JAPANESE INVASION OF THE MALAY PENINSULA

fighting in Malaysia

Singapore was the Japanese goal in Southeast Asia. On December 8, 1941, the day after the raid on Pearl Harbor, Japan invaded Malaya and began bombing Singapore. The Japanese overran the Malay peninsula in about eight weeks, advancing on bicycles across the Malay peninsula on excellent British-built roads while the British forces in Southeast Asia retreated to Singapore.

The Japanese easily captured British air bases in northern Malaya and soon controlled the air and sea-lanes in the South China Sea as far south as the Strait of Malacca. Naval landings were made on the Thai coast at Singora (present-day Songkhla) and Patani and on the Malayan coast at Kota Baharu. Also on December 10, the Japanese located and destroyed the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, thereby eliminating the only naval threat to their Malaya campaign. The Thai government capitulated to a Japanese ultimatum to allow passage of Japanese troops through Thailand in return for Japanese assurances of respect for Thailand's independence. This agreement enabled the Japanese to establish land lines to supply their forces in Burma and Malaya through Thailand. [Source: Library of Congress]

Malaya’s abundant natural resources made it an obvious target for Japanese militarists and industrialists. By 1939, the territory produced roughly 40 percent of the world’s rubber and 60 percent of its tin. This alone attracted Japanese interest, but two additional considerations decisively shaped invasion planning, which began in early 1941. First, the bulk of Malaya’s rubber and tin exports were destined for Japan’s potential transoceanic rival, the United States. Second, Japan faced a critical shortage of oil. Every drop consumed by its military and industry had to be imported, and the Imperial Japanese Navy alone required some 400 tons of oil per hour to remain operational. Although Malaya itself produced only limited quantities of oil, the peninsula offered an ideal base from which to launch and sustain operations against the oil-rich territories of Borneo, Java, and Sumatra. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com]

Japan’s strategic calculations were reinforced in June 1941 when the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands imposed embargoes on iron and oil supplies. This confirmed Japanese leaders in their belief that Southeast Asia had to be seized by force. Beyond resources, Malaya also figured prominently in Japan’s Outline Plan for the Execution of the Empire’s National Policy, which aimed to extend Japan’s defensive perimeter so far outward that enemy air forces would be unable to strike the home islands. This perimeter was envisioned to stretch from the Kuril Islands through Wake and Guam, across the East Indies, Borneo, Malaya, and northward to Burma.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

PEARL HARBOR, JAPANESE VICTORIES AND OCCUPATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com;

BEGINNING OF WORLD WAR II IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC factsanddetails.com;

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com;

JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR AND THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH factsanddetails.com;

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com INTERNED JAPANESE AMERICANS DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “World War II and Southeast Asia” by Gregg Huff Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 2, Part 2, From World War II to the Present” by Nicholas Tarling Amazon.com; “Malayan Campaign” by Hourly History and Matthew J. Chandler-Smith Amazon.com; “The Battle For Singapore: The true story of the greatest catastrophe of World War II” by Peter Thompson Amazon.com; “8 Miraculous Months in the Malayan Jungle: A WWII Pilot's True Story of Faith, Courage, and Survival” by Donald J. "DJ" Humphrey II Amazon.com; ”The Bridge Over the River Kwai” by Pierre Boulle, a classic novel that inspired the film Amazon.com; “The Second World War Asia and the Pacific Atlas (West Point Millitary History Series) by Thomas E. Griess Amazon.com; “The Pacific War, 1931-1945: A Critical Perspective on Japan's Role in World War II” by Saburo Ienaga Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com

Japanese Advance Quickly in Malaya

Japanese troops crossing a river

On December 8, Japanese troops of two large convoys, which had sailed from bases in Hainan and southern Indochina, landed at Singora (now Songkhla) and Patani in southern Thailand and Kota Baharu in northern Malaya. One of Japan's top generals and some of its best trained and most experienced troops were assigned to the Malaya campaign. By the evening of December 8, 27,000 Japanese troops under the command of General Yamashita Tomoyuki had established a foothold on the peninsula and taken the British air base at Kota Baharu. Meanwhile, Japanese airplanes had begun bombing Singapore. Hoping to intercept any further landings by the Japanese fleet, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse headed north, unaware that all British airbases in northern Malaya were now in Japanese hands. Without air support, the British ships were easy targets for the Japanese air force, which sunk them both on December 10. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The main Japanese force moved quickly to the western side of the peninsula and began sweeping down the single north-south road. The Japanese divisions were equipped with about 18,000 bicycles. Whenever the invaders encountered resistance, they detoured through the forests on bicycles or took to the sea in collapsible boats to outflank the British troops, encircle them, and cut their supply lines. Penang fell on December 18, Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942, and Malacca on January 15. The Japanese occupied Johore Baharu on January 31, and the last of the British troops crossed to Singapore, blowing a fifty-meter gap in the causeway behind them. *

The main Japanese force moved quickly to the western side of the peninsula and began sweeping down the single north-south road. The Japanese divisions were equipped with about 18,000 bicycles. Whenever the invaders encountered resistance, they detoured through the forests on bicycles or took to the sea in collapsible boats to outflank the British troops, encircle them, and cut their supply lines. Penang fell on December 18, Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942, and Malacca on January 15. The Japanese occupied Johore Baharu on January 31, and the last of the British troops crossed to Singapore, blowing a fifty-meter gap in the causeway behind them. *

Despite these ambitions, Japanese forces were ill-prepared for jungle warfare. Serious study of jungle combat did not begin until December 1940, and even then progress was limited. Responsibility for research was assigned to the Taiwan Army, despite the fact that Taiwan offered little suitable jungle terrain for realistic training. Japanese intelligence also significantly underestimated British and Commonwealth strength in Malaya, identifying only 30,000 to 50,000 troops when the actual number was closer to 88,600. Such miscalculation could have proven disastrous. Yet General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who was given overall command of the invasion, later remarked that “our battle in Malaya was successful because we took the enemy lightly.” [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com]

On paper, Yamashita commanded a force of 70,000 men organised into three divisions. In practice, Japanese strength was considerably lower. The 5th Division left an entire regiment behind in Shanghai as late as 26 December 1941, while the 18th Division retained two headquarters regiments in Canton. The Imperial Guard Division, though elite in training and discipline, had no combat experience.

British defences in both Malaya and Singapore were similarly unprepared. Coordination between ground forces and the small Royal Air Force contingent was poor, while many ground troops—particularly Indian conscripts—were inadequately trained and equipped. Senior British officers likewise lacked experience in jungle warfare, and some failed to appreciate its importance. Complaints that dense jungle left no room for manoeuvres reflected a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the conflict they faced. Although Singapore was publicly portrayed as a fortress capable of resisting amphibious assault, defences against a conventional advance down the Malayan Peninsula were weak. Another indication of unpreparedness was the absence of food rationing, despite Britain having been at war since 1939 and the likelihood of Japanese invasion becoming clear by late 1941. The most significant defensive measure seriously pursued by the British was an appeal for the United States to base capital ships of the Pacific Fleet in Singapore—a request that was ultimately refused.

Start of the Invasion of Invasion of Malaya on December 8, 1941

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “The invasion fleet left the port of Samah on 4 Dec 1941. Although detected by British scout planes two days earlier, bad weather provided stealth for the invasion convoy. On 8 Dec, after some fighting at Kota Bharu, the Japanese troops took coast cities of Singora (Thailand), Patani (Thailand), and Kota Bharu (Malaya). British planes attempted to attack landing ships, but Japanese troops made beachhead at Kota Bharu within three hours despite the air distraction. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com ]

“At an airfield near Kota Bharu, Indian troops who received incorrect intelligence that the Japanese were far ahead than where they actually were killed their own commander Lt. Col. Hendricks and fled the airfield without destroying anything, providing the Japanese invaders a fully working airfield along with fuel and ammunition. General Yamashita, in Singora, negotiated with the Thai government, and won an agreement that allowed Japanese troops to move within Thai borders toward Malaya without local resistance.

“Meanwhile, Colonel Tsuji's men, disguised in civilian attire, secured key bridges beyond Malaya's borders before the British could destroy them on their retreat. No reinforcements from United States' Philippines appeared during the landings, as the US forces were busy fending off a nearly simultaneous invasion at Philippines and at Pearl Harbor. On the same day, 8 Dec, Japan sent her first air raid on the city of Singapore, resulting in 61 deaths. British command in Singapore still did not call for a general blackout of the city.”

Battle off Kuantan on December 10, 1941

With Germany threatening Europe, most of the Royal Navy was recalled to defend home waters and the Mediterranean, leaving Britain’s Pacific interests to a small force of capital ships. This included the battlecruiser Repulse, armed with six 15-inch guns under Captain W. G. Tennant; the newly commissioned battleship Prince of Wales, carrying ten modern 14-inch guns and commanded by Captain J. C. Leach; and the aircraft carrier Indomitable, a 23,000-ton ship with 45 aircraft. This group, known as Force G, was sent toward Singapore. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com ]

The Indomitable ran aground off Jamaica on 3 November 1941 and was forced to undergo repairs in the United States, missing the coming battle but surviving the war. Repulse and Prince of Wales rendezvoused near Ceylon, were redesignated Force Z, and reached Singapore just as news arrived of Japan’s attacks across the Pacific. Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, aboard Prince of Wales, decided to sail up the Malayan coast to disrupt Japanese landings.

After turning toward Kuantan on reports of a Japanese landing, Force Z was spotted by submarine I-58, which alerted Japanese air units. On 10 December, Japanese reconnaissance aircraft located the British ships, and air attacks followed. Lacking air cover, the two capital ships were repeatedly struck: Repulse sank at 12:33 p.m., and Prince of Wales was abandoned shortly after, with the loss of Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach.

The battle, in which Japan lost only three aircraft, underscored the decisive role of air power in naval warfare. Ironically, just 11 days later Japan launched the giant battleship Yamato, even as the era of big-gun dominance was already fading.

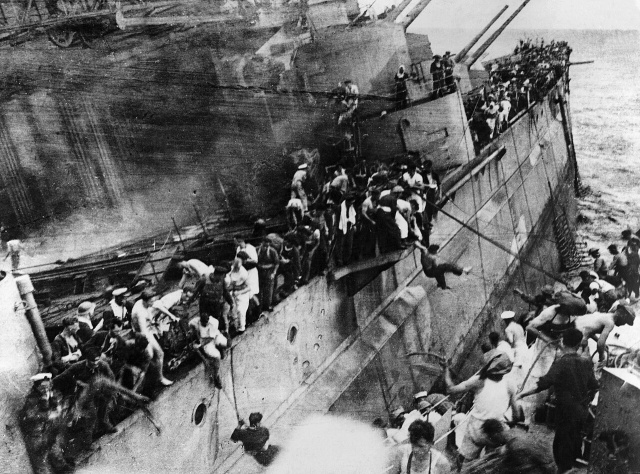

Sinking of the Repulse

On December 10, 1941, three days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese planes and submarines sunk the British warships, “The Prince of Wales”, nicknamed HMS “Unsinkable”, and the “Repulse”. Both ships lacked air cover. "In all the war,” Churchill later wrote. "I never received a more direct shock."

Describing the attack from the deck of the Repulse”, British journalist Cecil Brown reported: "The torpedo strikes the ship about twenty yards astern of my position. It feels as though the ship has crashed into dock. I am thrown four feet across the deck but I keep my feet. Almost immediately, it seems, the ship lists...Instantly there's another crash to starboard. Incredible quickly, the “Repulse” is listing to port...Captain Tennant's voice is coming over the ship's loudspeaker, a cool voice: 'All hands on deck. Prepare to abandon ship.' There is pause for just an instant, then: 'God be with you." There is no alarm, no confusion, no panic. We on the flag deck move towards the companionway leading to the quarterdeck...There is no pushing, but no pausing either." [Source: “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey, Avon Books, 1987]

"Men are tossing overboard rafts, lifebelts, benches pieces of wood, anything that will float. Standing on the edge of ship I see one man" dive "170 feet and starts to swim a way...Men are jumping into the sea from the four or five defense control towers that segment the main mast like a series of ledges. One misses his distance, dives, hits the side of the “Repulse”, breaks every bone in his body and crumples into the sea like a sack of wet cement. Another misses his direction and dives from one of the towers straight down the smokestack."

"Men are running along the deck of the ship to get further astern. The ship is lower in the water at the stern and their jump therefore will be shorter. Twelve Royal Marines run back to far, jump into the water and are sucked into the propeller. The screws of the “Repulse” are still turning. There are five or six hundred head bobbing in the water. The men are still being swept astern because the “Repulse” is still making way and there's a strong tide here, too...I see one man jump and land directly on another man. I say to myself, 'When I jump I don’t want to hurt anyone.' Down below is a mess of oil and debris. I don't wan to jump into that either...The jump is about 20 feet. The water is warm; it is not water but thick oil.”

"About eight feet to my left there’s a gaping hole in the side of the “Repulse”. It is about 30 feet across, with the plates twisted and torn. The hull of he “Repulse” has been ripped open as though a giant had torn open a tin can. Fifty feet from the ship, hardly swimming at all now, I see the bow of the Repulse” swing straight into the air like a church steeple. Its red underplates stand out stark and as gruesome as the blood on the faces of the men around me. Then the tug and draw of the suction of 32,000 tons of steel sliding to the bottom hits me."

"Something powerful, almost irresistible, snaps at my feet. It feels as though someone were trying to topple my legs out by the hip sockets. But I am more fortunate than some others. They are closer to the ship. They are sucked back. When the Repulse” goes down it sends over a huge wave, a wave of oil. I happen to have my mouth open and I tale aboard considerable oil. That makes me terribly sick at the stomach."

Fall of Jitra and Penang in Mid-December, 1941

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “The 11th Indian Division was in no shape to defend Jitra with no working communications systems and flooded trenches. The oncoming Japanese attack captured several artillery and anti-aircraft guns, however, the attack on the city of Jitra on the night of 11 Dec caused heavy losses among the Japanese troops. A shift in tactics allowed the Japanese column to drive a deep wedge into the center of the British line of defense, and then the addition of a reinforcement force broke through the line. During the British retreat, there was much confusion due to the lack of a good communications system, and it was fueled by unorthodox tactics employed by the Japanese, including snipers under disguise as local civilians. The Japanese forces would push to the vicinity of Penang within days. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com ]

“Penang was an island garrison, consisted of four anti-aircraft guns and 500 troops. The first attack on the island by the Japanese was as early as 11 Dec, in the form of air raids. During one of the raids, a bomb was dropped on a firestation, which resulted in no firefighting capability from the civilians. Some RAF resistance was present, but was largely unsuccesful. The city fell under a state of lawlessness within days, with uncontrollable looting while corpses were left rotting on the streets.”

On December 17, “Japanese troops landed on the island of Penang with no resistance, as British forces had already evacuated the island on the previous day. Once again, the British failed to destroy resources that could be used by the invaders, including a fully functional radio station. The Japanese troops used the radio station to broadcast the cruel message "Hello, Singapore, this is Penang calling. How do you like our bombing?" and proceeded to massacre the Penang residents during a large-scale looting. General Tamashita called a stop to the atrocities, and executed three soldiers as punishment. Lt. Col. Kobayashi was also placed under arrest as punishment. However, the image of the Japanese as brutal conquerers would forever be carved in the minds of the natives.

“General Archibald Wavell, British commander-in-chief in the area, had little confidence in Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, who was in tactical command of the defending troops. During the defensive campaign, Wavell interfered in Percival's decision making on several occasions, but he repeated failed to replace Percival, thus further weakening the British ability to fight.”

Fall of Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942

By 11 January, Japanese tanks had reached the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur and captured the capital with relatively little resistance. There, General Yamashita seized large stocks of food, fuel, and ammunition, easing the severe supply problems caused by his long lines of communication from Siam and northern Malaya. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, ww2db.com]

Within weeks, British forces were steadily pushed back toward Singapore as Japanese units pressed south. Gordon Bennett and his Australian 8th Division mounted a series of ambushes that inflicted casualties but failed to significantly slow the advance. Demolished bridges delayed Japanese momentum, yet they still reached Gemas by 15 January and Johore by the end of the month. Singapore’s fortress loomed ahead, with British losses—killed, wounded, or captured—equivalent to two divisions, while Yamashita’s forces had lost about 5,000 men, including roughly 2,000 killed.

Describing the fall of Kuala Lumpur on January 11, 1942, Ian Morrison wrote: "Civilian authority has broken down. The European officials and residents had all evacuated. The white police officers had gone and most of the Indian and Malay constables had returned to their homes in the surrounding villages...There was looting in progress such as I have never seen before. Most of the big foreign department stores had already been whistle clean since the white personal had gone. There was now a general sack of all shops and premises going on...Looters could be seen carrying every imaginable prize way with them. Here was one man with a Singer sewing-machine over his shoulder, there a Chinese with a long roll of linoleum tied to the back of his bicycle, here two Tamils with a great sack of rice suspended from a pole." On January 27 the defense of Malaysia was abandoned.

Image Sources: YouTube, National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons; Gensuikan;

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026