SINGAPORE ATTAINS SELF-GOVERNMENT IN 1959

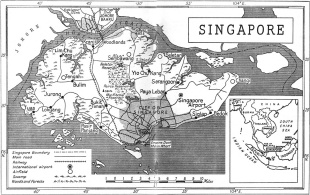

In 1959, Singapore was granted internal self-government by Britain as part of the Malaysian Federation. In May of that year, its first general election was held to elect fifty-one members to the fully elected Legislative Assembly. The People’s Action Party (PAP) won a decisive victory, securing forty-three seats with slightly more than 50 percent of the popular vote. On 3 June 1959, the new constitution establishing Singapore as a self-governing state came into force by proclamation of the governor, Sir William Goode, who became Singapore’s first Yang di-Pertuan Negara (head of state) from 1959 to 1961. The first government of the State of Singapore was sworn in on 5 June, with Lee Kuan Yew (1923–) assuming office as Singapore’s first prime minister.[Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The Lim Yew Hock government in the late 1950s continued to make further progress on issues related to Singapore's self-government. A Citizenship Ordinance passed in 1957 provided Singapore citizenship for all born in Singapore or the Federation of Malaya and for British citizens of two years' residence; naturalization was offered to those who had resided in Singapore for ten years and would swear loyalty to the government. The Legislative Assembly voted to complete Malayanization of the civil service within four years beginning in 1957. The Education Ordinance passed in 1957 gave parity to the four main languages, English, Chinese, Malay, and Tamil. By 1958 the Ministry of Education had opened nearly 100 new elementary schools, 11 new secondary schools, and a polytechnic school and set up training courses for Malay and Tamil teachers. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Lim Yew Hock led the Singapore delegation to the third round of constitutional talks in April 1958. The talks resulted in an agreement on a constitution for a State of Singapore with full powers of internal government. Britain retained control over foreign affairs and external defense, with internal security left in the hands of the Internal Security Council. Only in the case of dire emergency could Britain suspend the constitution and assume power. In August 1958, the British Parliament changed the status of Singapore from a colony to a state, and elections for the fifty- one-member Legislative Assembly were scheduled for May 1959. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL ACTIVITY IN PRE-INDEPENDENCE SINGAPORE: PAP, LEE KUAN YEW, COMMUNISTS, LABOUR FRONT factsanddetails.com

LEE KUAN YEW — SINGAPORE'S FOUNDER-MENTOR — AND HIS LIFE, VIEWS AND DEATH factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE UNDER LEE KUAN YEW factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

Malayanization Versus Independent Singapore

The People’s Action Party (PAP) initially came to power as part of a united front with communist groups in opposition to British colonial rule. Internal contradictions within this alliance soon became apparent, leading to a split in 1961. Pro-communist elements broke away to form a new political party, the Barisan Sosialis. At the same time, Malayan leaders emerged as key actors in the unfolding political drama, agreeing in 1961 to Singapore’s merger with Malaya as part of a larger federation. This proposed federation was also to include the British territories in Borneo, while Britain would retain control over Singapore’s foreign affairs, defence, and internal security during the transitional period. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Despite the signs of economic progress, the PAP leaders believed that Singapore's survival depended on merger with Malaysia. "Major changes in our economy are only possible if Singapore and the Federation are integrated as one economy," remarked Goh Keng Swee in 1960. "Nobody in his senses believes that Singapore alone, in isolation, can be independent," stated an official government publication that same year. The procommunists within the party, however, opposed merger because they saw little chance of establishing a procommunist government in Singapore as long as Kuala Lumpur controlled internal security in the new state. Meanwhile, the leaders of the conservative UMNO government in Kuala Lumpur, led by Tengku Abdul Rahman, were becoming increasingly resistant to any merger with Singapore under the PAP, which they considered to be extremely left wing. *

Moreover, Malayan leaders feared merger with Singapore because it would result in a Chinese majority in the new state. When a fiercely contested Singapore by-election in April 1961 threatened to bring down the Lee Kuan Yew government, however, Tengku Abdul Rahman was forced to consider the possibility that the PAP might be replaced with a procommunist government, a "Cuba across the causeway."

In the meantime, Indonesian leader Sukarno adopted a policy of Konfrontasi ("confrontation") against the Malaya federation, calling it a "British colonial creation," and cut off trade with Malaysia. This move particularly affected Singapore because Indonesia had been the island's second-largest trading partner. The political dispute was resolved in 1966, and Indonesia resumed trade with Singapore. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008.]

Singapore Becomes Part of the Federation of Malaya

On May 27 1961, the Malayan prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman (1903–1990) surprised everyone with his proposal for a union of Singapore with Malaya in a speech in Kuala Lumpur to the Foreign Correspondents' Association. He formally proposed closer political and economic cooperation through a merger involving the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, North Borneo, and Brunei. In this proposed Malaysia, the Malay population of Sarawak and North Borneo (now Sabah) would offset numerically the Singapore Chinese, and the problem of a possible "Cuba across the causeway" would be solved. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The principal terms, agreed upon by Abdul Rahman and Lee Kuan Yew, assigned responsibility for defence, foreign affairs, and internal security to the federal government, while granting Singapore autonomy in areas such as education and labour. A referendum held in Singapore on 1 September 1962 demonstrated overwhelming popular support for the PAP’s proposal to proceed with the merger.[Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

A referendum on the question of merger was held in September 1962. Of the three merger plans offered on the referendum, the PAP plan received 70 percent of the votes, the two other plans less than 2 percent each, and 26 percent of the ballots were left blank. The Federation of Malaysia was officially established on September 16 1963, comprising Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, and North Borneo (later renamed Sabah).

Objections to Singapore Becoming of the Federation of Malaya

Singapore, with its mostly urban Chinese population and highly commercial economy, found itself at odds with the Malay-dominated central government of Malaysia. The proposal for a Singapore and Federation of Malaya unionled almost immediately to a split between the moderate and procommunist forces within the PAP. In July 1959 Lee demanded and received a vote of confidence on the issue of merger from the Legislative Assembly. Following the vote, Lee expelled sixteen rebel PAP assemblymen from the party along with more than twenty local officials of PAP. In August the rebel PAP assemblymen formed a new opposition party, the Barisan Sosialis (The Socialist Front) with Lim Chin Siong as secretary general. The new party had considerable support among PAP local officials as well as at the grass-roots level. Of the fifty- one branch committees, thirty-five defected to Barisan, which also controlled two-thirds of organized labor. *

The battle lines were clearly drawn when Lee Kuan Yew announced a referendum. Lee launched a campaign of thirty-six radio broadcasts in three languages to gain support for the merger, which was opposed by the Barisan Sosialis as a "sell-out." Having failed to stop the merger at home, the Barisan Sosialis turned its efforts abroad, joining with left-wing opposition parties in Malaya, Sarawak, Brunei, and Indonesia. These parties were opposed to the concept of Malaysia as a "neocolonialist plot," whereby the British would retain power in the region.

President Sukarno of Indonesia, who had entertained dreams of the eventual establishment of an Indonesia Raya (Greater Indonesia) comprising Indonesia, Borneo, and Malaya, also opposed the merger; and in January 1963 he announced a policy of Confrontation (Konfrontasi) against the proposed new state. The Philippines, having revived an old claim to Sabah, also opposed the formation of Malaysia. The foreign ministers of Malaya, Indonesia, and the Philippines met in June 1963 in an attempt to work out some solution. Malaya agreed to allow the United Nations (UN) to survey the people of Sabah and Sarawak on the issue, although it refused to be bound by the outcome. Brunei opted not to join Malaysia because it was unable to reach agreement with Kuala Lumpur on the questions of federal taxation of Brunei's oil revenue and of the sultan of Brunei's relation to the other Malay sultans. *

Singapore as Part of Malaysia

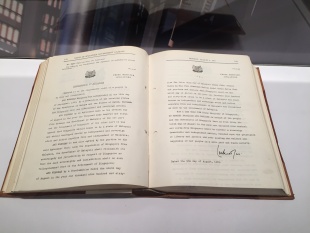

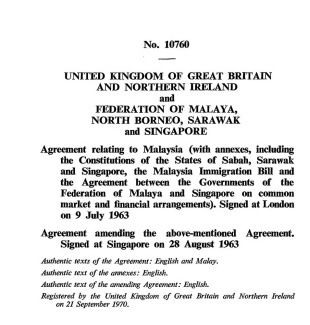

In 1963, Singapore achieved formal independence from Britain and joined the newly formed Federation of Malaysia. Between 1963 and 1965, Singapore was an integral part of the Federation of Malaysia. Union with Malaya had always been a goal of Lee Kuan Yew and the moderate wing of the PAP. Once the PAP ranks were firmly under Lee’s control, he met with the leaders of Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak to sign the Malaysia Agreement on July 9, 1963, under which the independent nation of Malaysia was formed.

On September 16, 1963, Singapore, the Malaysian peninsula and states of Brunei, Sabah and Sarawak on Borneo were united into one nation called the Federation of Malaysia. The sultanate of Brunei later broke away from the federation. Singapore remained part of Malaysia for two years. When it became clear that the interests of mainly-Chinese Singapore and mainly-Muslim Malaysia were different, the two countries parted ways. The split was for the most part amicable. The Republic of Singapore was officially created on August 9, 1965.

The leaders of Singapore, Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak signed the Malaysia Agreement on July 9, 1963, under which the Federation of Malaysia was scheduled to come into being on August 31. Tengku Abdul Rahman changed the date to September 16, however, to allow the UN time to complete its survey. On August 31, Lee declared Singapore to be independent with the PAP government to act as trustees for fifteen days until the formation of Malaysia on September 16. On September 3, Lee dissolved the Legislative Assembly and called for a new election on September 21, to obtain a new mandate for the PAP government. In a bitterly contested campaign, the Barisan Sosialis denounced the merger as a "sell-out" and pledged increased support for Chinese education and culture. About half of Barisan's Central Executive Committee, including Lim Chin Siong, were in jail, however, following mass arrests the previous February by the Internal Security Council of political, labor, and student leaders who had supported a rebellion in Brunei. The mass arrests, although undertaken by the British and Malayans, benefited the PAP because there was less opposition. The party campaigned on its economic and social achievements and the achievement of merger. Lee visited every corner of the island in search of votes, and the PAP won thirty-seven of the fifty-one seats while the Barisan Sosialis won only thirteen. [Source: Library of Congress *]

On September 14, the UN mission had reported that the majority of the peoples of Sabah and Sarawak were in favor of joining Malaysia. Sukarno immediately broke off diplomatic and trade relations between Indonesia and Malaysia, and Indonesia intensified its Confrontation operations. Singapore was particularly hard hit by the loss of its Indonesian barter trade. Indonesian commandos conducted armed raids into Sabah and Sarawak, and Singaporean fishing boats were seized by Indonesian gunboats. Indonesian terrorists bombed the Ambassador Hotel on September 24, beginning a year of terrorism and propaganda aimed at creating communal unrest in Singapore. The propaganda campaign was effective among Singapore Malays who had hoped that merger with Malaysia would bring them the same preferences in employment and obtaining business licenses that were given Malays in the Federation. When the PAP government refused to grant any economic advantages other than financial aid for education, extremist UMNO leaders from Kuala Lumpur and the Malay press whipped up antigovernment sentiment and racial and religious tension. *

The first year of merger was also disappointing for Singapore in the financial arena. No progress was made toward establishing a common market, which the four parties had agreed would take place over a twelve-year period in return for Singapore's making a substantial development loan to Sabah and Sarawak. Each side accused the other of delaying on carrying out the terms of the agreement. In December 1964, Kuala Lumpur demanded a higher percentage of Singapore's revenue in order to meet defense expenditures incurred fighting Confrontation and also threatened to close the Singapore branch of the Bank of China, which handled the financial arrangements for trade between Singapore and China as well as remittances. *

Race Riots in Singapore in 1964

The 1950s and 60s in Malaysia and Singapore were characterized by political battles between Chinese and Malays, violent race riots and street battles and a Communist insurgency that had racial and religious overtones. Singapore was embroiled in a fierce struggle between communists and Lee Kuan Yew's anticommunist People's Action Party.

There were two race riots in 1964. On July 21, 1964, fighting between Malay and Chinese youths during a Muslim procession celebrating the Prophet Muhammad's birthday erupted into racial riots, in which twenty-three people were killed and hundreds injured. In September Indonesian agents provoked communal violence in which 12 people were killed and 100 were injured. Frustrated Malay immigrants sparked the riots. In Singapore, which normally prided itself on the peace and harmony among its various ethnic groups, shock and disbelief followed in the wake of the violence. Both Lee Kuan Yew and Tengku Abdul Rahman toured the island in an effort to restore calm, and they agreed to avoid wrangling over sensitive issues for two years.

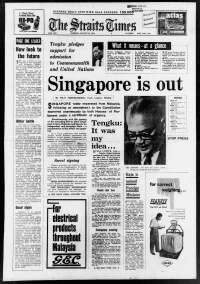

Singapore is Kicked Out of Malaysia

Soon after Singapore and the Malay Federation were joined, , political and ethnic tensions with the Malay-dominated federal government—rooted in Singapore’s predominantly urban Chinese population and its highly commercialised economy—soon surfaced. These differences ultimately led to Singapore’s separation from Malaysia in August 1965. Thereafter, Singapore emerged as a fully independent sovereign state within the British Commonwealth and, in December 1965, proclaimed itself a republic.

The exclusion of Singapore was largely due to Malay fears of Singapore's Chinese majority and its potential economic domination in the federation. Political tensions between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur escalated as each began getting involved in the politics of the other. UMNO ran candidates in Singapore's September 1963 elections, and PAP challenged MCA Alliance candidates in the Malaysian general election in April 1964. UMNO was unable to win any seats in the Singapore election, and PAP won only one seat on the peninsula. The main result was increased suspicion and animosity between UMNO and PAP and their respective leaders. In April 1965, the four Alliance parties of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak merged to form a Malaysian National Alliance Party. The following month, the PAP and four opposition parties from Malaya and Sarawak formed the Malaysian Solidarity Convention, most of whose members were ethnic Chinese. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Although the Malaysian Solidarity Convention claimed to be noncommunal, right-wing UMNO leaders saw it as a Chinese plot to take over control of Malaysia. In the following months, the situation worsened increasingly, with abusive speeches and writings on both sides. Faced with demands for the arrest of Lee Kuan Yew and other PAP leaders by UMNO extremists, and fearing further outbreaks of communal violence, Tengku Abdul Rahman decided to separate Singapore from Malaysia. Informed of his decision on August 6, Lee tried to work out some sort of compromise, without success. On August 9, with the Singapore delegates not attending, the Malaysian parliament passed a bill favoring separation 126 to 0. That afternoon, in a televised press conference, Lee declared Singapore a sovereign, democratic, and independent state. In tears he told his audience, "For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in merger and unity of the two territories." *

Singapore Becomes an Independent Nation

On August 9, 1965, Singapore left Malaysia to become an independent and sovereign democratic nation. On December 22, 1965, Singapore finally became an independent republic. Following independence, Singapore was admitted to the United Nations on September 21, 1965 and joined the Commonwealth of Nations on October 15, 1965. On December 22, 1965, it was proclaimed a republic, with Yusof bin Ishak (1910–1970) installed as the nation’s first president. Singapore was one of the founding members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967.

Lee declared Singapore’s independence from Britain on August 31, 1963; dissolved the Legislative Assembly; and called for an election to obtain a new mandate for the PAP pro-merger government. Many political opponents of the merger were jailed, and the PAP won a majority of seats in the assembly. Despite threats of military confrontation (Konfrontasi) from Indonesia and actual raids on Sabah and Sarawak by Indonesian commandos, the merger took place on September 16, 1963. In 1964, the British military withdrew from Singapore, leaving behind ports, roads, airports and other infrastructure projects that provided a firm foundation for their economy to take off.

Reaction to the sudden turn of events was mixed. Singapore's political leaders, most of whom were Malayan-born and still had ties there, had devoted their careers to winning independence for a united Singapore and Malaya. Although apprehensive about the future, most Singaporeans, however, were relieved that independence would probably bring an end to the communal strife and riots of the previous two years. Moreover, many Singaporean businessmen looked forward to being free of Kuala Lumpur's economic restrictions. Nonetheless, most continued to worry about the viability as a nation of a tiny island with no natural resources or adequate water supply, a population of nearly 2 million, and no defense capability of its own in the face of a military confrontation with a powerful neighboring country. Singaporeans and their leaders, however, rose to the occasion.

The new federation was based on an uneasy alliance between Malays and ethnic Chinese. Communal rioting ensued in various parts of the new nation, including usually well controlled Singapore. In the end, the merger failed. As a state, Singapore did not achieve the economic progress it had hoped for, and political tensions escalated between Chinese-dominated Singapore and Malay-dominated Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. Fearing greater Singaporean dominance of the federation and further violence between the Muslim and Chinese communities, the government of Malaysia decided to separate Singapore from the fledgling federation.

After separation from Malaysia on August 9, 1965, Singapore was forced to accept the challenge of forging a viable nation—the Republic of Singapore—on a small island with few resources beyond the determination and talent of its people. When Singapore became independent few thought it would survive for long Under the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP, the new nation met the challenge.

David Lamb wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Singapore, in fact, had so many problems on the eve of independence in 1965 that pundits predicted its early demise as a nation. A two-year federation with Malaysia had collapsed. The Chinese and Malay communities were at each others' throats. College campuses were roiled by leftist students. Communists had infiltrated the unions. A bomb claimed three lives in the inner city. On top of all that, Singapore had no army and was without resources or even room to grow. It had to import much of its water and food, producing little else beyond pigs and poultry and fruits and vegetables. Sewers overflowed in slums that reached across the island. Unemployment was 14 percent and rising; per capita income was less than $1,000 a year. [Source: David Lamb, Smithsonian magazine, September 2007]

British Involvement In Newly-Independent Singapore

Until Singapore's separation from Malaysia in August 1965, responsibility for national security matters had always resided either in London or Kuala Lumpur. In the two decades following the end of World War II (1939-45), Britain spent billions of dollars to rebuild its military bases in Singapore in order to honor its defense commitments to Malaysia and Singapore. Between 1963 and 1966, several thousand British troops were deployed to protect the two countries during the Indonesian Confrontation ( Konfrontasi). [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

By 1967 the British Labour and Conservative parties had reached a consensus that Britain could no longer afford to pay the cost of maintaining a military presence in Southeast Asia. In January 1968, London informed the Singapore government that all British forces would be withdrawn by 1971, ending 152 years of responsibility for the defense of Singapore. *

After the 1963 merger of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak to form the Federation of Malaysia, Singapore ceded control over its armed forces to the federal government in Kuala Lumpur. For a time, Malaysian army and air force units were stationed in Singapore, and Lee Kuan Yew's refusal to allow Malaysia to retain control over Singapore's military establishment after separation was one reason political relations between the two nations remained strained well into the 1970s.*

Indonesia's Destabilization Attempts in Singapore, 1963-66

Indonesia's opposition to the 1963 establishment of the Federation of Malaysia presented the only known external threat to Singapore since Japanese occupation. The opposition of Indonesian President Sukarno to the incorporation of Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo into the Federation of Malaysia set up the early stages of a low-intensity conflict called Confrontation, which lasted three years and contributed to Sukarno's political demise. In August 1963, Indonesia deployed several thousand army units to the Indonesian-Malaysian border on Borneo. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

Throughout the latter part of 1963 and all of 1964 the Indonesian army dispatched units, usually comprising no more than 100 troops, to conduct acts of sabotage and to incite disaffected groups to participate in an insurrection that Jakarta hoped would lead to the dissolution of the Federation. In June and July 1964, Indonesian army units infiltrated Singapore with instructions to destroy transportation and other links between the island and the state of Johor on the Malay Peninsula. Indonesia's Kalimantan Army Command also may have been involved in the September 1964 communal riots in Singapore. These riots occurred at the same time Indonesian army units were deployed to areas in Johor in an attempt to locate and encourage inactive communists in the Chinese communities to reestablish guerrilla bases destroyed by British and Malaysian military units during the Emergency.

After September 1964, Indonesia discontinued military operations targeting Singapore. In March 1965, however, a Singapore infantry battalion deployed on the southern coast of Johor was involved in fighting against a small Indonesian force that was conducting guerrilla operations in the vicinity of Kota Tinggi. Indonesia supported Singapore's separation from Malaysia in 1965 and used diplomatic and economic incentives in an unsuccessful effort to encourage the Lee administration to sever its defense ties with Malaysia and Britain. In March 1966, General Soeharto, who until October 1965 was deputy chief of the Kalimantan Army Command, supplanted President Sukarno as Indonesia's de facto political leader. Soeharto quickly moved to end the Confrontation and to reestablish normal relations with Malaysia and Singapore.*

Subversive Political Groups in Singapore in the 1960s, 70s and 80s

From 1965 to 1989, the government occasionally reported police actions targeting small subversive organizations. However, at no time were any of these groups considered a significant threat to the Lee government. From 1968 to 1974, a group known as the Malayan National Liberation Front carried out occasional acts of terrorism in Singapore. In 1974 the Singapore Police Force's Internal Security Department arrested fifty persons thought to be the leading members of the organization. After police interrogation, twenty-three of the fifty persons arrested were released, ten were turned over to Malaysia's police for suspected involvement in terrorist activities there, and seventeen were detained without trial under the Internal Security Act. One leader subsequently was executed in 1983 for soliciting a foreign government for weapons and financial support. The government alleged the Malayan National Liberation Front had been a front organization of the CPM, which in the late 1980s was still operating in the border area of northern Malaysia and southern Thailand. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

In 1982 a former Worker' Party candidate for Parliament and fourteen of his associates were arrested for forming the Singapore People's Liberation Organization. Zinul Abiddin Mohammed Shah, who had run unsuccessfully for Parliament in the 1972, 1976, and 1980 elections, was accused of distributing subversive literature calling for the overthrow of the government. Shah was tried and convicted on this charge in 1983 and was sentenced to two years in jail. His associates were not prosecuted.*

In 1987 twenty-two English-educated professionals were arrested under the Internal Security Act for their alleged involvement in a Marxist group organized to subvert the government from within and promote the establishment of a communist government. For reasons unknown, the Marxist group had no name or organizational structure. The government accused those arrested of joining student, religious, and political organizations in order to disseminate Marxist literature and promote antigovernment activities. Although twenty-one of the twenty-two persons arrested were released later that year after agreeing to refrain from political activities, eight were rearrested in 1988 for failing to keep this pledge. According to a 1989 Amnesty International report, two persons were being detained in prison without trial under Section 8 of the 1960 Internal Security Act. This number represented a significant reduction from the estimated fifty political prisoners held in 1980 (see Political Opposition, ch. 4).*

In January 1974, four terrorists belonging to the Japanese Red Army detonated a bomb at a Shell Oil Refinery on Singapore's Pulau Bukum and held the five-man crew of one of the company's ferry boats hostage for one week. The incident tested Singapore's capability to react to a terrorist attack by a group based outside the country and one having no direct connection with antigovernment activities. The counterterrorist force mobilized by the government after the bombing and hijacking comprised army commando and bomb disposal units and selected air force, navy, and marine police units.

Negotiations with the terrorists focused on the release of the hostages in return for safe passage out of the country. Apparently the government's primary consideration was to end the incident without bloodshed if at all possible. The Japanese government became involved when five other members of the Japanese Red Army attacked the Japanese embassy in Kuwait and threatened to murder the embassy's staff unless they and the four terrorists in Singapore were allowed to travel to Aden in the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen). Singapore refused to provide transportation for the terrorists but allowed a Japanese commercial airliner to land in Singapore, pick them up, and fly from Singapore to Kuwait. The hostages were released unharmed, and no deaths or serious injuries resulted from the incident.*

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026