liberties, creating what amounted to a military oligarchy sustained by surveillance and near-absolute security powers. It concluded that repression alone could not defeat communism and that greater political power had to be transferred to Malayans.

This critique soon resonated in London. The British government instructed Templer to introduce elections for an elected legislature and then recalled him, reassigning him to a military post in Germany. While Richard Stubbs later characterised Templer’s strategy as a balance of “carrot and stick,” the political reforms that constituted the “carrot” emerged largely because the “stick” had failed. Mounting financial costs, heavy casualties, and widespread social hardship convinced British policymakers that the insurgency could not be defeated without popular support. From 1951, Britain accelerated the transition to self-government, seeking to install a locally elected, non-communist government capable of prosecuting the war against the insurgents.

Harsh Tactics Used by the British During The Emergency

During the Malayan Emergency, British counterinsurgency operations against MNLA guerrillas frequently involved the detention, beating, and torture of villagers suspected of providing assistance. Chinese squatters in particular were routinely assaulted when they refused—or were unable—to provide intelligence. Some detainees and civilians were shot while attempting to flee or after declining to cooperate. Contemporary British commentary even defended such practices; The Scotsman praised them for undermining villagers’ belief in the invulnerability of communist leaders. In practice, however, arbitrary detention, collective punishment, and police torture fostered deep hostility among Chinese rural communities and ultimately undermined intelligence-gathering efforts. [Source: Wikipedia]

The centerpiece of British strategy was the Briggs Plan, under which nearly one million civilians—around ten percent of Malaya’s population—were forcibly removed from their homes. Tens of thousands of dwellings were destroyed, and displaced populations were confined in some 600 fenced and guarded “new villages,” widely likened to concentration camps. These measures aimed to isolate civilians from guerrillas and impose collective punishment on communities suspected of communist sympathies. Many evictions exceeded military necessity, involving the wholesale destruction of settlements, a practice prohibited under the Geneva Conventions, which restricts civilian internment to cases of absolute military necessity.

Collective punishment was applied systematically. At Tanjong Malim in March 1952, General Templer imposed a 22-hour curfew, shut schools, halted transport services, and cut rice rations for 20,000 residents. Medical experts from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine warned that such reductions threatened widespread illness and death among already undernourished civilians, particularly women and children. Similar measures were imposed at Sengei Pelek the following month, including a curfew, a 40 percent cut in rice rations, and expanded perimeter fencing, justified by officials as punishment for villagers’ alleged failure to cooperate and continued support for the MNLA.

In addition to internal displacement, the British authorities deported approximately 30,000 people—mostly ethnic Chinese—to mainland China during the conflict. Such deportations would constitute a violation of Article 17(2) of Additional Protocol II, which forbids the forced removal of civilians from their own territory for reasons connected to armed conflict.

Very few Chinese youths enlisted in the police or armed forces, occupations that were traditionally held in low esteem within Chinese society. By contrast, a Western scholar observed that the Malays overwhelmingly supported the government, enlisting in large numbers in both the Malay Regiment and the police. By mid-June 1957, Chinese civilian deaths numbered about 1,700, compared with 318 Malays, 226 Indians, 106 Europeans, 69 Orang Asli (Sakai), and 37 others. By the end of the Emergency, total casualties stood at 1,865 security personnel killed and 2,560 wounded, with civilian losses of roughly 4,000 killed and 800 missing; police casualties alone amounted to 1,346 killed and 1,601 wounded. Despite the disproportionately high Chinese civilian toll, the Malay press continued to question the loyalty of the Chinese community and its commitment to the campaign against the communist insurgency. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

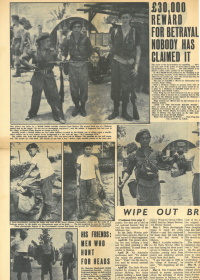

Displayed Corpses and Headhunting During The Emergency

During the Emergency, British and Commonwealth forces routinely displayed the corpses of suspected communists and anti-colonial guerrillas in public spaces, often in the centers of towns and villages. In some cases, local children were rounded up and compelled to view the bodies, with soldiers observing their reactions for signs of recognition or emotional attachment. Many of those whose corpses were exhibited had previously served as British allies during the Second World War. These practices were intended as psychological warfare but deepened fear and resentment within local communities. [Source: Wikipedia]

One prominent example was MNLA leader Liew Kon Kim, whose corpse was repeatedly displayed across British Malaya. At least two such incidents attracted significant attention in Britain and later became known as the “Telok Anson Tragedy” and the “Kulim Tragedy,” highlighting the extent to which these practices troubled public opinion at home.

British forces also recruited more than 1,000 Iban (Dyak) trackers from Borneo, valued for their jungle skills and headhunting traditions. Suspected MNLA members were decapitated, with authorities claiming that removal of heads was necessary for identification. British military leaders permitted Iban trackers to retain scalps as trophies. When these practices became public, the Foreign Office initially denied their use before attempting to justify them and manage press fallout. Privately, Colonial Office officials acknowledged that such actions would constitute a war crime under international law. Human remains linked to these practices were later found displayed in a British regimental museum.

In April 1952, the British communist newspaper Daily Worker (later Morning Star) published photographs of Royal Marines posing with severed heads inside a British military base. The images were circulated in an effort to mobilize domestic opposition to the war and further damaged the moral standing of Britain’s counterinsurgency campaign.

Batang Kali Massacre — Britain’s My Lai’

The most infamous atrocity of the Emergency was the Batang Kali massacre of December 1948, when members of the Scots Guards executed 24 unarmed male civilians near a rubber plantation at Sungai Rimoh, Selangor. The victims ranged from teenage boys to elderly men. Their village was subsequently burned, no weapons were found, and several bodies showed signs of mutilation. The sole survivor, Chong Hong, survived only because he fainted and was presumed dead. The British colonial authorities later conducted a cover-up that obscured the circumstances of the killings. Batang Kali became the subject of decades of legal action by victims’ families against the British government. Historian Christi Silver has noted the incident’s singularity, arguing that it was the only case of mass civilian execution by Commonwealth forces during the conflict, and attributing it to a distinctive regimental subculture within the Scots Guards combined with weak junior-level discipline. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ben Macintyre wrote in The Times, “On December 13, 1948, The Times ran a small news item in the Imperial and Foreign news section beneath the headline: “Forces’ success in Malaya”. That “success” was the killing of 24 Chinese villagers by a patrol of the Scots Guards at the height of the Malayan Emergency, the communist-backed insurgency against British colonial rule in what is now Malaysia. The incident remains one of the most controversial and mysterious episodes in British imperial history, but 64 years after the British soldiers opened fire deep in the Malay jungle, a court will finally rule on whether to open an official inquiry into the killings. [Source: Ben Macintyre, The Times, April 28, 2012]

In May 2012, lawyers representing families of the victims will present new evidence to the divisional court in London, claiming that the unarmed villagers were murdered in cold blood, and that the truth about the killings has been covered up ever since.The victims’ families say that there has never been a full investigation of an episode that has been described as “Britain’s My Lai” — a reference to the notorious killing of Vietnamese villagers by US forces during the Vietnam War.

In 1948, colonial authorities claimed that the 24 Chinese labourers in Batang Kali, a rubber plantation north of Kuala Lumpur, were suspected terrorists killed while attempting to escape. A brief, informal investigation of the incident was carried out in 1949, absolving the soldiers. But some of those involved later came forward to claim that they had given false accounts in order to ensure that the Guardsmen were exonerated. The colonial attorney-general overseeing that inquiry later called the episode “a bona fide mistake”. A second inquiry was launched in 1970, with a special Scotland Yard task team led by Frank Williams, the detective who played a key role in the Great Train Robbery investigation of 1963. That investigation was shelved by the incoming Conservative Government, ostensibly for lack of evidence.

At the time of the killings, British troops were battling a growing communist rebellion, principally by Chinese insurgents. A few days earlier, three British soldiers had been burnt alive by insurgents, and counter-insurgency forces had received reports of “bandit” activity in the area of the Batang Kali. On December 11 1948, a 16-strong unit of Scots Guards, mostly composed of inexperienced National Servicemen, surrounded the rubber estate at Sunga Rimoh by the Batang Kali river. The men were separated from the women and children. That evening one man was shot by the soldiers; the remaining 23 men were killed the next day. According to some reports, a few of the bodies were mutilated. The women and children were taken away and the village burnt. No weapons were found. Chin Peng, the leader of the Malayan National Liberation Army, has stated that no one in the village was linked to the communist insurgency.

The Batang Kali incident was initially hailed as an important victory against the rebels, but the revelations about the My Lai massacre in 1968 prompted closer scrutiny. In 1970, the People newspaper quoted one of the soldiers as saying: “Once we started firing we seemed to go mad . . . I remember the water turning red with their blood.” In 1992, a BBC documentary entitled In Cold Blood examined the case, but the Foreign Office insisted that no new evidence had been uncovered to warrant another official inquiry. Last September, the High Court ordered a full hearing into the case to rule on whether to launch an investigation. Quek Ngee Meng, co-ordinator of the Action Committee Condemning the Batang Kali Massacre, said that the decision to go ahead with legal hearings in this and the Mau Mau case sent an unequivocal message that there would be no cover-ups.

Rise of Communalism and Communal Politics

The colonial authorities were thus compelled to retreat from rigid hard-line policies and to encourage politics, elections, and a gradual move toward self-government. They could no longer prevent the formation of political parties of differing ideological orientations and were forced to allow greater freedom of political organization and activity. Coinciding with this shift, the outlawed Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) also revised its strategy. Under its October 1951 Directive, the CPM moved away from direct military confrontation toward political struggle, instructing its cadres to infiltrate legal political parties while concealing their communist affiliations. Communist agents selectively entered registered parties whose aims and programmes they deemed broadly acceptable. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

Over the next five to six years, socialist parties emerged and were likewise penetrated by communist cadres. Nevertheless, the political landscape came to be dominated by communal parties, which enjoyed an early advantage. Communal politics had been sharpened as early as 1948 during debates over the Federation of Malaya constitution, when Britain recast the federation as a nascent Malay state (Persekutuan Tanah Melayu). By abandoning the Malayan Union’s provisions for equal citizenship and restoring Malay rights and privileges, Britain provoked strong non-Malay opposition, though this resistance failed to gain lasting traction.

During the Emergency, non-communal and multi-racial parties—especially those associated with the left-wing AMCJA–PUTERA—were driven out of open politics. In their absence, communal parties such as UMNO, the British-sponsored Malayan Chinese Association (MCA, 1949), and the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC, 1946) came to dominate the political arena. As K. J. Ratnam observed, communalism arose not from prejudice but because prevailing conditions made it politically salient. These tensions were further exacerbated when thousands of able-bodied Chinese youths refused national service and departed for China in large numbers.

New Villages for Chinese Squatters

A key British strategy was to cut the insurgents off from their support base. Large numbers of ethnic Chinese were relocated from rural squatter settlements into government-controlled “New Villages,” which offered better health care and education while limiting contact with the guerrillas. Over time, the MRLA was pushed toward the Thai border, and by 1960 the Emergency was officially declared over.

During the early years of the Emergency, many Chinese squatters living along jungle fringes were forcibly removed and relocated to fenced “new villages” under government control. Initially, the British administration attempted to repatriate thousands of so-called “stateless” Chinese squatters, whom it suspected of supplying food and funds to communist insurgents. This policy failed when the newly established communist government in China closed its ports to foreign vessels, allowing only a few repatriation ships to land before the ban took effect. Those who had been sent abroad were eventually returned to Malaya. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

With repatriation no longer viable, the British adopted the Briggs Plan. Under this strategy, nearly half a million rural inhabitants—mostly Chinese—were uprooted and resettled in guarded camps or “new villages” to sever insurgents from civilian support. This massive population transfer profoundly altered Malaya’s demographic landscape, accelerating urbanization and concentrating Chinese communities in towns.

Before the Emergency, many Chinese were transient laborers unable to acquire land legally, since unalienated land in the Malay States was vested in the Malay Rulers and generally allocated to Malays. As a result, squatting on vacant land became widespread, driven by population growth, illegal wartime immigration, the collapse of mines and plantations, and the movement of urban residents into rural areas for food production. Between 1950 and 1960, some 480 new villages were established, relocating about 573,000 people—around 86 percent of them Chinese—mostly in western Peninsular Malaya.

These settlements were enclosed with barbed wire and guarded by police, leading critics to liken them to concentration camps, although they were equipped with basic amenities such as electricity, piped water, schools, and clinics. Parallel regrouping schemes affected another 650,000 people of various ethnicities in estates, mines, and factories, but unlike the new villages, Malay and Orang Asli settlements were generally not fenced. Attempts to relocate the Orang Asli into fortified zones largely failed.

The resettlement programme cost the British administration about M$100 million and created over 200 new urban centers. It significantly increased the proportion of Chinese in urban areas, strengthening their political presence in towns. At the same time, many Malays objected to the policy, arguing that the new villages enjoyed better facilities than Malay villages, despite Malay communities having shown stronger loyalty to the government during the Emergency.

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife — How the Malayan Insurgency was Stopped

“Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife” (a title taken from T.E.Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia) is a study of how the British Army succeeded in snuffing out the Malayan insurgency between 1948 and 1960 — and why the Americans failed in Vietnam. Tom Baldwin wrote in The Times: The thesis was written in Oxford by John Nagl, later a US Lieutenant Colonel and senior Pentagon adviser. It is was widely referred to by American military in the war in Iraq. [Source: Tom Baldwin, The Times, March 29, 2006]

Colonel Nagl was a Rhodes scholar at Oxford who served in the first Gulf War before returning to the university. At the time he was troubled by the conventional wisdom that the US's post-Vietnam doctrine of engaging in conflict only if it could use overwhelming force had been vindicated by Operation Desert Storm.

Instead, he believed, the swiftness of victory had shown future enemies the pointlessness of fighting the US through conventional means. "The Gulf War was a magnificent achievement by the American Army — and nobody will ever let us do it again," he said. "I concluded that our enemies would either go high-spectrum, and fight us with weapons of mass destruction, or low-spectrum and use the ancient arts of insurgency."

Colonel Nagl burrowed through the archives of the National Army Museum at Chelsea for the papers of Gerald Templer, the British commander in the now largely forgotten Malayan conflict. He was struck by how the British Army overcame initial setbacks by adapting to the "slow, messy and dangerous work" of countering insurgency with tactics he describes as "underwhelming force". Colonel Nagl believes that the British Army, lacking the US's resources, was "predisposed to innovation" and that the colonial experience made Sir Gerald more sensitive to local culture and advice. In contrast, by the time the US began adapting to the Vietcong's insurgency, it was too late.

His mission in Iraq, as a senior Pentagon adviser, wasis to ensure that the US learned quickly from its mistakes. An article, which Colonel Nagl co-authored for next month's Military Review, sets out some of the principles in a conflict where the primary goal is establishing a stable government in Iraq. Action that does not consider the political consequences "will at best be ineffective and, at worst, help the enemy", it says. "It is futile to mount an operation that kills five insurgents if the collateral damage leads to the recruitment of 50 more."

Sometimes the most useful reaction to provocation is to do nothing. Is the US learning to eat soup with a knife? "You're goddam right it is," he said, citing the example of training centres where they once prepared for tank battles, but that have now been turned into models of Iraqi villages filled with people speaking Arabic. Colonel Nagl spent a year conducting counter-insurgent operations near Fallujah, an experience he describes as "spilling soup on myself". Even Malaya took "12 years to resolve", he said, so no one should expect any sudden outbreak of peace and harmony.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026