SEROWS

Serows look like a cross between a goat and an antelope. Weighing between 25 and 80 kilograms as adults, they are about a meter in length, stand 70 to 85 centimeters at the shoulder, and have dagger-like horns, mule-like ears, brown, gray, black or white fur and acute vision, hearing and smell. Both males and females have horns. The horns are not shed annually like deer antlers; they are kept all year round. At the base of the horns and under their eyes are special glands that produce sweet-sour-smelling secretions that the animals use to mark their territory.

Serow are one of the most primitive members of the goat-antelope family. Fossils of an animal remarkably similar to a serow have been found in 35 million year old rocks. The maximum lifespan observed in a serow is 20 to 21 years for males and 21 to 22 years for females in Japanese serow. At birth, females have shorter life expectancies, 4.8 to 5.1 years, compared to males, with life expectancies of 5.3 to 5.5 years. /=\

Serow inhabit forests and scrublands, including tropical and montane environments and feed on grass, shoots and leaves. In Japan serow inhabit steep slopes of mountains forested with beech and oak. They are sure-footed on mountain slopes and comfortable in dense vegetation. Using their lips and tongues to gather food, they are ruminants and browsers that fed on tree leaves, fruits, flowers, buds, acorns and nuts. They like to eat cedar saplings and thrive in artificial forests.

Serow,s are even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyls) and bovids (see Below) related to mountain goats, musk ox and chamois. In addition to the Japanese serow described below, there is a slightly related but different species of serow in Taiwan. They are also closely related to another species that ranges across the Asian mainland from Sumatra to the Himalayas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEROWS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, HABITAT factsanddetails.com

ANIMALS IN JAPAN: WILDLIFE, BIODIVERSITY, RESEARCH factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS AND JAPAN: MAMMALS, BIRDS, SPECIES, PROTECTION, ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE factsanddetails.com

EXTINCT ANIMALS IN JAPAN: WOLVES, BIRDS AND OTTERS factsanddetails.com

TANUKIS (JAPANESE RACCOON DOGS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

IRIOMOTE CATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

SMALL MAMMALS IN JAPAN: SABLES, CUTE STOATS, MARTENS, SHREW MOLES factsanddetails.com

ITACHI (JAPANESE WEASEL): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

FLYING SQUIRRELS IN JAPAN: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BEARS IN JAPAN: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Serow Animal Picture Archives animalpicturesarchive ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

Japanese Serow

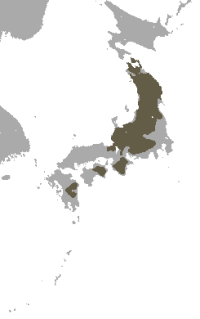

Japanese serows (Capricornis crispus) are known as “kamoshika” in Japanese They are endemic to Japan and inhabit areas with temperate climate similar to that of the U.S. and Europe. They live in dense woodland in the mountains of Kyushu, Honshu and Shikoku, primarily in northern and central Honshu Japanese serow prefers temperate deciduous forest, but also lives in broad-leaved or subalpine coniferous forest made up of Japanese beech, Japanese oak, alpine meadow, and coniferous plantations. Population densities are low, at an average of 2.6 per square kilomete (6.7 per square mile), peaking at around 20 per square kilometer (52 per square mile) They have disappeared from the Chugoku region and their numbers are shrinking in Shikoku and Kyushu. In many places though protection has helped their numbers increase. Scientifically Japanese serows are recognized as Capricornis crispus,. In the past they were known by the name Naemorhedus crispus.

Japanese serows are primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), and are also classified as folivores (eat leaves). They are browsers and foragers and ruminants with a four-chambered stomach. They primarily on the buds and leaves of deciduous broad-leaved trees, coniferous leaves, plant shoots and fallen acorns. They sometimes eat flowers, fruits, wood, bark, stems, seeds, grains and nuts. Japanese serow tend to eat grass and fresh leaves in the spring and consume the leaves of young fir and hemlock saplings in the winter. Japanese serows feeds on alder, sedge, Japanese witch-hazel (Hamamelis japonica), and Japanese cedar and adjust their diet to what food is locally available. Studies indicate that even severe winters have a negligible impact on the serow's food intake. This may be because they select a territory with sufficient food supply. Defecation occurs in specific locations.

Japanese serows have no real predators other than humans and dogs. They may have once been hunted by Japanese wolves but these wolves have been extinct since the early 1900s. The serow’s range overlaps with that of Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus). However, Asiatic black bears are not highly predatory and serow can easily outrun them. [Source: Kensuke Mori, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Japanese serows have a maximum lifespan of 20 to 21 years for males and 21 to 22 years for females. Life expectancies at birth are 5.3 to 5.5 years for males and 4.8 and 5.1 years for females. One study found that serows live in same territory for 11.7 to 12.4 years. Serows disperse from their natal territories at age two to four years to establish their own territories. This means they live most of their lives in a territory they established.

Bovids

Serows are bovids. Bovids (Bovidae) are the largest of 10 extant families within Artiodactyla, consisting of more than 140 extant and 300 extinct species. According to Animal Diversity Web: Designation of subfamilies within Bovidae has been controversial and many experts disagree about whether Bovidae is monophyletic (group of organisms that evolved from a single common ancestor) or not. [Source: Whitney Gomez; Tamatha A. Patterson; Jonathon Swinton; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Wild bovids can be found throughout Africa, much of Europe, Asia, and North America and characteristically inhabit grasslands. Their dentition, unguligrade limb morphology, and gastrointestinal specialization likely evolved as a result of their grazing lifestyle. All bovids have four-chambered, ruminating stomachs and at least one pair of horns, which are generally present on both sexes.

Bovid lifespans are highly variable. Some domesticated species have an average lifespan of 10 years with males living up to 28 years and females living up to 22 years. For example, domesticated goats can live up to 17 years but have an average lifespan of 12 years. Most wild bovids live between 10 and 15 years, with larger species tending to live longer. For instance, American bison can live for up to 25 years and gaur up to 30 years. In polygynous species, males often have a shorter lifespan than females. This is likely due to male-male competition and the solitary nature of sexually-dimorphic males resulting in increased vulnerability to predation. /=\

See Separate Article: BOVIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBFAMILIES factsanddetails.com

Japanese Serow Characteristics

Japanese serow range in weight from 30 to 45 kilograms (66 to 99 pounds), with their average weight being 37 kilograms (81.50 pounds). Their average body length is 1.3 meters (4.26 feet). They stand 65 centimeters (2.13 feet) at the shoulder. They are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them), warm-blooded (homoiothermic, have a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. They both have horns and are difficult to distinguish by sight. Researchers use genitalia and sexual behaviour to distinguish the sexes. Females have two pairs of mammae. [Source: Wikipedia, Kensuke Mori, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Japanese serows have a stocky body and are similar in appearance to goats. Their short, backwards-curving horns average 12 to 16 centimeters (4.7 to 6.3 inches) in length. Their bushy tail is 6 to 6.5 centimeters (2.4–2.6 inches) long.Japanese serow are small bovids, whose morphology is primitive compared to other bovids. Their hooves are cloven. Compared to mainland serow, the ears are shorter and the coat is typically longer and woollier—about 10 centimetres (3.9 inches) on the body. There are three well-developed skin glands: The large infraorbital glands below the eye sockets are found in both sexes and used in scent marking their territories. These gland are easily seen and increase in size as the serows ages. There are also preputial glands and poorly developed interdigital glands in all four legs.

The fur of Japanese serows is black to whitish, but generally gray, and lightens in summer and in the northern part of their range. The fur is very bushy, especially the tail. The is whitish around the neck. Fur on the body may be black, black with a dorsal white spot, dark brown, or whitish. The adult's 32 permanent teeth form by 30 months, and have a dental formula of 0.0.3.3 3.1.3.3 The inner sides of the teeth become blackened with a hard-to-remove substance, likely tree resin. The tongue has a V-shaped apex.

The horns of Japanese serow begin to develop at about four months and continue to grow throughout their lives. The sheaths of the horns have a series of transverse rings. Environment affects the size of the first growth ring. Size, curvature, and thickness and number of transverse rings are indicative of age. Up to two years, there are thicker transverse rings, of greater length and flexion than in adults. Into adulthood, thinner horn rings force the thick transverse rings upward. Growth increment slows earlier in maturation in females than in males.

Japanese Serow Behavior and Communication

Japanese serows spend much of their time in open grasslands and forests at elevation of around 1,000 meters (3,300 feet). They use caves to rest in and are known to stand on high lookouts for extended periods of time. This behavior could be to detect predators or territorial rivals. These serows stomp their hooves as a warning to others if they pick up a scent they don’t like such as of hunting dogs. When they flee they do so with a whistling snort. They are very agile, sure-footed mountain dwellers that are able to sprint up mountains and to jump from cliff to cliff to safety. They can escape by fleeing on sheer rock faces that would send lesser animals to their death. Hunters likened their displays of agility to that of ninja. [Source: Wikipedia]

Japanese serows are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range). Their average territory size is 105-166 square kilometers. [Source: Kensuke Mori, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Japanese serows are mostly solitary animals, but sometimes are found in pairs, or in small family groups and form intrasexual territories. Males and females establish separate, overlapping ranges, typically 10–15 hectares (25–37 acres), but the males’ are typically larger than females’. They mark their territories with the scent gland located in front of the eyes. Aggression is rare but serow sometimes react with hostility to territorial incursions. Encounters between adults serows of same sex can result in aggression, in which intruders are chased out of the territories. Deaths from combat injury occur among males in some cases. Territory size is affected by the food availability. Japanese serows were considered diurnal, but a study using radio collared individuals found that they are almost as active during night.

Japanese serow sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. They have acute hearing and strong eyesight and are able to detect and react to movement from a distance, and in low lighting. Serows also have a good sense of smell; they are often observed raising their head and sniffing the air around. Japanese serows use scent marking to define territories and stake their claim to them. Aslo, the are generally solitary animals, with few encounter of other members of their species, and thus use scent marking as their primary method of communication. Females use sound to call their young.

Japanese Serow Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Japanese serows are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding: once a year, usually between September to November. During a courtship ritual that resembles that of goats or gazelles, a male licks the female's mouth, strikes her on the hindlegs with his forelegs, and rubs her genitalia with his horns. Both sexes display Flehmen responses. The number of offspring ranges from one to three, with the average number of offspring being one. The gestation period ranges from 210 to 220 days. . The average weaning age is five months and the average time to independence is one year. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 2.5 to three years. [Source: Wikipedia, Kensuke Mori, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Japanese serows usually form monogamous pairs. However, some males mate with two and occasionally three females in the same breeding season. According to Animal Diversity Web: Two field studies at different locations found a similar proportion of polygynous males (20-30 percent), suggesting that the proportion of animals that mate polygynously is perhaps fixed in the species. Both sexes form territories that they defend against other individuals of the same sex. Usually male territories almost completely overlap those of a female, but sometimes male territories include territories of more than one female. In these cases, those males are polygynous. Mated pairs remain together every year, perhaps because they hold consistent territories. When a mate is displaced from their territory, their mate remains in the same territory and mates with the individual that takes over the territory of the displaced animal. /=\

Japanese serow are altricial. This means that young are born relatively underdeveloped and are unable to feed or care for themselves or move independently for a period of time after birth. Most of the parenting is done by females. Males provide no parental care to the young, although they permit young within their territories. The young are born in May to August. The birth takes about half an hour, and the female walks about during it. Fawns are 30 centimeters (one foot) tall. Lactation continues until winter. Young remain with their mother for about a year at which time they reach adult height. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Although serows become independent at about a year old, they remain in their natal territory. They disperse between two to four years of age, but females may inherit their mothers' territories.

Japanese Serows and Humans

Serows are viewed as a national symbol of Japan. In the 1970s, when the Chinese government gifted Japan a giant panda, the Japanese government gave the Chinese two Japanese serow in return. Historically, serows have been given a variety of names, often based their appearance, which translate as "mountain sheep", "wool deer", "nine tail cow", and "cow demon". There are numerous regional names, some of which translate as "dancing beast", "foolish beast", or "idiot". Japanese people often characterized serow as "strange" or "abnormal", and they were seen as "phantom animals" as they tended to live alone in the depths of remote forests, and looked down on people from places high in the mountains. [Source: Wikipedia]

Until the mid-20th century, serow meat was so widely eaten in parts of central and northern Japan that these animals themselves were known as "meat". Their waterproof hides were used for rafters' backflaps, their horns were ground into medicines used as preventives against diseases such as beriberi. A cure for stomach-aches was made from the serow's small intestines and gall bladder.

Serow have traditionally been hunted with dogs who corner them so hunters can shoot them. Serow have a bad habit of looking back at their pursuers, which gives them time to catch up, rather than just making a run for it. In May 2005, a 74-year-old woman in Yamagata was injured after being attacked by a serow that escaped from a pet house at a primary school. The three-year-old serow hit the woman with its horns.

Japanese Serow Conservation

Serow are elusive but not endangered. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Humans have hunted serows for meat and hide in the past. They are currently protected as a Japanese natural heritage and hunting is prohibited. Recently, dog predation has been found to be a leading cause of death to serows in some areas. [Source: Kensuke Mori, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Japanese serows have been designated as protected species and special natural monument by the Japanese government. They were hunted to near extinction by people in the past but now are found in relatively healthy numbers in many places. Their main threats are habitat loss and degradation but there are a lot of forests in Japan, may with few humans nearby, where they can live. Because they browse on trees, they are sometimes regarded as pests by forestry officials as they damage planted trees. They have been killed in the name of forest management to control damage to forestry plantations. They are also regarded as crop pests in some places.

Japanese serow came close to becoming extinct. In western Honshu, Japanese serow had become extinct by the 20th century. Elsewhere, it had been hunted to such a severe degree that the Japanese government declared it a "Non-Game Species" in a 1925 hunting law. In 1934, the Law for Protection of Cultural Properties designated it a "Natural Monument Species".

Poaching continued, leading the government to declare the Japanese serow a "Special Natural Monument" in 1955, at which point overhunting had brought its numbers to 2000–3000. [Source: Wikipedia]

Serows Make Miraculous Recovery

Populations of Japanese serow in the 1950s and 60s as police put an end to poaching, and post-War monoculture conifer plantations created favourable environments for the animal. By the 1980s, population estimates had grown to up to 100,000 and serow range had reached 40,000 square kilometres (15,000 square miles). Between 1978 and 2003, its distribution increased 170 percent, and their population had stabilized. [Source: Wikipedia]

In September 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The Japanese serow, an animal once considered nearly extinct, has made what one expert calls a miraculous recovery. In Ishikawa Prefecture, the serow's habitat is said to have expanded five times from what it was half a century ago, and one of the animals was seen recently in Kanazawa's Chaya district, famous for its geiko community. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 27, 2012]

The expert said it was extremely rare in the world for a once-endangered animal to restore its population in about 50 years. Although the government banned serow hunting in 1925, poachers continued to hunt them until the 1950s as their meat was a source of protein and the fur and antlers a source of income. The serow took to steep mountainous areas to survive.Full-fledged conservation activities started in 1955 and a nationwide crackdown on poaching was launched in 1959. Thanks to these efforts, the area inhabited by the serow doubled by 2003 compared to surveys carried out from 1945 to 1955, the Environment Ministry said.

The ministry also said the population has grown remarkably in the Hokuriku, Chubu and Tohoku regions. Akinori Mizuno, director of the Ishikawa Museum of Natural History, said Japanese serows in Ishikawa Prefecture used to live only in a 300-square-kilometer area around Mt. Haku in 1955. By 2005, the animals had expanded their habitat to a 1,500-square-kilometer area, he said.

They have recently been spotted in satoyama--areas between mountain foothills and arable flat land--close to an urban area of Kanazawa. In May, a Japanese serow was spotted in a parking lot in a Kanazawa sightseeing area, where it made a great effort to escape before being captured by city officials and police officers.

In Kyushu, especially in the mountain range covering part of Kumamoto, Miyazaki and Oita prefectures, the number of Japanese serows are decreasing because of a food shortage, as they have to compete with a sharp increase in Japanese deer, which have a similar diet and stronger reproductive rates.

According to surveys by the three prefectural boards of education, the number of Japanese serows living in the prefectures in fiscal 2003 totaled about 650, a sharp drop from 2,200 in fiscal 1995. The Environment Ministry's red list still designates the Japanese serow in the Kyushu region as endangered. An official of the Oita prefectural board of education said, "We will take conservation measures after studying the actual living conditions of [the animals] and the causes of depopulation.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025