ANIMALS IN JAPAN

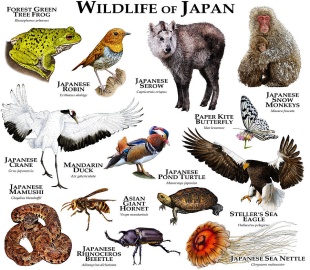

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Japan has over 90,000 native species, most of them insects. Over 4,900 species, with all or part of their range in Japan have been assessed for The IUCN Red List – around 80 percent of which exist in aquatic systems. Iconic examples include the Brown Bear (Ursus arctos), the Japanese Macaque (Macaca fuscata), the Japanese Raccoon Dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides), the Large Japanese Field Mouse (Apodemus speciosus), and the Japanese Giant Salamander (Andrias japonicus).

A total of 172 species of mammals — including 112 native terrestrial mammals, 19 introduced species, and 40 species of Cetacea (whales and dolphins) — have been identified in Japan. Of the species of land mammals, not including foreign species and livestock, only 15 species are large mammals, such as wild boars, bears and deer. Among the more interesting mammals are ermines, foxes, flying foxes, Iriomote cats and seals. There are over 250 bird species that breed in Japan and dozens of reptiles and amphibians. Japan’s waters team with aquatic life. Great migrations of fish drift in with the Tsushima and Kuril Currents. There are large numbers and varieties of insects. Those such as stink bugs and hornets, which are regarded as invasive pests outside of Japan are not as destructive at home because there are natural predators that keep their numbers in check. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Japan has a temperate climate like the U.S. and Europe. Some mammals in Japan like bears hibernate in the winter; others like squirrels, ermine, weasels, foxes and hares do not. Acorns are a primary source of food for a wide variety of animals: bears, deer, snow monkeys, wild boars, squirrels as well as a variety of birds. Acorns are critical for providing both hibernating and non-hibernating mammals with nourishment to give them layers of fat they need to get through the winter. Many animals suffer in years when acorn production is low. Bears and wild boar attacks often increase those years.

Through the Edo period (1603-1868) the hunting of animals and birds was strictly controlled and wild animals prospered. During the Meiji period, beginning in 1868, the controls were lifted and wild animals suffered. Some became extinct. These days Japan seems to be making up for years of environmental neglect with a newfound concerns for nature and animals.

Japan is a leader in animal and wildlife research. Many Japanese names and universities appear on papers and studies that cover a wide range of land animals and sea life. Land crabs are fairly common on Kyushu and Honshu. They live in pools of water that collect in leaves. In Kyushu there are 25-centimeter (10-inch) -long blue earthworms.

Animals in Japan: Animal Info animalinfo.org/country/japan Endangered Animals in Japan: Animal Info animalinfo.org/country/japan ; List of Extinct Animals env.go.jp/en/nature

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAPANESE HABITATS: FORESTS, SATOYAMA AND RICE PADDY ECOSYSTEMS factsanddetails.com

DINOSAURS AND PREHISTORIC ANIMALS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS AND JAPAN: MAMMALS, BIRDS, SPECIES, PROTECTION, ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE factsanddetails.com

EXTINCT ANIMALS IN JAPAN: WOLVES, BIRDS AND OTTERS factsanddetails.com

ALIEN SPECIES IN JAPAN: FISH, TURTLES, MONGOOSES, RACCOONS, NUTRIA factsanddetails.com

TANUKIS (JAPANESE RACCOON DOGS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

BEARS IN JAPAN: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Japan: a Biodiversity Hotspot

The entire archipelago of Japan was declared a Biodiversity Hot Spot in 2005 because it is rich in unique animal and plant life and because this unique animal and plant life is threatened by the encroachment of people. Japan’s great biodiversity can be attributed to: 1) the fact that Japan is comprised of many islands, which often have their own unique self-contained ecosystems; 2) the islands stretch over a wide variety of climates, with different species often living in each climate zone; and 3) Japan’s links to the Asia and the mainland were via three diverse regions: a) Siberia, b) Korea and China, and c) a chain of islands that leads to Taiwan and Southeast Asia.

The islands that make up the Japanese Archipelago stretch from the humid subtropics in the south to the boreal zone in the north, resulting in a wide variety of climates and ecosystems. About a quarter of the vertebrate species occurring in this hotspot are endemic, including the Critically Endangered Okinawa woodpecker and the Japanese macaque, the famous “snow monkeys” that are the most northerly-living non-human primates in the world. Japan has a relatively high diversity of amphibians as well, with 75 percent being endemic to the islands. Urban development has had some of the most significant effects on the Japanese wilderness, as are introduced exotic species like the Indian grey mongoose, the Siberian weasel, and the large mouthed bass. [Source: Conservation International Biodiversity Hotspot]

VITAL SIGNS: 1) Hotspot Original Extent (km²): 373,490; 2) Hotspot Vegetation Remaining (km²): 74,698; 3) Endemic Plant Species: 1,950; 4) Endemic Threatened Birds: 10; 5) Endemic Threatened Mammals: 21; 6) Endemic Threatened Amphibians: 19; 7) Extinct Species: 7; 8) Human Population Density (people/km²): 336; 9) Area Protected (km²): 62,025; 10) Area Protected (km²) in Categories I-IV*: 21,918. “Recorded extinctions since 1500. *Categories I-IV afford higher levels of protection.

Encompassing more than 3,000 islands of the Japanese Archipelago, this hotspot includes the land area of the nation of Japan (roughly 370,000 km²). In addition to the four main islands — Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu — Japan includes a number of smaller island groups, including the Ogasawara-shoto (the Bonin Islands and Iwo or Volcano Islands), Daito-shoto, Nansei-shoto (Ryukyu and Satsun Islands) and the Izu-shoto. Japan is located at the intersection of three of the Earth’s tectonic plates, and the slippage of these plates generates forces that result in numerous volcanoes, hot springs, mountains and earthquakes.

Japan stretches from around 22̊N to about 46̊N latitude, from the humid subtropics in the south to a temperate zone in the north. This latitudinal range, and the country’s mountainous terrain (about 73 percent of Japan is mountainous, the highest point being the 3,776-meter Mt. Fujiyama) contribute to Japan’s widely varying climate. While the central mountain area of Honshu is one of the snowiest regions on Earth, the Pacific side of Japan is remarkably dry. Yaku-shima, just south of the southern tip of Kyushu, is one of the wettest places on Earth, with annual rainfall of over 5,000 millimeters in some places.

Japan’s vegetation ranges from boreal mixed forests of Abies (fir), Picea (spruce) and Pinus (pines) on Hokkaido (and at high elevations in Honshu and Shikoku) to subtropical broadleaf evergreen forests and mangrove swamps in the south. High elevations on Honshu and Shikoku support alpine vegetation, while subalpine vegetation and natural beech forests are distributed throughout the region. The subtropical island chains in the south of Japan support a flora and fauna different from that of the main islands and hold many endemic species.

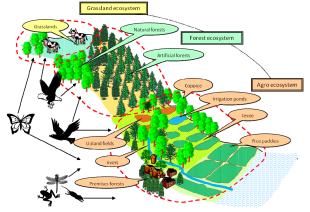

Animal Habitats and Rice Paddies in Japan

Hokkaido wilderness Most native animal species such as bears, wild boars, tanukis, and badgers are adapted for life in the forest. These days you see very few wild animals in Japan. The forests are almost devoid of life.

Man-made environments are sometimes almost as rich in wildlife as natural ones. Japan’s rice paddies have their own ecosystems. Dragon flies and frogs , for example, thrive in the paddies and irrigation ditches and provide food for large animals such as birds and fish.

Many animals in Japan have adapted to paddy agriculture. Among the forms of wildlife that thrived in rice paddies until chemical pesticides and fertilizers became widely used were egrets, herons, cranes, storks, ibises, frogs, snakes, fish, snails, clams. dragonflies, aquatic insects, insect larvae, shrimp, crabs and shrimp. Many spend the winter resting in paddy mud and come to life in the spring. Frog sounds are common by April, Among the birds are egrets and herons, whose long legs are well suited for hunting in the sallow water

The modernization of rice paddy agriculture has made the paddies less accommodating to animals. Things like the replacement of open canals with underground drainage pipes and periodic draining of the paddies have made the paddies easier for farmers to work but have taken away the water that the animals need to live.

See Separate Article: JAPANESE HABITATS: FORESTS AND RICE PADDY ECOSYSTEMS factsanddetails.com

Animals and Japanese Culture

Animal figures are important in the culture of Japan. Chinese classical literature is the source of many of the beliefs embraced by the Japanese about various animals. In the protohistoric and ancient periods, the Japanese elite adopted from the Chinese such traditional animal symbols as cranes and turtles (for happiness and longevity) and swallows (for a faithful return). Certain animals have special places in the folklore of Japan. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The “tanuki “(racoon dog), often seen near villages, has traditionally been thought of as a weird creature with supernatural powers. In old tales it often bewitches people, although its tricks are more frightening than harmful. In fact, it is usually depicted in figurines as a rather comical animal with a big belly and huge testicles, carrying a “sake “bottle.

“The fox has also been considered an animal with supernatural powers, and a messenger of Inari Myojin, the deity of agriculture. Foxes are thought to be clever and tricky. In the olden days they were said to cast a spell on people traveling at night. Sometimes, it was said, foxes would even possess people and make them insane. Belief in Inari still exists today, and the fox is worshipped at Inari shrines throughout the country.

“Buddhist teachings have influenced people’s attitudes toward animals. Until late in the nineteenth century, for example, almost no Japanese would slaughter a four-legged animal, relying instead on fish for their animal protein.

“Then there is the sexagenary cycle of the ancient Chinese calendrical system, in which one animal (rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog, and boar) represents each subcycle of 12 years. The year 2010 is the year of the tiger, and the next year, the rabbit. Even in today’s Japan, virtually everyone associates his or her birth year with a particular animal’saying, for example, “I was born in the year of the horse” — and it is assumed that one’s character and fortune in life are influenced by the animal representative of their birth year.

Animal Diversity in Japan

Many species and relicts not found in neighboring countries are included in Japan’s fauna. Just as its plant life is greatly diversified thanks to widely differing climatic conditions from north to south, so are the Japanese islands inhabited by animals from contrasting climates: Southeast Asiatic tropical animals, temperate-zone Korean and Chinese animals, and Siberian subarctic animals. Brightly colored tropical coral fish, turtles, and sea snakes flourish in the tropical sea of the Ryukyu Islands, which is also home to the dugong and the black finless porpoise. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

In the sea to the north of central Honshu we find sea lions, fur seals, and beaked whales. Arctic region animals such as the walrus sometimes visit Hokkaido, the northeastern side of which faces the Sea of Okhotsk. On land in Japan’s southern extremity, the Ryukyu Islands are inhabited mostly by tropical animals such as the crested serpent eagle, the flying fox, and the variable lizard. On the mainland islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu wander “tanuki “(racoon dogs), “sika “deer, and mandarin ducks, which are from the deciduous forests of Korea as well as central and northern China. From the Siberian coniferous forests come the brown bear, hazel grouse, and common lizard. The distribution of animals tends not to be continuous because historically the Japanese islands have repeatedly separated from and rejoined the Asian continent, resulting in animal migration that is extremely complex. Furthermore, the animals found in a particular part of Japan are not always the same as those found in corresponding areas of the continent; many are found only in Japan.

Among the species that are endemic to the Japanese mainland are the Japanese dormouse, the Japanese macaque, the copper pheasant, the Japanese giant salamander, and the primitive dragonfly. Likewise, in the Ryukyu Islands, which scholars believe became separated from the continent much earlier than the mainland did, live Pryer’s woodpecker and the Amami spiny mouse. The Shimokita Peninsula, at the northern end of Honshu, is the northernmost habitat in the world of any simian.

In the depth of the sea, such living fossils as the horseshoe crab, the slit shell, and the frilled shark can be found. Still other Japanese aquatic animals are the giant spider crab (the largest crustacean in the world) and the freshwater Japanese giant salamander (the largest amphibian on earth, also said to live almost 50 years).

Asian land salamanders, cicadas, and dragonflies inhabit the islands in many forms. There are eight species of swallowtail butterflies on the mainland alone. Many animals in Japan, however, are facing extinction. For example, the Japanese crested ibis (“Nipponia Nippon”) became extinct in 1997. The endangered species include the Iriomote cat (“Mayailurus iriomotensis”), Japanese otter (“Lutra nippon”), albatross (“Diomedea albatrus”), and stork (“Ciconia ciconia boyciana”).

Many Animals in Japan Sighted Less Than Before

In 2017, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: Animals and plants subject to phenological observation — the tracking of seasonal natural phenomena — by the Japan Meteorological Agency are being spotted less often due to advancing urbanization. Barn swallows, for example, have gone unobserved the last two years in central Tokyo, and some animals have even been removed from the list of observed species due to a lack of sightings. “These days, we have a hard time finding the animals we’ve been observing unless we look more carefully than before,” said an official at the Tokyo Regional Headquarters responsible for observations in central Tokyo. [Source: The Yomiuri Shimbun, March 18, 2017

“The observations are carried out by 58 regional headquarters or weather stations across the nation. Officials search within a five-kilometer radius from their headquarters or stations and record the date they first observe a subject animal, hear a subject bird sing or observe a subject flower begin to bloom. The meteorological agency has compiled data obtained throughout the nation since 1953, including on flowering cherry trees. The Tokyo Regional Headquarters handles animal and plant observations in the Otemachi area and Kitanomaru Park near the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo.

“Barn swallows, once observed around April each year, have not been spotted since 2015, while the Japanese bush warbler, dubbed “harutsugedori” or bird that heralds the coming of spring, was last confirmed by a headquarters official in 2000. The high-pitched buzzing of the evening cicada has not been heard since 2002.

“While the meteorological agency lists 23 animals and plants as under phenological observation, some have been removed as targets in certain areas due to a rule that stipulates removing species that fail to meet such conditions as having been spotted “at least eight times in 30 years.” In accordance with the rule, the Tokyo headquarters in 2011 removed six target species including the small white butterfly and skylark, leaving it to focus on five species: large brown cicada, Japanese bush warbler, common skimmer, barn swallow and evening cicada. “Stain-resistant materials used for buildings and the lack of soil [in urban areas] seem to have created an environment unsuitable for living things to grow,” said the Tokyo headquarters official.

“As a matter of fact, similar phenomena have occurred in provincial cities. The Mito Meteorological Office in Mito has been unable to confirm the existence of black-spotted pond frogs since the last time they were seen in 2004. Until 2004, the meteorological office had confirmed the species appearing almost every year. Similarly, the Choshi Local Meteorological Office in Choshi, Chiba Prefecture, has not recorded sightings of the frog species since 2011. Before, the species had been confirmed in 45 prefectures, with these areas including Hokkaido but excluding Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefecture. In 2016, however, black-spotted pond frogs were only confirmed in Shiga and five other prefectures. From this year, the frog species will be removed from the list of observation targets in Kagawa Prefecture.

“Fireflies have also disappeared in many places. Before, the insect species had been spotted in 44 prefectures, including Hokkaido. But now, fireflies are listed only in 33 prefectures as an observation target. Last year, the species could be confirmed only in 26 of these prefectures, including Kyoto and Fukuoka. Regarding skylarks, their calls have not been heard for four years or longer in Ibaraki, Nagano and Hiroshima prefectures.

“Osamu Mikami, an associate professor of Hokkaido University of Education who is an expert on biology, said the observation results “are important data to monitor global warming. Mikami added: “Rice paddies and farming fields preferred by many species have decreased even in provincial cities where meteorological offices are located, with habitat being rapidly lost. In this situation, it will be difficult for us to fully feel a sense of the seasons.”

Rare Animals on Small Islands in Okinawa

Amami rabbit The Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa Prefecture) and the Satsuna Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture — a chain of 200 islands stretching for 1,000 kilometers between Kyushu and Taiwan — are especially rich in unique plants and animals. The number of plant species per unit area is 45 times greater than the rest of Japan due to the way species can evolve independently — separated from other species — on islands.

There are two large gaps in the Ryukyu Island chain: 1) the northern gap between Yakushima and Amami islands; and 2) a southern gap between the islands of Miyako and Okinawa. The plants and animals in either side of theses gaps tend to be very different form those on the other side. On the northern side of the northren gap, located in the Tokara Strait — and called the Watase Line after early 20th century biologist Shozaburo Watase — the plants and animals are virtually the same as those found in Kyushu and the other main islands of Japan while those south of the gap are markedly different. Similarly the islands south of Okinawa near Taiwan have many animals and plants similar to those in Taiwan because when sea levels dropped during ice ages many were connected to Taiwan and the Asian mainland.

Bonin flying foxes are among the endangered animals in the Ogasawara island. When lemon and agave production was introduced to the islands the bats began eating these and neglecting their role in spreading the seeds of rare plants on the island. Now the bats are considered a pest by farmers and are threatened by feral cats. An effort is being made to round up feral cats and ship them to Honshu.

Zoos,and Tiger Attacks in Japan

In June 2008, a zookeeper was killed by a 150-kilograms Siberian tiger weighing 150 kilograms while cleaning the animal’s cage. The zookeeper lured the tiger from his cage with a chicken and entered the cage to clean it with the tiger entering through a door that the zookeeper failed to firmly close The zookeeper sustained injures to his face, head, neck and hands. The tiger had bloodstains in its mouth. The zoo was closed down after the incident.

In February 2000, Associated Press reported: “A Bengal tiger at an animal rental company mauled a 25-year-old employee to death during feeding time, police said. Masaru Watanabe was left bleeding from the neck for three hours because rescuers were afraid the tiger would leap from the open cage, said police official Koshi Nishino. A zoo official called to the scene in Machida, just outside Tokyo, shot the animal with an anesthetic blowgun. Watanabe was then rushed to a hospital, where he died from loss of blood, Nishino said. [Source: The Associated Press, February 4, 2000]

It took hours for help to arrive from the zoo because the company is in a remote wooded location, police spokesman Tsutomu Tomita said. Police decided against shooting the tiger because they did not want to provoke it, he said. Tomita said the main priority was to make sure the tiger did not harm anyone else, as it was clear from Watanabe's wounds that he had no chance of survival. Watanabe, who had cared for the tiger for two years, was feeding the animal in the cage when it attacked, Nishino said. The seven-employee company, Ikeda Dobutsu Production Co., keeps a tiger, a pony, cats, dogs, and birds for use in television shows, said company official Tsuneki Inoue.

Rare amur leopards have been bred in captivity at the Hiroshima City Asia Zoo. Rare snow leopards have been bred in captivity in Japan. In November 2008, two polar bears sent from a zoo in Sapporo to zoos elsewhere in Hokkaido to impregnate female polar bears were discovered to be females. An elephant has never been born in a Japanese zoo. But this not for a lack of trying. The drought is blamed on the shortage of space and partners. Zoo elephants are rented from Thailand for about $10,000 a year. Because food is so expensive in Japan the cost of feeding an elephant is around $600 a day. The Japanese firm Michi Corporation produce paper made from elephant dung from Sri Lanka and use proceeds made from the paper to help elephants in Sri Lanka.

Animal Pests in Japan

Damage caused to agricultural products by deer, wild boar and other wild animals has been rising year by year, reaching over $250 million in 2009, up $17 million from the year before. One of the biggest problems controlling these animals is that there are not enough hunters to hunt them and the hunters are getting older and older. Few young people are interested in hunting, plus many Japanese find the idea of killing animals abhorrent and don’t like guns.

Reports of crop damage by animals such as raccoons, wild boars, deer, civets and bears is often tied with shortages of wild nuts and other food eaten by the animals in the wild. Netting and fencing have been set up in some parks and reserves to protect rare plants from foraging deer and other animals. In 2008, local governments began obtaining hunting license for some of their employees so they could help cull monkeys, bears, wild boars and other animals that raid crops and cause other problems because not enough hunters could be found.

The number of rats in the cities appears to be on the rise. They have been blamed for starting fires by nibbling through electrical wires and making nests in vending machines. Many of the rats are roof rats which are harder to control than the more common Norway rat.

Pandas in Japan

In the 1972, the Chinese government gifted Japan a pair of giant pandas. In return the Japanese government gave the Chinese two Japanese serow in return. Ueno Zoo’s panda Ling Ling died at the age of 22 in May 2008. The zoo had had pandas since 1972. China said it would loan the zoo a pair of pandas.

Japanese-born panda Rauhin gave birth to two twin cubs at Adventure World in Shirahamacho Wakayama in September 2008. She was the first Japanese-born panda to successfully give birth. Rauhin was born in the same place in September 2000. She was mated with a panda on loan from China. Meimei, a panda at Adventure World in Wakayama, gave birth to 10 cubs in Japan and China. She died in October 2008 at the age of 14.

In August 2010, a panda at Adventure World in Shirahama, Wakayama Prefecture gave birth to twins. It was the second pair of twins for the mother who also gave birth to twins in 2008. In 2012, a baby panda was born in Tokyo's Ueno zoo but it died.

Monkey and Chimpanzee Research in Japan

The pioneers of Japanese macque (snow monkey) studies in Japan were Kinji Imanishi (1902-1992), Junichito Itani (1926-2001) and Masao Kawai (1923- ), ecologists at Kyoto University, who came to Koshima to study wild horses after World War II but began studying the monkeys on Kojima after becoming fascinated by their unusual behavior. Their first major discovery came in 1953 when a Satsue Mirto, a former primary school teacher in Miyazaki, wrote the scientists, describing a 1½-year-old female she saw washing a potato. Japanese researcher can distinguish individual monkeys based on the shape of the eyes and nose, color the face, wrinkles between the eyebrows.

The Kyoto University primate study group discovered an auditory communication system among the monkeys and described the hierarchy of monkey groups, creating the basis for primatology. The theory that the monkeys possessed culture and passed it on from one generation to the next was published in 1954 and stirred up controversy around the world by giving examples in the animal kingdom of behaviors once though to be the exclusively human, blazing a trail for primatologists like Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey

Toshisada Nishida of Kyoto University is one of the world’s leading chimpanzee researchers. The recipient of the 2008 Louis Leakey anthropological award, he has spent much of life studying chimpanzees in Tanzania. Among his discoveries are that low ranking males sometimes play a kingmaking role, deciding who the dominate male will be.

Tetsuro Matsuzawa and the Primate Research Institute

The Primate Research Institute in Inuyama, Japan is one of the world’s most renowned chimpanzee research centers. Its main feature is an outdoor facility that includes a five-story-high climbing tower for the 14 chimpanzees that reside there. Chimps frequently scamper to the top of the tower and take in the view; they tightrope across wires connecting different parts of the tower and chase each other in battle and play. [Source: Jon Cohen, Smithsonian magazine, September 2010]

Tetsuro Matsuzawa, the head of the institute and “ Cognitive Development in Chimpanzees “, works with dozen scientists and graduate students investigating the minds of chimpanzees: probing how they remember, learn numbers, perceive and categorize objects and match voices with faces.Jon Cohen wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “It’s a tricky business that requires intimate relationships with the animals as well as cleverly designed studies to test the range and limitations of the chimpanzees’ cognition.”

Cohen wrote that when he walked out onto a balcony overlooking the institute’s tower with Matsuzawa the chimpanzees spotted them immediately and began to chatter. “Woo-ooo-woo-ooo-WOO-ooo-WOOOOOOO!” Matsuzawa sang out, voicing a chimp call known as a pant-hoot. A half-dozen chimps yelled back. “I am sort of a member of the community,” Matsuzawa said. “When I pant-hoot, they have to reply because Matsuzawa is coming.”

In addition to running the institute for the past four years, Matsuzawa has operated a field station in Bossou, Guinea, since 1986, where he studies wild chimpanzees. “At this field site he has studied everything from the animals’ social dynamics to their feces (to understand the microbes that live in their intestines),” Cohen writes. “He has focused on a capability that many researchers believe highlights a core difference between chimps and us: how they learn to use tools.”

In the primatology world, Matsuzawa is viewed as a top investigator. “Tetsuro Matsuzawa is sui generis, a unique primatologist who studies chimpanzees both in captivity and in the wild, generating rigorous, fascinating and important data about our closest evolutionary cousins,” says evolutionary biologist Ajit Varki of the University of California at San Diego. “Unlike some others in the field, he also has a refreshingly balanced view of human-chimpanzee comparisons. On the one hand he has revealed some remarkable and unexpected similarities between the species — but on the other, he is quick to emphasize where the major differences lie.”

Books: “Cognitive Development in Chimpanzees” by Tetsuro Matsuzawa (Springer, 2006); “The Ape and the Sushi Master: Cultural Reflections of a Primatologist” by Franz de Waal (Basic Books, 2001)

Chimpanzee Research and the Primate Research Institute

Describing the areas of the institute where research is done Jon Cohen wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The lab rooms are about the size of a studio apartment, with humans separated from chimpanzees by Plexiglas walls. Following Japanese tradition, I removed my shoes, put on slippers, and took a seat with Matsuzawa and his team of researchers. The human side of the room was crowded with computer monitors, TVs, video cameras, food dishes and machines that dispense treats to the chimps. The chimp enclosures, which look like oversize soundproof booths from an old TV game show, were empty, but slots cut into the Plexiglas allowed the chimps to access touch-screen computers. [Source: Jon Cohen, Smithsonian magazine, September 2010]

“Matsuzawa’s star research subject is a chimp named Ai, which means “love” in Japanese...One of the researchers pushed a button, gates clanged and Ai entered the enclosure. Her son Ayumu (which means “walk?) went into an enclosure next-door, which was connected to his mother’s room by a partition that could be opened and closed. The institute makes a point of studying mothers and their children together, following the procedures under which researchers conduct developmental experiments with human children.

“Ai sauntered over to a computer screen. The computer randomly splashed numbers 1 through 7 about the screen. When Ai touched the number one, white blocks covered the other numbers. She then had to touch the white blocks in the correct numerical sequence to receive a treat, a small chunk of apple. The odds of correctly guessing the sequence are 1 in 5,040. Ai made many mistakes with seven numbers, but she succeeded almost every time with six numbers, and the odds of that happening by chance are 1 in 720 tries.”

Ayumu’s success rate, like those of other chimps younger than about 10, is better that Ai’s. ...Ayumu next began doing a word-comprehension test known as the color Stroop task. Like his mother, he has learned that certain Japanese characters correspond to different colors. He can touch a colored dot and then touch the word for that color. But does he understand the word’s meaning or has he just learned that when he connects this symbol with that one, he receives a treat? A dog, after all, can be taught to put a paw into a human’s hand and “shake,” but, as far as we know, it has no idea that shaking hands is a human greeting.” Image Sources: Japan-Animals blog except Hokkaido (Nicolas Delerue), panda (WWF), hanko (Goods from Japan) and dinosaurs (Fukui Dinosaur Museum), Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025