WORLD WAR II IN MALAYSIA

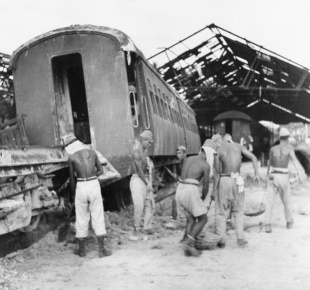

Japanese forces invaded Malaya peninsula and Borneo in early December 1941 and attacked Singapore on December 10, 1941. They quickly overran the peninsula. British defenses, built on the assumption of a seaborne attack, proved ineffective against a land invasion. By February 15, 1941, the Japanese occupied the Malay Peninsula and Singapore.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii was preceded by one hour by the Japanese invasion of the Malay peninsula. That operation was the first step in a drive to take Indonesia’s oil fields after the United States imposed an oil embargo on Japan. In terms of the number of people involved the Malay offensive was far larger than the attack on Pearl Harbor.

When war broke out in the Pacific in December 1941, the British in Malaya were completely unprepared. Although they had built a major naval base at Singapore during the 1930s in anticipation of the growing threat of Japanese naval power, they had never anticipated an invasion of Malaya from the north. Due to the demands of the war in Europe, virtually no British air capacity remained in the Far East. Thus, the Japanese were able to attack from their bases in French Indochina with impunity. Despite stubborn resistance from British, Australian, and Indian forces, the Japanese overran Malaya in two months. With no landward defenses, air cover, or water supply, Singapore was forced to surrender in February 1942, which did irreparable damage to British prestige. British North Borneo and Brunei were also occupied. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

COMMUNIST INSURGENCY IN MALAYSIA (1946-1989): ORIGINS, ACTIVITIES, POLITICS, ENDING IT factsanddetails.com

THE EMERGENCY IN MALAYSIA: DRACONIAN LAWS, NEW VILLAGES, ATROCITIES factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIAN INDEPENDENCE AND THE CREATION OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE LATE 1950s, EARLY 1960s: PART OF MALAYSIA OR AN INDEPENDENT STATE factsanddetails.com

Japanese Occupation of Malaya in World War II

The Japanese occupied Malaya in World War II from December 1941 to August 1945. The Chinese population suffered particularly harsh treatment there. Under Japanese administration, ethnic tensions between Malays and Chinese crystallized because Malays filled many administrative positions while the Chinese were treated harshly for their resistance activities and for supporting China’s war of resistance against the Japanese in the 1930s.

Just as the British did, the Japanese had a racial policy. They regarded the Malays as a liberated colonial people and fostered a limited form of Malay nationalism. This gained them some degree of collaboration from the Malay civil service and intellectuals. Most of the sultans in Malaya also collaborated with the Japanese, though they later claimed to have done so unwillingly. The Malay nationalist group Kesatuan Melayu Muda, which advocated for Melayu Raya, collaborated with the Japanese based on the understanding that Japan would unite the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, and Borneo and grant them independence. Although the Japanese argued that they supported Malay nationalism, they offended Malay nationalism by allowing their ally Thailand to re-annex the four northern states, Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu that had been surrendered to the British in 1909. The loss of Malaya’s export markets soon produced mass unemployment which affected all races and made the Japanese increasingly unpopular.

The Japanese occupiers regarded the Chinese as enemy aliens and treated them harshly. During the so-called Sook Ching (Purification Through Suffering), up to 80,000 Chinese people in Malaya and Singapore were killed. Chinese businesses were expropriated, and Chinese schools were either closed or burned down. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese, led by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), became the backbone of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). With British assistance, the MPAJA became the most effective resistance force in occupied Asian countries. [Source: Wikipedia]

Legacy of World War II

Future Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad wrote; “The success of the Japanese invasion convinced us that there is nothing inherently superior in the Europeans. They could be defeated, they could be reduced to groveling before an Asian race, the Japanese.”

During the Japanese occupation in World War II, exports of primary commodities were reduced to small amounts needed by the Japanese economy. Large areas of rubber plantations were abandoned, and many mines were shut down, increasingly affected by shortages of spare parts and equipment. Many businesses—especially those owned by Chinese—were taken over and transferred to Japanese control. Rice imports fell sharply, forcing much of the population to focus on growing enough food simply to survive. Large numbers of laborers were conscripted for military projects, including the construction of the Thai–Burma railway, where many died due to harsh conditions. [Source: John H. Drabble of the University of Sydney, 200]

World War II ordnance still kills people in Malaysia. In 2008, AFP reported: “Two foreign workers in a Malaysian scrapyard were killed when a World War II bomb exploded as they were cutting up the 100-kilogramme device, reports said. The victims, a Bangladeshi and an Indian man, died of their injuries shortly after the blast on Tuesday, which destroyed the scrapyard and a hostel located above it and blew out nearby windows, reports said. The scrapyard owner told the Star daily he had purchased the bomb, which had been found by a passerby in an open area just north of the capital Kuala Lumpur, not realising it was a piece of unexploded ordnance. [Source: AFP, August 20, 2008]

Malaysia After World War II

Within a year of the Japanese surrender in August 1945, the British established the Malayan Union, which consisted of the nine peninsular states, Penang, and Malacca. In 1946, Singapore and the two Borneo protectorates became separate British Crown colonies. On February 1, 1948, the Malayan Union was succeeded by the Federation of Malaya. Over the next decade, the British weathered a communist insurgency as Malaya progressed toward self-government. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

When the British resumed control of Malaysia after World War II in 1945, they sought to establish themselves as a durable administrative power. Ethnic tensions often influenced political arrangements. In 1946 the British formed the Malayan Union and made Sarawak and North Borneo into crown colonies and placed them under direct British rule. . The set up was much more like colonization that the protectorate system that had existed before. Many Malays objected to the system and the after seeing what the Japanese had done to them the British didn’t seem as all powerful as they once were.

Malaya was ‘Britain’s great dollar earner’. Its rubber and tin were precious assets as dollar earnings from the U.S. and Britain was reluctant to give up this source of wealth so quickly. After 1945, returning British authorities focused on two main goals: rebuilding the export economy and simplifying Malaya’s fragmented political administration. The export economy was largely restored by the late 1940s as mines and estates reopened, labor returned, and rice imports resumed. Administrative reform proved more complex. Britain began taking steps towards implementing Malaysian independence in 1948 when it realized the only way it was going to put down a communist uprising to get the support of the population with a promise of self rule. In 1948, the states of Malaya were forged into the Federation of Malaya and efforts were made to train the people who would run the government. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia]

In the transition from war time to peace, food shortages in Malaya led to public riots and to workers’ strikes and demonstrations for higher wages.. The Malayan Communist Party (CPM) supported these movements, bringing it into frequent and sometimes violent conflict with the British Military Administration. After civil government was restored, labor unrest intensified in 1947–48, coinciding with a political crisis caused by British constitutional reforms under the Malayan Union proposal, which offered no immediate path to self-government or independence. In 1948 a Communist insurgency erupted, lasting more than a decade. The guerrillas, largely drawn from the Chinese population, employed terrorist tactics. To counter the uprising, the British resettled nearly half a million Chinese in controlled communities. Although “The Emergency” was officially declared over in 1960, sporadic acts of terrorism continued thereafter. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press; Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

Britain's Plan for Malaysia After World War II

In January 1946, the British proposed the Malayan Union plan, which would place Singapore in one colony and combine the Federated and Unfederated Malay States with Penang and Malacca into a single new colony. Although the plan had been drafted in 1944 before the end of World War II, it was introduced soon after the war. It proposed easier citizenship for non-Malays and transferred the sovereignty of the Malay rulers to the British Crown. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore]

The proposal met fierce opposition from Malay leaders, who feared that granting citizenship to large Chinese and Indian populations in Pinang and Malacca would undermine Malay political dominance and the authority of the sultanates. Opposition to the Malayan Union led to the formation of the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) in March 1946, the country’s first major political party. Despite widespread resistance, the British implemented the Malayan Union on April 1, 1946. However, support for the Union from the largely Chinese Communist Party of Malaya raised British concerns about communist influence, prompting them to reconsider the arrangement.

Historian Cheah Boon Kheng has argued that the Malayan Union was essentially an attempt to merge the Malay States with Penang and Malacca into a centralized, British-governed unitary state. While Britain promoted equal citizenship for Malays and non-Malays in the name of unity and a shared “Malayan” identity, the plan denied self-government and stripped the Malay rulers of their authority. Rather than reducing colonial control, it strengthened British power through centralized administration, effectively amounting to annexation. Strong Malay opposition eventually forced the British to restore the powers of the Malay rulers and recognize special Malay privileges.

In response, the British abandoned the plan and replaced it with the Federation of Malaya. The British proposed a revised arrangement that retained the same territorial boundaries but created a federation with a Malay majority and greater autonomy over matters such as Malay customs and religion. This proposal worried many Chinese and Indian residents, while left-wing Malay and Chinese groups organized strikes in protest. Despite this opposition, the Federation of Malaya Agreement came into force on February 1, 1948. It was headed by a British high commissioner. and expanded the former Federated Malay States to include Penang and Malacca alongside the nine Malay states, but without a common citizenship. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Rise of Nationalism and the UMNO in Malaysia After World War II

During the Japanese occupation in World War II, ethnic tensions were raised and nationalism grew. The Malayans were thus on the whole glad to see the British back in 1945, but things could not remain as they were before the war, and a stronger desire for independence grew. Britain was bankrupt and the new Labour government was keen to withdraw its forces from the East as soon as possible. Colonial self-rule and eventual independence were now British policy. [Source: Wikipedia]

The tide of colonial nationalism sweeping through Asia soon reached Malaya. But most Malays were more concerned with defending themselves against the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) which was mostly made up of Chinese, than with demanding independence from the British – indeed their immediate concern was that the British not leave and abandon the Malays to the armed Communists of the MPAJA, which was the largest armed force in the country.

British plans for a Malayan Union described above was greeted with strong opposition from the Malays, who opposed the weakening of the Malay rulers and the granting of citizenship to the ethnic Chinese and other minorities. Mahathir Mohamad wrote: “I got together with my classmates and quietly we began agitating against the Malayan Union proposal. We were not allowed to be involved in political activity, so most of our work took place at night...We moved around the night putting up posters with political messages.”

In 1946 the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) was founded under the leadership of Dato’ Onn bin Jaafar to oppose the Malayan Union and promote Malay political dominance in an independent Malaya. The Malay federation proposal faced opposition from non-Malays and from some radical Malays who favored union with Indonesia. Left-wing Malay and non-Malay groups, including the Malayan Communist Party (CPM), formed the AMCJA–PUTERA coalition and presented an alternative constitution in 1947 calling for self-government, a fully elected legislature, democracy, and eventual independence. They also proposed a common Malayan nationality, Malay as the national language, and constitutional monarchy.

The British rejected these demands, as did UMNO and the Malay rulers, who were not yet ready to seek full independence. Amid rising labor unrest, violence broke out in mid-1948, including workers of European planters, marking a breakdown of law and order and paving the way for the communist insurgency.

The Emergency in Malaysia in the late 1940s and Early 1950s

Civil conflict followed the creation of the Federation of Malaya as the communists moved toward open rebellion. In July 1948, following a series of assassinations of plantation managers, the colonial government declared "The Emergency", banned the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), and arrested hundreds of its members. The party retreated into the jungle and formed the Malayan People’s Liberation Army, numbering about 13,000 fighters, the vast majority of whom were Chinese.

From 1948 to 1960, the British and Malayans fought "the Emergency" against a primarily Chinese communist guerrilla insurgency — the armed wing of the MCP known as the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA). The insurgency cost 11,000 lives before it was defeated. By the early 1960s, the British were eager to disengage from Singapore and their responsibilities in Borneo. In 1963, Malaysia was formed, consisting of Malaya, the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, and Singapore. Oil-rich Brunei opted out. However, relations between Malaya and Singapore soured due to ambiguities in the federation agreement. Following two serious racial riots in Singapore in 1965, Singapore was abruptly expelled from Malaysia. [Source: Diane K. Mau, Governments of the World: A Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Thomson Gale, 2006]

The British blamed the unrest on communist subversion, while the MCP denied responsibility and argued that the Emergency was a deliberate effort by the colonial state and British capital to suppress labor activism. Nevertheless, the Emergency caught the MCP unprepared. Its leader, Chin Peng, later wrote that mass arrests forced the party to revive its wartime resistance network and take up arms again. British authorities, in contrast, claimed they had acted preemptively to forestall a planned communist uprising. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132; Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: THE EMERGENCY IN MALAYSIA: DRACONIAN LAWS, NEW VILLAGES, ATROCITIES factsanddetails.com

Communists, Chinese and the Road to Independence in the 1950s

Opposition to the Malayan Communist Party among the Chinese community led to the creation of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) in 1949. The MCA represented moderate Chinese political views and was led by Tan Cheng Lock. He supported cooperation with UMNO to achieve independence based on equal citizenship, while making concessions to Malay concerns to reduce nationalist fears. Tan worked closely with Tunku Abdul Rahman, Chief Minister of Kedah and, from 1951, leader of UMNO.

After Britain announced in 1949 that Malaya would soon become independent, both leaders sought a political compromise their communities could accept. This led to the formation of the UMNO–MCA Alliance, later joined by the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC). The Alliance won decisive victories in local and state elections between 1952 and 1955, gaining strong support in both Malay and Chinese areas.

The introduction of elected local government also weakened communist influence. Following Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, divisions emerged within the MCP over continuing the armed struggle. Many members abandoned the insurgency, and by 1954 the Emergency had largely ended, although a small group under Chin Peng remained active near the Thai border for years. The conflict left deep and lasting tensions between Malays and Chinese. [Source: Wikipedia]

Between 1955 and 1956, UMNO, the MCA, and the British negotiated a constitutional settlement. It established equal citizenship for all races, while confirming key Malay interests: the head of state would come from the Malay sultans, Malay would be the official language, and Malay education and economic development would receive special support. In practice, Malays retained political dominance through control of the civil service, military, and police, while Chinese and Indians were guaranteed representation in government and protection of their economic interests. Disputes over education were postponed until after independence.

Tunku Abdul Rahman, UMNO Success and Negotiations with the Communists

After becoming leader of UMNO, Tunku Abdul Rahman formed an electoral alliance with the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) to contest municipal elections. The coalition won most local elections in 1952 and 1953 and was later expanded and formalized into a broader alliance that included the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC). This UMNO–MCA–MIC Alliance represented the three major ethnic communities in Malaya. [Source: Cheah Boon Kheng, National University of Singapore, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, 1 (June 2009): 132]

In July 1955, following the departure of Sir Gerald Templer, Malaya held its first general election. The multi-ethnic Alliance won an overwhelming victory, securing 51 of the 52 contested federal seats. Voters largely supported communal parties that they believed best protected their group interests, reinforcing communal politics. The Alliance formed the federal government, offered an amnesty to communist insurgents, and began negotiations with Britain for self-government and independence.

As part of the amnesty effort, Tunku Abdul Rahman met with Malayan Communist Party leaders at Baling, Kedah, on 28–29 December 1955. During the talks, Chin Peng stated that the communists would end their armed struggle if the Alliance government obtained control over internal security and defense from the British. Tunku accepted the challenge and promised to seek these powers from London. The talks received wide publicity and strengthened the Alliance’s position in negotiations with Britain.

Malaya achieved independence on 31 August 1957, with Tunku Abdul Rahman becoming its first prime minister. Eager to end the Emergency, the British agreed to transfer internal security and defense powers and accepted the goal of granting Malayan independence. Chin Peng later claimed that the Baling Talks accelerated independence, a view Tunku Abdul Rahman appeared to support when he later wrote that “Baling had led straight to Merdeka.” After independence, the communists requested another meeting, but this was refused.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026